The appropriate mandate for peace-keeping or security forces in postconflict or peace-building operations has been one of the most difficult and contentious issues since the end game of the Cold War led to the increasing involvement of the UN in multifunctional operations. The controversy over the enforcement of provisions on demobilization and human rights in Cambodia and, especially, the disasters that overtook UN forces in Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina led to evaluations of what went wrong.1 In one influential analysis, Steve Stedman argued against the assumption that international forces were always present to overcome security dilemmas and monitor compliance with an agreement; instead he argued there are often actors, labeled “spoilers,” who use violence to prevent implementation and that mandates needed to change accordingly. The 2000 Brahimi report on UN peace operations adopted the category of “spoilers” and argued that troop deployments, mandates, and resources must correspond to a realistic threat assessment, rather than to existing doctrine or the degree of interest of the Security Council or troop contributors.2

The insurgencies and civil conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq have similarly drawn attention to the primacy of security in state-building operations that take place without a comprehensive peace agreement (as in Afghanistan, where the Bonn Agreement did not include the apparently defeated Taliban) or with no agreement or international mandate whatever (as in Iraq). Many observers have argued that more security forces, better coordination, and other changes of strategy are needed for “success.”3 Yet sending even more troops into Iraq has been even less successful in providing security than in Afghanistan.

All such operations aim at political objectives, not just building “states,” let alone “peace,” and their success is crucially linked to the international and domestic legitimacy of those objectives and the ability of leaders to mobilize people to defend them. The challenge of legitimacy is doubly difficult in such operations because even though state building always requires a struggle for legitimation among citizens, internationalized operations must also meet a high standard of international legitimation, including appropriate authorization and political support in each of the states that provide financial or military aid. These various sources of legitimacy may contradict as well as complement each other. Understanding the challenge of providing security in internationalized state building or peace-building operations requires situating both the operations and the accompanying efforts to provide security in their political context. This chapter first examines the concept of security in internationalized state-building operations and analyzes its relation to other components of the state-building process.

Using this conceptual framework, the paper then examines several political issues relating to security in such operations. These include the legitimacy of the international security deployment with both the citizens of the affected state and the international community; whether international deployments support or displace the creation of national capacity; the relation of security sector reforms to both interim power-sharing arrangements and the transition to permanent institutions; priorities among different types of security and security institutions; the need for legitimation, among the general population but particularly within the security forces; and sustainable finance for the security sector. Throughout these sections, I draw extensively on the case of Afghanistan, partly because I have followed the country for more than two decades and advised the United Nations during the postwar transition period, but also because the case exemplifies many of the key claims of this chapter. Finally, the paper draws on this analysis to discuss some major questions over the sequencing and interrelationships of various components of peace-building and state-building operations, in particular the relationships among security, democratization, and reconstruction or development. The interdependence of security, legitimacy, and economic development in the state-building process provides a framework for a comprehensive analysis that transcends the usual stovepiped discussions of peace keeping, security sector reform, reconstruction, and governance.

Operations known as “postconflict,” “reconstruction,” “peace building,” or “stabilization” do not form a homogeneous group. Despite the recent emergence of some of these terms, such operations have a long history.

The use of international coercive forces as part of an operation aiming to build national capacity (rather than absorb a territory as an imperial or colonial possession) represents the latest historical iteration of interaction between powerful states’ self-interest and the prevailing juridical forms of power, especially state sovereignty.4 Internationalized state building responds to the problem of maintaining security, however defined, in a global system juridically and politically organized around universal state sovereignty. With the construction of more tightly linked systems of mutually recognized and demarcated states in post-Westphalian Europe, the quest for security and profit on the periphery became an imperial—and ultimately global—extension of interstate competition among core states. The contemporary global framework for security developed with the foundation of the United Nations system after World War II. That system extended the international regime of national sovereignty enshrined in the charter, both by legitimizing recognized states as actors on the international stage (the UN’s “member states”) and by delegitimizing colonialism and imperialism as legal doctrines.

During the Cold War, the struggle over building postcolonial states largely took the form of competing foreign aid projects by the alliance systems led by the United States and USSR. The end of the Cold War freed the UN and some regional organizations to replace unilateral clientelism with multilateral state-building efforts, especially in countries emerging from internal wars. Agreement by the Security Council to entrust most such operations to the UN reflected both the end of zero-sum strategic competition and the lowering of the stakes in who controlled these states.

The attack of September 11 showed that the United States could now be attacked from even the weakest state and hence reignited strategic interest of U.S. nationalists in the periphery. Because the regime of universal sovereignty prevents such peripheral territories from being absorbed into more powerful units, however, international security after September 11 requires the transformation or strengthening of existing national states. Consequently, current internationalized state-building operations, even those labeled “peace building” or “stabilization,” reflect the impulse of Western powers to exercise influence.5 The terminology deployed, the very endeavor to “build” states, and the process by which international mandates are defined and undertaken all reflect an inherent political dimension, one that is not benign and selfless, but self-interested and instrumental.

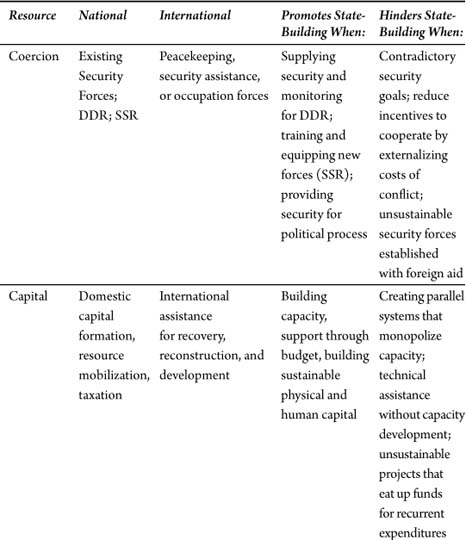

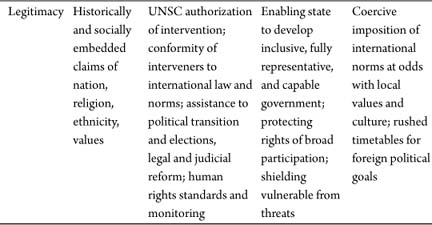

International participants in peace-building or stabilization operations attempt to build states in accord with their interest in areas that pose a perceived threat to them. Such operations make use of the same types of resources as other processes of state building: coercion, capital, and legitimacy. This section elaborates on the international tools, and the positive or negative effects of these state-building resources. When the intervention occurs in a country where state power is weak or contested, preventing relapse to war requires the interveners to jump-start the mutually reinforcing process of security provision, legitimation of power, and economic development by providing international resources or capacities to cover initial gaps in all three. Coercion includes transitional international security provision or intervention (peacekeeping, peace enforcement, security assistance, or occupation); the demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration (DDR) of at least some combatants; and the building of new security agencies or reform of existing ones (security sector reform, SSR). Capital takes the form of both international financial assistance for recovery, reconstruction, and development and of efforts to invigorate the national economy and the fiscal capacity of the government. The legitimacy of the operations derives from both the legitimacy of the international operation or intervention and that of the system of rule that this operation tries to institutionalize. The outcome depends on initial conditions and the combination of national and international capacities in these areas.6

In the best case, such transitional assistance will help launch a new self-sustaining dynamic, but there is a danger, to borrow terms from public finance, of “crowding out” as well as “crowding in.”7 Crowding out occurs when international efforts or structures displace existing or potential new domestic-level state institutions that might carry out similar functions—i.e., hindering state building. Crowding in occurs when international efforts or institutions provide the space, resources, or training and mentoring for domestic-level actors or institutions in ways that enhance their capacity and potential sustainability—i.e., promoting state building. These possible interactions and their effects are illustrated in Table 10.1.

International security provision may provide a sheltered environment for building national security forces, or it may give contending factions the space to continue to feud without confronting the consequences. External financial aid may fund the creation of national capacities, the building of institutions, and development, but it can also create parallel systems that suck capacity out of national institutions and create unsustainable white elephants: roads that cannot be maintained, overpasses to nowhere, schools with no teachers, or “security” forces with no salaries. International support may strengthen the legitimacy of interim or transitional arrangements through authorization by the Security Council and guarantees of respect for human rights and secure political participation for all; but it may also undermine legitimacy by weakening incentives for leaders to be accountable to citizens or exposing conflicts between local and international standards, as in the case of the apostate Abdul Rahman in Afghanistan. To what extent states built in this manner exercise power as sovereigns, in the service of nationally determined goals, and to what extent they act as agents of externally defined interests, constitutes the “dual legitimacy” problem of global state formation.8

Table 10.1 Resources for Internationalized State Building and Their Interactions

In the 1990s, UN peacekeeping mandates underwent a shift that would prove crucial for understanding “security” in postconflict operations. In the early 1990s they presumed full agreement among warring parties and full legitimacy of the operation among all parties. This produced what some have called “warlord democratization,” where armed groups voluntarily demobilize in order to resolve a security dilemma, requiring confidence-building measures enforced by peacekeepers.9 Here the main task is protecting the security of the former combatants. The disastrous UN operations in Rwanda and Bosnia along this model led to interventions with stronger mandates.10 Hereafter the UN would not act only with consent but also authorize the use of force against “spoilers” seeking to block implementation of agreements or fight their way into a better deal.11 But the change in the situations in which intervention occurs has required more than a change in security mandates. Security mandates are always closely tied to legitimacy.

In 1985, UN special envoy Diego Cordovez told me that “the UN is not in the business of changing the governments of member states.” Only two years later, however, as the talks that led to the Geneva Accords on Afghanistan reached their end game, Cordovez himself became involved in just such an activity. Since then, internationalized “postconflict” operations have usually taken place after internal war, though some parties may continue fighting after the so-called postconflict operation starts. The stake is precisely the nature of the government and who controls it.

The term security, like peace building, contains an embedded political claim. Consistent with the use of technocratic language that obscures political issues, debates over security often neglect to define whose security is at stake and for what purpose. Conventional means of providing security through the use or threat of force and violence rely on the paradox of security provision: making some people and institutions secure by making those who would threaten them insecure. In its conventional use to denote the goal of military and police operations, “security” means the use or threat of legitimate force to prevent illegitimate violence. The claim that any specific use of force creates “security” is a political claim that the force is legitimate and that those against whom it is directed are outlaws or “spoilers.” The transformation of coercion into security through the rule of law, as much as the transformation of predation into taxation through accountability and service provision, are essential to building legitimacy as part of the process of state building.

The transformation from civil war to “peace,” whether the latter is defined negatively as the absence of war or positively in terms of sustainable human security, requires transformation in the organization and control of the means of violence. Given a state of civil war, at least some armed groups are outside state control. In the course of such wars, both states and nonstate armed groups often create multiple, unaccountable, politicized armed forces. Other parts of the security sector, such as police, public prosecutors, and the judiciary, are likely to be weak, corrupt, or subordinate to the political demands of civil warfare. Armed groups rather than civilian political parties or institutions are likely to have become the principal means used for political contestation or gaining control of assets. The interrelated establishment and stabilization of control of the means of legitimate violence and authority, combined with mobilizing the resources to sustain these institutions, constitutes the process of state building.

Parties to a civil conflict resolved by means other than partition have to be integrated into a common state.12 In the usual cliché, they must substitute “ballots for bullets,” that is, settle differences through a civilian political system, in which violence is regulated by law for public purposes (security), not used as the premier tool of political competition. The process of building security institutions after a civil war is not only a technical task of building capacity but also central to the distribution of political power that makes a settlement possible. It requires both political legitimacy and a fiscal basis that makes the institutions sustainable. Given the weakness of civilian institutions, the very process of empowering the latter is political, independently of the explicit struggle over who controls those institutions. As argued in the previous chapter, DDR and SSR are technical terms for historical processes essential for state building. This in turn requires building states with sufficient legitimacy and capacity to allocate resources and resolve disputes without overt violence. In the rare event that international actors assist in establishing a new state (East Timor, potentially Kosovo), the previously subordinate territory needs support and aid to develop the capacity to exercise self-government.13 [Kosovo was recognized by the United States and members of the European Union (among others) as the independent “Republic of Kosovo” in 2008.]

The outcome of peace-building processes depends both on the degree of difficulty and the amount and effectiveness of international resources deployed. Doyle and Sambanis analyze what they call the “Peacebuilding Triangle,” the dimensions of which are determined by three factors: the severity of the conflict (measured by numbers of casualties and refugees, whether or not the conflict is ethnic, the degrees of ethnic and political fragmentation, and the outcome of the war before the operation); national capacities for peace (measured by levels and type of economic activity and human development); and international capacities (measured by type of mandate, and size of the international intervention).14

The first two dimensions define the initial conditions. One can characterize the initial security conditions, as noted in the previous chapter, as the degree of accumulation and of concentration of violence. These are roughly equivalent to Doyle and Sambanis’s measures of conflict intensity and political fragmentation.

Since both initial conditions (including severity of conflict and national capacities) and international capacities shape the outcome, there is in effect a tradeoff between them, as Doyle and Sambanis argue there is among the three dimensions of peace building: the greater the initial challenges (hostility and lack of national capacities), the more international resources would be required to attain an equivalent outcome. The tradeoff is not necessarily linear, however. The provision of international resources may affect the provision of national capacities, either positively or negatively. The most effective level and type of international force depends on the extent to which international security forces and their claims of legitimacy crowd in or crowd out—promote or hinder—national security capacity and legitimacy.

These resources include the nature of the mandate and the number of troops, but also the overall legitimacy of the effort and financial resources. In cases where the state has kept paramount control of the means of violence over most of the territory (Guatemala) or where a guerrilla movement wins and captures the state (Uganda, Eritrea), international security provision is unlikely. Opposition or minority groups may want it, but the state can block it, and the state can protect international aid providers. In cases where the control of violence is more divided or fragmented, an international security mandate is likely to be necessary, as argued in the previous chapter. The supply of international security provision, however, depends not only or even primarily on the need but on the degree and nature of interest among those states with the capacity to supply it. Given the limited supply of deployable troops and the limited commitment to many operations, powerful states accept a higher risk of failure in cases of low strategic interest (often in Africa) by providing or paying for fewer troops than needed and insisting on weaker mandates in order to ensure availability of high-quality troops for cases they consider more important to their interests (the Balkans for Europe, Iraq for the United States).

Reluctant troop contributors may argue for lower levels of force on the grounds that international deployments crowd out local capacity. U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld originally argued against expansion of the deployment of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan on the grounds that it might displace efforts to build the Afghan National Army.15 Others argued that broader deployment of an international force with a mandate to demilitarize key political centers (the original mandate of ISAF in the Bonn Agreement) would have supported DDR and created a more favorable environment for creating professional security forces free of factional control. Whereas the latter argument eventually prevailed, with some limits, it appears to remain true that too large a deployment can be counterproductive. SRSG Lakhdar Brahimi’s argument for a “light footprint” in Afghanistan, though directed mainly toward civilian rather than military deployments, was based on opposition to crowding out. Too large a military deployment that appeared to be an invasion or occupation could provoke a backlash that increases insecurity and undermines efforts to create national forces.

Whether international deployments provide security as a public good that strengthens national security capacity depends largely on the domestic legitimacy of the deployment. This legitimacy affects the likelihood that the political actors these forces protect will enjoy sufficient trust and access to build security institutions and the rule of law, if that is their goal. International approval both provides legitimacy, as argued in the previous chapter, and also communicates to opponents of the operation (called “spoilers” by those who support it) that they are less likely to gain external support.

A process endorsed by the UN supposedly enjoys the support of humanity’s global political body and hence should enjoy full legitimacy. Although no body or court has the power to overturn a decision of the UN Security Council, that body is nonetheless political and its structure reflects the undemocratic reality of international power politics. The Bush administration is not alone in believing that its own definition of interest and legitimacy trumps decisions of the Security Council, though the United States is uniquely positioned to implement its defiant views. The United States was able to have the Security Council approve a UN “peace building” operation in Iraq based on an invasion that most members considered illegal. Some cases also involved armed actors who rejected the legitimacy of the intervention or the proposed (or imposed) political settlement, and others (notably Kosovo) also began with interventions not sanctioned by the Security Council. This point is more than a mere footnote: the effectiveness of all security operations and efforts to build security institutions depend on their local and international legitimacy as well as the volume of resources put at their disposal, as a comparison of the effectiveness of the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan illustrates. Because of conflicting goals and values, attempts to legitimate deployments with the national publics of troop-deploying states may conflict with attempts to legitimate those deployments where they take place. In Afghanistan the issue of narcotics exemplifies this problem: the British government has largely legitimated its deployment to southern Afghanistan by telling the British public that the troops are needed there because this region is where the opium poppy that is the source for heroin sold in the UK is grown; but the more these troops engage in direct counternarcotics action, especially crop eradication, the less Afghans will believe that the troops are present to provide for their welfare and security. The case of the Afghan who converted to Christianity posed an even harsher conflict of basic values, as most Afghans appeared to insist that apostasy was a capital crime, while the countries supplying troops and assistance insisted on the basic human right to hold or change religious beliefs.

As the previous chapter notes, international state-building operations begin under conditions where states lack not only the capacity to provide security and services but also legitimacy. Building national capacity for security and legitimate governance is essential to the sustainability of peace.16 The doctrines and organizational practices of these two tasks are usually isolated from each other in different organizations working in parallel but without coordination, although in practice they are closely linked. Building legitimate institutions requires sufficient security for unarmed citizens and nonmilitary officials to participate. Building security institutions requires sufficient legitimacy to motivate participation, risk, and sacrifice. The interim power-sharing agreements that are often needed to start a transition process are just as likely, if not more so, to involve participation in and control over the security forces as participation in and control over the ostensibly authoritative civilian positions.

The standard model for legitimizing international state-building operations is known as “democratic peace building.”17 The predominant view of such operations links this political model to a legal model based on liberal human rights and an economic model based on the market. Therefore the entire package delivered to countries constitutes a “liberal” model of peace building. Elections are the preferred path to establish such legitimacy, but elections can fulfill that function only if certain demanding conditions are met. They require a constitutional process (whether or not the process eventuates in a formal constitution) to establish a broad consensus on the institutions of government and structure of the state to which officials will be elected, as well as on the electoral system and administration. Elections require security against both those who wish to disrupt and discredit them and those who wish to use violence and intimidation to win them. They require both adequate administrative capacity (domestic or international) to ensure that the system is workable, and sufficient agreement on the rules and the mode of enforcement to ensure that losers accept the outcome and winners do not overstep their authority. It is no wonder that first postconflict elections therefore require international security forces and international civilian assistance, except where the incumbents’ legitimacy is established through decisive military victory.

The liberal model, however, has no explicit linkage to the process of state building needed to make the political, legal, and economic institutions meaningful. It also includes no basis of local or national legitimacy other than pure legal and electoral claims, which are generally insufficient to motivate people to sacrifice their lives. The success of SSR requires growing legitimacy of the state and creation of what the previous chapter described as the “esprit de corps” of military officers. Sacrifice usually requires strong religious, nationalist, or group loyalties, which may be more or less compatible with the liberal model but are not contained within or generated by it.18 This model also separates the recognized political process—elections, legislation—from the process of disarming militias and creating or reforming security institutions, as if the latter were an administrative or technical process. A fuller understanding of these operations, however, requires analyzing the politics of interim power sharing and restructuring the forces of violence, which often has greater political consequences than the ostensibly political institutions.

The first stage toward national legitimacy in an internationalized state-building operation is the establishment of an interim administration and agreement on a transition process. Besides a UN transitional administration or a foreign occupation regime, this may take the form of a coalition among national forces pursuant to an agreement or a monitored government consisting of previous incumbents. The main purpose of the transitional government is to preside over a process that establishes a legitimate legal framework for political contestation and rule (generally, a constitution) and to administer the first stages of the implementation of this framework. The transitional government normally must accommodate the claims for inclusion of a variety of parties to the conflict, though in some cases either monitoring of the incumbents or imposition of a UN transitional administration constitutes an alternative.

Establishing a transitional government and implementing a political process often requires protection of international security providers, whether to ensure against defection, to defend the process from its enemies (“spoilers”), or to provide the logistical support needed for the demanding task of holding national elections. Such a protected transitional government can then benefit from international assistance to build its legitimacy and capacity, including the legitimacy and capacity of the national security agencies. International security provision is particularly important in operations that provide for the dismantling or demobilization (DDR) of some forces, as this is likely to generate a security vacuum and heighten tensions. Research indicates that the provision of international security assistance is most needed at the start of the process, while financial aid needs to expand for a considerable period afterward, as national capacity grows.19

Without the separation of politics from violence and the regulation of the latter by law, however, civilian politics and politicians are impotent and the usual power-sharing agreements of limited value. One of the most common complaints from citizens of postconflict societies against international actors is that despite the latter’s rhetoric of peace and democracy they speak mainly with warlords who are the enemies of both, instead of with “civil society.” Depending on the weakness of civilian institutions, it may be more or less possible for international mediators or interveners to engage meaningfully with unarmed political forces. But as long as armed force constitutes the main currency of power, engagement with armed actors, backed up by sufficient international leverage, constitutes the only means to transform their roles. Only the demilitarization of politics makes engagement with nonmilitarized political forces meaningful. The nature of the process for the demilitarization of politics (concentration of the means of violence in the state and the separation of unmediated violence from politics in favor of law enforcement) determines what forces can be engaged. An invasion force can choose its interlocutors, until insurgents blast their way into the political arena. To the extent that DDR and SSR are negotiated with combatants, these combatants become the main interlocutors. The demilitarization of politics is at least as important to the political transition as the holding of elections; the latter are meaningless without the former.

Some states, such as Afghanistan or the Democratic Republic of Congo, have weak civilian institutions and strong armed groups that benefit from foreign aid and/or predation on global markets (narcotics, gold, diamonds, coltan). In such cases, the security forces themselves, not the civilian institutions, constitute the chief arena of competition for power. On several occasions when the interim Afghan government wanted to neutralize the power of regional warlords without openly confronting them, President Karzai appointed them to senior government posts in the capital. By placing these individuals at the head of a largely powerless administration, while separating them from their regionally based armed groups, the government deprived them of power rather than sharing it with them. In doing so it gambled on legitimacy at the expense of capacity.

Building the capacity of security agencies can become technical only to the extent that the agencies are politically neutral and serve a legitimate state and its laws, not political leaders, factions, parties, or ethnic groups. Even in fully consolidated democracies, political struggles continue over the mission, role, financing, and recruitment of the security forces. In a country barely emerging from civil war, the transformation of the institutions of violence and coercion constitutes the main arena for power struggles. Actors devise and evaluate such proposals not on the basis of their technical effectiveness—though they will use such arguments when they seem useful—but on the degree to which they maintain their power and their own security, not necessarily that of a politically neutral, inclusive—and elusive—“public.”

Foreign professionals who specialize in one or the other function may see these tasks as separate, but armed groups, which are the most powerful form of association in postcivil-war situations, pursue political, military, and economic objectives simultaneously. By proposing the separation of these functions into different organizations, the liberal peace-building model threatens to undermine the society’s most powerful individuals and threatens the welfare of their followers, unless local capacities for liberal development grow sufficiently to offer employment and new roles for exercising power and accumulating wealth to the elites that emerged during the war. Such elites may lose from open warfare, but they also stand to lose from consolidated peace, if it means undermining personalistic power. Hence they have a strong interest if not in reversing peace agreements then in resisting their full implementation.

The negotiations over power sharing in the Bonn Agreement, DDR, and SSR in Afghanistan illustrate the centrality of the security sector to politics in postwar state building. At the UN Talks on Afghanistan in Bonn, international actors negotiated a government power-sharing deal with Shura-yi Nazar (the Supervisory Council of the North, the core of the Northern Alliance). The international actors accepted for the time being that faction’s control of all “security” agencies (Ministries of Defense and Interior and the intelligence agency), in return for its agreeing to measures of civilian power sharing. These included accepting a chair of the interim administration (Hamid Karzai) who was not from the Northern Alliance and was not a military commander; sharing civilian ministerial posts with other groups; promising to adhere to a process of gradual broadening of the base of the government, though without specific commitments to give up control of the security agencies; and accepting international monitoring of all these.

Afghanistan’s experience after the Bonn agreement illustrates several political features common to countries experiencing internationalized efforts to build state security forces. Despite frequently agreeing to succumb to civilian political authorities, armed factions (including government armed forces) often fortify parallel or preexisting command or authority structures to weaken the actual power of nominal civilian control. The Northern Alliance, for instance, accepted civilian power sharing but resisted measures to dilute its control of the security organs or to disempower armed commanders.

Similarly, armed factions whose commanders are reluctant to relinquish control over their soldiers commonly employ such tactics as formal delays, footdragging, efforts to interpret or rewrite agreed-on depoliticization of security forces, and outright duplicity. Consider the negotiations over the composition and powers of the new Afghan National Army. These largely secret negotiations, which occurred in Kabul in 2002–03, mainly involved UNAMA [the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan], the United States, a few members of the Afghan government, and the Shura-yi Nazar leadership of MoD. The latter, led by Marshall Fahim, demanded full pay for the clearly exaggerated figure of two hundred thousand militia members (even after settling on one hundred thousand, many turned out to be phantoms). It also asked for a permanent army of the same size and insisted that the officer corps and rank and file of the new army come mainly from former members of mujahidin units. These demands would have ensured domination of the state by these armed groups, whatever civilian “power-sharing” measures were introduced. In the end, the Karzai administration and international allies were able to overcome most of these early efforts to undermine security sector reforms.20 They did so not through simply formal or technocratic responses but via the deployment of capital and limited coercion, as well as the legitimacy that internal and external recognition offered warlords.

Reform of the leadership of the main security institutions in Afghanistan illustrates how these politically sensitive appointments respond to a political context more than to technical needs of SSR, and that such political criteria are not necessarily misplaced. Changing the Afghan ministers of defense and interior and the chief of intelligence, as well as key staff in each ministry, required difficult political decisions, which threatened violent fallout in every case. These changes were closely associated with key political events: the minister of the interior was changed at the Emergency Loya Jirga, the chief of intelligence was changed after the Constitutional Loya Jirga, and the minister of defense was changed as a result of the first presidential election.

The warlords accepted these appointments in Kabul in large part because of pressure from the U.S.-led coalition, whose support they needed to protect them from the Taliban and other enemies. In this case the judicious application of internationally supplied coercive resources provided the government with the opportunity to build the state by ending the capture of administration by informal power holders. The same changes had the potential to increase the legitimacy of the government, if it could deliver better than the warlords, and to increase the government’s fiscal base, as it took direct control of major customs points. The removal of Fahim as minister of defense encouraged many commanders to demobilize and increased the supply of recruits to the ANA. These are examples of the political use of international forces in support of state building.

Political interest affects the definition of security objectives and hence priorities among the security tasks. International interests focus on challenges to international security, and international action therefore concentrates on military institutions, often equating building a large army with building “security.” Often, interveners continue to treat the aftermath of a civil war as largely a military security problem, whereas the end of warfare often creates new security problems, such as crime and economic predation.21

In Afghanistan there was from the start a contradiction between the security objectives of the United States and the security imperatives of state building and the political process. The United States and its coalition partners intervened in Afghanistan to protect their own security from al-Qaeda, not to protect Afghans from al-Qaeda, Taliban, the Northern Alliance, militias, drought, poverty, and debt bondage to drug traffickers. The military strategy for accomplishing the former objective was to dislodge the Taliban and al-Qaeda with air strikes while using the CIA and Special Forces to equip, fund, and deploy the Northern Alliance and other commanders to take and hold ground, including cities. Although the United States halfheartedly tried to prevent the Northern Alliance from seizing the capital, it inevitably did so, as the United States was not prepared to occupy Kabul itself anymore than it was later prepared to provide security in Baghdad.

The Bonn Talks therefore had to deal with the task of preventing the victorious militias from looting, fighting with each other, and seizing power. The International Security Assistance Force emerged as a coping mechanism, if not quite a solution. Through an act of diplomatic ventriloquism by the UN team, the parties to the Bonn Agreement asked the Security Council to authorize deployment of a “United Nations mandated force to assist in the maintenance of security for Kabul and its surrounding areas.” The agreement went on to note, “Such a force could, as appropriate, be progressively expanded to other urban centres and other areas.” The participants in the talks also agreed “to withdraw all military units from Kabul and other urban centers or other areas in which the UN mandated force is deployed.” This UN-mandated force became known as the ISAF. Since August 2003 it has been under the command of NATO. Neither the withdrawal of militias from Kabul city nor the expansion of ISAF to provinces began until then, largely because of opposition from the U.S. Department of Defense, which wanted to ensure priority for its war-fighting goals over the internal security goals of ISAF.

The same hierarchy of priorities among security goals led to the establishment of the “lead-donor” system for SSR, which delayed progress and blocked coordination. As the United States initially wanted to devote resources solely to the “counterterrorist” operation, it took on responsibility for building the new Afghan National Army, while asking other Group of Eight (G8) countries to take on DDR, police, justice, and counternarcotics. The Afghanistan Compact finally jettisoned this system after the United States and others realized, in the words of the compact, that “Security cannot be provided by military means alone. It requires good governance, justice and the rule of law, reinforced by reconstruction and development.”

The specific circumstances of the intervention in Afghanistan, in particular the presence of a direct threat to the United States, intensified the contradiction between different security goals and means, but similar problems exist elsewhere. Nationals of the postconflict country often oppose the focus on armies and elections and ask for more efforts to be devoted to rule of law, human rights, justice, police, parties, and civil society.22 These institutions would provide ordinary citizens with more security and genuine representation. They would make elections more meaningful in a way that building an army cannot. Charles Taylor was able to win a presidential election in Liberia in 1997 largely because of his control of extralegal “security” institutions, which enabled him to intimidate the electorate. Former Liberian President Amos Sawyer has argued that the international community’s focus on building an army for Liberia did little to improve the security of Liberians, who associate an army with insecurity rather than security. They were in much greater need of police and a justice system.23

Partly this results from international actors doing what they know how to do rather than what needs to be done. Military institutions are easier to build with external aid than police, justice, and legal institutions, because military violence depends less on local knowledge and legal and social norms.24 Previous analyses, however, have demonstrated the close interrelationship within the security sector of military and police reform, and the need for police reform to be coordinated with legal, judicial, and penal reform.25

If building security institutions, separating military from civilian roles, and strengthening civilian institutions and the rule of law are necessary conditions for electoral politics to meaningfully arbitrate among contenders for power, does state building, or building basic local capacities for security or economic development, have to take primacy over holding elections or building other democratic institutions? Analyses of past operations suggest that holding elections before DDR, at least, can reignite conflict and be more likely to lead to destabilization, since the elections can be viewed as winner take all.26

Some have posed the question in terms of sequencing or priorities. International operations are too short and lack the long-term commitment (in time, mandate, or resources) needed to implement sustainable transformation of political structures and state building. One study found that the single variable that best explained success in “nation building” operations was the length of international engagement.27 Providing security—including the demobilization of nonstate armed groups, the disempowering of abusive groups that came to power through violence, the reform of official coercive capacities so that they enforce the rule of law rather than factional or personal interest or political agendas, and the building of new security agencies and administrative capacity—must precede elections and the broad political mobilization over conflictual issues that elections stimulate.

Marina Ottaway, challenging the viability of the democratic peace-building model in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, and other fragile states, has advocated initial focus on core issues of security and state control, going so far as to oppose international pressure even to form a central state in Afghanistan, let alone a democratic one. A number of other analysts have argued that the emphasis on democracy is premature or misplaced. Jack Snyder and Edward Mansfield argue that elections often generate more conflict. Francis Fukuyama and Fareed Zakaria, in works on state building and illiberal democracy, argue that rule of law and basic institutions of governance must precede the development of institutions for contestation of power.28

Some practitioners echo these cautions. In a series of speeches, Lakhdar Brahimi has argued that UN operations are expected to accomplish a complete agenda of political, social, and economic transformation in some of the world’s poorest and most violent countries on a tight schedule and with few resources.29 Pressure for elections, transitional justice, accountability for human rights violations, and social reforms (notably in the status for women) builds early, as a result of the commitments of donor governments and NGOs, as well as the high expectations of the beneficiary population. UN political officers often find that these pressures fail to take into account the time needed for basic social transformation, the difficulty (not to say impossibility) of social engineering according to a timetable, the unforeseeable consequences of or backlash from such engineering in divided societies, and the amount of resources needed to build the institutional capacity to implement such changes.

The burst of effort at the start of an operation and the mobilization of international actors with short-term time horizons fail to build local capacity or the basic institutions needed for sustainable peace, while focusing efforts on visible benchmarks such as elections. Elections may accentuate differences and stimulate conflict before the society and state have the capacity to manage them. These capacities include both the institutional strength of rule-of-law institutions and the social capital of trust, built through postconflict reconciliation and cooperation in economic recovery.

Brahimi, in a “nonpaper” that he circulated to the diplomatic community before leaving Afghanistan at the beginning of 2004, noted that provision of security, economic reconstruction, and national reconciliation had not kept pace with the political timetable. As the international community prepared to help Afghanistan hold elections, there was still no rule of law, the means of violence were still under the control of numerous armed groups, and there was still a gulf of mistrust among various groups. Nor had economic development and service delivery taken off enough to build the capacity of the state, bind people’s loyalties to it, or provide alternative livelihoods to those involved in armed groups or the drug economy.

But even though not everything can be done at once with inadequate resources, sequencing alone is too simple a model to capture the relationship between security and political reform or democratization. There is often a mutually interdependent relationship between security and political legitimacy that makes it difficult to separate these functions in a temporal sequence. The international operation must be sufficiently legitimate that its protection helps to legitimate rather than delegitimate the transitional administration. This internationally provided transitional security is necessary for building the legitimacy of government institutions through participation and increasing the government’s capacity to mobilize resources and deliver services through the state. Only governments enjoying a significant degree of legitimacy can build sustainable national capacity to deliver security.

Both commanders and ordinary combatants (including part-time combatants) also need an economy that can sustain them without recourse to armed predation. Security provision and the rule of law are also necessary for building state capacity and enabling the state to provide the needed environment for economic growth. International security provision may be necessary to protect and support the initial processes of state fiscal reform. The Ministry of Finance in Afghanistan was able to operate with some autonomy from the armed groups in the Ministry of Defense only because of the presence of ISAF and the coalition, which provided its personnel with a margin of security.30 This security was essential to enable it to bargain from a position of confidence with the Ministry of Defense over the integrity of the payroll. These negotiations permitted DDR to proceed. The international protection extended to the central government by ISAF also made it possible to maintain the integrity of the Da Afghanistan Bank (the central bank) and enabled the Ministry of Finance to overcome strong resistance and centralize revenue in a single treasury account. Without these measures, the Ministry of Defense and other factionally controlled armed forces could have intimidated, threatened, or even attacked the officials leading the reform, ensuring that systems that facilitated the capture of state revenues and payments by factions remained in place.

Once it had reformed its internal operations, the Ministry of Finance sought further assistance from the international security forces to help it gain control of customs points and provincial branches of state banks. Such control is essential if the national government put in place by the Bonn Agreement and now functioning under an elected president is to gain control of payments in the provinces and receive the revenues from import duties. The international forces, however, failed to see these as part of their mission, which left major obstacles to state building in place. Such control of state revenues and payment systems is necessary to enable the state to establish and operate police, courts, and other institutions of the rule of law that can create the security of contract and operations that according to the liberal model will encourage investment, marketing, and economic development.

This analysis indicates that even though there is no simple formula for sequencing, there is a hierarchy of priorities. An international peace-building or stabilization operation must take as its first priority providing whatever transitional security assistance is needed to enable a transitional government to start the process of legitimizing state power. To do so, that operation must itself be legitimate. The negotiation of the security transition is as important to the success of the operation as (if not more important than) the negotiation of what is usually called the “political” transition, which bears mainly on civilian authorities. The successful and mutually reinforcing action of international security provision and national legitimacy may then make it possible to build national capacity for domestic provision of security. Both international and domestic security provision can assist a legitimate government to build its capacity to provide other services, needed for the welfare and security of the people and the growth of the economy.

1. United Nations, Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Actions of the United Nations During the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, UN Doc. S/1999/1257 (1999); United Nations, Statement by the Secretary-General on Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Actions of the United Nations During the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, UN Doc. SG/SM/7263 (1999); United Nations, Report of the Secretary-General Pursuant to General Assembly Resolution 53/35: The Fall of Srebrenica, UN Doc. A/54/549 (1999).

2. Stephen John Stedman, “Spoiler Problems in Peace Processes,” International Security 22, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 5–53; United Nations, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (Brahimi Report), UN Doc. A/55/305-S/2000/809 (2000).

3. On Afghanistan, see Michael Bhatia, Kevin Lanigan, and Philip Wilkinson, “Minimal Investments, Minimal Results: The Failure of Security Policy in Afghanistan,” Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Briefing Paper, June 2004; James Dobbins et al., America’s Role in Nation-Building: From Germany to Iraq (Santa Monica: RAND, 2003); Seth G. Jones, “Averting Failure in Afghanistan,” Survival 48, no. 1 (Spring 2006): 111–28.

4. Robert H. Jackson and Carl G. Rosberg, “Why Africa’s Weak States Persist: The Empirical and the Juridical in Statehood,” World Politics 35, no. 1 (October 1982): 1–24. See also Michael Barnett, “The New United Nations Politics of Peace: From Juridical Sovereignty to Empirical Sovereignty,” Global Governance 1, no. 1 (Winter 1995): 79–97.

5. Classifying operations in one or another category can itself be a political claim. A term such as “peace building” contains an implicit claim of legitimacy, since the goal is defined as “peace,” a pure public good, rather than as reducing the level of violent contestation against a particular (and perhaps unjust) distribution of power and wealth. Different but related claims pertain to “postconflict” and “stabilization,” for example.

6. Doyle and Sambanis analyze the success of UN peace operations (defined as nonreversion to collective violence plus minimal democratization) using indicators of conflict intensity, national capacities, and international capacities (see Michael W. Doyle and Nicholas Sambanis, “International Peacebuilding: A Theoretical and Quantitative Analysis,” American Political Science Review 94, no. 4, Dec. 2000, 779–801). This chapter suggests a theoretical basis for further conceptualizing and measuring those capacities, both national and international, and their interaction.

7. James Boyce, introduction to James K. Boyce and Madalene O’Donnell, eds., Peace and the Public Purse: Economic Policies for Postwar Statebuilding (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2007).

8. Ghassan Salamé, Appels d’Empire. Ingérences et Résistances à l’âge de la mondialisation (Paris: Fayard, 1996).

9. Barbara F. Walter and Jack Snyder, eds., Civil Wars, Insecurity, and Intervention (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999). See also Leonard Wantchekon, “The Paradox of ‘Warlord’ Democracy: A Theoretical Investigation,” American Political Science Review 98, no. 1 (2004): 17–33.

10. See note 1.

11. See Supplement to an Agenda for Peace: Position Paper of the Secretary-General on the Occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the United Nations, Report of the Secretary-General on the Work of the Organization, UN Doc. A/50/60-S/1995/1, January 3, 1995; and United Nations, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (Brahimi Report).

12. Anthony Giddens, The Nation-State and Violence, vol. 2, A Contemporary Critique of Historical Materialism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

13. Of course these cases are most similar to decolonization, in which the UN played a major role, though not in exercising trusteeships or international transitional administrations as in these cases. The challenge of transforming colonies into sovereign states has proved to be a difficult one.

14. Doyle and Sambanis, “International Peacebuilding.”

15. Henry L. Stimson Center, “Views on Security in Afghanistan: Selected Quotes and Statements by U.S. and International Leaders,” Peace Operations Factsheet Series, June 2002.

16. Doyle and Sambanis, “International Peacebuilding.”

17. Marina Ottaway and Anatol Lieven, “Rebuilding Afghanistan: Fantasy Versus Reality,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Policy Brief 12 (2002): 1–7; Ottaway, “One Country, Two Plans,” Foreign Policy 137 (2003): 55–59; Ottaway, “Nation Building,” Foreign Policy 132 (Sep.–Oct. 2002): 16–24; Roland Paris, At War’s End: Building Peace After Civil Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004).

18. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 2006).

19. Paul Collier, with V. L. Elliott, Havard Hegre, Anke Hoeffler, Marta Reynal-Querol, and Nicholas Sambanis, Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003).

20. Instead, the total to be demobilized turned out to be closer to sixty thousand; the ultimate strength of the armed forces is now planned to be forty to seventy thousand, which some think is still larger than the country needs or can afford; and fewer than 2 percent of the Afghan National Army’s recruits are former mujahidin. The latter have been largely accommodated in the police, where their continuing ties of group solidarity undermine attempts at reform.

21. Charles T. Call, “Conclusion,” in Constructing Justice and Security After War (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2007), 25–27.

22. Amos Sawyer, comment during Center on International Cooperation and International Peace Academy Conference on Post-Conflict Transitions: National Experience and International Reform, New York, March 28, 2005.

23. Ibid.

24. Francis Fukuyama, State-Building (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004). In his book, Fukuyama argues that some institutions are easier to transfer to new environments because the requirements for them to be successful are more general, since they function in more or less the same way everywhere. The central bank and the military are cited as examples of this, whereas other institutions, such as a judicial system, are more dependent on local norms and embedded practical knowledge.

25. The Brahimi Report, for instance, suggested measures to ensure that UN transitional administrations are able to adopt an off-the-shelf legal system devised for such situations. See United Nations, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (Brahimi Report).

26. Chester A. Crocker, “Peacemaking and Mediation: Dynamics of a Changing Field,” Coping with Crisis: Working Paper Series, International Peace Academy (March 2007); Simon Chesterman, Michael Ignatieff, and Ramesh Thakur, “Making States Work: From State Failure to State-Building,” International Peace Academy/United Nations University (July 2004); International Peace Academy/Center on International Cooperation, “Post-Conflict Transitions: National Experience and International Reform,” Meeting Summary, Century Association, New York, March 28, 2005.

27. Dobbins et al., America’s Role in Nation-Building.

28. Fukuyama, State-Building (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004); Edward D. Mansfield and Jack Snyder, “Democratic Transitions and War: From Napoleon to the Millenium’s End,” in Turbulent Peace: The Challenges of Managing International Conflict, ed. Chester A. Crocker, Fen Osler Hampson, and Pamela R. Aall (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2001), 113–26; Fareed Zakaria, The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad (New York: Norton, 2003).

29. See United Nations, Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (Brahimi Report).

30. Ashraf Ghani, Clare Lockhart, Nargis Nehan, and Baqer Massoud, “The Budget as the Linchpin of the State: Lessons from Afghanistan,” in Peace and the Public Purse: Economic Policies for Postwar Statebuilding, ed. James K. Boyce and Madalene O’Donnell (Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2007), 153–83.