Prospects for Improved Stability Reference Document

Since the overthrow of the Taliban by the U.S.-led coalition and the inauguration of the Interim Authority based on the UN-mediated Bonn Agreement of December 5, 2001, Afghanistan has progressed substantially toward stability. Not all trends are positive, however. Afghanistan has become more dependent on narcotics production and trafficking than any country in the world. It remains one of the world’s most impoverished and conflict-prone states, where only a substantial international presence prevents a return to war. The modest results reflect the modest resources that donor and troop-contributing states have invested in it. Afghans and those supporting their efforts have many achievements to their credit, but declarations of success are premature. The establishment of the major institutions required by the Constitution of 2004 will constitute the end of the implementation of the Bonn Agreement. That agreement on transitional governmental institutions, pending the reestablishment of permanent constitutional governance, was drafted and signed at the UN Talks on Afghanistan in Germany in November–December 2001. The election of the lower house of parliament (Wolesi Jirga) and provincial councils, now set for September 18, 2005, will mark the end of that transitional process, though only with a bit of constitutional stretching. Elections to district councils, needed to elect part of the Meshrano Jirga (upper house of the National Assembly), cannot be held in 2005, and the government will therefore establish a truncated upper house. [The parliamentary and provincial council elections were held as scheduled. At date of publication, district council elections have not been held.]

The establishment of elected institutions hardly constitutes the end of Afghanistan’s transition toward stability. The long-term strategic objective of the joint international-Afghan project is the building of a legitimate, effective, and accountable state. State building requires balanced and mutually reinforcing efforts to establish legitimacy, security, and an economic base for both. Thus far internationally funded efforts to establish legitimacy through a political process (the only mandatory part of the Bonn Agreement) have outpaced efforts to establish security and a sustainable economic base. The next strategic objective must be to accelerate the growth of government capacity and the legitimate economy to provide Afghans with superior alternatives to relying on patronage from commanders, the opium economy, and the international presence for security, livelihoods, and services.

Afghanistan will not be able to sustain the current configuration of institutions built with foreign assistance in the foreseeable future. Given current salary levels and future staffing plans, maintaining the Afghan National Army will eventually impose a recurrent cost estimated at about $1 billion per year on the Afghan government. This is equivalent to about 40 percent of the estimated revenue from narcotics in 2004. In order for Afghanistan to cover the cost of the ANA with 4 percent of legal GDP (near the upper limit of the global range of defense spending), it would have to more than quintuple its legal economy. The constitution requires Afghanistan to hold presidential elections every five years, Wolesi Jirga elections every five years, provincial council elections every four years, and district council elections every three years. This works out to between eight and ten nationwide elections every decade, depending on whether presidential and WJ elections are concurrent. Currently each election (including voter registration) costs international donors more than $100 million, which is equivalent to 40 percent of the government’s current yearly domestic revenue. Hence the current efforts risk leaving Afghanistan with elections it cannot afford and a well-trained and well-equipped army that it cannot pay. Projecting the results of such a situation does not require sophisticated analytic techniques.

The end of the implementation of the Bonn accord should thus constitute a benchmark for the renewal of international commitment, rather than the declaration of success and the start of disengagement. The entire range of international actors in Afghanistan needs to publicly recommit themselves to support an Afghan-owned and led process. The UN Security Council has extended the mandate of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) until March 24, 2006. The resolution identified the main future tasks in Afghanistan as holding free and fair parliamentary elections; combating narcotics; completing the demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration of armed groups; continuing to build Afghan security forces; continuing to combat terrorism; strengthening the justice system; protecting human rights; accelerating economic growth to ensure that reforms are sustainable; and fostering regional cooperation.1

The coalition has moved from a war-fighting mandate toward one of stabilization through the establishment of Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) and an “allegiance program” to reintegrate returning Taliban. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), having assumed command of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), has also established PRTs in a growing number of provinces and is considering a U.S. proposal for unification of CFC-A and ISAF under a joint NATO command with a common mission focused on stabilization. International financial institutions, the United States, the European Union, and other donor governments have responded with growing rather than shrinking commitments to reconstruction, largely in response to the coherent and farsighted plan proposed by the Afghan government in its report Securing Afghanistan’s Future,2 presented to the Berlin Conference on March 31–April 1, 2004. Some have suggested reaffirming commitment to all of these goals through a “Kabul process,” culminating in an international conference hosted by Afghanistan to establish the framework for political, military, and economic support beyond the Bonn Agreement.

This document reaches these conclusions by using the Stability Assessment Framework methodology developed by the Clingendael institute (The Hague) to help governments and other institutions plan assistance to countries at risk of conflict.3 The document first presents qualitative assessments of the trends and levels of key indicators since the establishment of the Interim Authority. These indicators, which comparative research has shown to provide early warning of violent conflict, include political, economic, and social factors.

Understanding these indicators requires what F. Scott Fitzgerald called “the test of a first-rate intelligence”: “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” One must evacuate both indicators’ level and their trend or direction of change. The levels of indicators in Afghanistan place it among the world’s most unstable, destitute, and conflict-prone countries, while many trends are positive. Trends that are not clearly positive, such as the size of income and assets derived from narcotics trafficking, the security of Afghan civilians and property rights, corruption, and the quality of local governance, require focused attention.

After presenting the indicators, the analysis assesses the capacity and legitimacy of institutions necessary to provide stable governance. These include the key institutions of government, especially those for security and the rule of law, as well as those that finance its operations. These institutions are constituted by actors, whose orientations, strategies, and resources the paper examines next. It starts with national actors and continues with the international actors present in Afghanistan. Long experience of violence and instability makes Afghan and regional actors reluctant to invest their assets fully in strategies on the basis of expectations of stability, but the longer change for the better persists, the more actors will gradually adjust their strategies toward stabilization. Any change in expectations remains fragile.

Finally, the paper presents policy recommendations to redress the gaps revealed by the foregoing analysis.

Figure 13.1 The Informal Equilibrium. Source: World Bank, Afghanistan—State Building, Sustaining Growth, and Reducing Poverty: A Country Economic Report, 2005, p. xi.

Until the shock of September 11, 2001, and the international response it provoked, the situation in Afghanistan, as in many states undergoing crises of governance, could be characterized as what the World Bank has called an “informal equilibrium” at low levels of development and security. (See Figure 13.1.) Insecurity and lack of infrastructure, due to both lack of investment and wartime destruction of assets, combined with pressure on scarce economic and natural resources, favored the development of criminalized economic activities, especially those fueled by demand in the developed countries. These activities funded, as they still do, illicit organized violence (warlordism and terrorism), which also derive their resources, especially weapons, from more developed countries. This dark side of globalization hinders attempts to constitute accountable, lawful governance. The consequent lack of security discourages licit investment, reinforcing the vicious circle of poverty, integration into global organized crime, and violence.

Moving from this harmful equilibrium to a virtuous circle where security and legitimate development reinforce each other to promote both the rule of law and the growth of productive global economic opportunities requires balanced efforts to transform the political, economic, and social factors, as well as the international environment, in a positive direction. Although such efforts are under way, Afghanistan is still far from the “formal equilibrium” that characterizes stabler, more economically developed societies (Figure 13.2).4

This section evaluates the key elements of Afghanistan’s vicious circle to estimate how far the country has moved away from that equilibrium in the past three years. Figure 13.3 lists the twelve indicators. This report groups the indicators in four categories: governance, economy, social pressures, and international environment. Indicators of the state of governance include (1) the legitimacy of the state, (2) the delivery of public services, (3) the rule of law and human rights, (4) the coherence of the political elite, and (5) the performance of the security apparatus. Indicators of economic performance include (6) the general state of the economy and (7) the relative economic positions of groups. Indicators of social pressures include (8) demographic and environmental pressures, (9) migration (including brain drain), (10) displacement, and (11) groupbased hostilities. Finally this section examines (12) Afghanistan’s international environment.

Figure 13.2 The Formal Equilibrium. Source: World Bank, Afghanistan—State Building, Sustaining Growth, and Reducing Poverty: A Country Economic Report, 2005, p. xi.

Figure 13.3 List of Indicators for Stability Assessment Framework.

During the past quarter century, the legitimacy of the state in Afghanistan fell to an all-time low. Since the installation of the Interim Authority of Afghanistan on December 22, 2001, however, it has gained a diffuse legitimacy, based on its stated goals, increasing representativeness, adoption of a constitution, and holding of the first presidential election in Afghan history. This diffuse legitimacy is not yet supported by legitimacy based on performance, as the delivery of public services falls far short of popular demands and expectations.

Reinforcing the state’s legitimacy faces a daunting contradiction and is interrelated with all other aspects of state building. Without steps to eliminate the narcotics trade, which the UN estimates equaled 60 percent of the legal and hence 40 percent of the total economy in 2004–05, the government cannot implement the rule of law, diminish corruption, gain control over its local appointees, and curb illicit power holders. Yet the state cannot increase its legitimacy while destroying nearly half of the country’s economy with foreign military assistance.5 Securing Afghanistan’s Future estimated that growth in the legal economy would have to average 9 percent per year for more than a decade in order to draw people out of the drug economy while supporting the institutions needed for the rule of law. The IMF projects growth for 2004–05 as falling below that level.

The Bonn Agreement outlined a process to build the legitimacy of an initially unrepresentative government. The Afghan authorities have met the benchmarks of that process. The Emergency Loya Jirga of June 2002 inaugurated a broadening of power beyond the armed groups aided by the United States and the coalition to fight the Taliban and al-Qaeda. The subsequent constitutional process led to the loya jirga that convened in December 2003 and approved a new constitution on January 4, 2004. The electoral registration and subsequent election of the president, on October 9, 2004, showed the strong desire of Afghans to participate in the new system of government.

Currently, Afghans appear to support the idea of a strong, central state, mainly to protect them from decentralized armed groups. Surveys show that an overwhelming majority (88 percent) of Afghans of all regions and ethnic groups call for the central government to end the rule of gunmen.6 Nonetheless consensus on how to organize that order remains fragile. The Constitutional Loya Jirga exposed a significant ethnic divide, as did the results of the presidential election. One opponent of state centralization describes the circles of power as “the handpicked Karzai and his small circle of Western-educated Pashtun technocrats.7 The “Pashtun technocrats” deny that their ethnic background determines their state-building strategy and ask to be judged on their performance for the whole nation. The country’s history of mistrust, personalized politics, and political exclusion places a heavy burden on officials to prove that they are acting as legitimate state leaders rather than dispensers of ethnic or political patronage. Given the weakness of institutions and the lack of trust within the political elite, demands for inclusion are often posed in ethnic rather than political or merit-based terms.

The state does not yet have the capacity to sustain itself without foreign military and financial support, though, as shown below, that small capacity is growing. The forces that might undermine the state are less ideological opposition than factors fueled by the population’s pervasive insecurity and destitution, as well as Afghanistan’s continuing vulnerability to international destabilization. Most leaders accept that the current process of stabilization is better than a return to civil war, but the state could not yet mitigate the security dilemma that militias and their supporters in neighboring countries would face in the absence of the international presence, or if that presence turned destabilizing.

The government has started to improve the delivery of public services, but it has a long way to go before meeting minimal standards or people’s expectations

Security

Some Afghans say that their security has improved, but they overwhelmingly cite it as their principal problem.8 The peaceful conduct of the presidential elections was a milestone in the reestablishment of security, but that resulted in 2004 from uniquely intense, temporary international efforts.

Different actors define security differently. The coalition measures it as security from attacks by insurgents. Coalition spokesmen claim that as a result of military campaigns, changes in Pakistan’s behavior, and the offer to reintegrate Taliban, this threat has decreased, though it continues.9

The UN and aid community focus on attacks on aid workers, which have increased. Preliminary data collected by the Center on International Cooperation show that the number of “major incidents” (killings, kidnappings, ambushes, landmines, and other injuries due to violence) affecting humanitarian workers in Afghanistan increased from none under the Taliban in 2001 to four, ten, and then sixteen in the three following years. Data collected by the Afghan NGO Security Office (ANSO) on killings of all NGO staff shows thirteen killed in 2003 and twenty-one killed in January–August 2004, many of them in connection with election preparation rather than humanitarian work.

Afghans cite the general state of impunity exploited by commanders, not the Taliban or al-Qaeda, as the main source of insecurity, and they see establishment of the rule of law and disarmament as the solution. Many militias have been disbanded, but some claim that DDR has increased insecurity, especially in northern Afghanistan, as the former fighters have retained their personal weapons and are not reintegrated, and the new security institutions are not yet effective. Afghans also cite violent crime in the south and southeast as having increased since the defeat of the Taliban.10

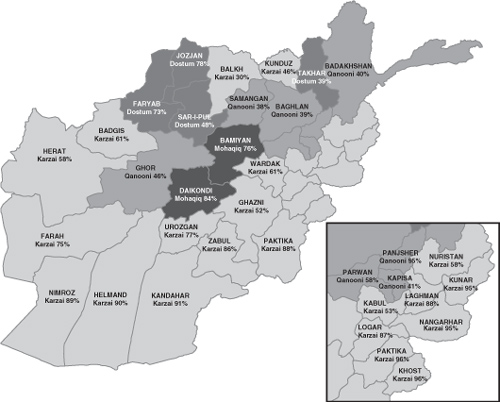

The differing definitions of security on the part of the Afghans and internationals in Afghanistan result in very different perceptions of which parts of the country are more secure. Figure 13.4 compares the map of security incidents distributed by the UN with a map based on a survey of Afghan perceptions. It shows that international actors consider the Pashtun areas, where Taliban are active, as the main source of insecurity, while Afghans living in those areas actually feel more secure than those living in the northern and western parts of the country, where people report more factional fighting and property disputes.11

Figure 13.4a Map of Security as reported by U.N.

Figure 13.4b Map of Security as Perceived by Rural Afghans.

A major source of insecurity cited by Afghans is the capture of local administration by commanders. In March 2005 demonstrators demanded the removal of corrupt and abusive local authorities in both Mazar-i Sharif and Kandahar.12 Although hard data are lacking, many observers have the impression that, even if cabinet appointments have improved, most of the government’s provincial appointments and a larger number of district and local appointments constitute de facto legitimation of control by commanders. Afghans have not seen the clear improvement in security that they hoped for.

Public Revenue and Budget

The abilities of the state to plan and manage expenditure and to raise revenue are a precondition for all other areas of public services. The Afghan state must contend not only with the legacy of a historically weak state and decades of war but also with a dual public sector. Most international aid and hence most public expenditure does not go through the government budget or any mechanism controlled by the Afghan authorities, but rather through a separate international public sector established in Afghanistan by donors and contracting by international actors on the ground, especially the coalition. Unlike national public expenditure, which is accounted for by the budget process and, after reform, paid from a single treasury account, international public expenditure is not subject to any comparable control by an authority that can be held accountable. It is administered by dozens of donors, international agencies, contractors, and implementing organizations, all of which have their own financial systems, accounts, and reporting procedures.

The Afghan government has introduced mechanisms, such as the Afghanistan Development Forum and the Consultative Groups, to introduce some order into donor expenditure, but these rely on voluntary compliance and reporting. Coalition contracting is not subject to even this oversight. The international public sector is not subject to taxation and competes with the national one for funding and personnel. Whereas the establishment of the dual public sector constitutes an understandable short-term response to the lack of capacity of the Afghan national public sector, it develops vested interests in its own perpetuation that threaten the development of the Afghan national capacity that is essential for stability and political accountability.

The difference between positive trends and a very low level of indicators is evident in the fiscal development of the national public sector. Former Minister of Finance Ashraf Ghani instituted a budgetary process as the main instrument of policy, centralized revenue in a single treasury account, reformed and simplified customs, and gained increasing control of revenues captured by commanders. His successor is continuing the process of reform. Afghanistan has adhered to an IMF staff-monitored program (SMP) since 2002. It has exceeded all of the IMF revenue targets, though the government’s internal targets were higher. Securing Afghanistan’s Future laid out a scenario for raising government domestic revenue to $1.5 billion per year in five years, though this required a level of interim budgetary support that donors have not supplied. The government did not meet the SMP expenditure targets in 2004–05 because of a decision to curtail excessive expenditure before the presidential elections. The delay in appointing the cabinet extended what was intended as a short-term measure.

Despite resource mobilization efforts, Afghanistan’s ability to raise revenue is still far less than that even of a poor neighbor such as Pakistan, as shown in Figure 13.5. The annual domestic revenue of the Afghan state currently stands at 4.5 percent of GDP, while both Pakistan and Thailand (low-income and lowermiddle-income Asian states) are able to mobilize 16–17 percent of their GDP. Hence the domestic revenue of the Afghan state, the cost of services it can provide from its own resources without foreign aid, amounts to less than $11 per capita per year.13 Furthermore, as long as the cash economy depends on tax-free international aid and illegal narcotics, the government will be able to tax most of the cash economy only indirectly. The government has tried to capture some of the income generated through import duties and by levying a new tax on high housing rents in Kabul.

Figure 13.5 Fiscal Capacity of the Afghan State in Indexed Comparison (Afghanistan = 100) to an Asian Low-Income Country (Pakistan) and an Asian Low-Middle Income Country (Thailand).

These figures do not reflect the ability of Afghans to pay taxes, however. These figures include only the funds that are deposited into the single treasury account. Afghans pay substantially more taxes. Some are “legal” taxes that are retained by local power holders. Some power holders have also imposed their own taxes and fees. General Dostum, for instance, collects a capitation fee (head tax) through local mosques in the provinces under his control, though there is no basis for this tax in national law. Hence the government could substantially raise revenue while actually decreasing the current tax burden on the people by coordinating security and revenue policies.

The government has developed one mechanism to deliver public goods to communities while bypassing the public expenditure system: the National Solidarity Program (NSP). This program offers up to $20,000 in block grants to villages. The villages must elect representative councils, including women, and agree on a development project to be financed with NSP funds and implemented by the village. The government has contracted with NGOs and international agencies to assist the councils in planning and to deliver and monitor the expenditure. Government officials claim that this program has been successful in making villagers feel like citizens of the country again by establishing direct links to the central government. In addition, by encouraging the villagers to achieve consensus and implement projects, it builds social capital for development, rather than fragmenting society to ensure state predominance, as in the past. Government critics claim that NSP has established a patronage network to build political support for the government, which it is not always easy to distinguish from the legitimacy of the state.

Monetary Management

The Bonn Agreement mandated a reform of the central bank (Da Afghanistan Bank, DAB), which introduced a new currency at the end of 2002. The new currency, redenominated after decades of hyperinflation, has remained stable or appreciated, largely thanks to foreign exchange reserves earned through narcotics exports, remittances, aid, and the operating expenditures of foreign organizations in Afghanistan. Transaction costs have consequently decreased, and prices have stabilized relative to past hyperinflation.14 The appreciation of the exchange rate may be due to the “Dutch disease” resulting from foreign expenditures and a single-crop (opium) economy, pricing other exports out of the market.

Most payments, including within the government, are still carried out in cash. Some international banks have opened branches in Kabul, but their high fees and minimum balance requirements, combined with the continuing nonconsumer orientation of DAB, means that modern banking services are not available to the public, which relies on the hawala system for payments, transfers, and remittances. Reform of the state banking system is also lagging.

Under the Taliban in 2000, only 32 percent of Afghan school-aged children and only 3 percent of Afghan girls were reported to be enrolled in school.15 Reported school registration in Afghanistan is now at record highs for both boys and girls, passing four million children, one-third of them girls, in 2003. UNICEF now estimates school attendance at 56 percent.

These trends are positive, but Afghanistan’s National Human Development Report, released in February 2005, stated that Afghanistan still has “the worst educational system in the world.”16 Buildings and equipment are still lacking, the quality of teaching is low, and fewer than 15 percent of teachers have professional credentials.17 Afghanistan’s literacy rate of 36 percent is one of the world’s lowest, and at 19.6 percent it probably has the lowest female literacy rate in the world.18 Figure 13.6 compares Afghanistan’s literacy and enrollment rates with Pakistan and Thailand. With a tremendous youth bulge in the population and a transformation of attitudes toward education, the demand for education is growing rapidly, while expansion is constrained by the lack of schools, teachers, texts, and equipment. International assistance has concentrated on elementary education, and secondary and higher education are still limited, especially outside of major cities.19 Donors are also more likely to fund school buildings than teacher training, potentially leaving future governments with infrastructure they cannot use or maintain.20 Overcrowding and poor facilities at Kabul University led to demonstrations in November 2002. Inept police repression turned these demonstrations into riots in which six students were killed.

Figure 13.6 Human Capital Goods: Education and Life Expectancy (Indexed Comparison, Afghanistan = 100).

The government has responded to the country’s exceedingly poor state of health with a plan for a Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS), developed by the Ministry of Health with the World Health Organization. In view of its lack of capacity, the government is offering contracts to NGOs and international organizations to deliver these services in various locales.21 It will take time, however, to improve Afghanistan’s disastrous mortality and morbidity rates, which more resemble the most deprived, war-torn countries of sub-Saharan Africa than any country in Asia. As the comparison in Figure 13.7 illustrates, Afghanistan has some of the lowest health indicators ever seen, especially for women. UNICEF and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found in 2002 that the maternal mortality rate in Afghanistan was the highest in the world, estimated at 1,600 deaths per 100,000 live births, with pregnancy and childbirth complications accounting for nearly half the female deaths between ages fifteen and forty-nine.22 Afghanistan also ranks among the lowest in the world for infant and child health, with an infant mortality rate of 165 per 1,000 live births, an under-five child mortality rate of 257 per 1,000 (the fourth highest in the world), and 48 percent of children underweight for age.23

Efforts to lower infant, child, and maternal mortality have started.24 In 2002 UNICEF and the government reached 80 percent measles immunization, but UNICEF estimates that thirty-five thousand Afghan children still die of measles every year.25 Afghanistan recently recorded its first deaths from AIDS. Drug use and road construction will inevitably spread HIV unless preventive measures are undertaken.26

Figure 13.7 Human Capital Bads: Indicators of Mortality and Health. (Indexed, Afghanistan = 100).

Mental health has been neglected. Some surveys indicate that Afghans are among the world’s most traumatized populations, and that posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, sleep disturbance, substance abuse, domestic violence, and other syndromes are widespread.27 The current government includes a psychiatrist, Dr. Mohammad Azam Dadfar (minister of refugees), who has studied and tried to treat these disorders, but thus far Afghans have virtually no access to mental health services.

Transport

The government envisions transforming Afghanistan from a landlocked country to a land-bridge country, but investments have not kept pace with this vision. In fall 2002 President Karzai convinced President Bush that the United States should sponsor reconstruction of the Kabul-Kandahar highway. With great trouble, and with some Japanese assistance, a single layer of asphalt was laid down in a year. Reports claim that the road is already deteriorating after a difficult winter. Some other road improvement projects have begun, but Afghanistan still had only 0.15 km of paved road per 1,000 people and 16 percent of roads paved in early 2004.28 Pakistan, in comparison, has 0.72 km of paved roads per 1,000 people (see comparison in figure 13.8). Road building has been delayed by donor procedures and security concerns.

Figure 13.8 Infrastructure: Indexed Comparison of Afghanistan (100), Pakistan, and Thailand.

Municipal buses supplied by India and Japan have improved public transportation in Kabul, Herat, and Mazar-i Sharif. Kabul airport, controlled by ISAF, has improved in every respect since 2002, though it was so bad to begin with that it still does not meet the most basic international standards. The national air carrier, Ariana, and a few other carriers (UN, Azerbaijan Airlines, and private charters) have increased service to major cities and selected international destinations, but safety and quality are poor, as indicated by the February 4, 2004, crash of a KAM Air flight from Herat to Kabul. Corruption is high, and drug smuggling is reported as part of some operations. Ariana, a state monopoly, has blocked the expansion of service by others (e.g., Qatar Airways). High officials of the government claim that air transport is controlled by powerful “mafias.”

A transport issue of great symbolic and political importance has been the repeated scandals surrounding the travel of Afghan pilgrims to Mecca. The minister of aviation was murdered at the airport during the Hajj in 2002 and no one has been arrested, although (or because) evidence indicated that a high official of the Ministry of the Interior from the Shura-yi Nazar faction was responsible. In 2005, thirty thousand Afghan hajjis registered to travel, but only around ten thousand were transported until the last days, while the rest suffered in unheated waiting facilities during the winter. The new minister of aviation, Enayatullah Qasimi, succeeded in transporting all by exceptionally operating the airport around the clock for several days with lighting borrowed from ISAF. The country has no railroads.

Electricity and Energy

The availability of electricity was curtailed by both the war and the lengthy drought, and it has hardly improved. Foreigners, the powerful, and the wealthy rely on private generators, lessening pressure to improve public electrical supply. At the beginning of 2004, only 6 percent of Afghans had access to power, one of the lowest rates in the world (see Figure 13.8). A third of 234,000 energy consumers connected to the public grid were in Kabul.29 Yet Kabul receives electricity only intermittently even in the better-off neighborhoods. Some cities (Herat, Mazar-i Sharif) purchase electricity from neighboring countries, but there is a shortage of transmission lines, and supply is sometimes cut for failure to pay arrears. The government is considering several schemes to purchase more power from neighboring countries. There is no significant provincial or rural electrification. Among all National Development Program sectors, donors have disbursed the smallest proportion (11 percent) of their commitments to the energy sector.30

Fuel is available in part due to smuggling from Iran, which is subject to no quality control. North Afghanistan has natural gas, but the wells, capped in 1989, have not been rehabilitated. Other reported oil and gas deposits have not yet been explored. No efforts have been made thus far to exploit Afghanistan’s geothermal reserves.31

Water

Water scarcity is worsening, as a result of drought, population growth, and opium poppy cultivation. Organization of government for water management is poor, as it involves at least ministries for energy and water, mines and industry, public works, urban development and housing, rural development, and agriculture. Under the first phase of the cabinet reform, several ministries were merged to form the Ministry of Energy and Water. Afghans have less access to improved (let alone clean) water than any of their neighbors (Figure 13.8).

Public Employment

There has been little improvement in excessive but underpaid public employment. Generally public sector employment is in accord with the allotted amounts (tashkils), but the salaries are so low and the training of employees so poor (as are the systems they work with) that the public sector is nonetheless full of unneeded workers. The president has been understandably reluctant to authorize dismissals in the absence of alternative employment. Public sector overemployment is less of an issue than quality of service and corruption.32 Though hard to quantify, public sentiment feels that the influx of foreign aid, foreign contracting, and narcotics money has significantly worsened corruption.33 Afghans see foreign involvement more as the source of corruption than as its solution.

Agricultural Extension and Investment Support

With international aid, the Ministry of Commerce has opened the Afghanistan Investment Support Agency, which provides one-window service for granting investment licenses. It is now possible to register a company in one day, but Afghan businessmen still complain that the government hinders their legitimate activities.34 Banking and payment services have slightly improved with the currency reform and the opening of some banks, but land titles and legal services essential for legitimate business remain rudimentary to nonexistent.

Agricultural extension is being increased largely as part of the counternarcotics alternative livelihoods program, which means it is concentrated in a few poppy-producing provinces. The best functioning agricultural extension program in Afghanistan is still the one operated by opium traffickers.

Afghans characterize the situation of the past few decades and even today in most localities as “tufangsalari,” or rule by the gun, indicating the lack of rule of law or respect for human rights.35 In contrast to other Afghan governments since 1978, the current government does not carry out mass killings, mass arrests, or systematic torture of political opponents. Most abuse results from the weakness of national government compared to armed commanders, who often took power in localities in 2001–02 and have seen their positions legitimized by official appointments, including to the police. One detainee held for investigation during the recent UN hostage crisis died in custody, apparently as a result of torture, despite police reform. There are occasional charges of blasphemy levied against liberal or secular writers or newspapers, which have caused a few people to flee the country. Rights are also violated by the coalition, including homicides of detainees, arbitrary detention, and torture and mistreatment of detainees. There is no legal recourse for these violations, at least within Afghanistan.36 Taliban and elements linked to al-Qaeda conduct regular attacks on the government (especially police) and terrorist acts.

Protection of property rights, essential for economic development, seems to have deteriorated rather than improved. Afghans sometimes remark that protection of property rights has become worse since the overthrow of the Taliban, whose courts were more impartial and effective, and whose commanders were less corrupt, though at times very brutal. A Sikh businessman who said his property had been seized illegally under several governments made such a claim to one of the authors. Thirty-one percent of complaints received by the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) in the first half of 2004 were related to land grabbing by government officials.37

Land grabbing set off a major political scandal in 2003, involving an attempt by Defense Minister Muhammad Qasim Fahim to distribute land belonging to the ministry on which people had been living for decades to members of the cabinet and presidential administration. This incident was the subject of reports by both the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing and a special commission of inquiry.38 The latter report charged that a large majority of cabinet members were to have received land. Gul Agha Shirzai, governor of Kandahar, has openly allocated public land to his family members and followers. According to an email from a government official whose identity must be withheld to protect him:

Ismail Khan in Herat destroyed some houses and grabbed part of the people’s land to expand the land for the shrine of his son. In Takhar militiamen loyal to Daud grabbed land belonging to a weaker sub-tribe, which led to a relatively tense situation unresolved till now in Farkhar district. In Badakhshan, Commander Nazir Mohammed has started his own township and is creating a Yaftali settlement to consolidate his power in Faizabad. Iranians are secretly helping Shia to buy more land in Farah, Herat, and Mazar-i-Sharif as well as west of Kabul. In the Shamali plains [north of Kabul, Commanders] Almas and Amanullah Guzar are distributing government-owned land to their relatives and followers. Governors of Paktia, Nangarhar, Helmand, Uruzgan, and Khost have also been in one way or another involved in land grab.

The formation of a national leadership or political elite that agrees on the rules of legal, peaceful political competition is essential to stability. After years of violent intra-elite conflict and disruption of the social fabric, during which a number of elites were killed, arrested, persecuted, expelled, and dispersed to various parts of the world, Afghanistan’s leaders and skilled people are once again returning to Kabul and interacting with each other in a national framework. This process requires time to build both institutions and the trust to make them work. The reluctance of the losing candidates to accept the outcome of the presidential election shows how the lack of trust undermines adherence to rules.

The Bonn Agreement established an uneasy coalition government including commanders and officials of the United Front (Northern Alliance) and other Coalition-supported militias, former officials of the royal government, and some Western-trained Afghans without political affiliation. The new cabinet is largely composed of educated individuals without personal followings or armed groups. Except for Ismail Khan and Abdul Karim Brahui, they are not former commanders or warlords. A number of other NA officials have remained at their posts or even been promoted. One test of elite integration will be whether these leaders can perform well under the new conditions and be integrated into the new elite. Besides Ismail Khan, these include Foreign Minister Dr. Abdullah Abdullah, Army Chief of Staff Bismillah Khan, NDS Chief Amrullah Saleh, and Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs for Counternarcotics General Muhammad Daud. The next stage of elite integration will be development of a consensus over the election and conduct of the National Assembly and broadening the national leadership to include parliamentarians.

The security apparatus has made the first steps away from factional control and toward professionalism based on legal authority, but the newly trained portions of the security forces are still pilot programs confronted with the power of militia groups and drug traffickers. All security forces are now commanded by members of the “reformist” camp: Minister of Defense Abdul Rahim Wardak, Minister of Interior Ali Ahmad Jalali, and NDS head Amrullah Saleh. The UN secretary-general reports that reform of the Ministry of Defense is “now in its fourth and last phase.”39 NDS reform, though a late starter, has also progressed. The Ministry of the Interior, which has the larger and more complex job of managing both the police and the territorial administration, is still largely captured by commanders in some departments and at the middle and lower levels.

The trend of demobilization of militias and establishment of new security forces is positive, if mixed and slow. A contrary trend is the formation of unofficial armed groups by drug traffickers (also often commanders) and others. In early 2005 the Afghanistan’s New Beginnings Program (ANBP) of the UN began to survey such “illegal armed groups” (lAGs) with a view to demobilizing and disarming them before the Wolesi Jirga and provincial council elections.

Growth of the non-opium economy has slowed, just as the counternarcotics program has been launched. A counternarcotics policy with an inadequate program of alternative livelihoods and macroeconomic support and a premature emphasis on eradication is the most likely immediate source of economic retrogression and of consequent political and social conflict.

Figure 13.9 Growth of Opium-Related and Non-Opium-Related GDP, 2001–2004.

In 2002–03 and 2003–04 the legal Afghan economy was estimated to have grown by 29 and 16 percent per year respectively. In January 2005 the IMF downgraded its growth projection for 2004–05 to only 8 percent (see Figure 13.9), though a month later it projected slightly stronger performance (10 percent growth) for 2005–06.40 The growth in the first two years resulted in part from a rebound in agricultural production due to good rains after three years of severe drought and an influx of foreign aid, including the pump-priming effect of the hundreds of millions of dollars in cash supplied to commanders by the United States.41 Afghanistan estimated that a growth rate of 9 percent per year in the non-opium economy was the minimum needed for recovery. Thanks to government monetary and fiscal policy and an influx of foreign exchange, hyperinflation has abated.

Figure 13.10 Distribution of Opium-Related Income, 2001–2004 (UNODC Estimates).

The narcotics economy has been the most dynamic sector, though the gains appear to have gone mainly to traffickers and commanders and only secondarily to farmers, many of whom are heavily indebted (Figure 13.10).42 UNODC administrator Antonio Maria Costa has observed, “Just like people can be addicted to drugs, countries can be addicted to a drug economy. That’s what I am seeing in Afghanistan.”43 Afghanistan is now more dependent on narcotics income than any country in the world (Figure 13.11).

The economic opportunities of identity groups do not differ systematically at the national level. Leaders of all groups complain of discrimination in the pattern of public expenditure and distribution of aid. The lack of transparency in aid distribution, which depends largely on donors’ priorities and responses to perceived security threats, contributes to suspicions. Objectively, deprivation is shared, but the sense of injustice and need is so intense that even small perceived differences could incite strong resentments. Within families, women bear the brunt of the worst deprivation, including the sale of daughters for survival.

Otherwise, the major dividing line regarding economic opportunities is between the cities and the countryside and, within the cities, between those who can work in English and those who cannot. Most expenditure and aid goes to Kabul, though the expenditure in Kabul largely consists of salaries paid to the central government rather than public services to the city. This results not from discrimination but from lack of capacity to deliver services. The standard of living of many people in Kabul and other cities has actually deteriorated since the defeat of the Taliban. The opportunities for those with access to the aid economy, together with the spread of Western liberal social practices among both expatriates and the Afghans who work for them, has given rise to a nativist reaction. Imams preach on Fridays against foreigners, alcohol consumption, and cable television, which have provoked several fatwas from the chief justice. These are symbols of resentment and desperation over skyrocketing costs of housing and fuel, disruption of transport mainly by the huge U.S. presence, and neglect of urban services despite a visible influx of money.44

Figure 13.11 Narcotics-Related Income as Percentage of Legal GDP (Based on Estimates from UNODC and INCB, Various Dates, 2001–2004).

The poorest people in the country are probably tribal Pashtuns along the Afghan-Pakistan border, Pashtun nomads devastated by the drought, and the Hazaras in the Central Highlands. Emigration and remittances from family members working in the Persian Gulf Arab states or Iran have mitigated poverty among these groups since the 1970s. Moves to expel Afghans from Iran and other Persian Gulf countries would have an impact on them.

The legal status of women has greatly improved since the defeat of the Taliban. The new constitution guarantees legal equality and a presence in legislative bodies beyond what they enjoy in most developed countries. Women participated in both loya jirgas, where they were the most outspoken and controversial speakers. The school enrollment of girls is at an all-time high, though girls’ schools have been attacked in Pashtun tribal areas. These attacks do not appear to reflect community sentiment, which increasingly favors universal education.

Nonetheless, the deficits in education, health, social status, and economic opportunity of Afghan women are so deeply embedded in family and social structure that it will take generations to change them. Families still sell daughters to settle debts, forced marriage is common, and women are denied even the half share of inheritance to which Islam entitles them. Domestic violence against women is endemic, partly as a cultural phenomenon and partly as a result of the society’s unacknowledged trauma after a quarter-century of pervasive violence.

Demographic and environmental pressures are associated with demands for services that outstrip state capacity. In particular, a “youth bulge” in the population is statistically associated with outbreak of violent conflict, as uneducated, unemployed, and frustrated young men can be recruited to armed groups or organized crime. Afghanistan has such a youth bulge, with 45 percent of the population under the age of fifteen, more than any of its neighbors (Figure 13.12).45 A few simple improvements in health care that lower infant and child mortality (immunization, treatment for diarrhea) may soon make the population even younger, before demographic transition sets in. The expansion of education and employment is not able to keep up with the growth of the youthful population.

Figure 13.12 Percentage of Population Under Fifteen Years of Age.

Population pressure is particularly visible in the degradation of cities and the shortage of water. Several cities, most of all Kabul, are overrun with returning migrants, who have undergone forced urbanization as a result of displacement. Kabul, which was estimated to have a population of eight hundred thousand before the war, now contains more than three million people, on the same land and with less water. The consequences include traffic congestion and transport delays, crowded housing at skyrocketing prices, air pollution, and lack of sanitation. There are many illegal settlements on land without services. Shantytowns could become incubators for protest movements.

Availability of water has always been the main constraint on human settlement and agriculture in Afghanistan. During 1999–2001, Afghanistan suffered from one of the worst droughts in decades, lowering the water table as much as 15 feet (5 meters) in many areas.46 Several areas to which refugees and IDPs are returning (e.g., the Shamali plain north of Kabul) have had insufficient water to support them. Water shortage is also a constraint on food production needed to feed the growing population and an incentive for cultivating opium poppy, a drought-tolerant cash crop. Only tube wells can now reach the water table in some areas, and only poppy cultivation can produce the income to finance the operation of diesel-powered tube wells. These wells are mining the underground aquifers that constitute the country’s water reserves.47 One study reported the water table dropping by one meter per year in tube well areas.48

Other parts of Afghanistan’s environment have also become severely degraded. Both the hardwood forests of the east and the pistachio groves of the north have been rapidly depleted by peasants seeking firewood and timber merchants seeking construction materials. Soil quality has been eroded through lack of care and leeching by repeated poppy harvests. Air pollution in Kabul city is now among the worst in the world.49

Since 1978 more than a third of Afghans became refugees, and many were displaced within the country. Persecution killed and drove into exile many of the most skilled and educated Afghans. According to UNHCR, since the inauguration of the Interim Authority 3.5 million refugees have returned to Afghanistan, including all regions and ethnic groups.50 Refugees from Pakistan are pulled back to Afghanistan, while some refugees feel they have been pushed out of Iran. A smaller number of refugees and émigrés have returned from developed countries, sometimes to high positions. President Karzai asked eight members of the current cabinet to renounce citizenship in the United States, Germany, Switzerland, and Sweden. A few individuals have fled the country, sometimes temporarily, because of politically motivated threats, but such cases are rare.

A less visible brain drain, however, is depriving the country of much-needed capacity. Most Afghans with modern skills, especially those who can work in English, are now employed by international organizations in the dual public sector. Many working for the government are paid high salaries by donors, outside of the official framework. Efforts to build the capacity of Afghans in government stumble, as those trained leave to work for international organizations at far higher salaries, even if the new job is less skilled. In addition, as young Afghans receive more scholarships to study abroad, more decide to stay there. Whenever the international presence in Afghanistan diminishes, many Afghans now working for international organizations in Afghanistan will seek to emigrate, if current conditions persist.

During the consolidation of the power of Northern Alliance commanders in North Afghanistan in 2001–02, incidents of ethnic cleansing of Pashtun communities in northern Afghanistan displaced tens of thousands of people, now mostly sheltered in IDP camps around Kandahar.51 This violence, including some killings and rapes, was the latest round in disputes over control of land dating back to the settlement of Pashtuns in that area by the Afghan monarchy in the late nineteenth century. Some of the earlier rounds in which Pashtuns dispossessed non-Pashtuns were equally violent.

The government and UN established a security commission to help the IDPs return. IDPs in the Kandahar area also include nomads whose herds and pastures have been destroyed by drought. Both they and the victims of ethnic cleansing have now requested to be resettled on the barren land where they have been temporarily housed, for lack of any alternative.52

Security and survival are still so precarious in many areas that small disturbances can lead to forced migration. The residents of one border district with Pakistan belonging to the Mohmand tribe have reportedly decided to return to Pakistan [in 2005] because they will not be able to survive if the government prevents them from growing opium. Reduction or eradication of opium poppy production without sufficient alternative livelihoods may provoke more emigration.

The return of refugees and IDPs has generated numerous land and water disputes, as land titles and water rights, not always recorded in rural areas, have become clouded over decades in which successive occupants fled, sold, or leased land.53 According to a government official: “Land-related disputes have led to tribal clashes in Khost, Jalalabad, Takhar, Badakhshan, Kabul, Ghazni, Herat and Kapisa. … In Ghazni, Kuchis [Pashtun nomads] and Hazaras fought last year over pastures. In Nangarhar, two big tribes are at each other’s throat over the land grab issue.”

Many returnees to Kabul from the West found their former houses occupied by commanders. Returnees to rural land also find that their homes, land, and wells are occupied by others. Except for the expulsions of Pashtuns from the north, also related to land disputes, none of these has yet escalated to the political level, but the existing dispute resolution and legal institutions cannot resolve them satisfactorily.54

This land conflict in the north is one example of intergroup hostility, including mass killing and ethnic cleansing. Other instances of mass intergroup conflict or killing from the decades of conflict include:

• Killings and looting in Paghman (Kabul province) and in Kandahar by Jawzjani militias of the Najibullah regime in 1988–1996.

• The massacres of all communities that accompanied the battle for control of Kabul city among former mujahidin and former communist regime militias during 1992 and 1993.

• The scorched-earth policy of the Taliban and al-Qaeda in the Shamali plain north of Kabul, leading to the expulsion of many of the inhabitants, accompanied by extrajudicial executions and the destruction of land, crops, and property.

• The massacre of probably over a thousand Taliban prisoners by some Northern Alliance militias in Mazar-i Sharif in May–June 1997.

• The revenge massacre of probably several thousand Hazara and Uzbek civilians by Taliban in and near Mazar-i Sharif and at the Kunduz airport in August 2001.

• The executions of dozens or hundreds of Hazara civilians by Taliban in Hazarajat in summer–fall 1998, which was accompanied by a struggle over control of valuable pasture between Pashtun nomads and local Hazaras.

This is only a short list of better-known incidents. Especially because these events occurred during a civil conflict that included many instances of political or opportunistic killing and persecution with no ethnic overtones, Afghans disagree over whether it is legitimate to interpret these incidents as cases of ethnic conflict. In the absence of any political or judicial process of fact finding, accountability, or restitution, however, resentments that ethnopolitical entrepreneurs can exploit may grow.

Compared to the global neglect and regional interference of the 1990s, Afghanistan has benefited from the international attention it has received in the past few years. The country’s role as a front-line state in the U.S. Global War on Terror (GWOT) motivates continuing U.S. engagement but also risks embroiling the country in a conflict between the United States and Iran. Such conflict could threaten the formation of a regional consensus on the stabilization and sovereignty of Afghanistan, which is essential to peace and development there.

Afghanistan borders three regions: Central Asia, South Asia, and Iran and the Persian Gulf. All of these regions have exported and imported instability to and from Afghanistan. All neighboring governments officially support the current Afghan government and do not oppose the coalition presence there, though Iran protested the increased U.S. presence in western Afghanistan at the end of 2004, which was connected to the removal of Ismail Khan. All neighbors seek transit and trade agreements and compete for shares of trade with Afghanistan. Hence all have both growing stakes in Afghan stability and residual doubts about how long it will endure.

The India-Pakistan conflict has led Pakistan to try to impose a pro Pakistani government on Afghanistan to create “strategic depth.” Competition with Pakistan has led India both to support anti-Pakistan forces in Afghanistan and to seek to use Afghan territory for intelligence operations aimed at its neighbor’s rear. U.S. pressure after September 11 forced Islamabad to reverse its open support for the Taliban and toleration of al-Qaeda activities. Pakistan has collaborated in the search for al-Qaeda, but until recently the Taliban acted against Afghanistan from Pakistani territory with impunity. Some claim that the Pakistani intelligence agency, the Directorate of Inter-Services Intelligence (IS1), supported a low level of Taliban activity to exert pressure over the presence of Indian consulates in Jalalabad and Kandahar and to maintain a pro-Pakistani force in readiness for the day the United States leaves Afghanistan.

On the other hand, the burgeoning trade between Afghanistan and Pakistan, consisting largely of Pakistani exports to Afghanistan, has shown Pakistani elites that a stable Afghanistan can benefit Pakistan even if its government is not subservient to Islamabad. Current political trends have also alleviated some Pakistani concerns. The relative marginalization of the Northern Alliance, which Pakistan perceives as pro-Indian, is a source of satisfaction to Pakistan. Pakistan’s open advocacy of a Pashtun-ruled Afghanistan aggravates ethnic competition.

Russia and Central Asian governments have not been pleased with the change of fortune of the Northern Alliance, and they too aggravate ethnic conflict. The Russian minister of defense, Sergei Ivanov, recently provoked a harsh incident when he stated at a press conference with his counterpart in New Delhi that “attempts to Pashtunize Afghanistan” could lead to “a new war.”55

Iran collaborated with the United States in overthrowing the Taliban and establishing the Interim Authority. Only a few months later, President Bush labeled Iran a member of the “Axis of Evil.” Given the Bush Administration’s inflexible hard line on Iran, Iran has treated the U.S. presence in Western Afghanistan as a security threat. The Pentagon has not denied the report by Seymour M. Hersh in the New Yorker that special intelligence units of the DoD have used western Afghanistan as a base for covert operations in Iran, though officials of the coalition in Afghanistan have also tried to reassure Tehran.56 The U.S. decision to offer conditional support to the European negotiations with Iran may calm tensions temporarily, but the potential for disruption remains.

At the same time, Iran, in collaboration with India, has invested heavily in transportation infrastructure linking Afghanistan to Persian Gulf ports and has signed very favorable trade and transit agreements with Afghanistan. A stable Afghanistan with political space for Shia and some recognition of Shia jurisprudence is in Iran’s interest, but a U.S. military and intelligence presence on its border is not.

Landlocked Afghanistan desperately needs stable, secure relations with all its neighbors for transit to international markets. The same routes that Afghanistan needs for its international trade could also link the three bordering regions to each other and to the global market. Both hydroelectric and hydrocarbon energy sources could be transported from Central Asia to South Asia via Afghanistan. The best-known example of such transit projects is the proposed Trans-Afghan Pipeline (TAP), carrying natural gas from Turkmenistan to Pakistan. The three countries have signed protocols, and the ADB recently completed a feasibility study.57 Afghanistan has signed a protocol with Uzbekistan to provide transit to the Pakistani ports of Gwadar and Karachi, but this, like other transit projects, is held up by the slow pace of road construction and the lack of railroads. Regional markets in electricity, water, and labor can also be expanded.

Criminal and corrupt official elements in the surrounding regions are involved in the trade in opiates originating in Afghanistan, as well as other forms of trafficking (timber, persons). Figure 13.13 shows the main trafficking routes for opium according to UNODC. This map shows the path of opiates from Afghanistan to the retail markets. The direction of the arrows could be reversed, showing the path of demand, money, and precursor chemicals from markets and organized crime groups into Afghanistan. These organized crime groups have links to all security and intelligence services in the region and can also supply weapons and other contraband.

Coalition presence currently deters open regional competition, but the international community has not invested sufficiently in regional cooperation. The growing drug trade carries the potential for regional destabilization. Growing regional legitimate trade has the opposite impact, but the fear of drugs and other threats from Afghanistan makes neighboring countries reluctant to allow free passage of people or cargo.

Figure 13.13 Main Trafficking Routes for Opiates from Afghanistan. Source: UNODC.

At the start of the Bonn process all major Afghan state institutions either did not exist (parliament) or exercised limited functions under the control of armed groups. Many if not most trained personnel had been killed or fled the country. Soviet training produced some technical capacity in, for instance, health and engineering, but Soviet management models have added another level of resistance to reforms.

Efforts are under way to create new institutions. In some areas (central bank, Afghan National Army), the efforts have produced visible results. In other areas (judicial reform, civil service reform), almost no improvement is evident. Even in the most successful areas, the new institutions do not appear to be sustainable under current projections. In an effort to compensate for Afghanistan’s enormous gaps, donors have launched new institutions that quick calculations such as those presented at the start of this paper show could be financed by Afghanistan only if its GDP expanded by a factor of at least five. Although international commitments will certainly continue, an army that is completely funded by foreign powers will sooner or later (probably sooner) cease to behave or be perceived as a “national” army. Paying for all the operations of a security force one does not control will also pose dilemmas for funders, who may not want to be responsible for everything an Afghan army will do.

Most institutions and processes of transformation are perceived rightly or wrongly as politicized: Northern Alliance commanders and politicians have seen DDR as aimed against non-Pashtun militias, who were much better armed than Pashtuns. Some Afghans continue to complain, without clear evidence, that the ANA is predominantly Tajik or Panjshiri. Northern Alliance leaders suspect the minister of the interior of imposing a Pashtun agenda, while others accuse him of having done too little to break the hold of Panjshiris over his ministry. “Mujahidin” have accused the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission of serving the political agenda of its director, who has a past involvement with “Maoist” groups. Liberal or pro-democratic forces believe that the court system is controlled by followers of hard-line Islamist Abdul Rabb Rasul Sayyaf. Except for the president himself, there are no institutions that all sectors of the political elite consider reasonably impartial. That fact is a measure of both Hamid Karzai’s achievement and that achievement’s fragility.

Hamid Karzai became chairman of the Interim Administration without leading any powerful group, which enhanced his legitimacy by placing him above factionalism but deprived him of direct levers of power. The government consisted of a coalition of commanders with individuals either affiliated to the former king or with international technical skill or backing. Most ministers had no expertise in their ministries or administrative experience. The government executive has improved, but it is still lacking in political clout, policy expertise, and management skills.

The president’s style of leadership has been consensual and therefore sometimes appeared indecisive. Since being popularly elected, he has shown greater strength by, for instance, removing Abdul Rashid Dostum from the north and stopping U.S. plans for aerial spraying of opium poppy fields. He has projected a vision that commands considerable consensus both within the country and internationally. He has not shown comparable skills in ensuring implementation of the policies he articulates.

Many Afghans have seen President Karzai as dependent on the United States, and specifically on U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad. Though the president resisted U.S. pressure for aerial poppy eradication, Ambassador Khalilzad seems to have discreetly supported him against other actors in the U.S. government. The fact that the president is guarded by a U.S. private security company and sometimes relies on the United States and other foreign militaries for his transport damages his legitimacy, though many Afghans accept the need for such arrangements.

The cabinet has progressed as a decision-making body. It has passed four budgets, a process with which most cabinet members were not familiar. Despite being composed mostly of newcomers to government, it has far more responsibilities than other national cabinets, as it is both the executive and legislative body until the formation of the National Assembly. This dual responsibility has placed a heavy burden on the cabinet, leaving a backlog of unenacted legislation and insufficient attention to governmental management.

Professional support for the executive remains weak. The presidency and cabinet are only starting to constitute expert bodies of advisors on economic or strategic analysis or on policy making. The National Security Council has developed limited expertise in its own field. The presidency inherited a large bureaucracy (Idara-yi Umur, the Department of Administration) of about fifteen hundred employees, which has sometimes proved more of an obstacle than help. The lack of discipline in the president’s office has resulted in meetings with too many attendees and lack of note taking and follow-up, though discipline has improved since the president’s direct election.

The problem of succession remains. Under the constitution, should Hamid Karzai die or be incapacitated, the presidency would pass for three months to his first vice president, Ahmad Zia Massoud, who does not command a strong following in either his own group or the country at large. The country would be constitutionally obliged to hold new elections within three months; given the difficulty and expense of the last election, it seems unlikely that it could do so.

The professional army collapsed in 1992, leaving a vacuum of state power that was filled by various armed groups. After the fall of the Taliban, the military consisted of recently uniformed armed factions of common ethnic or tribal origin under the personal control of commanders, originating as anti-Soviet mujahidin or tribal militia of the Soviet-installed regime. The police served various factions, were corrupt, and routinely beat those they arrested. The courts and attorneys-general had no legal texts; hence they tended to apply a rudimentary conservative interpretation of the Islamic sharia.

Annex 1 of the Bonn Agreement called upon the Security Council to deploy an international security force to Kabul and eventually other urban areas, for the militias to withdraw from Kabul and eventually those other areas to which the force would deploy, and for the international community to help Afghans establish new security forces. Those new security services have made the first steps away from factional control and toward professionalism based on legal authority, and the power of warlords and commanders at the national and regional levels has diminished. Many if not most localities, however, are still under their sway, as the central government initially appointed commanders to official positions, often in the police, in the areas where they seized power. The government is now trying to transfer some of them away from their places of origin, and hence their power bases.

The Afghan National Army (ANA) could defeat any warlord militia, but the security strategy of the government, UN, and coalition is based almost entirely on negotiation and incentives, not confrontation. The structure, size, and mission of the new security forces have not been the subject of any Afghan political deliberation and have resulted more from the decisions of the major donors and troop contributors.

The security services consist of the army and air force under the Ministry of Defense; the police forces, including national, border, highway, and counternarcotics under the Ministry of the Interior; and the intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security (NDS). All consist of a combination of low- to midlevel personnel who have served all governments, commanders, and others from the militias that took power at the end of 2001, and new units trained by donor and troop-contributing countries.

The former militias now within the Ministry of Defense are referred to as the Afghan Militia Forces or AMF, while the new army trained by the United States with help from the UK and France, and deployed with embedded U.S. trainers, is the ANA. Within the Ministry of the Interior, the newly trained forces are called the Afghan National Police (ANP), while the border, highway, and counternarcotics police are new units. Demobilized militia fighters constitute fewer than 2 percent of the ANA, with the rest being fresh recruits, while the ANP consists largely of retrained militia and former MoI personnel. The NDS leadership was changed after the Constitutional Loya Jirga, and the new director is gradually introducing new personnel and structures.

In addition to this formal security sector, there is also an “informal” security sector, composed of numerous militias and private security agencies employing both Afghans and foreigners for a variety of tasks. The coalition has funded, armed, and deployed militias for fighting the insurgency. The United States and UN have hired private military and security contractors (Global Risk, Dyn-Corp) to provide security for President Karzai, elections, road construction, poppy eradication, and other tasks. International actors often respond to the inadequacy of Afghan security forces by creating ad hoc armed groups for specific purposes without any clear legal framework. The result has often been confusion on the ground. The authors of a study of security for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit depicted the security “architecture” of Afghanistan in early 2004 in the diagram reproduced in Figure 13.14.58

The establishment of a lawful military consists of (1) disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) of the militia forces; (2) reform of the ministry of defense; and (3) the training of the new army. These processes were linked. Many commanders refused to demobilize so long as the MoD was under factional control. MoD reform met with considerable resistance under Defense Minister Fahim. Rahim Wardak, a U.S.-trained professional soldier from the royal regime, who also served as a military official of the anti-Soviet mujahidin, enjoys the confidence of the UK and United States. Chief of Staff Bismillah Khan, former deputy of Ahmad Shah Massoud, is a respected former mujahid who, unlike Fahim, has inherited Massoud’s honorific “Amir sahib” (chief commander). He may help integrate new and old elements in the ministry.

According to some reports, however, the diversification of the ministry’s personnel is occurring through negotiation among diverse patronage networks, rather than through a unified merit-based system. One security official claimed:

The candidates who fill these positions will naturally have their first loyalty to their ethnic group not to the system, because it was not the system in the first place that gave them a position, but their ethnic group, and their loyalty is to a guy, not to the government. This will work fine as long as CFC-A [the coalition] is there but will disintegrate into factions and ethnic division immediately after cessation of US funding.

Figure 13.14 Security Architecture of Afghanistan, Early 2004. Source: Courtesy of Bhatia, Lanigan, and Wilkinson (2004).

This is precisely what happened to the Soviet-trained Afghan national army after the withdrawal of Soviet troops, which had kept a lid on factional fighting. Thirteen months after the Soviet withdrawal, Khalqi sections of the armed forces launched a failed coup against President Najibullah and the sectors of the security forces controlled by their factional rivals, the Parchamis.

ANBP reported that as of February 2005 the DDR process had cantoned 8,630 heavy weapons, with seven regions considered free of unsecured heavy weapons.59 Despite initial resistance, by March 2005 all known heavy weapons had been cantoned in the Panjshir Valley, the last untouched major weapons cache. UNAMA has announced the completion of DDR in northern Afghanistan. ANBP is expected to conclude the demobilization of the AMF by June 2005.60

DDR has thus far dealt only with the AMF, those militias previously integrated into the Ministry of Defense. A new program of disbanding of Illegal Armed Groups (IAGs) is expected to start in April 2005, in coordination with the counternarcotics program, since many IAGs are involved with trafficking. Unlike the AMF, the IAGs will receive no incentives, and more resistance may occur.

Disarmament has referred only to the cantonment of heavy weapons. No effort has been made to collect all automatic rifles and other weapons possessed by households. Hence many policies, such as counternarcotics, must take into account that much of the population is still armed for guerrilla warfare. Reintegration is less successful, as the economy is not expanding quickly enough. Anecdotal evidence from northern Afghanistan suggests that demobilized fighters who kept their weapons may be preying on the population. One security official described the creation of “insecurity in vast areas of Afghanistan from Khairkhana to Wakhan and to Murghab River in Badghis,” effectively in most of Afghanistan north of Kabul.

The ANA was reported to have twenty-one thousand men on duty as of February 2005 and is continuing to grow.61 It appears to have overcome to some extent the problems of ethnic imbalance and high turnover that plagued it at the start. Growth has been slow, due to a valid emphasis on quality of recruits and training.

The ANA was originally deployed full-time only to the Central Garrison in Kabul, with mobile units occasionally going to the provinces. In 2005 the ANA is scheduled to be permanently deployed to the four major regional military garrisons. The ANA has performed well in the limited tasks it has been assigned, mainly involving stabilization operations where warlords have been weakened. It has not been consistently deployed on the front lines in the war against the Taliban.

The plan for the ANA calls for a force of seventy thousand men, a number that appears to have been chosen by the United States through negotiation with Marshall Fahim. Currently the ANA is entirely funded by international donors, mainly the United States, and also relies on the direct participation of embedded U.S. trainers. The troops are currently paid several times more than civil servants. Some analysts believe that the use of full cash payment rather than the provision of in-kind services for soldiers and their families weakens the attachment of soldiers to the institution. Soldiers must often go on leave to deliver pay to their families, some of whom live in Pakistan, where housing is cheaper than in areas of Afghanistan where land prices are inflated by drug trafficking and the international presence. The Afghan national government is unlikely to be able to sustain a force of this size, salary level, and technical sophistication using its own resources.

Police in Afghanistan have always been concerned more with the security of the state than that of the public. They included only a national gendarmerie, whose paramilitary units expanded during the Soviet period. There was no local or community policing. Villages, where most of the population lived, provided their own security. By the start of 2002, Afghan police could have been the subject of Walter Mosley’s novel Always Outnumbered, Always Outgunned.

Reform started with the appointment of Ali Ahmad Jalali as minister in November 2002. Jalali, then head of the Persian Service of the Voice of America, had been a military officer and professor of military history at the Kabul Military Academy before 1978. In exile in the United States, he had published several well-regarded books and articles on the military history of Afghanistan.