The South Bank

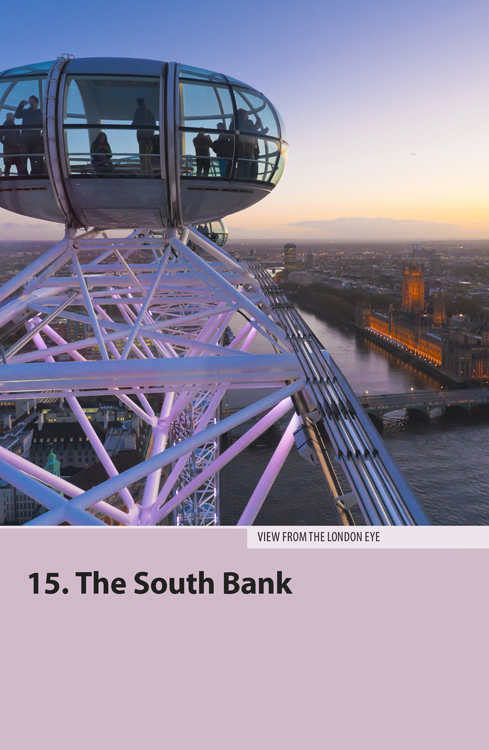

The South Bank has a lot going for it. As well as the massive waterside arts centre, it’s home to a host of tourist attractions including the enormously popular London Eye, Europe’s largest observation wheel, the London Aquarium and, further south, the Imperial War Museum, which harbours the country’s only permanent exhibition devoted to the Holocaust. With most of London’s major sights sitting on the north bank of the Thames, the views from here are the best on the river, and thanks to the wide, traffic-free riverside boulevard, the area can be happily explored on foot. Buskers congregate here to entertain the crowds, and for much of the year there’s some kind of outdoor festival going on along the riverbank. You can continue your wanderings eastwards along the riverside towards Tate Modern and the regenerated districts of Bankside and Southwark.

For centuries London stopped southwards at the Thames; the South Bank was a

marshy, uninhabitable place, a popular place for duck-shooting, but otherwise seldom

visited. Then, in the eighteenth century, wharves began to be built along the

riverbank, joined later by factories, so that by 1905 the Baedeker guidebook

characterized Lambeth and Southwark as “containing

numerous potteries, glass-works, machine-factories, breweries and hop-warehouses”.

Slums and overhead railway lines added to the grime until 1951, when a slice of

Lambeth’s badly bombed riverside was used as a venue for the Festival of Britain,

the site eventually evolving into the Southbank

Centre, a vibrant arts complex, encased in an unlovely concrete shell.

What helped kick-start the South Bank’s more recent rejuvenation was the arrival of

the spectacular London Eye, and the renovation of

Hungerford Bridge, which is now flanked by a

majestic symmetrical double-suspension footbridge, called the Golden Jubilee

Bridges. To get the local view on the area and find out about the latest events on

the South Bank (and in neighbouring Southwark), visit ![]() london-se1.co.uk.

london-se1.co.uk.

Southbank Centre

In 1951, the South Bank Exhibition, on derelict land south of the Thames, formed the centrepiece of the national Festival of Britain, an attempt to boost postwar morale by celebrating the centenary of the Great Exhibition (when Britain really did rule over half the world). The most striking features of the site were the Ferris wheel (now reincarnated as the London Eye), the saucer-shaped Dome of Discovery (inspiration for the Millennium Dome), the Royal Festival Hall (which still stands) and the cigar-shaped steel and aluminium Skylon tower.

The great success of the festival eventually provided the impetus for the creation of the Southbank Centre comprising the Royal Festival Hall, Queen Elizabeth Hall, the Purcell Room and the Hayward Gallery, all squeezed between Hungerford and Waterloo bridges. Unfortunately, however, it failed to capture the imagination of the public in the same way, and became London’s much unloved culture bunker. The low point came in the 1980s when hundreds of homeless lived under the complex in a “Cardboard City”. Since then, there have been considerable improvements, and the centre’s unprepossessing appearance is softened, too, by its riverside location, its avenue of trees, fluttering banners, regular “pop up” festivals and food stalls, occasional buskers and skateboarders, and the weekend secondhand bookstalls outside nearby BFI Southbank. The nearest tube is Waterloo, but the most pleasant way to approach the Southbank Centre is via Hungerford Bridge from Embankment or Charing Cross tube.

Royal Festival Hall

Southbank Centre • Poetry Library Tues–Sun 11am–8pm • Free • ![]() poetrylibrary.org.uk • _test777

poetrylibrary.org.uk • _test777![]() Waterloo

Waterloo

The only building left from the 1951 Festival of Britain is the Royal Festival Hall or RFH, one of London’s main concert venues, whose auditorium is suspended above the open-plan foyer – its curved roof is clearly visible above the main body of the building. The interior furnishings remain fabulously period, and exhibitions and free events in the foyer – the Clore Ballroom – are generally excellent, making this one of the most pleasant South Bank buildings to visit. You can also kill time before a concert in the little-known Poetry Library on Level 5, where you can either browse or, by joining (membership is free), borrow from the library’s vast collection of poetry accumulated since 1912.

Queen Elizabeth Hall and Hayward Gallery

Hayward Gallery Mon noon–6pm, Tues, Wed, Sat

& Sun 10am–6pm, Thurs & Fri 10am–8pm • From £10 • ![]() 020 7960 4200 • _test777

020 7960 4200 • _test777![]() Waterloo

Waterloo

Architecturally, the most depressing parts of the Southbank Centre are the Queen Elizabeth Hall (QEH) and the more intimate Purcell Room, which share the same foyer and are built in uncompromisingly brutalist 1960s style. Immediately above, and equally stark from the outside, is the Hayward Gallery, a large and flexible art gallery that puts on temporary art exhibitions, mostly (but not exclusively) modern or contemporary art. Not surprisingly then, there are currently £120-million plans afoot to transform this area into a new Festival Wing, with more cafés, a rooftop garden and clearer access from the rest of the centre.

Waterloo Bridge to Blackfriars Bridge

Waterloo Bridge, famous for being built mostly by women during World War II, marks the eastern limit of the Southbank Centre, but the next stretch of riverside to Blackfriars Bridge has cultural attractions of its own: from the city’s leading arts cinema, BFI Southbank, to the retail-workshops of the renovated Oxo Tower. The bridge itself was the scene of the assassination of Georgi Markov, a Bulgarian dissident working at the BBC World Service, in 1978. He was shot in the leg with a ricin pellet fired from an umbrella by a member of the Bulgarian secret police and died three days later.

BFI Southbank

Belvedere Rd • Mediathèque Tues–Fri noon–8pm, Sat & Sun

12.30–8pm • Free • ![]() 020 7928 3232,

020 7928 3232, ![]() bfi.org.uk • _test777

bfi.org.uk • _test777![]() Waterloo

Waterloo

Tucked underneath Waterloo Bridge is BFI Southbank, which screens London’s most esoteric films, hosts a variety of talks, lectures and mini-festivals and also runs Mediathèque, where you can settle into one of the viewing stations and choose from a selective archive of British films, TV programmes and documentaries. The BFI also runs the BFI IMAX, housed within the eye-catching glass drum, which rises up from the old “Bull Ring” beneath the roundabout at the southern end of Waterloo Bridge. Boasting the largest screen in the country, it’s definitely worth experiencing a 3D film here at least once.

National Theatre

South Bank • Backstage tours Mon–Fri 6 daily, Sat 2 daily, Sun 1

daily; 1hr 15min • £8.50 • ![]() 020 7452 3400,

020 7452 3400, ![]() nationaltheatre.org.uk • _test777

nationaltheatre.org.uk • _test777![]() Waterloo

Waterloo

Just east of Waterloo Bridge, looking like a multistorey car park, is Denys Lasdun’s National Theatre (officially the Royal National Theatre). An institution first mooted in 1848, it was only finally realized in 1976, and, like the Southbank Centre, its concrete brutalism tends to receive a lot of critical flak, with Prince Charles likening it to a nuclear power station. That said, the three auditoriums within are superb, and the backstage tours here are excellent and popular, so book in advance if possible.

Gabriel’s Wharf

East of the National Theatre, the riverside promenade brings you

eventually to Gabriel’s Wharf, an ad hoc

collection of lock-up craft shops, brasseries and bars that has a small

weekend craft market. It’s a refreshing change from the franchises which

have colonized much of the South Bank, and one for which Coin Street Community Builders (CSCB; ![]() coinstreet.org) must be

thanked. With the population in this bomb-damaged stretch of the South Bank

down from fifty thousand at the beginning of the century to four thousand in

the early 1970s, big commercial developers were keen to step in and build

hotels and office blocks galore. They were successfully fought off, and

instead the emphasis has been on projects that combine commercial and

community interests.

coinstreet.org) must be

thanked. With the population in this bomb-damaged stretch of the South Bank

down from fifty thousand at the beginning of the century to four thousand in

the early 1970s, big commercial developers were keen to step in and build

hotels and office blocks galore. They were successfully fought off, and

instead the emphasis has been on projects that combine commercial and

community interests.

OXO Tower

South Bank • Exhibition Gallery

Daily 11am–6pm • Free • Public viewing gallery

Daily 10am–10pm • Free • _test777![]() Blackfriars

Blackfriars

East of Gabriel’s Wharf stands the landmark OXO Tower, an old power station that was converted into a meat-packing factory in the late 1920s by Liebig Extract of Meat Company, best known in Britain as the makers of OXO stock cubes. To get round the local council’s ban on illuminated advertisements, the company cleverly incorporated the letters into the windows of the main tower, and then illuminated them from within. Now, thanks again to CSCB, the building contains an exhibition gallery on the ground floor, plus flats for local residents and a series of retail-workshops for designers on the first and second floors, and a swanky restaurant, bar and brasserie on the top floor. To enjoy the view, however, you don’t need to eat or drink here: you can simply take the lift to the eighth-floor public viewing gallery.

Waterloo station

Built in 1848, Waterloo Station is easily the capital’s busiest train and tube station, serving the city’s southwestern suburbs and the southern Home Counties. Its two finest features are easily missed: the station’s ornate Edwardian-style facade is hidden behind the railway bridge on Mepham Street, while the snake-like, curving roof of the former Eurostar terminal, designed by Nicholas Grimshaw in 1993, is tucked away on the west side of the station.

Without doubt Waterloo’s most bizarre train terminus was the former London Necropolis Station, whose early twentieth-century facade survives at 121 Westminster Bridge Rd, to the south of the station. Opened in 1854 following one of London’s worst outbreaks of cholera, trains from this station took coffins and mourners to Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey (at the time, the world’s largest cemetery). Brookwood Station even had separate platforms for Anglicans and Nonconformists and a licensed bar – “Spirits served here”, the sign apparently read – but the whole operation was closed down after bomb damage in World War II.

Heading west from the main station concourse, an overhead walkway heads off to the South Bank, passing through the Stalinist-looking Shell Centre. Officially and poetically entitled the Downstream Building, it was built in the 1950s – and was the tallest building in London at the time – by oil giant Shell, which started life as a Jewish East End business importing painted seashells in 1833. Shell have recently sold the building on, and the main tower is set to be at the centre of a new high-rise housing development, partly Qatari-funded and due for completion in 2019.

London Eye

Daily April–June 10am–9pm; July & Aug

10am–9.30pm; Sept–March 10am–8.30pm • From £17 online • ![]() 0871 781 3000,

0871 781 3000, ![]() londoneye.com • _test777

londoneye.com • _test777![]() Waterloo or Westminster

Waterloo or Westminster

Despite only gracing the skyline for a decade or so, the London Eye has secured its place as one of the city’s most famous landmarks. Standing an impressive 443ft high, it’s the tallest Ferris wheel in Europe, weighing over 2000 tons, yet as simple and delicate as a bicycle wheel. It’s constantly in slow motion, which means a full-circle “flight” in one of its 32 pods (one for each of the city’s boroughs) should take around thirty minutes – that may seem a long time, though in fact it passes incredibly quickly. Not surprisingly, you can see right out to the very edge of the city – bring some binoculars if you can – where the suburbs slip into the countryside, making the wheel one of the few places (apart from the Shard or a plane) from which London looks a manageable size. Book online (to save money) – on arrival, you’ll still have to queue to be loaded on unless you’ve paid extra for fast track – or you’ll have to buy your ticket from the box office at the eastern end of County Hall.

County Hall

The colonnaded crescent of County Hall is the only truly monumental building on the South Bank. Designed to house the London County Council, it was completed in 1933 and enjoyed its greatest moment of fame in the 1980s as the headquarters of the GLC (Greater London Council), under the Labour leadership of Ken Livingstone, or “Red Ken”, as the right-wing press called him at the time. The Tories moved in swiftly, abolishing the GLC in 1986, and leaving London as the only European city without an elected authority. In 2000, Livingstone had the last laugh when he became London’s first popularly elected mayor, and head of the new Greater London Authority (GLA), housed in City Hall, near Tower Bridge. The building’s tenants are constantly changing, but it’s currently home to, among other things, several hotels and restaurants, an aquarium and an amusement arcade. None of the attractions that have gravitated here is an absolute must, and several have fallen by the wayside, but they prosper (as do the numerous buskers round here) by feeding off the vast captive audience milling around the London Eye.

London Aquarium

County Hall • Mon–Thurs 10am–6pm, Fri–Sun 10am–7pm • From around £21 online • Snorkelling with Sharks Daily 11.30am, 1.30 &

3.30pm; £125 • ![]() 0871 663 1678,

0871 663 1678, ![]() visitsealife.com/London • _test777

visitsealife.com/London • _test777![]() Waterloo or Westminster

Waterloo or Westminster

The most enduring County Hall tenant is the Sea Life London Aquarium, housed in the basement across three subterranean levels. With some super-large tanks, and everything from dog-face puffers and piranhas to robot fish (seriously) and crocodiles, this is an attraction that’s pretty much guaranteed to please kids, albeit at a price (book online to save a few quid and avoid queuing, or save over a fiver by buying an after 3pm ticket). Impressive in scale, the aquarium boasts a thrilling Shark Walk, in which you have sharks swimming underneath you, as well as a replica blue whale skeleton encasing an underwater walkway. Ask at the main desk or check the website for details of the daily presentations and feeding times and if money’s no object and fear’s not in your vocabulary, enquire about the Snorkelling with Sharks Experience.

London Dungeon

County Hall • Mon–Wed & Fri 10am–5pm, Thurs 11am–5pm,

Sat & Sun 10am–6pm; school holidays closes 7pm • From £22 online • ![]() 0871 423 2240,

0871 423 2240, ![]() thedungeons.com • _test777

thedungeons.com • _test777![]() Waterloo or Westminster

Waterloo or Westminster

The latest venture to join in the shenanigans at County Hall is the London Dungeon, a Gothic horror-fest that remains one of the city’s major crowd-pleasers – to shorten the amount of time spent queuing (and save money), buy your ticket online. Young teenagers and the credulous probably get the most out of the various ludicrous live action scenarios, each one hyped up by the team of ham actors dressed in period garb. These are followed by a series of fairly lame horror rides such as “Henry’s Wrath Boat Ride” and “Drop Dead Drop Ride”, not to mention the latest “Jack the Ripper” experience.

London Film Museum

County Hall • Mon–Wed & Fri 10am–5pm, Thurs 11am–5pm,

Sat 10am–6pm, Sun 11am–6pm • £13.50 • ![]() 020 7202 7040,

020 7202 7040, ![]() londonfilmmuseum.com • _test777

londonfilmmuseum.com • _test777![]() Waterloo or Westminster

Waterloo or Westminster

The London Film Museum occupies a labyrinth of rooms on the first floor of County Hall. It’s not a particularly hi-tech exhibition, so the main draw is really the vast array of props and costumes from Hollywood franchises like Alien, Star Wars and Batman. And there’s a firmly British bent to the place, with each exhibit chosen either because the studio, the designer, the writer or the director was a Brit. Appropriately enough, there’s a whole section on Charlie Chaplin, a local Lambeth boy born in the borough in 1889, and naturally enough there’s a room of Harry Potter props, from the Tri-Wizard Cup to Hogwarts school uniforms. The museum also regularly features special exhibitions on recent film releases with a British connection.

North Lambeth

South of Westminster Bridge, you leave the South Bank proper behind (and at the same time lose the crowds) and head upstream to what used to be the village of Lambeth (now a large borough stretching south to Brixton and beyond). Vestiges of village atmosphere are notably absent, although Lower Marsh with its weekday market and The Cut retain a local feel and have avoided the plague of the franchises that characterizes the South Bank. A few minor sights are worth considering, such as Lambeth Palace and the Garden Museum, and it’s from this stretch of the riverbank that you get the best views of the Houses of Parliament. Inland lies London’s most even-handed military museum, the Imperial War Museum, which has a moving permanent exhibition devoted to the Holocaust.

Florence Nightingale Museum

Lambeth Palace Rd • Daily 10am–5pm • £5.80 • ![]() 020 7620 0374,

020 7620 0374, ![]() florence-nightingale.co.uk • _test777

florence-nightingale.co.uk • _test777![]() Lambeth North, Waterloo or

Westminster

Lambeth North, Waterloo or

Westminster

On the south side of Westminster Bridge, a series of red-brick Victorian blocks and modern white accretions make up St Thomas’ Hospital, founded in the twelfth century, but only established here after being ejected from its original location by London Bridge in 1862, when the railway came sweeping through Southwark. At the hospital’s northeastern corner, off Lambeth Palace Road, is the Florence Nightingale Museum, celebrating the devout woman who single-mindedly revolutionized the nursing profession by establishing the first school of nursing at St Thomas’ in 1860 and publishing her Notes on Nursing, emphasizing the importance of hygiene, decorum and discipline. The exhibition is imaginatively set out, aided by audioguides in the shape of a stethoscope. It hits just the right note by putting the two years she spent tending to the wounded of the Crimean War in the context of a lifetime of tireless social campaigning. Exhibits include the Turkish lantern she used in Scutari hospital, near Istanbul, that earned her the nickname “The Lady with the Lamp”, and her pet owl, Athena (now stuffed), who used to perch on her shoulder.

Lambeth Palace

Lambeth Palace Rd • Certain Thurs & Fri 10.30am &

2pm • £10 • ![]() 0844 248 5134,

0844 248 5134, ![]() archbishopofcanterbury.org • _test777

archbishopofcanterbury.org • _test777![]() Westminster, Lambeth North or

Vauxhall

Westminster, Lambeth North or

Vauxhall

A short walk south of St Thomas’ stands the imposing red-brick Tudor Gate of Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury since 1197. The whole complex is well worth a visit, although guided tours are extremely popular, so you’ll need to book in advance.

The most impressive room is, without doubt, the Great Hall (now the library), with its very late Gothic, oak hammerbeam roof, built after the Restoration by Archbishop Juxon, whose coat of arms, featuring African heads, can be seen on the bookshelves. Upstairs, the Guard Room boasts an even older, arch-braced timber roof from the fourteenth century, and is the room where Thomas More was brought for questioning before being sent to the Tower (and subsequently beheaded).

Among the numerous portraits of past archbishops, look out for works by Holbein, Van Dyck, Hogarth and Reynolds. The final point on the tour is the palace chapel, where the religious reformer and leader of the Lollards, John Wycliffe, was tried (for the second time) in 1378 for “propositions, clearly heretical and depraved”. The door and window frames date back to Wycliffe’s day, but the place is somewhat overwhelmed by the ceiling frescoes by Leonard Rosoman, added in the 1980s, telling the story of the Church of England. Best of all is the fact that you can see the choir screen and stalls put there in the 1630s by Archbishop Laud, and later used as evidence of his Catholic tendencies at his trial (and execution) in 1645.

Garden Museum

Lambeth Palace Rd • Mon–Fri & Sun 10.30am–5pm, Sat

10.30am–4pm; closed first Mon of month • £5 • ![]() 020 7401 8865,

020 7401 8865, ![]() gardenmuseum.org.uk • _test777

gardenmuseum.org.uk • _test777![]() Westminster, Lambeth North or

Vauxhall

Westminster, Lambeth North or

Vauxhall

Next door to Lambeth Palace stands the Kentish ragstone church of St Mary-at-Lambeth, largely rebuilt in Victorian times, but retaining its fourteenth-century tower. The church is now home to the Garden Museum which puts on excellent exhibitions on a horticultural theme in the ground-floor galleries, and has a small permanent exhibition in the “belvedere”, reached by a new wooden staircase. There’s a section on the two John Tradescants (father and son), gardeners to James I and Charles I, who are both buried in the churchyard. You can even view one of the Tradescants’ curiosities – a “vegetable lamb” that’s in fact a Russian fern – plus a few dibbers and grubbers, and some pony boots designed to prevent damage to your lawn.

You can visit the church’s shop and café for free – what’s more you can take your tea and cake out into the small graveyard, now laid out as a seventeenth-century knot garden, where two interesting sarcophagi lurk among the foliage. The first, topped by an ornamental breadfruit, is the resting place of Captain Bligh of Mutiny on the Bounty fame. More intriguing is the Tradescant memorial which features several very unusual reliefs: a seven-headed griffin contemplating a skull and a crocodile sifting through sundry ruins flanked by gnarled trees. The Tradescants were tireless travellers in their search for new plant species, and John the Elder set up a museum of curiosities known as “Tradescant’s Ark” in Lambeth in 1629. Among the many exhibits were the “hand of a mermaid…a natural dragon, above two inches long…blood that rained on the Isle of Wight…and the Passion of Christ carved very daintily on a plumstone”. The less fantastical pieces formed the nucleus of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum.

Imperial War Museum

Lambeth Rd • Daily 10am–6pm • Free • ![]() 020 7416 5000,

020 7416 5000, ![]() london.iwm.org.uk • _test777

london.iwm.org.uk • _test777![]() Lambeth North or Elephant &

Castle

Lambeth North or Elephant &

Castle

From 1815 until 1930, the domed building at the east end of Lambeth Road was the infamous lunatic asylum of Bethlem Royal Hospital, better known as Bedlam. (Charlie Chaplin’s mother was among those confined here – the future comedian was born and spent a troubled childhood in nearby Kennington.) When the hospital was moved to Beckenham in southeast London, the wings of the 700ft-long facade were demolished, leaving just the central section, now home to the Imperial War Museum, by far the capital’s best military museum. The IWM has recently been refurbishing its permanent galleries, while continuing to stage superb long-term temporary exhibitions – its busy schedule of talks and films are well worth checking out.

The main galleries

The treatment of the subject is impressively wide-ranging and fairly sober, once you’ve passed through the Large Exhibits Gallery, with its militaristic display of guns, tanks, fighter planes and a giant V-2 rocket. The galleries on the lower ground floor have been expensively refurbished, and catalogue the human damage of the last century of conflict, in particular the two World Wars. On the first floor, you’ll find the permanent Secret War gallery, which follows the clandestine activities of MI5, MI6 and the SOE (the wartime equivalent of MI6) – expect exploding pencils, trip wires and spy cameras – though its finale is marred by an unrealistically glowing account of recent SAS operations in the Gulf.

The art galleries and Extraordinary Heroes

The museum’s art galleries, on the second floor, put on superb exhibitions taken from their vast collection of works by war artists, official and unofficial, including the likes of David Bomberg, Wyndham Lewis, Stanley Spencer and John Nash. One painting that’s on permanent display in its own room, alongside three other similarly grand canvases, is Gassed, by John Singer Sargent, a painter better known for his portraits of society beauties.

Crimes Against Humanity, also on the second floor, features a harrowing half-hour film on genocide and ethnic violence in the last century. You can also pay a visit to the nearby Explore History Centre and peruse the museum’s reference books, archive film clips and its online collection. On the top floor, the Extraordinary Heroes exhibition displays the largest collection of Victoria Crosses in the world. However, this is much more than a medal gallery as touch-screen computers tell the moving stories behind the decorations.

The Holocaust Exhibition

Many people come to the Imperial War Museum specifically to see the Holocaust Exhibition (not recommended for under-14s), which you enter from the third floor. Taking a fairly conventional, sober approach to the subject, the museum has made a valiant attempt to avoid depicting the victims of the Holocaust as nameless masses, by focusing on individual cases, and interspersing the archive footage with eyewitness accounts from contemporary survivors.

The exhibition pulls few punches, bluntly stating that the pope failed to denounce the anti-Jewish Nuremberg Laws, that writers such as Eliot and Kipling expressed anti-Semitic views, and that at the 1938 Evian Conference, the European powers refused to accept any more Jewish refugees. Despite the restrictions of space, there are sections on the extermination of the gypsies, Nazi euthanasia, pre-Holocaust Yiddish culture and the persecution of the Slavs. The genocide, which began with the Einsatzgruppen and ended with the gas chambers, is catalogued in painstaking detail, while the problem of “proving” the Final Solution is also addressed, in a room that emphasizes the complexity of the Nazi bureaucracy, which, allied to an ideology of extermination, made the Holocaust not just possible but inevitable.

The centrepiece of the museum is a vast, all-white, scale model of (what is, in fact, only a very small slice of) Auschwitz-Birkenau, showing what happened to the two thousand Hungarian Jews who arrived at the camp from the town of Beregovo in May 1944. The significance of this transport is that, uniquely, photographs taken by the SS, of the selection process meted out on these particular arrivals managed to survive the war. In the alcoves overlooking the model, which has a pile of discarded possessions from the camps as its backdrop, survivors describe their first impressions of Auschwitz. This section is especially harrowing, and it’s as well to leave yourself enough time to listen to the reflections of camp survivors at the end, as they attempt to come to terms with the past.