Marylebone may not have quite the social pedigree of neighbouring Mayfair, but it’s still a wealthy and aspirational area. Compared to the brashness of Oxford Street, which forms its southern border, Marylebone’s backstreets are a pleasure to wander, especially the chi-chi village-like quarter around Marylebone High Street. This is where the city’s leading private specialists in medicine and surgery have had their practices since they gravitated here in the nineteenth century. And it was here that The Beatles (and many others since) took up residence when they hit the big time in the 1960s. The area’s more conventional sights include the free art gallery and aristocratic mansion of the Wallace Collection, Sherlock Holmes’ old stamping ground around Baker Street and the massively touristy Madame Tussauds.

Marylebone was once the outlying village of St Mary-by-the-Bourne (the bourne in question being the Tyburn stream) or St Marylebone (pronounced “marra-le-bun”), and when Samuel Pepys walked through open countryside to reach its pleasure gardens in 1668, he declared it “a pretty place”. During the course of the next century, the gardens were closed and the village was swallowed up as its chief landowners – among them the Portlands and the Portmans – laid out a mesh of uniform Georgian streets and squares, much of which survives today.

DOCTORS AND DENTISTS

Harley Street was an ordinary residential Marylebone street until the nineteenth century when doctors, dentists and medical specialists began to colonize the area in order to serve London’s wealthier citizens. Private medicine survived the threat of the postwar National Health Service, and the most expensive specialists and hospitals are still to be found in the streets around here.

The national dental body, the British Dental

Association (BDA) has its headquarters at nearby 64 Wimpole St, and

a museum (Tues & Thurs 1–4pm; free; ![]() 020

7935 4549,

020

7935 4549, ![]() bda.org;

bda.org; ![]() Bond Street) displaying the gruesome

contraptions of early dentistry, and old prints of agonizing extractions.

Although dentistry is traditionally associated with pain, it was, in fact, a

dentist who discovered the first anaesthetic.

Bond Street) displaying the gruesome

contraptions of early dentistry, and old prints of agonizing extractions.

Although dentistry is traditionally associated with pain, it was, in fact, a

dentist who discovered the first anaesthetic.

Langham Place

North of Oxford Circus, Regent Street forms the eastern border of Marylebone, but stops abruptly at Langham Place, which formed an awkward twist in John Nash’s triumphal route to Regent’s Park in order to link up with the pre-existing Portland Place. Nash’s solution was to build his unusual All Souls Church, now the only Nash building left in this star-studded chicane that’s home to the BBC’s Broadcasting House and the historic Langham Hotel.

All Souls Church

Langham Place • Mon–Sat 9.30am–5.30pm, Sun 9am–2pm &

5.30–8.30pm • Free • ![]() 020 7580 3522,

020 7580 3522, ![]() allsouls.org • _test777

allsouls.org • _test777![]() Oxford Circus

Oxford Circus

John Nash’s simple and ingenious little All Souls Church was built in warm Bath Stone in the 1820s, and is the architect’s only surviving church. The unusual circular Ionic portico and conical stone spire, which caused outrage in its day, are cleverly designed to provide a visual full stop to Regent Street and lead the eye round into Portland Place and ultimately to Regent’s Park.

Broadcasting House

Langham Place • Guided tours Sun; £13.50; no under-9s • ![]() 0370 901 1227,

0370 901 1227, ![]() bbc.co.uk/tours • _test777

bbc.co.uk/tours • _test777![]() Oxford Circus

Oxford Circus

Behind All Souls lies the totalitarian-looking Art Deco Broadcasting House, BBC radio headquarters since 1932. The figures of Prospero and Ariel (pun intended) above the entrance are by Eric Gill, who caused a furore by sculpting Ariel with overlarge testicles, and, like Epstein a few years earlier at Broadway House, was forced in the end to cut the organs down to size. Broadcasting House has recently undergone a £1-billion refurbishment and is now the headquarters of BBC News (both TV and radio) and you can sign up for a guided tour (1hr 30min) to see the state-of-the-art open-plan newsroom, the Radio Theatre and some of the studios.

HIDDEN GEMS: MARYLEBONE

Langham Hotel

Opposite Broadcasting House stands the Langham Hotel, built in grandiose Italianate style and opened by the Prince of Wales in 1865 as the city’s most modern hotel, with over one hundred water closets. It features in several Sherlock Holmes mysteries, and its former guests have included Antonín Dvorák (who courted controversy by ordering a double room for himself and his daughter to save money), exiled emperors Napoleon III and Haile Selassie, Oscar Wilde and the writer Ouida (aka Marie Louise de la Ramée), who threw outrageous parties for young Guards officers and wrote many of her bestselling romances in her dimly lit hotel boudoir. Following World War II, it was taken over by the BBC and used to record legendary shows such as The Goons, only returning to use as a luxury hotel in 1991.

Portland Place

After the chicane around All Souls, you enter Portland Place, laid out by the Adam brothers in the 1770s and incorporated by Nash in his grand Regent Street plan. Once the widest street in London, it’s still a majestic avenue, still lined here and there with Adam-style houses, boasting wonderful fanlights and iron railings. At the northern end of Portland Place, Nash originally planned a giant “circus” as a formal entrance to Regent’s Park. Only the southern half – two graceful arcs of creamy terraces known collectively as Park Crescent – was completed, now cut off from the park by busy Marylebone Road.

Chinese Embassy

Several embassies occupy properties on Portland Place, but the most prominent is the Chinese Embassy at no. 49, opposite which there’s usually a small group of protesters permanently positioned objecting either to Chinese suppression of Falun Gong or its policies in Tibet. It was here in 1896 that the exiled republican leader Sun Yat-sen was kidnapped and held incognito, on the orders of the Chinese emperor. Eventually Sun managed to send a note to a friend, saying “I am certain to be beheaded. Oh woe is me!”. When the press got hold of the story, Sun was finally released; he went on to found the Chinese Nationalist Party and became the first president of China in 1911.

Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA)

66 Portland Place • Mon, Wed & Thurs 8am–7pm, Tues 8am–9pm,

Fri 8am–6pm, Sat 9am–5pm; exhibitions Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • Free • ![]() 020 7580 5533,

020 7580 5533, ![]() architecture.com • _test777

architecture.com • _test777![]() Regent’s Park or Great Portland

Street

Regent’s Park or Great Portland

Street

The Royal Institute of British Architects or RIBA at no. 66 is arguably the finest building on Portland Place, with its sleek Portland-stone facade built in the 1930s amid the remaining Adam houses. The main staircase remains a wonderful period piece, with its etched glass balustrades and walnut veneer, and with two large black marble columns rising up on either side. You can view the interior en route to the institute’s excellent ground-floor bookshop, first-floor exhibition galleries and café.

Wallace Collection

Manchester Square • Daily 10am–5pm • Free • ![]() 020 7563 9500,

020 7563 9500, ![]() wallacecollection.org • _test777

wallacecollection.org • _test777![]() Bond Street

Bond Street

It comes as a great surprise to find the miniature eighteenth-century French chateau of Hertford House in the quiet Georgian streets just to the north of busy Oxford Street. Even more remarkable is the house’s splendid Wallace Collection within, a public museum and art gallery combined, which boasts paintings by Titian, Rembrandt and Velázquez, the finest museum collection of Sèvres porcelain in the world and one of the finest displays of Boulle marquetry furniture, too. The collection was originally bequeathed to the nation in 1897 by the widow of Richard Wallace, an art collector and the illegitimate son of the fourth Marquess of Hertford. The museum has preserved the feel of a grand stately home, an old-fashioned institution with exhibits piled high in glass cabinets and paintings covering every inch of wall space. However, it’s the combined effect of the exhibits set amid superbly restored eighteenth-century period fittings – and a bloody great armoury – that makes the place so remarkable. Labelling is deliberately terse, so as not to detract from the aristocratic ambience, but there are information cards in each room, free highlights tours most days (11.30am & 2.30pm) and themed audioguides available (for a fee).

WALLACE COLLECTION

Ground floor

The ground-floor rooms begin with the Front State Room, to the right as you enter, where the walls are hung with several fetching portraits by Reynolds, and Lawrence’s typically sensuous portrayal of the author and society beauty, the Countess of Blessington, which went down a storm at the Royal Academy in 1822. The decor of the Back State Room is a riot of Rococo, and houses the cream of the house’s gaudily spectacular Sèvres porcelain. Centre stage is a period copy of Louis XV’s desk, which was the most expensive piece of eighteenth-century French furniture ever made. On the other side of the adjacent Dining Room, in the Billiard Room, you’ll find an impressive display of outrageous, gilded oak and ebony Boulle marquetry furniture. From the Dining Room, with its Canalettos, you can enter the covered courtyard, home to The Wallace Restaurant, and head down the stairs to the temporary exhibition galleries and the Conservation Gallery where folk of all ages can try on some medieval armour.

Back on the ground floor, the Sixteenth-Century Gallery displays a wide variety of works ranging from pietre dure, bronze and majolica to Limoges porcelain and Venetian glass. In the Smoking Room, a small alcove at the far end survives to give an idea of the effect of the original Minton-tiled decor Wallace chose for this room. The next three rooms house the extensive European Armoury bought en bloc by Wallace around the time of the Franco-Prussian War. (It was in recognition of the humanitarian assistance Wallace provided in Paris during that war that he received his baronetcy.) A fourth room houses the Oriental Armoury, collected by the fourth Marquess of Hertford, including a cabinet of Asante gold treasure, a sword belonging to Tipu Sultan and one of the most important Sikh treasures in Britain, the sword of Ranjit Singh (1780–1839).

First floor

The main staircase, with its incredible Parisian wrought-iron balustrade and its gilded, fluted columns, is overlooked by Boucher’s sumptuous mythological scenes. In the gloriously camp pink Boudoir, off the landing and conservatory, you’ll find Reynolds’ doe-eyed moppets, while the adjacent passageway boasts an unbelievably rich display of gold snuff boxes and miniatures. The Study features more Sèvres porcelain, Greuze’s soft-focus studies of kids and a lovely portrait by Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, one of the most successful portraitists of pre-Revolutionary France. Next door, in the sky-blue Oval Drawing Room, one of Fragonard’s coquettes flaunts herself to a smitten beau in The Swing, alongside more Boucher nudes – the soft porn of the ancien régime. There’s plenty more Rococo froth in the other rooms on this floor, plus classic Grand Tour vistas from Canaletto and Guardi in the West Room.

In addition to all this French finery a good collection of Dutch paintings hangs in the East Galleries, including de Hooch’s Women Peeling Apples, oil sketches by Rubens and landscapes by Ruisdael, Hobbema and Cuyp. On the opposite side of the house, the West Galleries feature works by the British landscape artist Richard Parkes Bonington and Delacroix, his great friend and admirer.

Great Gallery

Finally, you reach the largest room in the house, the Great Gallery, specifically built by Wallace to display his finest paintings, including works by Murillo and Poussin, several vast Van Dyck portraits, Rubens’ Rainbow Landscape and Frans Hals’ Laughing Cavalier. Here, too, are Perseus and Andromeda, a late work by Titian, and Velázquez’s Lady with a Fan. At one end of the room are three portraits of the actress Mary Robinson as Perdita: one by Romney, one by Reynolds and, best of the lot, Gainsborough’s deceptively innocent portrayal, in which she insouciantly holds a miniature of her lover, the 19-year-old Prince of Wales (later George IV), who is portrayed in a flattering full-length portrait by Lawrence. Look out, too, for Rembrandt’s affectionate portrait of his teenage son, Titus, who helped administer his father’s estate after bankruptcy charges and pre-deceased his father at the age of just 28.

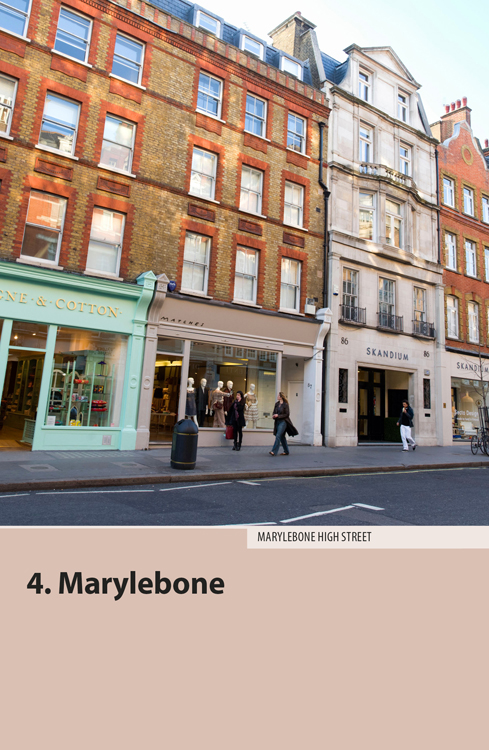

Marylebone High Street

Marylebone High Street is all that’s left of the village street that once ran along the banks of the Tyburn stream. It’s become considerably more upmarket since those bucolic days, though the pace of the street is leisurely by central London standards. A couple of shops, in particular, deserve mention: the branch of Patisserie Valerie, at no. 105, is decorated inside with the same mock-Pompeian frescoes that adorned it when it was founded as Maison Sagne in 1921 by a Swiss pastry-cook; Daunt, a purpose-built bookshop from 1910, at no. 83, specializes in travel books, and has a lovely, long, galleried hall at the back, with a pitched roof of stained glass.

MARYLEBONE STATION

Probably London’s most discreet train terminal, Marylebone Station is hidden in the backstreets north of Marylebone Road on Melcombe Place, where a delicate and extremely elegant wrought-iron canopy links the station to the former Great Central Hotel (now The Landmark). Opened in 1899, Marylebone was the last and most modest of the Victorian terminals, originally intended to be the terminal for the Channel tunnel of the 1880s, a scheme abandoned after only a mile or so of digging, when Queen Victoria got nervous about foreign invasions. The station enjoyed a brief moment of fame after appearing in the opening sequence of The Beatles film A Hard Day’s Night and now serves the Birmingham and Buckinghamshire commuter belt.

St James’s Church, Spanish Place

22 George St • Mon–Fri 7am–7pm, Sat 10am–7pm, Sun

8am–8pm • ![]() 020 7935 0943,

020 7935 0943, ![]() sjrcc.org.uk • _test777

sjrcc.org.uk • _test777![]() Bond Street or Baker Street

Bond Street or Baker Street

Despite its name, St James’s Church, Spanish Place, is actually tucked away on neighbouring George Street, just off Marylebone High Street. A Catholic chapel was built here in 1791 thanks to the efforts of the chaplain at the Spanish embassy, though the present neo-Gothic building dates from 1890. Designed in a mixture of English and French Gothic, the interior is surprisingly large and richly furnished, from the white marble and alabaster pulpit to the richly gilded heptagonal apse. The Spanish connection continues to this day: Spanish royal heraldry features in the rose window, and there are even two seats reserved for the royals, denoted by built-in gilt crowns high above the choir stalls.

Baker Street

Running north–south through Marylebone, Baker Street is a fairly nondescript one-way highway. Despite its unprepossessing nature, its associations with the fictional detective Sherlock Holmes are, naturally, fully exploited. At the northern edge of Marylebone, Baker Street is bisected by the six-lane highway of Marylebone Road. Built as the New Road in the 1750s, to provide London with its first bypass, it remains one of London’s major traffic arteries, and is no place for a casual stroll. There are, however, a couple of minor sights, such as St Marylebone Church and the Royal Academy of Music, and one major tourist trap, Madame Tussauds, that are all an easy stroll from Baker Street tube.

Madame Tussauds

Marylebone Rd • Mon–Fri 9.30am–5.30pm, Sat & Sun

9am–6pm • £30 • ![]() 0871 894 3000,

0871 894 3000, ![]() madametussauds.com • _test777

madametussauds.com • _test777![]() Baker Street

Baker Street

The wax models at Madame Tussauds have been pulling in the crowds ever since the good lady arrived from France in 1802 bearing the sculpted heads of guillotined aristocrats (she was lucky to escape the same fate – her uncle, who started the family business, was less fortunate). The entrance fee might be extortionate and the likenesses dubious, but London’s biggest queues form here – to avoid joining them (and to save money), book online, or whizz round after 5pm for half-price.

There are photo opportunities galore in the first few sections, which are peppered with contemporary celebrities from the BBC to Bollywood. Look out for the diminutive Madame Tussaud herself, and the oldest wax model, Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s mistress, who gently respires as Sleeping Beauty – in reality she was beheaded in the French Revolution. The Chamber of Horrors is irredeemably tasteless, and – in the section called “Scream” – features costumed actors who jump out at you in the dark (you can opt out of this). All the “great” British serial killers are here, and it remains the murderer’s greatest honour to be included. There’s a reconstruction of John Christie’s hanging, a tableau of Marat’s death in the bath and the very guillotine that lopped off Marie Antoinette’s head, just for good measure.

Tussauds also features the Spirit of London, an irreverent five-minute romp through the history of London in a miniaturized taxicab, taking you from Elizabethan times to a postmodern heritage nightmare of tourist tat (not unlike much of London today). The tour of Tussauds ends with a short hi-tech “experience”, often inspired by a recent Hollywood flick, including a 4D 360-degree film projected onto the ceiling of the domed auditorium of the former London Planetarium.

Sherlock Holmes Museum

239 Baker St • Daily 9.30am–6pm • £8 • ![]() 020 7224 3688,

020 7224 3688, ![]() sherlock-holmes.co.uk • _test777

sherlock-holmes.co.uk • _test777![]() Baker Street

Baker Street

Baker Street, which cuts across Marylebone Road, is synonymous with London’s languid super-sleuth, Sherlock Holmes, who lived at no. 221b. The detective’s address was always fictional, although the most likely inspiration was, in fact, no. 21, at the south end of the street. However, the statue of Holmes’s creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, is at the north end of the street, outside Baker Street tube, round the corner from the Sherlock Holmes Museum, at no. 239 (the sign on the door says 221b). Unashamedly touristy – you can have your photo taken in a deerstalker – the museum is nevertheless a competent exercise in period reconstruction, stuffed full of Victoriana and life-size models of characters from the books.

St Marylebone Church

Marylebone Rd • ![]() 020 7935 7315,

020 7935 7315, ![]() stmarylebone.org • _test777

stmarylebone.org • _test777![]() Baker Street or Regent’s Park

Baker Street or Regent’s Park

Completed in 1817, St Marylebone Church is only open fitfully for services and recitals, though the church’s most attractive feature – the gilded caryatids holding up the beehive cupola on top of the tower – is visible from Marylebone High Street. It was at this church that Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning were secretly married in 1846 (there’s a chapel dedicated to Browning), after which Elizabeth – six years older than Robert, an invalid, morphine addict and virtual prisoner in her father’s house on Wimpole Street – returned home and acted as if nothing had happened. A week later the couple eloped to Italy, where they spent most of their married life. The church crypt houses a small chapel, a healing centre, an NHS health centre and a café.

Royal Academy of Music

Marylebone Rd • Mon–Fri 11.30am–5.30pm, Sat noon–4pm • Free • ![]() 020 7873 7373,

020 7873 7373, ![]() ram.ac.uk • _test777

ram.ac.uk • _test777![]() Baker Street or Regent’s Park

Baker Street or Regent’s Park

On the other side of Marylebone Road from St Marylebone Church stands the Royal Academy of Music, which was founded in 1823 and has taught the likes of Arthur Sullivan, Harrison Birtwistle, Dennis Brain, Evelyn Glennie, Elton John, Michael Nyman and Simon Rattle. As well as putting on free lunchtime and evening concerts, the academy houses a small museum at 1 York Gate. Temporary exhibitions are held on the ground floor, while in the String Gallery on the first floor, there’s a world-class collection of Cremonese violins including several by Stradivari. The exhibition on the second floor in the Piano Gallery follows the development of the grand piano in England and gives you a peek into the resident luthier’s workshop. Listening-posts on each floor allow you to experience the instruments in live performance.