RICHARD JANDA AND RICHARD LEHUN

1. INTRODUCTION

The project of constructing an economy that operates within the planet’s ecological boundaries is a matter of justice. Justice has to do with rendering what is due, and thus with a proper accounting for individual and collective conduct.1 Ethics has to do with good character and manners, and thus with proper behavior. Justice holds ethics to account. It is both a subset of ethics and the architecture of ethics. Thus, whereas one can discuss the ethical foundations of economics in general and of ecological economics in particular in the sense of seeking to identify forms of good behavior that would characterize the economy, the related justice inquiry sets the stage for identifying forms of governance, modes of accountability, and norms to discern fair shares of resources.

The existing economy is out of joint. Past and present generations have exploited resources and caused environmental and social externalities on a scale and at a pace that imperils the future prospects of life—human and nonhuman alike. To state this is to make a justice claim against the existing economy. It is also to contemplate a more just economy. Thus, any effort to build ecological economics requires an examination of the following questions: What justice is the existing economy purporting to render? What are the justice claims being made against the existing economy? And, what justice would be rendered by the ecological economy that would substitute for it?

1.1. The Illusory Search for a Unifying Ethic

These three questions immediately pose a difficult conceptual challenge for us. To approach them and to begin to make sense of them, a shift in expectations as to the kinds of answers we would hope and expect to find is also at stake. That is, we typically hope to find a basis for persuasion, so as to gain consent and adherence for the kind of answer being offered. Thus, in formulating answers to these questions, we are often seeking intuitions or evidence of the kinds of arguments that we believe are most likely to produce collective assent. If only the golden arguments could be found to which all would spontaneously adhere, we tell ourselves, we could be enabled simply to produce, in an act of collective will, a change from the existing economy to an ecological economy that would function within planetary boundaries. Thus, for example, we imagine that clear arguments can be made showing that the existing economy is focused too narrowly on the pursuit of consumption and growth, that this is unjust because it fails to take account of claims of nature against us, and that therefore adherence to a land ethic in which we view ourselves as stewards of nature could be made socially compelling. Sometimes, less ambitiously, we hope at least to discover the compelling arguments that some reasonable people could follow to guide their own choices when confronting a dystopic world. In this vein, we might hope to find guidance as to whether it is ethical to consume meat, own a car, live in the suburbs, or travel by plane.

Unfortunately, we will not get far looking for ideas about justice and ethics that could flow into public debate and produce collective, conscious, and reasoned assent. The very forum we would seek to persuade on the basis of individual choice and adherence is now utterly colonized by a conception of choice that elevates consumption and property to a right; thus, it resists inherently any appeal to make a choice that would circumscribe or scale back choices to consume or appropriate. Furthermore, the kinds of arguments we would employ in liberal ethics—be they consequentialist (looking to the outcomes of our acts) or deontological (looking to the responsibilities we have)—are viewed as simply existing on a menu of possible ethics to be selected by individuals. For example, it is standard in liberal ethics discourse to situate arguments within typologies such as act consequentialism, prioritarianism, Lockean libertarianism, rule consequentialism, capabilities, and pure deontology so as to discuss how different arguments can be made from these various standpoints within liberalism (e.g., see Schlosberg 2012). If one seeks then to produce an even broader moral overlapping consensus, to borrow a term from Rawls (1993), that could encompass not only versions of arguments from liberalism but also from outside liberalism (religious positions, Marxist positions grounded in radical social critique, deep ecologist positions grounded on a moral priority to nature, and so on), all that one ends up generating is yet another contribution to the marketplace of ideas, from which individuals will select their preferred position. The proposed solution—an argument that would generate consensus—becomes a further standpoint to take account of and to absorb in producing a consensus and therefore a further impediment to achieving it.

If what we faced was an unencumbered, boundless field of social endeavor in which the test of ideas could ultimately be whether they were freely chosen and retained, we could simply wait for the inherent appeal of arguments—their strength or weakness—to win the day. Even if we acknowledged, more realistically, that the inherent rationality of argument will not determine what in fact gains social consensus, we might nevertheless persist in setting out and defending the rational social ideal we envisage, and then seek to counter politically whatever forces we believe exist to impede the triumph of the right and the true.

1.2. The Question Put in This Chapter

These approaches are utterly inadequate to overcome the collective action problem we now face with respect to the biosphere, and arguably they have long since proven inadequate to confront the pathologies of collective action concerning the equitable distribution of social goods. What we face, in short, is a need for global coordination that will not be solved by seeking to find and develop a single set of ethical commitments to which everyone will adhere. We must pose our question in the following way: given deep ethical divergences, variable but persistent commitments to the protection of individual preferences to consume and appropriate, and the impossibility of gaining acceptance of a unified set of norms within the proximate time frame needed to produce collection action, what kind of legitimate justice foundations could be given to an ecological economy that would emerge from the existing economy?

Two preliminary objections to this question should be considered. A first, hard-line objection would challenge the question as irrelevant because it fails to envisage the possibility of overcoming ethical diversity through nondemocratic means. A second, soft-line objection would claim that the question is irrelevant because conventional liberal democratic justice theories are already flexible enough to absorb the vast array of existing social views; also, in any event, whatever is proposed as an answer to the question of ecological justice would have to survive democratic scrutiny. Before setting out the plan for this chapter, therefore, these two threshold objections will be canvased briefly in turn.

1.3. The Hard-Line Objection

According to the hard-line objection, if the production of democratic consensus around a common ecological framework is impossible, then undemocratic methods must ultimately be adopted to pursue it. The point is not to cope with the plurality of ethical positions but to overcome them. Hence, we should expect authoritarian solutions to our ecological crisis, perhaps (to use a current example) originating in China (Beeson 2010).2

In fact, there is no necessary connection between assuming, on the one hand, that it is impossible to produce a consensus upon a singular normative framework, and pursuing undemocratic methods as a result. It is only if we affirm that a singular ethic is required, despite the impossibility of achieving it, that we would seek recourse to authoritarian means. Furthermore, a deeper critique of authoritarianism reveals that it is incapable of producing a singular ethic and especially incapable—despite the myth of noblesse oblige—of producing coordinated stewardship of planetary systems. The corruption to which authoritarianism is inherently subject and the incentives that it faces to gain and concentrate wealth are far from providing any guarantee that its imposed ethic will respect planetary boundaries. On the other hand, because authoritarian regimes compose part of the global context of ethical pluralism, the justice frameworks and accountability standards needed to arrange a network that assures the provision and safeguard of environmental public goods will have to be operable also in such contexts.

1.4. The Soft-Line Objection

According to the soft-line objection, authoritarian, undemocratic means will not produce a legitimate ecological economy; therefore, we are left inevitably to rely upon democracy to produce whatever framework is proposed (Burnell 2009).3 In the end, despite protests to the contrary, the approach amounts to a version of the conventional effort to formulate an argument that will be subject to liberal democratic deliberation.

Stated in this way, the soft-line objection also proceeds on the assumption that we are aiming to produce a singular normative framework. The very thing democracy cannot achieve is purported to require democracy. If the objection is redirected to affirm simply that democracy is about producing legitimate outcomes from social pluralism, it fails to address a critical feature of our collective action context: there is no single democratic forum, and indeed no monopoly of democratic forms—let alone a common understanding of democracy—within which collective decisions about global collective action can be achieved.

Even if one were to grant that global democratic institutions could produce a global collective action framework (although this is dubious given the capture to which existing democratic institutions are prone), the soft-line objection would nevertheless dissolve. First, no such global institutions exist. In fact, we find ourselves within a governance context in which a network of multiple regimes must be steered and coordinated—not only those of nation-states but also those of corporations and other nonstate actors. Second, even if the international state system were viewed as our closest available substitute for global democratic institutions, it has so far proven incapable of producing the requisite level of coordination. This is not to say that the state system should be eliminated or bypassed—that too would be a naïve and insufficiently multidimensional analysis. Rather, it is to say that what we require is a way to model the coordination of multiple justice frameworks—and in particular, the deficiencies and inadequacies that will be produced in seeking to render multiple justice frameworks that are interlinked and in some measure interoperable—rather than a single theory of justice to which we would all hope to adhere.

1.5. The Need for a Metatheoretical Approach

The production of such a justice model is what is meant by a metatheoretical approach to justice. If our only hope to produce the requisite collective action proximately is to deploy a global social network for the coordination of behavior, and if by definition such a social network will have to operate across multiple ethical “platforms,” then a metatheoretical model for the operation of such a network is needed.

A metaphor to represent this is “swarm intelligence”: the collective behavior of self-organized systems—democratic or otherwise—that interact through common signaling functions. Swarms can behave like locusts to produce environmental devastation, or they can behave like bees and help to maintain and reproduce their ecosystems. The contribution of a metatheoretical justice model is to identify the deficiencies of existing signaling across multiple justice platforms, producing our locust-like behavior. The term “model” rather than “theory” is used because the goal of the analysis is not to offer another theory seeking adherence. Rather, it is to produce an aggregate, macroscopic assessment of the justice deficits currently being produced by the interacting signals of behavior in the existing economy. Metatheory is to theory as signaling is to behavior. Metatheory concerns the orientation of justice frameworks as they interact. The justice deficits of the price mechanism, which is the principal signaling we currently rely upon, thus becomes a starting point for the model. Identifying those deficits relates ultimately to identifying a more adequate signaling function, reflecting a gift relationship with nature and coordinating fiduciary roles.

1.6. Outline of the Argument

The metatheoretical standpoint inscribed in ecological economics is the starting point for this chapter.4 Having identified what the metatheoretical approach is, the chapter turns to an application of the metatheoretical model so as to assess the justice deficits of the existing economy. These considerations point us toward what shall be called a second Copernican revolution in the modeling of justice, a modeling that requires us to discover how to introduce a signaling function into the existing economy that will allow us to take up the role of stewards or fiduciaries of the entire oikos, not just gatherers and exploiters of available (and disappearing) low-entropy resources. The chapter then seeks to identify a fiduciary methodology consistent with the metatheoretical approach that could overcome the justice deficits of the existing economy, against the backdrop of what the existing economy leaves unaccounted. The chapter concludes by raising a justice claim against the fiduciary methodology we seek to develop: the transition from the existing economy to an ecological economy will itself present the dramatic challenge of shifting our own relationship to subjectivity and freedom.

2. A METATHEORETICAL APPROACH TO JUSTICE

To establish justice foundations for an ecological economy, we need a theory of theories of justice, rather than just another theory. This is because we need to align and interrelate our disparate norms of just behavior—those that now actually guide us—with what we can gather from science about our place in, disruption of, and steering capacity toward planetary systems and boundaries. The challenge of ecological economics is not one that can be borne simply by those who adhere to one particular model of justice. It must be borne by all. Any individual theory or model of justice will seek to organize and rank justice claims so as to produce the maximum social aggregate of justice. In the wake of accumulating justice deficits after two world wars and the Holocaust, post-Enlightenment (postmodern) conceptions of justice put into doubt whether any singular, totalizing theory of justice is possible (Horkheimer and Adorno 1982). Furthermore, we are confronted with the challenge of producing global collective action with respect to planetary systems out of overlapping and conflicting social affirmations of justice.

At the outset, a metatheoretical approach is to be distinguished from normative pluralism. Normative pluralism consists of identifying all the partial sets of justice conceptions, seeing them as operating in relation to each other, acknowledging that individuals negotiate their way among them, and adhering sometimes to multiple conceptions within the multiple normative orders in which they find themselves (Kleinhans and Macdonald 1997). Although this response can be a prolegomenon to setting justice foundations to ecological economics, it is in itself inadequate to the task. We are faced with overcoming the collective action problem posed by the aggregate impacts of our individual choices on the planet. Our plural conceptions of justice are not spontaneously aligning toward the reduction and elimination of those impacts. On the contrary, we lack a common set of signals for behavior about the value to be placed in collective goods. The pluralism of justice conceptions operating in conflict is in fact impeding the emergence of such signals.

Take the example of climate change and how the global economy should be oriented toward it. For those in developing countries, access to and deployment of the resources, technologies, and modes of production that developed countries have exploited is a matter of justice (Sen 2009). The gaping divide in standards of living between parts of the world, with attendant incapacity to provide for basic needs, produces overwhelming justice claims. Yet as China’s recent experience demonstrates, the path to development is marked by growth in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and environmental devastation. Developing countries claim that the burden of reducing these impacts should be most heavily borne by those who have most exploited resources over time: a climate debt is owed. Leading developed countries claim that those living in the present cannot be held to account for what was done by others in the past: no climate debt is owed (see Posner and Weisbach 2010). These are conflicting justice conceptions. Their coexistence in a pluralism of conceptions is a problem to be solved rather than a contribution, if you will, to the richness of social life.

A metatheoretical approach goes further than pluralism and seeks to identify the strengths and inadequacies of particular justice conceptions—what they reveal and what they conceal; what they enable and what they disable. In particular, a metatheoretical approach would hold to account the deployment of any justice conception in arriving at social outcomes by asking what injustices will thereby be done in addition to, or as the result of, implementing that particular form of justice.

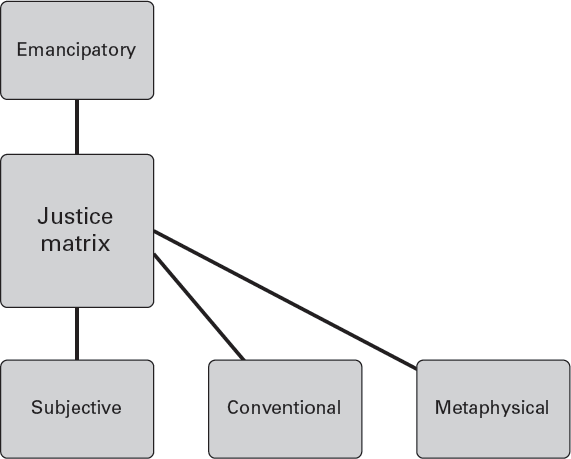

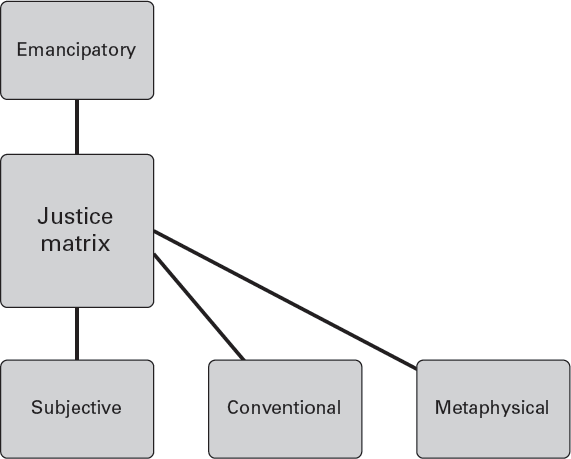

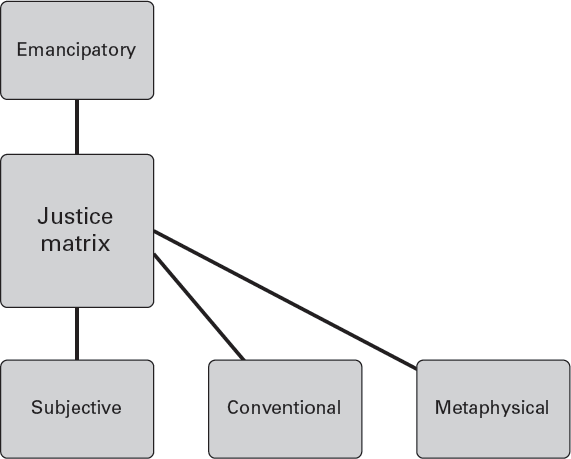

A metatheoretical approach can be modeled according to three dimensions of justice: (1) the metaphysical (that imbuing justice from without—originally the sacred), (2) the subjective (that ascribed to justice by our own lights), and (3) the conventional (that given to justice by society). A fourth dimension running through the other three—that of emancipatory justice—relates to enabling our freedom from any fixed justice constraint established in the other dimensions. Emancipatory claims emerge from the subjective dimension of justice. However, insofar as they are a negation of existing inadequate justice, they cannot simply be mapped within the three foregoing dimensions. They therefore add a fourth dimension running through and in tension with the other three (figure 3.1). Whereas metaphysical, subjective, and conventional claims map out “horizontally” the possible constitution of justice claims, the emancipatory dimension maps out “vertically” how we stand in relation to those constituted claims—either in making them so as to overcome justice burdens weighing upon us (the positive emancipatory claim) or in seeking to bear the weight of those burdens by submitting to them (the negative emancipatory claim).

Figure 3.1. Four dimensions of justice.

For example, we could take up a relationship of stewardship to the effects of our choices upon planetary boundaries through either a positive or negative emancipatory claim. The positive emancipatory claim would seek to free ourselves and future generations from the justice burden being imposed by our existing choices and to enable a social transformation to accomplish this. The negative emancipatory claim would seek to bring ourselves and future generations under the aegis of what is required of us by our relationship to what is other, namely the conditions of life, and to conform to those requirements.

Emancipatory claims have become central to contemporary justice models. They are notably embedded in both the position of developing countries and of leading developed countries just described. Both seek to maintain the greatest possible scope for overcoming limits upon our choices by insisting on the priority of economic development. Amartya Sen (1999) captured this notion in the phrase “development as freedom.”

We refer to the interplay and tension among all four dimensions through which specific justice claims are engendered as a “justice matrix.” A matrix shares with justice (the right) the quality of providing a structure, support, or architecture within which a claim can reside. Its purpose is to be able to map all possible sources of justice deficiency that can be articulated—as a claim—upon our collective efforts to render justice. Because the dimensions of justice in this matrix do not take their orientation from any substantive theory of justice but rather seek to locate how justice claims can arise, the test that must be put to them is whether they can provide a complete mapping. Because the dimensions include self-constituted, socially constituted, and supervening nonhuman claims—as well as the justice claims that arise out of the effort to break free from the constraints of any of the foregoing—they are designed axiomatically to map all possible claims.

A metatheoretical analysis cannot be used simply to restore a grand balance to justice by reasserting justice claims that have been cast aside and asserting a notional equality to all justice claims. That would be to shift from the effort to map and identify all possible claims to the effort to rank and order them—in short, constructing a new theory of justice. However, a metatheoretical analysis does reveal that the justice claims weighed by the existing economy align most with the subjective dimension of the justice matrix—that is, the marketplace or battleground of contested views. The next section turns to an immanent critique of how that arose.

3. THE JUSTICE CONSIDERATIONS UNACCOUNTED FOR IN THE EXISTING ECONOMY

As documented in chapter 2, it is not inherent to an economy that it functions according to transaction and market exchange. Yet the existing economy has taken on a self-reproducing and autonomous quality by purporting merely to channel the inherent characteristics of economic actors. It is in this sense that, within the justice matrix, it aligns most with subjective claims. Because economic actors are understood inherently to pursue self-interest and even make gifts to gain favor, the only kind of justice that can be rendered is one that the actors themselves would each affirm for themselves.5 No other justice claim is held to be realistic or socially reproducible. This is the world of transaction and contract. The economy thus comes to contain the aggregate of justice simply by definition because it aggregates all of the individual affirmations of outcomes sought in transactions and achieved in contracts. It achieves the justice of exchange.

The justice of exchange is perfected in two ideas: freedom and efficiency. All are free to pursue their own interests, and gains in efficiency are achieved as long as the self-interest of one is advanced without that of another being prejudiced. An efficient economy—one that succeeds in aggregating and aligning all individual self-interests (or at least notionally compensates for prejudice) is just because no other form of justice is possible, in the sense that no other form of justice coheres with real, existing subjectivity. Hegel’s dictum—that the rational is the actual and the actual is the rational—is transmuted into the following: justice is the actual outcome produced by self-interested rational actors. Indeed, a sign of the question-begging quality of the justice that is affirmed for the existing economy qua aggregator of individual self-interest is that justice drops out of the equation. The idea of justice really adds nothing to the simpler formula: self-interested rational actors produce the actual outcome of the economy. Its justice is efficiency. It is thus an important feature of the existing economy as an autonomous social field that it succeeds in occluding its own justice affirmations. The dictum becomes “justice is what justice is,” which is another way of saying that justice considerations are irrelevant and give way to brute facts. An increase in the aggregate of justice becomes simply having more of what the economy already is: growth of the economy, which is called a gain in welfare. The single metric for justice is efficiency and the increase of its aggregate is growth.

It has been commonplace since Aristotle, however, that the justice of exchange is separable from the justice of distribution. The binary corrective justice achieved between parties to a transaction will not incrementally and spontaneously aggregate into the geometric proportions of distributive justice. Corrective justice can coexist with distributive injustice but will not necessarily do so. Thus, an economy that narrows its justice considerations to the outcomes produced by the binary affirmations of individual actors in transactions will not have any clear footing in distributive justice. Indeed, in this respect, the economic sphere has come to be separable from the social sphere. Political investment is made in the social sphere so as to produce a modicum of distributive justice modulating the outcomes of the economy. However, the economic sphere has priority over the social sphere in the sense that the efficient outcomes of the economy are taken as given and are only to be adjusted by social regulation to produce greater equity, understood as fairness.

The traditional Aristotelian categories of justice—corrective justice, distributive justice, and equity—can be characterized within the dimensions of the justice matrix. Each of the Aristotelian categories participates in each of the dimensions, although equity tends to concentrate in the metaphysical, corrective justice in the subjective, and distributive justice in the conventional. Aristotle conceived of the two domains of corrective and distributive justice as themselves leaving unfulfilled the entire conceptual space of justice: thus, the notion of equity (epikeia) had to be added to the other two as a general adjustment for the inadequacy of the justice that would be produced, in aggregate, through the pursuit of norms of corrective and distributive justice. However, the justice rendered by the existing economy serves to narrow the constellation of possible justice considerations by reducing its justice to efficiency (a version of corrective justice, especially given the Pareto principle) and reserving the rest of justice to “equity”—that is, giving priority to the former over the latter. In effect, equity becomes collapsed with distributive justice. Any supervening, metaphysical conception is emptied out, largely because it becomes identified with mythology and unreason (see Horkheimer and Adorno 1982). Any notion that justice is owed to what has been given to us (in the “given” that is the earth) is relegated to private faith. Aristotle’s three-dimensional justice becomes a flattened two-dimensional justice. In short, the justice conception operating within the existing economy narrows and occludes the constellation of possible justice outcomes.

Viewed within the justice matrix, the contemporary market economy relies upon a conception of justice that reduces “equity” to the production of conventions of distribution (equity) and subjective (efficiency) dimensions. A metatheoretical approach, by situating justice claims in relation to a matrix of possible claims, helps to give an account of what is left out of any specific set of claims: that is, any strong relationship to supervening metaphysical claims.6 In particular, it helps to reveal that the metaphysical claims against which subjective claims have emerged in tension and from which they have sought emancipation are occluded—flattened—by our current configuration of the justice matrix. This insight had already been suggested in chapter 1, which showed how alternative conceptions of the economy tend to give precedence to justice claims arising outside of ourselves—from God, nature, or our place in the whole.

In a flattened configuration of the justice matrix, the metaphysical justice claims not made out within the subjective and conventional dimensions remain present but repressed. They are aggregated within other sets of claims and in some measure orient them, but are not themselves signaled. For example, those who would seek to repair or restore the earth out of a sense that past and future generations have claims upon us will tend to articulate these claims as best they can within the language of distribution or efficiency. Thus, sustainable development claims are often made out to involve fair distribution of access to the resources needed for development, and the proposed tools to accomplish this are often markets for the purchase and sale of property rights in the environmental damage being done. It is very difficult, within justice conceptions associated with what can best be called modernity, to articulate claims made directly on behalf of the earth.

Against this backdrop, one task for ecological economics becomes to elaborate what an economy operating on a more fully differentiated justice conception would look like. The term “ecological economics” is promising for this task, but it often fails to go in that direction, particularly when it restricts itself, like “environmental economics” to finding ways to internalize externalities generated by the economy back within the economy. The attempt to internalize externalities flows logically from the attempt to resolve self-defeating justice claims made for the existing economy (i.e., immanent critique): if the existing economy is meant to produce efficiency but does not do so because it undersupplies the public goods (ecosystem services) necessary for the functioning of the economy, there is a “market failure” internal to the economy. Such a result is a kind of paradox, of course, because it amounts to saying that the entire market is failing to be a market.

If a more fully differentiated justice conception is not sought, a solution may be to make the market behave like a market by putting a price on “ecosystem services,” thereby preserving the efficiency logic of the existing economy but correcting its market failure. Price remains the one signal that is relied upon to coordinate the multitude of preferences and ethical investments in the environment or any other social good because it is taken to be a universal and interoperable measure of choices and value—however incommensurable. Internalizing externalities does not in itself raise a fundamental justice critique; it simply holds the economy to its own standard and does not challenge the monopoly of the price function on the signaling of activity in the economy.

The beginning point in immanent critique is nevertheless promising for deepening the justice considerations at stake in the economy. The failure of the economy to perform as an economy on its own terms (market failures), despite the fact that it purports to be a self-reproducing aggregation of efficient (just) outcomes, raises the possibility that there is a set of justice considerations unaccounted for in the existing economy and signals of justice claims that are muted or nonexistent. This prompts a reconsideration of the term “ecological economics” as going beyond market correction, and this is the standpoint we take in this book.

4. OVERSTEPPING PLANETARY BOUNDARIES: TOWARD A SECOND COPERNICAN REVOLUTION IN JUSTICE THEORY

The contemporary configuration of the justice matrix, with the priority it gives to subjective claims and its flattening out of metaphysical claims, can be traced to the Enlightenment (see Horkheimer and Adorno 1982). The first “Copernican Revolution” of justice theory, developed by Kant, placed man at the center and measure of all things by identifying the human subject as determining the grounds of knowledge, and human agency as determining the contours of justice (Kant 2003). Unlike the Copernican Revolution in science, which reoriented us toward our place in the cosmos, the revolution in justice theory oriented us away from our place in the cosmos. In this regard, the Enlightenment project became one of overcoming any artificial and archaic limits upon knowledge: only those limits to knowledge that were inherent to the human subject itself were to be accepted, and even those were contestable. Human subjectivity as the ground of knowledge, and human agency as the measure of justice, were combined into an equation articulated by Spinoza and rearticulated repeatedly since: knowledge is power. The mythologized mysteries of nature were to be revealed as scientific laws, and the subservience to fate and authority was to be overcome. Free inquiry and free choice were the watchwords of the Enlightenment. Emancipation was its theme. The free market was its progeny.

The goal of justice theory became to throw off the shackles of repressed self-determination and to model the enabling of emancipation. There are two main contemporary models of that sort. The dominant liberal model is about enabling the freedom to exploit, produce from, appropriate, and consume resources. Justice is achieved as long as whatever interferes with that freedom is held to account using the counterweight of discipline, power, and authority, notably as deployed by the state in protecting rights. The other, discredited socialist countermodel is about emancipating us from exploitation, private control of production, disproportionate appropriation, and overconsumption by some so that the means of production can be controlled and shared by all. Justice is achieved when discipline, power, and authority are brought to bear, for redistributive purposes, on the past outcomes of the liberal model. Both models seek to harness human mastery over nature so as to maximize the sphere of enabled agency.

One can state two truisms in this regard. The dominant liberal model invests most justice resources in the emancipation of individual agency. The countermodel invests most justice resources in the emancipation of collective agency. They are dialectically intertwined. The dominant model postulates a justice dividend of enhanced and enabled collective agency if individual agency is emancipated. The countermodel postulates an enhanced and enabled individual agency if collective agency is emancipated. Both are premised on the inadequacy of the countermodel, and neither is designed to confront the inadequacy of emancipation itself. Neither attempts to model the disabling that is produced through what is emancipated. Both simply pass that disabling on as an externality for succeeding generations.

Now, we confront the fact that our centuries-long emancipatory quest has succeeded in producing a form of human mastery over nature. Indeed, Žižek has argued that we have eradicated nature as a category because at least the biosphere can no longer be viewed as a causal sphere distinct from human agency (Žižek 2008:433–443). However, this mastery is impotent to address its own self-destructive capacity. Our emancipated science allows us to determine that we have overstepped the planetary boundaries requisite for the survival and flourishing of life, but nevertheless our emancipated agency surges onward, increasing the very exploitation and consumption that produces this outcome.

What is revealed about the justice foundation of our current economy that it has been constructed so as to overstep planetary boundaries? Nothing less than that a second Copernican Revolution in our modeling of justice is required. A second Copernican Revolution in justice theory would again reorient us toward the relationship between our subjectivity and justice, but now with our subjectivity as the source of the injustice to be overcome. Like Copernicus’ own revolution, it would decenter us—and place us back into a cosmic narrative from which the Enlightenment wrenched us. What justice theory would now model is how to rectify injustices done in the pursuit of emancipated economic agency. It would recognize that the celebration of freedom by the economic agent, when it operates at the present scale, enslaves the other both now and in the future by altering the biogeochemical processes of life. In particular, the scale of time over which the externalized burden of our emancipation accumulates is longer than a human lifetime. For the human agent making choices now, the injustice of that emancipated agency appears ghost-like or spectral (Derrida 1994). It is a shadow of the past and a legacy to haunt the future, but it is not recognized to be a living presence now. Yet it is precisely if that injustice is allowed to remain merely spectral that it can eventually erupt into the present as an overwhelming and insurmountable burden. Is it not remarkable to realize that fossil fuels are the freed and burnt ghosts of dead creatures from long ago?

The second Copernican Revolution in modeling justice is arguably already under way as the narratives of cosmic and biological evolution profoundly change our understanding of what it means to be human (see Chaisson 2006; Wilson 2004). We are now seeking to recapture ancient wisdoms that understood human embeddedness. In this volume, Timmerman recovers justice conceptions that were delegitimated as emancipation gained preeminence. Yet it would be paradoxical and ultimately unsuccessful to deny the Enlightenment legacy in an effort to overcome the legacy of the Enlightenment. As we identify the justice deficit of the contemporary economy, we are not only continuing to live with the legacy of the Enlightenment that will be left for generations, but we are also applying the knowledge drawn from what the Enlightenment made possible. That legacy is not one of a particular continent or culture, but it is now borne and shared by all of life.

Thus, the second Copernican Revolution is not so much a substitution for the first as it is a repositioning of it. If the metaphor may be pursued, whereas Copernicus shifted perspective as to what lay at the center of our own solar system and empowered us to see better where we stand in relation to the universe around us, subsequent learning, building on Copernicus, has repositioned the significance and centrality of our own solar system in relation to the constellations (billions of galaxies) around us. A second Copernican Revolution in modeling justice also would reposition the centrality of our own pursuit of freedom in relation to a wider constellation of justice considerations (the justice matrix), which bear upon both our stewardship of the conditions for the possibility of life itself and the incontrovertible contemporary reality that each of our free choices impinges upon every other being.

These last affirmations deserve additional context. When the Enlightenment project took hold, the environment in which our freedom was to be exercised seemed inconceivably vast and capable of absorbing indefinitely any human intervention. Furthermore, it appeared plausible to imagine that there was a sphere of individual autonomy in which one’s own choices could be held discrete from effects on others—so much so that the formula “my freedom ends where yours begins” did not seem to beg a question, namely whether there was any point at which my freedom can be disassociated from yours. Common examples to illustrate that the formula made sense included that certain economic preferences of mine—to purchase or consume a widget—had no bearing on your freedom and thus give rise to a protected sphere of right.

It is true that, at least by the time of Malthus in the eighteenth century, human agency generating environmental catastrophe had crept into the ethos of Enlightenment thought. Thus, the capacity of the environment to absorb human action began to take on perceived but, it seemed, distant limits. Similarly, the externalities generated for others by individual choices came more and more sharply into view as “market failures.” These were nevertheless treated as exceptions to the general principle that discrete choices could be assembled into free transactions that contained the meeting of the minds—the idea of an efficient contract. However, Malthusian warnings and incremental efforts to regulate externalities have ceded now to a starker and more radical post-Enlightenment ethos. Human action not only affects the environment, it now has responsibility for it. Externalities are not exceptions to free transactions; they arise from all transactions. This was not always so. It is the result of the Faustian bargain we have struck, perhaps unwittingly, to gain mastery of nature.

There is thus a deep justice deficit in the operation of the existing economy. What is being held to account as the singular justice metric is the capacity for free choice. How the exercise of free choice disables future generations and encroaches upon a safe operating space for life is not held to account. One prerequisite for shifting from the existing economy to an ecological economy would be to provide an accounting for the injustice we do in exercising free choice. This would require, in particular, that we be signaled in our transactions, not only as to the resources we will have to provide so as to allow our choice (price), but also as to the resources we will have to forgo so as to respect planetary boundaries and as to the resources we will have to invest to restore what we are in the midst of damaging. Each transaction would have to carry with it not only a price signal but also signal as to its environmental and social cost.

Consistent with the metatheoretical approach described previously, we should resist the temptation to erect for ecological economics a new singular theory of justice to replace the myriad efforts to establish a theory of justice underpinning a market economy functioning within liberal democratic institutions. Indeed, if respect for planetary boundaries were to be consecrated as the new grounding principle to replace freedom or emancipation, this too could and indeed would work injustice. There is a particular form of blindness that can come with rendering justice purely out of fear of destruction. Everything else can fade from view. Anything might be done in the name of holding off apocalypse. We can escape from this paradox, not by escaping the laws of the universe—from which there is no escape—but by enabling a repositioning of human agency, to use Bruce Jennings’ term, as relational and embedded. This cannot be achieved simply by having us all adopt such a position—which we will not do—but rather by enabling and reinforcing signals of behavior that will move us in this direction. A justice model for ecological economics would seek to hold the economy to account for producing outcomes consistent with planetary boundaries, but it would also hold it to account for having to address other legitimate claims, including those arising from human agency and intersubjective needs and relations.

Furthermore, a justice model for ecological economics will be centrally focused upon holding the economy to account in its transition to an ecological economy. This means accounting for the burden of accumulated debt from the existing transgression of planetary boundaries, such as the enormous carbon debt owed by the industrialized countries for filling the earth’s carbon sinks to overflowing. The just way to manage and discharge that debt as well as to address the accumulation of new debt becomes a central governance concern for ecological economics. It also means accounting for the way our modes of governance will address the resistance of existing economic actors to any transition. It means finally accounting for the inevitable deficit that will arise—and is already arising—from the gap between what we imagine an ecological economy might be and what it actually will produce.

The transition to an ecological economy will require new kinds of economic actors, heightened signaling capacity to steer multiple indicators of just economic outcomes, and a highly differentiated model of fair shares of planetary resources. The forms of stewardship this entails suggests that a fiduciary concept focused on these requisite forms of economic capacity will lie at the center of the justice model. This fiduciary concept will have to bear the burden of accounting for and rendering justice to the incommensurable claims made upon the economy. Not only can the avoidance of one planetary boundary encroach upon another, but the avoidance of planetary boundaries will encroach upon other deeply held justice claims, such as the claim that all have a right to gain their highest possible remuneration.

5. HOW IS THE SHIFT FROM MARKET ECONOMICS TO ECOLOGICAL ECONOMICS A SHIFT FROM THEORY TO METATHEORY?

A capitalist market economy that seeks growth is tied to the liberal justice model that focuses on the emancipation of individual agency. It leaves out of account our stewardship of the environment and the economy’s systemic creation of externalities. The socialist justice model, although it reverses the locus of emancipation, is nevertheless tied to the same process of mastery of nature. The contemporary confluence of capitalism and socialism in a global economy—not only in China but in Brazil, India, and Russia—signals that the older ideological locus of justice antinomies has lost its force (Hardt and Negri 2000). With the fall of communism, the justice matrix shifted its axis away from the antinomies of individual and collective emancipation toward the antinomies of positive (self-affirming) and negative (other-regarding) emancipation. Capitalism globalized, but it was not the end of history as Fukuyama (2011) would have it. The putative triumph of individual (bourgeois) emancipation over collective emancipation revealed with even greater stringency the deficit of other-regarding, self-denying, negative emancipatory claims confronting the legacy of self-affirming bourgeois freedom.

Ecological economics is something other than capitalism or socialism. It is an attempt to bring to bear what we know and do not know of the household we manage—now our whole environment (oikos-logos)—on the norms governing our free choices (oikos-nomos). We seek to steer those free choices according to the contours of scientific knowledge and uncertainty concerning the effects we produce on life and its prospects. The effort to place economy within ecology is metatheoretical, not simply in the sense that it is transdisciplinary (linking social and natural sciences). In a more radical sense, it requires theorizing how bodies of thought can be made to interact and interoperate.7

An illustration may help to explain the foregoing. Suppose that an oil company executive explains that the problem of crossing planetary boundaries for atmospheric CO2 and other GHGs, as important and legitimate as it is to address, must simply give way to the economic reality. Given increasing energy demand and the slow pace at which renewables are coming on stream, we will have increasing global fossil fuel consumption over the next fifty years. In response, a climate scientist responds that, as important and legitimate as it is to consider how to address increasing energy demand, we cannot allow increasing fossil fuel consumption over the next fifty years if we are to stabilize GHGs at acceptable levels. As it stands, these two discourses are superimposed upon each other, and the market discourse trumps by default. Ecological economics seeks to bring these two discourses together and to establish principles of justice. According to these principles, the scientific discourse could gain capacity not only to trump the market discourse, but also to take account of what is lost when one discourse trumps the other.

How does this debate look from a metatheoretical perspective? The justice claims made by the executive are situated principally within the subjective dimension (efficiency imperative), with some reliance on the conventional (freedom of contract) and implicit reference to the emancipatory (provide for human energy needs). The justice claims made by the climate scientist are principally in the metaphysical dimension (life is sacred), with almost no anchoring in the conventional (given limited climate norms and a gap in global governance) and a countervailing positive emancipatory claim (free future generations from the unjust burden of the legacy we are bestowing upon them) as well as a negative emancipatory claim (we must confine ourselves to planetary boundaries). Within the existing justice matrix, the oil company executive wins, largely because the only signals of value that are made and received have to do with price and its relation to supply and demand. On the conventional economy’s mapping of efficiency and equity, the sanctity of life and what we owe to future generations (principally the metaphysical) remains tributary and ancillary to the subjective and the conventional; it is not even signaled in transactions.

The question becomes whether and how the contemporary justice matrix could be reconfigured to give a certain priority to the metaphysical over the subjective where planetary boundaries are at stake. At minimum, a metatheoretical approach reveals that if countervailing subjective justice claims were overcome, justice would have to be rendered to those whose claims were thus sacrificed. More ambitiously, a metatheoretical approach raises the question as to whether there is inadequate signaling within the existing economy for justice claims that are currently in deficit.

6. HOW THE FIDUCIARY PRINCIPLE OPERATES WITHIN A METATHEORETICAL CONCEPTION OF JUSTICE

To reconfigure the justice matrix, we must transform how we imagine our relationships with others and the world. This will require a new relationship to time and to the use and exchange of resources that eclipses the current formal use of law. Legal norms themselves will have to shift in real time in feedback to indicators warning of approaching planetary boundaries. All actors will have to be enabled to respond collectively to these signals. Fiduciary relationships can be used to model the transformation required.

A fiduciary relationship does not involve a self-reproducing norm that cuts off justice claims. Rather, it demands of all participants, even the courts, to conceive of the relationship, both in its process of articulation and its outcomes, as determined at the peril of the moment: exactly as the justice burdens we create are encountered. Indeed, that moment arises when authority is exercised in real time rather than in relation to a fixed norm, because to stand in that moment is to acknowledge the inadequacy of any outcome. For the fiduciary standard of care to be upheld, all of the fiduciary’s real-time resources must effectively be made available to address all claims. Despite the fact the fiduciary will rely upon bodies of specialized knowledge and metrics to measure relevant impacts, there is no way of fully automating either the fiduciary process or outcome. The fiduciary and the beneficiary are involved in a relationship—the reproduction of which subjects them both to running risks that can negate the legitimacy of the entire interaction. This is true of doctor and patient, for example, but it has also become true of the relationship between all of us and future generations.

The fiduciary relationship necessarily binds the resources of all participants, in contrast to delimited legal norms, outside the scope of immediately identifiable needs. The fiduciary relationship represents disparate justice claims or moments, and it is the means by which an otherness as relationship is maintained in requisite tension. The fiduciary’s obligation is to an outcome that exceeds the limits of fulfilling a prescriptive catalogue of duties; the prescriptive dimension, despite at times being questioned, is upheld regularly in the courts’ review of fiduciary inadequacies.

Thus, legal recognition of the fiduciary form comes closest to a methodology that would preserve the differentiation of incommensurable claims at the expense of formal, delimited law. It is a kind of productive paradox within the law, but one that can dissolve readily if the law cedes to the temptation to delimit narrow fiduciary norms.

To return a second time to the example of the oil executive and the scientist, to place the resolution of the conflict between discourses into a fiduciary setting would require differentiating and rendering justice to both sets of claims. This might mean, for example, charging the executive (or allied social interests) with the task of investing resources to enable a decrease in consumption and charging the scientist (or allied social interests) with the task of meeting energy needs more quickly through sustainable means at the same time as helping to identify unsustainable consumption that is to be excluded.

An articulation of the fiduciary principle is central to the justice foundations of ecological economics because it allows market outcomes to be situated against what we know concerning the implications for the prospects of life of each transaction. Because we do now know that every transaction does indeed produce (often) negative and (sometimes) positive social and environmental externalities, each transaction also comes bundled, so to speak, with a fiduciary burden. If this fiduciary burden is to be met, each of us must receive through other fiduciaries a signal as to the scope of the burden we are creating by our choices, such that each of our choices could themselves become fiduciary in character.

7. HOW CAN THE CRISES OF THE EXISTING ECONOMY ENABLE THE TRANSITION TO AN ECOLOGICAL ECONOMY?

If we must enable all transactions in an ecological economy to carry a fiduciary burden respecting the prospects of life, the difficult question of transitional justice arises: how can all of the investments made in the existing market economy be shifted to an ecological economy within a generation and with justice? Habermas’s treatment of legitimation crises focuses on capitalism’s almost infinite malleability to withstand contradictions (Habermas 1974). This stands in contrast to earlier Marxist accounts of capitalism that suggested that the crises of capitalism would produce the conditions to overcome it. History now suggests that capitalism is resilient and can shift its forms and functions. The working hypothesis of this section is that ecological economics would thus seek to penetrate and imbue capitalism rather than to overcome it.

Typically, the problem of transitional justice has been addressed retrospectively: given a great past injustice, such as apartheid, and a new social order, how is justice to be done (e.g., truth and reconciliation committees, lustration, trials, institutional reform)?8 However, the problem of transitional justice faced by ecological economics is prospective: given that the existing market economy is not ecologically sustainable, how is the injustice now being done to the future to be addressed?

There are two premises underlying this version of the problem of transitional justice. First, it is assumed that we can have a clear understanding of what an ecological economy would be—namely, one sustainably operating within planetary boundaries. It is not presumed, however, that we have a full understanding of the kinds of social and institutional arrangements that would allow an ecological economy to come into being and persist. Second, given our current scientific knowledge of the existing and widening transgression of planetary boundaries, it is assumed that the transition to an ecological economy is not in the nature of an incremental reform of existing economic practice. That is, if it could be assumed that the existing market economy is operating in a manner that is close to achieving an ecological economy and only requires regulatory adjustments, or that the transition to an ecological economy could take place gradually over a long period of time, our question would not focus on proximate transitional justice for the economy as a whole. Rather, the question would focus on incremental adjustments to regulatory regimes and managing implementation.

To illustrate the second premise, if it were assumed by contrast that the existing market economy could be brought sustainably within planetary boundaries by creating a carbon market and analogous markets for all ecosystem services—by putting a price on all environmental externalities—then the narrower transitional justice question would become as follows: how can the design of such markets be achieved, and what justice claims have to be resolved as those markets are brought into being? Such justice claims would include addressing the problem of common but differentiated responsibilities for the accumulated externalities (i.e., must there be compensation from those who have yet to produce externalities to those who have been and are producing them?), sharing the burden of sunk costs and stranded assets in economic processes being phased out (i.e., will that social burden lie entirely where it falls?), and identifying fair timelines for implementation (i.e., what is the reasonable planning horizon within which existing economic actors can adjust to new costs?). Such questions have to do with transitional justice in the face of incremental change. However, this is not our circumstance.

There is a point at which problems of transitional justice in the face of incremental change accumulate so as to become problems of transitional justice in the face of systemic change. Thus, for example, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (Montreal Protocol) gave rise to and sought to solve the transitional justice problems just identified for a discrete set of sectors of the economy. The phase-out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) affects the manufacture of refrigerants, solvents, and a narrow range of other processes. The adjustments required by the Montreal Protocol, while dramatic for those sectors, have been readily absorbed by the market economy as a whole. The Montreal Protocol does not therefore in itself give rise to systemic change. By contrast, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) gives rise to and seeks to solve transitional justice problems for the economy as a whole, given that GHG emissions arise from the production and consumption of energy and that the entire economy relies upon energy infrastructure. Even this observation would not yet entail that the UNFCCC gives rise to the problem of transitional justice in the face of systemic change. It could simply mean, for example, that a carbon or GHG tax would have to be applied so as produce an incremental shift in price signals, thereby allowing the existing market economy to align its use of resources with avoidance of the costs of climate change.

However, the UNFCCC does present certain hallmarks of the problem of transitional justice in the face of systemic change and in turn provides an indication that the even more substantial shift to an ecological economy—which could not be achieved by successful implementation of the UNFCCC alone—would indeed represent systemic change. Whereas the Montreal Protocol had to overcome strategic behavior and collective action on the part of those who were extracting rents from GHGs and HCFCs (e.g., there was a period of industry investment in ozone depletion denial and organized effort to discredit the science underpinning the Convention), the application of cost-benefit analysis taking account of the precautionary principle was straightforward: the potential harm to many overcame the vested interests of a few. By contrast, the significant range of social investments—rational and irrational—in existing modes of consumption (and indeed, in shared hopes for the prospects of future consumption) are widely perceived to be threatened by the UNFCCC process. Furthermore, the collective willingness to put off to future generations the accumulating and manifest damage to the biosphere suggests that we are in the midst of constructing a proximate future crisis on the implicit calculation that we should all seek to withdraw rents from the existing economy while we can. Finally, it is telling that there is increasingly common recourse to arguments that we need not address the looming catastrophe now because we will find and deploy cheaper technological solutions in the future to reverse climate change. Betting on the future to redeem the past suggests that we do not believe that present shifts in the economy would be incremental in the relevant sense. That is, we do not accept the anticipated costs of mitigating climate change now because we assume that this would impair our ability to benefit from the existing economy. In short, we are signaling the present incapacity of the existing market economy to absorb and avoid the costs of climate change and therefore are anticipating or courting systemic, albeit dystopian, change.

Systemic change from a market economy to an ecological economy will involve continuity with the existing market economy. This hypothesis may seem paradoxical, but the opposite hypothesis—discontinuity with the existing market economy—is on close inspection an impossibility. This is to say that the institutional and normative arrangements underpinning the market economy, as well as (and indeed most notably) the shared and generalized participation in consumption through the market economy, will not vanish at some discrete point of transition to an ecological economy. Even if the existing market economy were to be marked by energy or food crises, for example, it would still operate within those crises and establish transactions profiting from them. To date, the market economy has been capable of internalizing environmental externalities only if economic growth has not been at stake. It has proven incapable of a wholesale shift away from allowing externalities to be generated, because those externalities are intimately connected to economic growth.

Systemic change will nevertheless be accompanied by (and to a significant degree, given impetus by) a crisis of the existing market economy. Precisely because incremental change is unmanageable, the incapacity of the existing market economy to bring itself within planetary boundaries will manifest itself to the point of socially undermining the existing economy before systemic change is undertaken. That is, only at the point where there is general social disinvestment in the outcomes produced by the market economy will an ecological economy arise. The paradox to be confronted here is that consumers will cling to the market as citizens divest from it—but the consumers and citizens are one and the same.

Stewardship—or the exercise of fiduciary duty within the context of systemic change—involves seeking to fulfill a burden that can never be completely fulfilled. That is, because we cannot and should not seek to produce a discontinuity between the existing market economy and the ecological economy, the task will be to do what justice can be done within and out of a crisis of the market economy. We cannot simply posit the end state of an ecological economy and demand that it be substituted for the market economy.

It is the transformation—the in-between state—rather than the end state that becomes the focus of fiduciary duty and resources. The duty is owed to those who still rely on their consumer subjectivity and its legacy of claims. It is also owed to those seeking to overcome it and to those in the future who will not be able to rely upon it. Ascribing fiduciary resources to legacy justice claims is pure waste from the vantage point of producing an ecological economy, yet it is unavoidable as a matter of justice. Ascribing fiduciary resources to those now seeking to overcome consumer subjectivity is inherently beset with failure. Ascribing fiduciary resources to the future means enabling the fulfillment of unknown needs.

Although incremental change toward an ecological economy is here presumed to be beyond reach, given the need for systemic change, stewardship now involves in part identifying which sorts of incremental change might facilitate or at least be most consonant with systemic change. Thus, for example, whereas costing ecosystem services will not produce the requisite transition to an ecological economy because it will still place the transgression of planetary boundaries within a cost-benefit framework rather than setting a limit on transactions themselves, it would nevertheless bring within legal norms and institutional arrangements of the market economy enhanced capacity to steer within planetary boundaries. Another example is to build up and expand the fiduciary duties of existing economic actors themselves to consider, disclose, and account for their contribution of the transgression of planetary boundaries. Fiduciary stewardship also involves analyzing which existing economic processes and institutions are most prone to early system breakdown (e.g., perhaps the agricultural or energy sectors) and thus possible targets for more ambitious reform.9

Fiduciary stewardship also involves anticipating legal norms and institutional arrangements that could emerge through a process of systemic change and identifying their nascent forms in the existing market economy. The task would then become to help engender or reinforce those nascent forms. For example, we can safely assume that an ecological economy will require rigorous measurement of whether and to what degree planetary boundaries are being transgressed with feedback mechanisms to ensure that activities that collectively transgress are scaled back. Even if sustainable development indicators do not yet perform this function, they should be prepared and institutionalized with a view to enabling them to do so in the far more sophisticated way that will be required in the future.

Finally, and most problematically, fiduciary stewardship also involves beginning to work now on the implications of transgression of planetary boundaries—not simply from the standpoint of fending that off but also from the standpoint of modeling all of the justice claims that will arise as that unfolds. In this regard, the Cancun and Durban Summits speak volumes because the lion’s share of announced new funding are targeted to “adaptation” (although whether promises will be fulfilled is another matter). The investments being made in geoengineering are another sign.

Mitigation of climate change is already being cast institutionally as beyond reach. Our current fiduciary task is taken up, therefore, from the perspective that we will continue to consume up to and past the point where the planet has been made dramatically unliveable. The starkest problem of transitional justice is to take up the burden of planning for that outcome, both because its violent consequences cannot be pretended away and because a successful transition to an ecological economy might only be achieved with such consequences in view.

NOTES

1. A classic account of the basic forms of justice can be found in chapter 5 of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. See Aristotle (2011).

2. See also Shearman and Smith (2007), where the authors defend the thesis that democratic dysfunction over environmental issues could well lead toward authoritarianism in the absence of a major overhaul of democracy. See also Leo Hickman’s 2010 interview with James Lovelock, “Fudging the Data is a Sin against Science” (Guardian, March 29, 2010), where Lovelock is quoted as stating: “We need a more authoritative world. We’ve become a sort of cheeky, egalitarian world where everyone can have their say. It’s all very well, but there are certain circumstances—a war is a typical example—where you can’t do that. You’ve got to have a few people with authority who you trust who are running it. And they should be very accountable too, of course. But it can’t happen in a modern democracy. This is one of the problems. What’s the alternative to democracy? There isn’t one. But even the best democracies agree that when a major war approaches, democracy must be put on hold for the time being. I have a feeling that climate change may be an issue as severe as a war. It may be necessary to put democracy on hold for a while” (Hickman 2010).

3. See also Held and Hervey (2009) and Stehr (2013). Stehr wrote: “Climate researchers have evidently been impressed by Diamond’s deterministic social theory. However, they have drawn the wrong conclusion, namely that only authoritarian political states guided by scientists make effective and correct decisions on the climate issue. History teaches us that the opposite is the case. Therefore, today’s China cannot serve as a model. Climate policy must be compatible with democracy; otherwise the threat to civilization will be much more than just changes to our physical environment. In short, the alternative to the abolition of democratic governance as the effective response to the societal threats that likely come with climate change is more democracy and the worldwide empowerment and enhancement of knowledgeability of individuals, groups and movements that work on environmental issues” (citations omitted).

4. See Žižek (2006). Any economy purports to render justice. It is the collective management of resources for the oikos—our common household or home; the sphere we inhabit. The outcomes produced in the oikos with those resources are affirmed as legitimate as long as its foundational principles of allocation, production, development, and governance are just. Indeed, we should observe that the terms ecology and economy suggest two standpoints on the same sphere of oikos. One is the logos (science, knowledge) of what we inhabit; the other is the nomos (custom, law) of what we inhabit. Both standpoints give rise to their own theories (theorein: to look attentively on what appears). Thus the double standpoint of logos and nomos (ecological economics, which could also be economic ecology) suggests a metatheory—a theory of theories.

5. See Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1812), at paragraphs 9–13, where Smith makes clear that fellow-feeling is but the projection of our own sentiments upon the circumstances of the other should we bear them ourselves, notably against the backdrop of fear of death. This empties out the notion that we could act deeply or essentially for another.

6. On the relationship between justice and being held to account, see Butler (2005).

7. See in particular Latour (2013), who undertakes an ambitious modeling of how bodies of thought are networked but also remain opaque to each other.

8. See, for example, the work of the International Center for Transitional Justice (ictj.org).

9. Note, for example, that Canada’s National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (NRTEE), which had arguably sought to identify such opportunities, shifted toward identifying how to prosper from climate change: see National Round Table on the Environment and the Economy (2011), Climate Prosperity: The Economic Risks and Opportunities of Climate Change for Canada. As it was being abolished, NRTEE did publish a final series of four reports in 2012 signaling the need for significant change in the economy in response to the climate crisis.

REFERENCES

Aristotle. 2011. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Translated by Robert C. Bartlett and Susan D. Collins. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Beeson, Mark. 2010. “The Coming of Environmental Authoritarianism.” Environmental Politics 19 (2): 276–294. doi:10.1080/09644010903576918.

Burnell, Peter. 2009. “Should Democratization and Climate Justice Go Hand in Hand?” Böll Thema 2: 17–18.

Butler, Judith. 2005. Giving an Account of Oneself. New York: Fordham University Press.

Chaisson, Eric. 2006. Epic of Evolution: Seven Ages of the Cosmos. New York: Columbia University Press.

Derrida, Jacques. 1994. Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning, and the New International. New York: Routledge.

Fukuyama, Francis. 2011. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Habermas, Jürgen. 1974. Legitimation Crisis. Boston: Beacon Press.

Hardt, Michael, and Antonio Negri. 2000. Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Horkheimer, M., and T. W. Adorno. 1982. Dialectic of Enlightenment. Translated by John Cumming. New York: Continuum.

Kant, Immanuel. 2003. Critique of Pure Reason. Translated by Norman Kemp Smith. Revised 2nd ed. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kleinhans, Martha-Marie, and Roderick A. Macdonald. 1997. “What Is a Critical Legal Pluralism?” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 12: 25–46.

Latour, Bruno. 2013. An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the Moderns. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Posner, Eric A., and David A. Weisbach. 2010. Climate Change Justice. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rawls, John. 1993. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press.

Schlosberg, David. 2012. “Climate Justice and Capabilities: A Framework for Adaptation Policy.” Ethics & International Affairs 26 (4): 445–461. doi: doi:10.1017/S0892679412000615.

Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

Sen, Amartya. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Shearman, David J. C., and Joseph Wayne Smith. 2007. The Climate Change Challenge and the Failure of Democracy. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

Smith, Adam. 1812. The Theory of Moral Sentiments. 11th ed. London.

Stehr, Nico. 2013. “An Inconvenient Democracy: Knowledge and Climate Change.” Society 50 (1): 55–60. doi: 10.1007/s12115–012–9610–4.

Wilson, Edward O. 2004. On Human Nature. Revised ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2006. The Parallax View. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2008. In Defense of Lost Causes. London: Verso.