God-Awful Guessing and Bad Behavior

I believe that insurance is well positioned to be the glamour industry of the 1990s.

In preceding chapters, we have considered definitions of insurance both in terms of what constitutes an insurance product and in terms of what constitutes an insurance company. To summarize, I have argued that: (1) an insurance product is a financial contract that transfers an aloof or quasi-aloof risk from one party to another; and (2) an insurance company is an enterprise engaged in the business of assuming financial responsibility for such transferred risks in an economically efficient manner by operating subject to marketplace forces.

Of course, insurance companies throughout the world are generally subject to some form of government regulation, and such oversight—in addition to market forces—can have a powerful effect on a company’s internal risk management. In the present chapter, I will provide a brief overview of government regulation of insurance company solvency, and then discuss, in some detail, the most pernicious risks encountered by insurance firms as they build their portfolios of exposures.

Role of Government

The role of government in insurance markets differs greatly from nation to nation and often from one line of business to another within a given nation.1 At one extreme, government may take a laissez-faire approach, relying on market forces to set prices and “thin the herd” of weak insurance companies. At the other extreme is the establishment of a government monopoly as the sole provider of insurance. Government activity may originate at either the national or subnational (i.e., state or provincial) level. In some cases, both national and subnational governments may be involved with regulating or offering insurance coverage in a particular line of business. In the United States, most regulation of insurance is carried out by state governments, whereas important government insurance programs operate at both the federal and the state levels.

Solvency Regulation

The goal of solvency regulation is to protect the financial interests of insurance consumers by enhancing the ability of insurance companies to make good on their obligations to pay claims. This type of regulation is a fundamental activity of insurance regulators throughout the world and is seen as the principal area for government involvement by many nations of Europe and states within the United States.

Governments have a number of tools at their disposal for regulating the solvency of insurance companies:

1. restrictions on licensing, which can be used to require that insurance companies establish a certain minimum level of capitalization before writing business in a given market and which also can be used (or abused) to protect currently licensed companies from competition by limiting the number of companies active in a market;

2. solvency monitoring, which involves the close review of annual financial statements, financial ratios, and risk-based capital methods (to be discussed below), so that financially weak insurance companies are directed to take prompt actions to correct their shortcomings;

3. company rehabilitation, in which regulators take control of the day-to-day operations of an insurance company to save it as a viable corporate entity;

4. company liquidation, in which regulators take control of the assets and liabilities of a unsalvageable insurance company and manage all payments to creditors to make sure that policyholders are treated fairly; and

5. guaranty funds, which use assessments of financially healthy insurance companies to ensure the payment of claims (subject to certain prespecified limits) of policyholders whose insurance companies have gone into liquidation.

In the United States, the ultimate measure of an insurance company’s solvency is its surplus (i.e., net worth, or assets less liabilities), as calculated according to the insurance accounting system known as Statutory Accounting Principles (SAP). All insurance companies are required to file annual financial statements with regulators in their domiciliary state, prepared on a SAP basis, and stock insurers also must file annual financial (10K) statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission on a Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) basis.

Generally speaking, the SAP result in a more conservative (lower) calculation of net worth than do the GAAP because the SAP: (1) require certain expenses to be debited earlier and certain recoveries and tax assets to be credited later; (2) impose restrictions on the discounting of loss reserves as well as on credits for “unauthorized” reinsurance; and (3) exclude certain nonliquid assets, such as furniture and fixtures. These differences arise from the fact that the SAP seek to measure the liquidation value of an insurance company, whereas the GAAP measure the value of the company under a “going-concern” model.

Financial Ratios and Risk-Based Capital

The analysis of various financial ratios—for example, the ratio of written premiums (net of reinsurance) to surplus—has been a major component of solvency monitoring by regulators in many nations for many decades. In the United States, the review of financial ratios was formalized by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in its Early Warning System, created in the early 1970s. In the 1980s, this system evolved into the NAIC’s Insurance Regulatory Information System (IRIS), based upon the calculation of eleven financial ratios for property-liability insurance companies, and twelve financial ratios for life-and-health companies.

With a spate of major insurance company insolvencies in the late 1980s, the IRIS ratios, as well as the entire system of solvency regulation at the state level, came under sharp criticism. The main statistical criticisms of the IRIS ratios were: (1) that the particular ratios used had been chosen subjectively, as opposed to being identified through a formal discriminant analysis of solvent and insolvent insurance companies; and (2) that the “normal” ranges for the individual ratios also were chosen subjectively, rather than through a formal statistical procedure.

In the early 1990s, in response to criticisms of IRIS, the NAIC implemented the more sophisticated Risk-Based Capital (RBC) system as its primary statistical tool for solvency monitoring. The RBC analysis (modeled after a similar approach applied by the Securities and Exchange Commission to commercial banks) identifies various categories of risk for insurance companies, and then computes a minimum surplus requirement associated with each category as the product of a specified annual statement item and a subjective factor. The insurance company’s overall minimum surplus—called the authorized control level RBC—is then calculated as the sum of the individual surplus requirements for the various risk categories, with adjustments for correlations among the different risks.2

Under the RBC approach, regulators may require an insurance company to perform financial self-assessments and/or develop corrective-action plans if its surplus falls below 200 percent of its authorized control level RBC. Furthermore, regulators are authorized to take direct action (e.g., company rehabilitation) if the insurance company’s surplus falls below this minimum RBC and are required to take action if the insurance company’s surplus falls below 70 percent of the minimum level. Outside the regulatory arena, the RBC methodology often is used by insurance companies, insurance rating agencies, and policyholders as part of any comprehensive evaluation of company solvency.

An Insurance Paradox

Throughout the risk-and-insurance literature, the premium-to-surplus (P/S) ratio—that is, the ratio of an insurance company’s annual net premiums to its average surplus (net worth)—is viewed as a fundamental measure of financial leverage.3 Consequently, one would expect this ratio to provide some evidence of the benefits of the law of large numbers (LLN). In particular, one might anticipate that the P/S ratio tends to increase as a function of premiums, since insurance companies with more premiums—and hence a larger number of policyholders—should enjoy greater financial stability through diversification and thus be able to operate at a higher leverage.4 However, a simple analysis of real-world data belies this intuition.

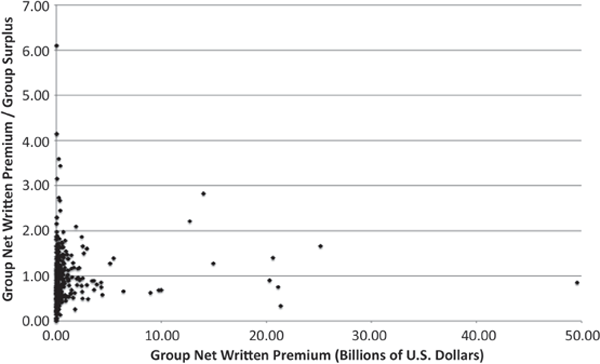

Premium-to-Surplus Ratio vs. Premium (U.S. P-L Insurance Groups, Calendar Year 2009) Source: A. M. Best Company (2010).

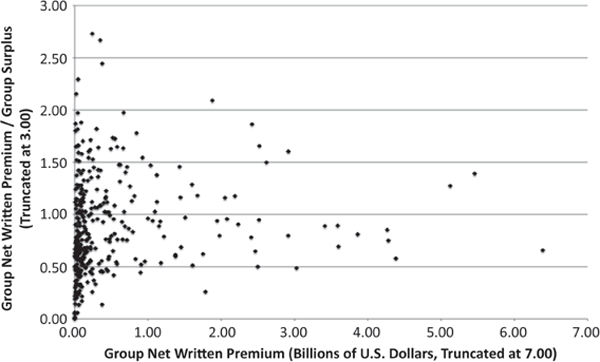

The scatter plot in Figure 8.1 presents the P/S ratio vs. premiums for all U.S. property-liability insurance groups doing business in calendar year 2009.5,6 Although a cursory inspection of these data might suggest an inverse power relationship, this type of model would give too much credence to a few outliers—namely, the points from the highly unusual groups with rather small premium volumes and large P/S ratios. To get a better idea of the true relationship between the P/S ratio and premiums, one can truncate the data by removing all groups whose P/S ratio is greater than 3 and whose annual premiums are greater than $7 billion. Although the latter set—that is, those groups with a premium volume greater than $7 billion—clearly constitute many of the most successful and stable insurance groups in the U.S. market, their removal helps to clarify what is going on within the cluster of smaller groups at the left of the plot and does not alter any conclusions.

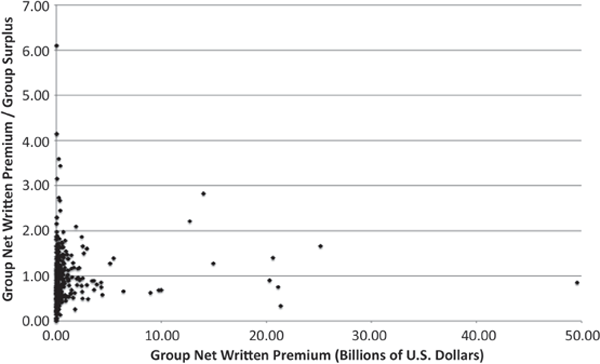

From Figure 8.2, it can be seen that the relationship between the P/S ratio and premiums is essentially a constant function, with slightly positively skewed random fluctuations above and below an overall average of about 1. In other words, a group’s premium volume has no systematic impact on the magnitude of its overall leverage, and the only discernible effect of premium volume is on the variation of the P/S ratio: as groups write more business, there is less statistical dispersion among their leverage ratios. This last effect is unsurprising; after all, one would expect smaller groups to be either: (1) less-established enterprises that are naturally somewhat removed from market equilibrium; or (2) niche players that intentionally deviate from market norms. However, the complete absence of any increase in the P/S ratio is surprisingly counterintuitive.

Premium-to-Surplus Ratio vs. Premium (Truncated Data, U.S. P-L Insurance Groups, Calendar Year 2009) Source: A. M. Best Company (2010).

So how can this paradox be resolved?

Effects of Increasing Writings

To seek an answer, one must look for the presence of other, less benign effects arising from an increase in an insurance company’s number of policyholders. A quick list of phenomena associated with increased writings would include the following positive and negative effects:

Positive Effects

• Law of large numbers. As more policyholders join the insurance company’s risk pool, the variability of the average loss amount tends to shrink, enhancing the stability of the company’s financial results through diversification.

• Reduced actuarial pricing error. As more historical data are collected, the insurance company’s actuaries are able to make better forecasts of the premiums necessary to offset losses and expenses.7

• Reduced classification error. As more policies are written, the insurance company’s underwriters gain greater experience in evaluating the risk characteristics of policyholders and make fewer mistakes assigning them to their proper risk classifications.

• Reduced information deficiencies. As more policies are written, the problem of asymmetric information from self-selecting policyholders with private information about their own loss propensities is diluted.

• Capital accretion. As profit loadings are collected from more policyholders, the insurance company’s surplus increases, providing a greater financial buffer against insolvency.

Negative Effects

• Increased classification error. As more policies are written, the insurance company’s underwriters begin to encounter less-familiar types of policyholders (from new demographic backgrounds and/or new lines of business) and have trouble assigning them to the proper risk classifications.

• Increased information deficiencies. As more policies are written, the insurance company’s underwriters begin to encounter less-familiar types of policyholders, and the problem of unobservable—not asymmetric—information becomes more significant.

• Decline in impact of initial net worth. As more policyholders join the insurance company’s risk pool, the impact of the financial buffer provided by the company’s initial surplus, on a per-exposure basis, diminishes.

Naturally, it is not the number of negative effects that is determinative, but rather their relative significance. As any experienced insurance regulator knows, the first two items on the negative list frequently lead to insolvency when an insurance company attempts to expand its book of business too rapidly through new types or new lines of exposures that it cannot underwrite effectively.

For a classic example, one need look no further than the insurance group mentioned at the beginning of this chapter. In 2001, Saul Steinberg’s Reliance Group Holdings (RGH) filed for bankruptcy, barely making it through the decade Steinberg had foreseen as “glamorous” for insurance. Having taken control of RGH through a leveraged buyout in 1968, Steinberg gained notoriety as a corporate raider in the 1980s with attempts to take over Disney, Quaker Oats, and other companies. Ultimately, however, it was not these forays into high finance that killed RGH, but rather the careless underwriting of its largest insurance subsidiary, the Reliance Insurance Company. Sadly, this nearly 200-year-old Pennsylvania insurance company succumbed to the massive unfunded liabilities generated by its indiscriminate writing of a novel type of workers compensation “carve-out” reinsurance.

What is particularly interesting is that the data from Figures 8.1 and 8.2 strongly suggest that many insurance companies—not just those unfortunate enough to end up insolvent—engage in these same activities. This behavior may well be described as a sort of Peter Principle for insurance markets.8 In other words, insurance companies frequently convert the benefits of the LLN (and other positive effects of writing increased numbers of policyholders) into economic subsidies for expanded writings, investing in less-familiar categories of business until their P/S ratios approach the market average.

Why this apparent inefficiency exists is an interesting question and one that has not been investigated sufficiently by insurance researchers. One obvious possibility is that insurance companies derive economic benefits from increased market share that offset the disadvantages of less- effective underwriting. Whatever its origin, such an industry practice is unlikely to be challenged by those who monitor the distribution of P/S ratios most closely: government regulators. Although clearly concerned with all threats to insurance company solvency, regulators invariably find it politically difficult, if not impossible, to impede voluntary company efforts to expand the availability of insurance products for consumers.

The Real Risks of Insurance

As noted above, a common way for insurance companies to get into financial trouble is by expanding their portfolios so rapidly that underwriting procedures are overwhelmed by classification errors and information deficiencies. In a very real sense, therefore, it can be argued that it is these underwriting uncertainties, and not the more commonly discussed risks of actual losses and actuarial forecasts, that are most important to the insurance enterprise.

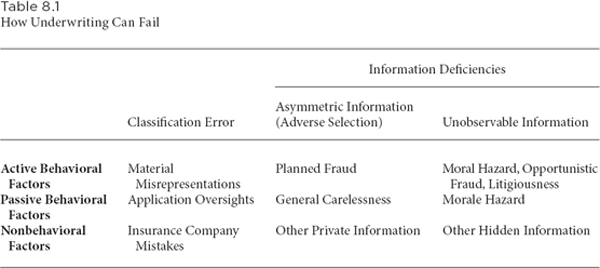

Table 8.1 provides a brief summary of how underwriting failures can occur, with the information problems divided into two subcategories (asymmetric information and unobservable information, respectively) and each type of underwriting issue broken down according to three possible causes (active behavioral factors, passive behavioral factors, and nonbehavioral factors).

A classification error occurs whenever an insurance company mistakenly identifies a particular policyholder as belonging to one risk classification when the policyholder actually belongs to a different one. Naturally, this is more of a problem for the insurance company when it assigns the policyholder to a lower-risk classification than is deserved, resulting in an inadequate premium. In most cases, such errors are attributable to honest human mistakes made either by the policyholder in completing a policy application or by the insurance company in evaluating the application. Sometimes, however, policyholders intentionally withhold or falsify required information in completing their applications. For example, a life insurance applicant might claim to be a nonsmoker, when in fact he or she is a heavy smoker. Such material misrepresentations form a type of insurance fraud that is usually treated as a civil contract violation (rather than a criminal act) and can result in the abrogation of the insurance company’s responsibilities under the policy.

How Underwriting Can Fail

Information deficiencies refer to a larger and more complex class of problems, many of which are extremely difficult to prevent or manage. Essentially, they occur when a policyholder poses a significantly higher risk than that associated with the classification to which the policyholder is (correctly) assigned. In other words, although the policyholder’s overt characteristics indicate a specific classification, the policyholder possesses other, difficult-to-observe characteristics that make the policyholder’s risk to the insurance company greater than what is expected.

The problem of asymmetric information arises whenever a policyholder possesses some private information about the policyholder’s own propensity to generate losses of which the insurance company is unaware. This phenomenon is also frequently called adverse selection (although the plain meaning of this term could be applied equally well to the problem of unobservable information as an insurance company increases its book of business). Asymmetric information most commonly involves nonbehavioral factors—as when a life insurance applicant knows that a close family member has just been diagnosed with a life-threatening genetic illness—or passive behavioral factors—as when an automobile insurance applicant knows that he or she often uses a cell phone while driving. Cases of planned fraud—such as insuring an expensive piece of jewelry and then pretending that it has been stolen—are rarer and generally can be prosecuted as criminal felonies.

Unobservable information simply means that neither the insurance company nor the policyholder knows some critical information about the policyholder’s propensity to generate losses. As with asymmetric information, it most commonly involves nonbehavioral factors—as when a life insurance applicant has an undiagnosed malignant tumor—or passive behavioral factors. However, in the case of unobservable information, any behavioral factor, whether passive or active, has the special property that it is triggered by the purchase of insurance (rather than being present prior to the insurance purchase). For this reason, insurance specialists use the terms morale hazard and moral hazard to describe the passive and active factors, respectively.

Morale hazard denotes an increase in the policyholder’s carelessness with regard to the covered peril that is prompted by the purchase of insurance. For example, after purchasing a homeowners insurance policy that provides coverage for stolen contents, an individual may be less attentive to locking his or her door when leaving the house. Moral hazard, on the other hand, denotes a type of insurance fraud that is planned after the purchase of insurance but before the occurrence of a loss event. A classic example is that of a homeowner who wants to sell his or her house, but finds that the current market price is below the value for which the house is insured, so he or she proceeds to ignite an “insurance fire.”

It is interesting to note that most professional economists see little meaningful distinction between morale hazard and moral hazard and tend to use the latter term to describe both phenomena. Clearly, this is a good example of the power of abstraction, although not necessarily an example of a good use of such power. By failing to distinguish between these two terms, one essentially equates a negligent act with a premeditated crime.

In addition to moral hazard, there are two other active behavioral factors that fall under the category of unobservable information. Unlike moral hazard, which involves an action taken after the purchase of insurance but before a loss event, the other two factors—opportunistic fraud and litigiousness— both arise after a loss event occurs.

Opportunistic fraud describes a decision by the policyholder to “pad the bill” for his or her insured losses. For example, after a burglary, the policyholder might report certain expensive items stolen that never were owned in the first place. Like planned fraud and instances of moral hazard, opportunistic fraud generally may be prosecuted as a felony, but often is more difficult to prove.

Litigiousness refers to the filing of unjustified third-party claims and easily can raise costs for the policyholder’s own insurance company, as well as the insurance company of the party being sued. For example, after an automobile collision, one driver (the “victim”) might try to build a case for pain and suffering compensation as a result of dubious soft-tissue injuries caused by another driver. To build his or her case for such compensation, the victim first must seek extensive medical treatments to demonstrate the seriousness of the injury. Since finding a friendly doctor or chiropractor is rarely a problem, there is little that can be done to stop this type of behavior, short of enacting no-fault insurance laws. It is indeed very instructive that one often hears the almost whimsical term frivolous lawsuit used to describe what is in fact highly destructive tort fraud.

A Tree Falls

Some years ago, a “friend of mine” moved to the greater Philadelphia metropolitan area. Owning two automobiles, he quickly decided that, given the high price of automobile insurance in southeastern Pennsylvania,9 and the lack of sufficient off-street parking at his new house, he would reduce his personal fleet to just one car. In short, he would keep the newer car and dispose of the older one.

There was one problem with this plan, however. Quite simply, my friend was too lazy to go through the hassle of selling his older vehicle. Starting with the best of intentions, as time went on he found himself hesitating and delaying and postponing and demurring and procrastinating, all the while paying the extra insurance premiums for a second vehicle that he rarely drove.

One day my friend’s attention was drawn abruptly to a different insurance problem: He experienced a psychological premonition that the large maple tree standing by the sidewalk in front of his house would break apart during a storm, posing a danger to passers-by. The source of this inkling is hard to pin down, but it may have arisen from one or more of the following: a barely hidden animosity toward the tree for producing so many leaves during the previous fall; a strange paranormal experience involving a tree that occurred earlier in his life; the recent death of a young child in a neighboring town who was killed by a falling tree branch; and the presence of numerous attorneys on his street.

So now, in addition to trying to get rid of his car, my dilatory friend had to decide what to do with his dangerous tree. To complicate matters, he rented his house, so the tree technically did not belong to him. However, knowing something about the world of insurance and litigation, my friend was well aware that his lack of ownership would not protect him in the case of a serious injury. Although a falling tree branch is about as close to an act of God as one can find, an injured victim in today’s America generally is not satisfied complaining to God. Rather, he or she is likely to want to file a legal claim against anyone with a potential connection to the tree’s downfall—which, in a civil justice system where scientific causality is often irrelevant, would mean the owner of the property, the tenant, and perhaps even a neighbor whose dog was observed urinating on the tree trunk shortly before the incident.

In any event, it was not long before my friend decided that the wisest course of action was to contact his landlady and report his concern about the tree to her. By informing her properly, he hoped to construct a possible legal defense in the case of an accident—that is, that he had done all he could be expected to do as a tenant about the hazard. Of course, my friend’s character had not changed much, so, having reached a firm decision, he promptly procrastinated regarding its implementation. Nevertheless, after a few weeks of prodding from his wife and a few nights of fitful sleep, he finally called the tree’s owner.

Suffice it to say that the landlady dealt with the matter rather expeditiously. Neither excessively anxious nor unduly insouciant, she quickly made arrangements for a professional tree surgeon to evaluate the tree’s health. When the expert suggested that all that was needed was a light trimming, she was content to accept this advice and proceeded with the recommended work.

Fortunately, the landlady’s action provided some assurance to my friend. Although it in no way dispelled his premonition, it did seem to comfort him that there were now two additional parties—the landlady and the tree surgeon—who stood ahead of him in line to be sued. It was thus with a certain measure of relief that he returned to the problem of having one car too many.

By now, the insightful reader will have noted that a new option had presented itself. Instead of selling his unwanted car, my friend simply could park it under the aforementioned maple tree and wait for the inevitable falling branch to destroy it. Just because the landlady and her tree surgeon did not believe the tree posed any real danger, this had not altered my friend’s confidence in the impending disaster one bit. So, being the procrastinator he was, he decided to undertake this most passive and optimistic of options—and simply waited.

Interestingly, he had to wait less than a year (which is nothing for an experienced procrastinator), until an early spring ice storm indeed knocked a large branch from the tree, crushing the front end of the unwanted car. No longer wasting any time, my friend immediately called his insurance company and was very pleased to hear from the accommodating claim adjustor that the car truly was “totaled.”

Thinking about this strange sequence of events, I find myself having a difficult time fitting it into the categories afforded by Table 8.1. Certainly this was not an issue of classification error, and certainly it was not a problem of adverse selection (since my friend possessed no private information prior to purchasing his automobile insurance policy). That leaves only the rightmost column of the above table. Also, it seems fairly clear that my friend did manifest rather unusual behavior—parking his car under the maple tree—that ultimately resulted in the car’s demise. That leaves two possibilities: moral hazard (i.e., planned fraud encouraged by the purchase of insurance) and morale hazard (i.e., carelessness encouraged by having insurance coverage).

At this point, I am tempted to conclude that my friend’s action was an instance of moral hazard; after all, he did park the car under the tree deliberately, not just as a matter of carelessness. But is it reasonable to believe that his desire for the tree to fall is equivalent to the commission of fraud? From the facts of the story, it appears that there was no meaningful evidence that the tree was likely to fall. So can my friend be guilty of a crime just by wishing it to happen?

ACT 2, SCENE 3

[A different insurance company office. Claimant sits across from claim adjustor at adjustor’s desk.]

ADJUSTOR: Mr. Powers, who is this friend that you discuss in Chapter 8 of your book? You know, the one whose car was crushed by a tree?

CLAIMANT: He’s someone very close to me. Someone I know well, both professionally and personally. But his particular identity isn’t that important. He’s supposed to be an Everyman type of character, like Adam and Eve in the earlier tree-related dialogue.

ADJUSTOR: I see. That’s very interesting, but somewhat off point. Having read your book, I notice that you take great care with your use of punctuation: periods, commas, quotation marks,…, ellipses, etc.

CLAIMANT: Thank you. It’s kind of you to say so.

ADJUSTOR: Yes. Then perhaps you could explain why you first introduce your close friend—the one you know both professionally and person- ally—as a “friend of mine,” in quotation marks?

CLAIMANT: Hmm …

ADJUSTOR: And while you’re thinking about that, I also would note that you mention your friend had “a strange paranormal experience involving a tree that occurred earlier in his life.” Is that correct?

CLAIMANT: Yes … it is.

ADJUSTOR: Then, in Chapter 15, you go into some detail describing a strange paranormal experience involving a tree that you yourself had earlier in life. Is that true?

CLAIMANT: Yes … it is.

ADJUSTOR: Mr. Powers, let’s stop beating around the bush. This “friend” of yours is none other than you, yourself, isn’t it?

CLAIMANT: OK, OK. You’ve unmasked me; I admit it.

ADJUSTOR: So then, you also admit to committing willful insurance fraud by parking your car under the maple tree in your front yard?

CLAIMANT: No! Never! Fraud would require moral hazard, and I won’t even acknowledge morale hazard.

ADJUSTOR: But you do confess that you parked your car under the tree?

CLAIMANT: Yes.

ADJUSTOR: And that you fully anticipated a large tree branch would fall on the car?

CLAIMANT: Yes.

ADJUSTOR: Well, then, how is that any different from intentionally parking your car in the middle of a junkyard where you know that a car compactor will pick it up and crush it?

CLAIMANT: It’s completely different. In the case of the car compactor, everyone would agree that the car would be destroyed. In the case of the falling branch, even tree experts asserted that the car was perfectly safe.

ADJUSTOR: Tree experts, perhaps; but not you?

CLAIMANT: That’s correct.

ADJUSTOR: Well, then, how would you describe your premeditated use of the tree?

CLAIMANT: That’s easy. I’d say it was an example of a hedge.

ADJUSTOR: A hedge? But we’re talking about a tree here.

CLAIMANT: I mean a financial hedge. You see, I believed that the tree branch would fall and that therefore I, as the resident tenant of the property, would be subject to a small probability of being found liable for someone’s injury. So I essentially hedged—or offset—the chance of liability with the correlated chance of resolving my car problem. In other words, if the tree broke, then I would be exposed to a liability loss, but at the same time to the gain of getting rid of my car.

ADJUSTOR: Mr. Powers, I believe you’re psychotic!

CLAIMANT: I’d prefer the term psychic. But let’s wait until Chapter 15.