The Role of Risk Classification

Even the Wicked prosper for a while, and it is not out of place for even them to insure.

Although not as universal as solvency regulation, rate (or price) regulation is used extensively by many nations of the world and often relied on for market stability by developing countries. In the United States, the purpose of rate regulation is twofold: (1) to protect insurance consumers from excessive premiums or unfairly discriminatory premiums (i.e., premium differences that cannot be justified by differences in risk characteristics among policyholders); and (2) to protect insurance companies (and therefore insurance consumers) from inadequate premiums that may threaten company solvency.

In the present chapter, I will offer a brief summary of the objectives and methods of rate regulation, and then probe one of the most controversial aspects of insurance: the risk classification used in underwriting and rating.

Rate Regulation

In the United States, most state governments regulate at least some insurance premiums, although the level of regulatory activity generally varies greatly from line to line.2 Five categories are often used to describe the various types of rate regulation:

• fix and establish, under which the regulator sets insurance premium levels, with input from insurance companies and other interested parties;

• prior approval, under which insurance companies must secure regulatory approval before making any adjustments in premiums;

• file and use, under which insurance companies must notify regulators of premium adjustments a specified period of time before implementing them in the market;

• use and file, under which insurance companies must notify regulators of premium adjustments within a specified period of time after they have been implemented; and

• open competition, under which insurance companies can make premium adjustments without seeking authorization from or providing notification to regulators.

Under all of the above systems, regulators generally have the right to challenge—through an administrative or court hearing—premiums that are in violation of applicable rate regulatory and consumer protection statutes.

In some property-liability insurance markets around the world, rates are established through a bureau or tariff rating system, under which an industry or quasi-governmental agency collects statistical data from many or all insurance companies and computes manual rates that are then approved by the insurance regulator. Under a system of bureau rating, an individual insurance company often is permitted to deviate by a constant percentage from the manual rates based upon the company’s historical losses and/or expenses. Price competition also may take place through dividends awarded by insurance companies to individual policyholders.

Another tool of government for addressing issues of insurance pricing, as well as insurance availability, is the establishment of residual markets. These “insurers of last resort” are generally industry-operated entities, commonly taking either of two basic forms: (1) an assigned risk plan, through which hard-to-place policyholders are allocated randomly among the insurance companies writing in a given market; or (2) a joint underwriting association or insurance facility, through which hard-to-place policyholders are provided insurance by a pooling mechanism that requires all insurance companies in the market to share the policyholders’ total risk. In some cases, residual markets may be handled through government insurance programs.

Risk Classification

For most insurance companies, risk classification arises in two principal contexts: underwriting and rating.3 Underwriting refers to the process by which an insurance company uses the risk characteristics of a potential policyholder to decide whether or not to offer that individual or firm an insurance contract. Rating is the process by which an insurance company uses a policyholder’s risk characteristics to calculate a particular premium level once a contract has been offered. Naturally, in a well-organized insurance company the two facets of risk classification work hand-in-hand so that the company will not agree to a contract for a policyholder whose characteristics fall outside the firm’s rating scheme and the company will not refuse a contract for a policyholder whose characteristics are comparable with previously rated policyholders.

The economic motivation for risk classification is quite simple: without it (or some effective substitute) voluntary markets will fail to cover all potential policyholders who desire insurance.4 This can be seen by considering a hypothetical market for individual health insurance in which there are two types of potential policyholders: generally healthy people (GHs), who use $2,000 worth of medical services on average per year and compose 80 percent of individuals, and chronically ill people (CIs), who use an average of $32,000 worth of services annually and account for the remaining 20 percent. Assume further that no deductibles, limits, or copayments apply to the reimbursement of medical claims and that insurance companies require a premium loading of 25 percent of expected losses to cover profits and various expenses.5 Then, given that underwriting and rating are employed, GHs will pay an annual premium of $2,500, whereas CIs will pay a premium of $40,000. However, if risk classification is not used, and insurance companies offer contracts to all policyholders at one fixed price, then: (1) the insurance companies will have to charge a premium of at least $12,000 to break even (based upon a four-to-one ratio of GHs to CIs); and (2) many of the less risk-averse GHs will balk at such a high premium, not purchase insurance, and begin an adverse-selection “spiral” that leaves the insurance companies with only the CIs and a few very risk-averse GHs who are willing to pay a premium of about $40,000.

One way to prevent the adverse-selection spiral and ensure that all policyholders get covered for the same $12,000 premium is for government to make the purchase of health insurance mandatory, rather than voluntary. This is essentially what the new U.S. health care law (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010) proposes to do.6 However, two important criticisms of this approach are immediately apparent. First, one might argue that by charging the CIs substantially less than their actuarially fair premium of $40,000, the government is encouraging morale hazard by removing an important incentive for less-healthy policyholders to engage in appropriate risk control behavior, such as reducing alcohol intake, improving diet, and exercising. Second, one could argue that, as a simple matter of social justice, the government should not force the GHs to be charged a premium that is so disproportionate to their underlying expected medical costs.

The first criticism—that of encouraging morale hazard—is clearly based upon more positive economic considerations than is the second, rather normative criticism. However, although it is readily apparent that risk control efforts can be very effective in many insurance lines, I would argue that individual health insurance is not one of them. This is because classification-based risk control incentives are effective only when either: (1) policyholders are commercial enterprises capable of long-term self-disciplinary measures and able to justify substantial premium reductions through their own historical costs; or (2) policyholders are able to obtain substantial premium reductions by making verifiable behavioral changes that result in lower costs—and individual health insurance fails to satisfy either of these conditions.

To make this point more compelling, consider a simple thought experiment: Imagine an individual policyholder with heart disease who chooses to eat more healthful foods primarily for the purpose of lowering his or her insurance premium rather than primarily for the purpose of avoiding surgery and living longer. Unlike an individual who ceases smoking and thus may qualify for a classification-based behavior-change discount (i.e., nonsmoker versus smoker), a heart patient who embraces an improved diet will benefit from decreased premiums only if he or she is joined in the effort by many other policyholders with heart disease (over whose diets the initial policyholder has no control) and after the passage of many years (that is, after the medical costs of all policyholders with heart disease can be shown to have decreased in the insurance company’s database). Consequently, such an individual would have to be inhumanly optimistic and patient to make such a dietary change.

The second criticism—that of social injustice—raises some interesting issues. Superficially, the argument seems undeniably sound. After all, government does not require the owners of inexpensive automobiles to subsidize the owners of luxury cars; therefore, by analogy, why should government require those requiring less-expensive health insurance (i.e., GHs) to subsidize those requiring more-expensive policies (i.e., CIs)? One answer, of course, is that, unlike the owners of luxury cars, the CIs do not make an active decision to choose the more expensive product and thus should be afforded a certain degree of sympathy. Nevertheless, compassion alone does not provide an adequate basis for sound public policy.

The real problem with risk classification is that any attempted normative justification is meaningless at the level of individual policyholders. Since the particular individuals responsible for using medical services during a given policy period are not known with certainty in advance, it follows that a CI policyholder who pays $40,000 (under a voluntary policy) but does not use any medical services is substantially more aggrieved than a GH policyholder who pays $12,000 (under a mandatory policy) and generates no medical costs. The fact that there are fewer of the former than the latter is entirely irrelevant at the individual level. Hence, normative social justice considerations actually argue against, rather than in support of, risk classification systems.

To see this another way, consider a second thought experiment: Imagine a future time in which insurance companies can use a simple blood test to determine, in advance, exactly how many dollars in medical costs each individual policyholder will generate during the coming year. Under such an improved system, risk classification-based insurance obviously could not exist because each policyholder would occupy a unique risk classification and simply pay a premium equal to his or her medical costs plus an unnecessary 25 percent loading. Thus, the only reason risk classification-based insurance can exist today is that the classifications used are sufficiently coarse that there is still the possibility of some policyholders (e.g., the CIs and GHs who do not use any medical services) subsidizing others. In effect, by imposing the particular GH/CI breakdown, we are forcing certain CIs to provide huge subsidies (of up to $40,000), whereas under a system of uniform premiums, we would be forcing certain CIs and GHs to provide much smaller subsidies (of at most $12,000). Selecting the former alternative over the latter—given that mandatory coverage removes adverse-selection concerns and risk control considerations are not applicable—is therefore not only arbitrary, but also disproportionately punitive.

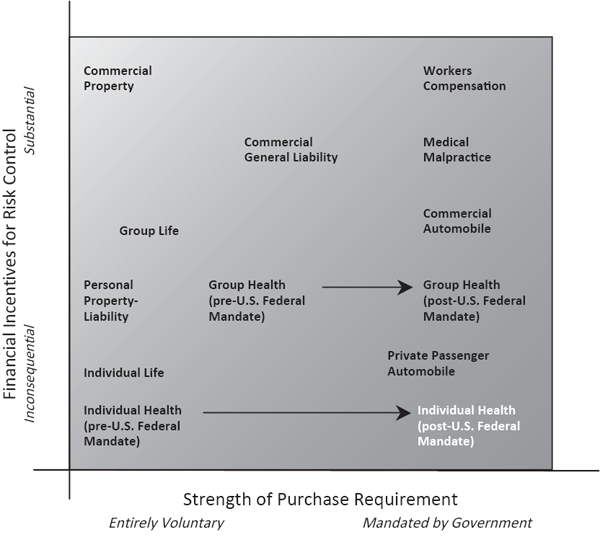

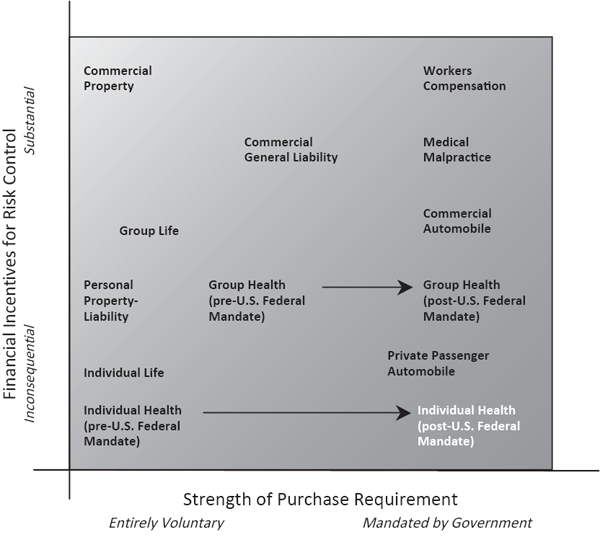

Usefulness of Risk Classification (Darker means less useful).

In summary, one can draw the following conclusions:

• In voluntary insurance markets, risk classification is generally necessary in order to succeed in covering most potential policyholders.

• In mandatory insurance markets, risk classification is not necessary in order to cover all potential policyholders, but it may discourage morale hazard by providing effective financial incentives to control risks in some cases (e.g., in commercial lines that permit policyholders to enjoy substantial premium reductions from their own improved loss experience and in any lines that permit policyholders to enjoy substantial premium reductions from verifiable behavioral changes).

• At the level of individual policyholders, normative social justice arguments oppose, rather than support, the use of risk classification systems.

The significance of the first and second bullet points is illustrated in Figure 9.1, which provides a simple paradigm for determining when risk classification is more or less useful.7 In the upper left (unshaded) corner, insurance is voluntary and risk classification systems offer policyholders the possibility of obtaining substantial premium reductions through risk control efforts. In the lower right (shaded) corner, insurance is mandatory and risk classification systems afford little or no meaningful premium reductions through risk control.

Not to forget the third bullet point, I would observe that risk classification is more than simply “less useful” in the lower right corner; rather, it is particularly unjust to those lower-cost individuals who happen to be placed in more expensive classifications. Such policyholders not only are required by law to purchase insurance, but also are compelled to accept premiums based upon classifications that they cannot change through risk control efforts. For this reason, it is quite sensible for the new U.S. health care law to eliminate certain risk classifications in individual health insurance. This is also why risk classification schemes in private passenger automobile insurance (the “nearest neighbor” of individual health insurance in Figure 9.1) should always be subject to close scrutiny in jurisdictions where this coverage is required by law.

Controversies

In addition to the general issues discussed in the previous section, insurance regulators in the United States often must address specific problems of wide disparities in personal insurance premiums among different sociodemographic classes.8 Whereas insurance industry actuaries generally consider rating systems to be fair if differences in pure premiums (i.e., premiums net of profit and expenses) reflect substantive differences in expected losses, regulators (and the public at large) may not find a correlation with expected losses sufficient justification for using certain sociodemographic variables in underwriting and/or rating. Issues of causality, controllability, and social acceptability often prevent policymakers from accepting the use of a proposed risk classification in a given line of personal insurance.

There are several fundamental reasons for skepticism regarding sociodemographic risk classification variables in personal insurance. These include:

1. Doubts about actual correlation with risk. For example, are younger drivers really more likely to have automobile collisions than older drivers? After all, one often hears about aged drivers with poor eyesight and/or slow reflexes causing collisions. If that is so, then why do senior citizen discounts exist?

2. Doubts about actual causation of risk. Granting that younger drivers actually are more likely to have collisions than older drivers, is age a true causal factor? Another obvious possibility is that driving experience provides the fundamental causal link. Should driving experience be used instead of age to avoid treating younger, but more experienced drivers unfairly?

3. Doubts about complete causation of risk. Assuming that age is a true causal factor because younger people are intrinsically less careful (and therefore more likely to drive fast, drive while intoxicated, etc.), should this factor be applied to everyone equally? For example, there may be younger drivers who are teetotalers and therefore never drive while intoxicated. Is it fair to use age as a factor, but not alcohol consumption?

4. Doubts about individual fairness. Assuming that age is a true causal factor that applies to everyone equally (i.e., without need for modification for such things as alcohol consumption), is it fair to penalize younger people for their age? After all, a younger person cannot take any action to reduce expected losses by changing his or her age, so the risk classification system simply imposes penalties for high expected losses, rather than providing financial incentives for reducing losses.

5. Doubts about group fairness. Finally, even if it is accepted that age is a true causal factor that applies to everyone equally and that it is reasonable to make younger people—as individuals—pay for their intrinsic carelessness (with no hope of reducing losses), does society really want to penalize younger people as a sociodemographic group? After all, younger people tend to be less affluent on the whole. Why not simply remove age as an underwriting and/or rating classification and thereby spread the losses over everyone?

When implementing a new risk classification, insurance companies must obtain the explicit or implicit approval of insurance regulators in regulated markets and at least the tacit agreement of consumers in competitive markets. As a result of concerns one through three above, companies may be expected to demonstrate not only an empirical correlation between the proposed risk classification and expected losses, but also a causal connection that is effective in predicting losses. Moreover, even when issues of correlation and causality have been successfully addressed, companies may encounter difficulties arising from concerns four and five when a risk classification is based upon a characteristic that is not within a policyholder’s control. (For example, the make and model year of an automobile generally are not controversial factors in automobile insurance, whereas the gender and age of the driver may be.)

Premium Equivalence Vs. Solidarity

As mentioned above, it usually is desirable in voluntary insurance markets to employ one or more risk classifications for both underwriting and rating purposes. However, any insurance company establishing a risk classification system must confront a fundamental trade-off between the economic costs and the economic benefits associated with the system’s degree of refinement. On the one hand, the use of smaller, more homogeneous classifications enables the company to price its product more accurately for specific subsets of policyholders, thereby reducing problems of adverse selection (in which lower-risk policyholders decline to purchase insurance because they perceive it to be overpriced for their levels of expected losses) and providing financial incentives for risk control (by lowering premiums for policyholders taking specific steps to reduce the frequency and/or severity of losses). On the other hand, the use of larger classes tends to make insurance more affordable for a greater number of individual policyholders (because premiums for higher-risk policyholders remain substantially lower than what is indicated by their actual losses). These two conflicting effects are captured, respectively, by the principles of premium equivalence and solidarity.

The principle of premium equivalence asserts that an insurance company’s book of business should be partitioned into classifications that are homogeneous with respect to risk and that the total premiums collected from each group should be based upon the total expected losses for that group. Although this principle certainly makes intuitive sense, it actually describes an ideal that is impossible to implement in practice. This is because each individual policyholder possesses a unique constellation of risk characteristics, so any group of more than one policyholder must be some what heterogeneous. Instead, the best that insurance companies can do is to create a system of risk classifications in which the policyholders in each cell have similar risk profiles. In short, prospective policyholders representing approximately equivalent exposures are underwritten and rated in the same way.

Alternatively, the principle of solidarity asserts that individual policyholders should not be obligated to pay their specific losses, but rather that all policyholders should contribute equally to the payment of total losses. In a sense, this concept forms the basis for insurance; in other words, the “lucky” policyholders (i.e., those that do not experience a loss) subsidize the “unlucky” ones. In the case of complete solidarity, the insurance company represents the total pool of policyholders and assumes the risk of total losses.

To understand this issue more clearly, let us return to the example provided in item three above, in which it was assumed that age is a true causal factor of greater automobile insurance losses because younger people are intrinsically less careful (and therefore more likely to drive fast, drive while intoxicated, etc.). In that context, suppose that a young male policyholder realizes from anecdotal observations that a large number of automobile collisions among his peers are caused by individuals driving to or from parties where alcohol is served. Armed with this information, the young policyholder petitions his insurance company for a premium discount based upon the fact that he never attends such parties. However, the policyholder soon finds that his request is fruitless because the insurance company possesses no data to support his argument. When asked whether it has any plans to collect such data, the company responds that even if such data were available, it could not be used to create a risk classification for nonpartiers because anyone could declare membership in that category, and the company would not have the resources to audit such assertions.

In short, although the young policyholder would be better off with either a coarser risk classification scheme that ignored age or a more refined risk classification scheme that recognized both age and party attendance, he is stuck with the somewhat arbitrary status quo selected by insurance companies and regulators. For him, age is a controversial risk classification; for other policyholders in private passenger automobile and other personal insurance lines, different classifications might be controversial.

Causes of Controversy

Although all sociodemographic variables are subject to a certain degree of regulatory scrutiny, some—such as race/ethnicity and income—are more provocative than others. To explore the hierarchy of controversy among risk classifications, my former student Zaneta Chapman and I have found it useful to consider the fundamental sources of concern, which can be organized under rubrics of causality, controllability, and social acceptability.9 For each of these categories, I will suggest a spectrum of sociodemographic variables ranked judgmentally from “most controversial” to “least controversial” for each of two important types of personal insurance: individual health and private passenger automobile.

Causality

Causality denotes the degree to which observed correlations between certain characteristics and expected losses arise from a true cause-and-effect relationship that can be used to predict losses effectively. For example, in items one through three above, the relationship between age and automobile insurance losses was questioned based upon doubts concerning, respectively: (1) the presence of a correlation; (2) the presence of actual causation; and (3) the presence of additional sources of causation that were omitted.

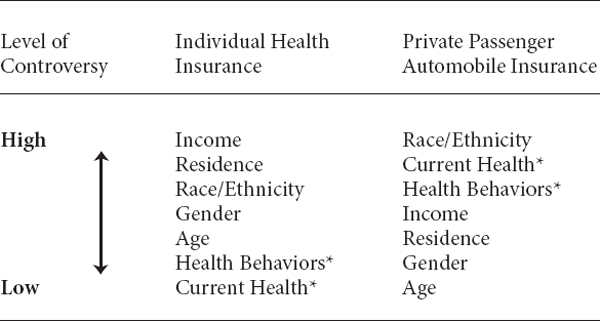

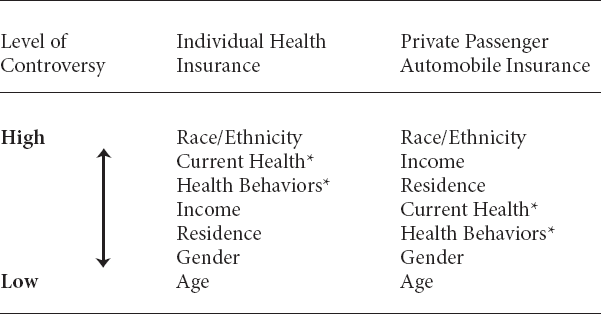

In Table 9.1, I rank by type of insurance seven salient sociodemographic variables by the level of causality-related controversy that they provoke. As already noted, these rankings are based entirely upon judgment; therefore, rather than attempting to justify each particular ranking, I will restrict attention to differences between the two types of insurance.

Unlike the case of health insurance, there is little compelling evidence that Race/Ethnicity, Current Health, and Health Behaviors are direct causal factors of private passenger automobile insurance losses—although if one had to guess, it seems reasonable to believe that certain Health Behaviors (like drinking and smoking) can raise the chance of a collision if they are carried out while driving. Also, it is important to note that the role played by Income in private passenger automobile insurance has more to do with the ability to pay premiums on time and financial incentives for fraud and/or litigation than with the probability of a collision. Residence, however, can impact both the chance of a collision (through association with traffic density) and the potential for fraud and/or litigation (because certain geographic areas are more disposed to this type of activity than others).

Level of Controversy Relating to Causality (Author’s Judgment)

* A distinction is made between Current Health conditions (including genetic predispositions) and Health(-related) Behaviors (such as smoking).

Controllability

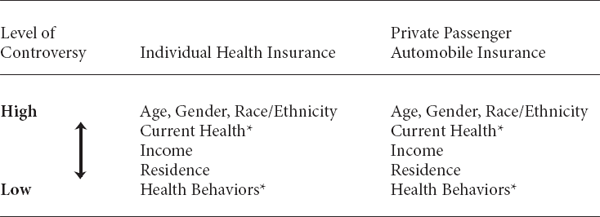

Controllability indicates the degree to which certain characteristics, which may be causally related to expected losses, are subject to change by policyholders that are interested in reducing their expected losses. For example, in item four above, the relationship between age and automobile insurance losses was questioned not for reasons of causality, but rather for the fairness of penalizing younger people for their ages, a characteristic that cannot be changed. In Table 9.2, I judgmentally rank the seven sociodemographic variables from the previous table by the level of controllability-related controversy that they create.

Since a policyholder’s ability to control any particular sociodemographic factor is independent of the type of insurance purchased, the rankings for individual health and private passenger automobile must be identical. One notable difference between Table 9.2 and the prior table is the tie among three variables—Age, Gender, and Race/Ethnicity—at the highest level of controversy.

Level of Controversy Relating to Controllability (Author’s Judgment)

* A distinction is made between Current Health conditions (including genetic predispositions) and Health(-related) Behaviors (such as smoking).

Social Acceptability

Social acceptability describes the degree to which certain characteristics, which may be causally related to expected losses but are not entirely controllable by policyholders, are viewed favorably in terms of normative social welfare considerations. For example, in item five above, the relationship between age and automobile insurance losses was questioned not for reasons of causality or controllability, but rather for the fairness of penalizing younger people, who constitute a less-affluent sociodemographic group. Table 9.3 provides judgmental rankings of the seven variables from the previous two tables by the level of controversy associated with social acceptability.

Although doubts have been raised at one time or another about most sociodemographic variables that are not entirely within the control of policyholders, Age and Gender generally have been found more acceptable than Race/Ethnicity and Income. These determinations probably arise from either (or both) of two considerations:

• the likelihood of implicit cost averaging (in particular, Age may be more acceptable because most individuals are both young and old policyholders at different times of their lives, and Gender may be more acceptable because higher insurance rates for a given sex in one line of business can be offset by lower rates in another line of business); and

• support for social mobility/equality (specifically, Race/Ethnicity and Income may be less acceptable because they are viewed as harming particularly disadvantaged segments of society).

Level of Controversy Relating to Social Acceptability (Author’s Judgment)

* A distinction is made between Current Health conditions (including genetic predispositions) and Health(-related) Behaviors (such as smoking).

In the two rankings of Table 9.3, the only differences are the placements of the variables Current Health and Health Behaviors. These differences are attributable to the fact that policyholders who are vulnerable because of either type of health status are highly likely to lose financially from being unable to purchase affordable individual health insurance, but less likely to lose financially from being unable to purchase affordable private passenger automobile insurance.

ACT 2, SCENE 4

[Offices of Trial Insurance Company. Head clerk sits at desk.]

CLERK: [Mumbles to himself as he reviews document.] Well, this is interesting: an application to insure a house for $500,000, when the house was just purchased for only $300,000. Very suspicious. Perhaps my first chance to use the Other pile?

FORM 1: Please, sir, I beseech you. Don’t place me in the Suspicious pile.

CLERK: [Looks around in all directions.] Excuse me … who is speaking?

FORM 1: I, sir, the application form in your hand.

CLERK: Oh, really? I didn’t realize the paperwork around here was in the habit of remonstrating. But then this is my first day on the job.

FORM 1: I’m sorry to disturb you, sir, but I want to assure you that there’s no need to place me in the Suspicious pile.

CLERK: No need, eh? Hey, wait a minute, how do you know the purpose of the Other pile?

FORM 1: Well, I suppose I just surmised it from what you said: that I appeared to be “very suspicious.”

CLERK: And now you’re talking. That is indeed suspicious. But to get right to the heart of the matter, perhaps you’d care to explain why it is that you’re asking for $500,000 of coverage on a house that’s worth only $300,000.

FORM 1: Well, you see, sir, one can never be too careful. Perhaps the value of the house will increase faster than permitted by your company’s inflation rider.

CLERK: Inflation rider? Uh, this is only my first day here. I’m afraid I’m not quite up to speed on all the relevant insurance jargon. [Relents.] Well, I must admit, you do sound sincere; so I suppose there would be no harm in simply sending you along to Underwriting. They can decide on your final disposition themselves.

FORM 1: Thank you, sir. You are most civilized.

CLERK: You’re very welcome. [Picks up next document from pile.] And what do we have here? A claim form for a house fire—and the claim amount is $500,000. Well, that seems to be a popular figure today. Say, the street address is very familiar. [Gets up from chair to compare claim form with application form in Underwriting pile.] Yes, I thought so. It’s the same as the address on that very polite application form. Now this is definitely suspicious!

FORM 2: [Gruffly.] You won’t put me in the Suspicious pile if you know what’s good for you!

CLERK: What? What did you say? Am I now being threatened by paperwork?

This is certainly unacceptable!

FORM 2: You heard what I said. Unlike those polite application forms, we claim forms don’t mince words. I have powerful friends. If you don’t send me directly to Claim Adjustment, you’ll regret it.

CLERK: Well, this is indeed quite intolerable! Into the Other pile you go! [Places claim form in Other pile.] That’ll teach you to threaten me. [Picks up next document from pile as Boss enters.]

Boss: Is something wrong? I thought I heard shouting.

CLERK: Nothing that I can’t handle. A low-life claim form started making threats, that’s all.

BOSS: Did it really? I’ve been told that Mr. Kafka used to speak of such things; but I always thought he was just being literal.

CLERK: Not to worry, in any case. I put the form in the Other pile.

BOSS: Very good, very good. I’m glad to see you have everything under control. [Begins to leave, then stops, holding out envelope.] Oh, I just received this by special courier. It’s for you.

CLERK: What is it?

BOSS: It appears to be a subpoena of some sort. It seems you’ve been deposed in a legal matter regarding a homeowner’s claim. [Leaves Sorter by himself.]