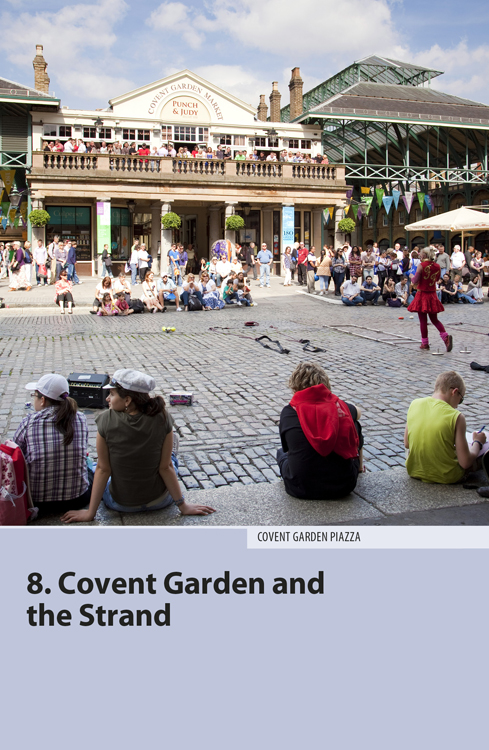

Covent Garden’s transformation from a workaday fruit and vegetable market into a fashionable quartier is one of the most miraculous and successful developments of the 1980s. More mainstream and commercial than neighbouring Soho, it’s also a lot more popular thanks to the buskers, street entertainers and human statues that make the traffic-free Covent Garden Piazza an undeniably lively place to be. As its name suggests, the Strand, on the southern border of Covent Garden, once lay along the riverbank until the Victorians created the Embankment to shore up the banks of the Thames. One showpiece river palace, Somerset House, remains, its courtyard graced by a lovely fountain in summer, and its chambers home to the Courtauld Gallery’s superb collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings.

Covent Garden

Covent Garden has come full circle: what started out in the seventeenth century as London’s first luxury neighbourhood is once more an aspirational place to live, work and shop. Boosted by buskers and street entertainers, the piazza is now one of London’s major tourist attractions, and the streets to the north – in particular, Long Acre, Neal Street and Floral Street – are home to fashionable clothes and shoe shops.

Most visitors are happy enough simply to wander around watching the street life, having a coffee and doing a bit of shopping, but there are a couple of specific sights worth picking out. One of the old market buildings houses the enjoyable London Transport Museum, while another serves as the public foyer for the Royal Opera House and boasts a great roof terrace overlooking the piazza.

COVENT GARDEN’S SHOPPING STREETS

Apple may have arrived on the piazza, but the shopping streets to the north still hold one or two surprises. Floral Street, a quiet cobbled backstreet, running east–west one block north of the piazza, is a good place to start. At the eastern end is a strange helix-shaped walkway connecting the Royal Ballet School with the Royal Opera House. In the western half you can inspect the tongue-in-cheek window displays of three adjoining shops run by top-selling British designer Paul Smith (nos. 40–44). Another quirky outlet is the shop entirely dedicated to Tintin, the Belgian boy-detective (no. 34). Meanwhile, squeezed beside a very narrow alleyway off Floral Street is the Lamb and Flag, the pub where the Poet Laureate, John Dryden, was beaten up in December 1679 by a group of thugs, hired most probably by his rival poet, the Earl of Rochester, who mistakenly thought Dryden was the author of an essay satirizing him.

One block north, Long Acre has long been Covent Garden’s main shopping street, though it originally specialized in coach manufacture. The most famous shop on the street is Stanfords, the world’s oldest and largest map shop, packed to the rafters with Rough Guides. Look out, too, for Carriage Hall, an old stabling yard originally used by coachmakers (now converted into shops), surrounded by cast-iron pillars and situated between Long Acre and Floral Street. Running north from Long Acre, Neal Street features some fine Victorian warehouses, complete with stair towers for loading and shifting goods between floors, from the days of the fruit, vegetable and flower market. The street is currently dominated by shoe stores, with only a few alternative shops left: Food for Thought, the veggie café founded in 1971, is a rare survivor, as is Neal’s Yard, a tiny little courtyard off Shorts Gardens, stuffed with cafés and prettily festooned with flower boxes and ivy.

The piazza

Covent Garden’s piazza – London’s oldest planned square – was laid out in the 1630s, when the Earl of Bedford commissioned Inigo Jones to design a series of graceful Palladian-style arcades based on the main square in Livorno, Tuscany, where Jones had helped build the cathedral. Initially it was a great success, its novelty value alone attracting a plutocratic clientele, but over time the tone of the place fell as the market (set up in the earl’s back garden) expanded and theatres, coffee houses and brothels began to proliferate.

By the onset of the nineteenth century, the market dominated the area, and so in the 1830s a proper market hall was built in the middle of the piazza in the Greek Revival style. A glass roof was added in the late Victorian era, but otherwise the building stayed unaltered until the market’s closure in 1974, and only public protests averted yet another office development. Instead, the elegant market hall and its environs were restored to house shops, restaurants and arts-and-crafts stalls. In its early days, the area had an alternative hippy vibe, a legacy of the area’s numerous squats. Nowadays, upmarket chain stores occupy much of the market hall and the arcades, with the world’s largest Apple Store, on the north side of the piazza, a sign of the how far the area has come from its origins.

COFFEE HOUSES AND BROTHELS

By the eighteenth century the piazza was known as “the great square of Venus”, home to dozens of gambling dens, bawdy houses and so-called “bagnios”. Some bagnios were plain Turkish baths, but most doubled as brothels, where courtesans stood in the window and, according to one contemporary, “in the most impudent manner invited passengers from the theatres into the houses”.

London’s most famous coffee houses were concentrated here, too, attracting writers such as Sheridan, Dryden and Aphra Behn. The rich and famous frequented places like the piazza’s Shakespeare’s Head, whose cook made the best turtle soup in town, and whose head waiter, John Harrison, was believed to be the author of the anonymously published “Who’s Who of Whores”, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, which sold over a quarter of a million copies in its day.

The Rose Tavern, on Russell Street (immortalized in Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress), was one of the oldest brothels in Covent Garden – Pepys mentions “frigging with Doll Lane” at the Rose in his diary of 1667 – and specialized in “Posture Molls”, who engaged in flagellation and striptease, and were deemed a cut above the average whore. Food was apparently excellent, too, and despite the frequent brawls, men of all classes, from royalty to ruffians, made their way there.

St Paul’s Church

Covent Garden Piazza • Mon–Fri 8.30am–5pm, Sat times vary, Sun

9am–1pm • ![]() 020 7836 5221,

020 7836 5221, ![]() actorschurch.org • _test777

actorschurch.org • _test777![]() Covent Garden or Leicester Square

Covent Garden or Leicester Square

Covent Garden piazza is overlooked from the west by St Paul’s Church. The Earl of Bedford allegedly told Inigo Jones to make St Paul’s no fancier than a barn, to which the architect replied, “Sire, you shall have the handsomest barn in England”. It’s better known nowadays as the Actors’ Church, and is filled with memorials to thespians from Boris Karloff to Gracie Fields. The cobbles in front of the church’s Tuscan portico – where Eliza Doolittle was discovered selling violets by Henry Higgins in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion – are now a legalized venue for buskers and street performers, who must audition for a slot.

The piazza’s history of entertainment goes back to May 1662, when the first recorded performance of Punch and Judy in England was staged by Italian puppeteer Pietro Gimonde, and witnessed by Pepys. To celebrate this a Punch and Judy Festival, called May Fayre, is held on the second Sunday in May, in the gardens behind the church; for the rest of the year the churchyard provides a tranquil respite from the activity outside.

London Transport Museum

Covent Garden Piazza • Daily 10am–6pm, Fri from 11am • Adults £15, under-16s free • ![]() 020 7379 6344,

020 7379 6344, ![]() ltmuseum.co.uk • _test777

ltmuseum.co.uk • _test777![]() Covent Garden

Covent Garden

A former flower-market shed on the piazza’s east side houses the ever-popular London Transport Museum. A sure-fire hit for families with kids under 10, it’s a must-see for any transport enthusiast, though restrictions of space mean that there are only a handful of large exhibits.

Still, the story of London’s transport is a fascinating one – to follow it chronologically, head for Level 2, where you’ll find a replica 1829 Shillibeer’s Horse Omnibus, which provided the city’s first regular horse-bus service, and a double-decker horse-drawn tram, introduced in the 1870s. Level 1 tells the story of the world’s first underground system and contains a lovely 1920s Metropolitan Line carriage, fitted out in burgundy and green with pretty, drooping lamps.

Down on the ground floor, the museum’s one double-decker electric tram is all that’s left to pay tribute to the world’s largest tram system, which was dismantled in 1952. Look out, too, for the first tube train, from the 1890s, whose lack of windows earned it the nickname “the padded cell”. Most of the interactive stuff is aimed at kids, but visitors of all ages should check out the tube driver simulator.

A good selection of London Transport’s stylish maps and posters are usually on display, many commissioned from well-known artists, and you can buy copies at the shop on the way out. Real transport enthusiasts should check out the reserve collection at the Museum Depot in Acton (details on the website), which is open occasional weekends throughout the year.

London Film Museum

45 Wellington St • Daily 10am–6pm • Free • ![]() 020 3617 3010,

020 3617 3010, ![]() londonfilmmuseum.com • _test777

londonfilmmuseum.com • _test777![]() Covent Garden

Covent Garden

Such is the success of the main branch of the London Film Museum in County Hall that this satellite museum has opened on the site of the former Theatre Museum. The exhibition is basically a celebratory history of the era of celluloid, which is drawing to a close. It begins with the early experiments in cinema from magic lantern to stereoscopes, and features some of the earliest silent moving pictures ever made. The rest of the displays concentrate on the history of London in film, and are grouped into themed sections – Literary London, Gas-lit London, Wartime London and so on. There are plenty of film clips and stills to keep you amused, but only a handful of artefacts to look at, from Fagin’s gloves and hat to Ali G’s orange shellsuit.

Bow Street

Covent Garden’s dubious reputation was no doubt behind the opening of Bow Street magistrates’ office in 1748. The first two magistrates were Henry Fielding, author of Tom Jones, and his blind half-brother John – nicknamed the “Blind Beak” – who, unusually for the period, refused to accept bribes. Finding “lewd women enough to fill a mighty colony”, Fielding set about creating London’s first police force, the Bow Street Runners. Never numbering more than a dozen, they were employed primarily to combat prostitution, and they continued to exist a good ten years after the establishment of the uniformed Metropolitan Police in 1829. Bow Street police station and magistrates court (both now closed) had the honour of incarcerating Oscar Wilde after he was arrested for “committing indecent acts” in 1895 – he was eventually sentenced to two years’ hard labour. In 1908 Emmeline Pankhurst appeared here, charged with leafleting supporters to “rush” the House of Commons, and, in 1928, Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness was deemed obscene by Bow Street magistrates and remained banned in this country until 1949.

Royal Opera House

Bow St • Foyer: daily 10am–3.30pm • Several tours including backstage tours (1hr 15min) take place regularly and can be booked in advance: Mon–Fri 10.30am, 12.30pm &

2.30pm, Sat 10.30am, 11.30am, 12.30pm & 1.30pm • £12 • ![]() 020 7304 4000,

020 7304 4000, ![]() roh.org.uk • _test777

roh.org.uk • _test777![]() Covent Garden

Covent Garden

The main entrance to the Royal Opera House – a splendid Corinthian portico – stands opposite the former Bow Street magistrates’ court. The original theatre witnessed the premieres of Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Sheridan’s The Rivals before being destroyed by fire in 1808. To offset the cost of rebuilding, ticket prices were increased; riots ensued for 61 performances until the manager finally backed down. The current building dates from 1858, and is the city’s main opera house, home to both the Royal Ballet and Royal Opera. A covered passageway connects the piazza with Bow Street, and allows access to the ROH box office, and upstairs to the beautiful Victorian wrought-iron-and-glass Floral Hall. Continuing up the escalators, you reach the Amphitheatre bar-restaurant, with a fine terrace overlooking the piazza.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP THE MARKET HALL; BALLERINA NEAR ROYAL OPERA HOUSE; THE TEA HOUSE, NEAL ST

Drury Lane

One block east of Bow Street runs Drury Lane, nothing to write home about in its present condition, but in Tudor and Stuart times a very fashionable address. During the Restoration, it became a permanent fixture in London’s theatrical and social life, but by the eighteenth century, it had become a notorious slum rife with prostitution. Nevertheless, it was at no. 179 that J Sainsbury (founder of the supermarket chain) opened his first food store in 1869 – “Quality perfect, prices lower” – and it is here, of course, that the Muffin Man lives in the children’s nursery rhyme.

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

Drury Lane • _test777![]() Covent Garden

Covent Garden

The most famous building in the street is the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane first established here in 1663 – the current theatre (the fourth on the site) dates from 1812, faces onto Catherine Street and currently churns out Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals. It was at the original theatre that women were first permitted to appear on stage in England (their parts having previously been played by boys), but critics were sceptical about their competence at portraying the fairer sex and thought their profession little better than prostitution – most had to work at both to make ends meet (as the actress said to the bishop). The scantily clad women who sold oranges to the audience were considered even less virtuous, the most famous being Nell Gwynne who from the age of 14 was playing comic roles on stage. At the age of 18, she became Charles II’s mistress, the first in a long line of Drury Lane actresses who made it into royal beds.

It was also at the Theatre Royal that David Garrick, as actor, manager and part-owner from 1747, revolutionized the English theatre, treating the text with more reverence than had been customary, insisting on rehearsals and cutting down on improvisations. The rich, who had previously occupied seats on the stage itself, were confined to the auditorium, and the practice of refunding those who wished to leave at the first interval was stopped. However, an attempt to prevent half-price tickets being sold at the beginning of the third act provoked a riot and had to be abandoned. Despite Garrick’s reforms, the Theatre Royal remained a boisterous and often dangerous place of entertainment: George III narrowly escaped an assassination attempt, and ordered the play to continue after the assassin had been apprehended, and the orchestra often had cause to be grateful for the cage under which they were forced to play. The theatre has one other unique feature: two royal boxes, instigated in order to keep George III and his son, the future George IV, apart, after they had a set-to in the foyer.

Freemasons’ Hall

60 Great Queen St • Mon–Fri 10am–5pm • Free • Guided tours Mon–Fri usually 11am, noon, 2, 3

& 4pm; • free • ![]() 020 7395 9257,

020 7395 9257, ![]() freemasonry.london.museum • _test777

freemasonry.london.museum • _test777![]() Covent Garden

Covent Garden

Looking east off Drury Lane, down Great Queen Street, it’s difficult to miss the austere, Pharaonic mass of the Freemasons’ Hall, built as a memorial to all the Masons who died in World War I. Whatever you may think of this reactionary, secretive, male-dominated organization, the interior is worth a peek for the Grand Temple alone, whose pompous, bombastic decor is laden with heavy symbolism. To see the Grand Temple, sign up for one of the guided tours and bring some ID with you. The Masonically curious might also take a look at the shop, which sells Masonic merchandise – aprons, wands, rings and books about alchemy and the cabbala – as do several outlets on Great Queen Street.

The Strand

As its name suggests the Strand – the main road from Westminster to the City – once ran along the banks of the River Thames. From the twelfth century onwards, it was famed for its riverside residences, owned by bishops, noblemen and courtiers, which lined the south side of the street, each with their own river gates opening onto the Thames. In the late 1860s, the Victorians built the Embankment, simultaneously relieving congestion along the Strand, cutting the aristocratic mansions off from the river and providing an extension for the tube and a new sewerage system. By the 1890s, the mansions on the Strand were outnumbered by theatres, giving rise to the music-hall song Let’s All Go Down the Strand (have a banana!), and prompting Disraeli to declare it “perhaps the finest street in Europe”. A hundred years later, several theatres survive, from the sleek Art Deco Adelphi to the Rococo Lyceum, but the only surviving Thames palace is Somerset House, which houses gallery and exhibition space, and boasts a wonderful fountain-filled courtyard.

Charing Cross Station

The Strand begins at Charing Cross Station, fronted by the French Renaissance-style Charing Cross Hotel, built in the 1860s. Standing rather forlorn, in the station’s cobbled forecourt, is a Victorian version of the medieval Charing Cross, removed from nearby Trafalgar Square by the Puritans. The original thirteenth-century cross was the last of twelve erected by Edward I, to mark the overnight stops on the funeral procession of his wife, Eleanor of Castile, from Lincoln to Westminster in 1290.

Zimbabwe House

Opposite Charing Cross Station, on the corner of Agar Street, is the Edwardian-era former British Medical Association building, now Zimbabwe House, housing the Zimbabwean embassy, outside which there are now regular protests against the Mugabe regime. Few passers-by even notice the eighteen naked figures by Jacob Epstein that punctuate the second-floor facade, but at the time of their unveiling in 1908, they caused enormous controversy – “a form of statuary which no careful father would wish his daughter and no discriminating young man his fiancée to see”, railed the press. When the Southern Rhodesian government bought the building in 1937 they pronounced the sculptures to be a health and safety hazard to passers-by, and hacked at the genitals, heads and limbs of all eighteen, which remain mutilated to this day.

The Savoy

Strand • ![]() 020 7836 4343,

020 7836 4343, ![]() fairmont.com/savoy-london • _test777

fairmont.com/savoy-london • _test777![]() Charing Cross or Embankment

Charing Cross or Embankment

On the south side of the Strand, the blind side street of Savoy Court – the only street in the country where the traffic drives on the right – leads to The Savoy, one of London’s grandest hotels, built in 1889 by Richard D’Oyly Carte. César Ritz was the original manager, Auguste Escoffier the chef, who went on to invent the pêche Melba at the hotel. The hotel’s American Bar introduced cocktails into Europe in the 1930s, Guccio Gucci started out as a dishwasher here and the list of illustrious guests is endless: Monet and Whistler both painted the Thames from one of the south-facing rooms, Sarah Bernhardt nearly died here and Strauss the Younger arrived with his own orchestra. It’s worthwhile strolling up Savoy Court to check out the hotel’s Art Deco foyer, the polygonal glass fish fountain and the silver and gold statue of John of Gaunt, whose medieval palace stood on the site. The adjacent Savoy Theatre, with its outrageous 1930s silver and gold fittings, was originally built in 1881 to showcase Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic operas, witnessing eight premieres, including The Mikado – the theatre’s profits helped fund the building of the hotel.

Savoy Chapel

Savoy Hill • Mon–Thurs 9.30am–4pm, Sun

9am–1pm • Free • ![]() 020 7836 7221,

020 7836 7221, ![]() duchyoflancaster.co.uk • _test777

duchyoflancaster.co.uk • _test777![]() Charing Cross or Embankment

Charing Cross or Embankment

Nothing remains of John of Gaunt’s medieval Savoy Palace, which stood here until it was burnt down in the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, though the Savoy Chapel (or The Queen’s Chapel of the Savoy to give its full title), hidden round the back of the hotel down Savoy Street, dates from the time when the complex was rebuilt as a hospital for the poor in 1512. The chapel is much altered, but it became a fashionable venue for weddings when the hotel and theatre were built next door – all three were the first public buildings in the world to be lit by electricity. And talking of lighting, don’t miss the Patent Sewer Ventilating Lamp, erected in the 1880s halfway down Carting Lane, and still powered by methane collected in a U-bend in the sewers below.

Victoria Embankment

To get to the Victoria Embankment, from the Strand, head down Villiers Street, beside Charing Cross Station. Completed in 1870, the embankment was the inspiration of engineer Joseph Bazalgette, who used the reclaimed land for a new tube line, new sewers, and a new stretch of riverside parkland – now filled with an eclectic mixture of statues and memorials from Robbie Burns to the Imperial Camel Corps. The 1626 York Watergate, in the Victoria Embankment Gardens to the east of Villiers Street, gives you an idea of where the banks of the Thames used to be: the steps through the gateway once led down to the river.

Cleopatra’s Needle

London’s oldest monument, Cleopatra’s Needle, languishes little noticed on the Thames side of the busy Victoria Embankment, guarded by two Victorian sphinxes (facing the wrong way). In fact, the 60ft-high, 180-ton stick of granite has nothing to do with Cleopatra – it’s one of a pair erected in Heliopolis (near Cairo) in 1475 BC (the other one is in New York’s Central Park) and taken to Alexandria by Emperor Augustus fifteen years after Cleopatra’s suicide. This obelisk was presented to Britain in 1819 by the Turkish viceroy of Egypt, but nearly sixty years passed before it made the treacherous voyage, in its own purpose-built boat, all the way to London. It was erected in 1878 above a time capsule containing, among other things, the day’s newspapers, a box of hairpins, a railway timetable and pictures of the country’s twelve prettiest women.

Royal Society of Arts (RSA)

6–8 John Adam St • Tours by appointment only • ![]() 020 7930 5115,

020 7930 5115, ![]() thersa.org • _test777

thersa.org • _test777![]() Charing Cross or Embankment

Charing Cross or Embankment

Founded in 1754, the “Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce”, better known now as the Royal Society of Arts or RSA, moved into a purpose-built, elaborately decorated house designed by the Adam brothers in 1774. The building contains a small display on the Adelphi and retains several original Adam ceilings and chimneypieces. The highlight, however, is The Great Room, with six paintings on The Progress of Human Knowledge and Culture by James Barry, forming a busy, continuous pictorial frieze around the room, punctuated by portraits of two early presidents by Reynolds and Gainsborough. The RSA is one of a number of Adam houses that survive from the magnificent riverside development built between 1768 and 1772 by the Adam brothers and known as the Adelphi, which was, for the most part, demolished in 1936.

Benjamin Franklin House

36 Craven St • Architectural tours Mon noon, 1, 2, 3.15

& 4.15pm Historical Experience Wed–Sun noon, 1, 2, 3.15 &

4.15pm • £7 • ![]() 020 7925 1405,

020 7925 1405, ![]() benjaminfranklinhouse.org • _test777

benjaminfranklinhouse.org • _test777![]() Charing Cross or Embankment

Charing Cross or Embankment

From 1757 to 1775, Benjamin Franklin (1706–90) had “genteel lodgings” here. While Franklin was espousing the cause of the British colonies (as the US then was), the house served as the first de facto American embassy; eventually, he returned to America to help draft the Declaration of Independence and frame the US Constitution. On Mondays, the emphasis is on the Benjamin Franklin House’s architecture and restoration, as well as Franklin’s own story. For the Historical Experience, a costumed guide and a series of impressionistic audiovisuals transport visitors back to the time of Franklin, who lived here with his “housekeeper” in cosy domesticity, while his wife and daughter languished in Philadelphia.

Aldwych

The wide crescent of Aldwych, forming a neat “D” on its side with the eastern part of the Strand, was driven through the slums of this zone in the early twentieth century. A confident ensemble occupies the centre, with the enormous Australia House and India House sandwiching Bush House, home of the BBC’s World Service from 1940 to 2012. Despite its thoroughly British associations, Bush House was actually built by the American speculator Irving T. Bush, whose planned trade centre flopped in the 1930s. The giant figures on the north facade and the inscription, “To the Eternal Friendship of English-Speaking Nations”, thus refer to the friendship between the US and Britain, and are not, as many people assume, the World Service’s declaratory manifesto.

Not far from these former bastions of Empire, up Houghton Street, lurks that erstwhile hotbed of left-wing agitation, the London School of Economics. Founded in 1895, the LSE gained a radical reputation in 1968, when a student sit-in protesting against the Vietnam War ended in violent confrontations that were the closest London came to the heady events in Paris that year. Famous alumni include Carlos the Jackal, Cherie Booth (wife of ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair) and Mick Jagger.

Somerset House

Strand • Fountain Court Daily 7.30am–11pm • Free • Riverside terrace Daily 8am–6pm • FreeGuided tours Thurs 1.15 & 2.45pm, Sat

1.15, 2.15, 3.15 & 4.15pm • Free • Embankment galleries Daily 10am–6pm • £6 • ![]() 020 7845 4600,

020 7845 4600, ![]() somersethouse.org.uk • _test777

somersethouse.org.uk • _test777![]() Temple or Covent Garden

Temple or Covent Garden

Somerset House is the sole survivor of the grandiose river palaces that once lined the Strand, its four wings enclosing a large courtyard rather like a Parisian hôtel. Although it looks like an old aristocratic mansion, the present building was, in fact, purpose-built in 1776 by William Chambers, to house governmental offices (including the Navy Office). Nowadays, Somerset House’s granite-paved courtyard is a great place to relax thanks to its fab 55-jet fountain that spouts straight from the cobbles, and does a little syncopated dance every half-hour (daily 10am–11pm). The courtyard is also used for open-air performances, concerts, installations and, in winter, an ice rink.

The north wing houses the permanent collection of the Courtauld Institute, best known for its outstanding Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. The south wing has a lovely riverside terrace with a café-restaurant and the Embankment Galleries, which host innovative special exhibitions on contemporary art and design. Before you head off to one of the collections, however, make sure you go and admire the Royal Naval Commissioners’ superb gilded eighteenth-century barge in the King’s Barge House, below ground level in the south wing.

Courtauld Gallery

Somerset House, Strand • Daily 10am–6pm, occasional Thurs until

9pm • £6 (Mon £3) • ![]() 020 7848 2526,

020 7848 2526, ![]() courtauld.ac.uk • _test777

courtauld.ac.uk • _test777![]() Temple or Covent Garden

Temple or Covent Garden

Founded in 1931 as part of the University of London, the Courtauld Institute was the first body in Britain to award degrees in art history as an academic subject. It’s most famous, however, for the Courtauld Gallery, which displays its priceless art collection, whose virtue is quality rather than quantity. Best known for its superlative Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works, the Courtauld also owns a fine array of earlier works by the likes of Rubens, Botticelli, Bellini and Cranach the Elder and gives regular talks throughout the year.

The displays currently start on the ground floor with a small room devoted to medieval religious paintings. Next, you ascend the beautiful, semicircular staircase to the first-floor galleries, whose exceptional plasterwork ceilings recall their original use as the learned societies’ meeting rooms. This is where the cream of the Courtauld’s collection is currently displayed: rehangings have become more frequent, however, so ask if you can’t find a particular painting.

The first floor galleries

To follow the collection chronologically, start in room 2, where you’ll find two splendid fifteenth-century Florentine cassoni (chests), with their original backrests, and a large Botticelli altarpiece commissioned by a convent and refuge for repentant prostitutes; hence Mary Magdalene’s pole position below the Cross. You can also admire Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve, one of the highlights of the collection, with the Saxon painter revelling in the visual delights of Eden. Works by Rubens dominate room 3, ranging from oil sketches for church frescoes to large-scale late works, plus a winningly informal portrait of his close friend Jan Brueghel the Elder and family. Also in this room hangs Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape with Flight into Egypt, a small canvas once owned by Rubens. Further on, there are works by Goya, Reynolds, Romney, Tiepolo and an affectionate portrait by Gainsborough of his wife, painted in his old age.

The cream of the gallery’s Impressionist works occupy the next few rooms, with room 5 devoted to Cézanne and featuring his characteristically lush landscapes and one of his series of Card Players. The works in room 6 are all by artists who took part in the first Impressionist exhibition in Paris in 1874, and include Renoir’s La Loge, a Monet still-life, and a view of Lordship Lane by Pissarro from his days in exile in London. Also on display are a small-scale version of Manet’s bold Déjeuner sur l’herbe, and his atmospheric A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, a nostalgic celebration of the artist’s love affair with Montmartre, painted two years before his death. In room 7, Gauguin’s Breton peasants Haymaking contrasts with his later Tahitian works, including the sinister Nevermore. And there are works by Van Gogh including his Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear, painted shortly after his remorseful self-mutilation, following his attempted attack on his flatmate Gauguin. Look out, too, for Picasso’s Child with a Dove, from 1901, which heralded his “Blue Period”.

Second floor: twentieth-century works

The second floor is used primarily to display the Courtauld’s twentieth-century works, which bring a wonderful splash of colour and a hint of modernism to the galleries. There isn’t the space to exhibit the entire collection, so it’s impossible to say for definite which paintings will be on show at any one time. Room 8 is home to paintings, sketches and sculptures by Edgar Degas, while in room 9, you hit the bright primary colours of the Courtauld’s superb collection of Fauvist paintings, by the likes of Derain, Vlaminck, Braque, Dufy and Matisse, which spill over into room 10. You’ll also find Yellow Irises, a rare early Picasso from 1901, and one of Modigliani’s celebrated nudes.

The Courtauld owns a selection of works by Roger Fry, who helped organize the first Impressionist exhibitions in Britain, and went on to found the Omega Workshops in 1913 with Duncan Grant. Fry also bequeathed his private collection to the Courtauld, including several paintings by Grant, his wife Vanessa Bell and Fry himself. There’s a room devoted to British artists from the 1930s like Ben Nicolson, Barbara Hepworth and Ivon Hitchens, and at least one room with works by the likes of Kokoschka, Jawlensky, Kirchner, Delaunay and Léger, and an outstanding array of works by Kandinsky, the Russian-born artist who was 30 when he finally decided to become a painter and move to Munich. He’s best known for his pioneering abstract paintings, such as Improvisation on Mahogany from 1910, where the subject matter begins to disintegrate in the blocks of colour.

King’s College

Strand • ![]() 020 7848 2343,

020 7848 2343, ![]() kcl.ac.uk • _test777

kcl.ac.uk • _test777![]() Temple or Covent Garden

Temple or Covent Garden

Adjacent to Somerset House, the ugly concrete facade of King’s College (part of the University of

London) conceals Robert Smirke’s much older buildings, which date from its

foundation in 1829. Rather than entering the college itself, stroll down

Surrey Street and turn right down Surrey Steps, which are in the middle of

the old Norfolk Hotel, whose terracotta facade is

worth admiring. This should bring you out at one of the most unusual sights

in King’s College: the “Roman” Bath, a 15ft-long

tub (actually dating from Tudor times at the earliest) with a natural spring

that produces 2000 gallons a day. It was used in Victorian times as a cold

bath (Dickens himself used it and David Copperfield “had many a cold plunge”

here). The bath is visible through a window (daily 9am–dusk; ![]() 020 7641

5264), but you can only get a closer look by appointment.

020 7641

5264), but you can only get a closer look by appointment.

St Mary-le-Strand

Strand • Tues–Thurs 11am–4pm, Sun 10am–1pm • Free • ![]() 020 7836 3126,

020 7836 3126, ![]() stmarylestrand.org • _test777

stmarylestrand.org • _test777![]() Temple or

Covent Garden

Temple or

Covent Garden

St Mary-le-Strand, completed in 1724 in Baroque style and topped by a delicately tiered tower, was the first public building of James Gibbs, who went on to design St Martin-in-the-Fields. Nowadays, the church sits ignominiously amid the traffic hurtling westwards down the Strand, though even in the eighteenth century, parishioners complained of the noise from the roads, and it’s incredible that recitals are still given here. The entrance is flanked by two lovely magnolia trees, and the interior has a particularly rich plastered ceiling in white and gold. It was in this church that Bonnie Prince Charlie allegedly renounced his Roman Catholic faith and became an Anglican, during a secret visit to London in 1750.

St Clement Danes

Strand • Daily 9am–4pm • Free • ![]() 020 7242 8282,

020 7242 8282, ![]() raf.mod.uk/stclementdanes • _test777

raf.mod.uk/stclementdanes • _test777![]() Temple or Covent Garden

Temple or Covent Garden

St Clement Danes, designed by Wren, occupies a traffic island in the Strand. Badly burnt out in the Blitz (the pock marks are still visible in the exterior north wall), the church was handed over to the RAF, who turned it into a memorial to those killed in World War II. Glass cabinets in the west end of the church contain some poignant mementoes, such as a wooden cross carved from a door hinge in a Japanese POW camp. The nave and aisles are studded with over eight hundred squadron and unit badges, while heavy tomes set in glass cabinets record the 120,000 RAF service personnel who died. The church’s carillon plays out various tunes, including the nursery rhyme Oranges and Lemons (daily 9am, noon, 3, 6 & 9pm), though St Clement’s Eastcheap in the City is more likely to be the church referred to in the rhyme.

In front of the church, the statue of Gladstone, with his four female allegorical companions, is flanked by two air chiefs: Lord Dowding, the man who oversaw the Battle of Britain, and “Bomber” Harris, architect of the saturation bombing of Germany which killed five hundred thousand civilians (and over 55,000 Allied airmen commemorated on the plinth). Although Churchill was ultimately responsible, the opprobrium was left to fall on Harris, who was denied the peerage all the other service chiefs received, while his forces were refused a campaign medal. The statue was unveiled somewhat insensitively, in 1992, on the anniversary of the bombing of Cologne.

Twinings

216 Strand • Mon–Fri 8.30am–7.30pm, Sat 10am–5pm, Sun

10am–4pm • ![]() 020 7383 1359,

020 7383 1359, ![]() twinings.com • _test777

twinings.com • _test777![]() Temple, Chancery Lane or Covent

Garden

Temple, Chancery Lane or Covent

Garden

In 1706, Thomas Twining, tea supplier to Queen Anne, bought Tom’s Coffee House and began serving tea as well as coffee, thereby effectively opening the world’s first tearoom. A branch of Twinings, which sells limited edition long leaf tea, still occupies the site and its slender Neoclassical portico features two reclining Chinamen, dating from the time when all tea came from China. At the back of the shop is a small museum with a fine display of ornate caddies, photos of the Twining family and some historic packaging and advertising.

Lloyd’s Bank (Law Courts branch)

222 Strand • Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri 9am–5pm, Wed

10am–5pm • _test777![]() Temple, Chancery Lane or Covent

Garden

Temple, Chancery Lane or Covent

Garden

Much of the extravagant decor of the short-lived Palsgrave Restaurant, which was built at 222 Strand in 1883, is preserved in Lloyds TSB’s Law Courts branch. The foyer features acres of Doulton tiles, hand-painted in blues and greens, and a flying-fish fountain that was originally supplied with fresh water from an artesian well sunk 238ft below the Strand. The interior of walnut and sequoia wood panelling is worth a look, too, and features ceramic portrait panels. The Law Courts themselves stand opposite.