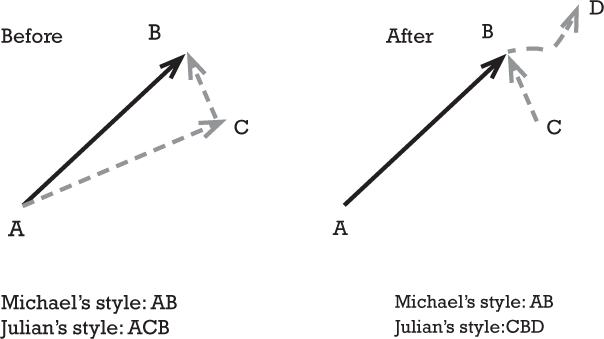

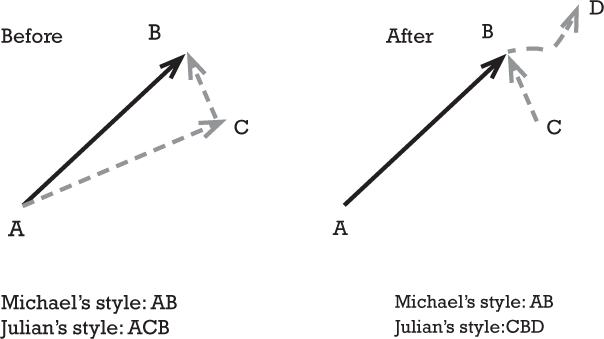

Diagram 10.1: Two styles of management

Many managers struggle with the notion that they need to coach their people. There are two arguments they have against this:

1. They were never coached by their bosses. Yet they have been able to learn things on their own and are obviously pretty successful. So why should they coach their people?

2. It is so time-consuming. Sitting down to coach someone requires a lot of patience and takes up precious time. And what irks them further is that despite this effort, the subordinate may still be unable to accomplish the work to the quality that is expected. And so they conclude, “Why waste time? If I do the work on my own, it is not only much faster but also better.”

When I discuss coaching, I usually say upfront that coaching is not entirely an act of altruism. It is also because of enlightened self-interest. Why so? Because as managers we need to work through our people. If we have capable and motivated people on our teams, our work gets done more efficiently and we achieve the success that we desire. Otherwise, we’ll struggle and work very long hours doing what our people should be doing. And because of that, we won’t have time for more strategic matters that we may need to focus on. This will ultimately mean that we won’t be giving to our organization the values that they expect of us.

In a nutshell, there are four compelling reasons for coaching your people:

♦ It is a social responsibility of all managers to invest in developing their people. If our bosses did little to develop us in the past, it does not mean we should perpetuate their act of omission. Managers are part of a privileged group. By passing on our learning, we contribute to a better workplace and society.

♦ It raises the capabilities of your people. When they become successful, you become successful.

♦ You will develop a reputation as a developer of people and become a magnet for talent. And if you look around, you will notice that highly successful leaders attract great people to their teams.

♦ You will free up time to focus on the higher value-added activities that a manager needs to deliver. This is how you can make a more impactful contribution towards the overall objectives of your organization.

All these benefits will accrue only if you make the investment in time and effort upfront. Let’s now address the second argument against coaching. This is best done by studying the methods adopted by two managers, Michael and Julian.

Michael is a long-serving manager who has risen from the ranks. He has never been coached in all his career. Two years ago, he became the manager of a team of service engineers. To him, the best way of getting things done is to issue clear directions to his people and have them come back to him regularly for more clarification if they are unclear. He applies this same approach to all five engineers.

It seems to work well. Things get done and he is always on top of the situation. Though he is involved knee-deep in all the nitty-gritty, he doesn’t mind. Most days he comes to work very early in the morning and is never home until very late at night when all his children are already in bed.

If you talk to him, he frequently laments his engineers’ lack of ability to think and act independently. Though they are relatively experienced, they seem constantly in need of guidance and assurance. In truth, he is rather disappointed that after two years of hand-holding from him, he is still as busy as when he first became a manager. His boss has been asking him to delegate and let go so that he can take on other responsibilities. But alas, how can he do that? It seems to him things will surely fall apart because his engineers just aren’t ready. Letting go seems too risky a venture for him.

Julian has recently been promoted to manage a team of three accountants. Before his promotion, he attended a programme to equip managers with coaching skills. He is therefore keen to put these skills to work.

He has spent quite a lot of time establishing a trusting relationship with each of his subordinates. They are all relatively inexperienced, none having had more than a year on the job. Whenever he assigns them a piece of work, he will spend time providing the necessary background information, and define what the expectations are. He also makes time for his people to ask questions. They then agree on how frequently there will be follow-up sessions to check on the work progress.

When his people come back to him for clarification, he has sometimes been tempted to just tell them what to do and get on with it. Perhaps, that may hasten the pace of work. Fortunately, he has been able to restrain himself. Instead, he asks them questions and encourages them to think of their own solutions. If they are really stuck, he will offer suggestions though. “Oooh…,” he groans, “it’s so time-consuming.” But he persists.

This process has been continuing for more than six months. And slowly but surely, he notices a change in his people. They are more self-assured now. When he delegates a piece of work now, they react quite confidently and will ask some pointed questions to ensure alignment in terms of expectations and outcomes. Then they are off on their own. During their periodic progress reviews, the work will have advanced considerably in the right direction.

Julian is a happy camper these days. He continues to coach his people but they seem to need much less attention from him. With the spare time freed up, he plans ahead. His boss has complimented him for being proactive. His team is performing very well and their morale is the highest in the company.

Let’s first do a quick diagnosis of these two different styles of management.

Diagram 10.1: Two styles of management

In the beginning, Michael’s directive style (AB) is more efficient, while Julian’s coaching approach (ACB) is very time-consuming. As you can see, ACB is a crooked line and is longer than AB which is the straight line between A and B.

Sometime later, the situation has flipped around. While Michael continues with his directive style, his people have gone no further. They are still stuck at A. In contrast, Julian’s people have gained in competence and experience. They are now at C. Getting from C to B is a shorter and faster route than from A to B. And Julian now has extra time to focus on more strategic activities from B to D.

Doesn’t this remind you of the fable of the hare and the tortoise racing each other? Julian, the tortoise, has had a slow start but at mid-point he surpasses Michael, the hare, and leaves him in the dust.

“Give a man a fish, he eats for a day. Teach him how to fish, he eats for a lifetime.”

— Old Chinese saying

Before we conclude our discussions about the two different styles adopted by Julian and Michael, I would like to share with you some comments made by a reviewer of this book. She said that although she would clearly prefer Julian as a boss, Michael didn’t seem bad compared to another manager, Rostam, whom she knew.

Rostam, a communications manager, rose from the ranks in the company. Along the way, he acquired a manipulative style of management that relied on the use of hard power. To him, his divisional KPIs were the be-all and end-all. He ran his team like a “pompous dictator”, coercing them to produce results at all cost. Distant and dismissive, he soon lost touch with what was happening around him. Whenever his subordinates came to him with queries, he was frequently unable to provide any guidance. He would resort to an old trick: throw the question back to his people. Then he would declare, “A good coach never provides answers. My questions are to challenge you to think on your own!”

Left on their own, his people ploughed on. Although they did meet the targets set, they became increasingly disenchanted and resentful that their boss was reaping huge bonuses by cracking the whip from the comfort of his desk.

The purpose of coaching is to enable others to discover solutions for themselves. It is different from teaching or training. In training or teaching, the spotlight is on the teacher or trainer. He is the person with knowledge and expertise to impart. He tells the learner what he needs to know and the learner takes it all in. Usually, the interaction is one way: from the teacher /trainer to the learner.

In contrast, a coaching relationship adopts a learner-centric approach. The spotlight is on the coachee. The coach does not play the role of an expert. He is a dialogue partner whose main purpose is to facilitate discovery of solutions through thought-provoking questions. By being an empathetic listener, the coach creates a safe place for the coachee to share what is on his mind. This is key to facilitating the coachee’s learning as he will learn best when there is encouragement to raise questions and express his own opinions. In this way, the exchange becomes dynamic and two-way. Through this process, the coachee actively explores various options, and then comes to a conclusion about what works and what does not.

At the end of a good coaching conversation, both the coach and coachee should feel that something meaningful has taken place. The coachee has greater clarity of what he wishes to do and is committed to making it a reality.

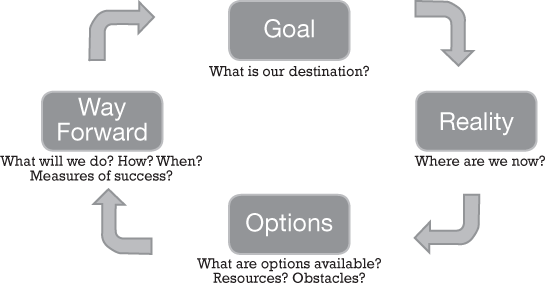

How does one conduct a coaching conversation? I would like to introduce a simple and easy to use framework called The GROW Model. It consists of four steps. In the description below I will refer to the manager as the coach and the co-worker as the coachee.

Step 1: Goal

Discuss and agree with coachee on the topic and objectives of the discussion.

As a simple example, let’s say that the coachee is habitually late in submitting a sales status report at the end of the week. The goal is to help him identify and take actions to submit his report on time.

Ask the coachee what the current situation is.

He acknowledges that his report is usually late by an hour. He is aware that the deadline is 3 p.m. on Friday.

Step 3: Options

Between the Goal and the Reality, is the Gap. What are some possible options to bridge the gap?

The coachee is encouraged to come up with his own options. Some of his suggestions are: (a) Start working on the report the day before and not wait till Friday morning when he gets overwhelmed by other urgent work, (b) … (c)…

Step 4: Way Forward

Among the options discussed, what appear most practical? Are there any obstacles that may prevent him from taking any of the options? If so, what does he need to do? When will he implement his plan? At the end of Step 4 there needs to be a commitment on actions. A coaching session is meaningful only if an action plan is the result. In the days ahead, the coachee will turn his action plan into reality.

Diagram 10.2: The GROW Model

The four-step framework is easy to understand and apply. However, to be an effective coach, we need more than just a framework. Owning a sleek-looking set of golf clubs, for example, does not make one a good golfer. In both situations, we need certain proficiencies. We will talk more about these in the next chapter.

♦ Coaching is not an entirely altruistic act. Both the managers and their subordinates will derive immense mutual benefits.

♦ The GROW model is a simple and practical framework for a coaching conversation.

Q1: According to Rostam, “A good coach never provides answers!” Do you agree with him?

Q2: When you coach, what steps can you take to help the coachee learn how to fish and feed himself?