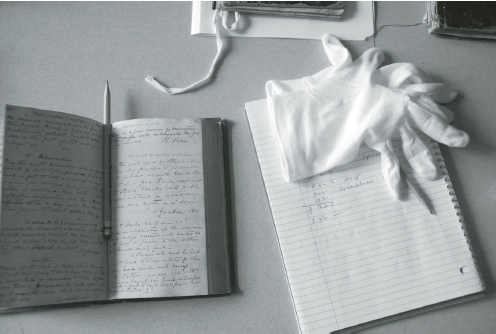

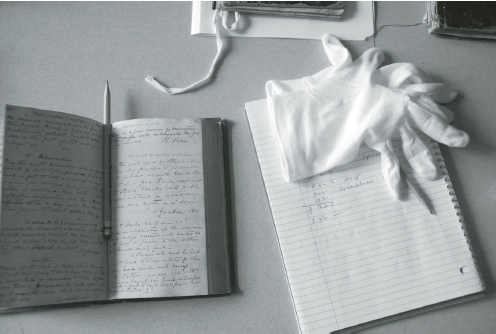

Working with Liberty Hall’s early-nineteenth-century manuscript cookbook. (John van Willigen)

Cookbooks as the Key to Kentucky Foodways

and Culinary History

Kentucky cookbooks (that is, collections of recipes produced by Kentucky authors or groups) provide a glimpse of what Kentuckians ate, how they prepared food, the cooking technology used, and the social setting of food preparation and consumption at the time of the book’s compilation. Tapping into this potential resource requires careful analytical reading, however. As John Egerton notes, “Cookbooks tend to keep their social and cultural clues discreetly buried between the lines, but when they can be uncovered they may be useful barometers of a society’s tastes and priorities and values” (1993, 17). This book is based on a close reading of a selection of Kentucky-published cookbooks from the past and the present.

It is clear that cookbooks and their recipes have changed considerably in terms of diversity and format. The first noticeable change is that the rate of publication has increased over time. There were few nineteenth- century cookbooks, although this started to change after the Civil War. During World War I, the Depression, and World War II, few cookbooks were produced. By the 1950s, there was a large increase in the number of cookbooks published, followed by another substantial surge starting in the 1980s. More recent increases reflect readers’ growing interest in food writing, which is associated with changes in the style and content of cookbooks. These changes are the result of many factors, including the development of new dishes, evolving recipe formats, new food preparation technology, shifting availability of ingredients, increased presence of branded or processed foods, growing interest in saving time when cooking, new knowledge about cooking techniques, greater cultural diversity in Kentucky communities, and changes in the meaning and politics of food.

Many of the changes in cookbooks and their recipes can best be understood in terms of the transformations occurring in the American food system. The two overarching changes are that consumers are less involved in producing food and that food must travel a longer distance. Using the idea of a watershed as a metaphor, culinary historian Ann Vileisis (2008) speaks of the “foodshed,” or the area from which we obtain our food. In the 175 years covered by this book, the limits of the foodshed have changed for many Kentuckians—from the garden spot near the house, adjacent fields and pastures, and the cellar to faraway and largely unknown locations. This has had important consequences. People now have less knowledge about where their food comes from, how it is produced, who the producers are, and whether it is wholesome and safe to eat. A major part of our culture has been taken from us. One of the consequences is a loss of knowledge and skill. One might say that, in certain realms, we have been decultured. At the same time, we have obtained new food knowledge. I may not know how to slaughter and dress a chicken, but I have a working knowledge of nutrition and I can prepare a credible pad Thai. Some argue that our interest in cookbooks is related to our separation from food production.

It is not often a cookbook’s goal to depict or explain history, but in the process of providing lists of ingredients and instructions for cooking them, it may reveal traces of history. Further, it is interesting to place cookbooks in their social context and to think about how they reflect their times. Often this is quite obvious in the recipes, but it may require a careful reading, rereading, and interpretation. When I originally conceived of this book, I thought in terms of excavating an archaeological site. Cook-books are like archaeological strata. Each one reflects something of the era in which it was created. It does not provide a complete picture of what life was like; rather, it offers a complex and hard-to-fathom tracing of reality as it existed for its creator. When archaeologists excavate a site, they may not find much to work with, and they are often hard-pressed to understand the meaning of the artifacts they do uncover. So it is with cookbooks: although much can be learned through the study of cookbooks and their recipes, they are of limited use for understanding foodways.

Working with Liberty Hall’s early-nineteenth-century manuscript cookbook. (John van Willigen)

One limitation is the problem of historical lag. With regard to using cookbooks and recipes to study culinary history, Karen Hess notes, “The lag between practice and the printed word is one of the most frustrating aspects of work in the discipline of culinary history” (Hess 1992, 44). Hess goes on to cite the example of johnnycake and other corn-based, hearth-baked breads of the early colonial era, noting that 175 years elapsed between the earliest preparation of these foods by American cooks and the recipes’ appearance in the historical record. This is not to say that these recipes did not exist, but they were most likely kept in people’s heads or sometimes written out by hand. In fact, most recipes are not written; they are stored deep in memory or improvised, based on the cook’s creative vision and knowledge of the fundamentals of cooking, as well as what is in the pantry. A lot of cooking is “done by ear,” to use Marion Flexner’s phrase describing the method of the African American cooks who worked for her family (Flexner 1941, x). Those wonderful cooks internalized the principles of preparation that produced the results they were interested in. So while there might be a recipe, it is probably not written down and perhaps not even memorized: it just is.

Even written recipes were rarely published in cookbooks, as it was common for families to keep their own handwritten books of recipes. Reliance on these manuscript cookbooks was very common. As Mary Tolford Wilson notes in reference to the early American colonial era, “Unless she was illiterate or unusually shiftless, the homemaker of course had her own written collection of receipts, medicinal as well as culinary, gathered from family and friends” (1984, viii). While reviewing the cookbook collection at Frankfort’s Liberty Hall, a historically important home built in 1796, I found a number of manuscript cookbooks. The oldest recipes were dated 1812, and it was obvious that others had been added through the years, many of them copied from other publications. Along with the recipes, there were many other kinds of notes, as well as an effort to index the materials. These early manuscript cookbooks were often passed from mother to daughter. In one case, culinary historian Karen Hess compiled a manuscript cookbook of Martha Washington’s (Hess 1981) and later released it as Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery and Booke of Sweet-meats (Hess 1996), with the addition of extensive historical annotations. In a case closer to home, the family that occupied the historic Riverside farm passed down a collection of recipes dating from about 1890 and written on a simple notepad. Riverside, which was built in the nineteenth century on the Ohio River in southwestern Jefferson County, is now part of metropolitan Louisville’s park system. The Riverside recipes are believed to come from Nannie Storts Moremen, who, along with Israel Putnam Moremen, owned the farm. Some of these recipes are included in a booklet titled Riverside Receipts (Linn and Neary 1999), published as part of the interpretive program at Riverside. Following is Riverside’s recipe for rice pudding.1

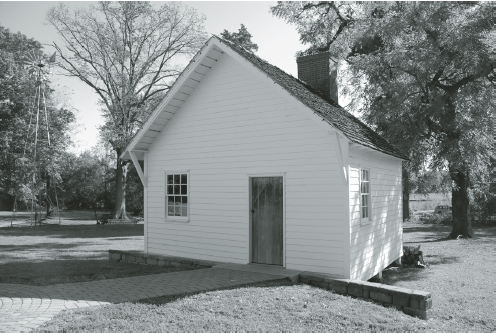

The restored kitchen at Riverside Historic Site in Jefferson County. (John van Willigen)

Grandma’s Pudding (1890)

Bake in a yellow earthen dish with not-too-hot-a-fire. Into the baker put a quart of new milk, a scant cupful of rice, two tablespoonfuls of sugar, a quarter of a teaspoonful of salt, half a cupful of large Eayes (brand name) raisins. After stirring well to dissolve the sugar, she grated some nutmeg on top. When a scum began to form upon the milk, she skimmed it in, and as fast as it formed, did so again. She did not let it brown until the rice began to thicken; then she let it brown on top. About an hour and a half was allowed for it to cook. When she lifted it from the oven and set it in the spring house to cool, it was delicious and seemed filled with cream. (Linn and Neary 1999, 19)

This recipe reveals some of the food preparation technology of the time. Note that it calls for “new milk.” About twelve to twenty-four hours after a cow is milked, the liquid separates into cream and milk. New milk refers to the liquid before that separation occurs; thus, new milk has a high butterfat content. (Today, homogenization breaks down the fat globules, which eliminates the butterfat’s separation from the rest of the milk.) Morning milk probably has the same meaning as new milk. In addition, the recipe gives no indication of the oven temperature, as the wood-burning ovens of the era did not have thermostats. Finally, the reference to a springhouse indicates that containers of milk were placed in springwater to keep them cool.

Many of Kentucky’s history archives have manuscript cookbooks from different periods. For instance, University of Kentucky archivist Deirdre A. Scaggs and Andrew W. McGraw wrote The Historic Kentucky Kitchen: Traditional Recipes for Today’s Cook (2013), based on manuscript cookbooks in the university’s special collections. Besides creating manuscript cookbooks, cooks often added their own recipes to printed cookbooks, old and new. It is typical to find recipes written down or pasted into antique and vintage cookbooks. Cookbooks served as little box files for recipes.

Manuscript recipes allowed sharing among friends and neighbors.2 Years ago, swapping recipes was something like friending someone on Facebook. Sharing recipes linked people together, created common memories, and provided an affiliation. On top of this, it was useful for cooking. This worked in both social time and social space. One intriguing question is how people decided which recipes to share. A quick review of community cookbooks shows that people tended to contribute recipes from loved ones, famous food writers or other celebrities, or famous restaurants: think Mom’s stack cake, Cissy Gregg’s dumplings, or the Beaumont Inn’s corn pudding.

Another limitation of using cookbooks to understand culinary history is that these books can have very long lives. For one thing, some of the better-known “national” cookbooks stay in print for many years, although they may exist in various editions. Related to this is that families often retain and use cookbooks over a long period. I bought a copy of the 1888 edition of Housekeeping in the Blue Grass a few years ago, and inside I found recipes from 1945 and 1962 that had been clipped from the newspaper. There was also a bill of sale for $1.60 for the cookbook dated February 1943 from W. K. Stewart Company in Louisville.

Cookbooks and recipes also vary in terms of the “taste” reference group they are written for. Recipes and their ingredients contain “prestige markers”: some cookbook writers serve as arbiters of what is considered “good taste,” and others make a point of selecting the everyday. Whether a recipe calls for Velveeta pasteurized processed cheese or Kenney’s artisanal aged Cheddar says something about the recipe writer’s position in the hierarchy of taste and perhaps his or her ideology of food. These meanings change over time. What was either high or low prestige at some point in the past can have a different meaning years later. Changes in the status of biscuits and cornbread are good examples. Another case of food being a marker of prestige is the iconic Kentucky dish called the Hot Brown sandwich. Fred K. Schmidt, a chef at the Brown Hotel, developed the recipe in 1926 and served it to the hotel’s late-night dinner-dance clientele as an alternative to ham and eggs. The current Brown Hotel recipe specifies Pecorino Romano cheese in a white sauce made with heavy cream, yet one can find recipes in community cookbooks based on Velveeta or generic cheese. Basically, the Hot Brown is an open-faced sandwich of sliced turkey on toast, covered with a Mornay sauce and crossed strips of bacon, and garnished with sliced tomatoes.

It is also possible to use the prestige of both recipes and ingredients ironically. What comes to mind are recipes for tiramisu that use Twinkies and Cool Whip rather than ladyfingers and mascarpone, or even dump cake or pig pickin’ cake recipes. This means that recipes and cookbooks can vary in terms of how they function as prestige markers and the extent to which they deploy irony.

The relationship between cookbooks and foodways is anything but direct. The recipes selected for inclusion in a cookbook do not necessarily represent what people really eat; the recipes may be incomplete depictions, one or two times removed from the carefully prepared dishes actually served at the table. In a similar vein, while it is safe to say that everybody eats, not everybody cooks, and very few people write cookbooks or even recipes for that matter. Cookbooks are a distillation of what those writers know about cooking and nutrition and what they think is important. Beyond this, their understanding of the audience’s knowledge of cooking is critical. Often, but not always, early published recipes included little information about procedure. This is usually seen as evidence that the cookbook users already knew the process, so it was not necessary to repeat it. More recently published recipes tend to include far more procedural instructions.

One interesting aspect that is often not reported in cookbooks is the source of a recipe. And when a source is described, it is often done inconsistently. In the case of The Kentucky Housewife, the earliest published Kentucky cookbook, the author cites the source of only one recipe out of about 1,300. In contrast, in most community cookbooks the recipes are signed, and a few are also attributed to other individuals. For instance, Heritage Cooking Crittenden County, 1792–1992 includes “Mamaw Duncan’s Chicken Casserole,” a recipe contributed by Marcia Lewis of Sturgis, the daughter-in-law of Helen Lewis, who was probably a member of one of the homemaker clubs that put the cookbook together. Even when there is some documentation of the source, the recipe’s historical roots largely disappear. There seems to be a much greater tendency to list the source if the contributor was famous or a beloved relative. The contribution and inclusion of a recipe may be motivated by the desire to commemorate a particular person. Much of the rich narrative of Ronni Lundy’s cookbooks, such as her Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes, and Honest Fried Chicken: The Heart and Soul of Southern Country Kitchens (1991), consists of stories of the people—often famous musicians—who devised the recipes. Fame also played a role in determining which recipes to include in What’s Cooking in Frankfort, produced by the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1949. It starts with recipes “used by wives of our Governors.” As the author states, “Our present beloved First Lady has kindly contributed one of Governor [Earle C.] Clements’ favorites,” reproduced below (Sutterlin 1949, 4).

Butterscotch Fudge Bars (1949)

½ cup butter

2 cups brown sugar (light)

2 eggs

2 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

½ teaspoon salt 1 teaspoon vanilla

1 cup nuts

Cream butter, gradually add sugar. Beat in eggs. Add dry ingredients, nuts and flavoring. Spread in well oiled pans. Bake 20 to 25 minutes at 375 degrees.

Clements was governor of Kentucky from 1947 to 1951.

As mentioned earlier, one theme developed in this book is that recipe format, precision in measurement, extent of culinary disclosure, and amount of contextualizing narrative have all changed over time. Changes in content and formatting began even earlier than the time frame considered here. For example, today we expect ingredients to be presented in the order of their use and in specific measured amounts. But according to food writer M. F. K. Fisher (1968, 6), this did not occur in cookbooks until the early nineteenth century. She notes that the first user of this innovation was William Kitchiner in The Cook’s Oracle, originally published in England and appearing in an American edition in 1830. Most editions of this book include a statement on the title page that “the quantity of each article is accurately stated by weight and measure; being the result of actual experiment,” reflecting the novelty of this innovation (Kitchiner 1830, i).

Another theme discussed at various points herein is that the cookbook enterprise has always been structured by gender. Cookbook writing has largely been the domain of women. In addition to the domestic sphere of child rearing and homemaking, the process of writing and compiling cookbooks was one area in which women were allowed to function more or less untrammeled, as evidenced by culinary history scholarship. The exhibit “The Old Girl Network: Charity Cookbooks and the Empowerment of Women,” presented at the University of Michigan’s Clements Library in 2008, is one example. Curated by eminent American culinary historian Janice Longone, the exhibit made it clear that involvement in the production of charity cookbooks allowed women to write, organize, market, and, above all, be in charge. Longone points out that the skills learned in the charity cookbook enterprise gave women a foundation to expand their realm beyond the domestic. The same can be said for the production of for-profit cookbooks.

Therefore, there are a limited number of Kentucky cookbooks written by men. According to my research, the first Kentucky cookbook written by a man was Tandy Ellis’s little pamphlet titled Camp Cooking, published in 1923 (an interesting little book that is discussed in more detail later). The most famous male-written cookbooks are those produced by Duncan Hines of Bowling Green, starting in 1939. Like Hines, most male cookbook authors are celebrities, professional chefs, or entrepreneurs. Men contributed a few recipes to some community cookbooks— most often, recipes for game.

In addition to gender, social class and ethnicity are important factors in cookbook production. In the earliest periods, most cookbooks were written by upper-middle-class white women or compiled by groups of upper-middle-class white women associated with mainline Protestant churches in towns or cities. Thus, the considerable role of African Americans in the development of Kentucky foodways was hidden behind the white women who hired or, prior to emancipation, owned them. For the most part, these African American cooks were unnamed, although there seem to be a few signed recipes by African Americans that appeared in cookbooks as early as 1894. The earliest Kentucky cookbook authored by an African American was Atholene Peyton’s The Peytonia Cook Book, published in 1906 in Louisville. Later in the twentieth century some African American women published their recipes through the agency of white women, and I found a few community cookbooks produced by African Americans. Therefore, our understanding of Kentucky foodways through cookbooks is influenced by the fact that cookbook production has always had a clear gender, class, and ethnic tendency.

Another part of the story is the contribution of Native Americans to Kentucky culinary history and their influence on Kentucky foodways. Although there were many Native American recipes, there were no early Native American cookbooks. The first European American pioneers in Kentucky ate a diet based on foods that were also important to the region’s Native Americans. Both groups grew similar crops, and the pioneer farmers made use of Native American farming practices, such as the companion planting of corn, beans, and squash. Pole beans would climb up the cornstalks, while the squash plants shaded the base of the corn plants, preventing the growth of weeds. The beans also improved soil fertility through nitrogen fixation. As a result of this practice, today you can buy what are called cornfield beans in many farmers’ markets across the state. The early European American farmers planted these crops in hills rather than rows—another Native American practice. And initially, both groups farmed based on hoe rather than plow cultivation. It is important to note that both exploited a wide variety of each of the three basic crops produced. Like the Native Americans, European Americans mastered the method of processing corn in alkali to produce hominy. Both were also hunters, which resulted in the addition of deer, bear, squirrel, rabbit, turkey, and waterfowl to their diet. Needless to say, both were subsistence farmers, using the food they produced for family consumption, not for the market.

There are many recipes of Native American origin in early cookbooks. These foods were especially important in the South and, along with foods of African origin, are one of the foundations of southern cuisine. Corn was the most important Native American food. Corn yields were much higher than wheat yields, and corn could be consumed in its milk phase as well as being processed as a mature grain. In addition, wheat required more careful soil preparation, and plantings in the rich, newly farmed Kentucky soil produced very leggy wheat stalks that would lodge or fall over. Early cookbooks often referred to cornmeal as Indian meal and included many different recipes for breads, ranging from hoecakes to light bread. Some cookbooks included recipes for roasting ears of corn, and early corn pudding recipes called for milk-stage field corn rather than today’s canned sweet corn.

One problem is that the culinary relationship between Native American and Euro-American Kentuckians is not well understood. Most casual accounts rely on legends about the Pilgrims of New England or the Pow-hatan peoples of Virginia rather than the actual culinary transactions occurring in the Bluegrass State. The exchange of foodways between Native Americans and the European colonists spanned about 200 years. It started far away from this region and continued in the contact sites of what would become Kentucky. Clearly, much of the influence was indirect, as there is archaeological evidence of European cultural influences far earlier than the appearance of the first Europeans in Kentucky.

Having a comprehensive list of Kentucky cookbooks was important for this project, although compiling such a list was challenging. It can never be complete: new cookbooks are always being written, many community cookbooks were printed in limited numbers and are difficult to find, and both old and new cookbooks are discovered all the time. The starting point for constructing the list was my own collection, which is continually growing with additions from used-book stores, library bookstores, antique stores, flea markets, and Ebay. This was supplemented by the list and description of cookbooks in John Egerton’s classic Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1993). Egerton, from Trigg County, includes a lot of Kentucky content in his writing about foods of the South, and he certainly represents a go-to source for southern and Kentucky food. I regard his list as a “hall of fame” of Kentucky cookbooks, although it does not include anything more recent than 1993. The search went well beyond this, as described in the introduction to the annotated bibliography.

To review: There are two basic types of Kentucky cookbooks. Most numerous are cookbooks that were compiled by church groups, home-maker associations, garden clubs, hospital auxiliaries, historical and ge-nealogical societies, service organizations, professional associations, volunteer fire departments, Junior Leagues, medical associations, parent- teacher associations, businesses, and other groups, usually to raise money for various projects and sometimes to increase awareness about a specific issue. Almost all the people involved in these projects were women. These are often called community cookbooks or sometimes charity cookbooks, and they account for the vast majority of the books on my list. The earliest community cookbook on the list is the classic Housekeeping in the Blue Grass, initially published in 1875 by the women’s group of the Presbyterian Church in Paris, Kentucky, and republished a number of times (see chapter 2). Generally, these types of cookbooks are not self-consciously focused on Kentucky food (though there are exceptions). That said, most community cookbooks contain the recipes that were on cooks’ minds and in their repertoires, so in this sense, they represent a regional cuisine. But it seems unlikely that the typical recipe contributor would ask herself whether her recipe represented the essence of the region’s foodways. There are many reasons why recipes are contributed, and expressing culinary heritage is just one of them. In some ways, random contributions may represent actual foodways better than recipes that are thought to reflect a region’s food traditions. Although one can discuss regional differences in food, there is considerable risk in mythologizing what people actually eat. There are subtle differences between what people really cook and eat and what people say about cooking and eating.

The second kind of cookbook, also important, is that written by food writers, chefs, restaurateurs, and celebrities with Kentucky ties. The earliest, published in 1839, is The Kentucky Housewife by Mrs. Lettice Bryan, who was born in Boyle County (see chapter 1). A few of these cookbooks were clearly intended as compilations of Kentucky foodways, such as Out of Kentucky Kitchens by Marion W. Flexner (1949), Charles Patteson’s Kentucky Cooking (1988), and Sharon Thompson’s Flavors of Kentucky (2006). Others are focused on the general category of southern foods rather than Kentucky foods. Examples of these are Camille Glenn’s The Heritage of Southern Cooking (1986) and Ronni Lundy’s Butter Beans to Blackberries: Recipes from the Southern Garden (1999). But both Glenn and Lundy have clear Kentucky ties: Glenn was raised in Dawson Springs in Hopkins County and worked in Louisville, and Lundy was raised in Louisville and spent significant time in Corbin in southeastern Kentucky.

A few cookbooks started as community cookbooks and evolved into the second type. The best example is Irene Hayes’s What’s Cooking in Kentucky (1965), which is still in print. This comprehensive cookbook was compiled to raise money for a church building fund in Hueysville in Floyd County and grew from there. A few cookbooks focus on Appalachia but have clear eastern Kentucky roots, including Sidney Saylor Farr’s More than Moonshine: Appalachian Recipes and Recollections (1983) and Mark F. Sohn’s Mountain Country Cooking: A Gathering of the Best Recipes from the Smokies to the Blue Ridge (1996). Other regional cookbooks focus on Louisville or the Bluegrass, and a few have a southern or western Kentucky orientation. Some cookbooks are linked to specific restaurants or chefs. Examples include Richard T. Hougen’s Look No Further: A Cookbook of Favorite Recipes from Boone Tavern Hotel, Berea College, Kentucky (1955) and the more recent Jonathan’s Bluegrass Table: Redefining Kentucky Cuisine (2009) by Jonathan Lundy, the owner-chef of his eponymous Lexington restaurant. Always interesting are celebrity cookbooks, which include The John Jacob Niles Cookbook (Rannells 1996), Naomi Judd’s Naomi’s Home Companion: A Treasury of Favorite Recipes, Food for Thought, and Kitchen Wit and Wisdom (1997), and Loretta Lynn’s You’re Cookin’ It Country: My Favorite Recipes and Memories (2004). There are also some “single-ingredient” cookbooks, including Elizabeth Ross’s Cornmeal Country: An American Tradition (2004) and Albert Schmid’s The Kentucky Bourbon Cookbook (2010).