Clerkenwell

Situated slightly uphill from the City and, more importantly, outside its jurisdiction, Clerkenwell (pronounced “Clark-unwell”) began life as a village serving the various local monastic foundations. In the nineteenth century, the district’s population trebled, mostly through Irish and Italian immigration, and the area acquired a reputation for radicalism exemplified by the Marx Memorial Library, where the exiled Lenin plotted revolution. Nowadays, Clerkenwell is a typical London mix of Georgian and Victorian townhouses, housing estates, old warehouses, loft conversions and art studios. It remains off the conventional tourist trail, but since the 1990s, it has established itself as one of the city’s most vibrant and fashionable areas, with a host of shops, cafés, restaurants and pubs.

Following the Great Fire, Clerkenwell was settled by craftsmen, including newly arrived French Huguenots, excluded from the City guilds. At the same time, the springs that give the place its name were rediscovered (and are still visible through the window of 14–16 Farringdon Lane), and Clerkenwell became a popular spa resort for a century or so. During the nineteenth century, the district’s springs and streams became cholera-infested sewers, and the area became an overpopulated slum area, home to three prisons and the setting for Fagin’s Den in Dickens’ Oliver Twist. Victorian slum clearances and wartime bombing took their toll, the population declined and by the 1980s, the area’s traditional trades – locksmithing, clockmaking, printing and jewellery – all but disappeared. Nowadays, the area is characterized by media and design companies (particularly architects), with trendy bars and restaurants catering for the area’s loft-dwelling residents.

Hatton Garden

Hatton Garden, connecting Holborn Circus with Little Italy, is no beauty spot, but, as the centre of the city’s diamond and jewellery trade since medieval times, it’s an intriguing place to visit during the week. There are over fifty shops and, as in Antwerp and New York, ultra-orthodox Hasidic Jews dominate the business here as middlemen. Near the top of Hatton Garden, there’s a plaque commemorating Hiram Maxim (1840–1916), the American inventor who perfected the automatic gun named after him in the workshops at no. 57.

East of Hatton Garden, off Greville Street, lies Bleeding Heart Yard, a key location in Dickens’ Little Dorrit. The name refers to the gruesome 1626 murder of Lady Hatton, who sold her soul to the devil, so the story goes. One night, during a ball at nearby Hatton House, the devil came to collect, and all trace of her vanished except her heart, which was found bleeding and throbbing on the pavement.

Parallel to Hatton Garden, take a wander through Leather Lane Market, a weekday lunchtime market selling everything from fruit and veg to clothes and electrical gear.

LITTLE ITALY

In the late nineteenth century, London experienced a huge influx of Italian immigrants who created their own Little Italy in the triangle of land now bounded by Clerkenwell Road, Rosebery Avenue and Farringdon Road; craftsmen, artisans, street performers and musicians were later joined by ice-cream vendors, restaurateurs and political refugees. Between the wars the population peaked at around ten thousand, crammed into overcrowded, insanitary slums. The old streets have long been demolished, and few Italians live here these days; nevertheless, the area remains a focus for a community that’s now spread right across the capital.

The main point of reference is St Peter’s Italian

Church (![]() 020 7837 1528,

020 7837 1528, ![]() italianchurch.org.uk), a

surprisingly large, bright, basilica-style church built in 1863 and still

the favourite venue for Italian weddings and christenings, as well as for

Sunday Mass. It’s rarely open outside of daily Mass, though you can view the

World War I memorial in the main porch, and, above it, the grim memorial to

seven hundred Anglo-Italian internees who died aboard the Arandora Star, a POW ship which sank en route to Canada in

1940. St Peter’s is the starting point of the annual Italian Procession, begun in 1883

and a permanent fixture on the Sunday nearest July 16.

italianchurch.org.uk), a

surprisingly large, bright, basilica-style church built in 1863 and still

the favourite venue for Italian weddings and christenings, as well as for

Sunday Mass. It’s rarely open outside of daily Mass, though you can view the

World War I memorial in the main porch, and, above it, the grim memorial to

seven hundred Anglo-Italian internees who died aboard the Arandora Star, a POW ship which sank en route to Canada in

1940. St Peter’s is the starting point of the annual Italian Procession, begun in 1883

and a permanent fixture on the Sunday nearest July 16.

A few old-established Italian businesses survive, too: the Scuola Guida driving school at 178 Clerkenwell Rd, and the deli, G. Gazzano & Son, at 167–169 Farringdon Rd. There’s also a plaque to Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72), the chief protagonist in Italian unification, above the barbers at 10 Laystall St. Mazzini lived in exile in London for many years and was very active in the Clerkenwell community, establishing a free school for Italian children in Hatton Garden.

Mount Pleasant and the British Postal Museum

Rosebery Ave • Postal Museum Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Thurs till 7pm,

plus second Sat of month 10am–5pm (closed the following Mon) • Free • ![]() 020 7239 2570,

020 7239 2570, ![]() postalheritage.org.uk • _test777

postalheritage.org.uk • _test777![]() Farringdon

Farringdon

Halfway up Rosebery Avenue – built in the 1890s to link Clerkenwell Road with

Islington to the north – stands Mount Pleasant,

opened in 1889 and at one time the largest sorting office in the world. A third

of all inland mail passes through here, and originally much of it was brought by

the post office’s own underground railway network, Mail

Rail (![]() mailrail.co.uk). Opened in 1927 and similar in design to the tube, the

railway was fully automatic, sending driverless trucks between London’s sorting

offices and train stations at speeds of up to 35mph. Unfortunately, all 23 miles

of this 2ft-gauge railway were mothballed in 2003. Philatelists, meanwhile,

should head to the British Postal Museum, by the

side of the sorting office on Phoenix Place, which puts on small exhibitions

drawn from its vast archive.

mailrail.co.uk). Opened in 1927 and similar in design to the tube, the

railway was fully automatic, sending driverless trucks between London’s sorting

offices and train stations at speeds of up to 35mph. Unfortunately, all 23 miles

of this 2ft-gauge railway were mothballed in 2003. Philatelists, meanwhile,

should head to the British Postal Museum, by the

side of the sorting office on Phoenix Place, which puts on small exhibitions

drawn from its vast archive.

Exmouth Market

Food market Mon–Fri noon–3pm • ![]() exmouth-market.com • _test777

exmouth-market.com • _test777![]() Farringdon

Farringdon

Opposite Mount Pleasant is Exmouth Market, the heart of today’s vibrant Clerkenwell. Apart from a surviving pie-and-mash shop, the street is now characterized by modish shops, bars and restaurants, and a small foodie market, at its busiest towards the end of the week. A blue plaque at no.56 pays tribute to Joey Grimaldi (1778–1837), son of Italian immigrants and the “Father of Clowns”, who first appeared on stage at nearby Sadler’s Wells at the age of 3. Close by, the street’s Church of the Holy Redeemer sports a fetching Italianate campanile, while the groin-vaulted interior features a large baldachin and stations of the cross – yet despite appearances, it belongs to the Church of England.

Sadler’s Wells

Rosebery Ave • ![]() sadlerswells.com • _test777

sadlerswells.com • _test777![]() Angel

Angel

Clerkenwell’s days as a fashionable spa began when Thomas Sadler rediscovered a medicinal well in his garden in 1683 and established a music house to entertain visitors. The well has since made a comeback at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre on Rosebery Avenue, the seventh theatre here since 1683, and now one of London’s main dance venues. A borehole sunk into the old well provides all non-drinking supplies, helps cool the building and produces bottled drinking water for the punters.

Islington Museum

245 St John St • Daily except Wed & Sun 10am–5pm • Free • ![]() 020 7527 2837 • _test777

020 7527 2837 • _test777![]() Angel or Farringdon

Angel or Farringdon

If you’re keen to learn some more about Clerkenwell, Finsbury or the wider borough of Islington, it’s worth seeking out the Islington Museum, housed in the basement of the Finsbury Library (access is down the steps on the north side). There’s a dressing-up box for the kids and some fascinating sections on the area’s radical politics for the adults. Highlights include the bust of Lenin, part of a memorial designed by Lubetkin, that was erected in 1942 in Holford Square, but had to be removed after the war, after it was targeted by Fascists; you can also view some of the library books embellished by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell.

THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF FINSBURY

The Borough of Finsbury was subsumed into Islington in 1965, but the former Finsbury Town Hall (now a dance academy) still stands, an attractive building from 1899, whose name is spelt out in magenta glass on the delicate wrought-iron canopy that juts out into Rosebery Avenue. As the plaque outside states, the district was the first to boast an Asian MP, Dadabhai Nairoji, who was elected (after a recount) as a Liberal MP in 1892 with a majority of five. In keeping with its radical pedigree, the borough went on to elect several Communist councillors and became known popularly as the “People’s Republic of Finsbury”. The council commissioned Georgian-born Berthold Lubetkin to design the modernist Finsbury Health Centre on Pine Street, off Exmouth Market, described by Jonathan Glancey as “a remarkable outpost of Soviet thinking and neo-Constructivist architecture in a part of central London wracked with rickets and TB”. Lubetkin’s later Spa Green Estate, the council flats further north on the opposite side of Rosebery Avenue from Sadler’s Wells, featured novelties such as rubbish shutes and an aerofoil roof to help tenants dry their clothes.

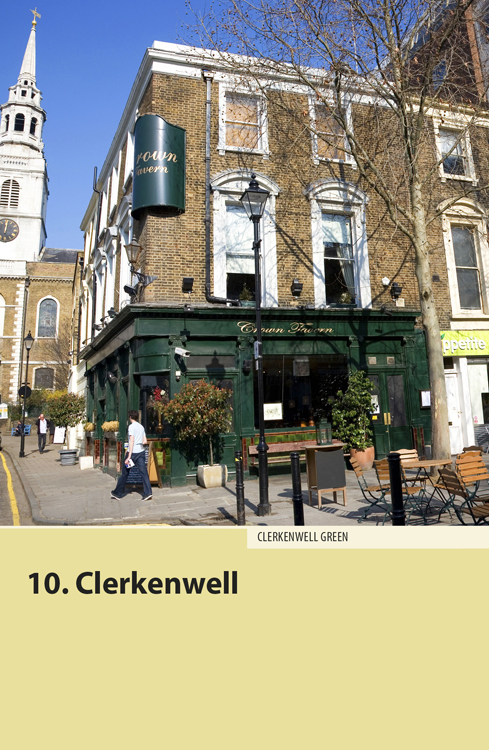

Clerkenwell Green

There hasn’t been any green on Clerkenwell Green for at least three centuries. By contrast, poverty and overcrowding were the main features of nineteenth-century Clerkenwell, and the Green was well known in the press as “the headquarters of republicanism, revolution and ultra-non-conformity” and a popular spot for demonstrations. The most violent of these was the “Clerkenwell Riot” of 1832, when a policeman was stabbed to death during a clash between unemployed demonstrators and the newly formed Metropolitan Police Force. In 1871, a red flag was flown from a lamppost on the Green in support of the Paris Commune. London’s first May Day march set off from here in 1890, and the tradition continues to this day. In 1900, the Labour Party was founded at a meeting on nearby Farringdon Road; in 1903 Lenin and Stalin first met at the Crown & Anchor (now the Crown Tavern); the Communist Party had its headquarters close by on St John Street for many years; and the Party’s Daily Worker (and later Morning Star), The Guardian and The Observer were all printed on Farringdon Road.

LENIN IN CLERKENWELL

Virtually every Bolshevik leader spent at least some time in exile in London at the beginning of the twentieth century, to avoid the attentions of the Tsarist secret police. Lenin (1870–1924) and his wife, Nadezhda, arrived in April 1902 and found unfurnished lodgings at 30 Holford Square, off Great Percy Street, under the pseudonyms of Mr and Mrs Jacob Richter. Like Marx, Lenin did his studying in the British Library – L13 was his favourite desk.

The couple also entertained other exiles – including Trotsky, whom Lenin met for the first time at Holford Square in October 1902 – but Lenin’s most important job was his editing of Iskra with Yuli Martov (later the Menshevik leader) and Vera Zasulich (one-time revolutionary assassin). The paper was set in Cyrillic script at a Jewish printer’s in the East End and run off on the Social Democratic Federation presses on Clerkenwell Green.

In May 1903, Lenin left to join other exiles in Geneva, though over the next eight years he visited London on five more occasions. The Holford Square house was destroyed in the Blitz, so, in 1942, the local council erected a (short-lived) monument to Lenin (now in the Islington Museum). A blue plaque at the back of the hotel on the corner of Great Percy Street commemorates the site of 16 Percy Circus, where Lenin stayed in 1905.

Marx Memorial Library

37a Clerkenwell Green • Mon–Thurs 1–2pm or by appointment; closed

Aug • Free • ![]() 020 7253 1485,

020 7253 1485, ![]() marx-memorial-library.org • _test777

marx-memorial-library.org • _test777![]() Farringdon

Farringdon

The oldest building on the Green is the former Welsh Charity School, at no. 37a, built in 1738 and now home to the Marx Memorial Library. Headquarters of the left-wing London Patriotic Society from 1872, and later the Social Democratic Federation’s Twentieth Century Press, this is where Lenin edited seventeen editions of the Bolshevik paper Iskra in 1902–03. The library itself, founded in 1933 in response to the book burnings in Nazi Germany, is open to members only. However, visitors are welcome to view the “workerist” Hastings Mural from 1935, and the poky little back room where Lenin worked on Iskra. Stuffed with busts, the latter is maintained as a kind of shrine, and there’s a copy of Rodchenko’s red-and-black chess set for good measure, too.

St James’s Church

Clerkenwell Close • Mon–Fri 9.30am–5.30pm • Free • ![]() 020 7251 1190,

020 7251 1190, ![]() jc-church.org • _test777

jc-church.org • _test777![]() Farringdon

Farringdon

The area north of Clerkenwell Green was once occupied by the Benedictine nunnery of St Mary. The buildings have long since vanished, though the current church of St James on Clerkenwell Close, from 1792, is the descendant of the convent church. A plain, galleried building decorated in Wedgwood blue and white, its most interesting features are the twin staircases for the galleries at the west end, both of which were fitted with wrought-iron guards to prevent parishioners from glimpsing any ladies’ ankles as they ascended.

St John’s Gate

St John’s Lane • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • Free • ![]() 020 7324 4005,

020 7324 4005, ![]() museumstjohn.org.uk • _test777

museumstjohn.org.uk • _test777![]() Farringdon

Farringdon

St John’s Gate was built in Kentish ragstone in 1502 as the southern entrance to the Priory of the Order of St John of Jerusalem, the oldest of Clerkenwell’s religious establishments. The Knights of St John, or Knights Hospitaller, were responsible for the defence of the Holy Land, and the Clerkenwell priory was established as the order’s headquarters in the 1140s. The priory was sacked by Wat Tyler’s poll-tax rebels in 1381 on the lookout for the prior, Robert Hales, who was responsible for collecting the tax; Hales was eventually discovered at the Tower, dragged out and beheaded on Tower Hill. Following the Reformation, the Knights moved to Malta, and the Gate housed the Master of Revels, the Elizabethan censor, and later a Latin-speaking coffee house run by Richard Hogarth, father of the painter, William. Today, the gatehouse is the headquarters of the St John Ambulance, a voluntary first-aid service, established in 1877.

The main room of the gatehouse museum traces the development of the Order before its expulsion in 1540 by Henry VIII. There’s masonry from the old priory, crusader coins and a small arms collection salvaged from the knights’ armoury on Rhodes. The museum’s other gallery tells the story of the St John Ambulance, featuring a display of early uniforms and equipment. And if you’re lucky, there’ll be a uniformed nurse on hand to bring the exhibition to life.

Crypt of the Grand Priory Church

Guided tours Tues, Fri & Sat 11am & 2.30pm • £5 donation requested

Of the original twelfth-century church, all that remains is the Norman crypt, which contains two outstanding monuments: a sixteenth-century Spanish alabaster effigy of a Knight of St John, and the emaciated effigy of the last prior, who died of a broken heart in 1540 following the Order’s dissolution. Above ground, the curve of the church’s walls – it was circular, like Temple Church – is traced out in cobblestones on St John’s Square. To visit the Grand Priory Church, you must take a guided tour, which also allows you to explore the gatehouse, including the mock-medieval Chapter Hall.

Charterhouse

Charterhouse Square • By guided tour only April–Aug by

appointment • £10 • ![]() 020 7253 9503,

020 7253 9503, ![]() thecharterhouse.org • _test777

thecharterhouse.org • _test777![]() Barbican or Farringdon

Barbican or Farringdon

In the southeast corner of Clerkenwell lies Charterhouse, founded in 1371 as a Carthusian monastery. The Carthusians were the most respected of the religious orders in London and the only one to put up any significant resistance to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, for which the prior was hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn, and his severed arm nailed to the gatehouse as a warning to the rest of the community. The gatehouse, on Charterhouse Square, which retains its fourteenth-century oak doors, is the starting point for the excellent, exhaustive two-hour guided tours.

Very little remains of the original buildings, as the monastery was rebuilt as a Tudor mansion after the Dissolution. The monks lived in individual cells, each with its own garden and were only allowed to speak to one another on Sundays; three of their tiny cells can still be seen in the west wall of Preachers’ Court. The larger of the two enclosed courtyards, Masters’ Court, retains the wonderful Great Hall, which boasts a fine Renaissance carved screen and a largely reconstructed hammerbeam roof, as well as the Great Chamber where Elizabeth I and James I were once entertained. The Chapel, with its geometrical plasterwork ceiling, is half-Tudor and half-Jacobean, and contains the marble and alabaster tomb of Thomas Sutton, whose greyhound-head emblem crops up throughout the building. It was Sutton, deemed “the richest commoner in England” at the time, who bought the place in 1611 and converted it into a charity school for boys (now the famous public school in Surrey) and an almshouse for gentlemen – known as “brothers” – forty of whom continue to be cared for here.