High Street Kensington to Notting Hill

Despite the smattering of aristocratic mansions and the presence of royalty in Kensington Palace, the village of Kensington remained surrounded by fields until well into the nineteenth century. The village has disappeared entirely now in the busy shopping district around Kensington High Street, and the chief attractions are the wooded Holland Park and the former artists’ colony clustered around the exotically decorated Leighton House. Bayswater and Notting Hill, to the north, were for many years the bad boys of the borough, dens of vice and crime comparable to Soho. Gentrification has changed them beyond all recognition, though they remain more cosmopolitan districts, with a strong Arab presence and vestiges of the African-Caribbean community who initiated and still run the Notting Hill Carnival, one of Europe’s largest street festivals.

High Street Kensington

The village of Kensington was centred on Kensington Church Street, but once the area was transformed into a residential suburb in the nineteenth century, the commercial centre shifted to Kensington High Street – better known as High Street Ken, after the tube. The street is dominated architecturally by the twin presences of George Gilbert Scott’s neo-Gothic church of St Mary Abbots (whose 250ft spire makes it London’s tallest parish church) and the Art Deco colossus of Barkers department store, remodelled in the 1930s. The rest of the street is nothing special, but in the quieter backstreets, you’ll find one or two hidden gems like Holland Park, the former gardens of an old Jacobean mansion, and Leighton House, the perfect Victorian artist’s pad.

Kensington Roof Gardens

99 Kensington High St • ![]() 020 7937 7994 for opening

hours,

020 7937 7994 for opening

hours, ![]() roofgardens.virgin.com • _test777

roofgardens.virgin.com • _test777![]() High Street Kensington

High Street Kensington

A little-known feature of the High Street is Europe’s largest Roof Gardens, which tops the former Derry &

Toms department store, another monster 1930s building, next door to Barkers.

Virgin, who now own the gardens, use them for events including a summer

cinema (![]() rooftopfilmclub.com), so phone ahead to check they’re open; to

gain access, head for the side entrance on Derry Street and take the lift.

The nightclub at the centre of the garden is pretty tacky, but the

mock-Spanish convent, the formal gardens, the four pink flamingos, sundry

ducks and the views across the rooftops are surreal.

rooftopfilmclub.com), so phone ahead to check they’re open; to

gain access, head for the side entrance on Derry Street and take the lift.

The nightclub at the centre of the garden is pretty tacky, but the

mock-Spanish convent, the formal gardens, the four pink flamingos, sundry

ducks and the views across the rooftops are surreal.

Kensington Square

On the south side of the High Street lies Kensington Square, an early piece of speculative building laid out in 1685. Luckily for the developers, royalty moved into Kensington Palace shortly after its construction, and the square soon became so fashionable that it was dubbed the “old court suburb”. By the nineteenth century, the courtiers had moved out and the bohemians had moved in: Thackeray wrote Vanity Fair at no. 16; the Pre-Raphaelite painter Burne-Jones lived at no. 41; the actress Mrs Patrick Campbell, for whom George Bernard Shaw wrote Pygmalion, lived at no. 33; and composer Hubert Parry (of Jerusalem fame) gave music lessons to Vaughan Williams at no. 17. John Stuart Mill, philosopher and champion of women’s suffrage, lived next door, and it was here that the first volume of Thomas Carlyle’s sole manuscript of The French Revolution was accidentally used by a maid to light the fire.

Holland Park

Daily 7.30am to dusk • Free • ![]() rbkc.gov.uk • _test777

rbkc.gov.uk • _test777![]() High Street Kensington

High Street Kensington

Hidden away in the backstreets north of High Street Kensington is the

densely wooded Holland Park, popular with

the neighbourhood’s army of nannies and au pairs, who take their charges to

the excellent adventure playground. To get there, take one of the paths

along the east side of the former Commonwealth

Institute – a bold 1960s building with a startling tent-shaped

Zambian copper roof – which will house the Design

Museum from 2015. The park is laid out in the former grounds of

Holland House – only the east wing of

the Jacobean mansion could be salvaged after World War II, but it gives an

idea of what the place used to look like. A youth hostel is linked to the east wing; the garden

ballroom houses the spectacular Belvedere

restaurant; and throughout the summer outdoor

performances take place (![]() operahollandpark.com),

continuing a tradition which stretches back to the first Lady Holland, who

put on plays here in defiance of the puritanical laws of Cromwell’s

Commonwealth. Several formal gardens are laid out

before the house, drifting down in terraces to the arcades, the orangery and

the ice house, which have been converted into a café and an art gallery. The

most unusual of the formal gardens, which are peppered with modern

sculpture, is the Kyoto Garden, a

Japanese-style sanctuary to the northwest of the house, complete with koi

carp and peacocks.

operahollandpark.com),

continuing a tradition which stretches back to the first Lady Holland, who

put on plays here in defiance of the puritanical laws of Cromwell’s

Commonwealth. Several formal gardens are laid out

before the house, drifting down in terraces to the arcades, the orangery and

the ice house, which have been converted into a café and an art gallery. The

most unusual of the formal gardens, which are peppered with modern

sculpture, is the Kyoto Garden, a

Japanese-style sanctuary to the northwest of the house, complete with koi

carp and peacocks.

Holland Park artists’ colony

Several wealthy Victorian artists rather self-consciously founded an artists’ colony around the fringes of Holland Park, and a number of their highly individual mansions are still standing. First and foremost is Leighton House, now a museum. Leighton’s neighbours included G.F. Watts and Holman Hunt, Marcus Stone, illustrator of Dickens, and, in the most outrageous house of all, architect William Burges, who designed his own medieval folly, the Tower House, at 29 Melbury Rd, now owned by Led Zeppelin guitarist, Jimmy Page. Slightly further afield, at 8 Addison Rd, is the Arts and Crafts Debenham House, designed by Halsey Ricardo in 1906 for the department-store Debenham family. The exterior is covered with peacock-blue and emerald-green tiles and bricks; the interior, which features a wonderful neo-Byzantine domed hall, is even more impressive. Sadly, both houses are closed to the public.

Leighton House Museum

12 Holland Park Rd • Daily except Tues 10am–5.30pm • £5 • ![]() 020 7602 3316,

020 7602 3316, ![]() rbkc.gov.uk • _test777

rbkc.gov.uk • _test777![]() High Street Kensington

High Street Kensington

Leighton House, the “House Beautiful”, was built for Frederic Leighton, president of the Royal Academy and the only artist to be made a peer (albeit on his deathbed). “It will be opulence, it will be sincerity”, the artist opined before starting work on the house in the 1860s.

The entrance hall, with its walls of peacock-blue de Morgan tiles, is wonderfully lugubrious, but the star attraction is the remarkable domed Arab Hall, built in 1877. Based on a Moorish palace in Palermo, it resounds to the trickle of a central black marble fountain, and is decorated with Saracen tiles, gilded mosaics and latticework drawn from all over the Islamic world. The other rooms are less spectacular in comparison, but are hung with excellent paintings by Lord Leighton and his Pre-Raphaelite friends, Burne-Jones, Alma-Tadema, Watts and Millais – there’s even a Tintoretto. Skylights brighten the upper floor, which contains a lovely gilded boudoir looking down onto the Arab Hall and Leighton’s vast studio, where he used to hold evening concerts.

18 Stafford Terrace

18 Stafford Terrace • Guided tours

Wed 11.15am &

2.15pm, Sat & Sun 11.15am, 1, 2.15 &

3.30pm • £8 • ![]() 020 7602 3316,

020 7602 3316, ![]() rbkc.gov.uk • _test777

rbkc.gov.uk • _test777![]() High Street Kensington

High Street Kensington

18 Stafford Terrace is where the successful Punch cartoonist, Linley Sambourne, lived until his death in 1910. A grand, though fairly ordinary stuccoed terrace house by Kensington standards, it’s less a tribute to the artist (though it does contain a huge selection of Sambourne’s works) and more a showpiece for the Victorian Society, which helps maintain the house in all its cluttered, late-Victorian excess, complete with stained glass, heavy furnishings and richly decorative William Morris wallpaper. The ninety-minute guided tours are great fun, and, on weekend afternoons, are led by an actor in period garb; there are also occasional evening tours which re-create a night in with the Sambournes.

Bayswater and Paddington

It wasn’t until the removal of the gallows at Tyburn that the area to the north of Hyde Park began to gain respectability. The arrival of the Great Western Railway at Paddington in 1838 further encouraged development, and the gentrification of Bayswater, the area immediately north of the park, began with the construction of an estate called Tyburnia. These days Bayswater is mainly residential, and a focus for London’s widely dispersed Arab community, who are catered for by some excellent restaurants and cafés along the busy Edgware Road.

Paddington Station

Paddington Station, on Praed Street, is one of the world’s great early train stations: the 1850s facade of the station hotel has been mucked about with over the years and lost its charm, but cathedral-scale wrought-iron sheds, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, are looking better than ever. An earlier wooden structure was the destination of Victoria and Albert’s first railway journey in 1842. The train, pulled by the engine Phlegethon, travelled at an average speed of 44mph, which the prince consort considered excessive – “Not so fast next time, Mr Conductor”, he is alleged to have remarked. To the north and east of Paddington is Paddington Basin, built as the terminus of the Grand Union Canal in 1801. Now regenerated, it’s worth exploring if only to admire the trio of unusual footbridges which span the water. Funkiest of the lot is Thomas Heatherwick’s Rolling Bridge, a hydraulic gangway that coils up into an octagon rather like a curled-up woodlouse – it curls up every Friday at noon. If you follow the basin to the northwest, you’ll reach Little Venice in about five minutes.

Fleming Museum

Praed St • Mon–Thurs 10am–1pm • £4 • ![]() 020 3312 6528,

020 3312 6528, ![]() imperial.nhs.uk • _test777

imperial.nhs.uk • _test777![]() Paddington

Paddington

One block east of Paddington up Praed Street is St Mary’s Hospital, home of the Fleming Museum, on the corner of Norfolk Place, where the young Scottish bacteriologist Alexander Fleming accidentally discovered penicillin in 1928. A short video, a small exhibition and a reconstruction of Fleming’s untidy lab tell the story of the medical discovery that saved more lives than any other during the last century. Oddly enough, it aroused little interest at the time, until a group of chemists in Oxford succeeded in purifying penicillin in 1942. Desperate for good news in wartime, the media made Fleming a celebrity, and he was eventually awarded the Nobel Prize, along with several of the Oxford team.

Queensway

Bayswater’s main drag is Queensway, a cosmopolitan street peppered with Middle Eastern cafés. Queensway is best known, however, for Whiteley’s, opened in 1885 as the city’s first real department store or “Universal Provider” with the boast that it could supply “anything from a pin to an elephant”. The present building opened in 1907, and in the same year was the scene of the murder of the store’s founder, William Whiteley, by a man claiming to be his illegitimate son. Whiteley’s also had the dubious distinction of being Hitler’s favourite London building – he planned to make it his HQ once the invasion was over. The store closed in 1981, and now houses shops, restaurants and a multiscreen cinema, but the original wrought-iron staircase, centaurs’ fountain and glass-domed atrium all survive.

St Sophia’s Cathedral

Moscow Rd • Tues–Fri 11am–2pm • Free • ![]() 020 7229 7260,

020 7229 7260, ![]() stsophia.org.uk • _test777

stsophia.org.uk • _test777![]() Queensway or Bayswater

Queensway or Bayswater

Hidden away up Moscow Road, off Queensway itself, is the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of St Sophia, built in 1882 by John Oldrid Scott (son of George Gilbert Scott of St Pancras fame). From the red-brick exterior, you only get the merest hint of the richly decorated atmospheric, candlelit interior, where every surface is covered in polychrome marble and gilded mosaics by, among others, Boris Anrep. Services are well worth attending as the cathedral has a polyphonic choir and afterwards, on the last Sunday of the month, you can visit the treasury in the crypt where there’s a small museum.

Notting Hill

Notting Hill is home to one of London’s most popular markets, Portobello Road, and its most famous annual street festival, the Notting Hill Carnival. It’s also one of the city’s most affluent neighbourhoods, characterized by leafy avenues, private garden squares, trendy shops and white stuccoed mansions. Back in the 1950s, however, it was described as “a massive slum, full of multi-occupied houses, crawling with rats and rubbish”. Along with Brixton in south London, it was one of the main neighbourhoods settled by Afro-Caribbean immigrants, invited over to work in the public services. Tensions between the black families who’d moved into the area and the young white working-class “Teddy Boys” were exploited by far-right groups. And for four days in August 1958, Pembridge Road became the focal point of the UK’s first race riots.

The following year, the Notting Hill Carnival was begun as a response to the riots; in 1965 it took to the streets and has since grown into one of Europe’s biggest street festivals. In the 1970s and early 1980s, tensions between the black community and the police came to a head at carnival time, but strenuous efforts on both sides have meant that such conflict has generally been avoided in the last two decades.

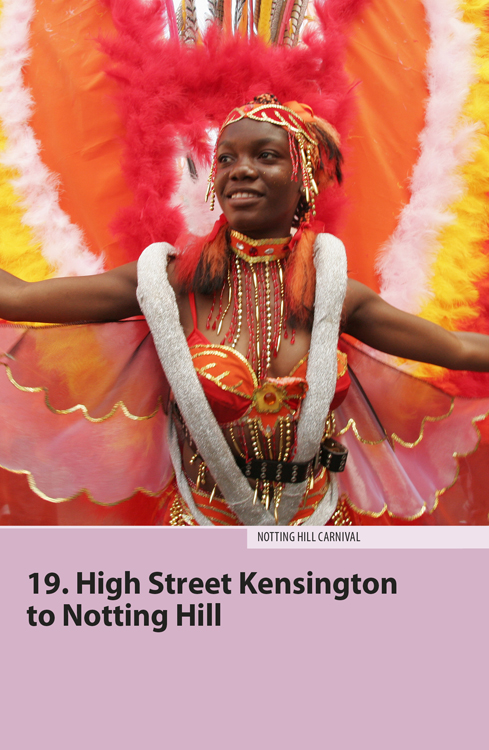

NOTTING HILL CARNIVAL

When it emerged in the 1960s, Notting Hill Carnival was little more than a few church-hall events and a carnival parade by Trinidadians. Today Carnival, held over the August Bank Holiday weekend, still belongs to West Indians (from all parts of the city), but there are participants too from London’s Latin American and Asian communities, and Londoners of all descriptions turn out to watch the bands and parades, drink Red Stripe, eat curry goat and generally hang out.

The main sights of Carnival are the costume parades, which take place on the Sunday (for kids) and Monday (for adults) from around 9am until 7pm. The parade makes its way around a three-mile route, and consists of big trucks which carry the soundsystems and mas (masquerade) bands, behind which the masqueraders dance in outrageous costumes. Most of the mas bands play a variety of soca or calypso featuring steel bands – the “pans” of the steel bands are one of the chief sounds of Carnival and have their own contest on the Saturday at Horniman’s Pleasance, off Kensal Road by the canal. As well as the parade, there are several stages for live music and numerous soundsystems where you can catch reggae, ragga, drum’n’bass, jungle, garage, house and much more.

Over the last decade or so, the Carnival has generally been fairly relaxed, considering the huge numbers of people it attracts. However, this is not an event for you if you’re at all bothered by very loud music or crowds – around a million people attend the festival each year and you can be wedged stationary during the parades. It’s also worth taking more than usual care with yourself and your belongings. The static soundsystems are switched off at 7pm each day – if there’s going to be any trouble it tends to come after that point or, if you feel at all uneasy, head home early.

Getting to and from the Carnival is quite an event

in itself. Ladbroke Grove tube station is closed for the duration, while

other stations have restricted hours or are open only for incoming visitors.

The event’s website ![]() thenottinghillcarnival.com provides helpful advice on how to plan

your journey to and from the carnival.

thenottinghillcarnival.com provides helpful advice on how to plan

your journey to and from the carnival.

Portobello Road

Portobello Road is a meandering, beguiling street that starts just up Chepstow Road from the tube and is famed for its market, at its busiest on Saturdays. A short distance up the road stands the Electric Cinema, London’s oldest movie house, which opened in 1910 on the corner of Blenheim Crescent. Portobello Road is the chief location in the movie Notting Hill: Hugh Grant’s travel bookshop is at 142 Portobello Rd (now a shoe shop), though the real Travel Bookshop is actually round the corner at 13–15 Blenheim Crescent, his house is nearby at 280 Westbourne Park Rd and the private gardens he and Julia Roberts break into are on Rosmead Road.

Trellick Tower

Passing under the Westway flyover and east into Golborne Road, you come face-to-face with the awesome Trellick Tower, a 31-floor high-rise block of flats designed by Ernö Goldfinger in 1973. The separate service tower has arrow slits and an overhanging boiler tower, yet despite its uncompromising concrete brutalist appearance, it remains popular with its residents. Golborne Road itself is known for its Portuguese and Moroccan cafés, giving the road some of the bohemian feel of old Notting Hill, and making it the perfect place to wind up a visit to the market.

Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising

2 Colville Mews • Tues–Sat 10am–6pm, Sun 11am–5pm • £6.50 • ![]() 020 7908 0880,

020 7908 0880, ![]() museumofbrands.com • _test777

museumofbrands.com • _test777![]() Notting Hill Gate

Notting Hill Gate

Despite its rather unwieldy title, it’s definitely worth popping into the Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising, hidden away off Lonsdale Road, one block east of Portobello Road. The museum houses an awesome array of old British shop displays through the decades, based on the private collection of Robert Opie, a Scot whose compulsive collecting disorder has left him with ten thousand yoghurt pots alone. From Victorian ceramic pots of anchovy paste to the alcopops of the 1990s, the displays provide a fascinating social commentary on the times. Look out for the militarization of marketing during the two world wars, with their bile beans “for radiant health and a lovely figure” and V for Victory mugs, and clock the irony of the glamorous early cigarette adverts or the posters for Blackpool “for happy, healthy holidays”.

Kensal Green Cemetery

April–Sept Mon–Sat 9am–6pm, Sun 10am–6pm;

Oct–March closes 5pm • Free • Guided tours March–Oct Sun 2pm; Nov–Feb first & third

Sun 2pm • £7 donation suggested • ![]() 020 8969 0152,

020 8969 0152, ![]() kensalgreen.co.uk • _test777

kensalgreen.co.uk • _test777![]() Kensal Green

Kensal Green

Beside the gasworks, the Great Western Railway and the Grand Union Canal, lies Kensal Green Cemetery, the first of the city’s commercial graveyards, opened in 1833 to relieve the pressure on overcrowded inner-city churchyards. Highgate may be the most famous of the “Magnificent Seven” Victorian cemeteries, but Kensal Green has by far the best funerary monuments. It’s still owned by the founding company and remains a functioning cemetery, with services conducted daily in the central Greek Revival Anglican chapel. The excellent guided tours of the cemetery also include a visit to the catacombs (bring a torch).

The graves of the more famous incumbents – Thackeray, Trollope and the Brunels – are less interesting architecturally than those arranged on either side of the Centre Avenue, which leads from the easternmost entrance on Harrow Road. Vandals have left numerous headless angels and irreparably damaged the beautiful Cooke family monument, but still worth looking out for are Major-General Casement’s bier, held up by four grim-looking turbaned Indians, circus manager Andrew Ducrow’s conglomeration of beehive, sphinx and angels, and artist William Mulready’s neo-Renaissance extravaganza. Other interesting characters buried here include Walter Clopton Wingfield, who invented lawn tennis; Marcus Garvey, the black nationalist (until exhumed and taken to Jamaica in 1964); Charles Blondin, the famous tightrope walker; Carl Wilhelm Siemens, the German scientist who brought electric lighting to London; and “James” Barry, Inspector-General of the Army Medical Department, who, it was discovered during the embalming of the corpse, was in fact a woman. Playwright Harold Pinter was buried here and Queen singer Freddie Mercury was cremated here, but his ashes were scattered in Mumbai. Mary Seacole, the “black Florence Nightingale”, is buried in the adjacent Roman Catholic cemetery.