For years, those concerned with the suffering and ordeals of the people of Afghanistan found it difficult to gain a hearing in the precincts of “high politics,” where security dominated. Afghanistan was defined largely as a “humanitarian emergency” to be treated with charity. Leaders of some neighboring states, especially those from Central Asia, argued repeatedly that the failure to rebuild Afghanistan and provide its people with security and livelihoods threatened the region. Since 1998, an increase in what may, in retrospect, be called relatively small acts of terror traced to the al-Qaeda organization placed Afghanistan on the global security agenda. But the means chosen to address the threat—sanctions against the Taliban combined with humanitarian exceptions, with no reference to the country’s reconstruction—showed that those setting the international security agenda had not drawn the connection between the terrorist threats to their own security and the threats to human security faced daily by the people of Afghanistan.

The Afghan people have for more than twenty years faced violence, lawlessness, torture, killing, rape, expulsion, displacement, looting, and every other element of the litany of suffering that characterizes today’s transnational wars. Groups aided by foreign powers have, one after another, destroyed the irrigation systems, mined the pastures, leveled the cities, cratered the roads, blasted the schools, and arrested, tortured, killed, and expelled the educated. Statistics are few, but a 1988 study by demographer Marek Sliwinski estimated that “excess mortality,” in his phrase, amounted to nearly one-tenth of Afghanistan’s population between 1979 and 1987.

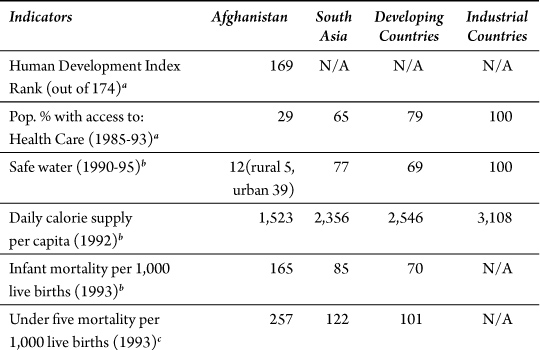

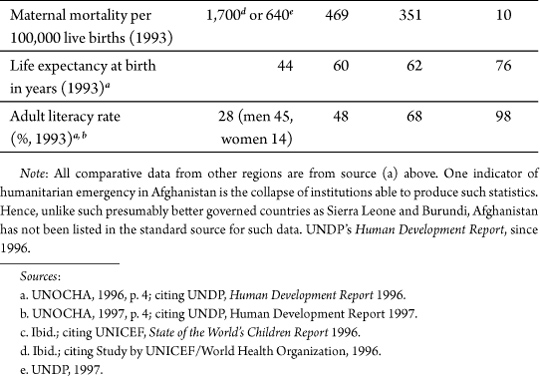

Some results of this destruction are summarized in Table 4.1. It shows that by whatever measure of human welfare or security one chooses–life expectancy, the mortality of women and children, health, literacy, access to clean water, nutrition—Afghanistan ranks near the bottom of the human family. But this table shows something else as well. The figures in it are all rough estimates compiled by international organizations. Afghanistan is no longer even listed in the tables of the World Development Report published yearly by the United Nations Development Program, because it has no national institutions capable of compiling such data.

Table 4.1 Measures of Human Security in Afghanistan

In a widely reprinted 1981 lecture, Professor Amartya Sen compared the records of China and India in food security, particularly in the prevention of famine, and demonstrated a fundamental result: access to information is a chief guarantor of human security. Sen showed that the restrictions placed on freedom of expression by the Chinese government allowed famine to rage unchecked during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s, whereas India’s freer system more easily halted such disasters.

Afghanistan also faces a challenge of information, but an even more fundamental one than 1950s China: it has no institutions capable even of generating information about the society that could be used to govern it. Over the past two decades Afghanistan has been ruled, in whole or in part, at times badly and at times atrociously, but it has not been governed. Above all, the crisis of human security in Afghanistan is due to the destruction of institutions of legitimate governance. It is as much an institutional emergency as a humanitarian one. Accountable institutions of governance that use information to design policies to build the human capital of their citizens and support their citizens’ economic and social efforts and that allow others to monitor them through the free exchange of information are the keys to human security.

The insecurity due to the absence of such institutions and the effect on the population accounts for many threats that Afghanistan has posed. The rise and fall of one warlord or armed group after another is largely the result of the ease with which a leader can raise an army in such an impoverished, ungoverned society. One meal a day can recruit a soldier. No authorities impede arms trafficking, and no one with power has had enough stake in the international order to pay it heed.

The expansion of the cultivation and trafficking of opium poppy constituted a survival strategy for the peasantry in this high-risk environment. Opium cultivation supplied not only income and employment but cash for food security. Before 1978 Afghanistan was self-sufficient in food production, but it now produces less than two-thirds of its food needs. Futures contracts for poppy have constituted the only source of rural credit, and only the cash derived from these futures contracts enabled many rural families to buy food and other necessities through the winter. The ban on opium cultivation by the Taliban during their last year in power met one Western demand, but donors withdrew even the previously meager support for crop substitution, although pilot programs had shown some success. Cultivators and laborers suffered, while the regime continued to profit from unhindered trafficking at inflated prices of stocks remaining from two years of previous bumper opium crops.

The lack of border control, legitimate economic activity, and normal legal relations with neighbors, combined with disparities in trade policy between the free port of Dubai and the protectionist regimes elsewhere in the region, made Afghanistan a center of contraband in all kinds of goods. This smuggling economy provided livelihoods to a sector of the population while undermining institutions in Afghanistan’s neighbors.

The lack of any transparency or accountability in monetary policy since the mid-1980s has both resulted from and intensified the crisis of institutions. Governments or factions posing as governments received containers of newly printed currency, which they transferred to militia leaders or other clients to buy their loyalty, bypassing the inconvenience of taxation or nurturing productive economic activity. Several currencies remain in circulation, none of them backed by significant reserves of a functioning bank. The resultant hyperinflation has driven wealth out of the country and contributed to the already bleak prospects for investment. It virtually wiped out the value of salaries paid to government workers, including teachers, undermining the last vestiges of administration and public service, except where international organizations paid incentives to keep people on the job. Since the inauguration of the Interim Administration of Afghanistan on December 22, 2001, government employees have received salaries monthly, thanks to foreign donors, although they have barely met the deadlines.

This is the context in which Afghanistan became a haven for international terrorism. The origins of the problem date to the creation of armed Islamic groups to fight the Soviet troops and the government they had installed. Islamist radicals, mainly from the Arab world, were recruited to join the ranks of the mujahidin. But the Afghans did not want these fighters to stay after the Soviet troops left in 1989. If the people of Afghanistan had been able to rebuild their country and establish institutions of governance, they would have expelled the terrorists, as they are doing today. But in the atmosphere of anarchy and lawlessness, the armed militants were useful to some Afghan groups and their foreign supporters.

The money that could be mobilized by Usama Bin Laden and his networks also played a role. As the Taliban, in particular, became increasingly alienated from the official international aid community, with their various strictures and demands concerning the status of women and other matters, they increasingly turned to this alternative unofficial international community. The financial and military support they received helped cement the ideological and personal ties that grew between the top leadership of the Taliban and al-Qaeda. In an impoverished, unpoliced, ungoverned state with no stake in international society, al-Qaeda could establish bases to strengthen and train its global networks.

That network’s most spectacular act of terrorism, on September 11, revealed the dangers of allowing so-called humanitarian emergencies or failed states to fester—dangers not only to neighboring countries but to the world. An American administration that came to power denouncing efforts at “nation building” and criticizing reliance on international organizations and agreements has now proclaimed that it needs to ensure a “stable Afghanistan” to prevent that country from ever again becoming a haven for terrorists. The United States, along with every other major country, has committed itself to supporting the reconstruction of Afghanistan within a framework designed by the United Nations.

The Agreement on Provisional Arrangements in Afghanistan Pending the Reestablishment of Permanent Government Institutions—to give the December 5, 2001, Bonn agreement its full and accurate title—resulted directly from this new level of commitment by both Afghans and major powers. Most reports on this agreement treat it as a peace agreement, like those that have ended armed conflicts elsewhere. But in Bonn the UN did not bring together warring parties to make peace. The international community has defined one side of the ongoing war in Afghanistan—the alliance of al-Qaeda and the Taliban—as an outlaw formation that must be defeated. In Bonn the UN brought together Afghan groups opposed to the Taliban and al-Qaeda, some possessing power and other forms of legitimacy, notably through Muhammad Zahir Shah, the former king of Afghanistan. They set themselves the central task of protecting human security: starting the process of establishing—or, as the Afghans insisted, in recognition of their long history, reestablishing—permanent government institutions.

This agreement thus differs from many others that, as critics have noted, sometimes amounted to the codification of de facto power relations, no matter how illegitimate. This agreement does recognize power especially in the allocation of key ministries to the relatively small group that already controlled them in Kabul thanks to the U.S. military campaign. In most respects, however, the Bonn agreement attempts to lay a foundation for transcending the current rather fragile power relations through building institutions.

The Interim Administration of Afghanistan established by the agreement will include three elements: an administration, a supreme court, and a special independent commission to convene the Emergency Loya Jirga (national council) at the end of the six-month interim period. It also requested an international security assistance force, one of whose major purposes is to ensure the independence of the administration from military pressure by power-holding factions.

The Bonn agreement does not contain a supreme or leadership council composed of prominent persons. Such institutions in previous Afghan agreements gave legitimacy to de facto power holders, including those whom some call warlords, as well as leaders of organizations supported by foreign countries. Some of the discontent with the agreement derives from the fact that it does not give recognition to such leaders. Many Afghans seem to consider this a positive step.

Instead the agreement emphasizes the administration. The term “administration” rather than “government” indicates its temporary and limited nature, but it also emphasizes that the role of this institution is actually to administer—to restore services. The presence of the supreme court as well as measures defining an interim legal system require this administration to work according to law; the chair of this administration, Hamid Karzai, has also emphasized this. Some had hoped that this administration would be largely professional and technocratic in character, and that is certainly true at least of its women members. In Afghanistan as elsewhere, women can usually obtain high positions only by being qualified, whereas men have other options for advancement.

Some little-noticed elements in the agreement are designed to strengthen the ability of the administration to govern through laws and rules and provide for transitions to successively more institutionalized and representative arrangements. The international security assistance force should insulate the administration from pressure by factional armed forces. At the insistence of the participants, the judicial power is described as “independent.” The Special Independent Commission for Convening the Emergency Loya Jirga has many features to protect it from pressure by the administration, including a prohibition on membership in both. The Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) for Afghanistan is also given special responsibility for ensuring its independence.

The agreement confronts the country’s monetary crisis by authorizing the establishment of a new central bank and requiring transparent and accountable procedures for the issuance of currency. This measure is partly aimed at ensuring that the authorities will be able to pay meaningful salaries to officials throughout the country, thus reestablishing the administrative structure that has been overwhelmed by warlordism. Appointments to the administration are to be monitored by an independent Civil Service Commission. Although this body will face severe constraints, it is aimed at curtailing arbitrary appointments, whether for personal corruption or to assure factional power. The Civil Service Commission will be supplemented with a formal Code of Conduct, with sanctions against violators. For the first time, the Afghan authorities will establish a Human Rights Commission, which will not only monitor current practice but also become the focal point for the extremely sensitive discussion about accountability for past wrongs. The SRSG also has the right to investigate human rights violations and recommend corrective actions.

The agreement provides for the integration of all armed groups into official security forces. Although this is not what specialists refer to as a “self-executing provision,” other measures will reinforce it. The international security force will assist in the formation of all-Afghan security forces. Monetary reforms and foreign assistance to the authorities may enable the latter to pay meaningful salaries to soldiers and police, providing an incentive for them to shift their loyalties from warlords. The latter may become generals, governors, politicians, or businesspeople, as institutions are built and the economy revives.

Building these Afghan institutions will constitute the core task of protecting human security in Afghanistan. The agreement provides a framework. But implementation in such a war-torn and devastated society will largely depend on how the international donors and the UN system approach the task of reconstruction.

As donor agencies and nongovernmental organizations rush in, they risk losing sight of the central task: building Afghan institutions owned by and accountable to the people of Afghanistan. The Bonn agreement states that the SRSG “shall monitor and assist in the implementation” of the agreement, but it does not establish a UN transitional administration in Afghanistan. It vests sovereignty in the Interim Administration. The Afghan participants at the meeting scrutinized every provision that provided for international monitoring or involvement to ensure that the new authority would be fully sovereign. The lessons of the past two decades in Afghanistan and elsewhere are that only accountable and legitimate national institutions, although open to the outside world and subject to international standards, can protect human security.

There is a real risk that the actors in the reconstruction market, as they bid for locations in the bazaar that is opening in Afghanistan, may harm, hinder, or even destroy the effort to build Afghan institutions. Donors and agencies seeking to establish programs need to find clients, and it is often easier to do so by linking up directly with a de facto power on the ground. Such uncoordinated efforts have reinforced clientelism and warlordism in Afghanistan for years in the absence of a legitimate authority. Programs must now be coordinated to ensure that they work together to reinforce the capacities and priorities of Afghan institutions. At the January 2002 conference on reconstruction in Tokyo, Chairman Karzai asked the donors to coordinate, and the conference established an “Implementation Group” chaired by the Afghan administration in Kabul to monitor the effort. The group has yet to meet, but bilateral donors and NGOs are already racing to duplicate projects, and Afghan ministers spend so much time traveling abroad and meeting delegations that they have little time for their primary task: reestablishing governance.

The growing international presence, with high salaries and big houses, is already overwhelming the new administration and distorting the economy. Rents for large houses in central Kabul have risen from $100 to $10,000 per month; Afghan NGOs can no longer afford office space in the center of the capital. When the mujahidin took power in Herat in 1992, the city had ten qualified Afghan engineers working in the municipality. Before long it had only one since the other nine went to work as drivers for UN agencies, where they earned much higher salaries. These are just some examples of how the normal operation of the international aid system can actually deprive countries of the capacities they need.

If the vast sums that seem to be flowing toward Afghanistan are to help reinforce rather than undermine the fragile institutions established in the Bonn agreement, international actors must establish new bodies to monitor and control the disbursements in partnership with the Afghan authorities. The expenditures must follow the priorities they set in consultation with the SRSG, not the multiple priorities set by the agendas of various countries or agencies. The international community may have to sacrifice some of its immediate interests, but as it has learned only too bitterly, it is worth paying a modest price to protect the self-determination and human security of the people of Afghanistan. The international community’s own security depends on it.