The False Promise of Crop Eradication

In the past year (2007–08), opium production in Afghanistan reached a record level, estimated at 8,200 tons of raw opium. Traffickers also refined much of the opium into heroin before exporting it. The Taliban-led insurgency supported by al-Qaeda spread to new areas in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. The level of terrorism, especially suicide bombings, set a record in both countries, hitting high-profile targets such as Pakistan’s most popular politician, Benazir Bhutto, and the Serena Hotel in Kabul. After six years of assistance to the Afghan government by the UN, NATO, the world’s major military powers, the world’s largest aid donors, and international specialists on all subjects, the expansion of both the illicit industry and the insurgency constitutes a powerful indictment of international policy and capacity.

In response, the U.S. government and other major actors decided to make counternarcotics in Afghanistan a priority in 2007 and 2008 and link it to counterinsurgency. To ensure coherence and coordination of this complex policy area, the government of Afghanistan and the United Nations agreed that the February 6, 2008, meeting of the Joint Coordination and Monitoring Board, a multilateral body that oversees implementation of the Afghanistan Compact and that they cochair, should focus on counternarcotics.1 This meeting could reach agreement on effective measures to cope with the opiate industry and insurgency in Afghanistan, but it could also confirm international commitment to escalating eradication of the poppy crop in 2008, a policy that will invigorate both the opiate industry and the insurgency.

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) led off its Afghanistan Opium Survey 2007 with findings linking the opium economy to the insurgency. It first summarized trends in opium cultivation2:

First, the area under opium cultivation rose to 193,000 hectares from 165,000 in 2006. The total opium harvest will be 8,200 tons, up from 6,100 tons last year….

Second, in the centre and north of Afghanistan, where the government has increased its authority and presence, opium cultivation is diminishing. The number of opium-free provinces more than doubled from six to thirteen, while in the province of Balkh opium cultivation collapsed from 7,200 hectares last year to zero. However, the opposite trend was seen in southern Afghanistan. Some 80 percent of opium poppies were grown in a handful of provinces along the border with Pakistan, where instability is greatest. In the volatile province of Helmand, where the Taliban insurgency is concentrated, opium cultivation rose 48 percent to 102,770 hectares.3

UNODC then “highlight [ed] three new circumstances” that linked the increase in opium poppy cultivation to the insurgency:

First, opium cultivation in Afghanistan is no longer associated with poverty—quite the opposite. Helmand, Kandahar and three other opium-producing provinces in the south are the richest and most fertile, in the past the breadbasket of the nation and a main source of earnings. They have now opted for illicit opium on an unprecedented scale (5,744 tons), while the much poorer northern region is abandoning the poppy crops.

Second, opium cultivation in Afghanistan is now closely linked to insurgency. The Taliban today control vast swathes of land in Helmand, Kandahar and along the Pakistani border. By preventing national authorities and international agencies from working, insurgents have allowed greed and corruption to turn orchards, wheat and vegetable fields into poppy fields.

Third, the Taliban are again using opium to suit their interests. Between 1996 and 2000, in Taliban-controlled areas 15,000 tons of opium were produced and exported—the regime’s sole source of foreign exchange at that time. In July 2000, the Taliban leader, Mullah Omar, argued that opium was against Islam and banned its cultivation (but not its export). In recent months, the Taliban have reversed their position once again and started to extract from the drug economy resources for arms, logistics and militia pay.

These assertions are misleading and partly false. They have been cited in support of a plan to escalate poppy eradication, especially in the South, to deprive the Taliban of funding and starve the insurgency. The proponents of this plan have also justified it on the grounds that it will not harm the “poor,” who are in the north, but only the “rich and greedy” in the south. These arguments consist of a series of fallacies:

• First, the difference between the “rich” southern province of Helmand and the “poor” northern province of Balkh, according to UNODC’s own survey of household income, is the difference between an average daily income of $1 per person in Helmand and $0.70 per person in Balkh.4 Household studies of poppy cultivation in Afghanistan indicate that poor households are most dependent on poppy cultivation for their livelihoods. Poppy eradication in Helmand, especially in insecure areas not reached by development projects, may primarily harm the livelihoods of those earning less than $1 per day. The first UN Millennium Development Goal aims to reduce by half the number of people living on less than $1 per day. If these desperately poor people have easier access to armed resistance than alternative livelihoods, they may well choose the former.

• Second, poppy (or coca, or cannabis) cultivation migrates to the most insecure areas capable of producing it. Hence poppy cultivation migrated to Afghanistan and within Afghanistan to the areas most affected by the insurgency. Political and military conflict created the conditions for the drug industry, not vice versa, just as political and military conflict previously created conditions for cultivation of narcotics raw materials in Colombia and Burma. Field research on poppy cultivation has identified insecurity exploited by drug traffickers, not the greed and corruption of Afghan cultivators, as the primary driver of opium poppy cultivation.

• Third, the Taliban were not solely dependent on narcotics financing in 1996–2000; nor are they now. Research by the World Bank and others, including UNODC, indicated that the Taliban derived more income and foreign exchange in the 1990s from taxing the transit trade in licit goods smuggled through Afghanistan from Dubai to Pakistan than from the drug trade.5 Today, too, the Taliban have other sources of income.

The advocates of responding to the drug problem by escalating eradication compound these errors with a further fallacy: the claim that poppy eradication reduces the amount of drug money available to fund insurgency, terrorism, and corruption. In 2000–01, when the Taliban prohibited poppy cultivation with almost complete success in the areas they controlled, they suffered no financial problems. Drug traders are not florists. Trafficking continued from stockpiles of opiates, and the loss in quantity was compensated by a tenfold increase in price. Eradication raises the price of opium and causes its cultivation to migrate to more remote areas. It does not provide for a sustainable reduction in the drug economy; nor does sustainable reduction of the drug economy start with eradication.

Focusing on poppy cultivation when economic alternatives are not secure conflicts with the broadly accepted view in Afghanistan that poppy cultivation is undesirable, but that it is inevitable in situations of dire poverty and insecurity. Hence pursuing eradication under these circumstances provides evidence that the international operation and the government that it supports derive their legitimacy not from Afghan people but from external powers.

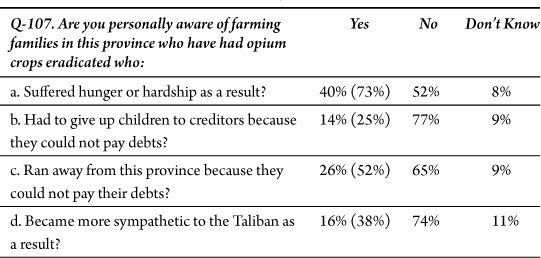

According to a 2007 poll conducted by Charney Research, 36 percent of the national sample in Afghanistan (in both poppy-growing and nonpoppy-growing provinces) believed that poppy cultivation was acceptable either unconditionally or if there was no other way to make a living. In poppy-producing provinces, a third of respondents believed that elimination or reduction of poppy was a bad thing. In Helmand, the main province targeted for eradication, this figure climbed to about one-half. More than 60 percent in all poppy growing provinces and 80 percent in Helmand agreed that the farmers whose opium crops are eradicated are usually poor or don’t pay bribes. Table 16.1 illustrates the perception of hardship imposed by poppy eradication in poppy-growing provinces (figures for Helmand in parentheses).6

Note that one out of seven respondents in poppy-growing provinces and one in four in Helmand said they knew of farming families who had sold their children (most likely girls) in payment of opium debts as a result of eradication. This might help explain why 38 percent of the Helmand respondents said they knew of someone who became more sympathetic to the Taliban as a result of eradication.

Table 16.1 Perceptions of Hardship as a Result of Poppy Eradication (Results from Helmand in Parentheses)

The Afghanistan Compact requires a different approach to counternarcotics. That agreement outlines a strategy to achieve two overriding goals: “to improve the lives of Afghan people and to contribute to national, regional, and global peace and security.” To accomplish these goals, the compact prescribes three pillars of activity: security; governance, human rights, and justice; and economic and social development.

The compact defines counternarcotics as a “cross-cutting” theme across these three pillars. It integrates counternarcotics with the other pillars both because achieving counternarcotics goals requires policies and programs under all pillars, and to emphasize that counternarcotics is not separate from or parallel to the overall goal of the compact and its three pillars. Achieving the compact’s counternarcotics goal, “a sustained and significant reduction in the production and trafficking of narcotics with a view to complete elimination,” is part of an overall strategy to build security, governance, and development to improve the lives of Afghans and provide security to Afghans, their neighbors, and the entire international community.

The threat to the compact’s objectives comes not from drugs per se but, as stated in the U.S. Counternarcotics Strategy for Afghanistan, from “drug money” that “weakens key institutions and strengthens the Taliban.”7 According to estimates by UNODC, the “drug money” to which the Strategy refers comes mainly from the 70–80 percent of the gross profits of narcotics earned by traffickers, processors, and protectors, including Taliban, Afghan government officials, and other illegal armed groups, not from the 20–30 percent that goes to poppy farmers and laborers.8

Counternarcotics policy in service of the Afghanistan Compact’s goals requires reducing the amount of illicit value created by the drug economy and should focus on the part of the drug economy that “weakens key institutions and strengthens the Taliban.” This distinction has implications for how to define and measure success in counternarcotics and how to achieve it. The most commonly used measure of both the problem and the progress of counternarcotics—the extent of cultivation of opium poppy—biases policy in the wrong direction. It focuses attention on the quantity of narcotics rather than the value and toward the smallest and least harmful part of the drug economy: the raw material that produces income for rural communities. A better indicator of success is the one included in the benchmarks for economic and social development of the Afghanistan Compact: “a decrease in the absolute and relative size of the drug economy.”

The Afghan narcotics industry, the annual gross profit of which is equal to approximately half of the country’s licit GDP, makes a significant proportion of the Afghan population dependent for their livelihood on drug traffickers and those who protect them, whether corrupt officials or insurgents.9 This includes not only the one in seven Afghans who are involved directly in poppy cultivation according to UNODC—a figure that excludes sharecroppers and laborers from outside the village where the question was asked—but also all those involved in trafficking as well as the commerce, construction, and other economic activities that narcotics revenue finances. The political goal of counternarcotics in Afghanistan is to break those links of dependence and instead integrate the Afghan population into the licit economy and polity, which are in turn integrated with the international community’s institutions and norms. This effort is the equivalent of the counterinsurgency goal of “winning hearts and minds” and the postconflict reconstruction goal of strengthening legitimate government and reconstruction.

Both globally and within Afghanistan, the location of narcotics cultivation is the result—not the cause—of insecurity. The essential condition for implementing counternarcotics policy is “a state that works.”10 Counternarcotics can succeed only if political efforts establish the basis for policing, law enforcement, and support for development. Unlike military action, policing and law enforcement require the consent of the population. State building includes military action to defeat armed opponents of the project, but in a weak state such as Afghanistan it succeeds only by limiting the scope of state activity and gaining sufficient legitimacy and capacity so that the population consents to the state’s authority over those areas in which it acts. Winning consent for counternarcotics requires providing greater licit economy opportunities, and providing security for people to benefit from those opportunities. Scarce resources for coercion should be reserved for targeting political opponents at the high end of the value chain, rather than farmers and flowers. Winning a counterinsurgency while engaging in counternarcotics also requires acknowledging that the transition from a predominantly narcotics-based economy to a licit one will take years. It is not possible to win the consent of communities to state authority while treating their livelihoods as criminal, even where alternatives are not yet reliable.

Proponents of escalating forced eradication argue that the government and its international supporters do not have years; if the drug economy continues to expand, the whole effort will fail. Escalating forced eradication, however, will only make the effort fail more quickly.11 Escalating forced eradication does not integrate counternarcotics with counterinsurgency; it makes counternarcotics a recruiter for the insurgency. What drives rural communities to align themselves with the Taliban is not illicit drugs but a program to deprive those communities of their livelihoods before alternatives are available. An internationally supported effort to help Afghan communities gradually to move out of dependence on the drug trade without being stigmatized as criminals during the transition will integrate counternarcotics with counterinsurgency and peace building. Many of the “substitute” crops being suggested by the USAID Alternative Livelihoods Program (ALP) and others, such as saffron, pomegranates, apricots, and roses, have maturation periods of several years during which they will not provide income.12

In areas where the government and its international supporters have access to the population (including both poppy-growing and nonpoppy-growing areas), a gradual policy should focus first on development of licit livelihoods; improving governance, including reduction of narcotics-related corruption; and interdiction, targeted especially against heroin production. The international community must contribute by ensuring markets for licit Afghan products, cooperating in interdiction with intelligence and force protection, preventing the import of precursors for heroin production into Afghanistan, and ensuring that its operations in Afghanistan do not enrich or empower traffickers. Many international organizations in Afghanistan employ private security companies linked to figures involved in drug trafficking or rent properties from such men. At least two organizations funded by USAID for the ALP rent their premises from men reputed to be major drug traffickers.

In areas where the insurgency prevents regular access by government, the first priority should be to gain access and establish state presence with consent of the local population. Introducing forced eradication whether by air or on the ground before the government is able to provide security or help communities develop alternative sources of livelihood undermines this effort.

The recovery of control over Musa Qala district of northern Helmand followed the pattern of putting access and security first, followed by interdiction and alternative livelihoods. The Afghan government and international forces carried out a joint political-military operation, gaining the support of a major Taliban commander (Mullah Abdul Salaam) and then defeating the remaining insurgents. Once in occupation of the district, government and international forces seized about $25 million worth of narcotics13 and destroyed more than sixty heroin laboratories.

Confiscating products from the upper end of the value chain depended on regaining control of the territory. Had the government and international community engaged in forced eradication in Musa Qala before launching the operation, Mullah Abdul Salaam might not have changed sides, the local people might not have supported the government or remained neutral, and the district might have remained under Taliban control. If eradication had destroyed locally produced raw opium, the Taliban-supported heroin laboratories could have purchased opium from other sources. Having first undertaken political and military measures to establish security in Musa Qala, however, Afghan and international forces were able to interdict high-value illicit products without harming rural communities. They now can help communities break their dependence on the drug trade. This is how to integrate counternarcotics and counterinsurgency.

For both political and economic reasons, crop eradication should be implemented, as stated in Afghanistan’s National Drug Control Policy, “where access to alternative livelihoods exists.” Where communities are confident in alternative livelihoods, they will consent to the eradication of illicit crops.

From an economic point of view, crop eradication does not meaningfully increase the opportunity cost of illicit cultivation unless the cultivators are able to engage in other cash-earning activities.14 Afghan farmers do not cultivate poppy out of greed for the highest possible return. They cultivate it because for many it is the only way to supplement their subsistence farming with a cash income for food and social security, which has become essential over the past few decades of war-induced inflation and destruction of the rural economy. The drug economy provides the only access to land, credit, water, and employment. There are many potential cash crops and sources of monetary income other than poppy cultivation, but additional investments and more security are required to make these economic opportunities available to most Afghan communities, especially those more distant from markets and in areas with less government presence.

From a political point of view, where these opportunities are available, eradication is hardly necessary, except to discipline some deviants, which communities can do themselves. Where these opportunities are not available, eradication promotes corruption and insurgency rather than alternative economic activities. Implementation of “forced eradication” in the absence of such conditions will neither reduce the size of the narcotics economy nor weaken the insurgency. Rather, it will strengthen insurgency while weakening and corrupting the Afghan government. Afghans will conclude that foreigners are in Afghanistan only to pursue their own interests, not to help Afghanistan.

The narcotics industry’s profit derives from illegality. Producing a banned substance imposes two kinds of costs: (1) costs of production and marketing (capital, labor, land, transport), and (2) costs of illegality, including bribes, formation of illegal military organizations, and direct violence and deprivation of liberty and income resulting from law enforcement. The risk premium increases up the value chain from farmgate to retail distributor. Afghanistan’s principal comparative advantage is not in poppy cultivation but in the production of illegality and insecurity.

The volume of production of illicit raw materials is mainly determined by demand from the richer consuming countries, but the location of production of raw materials responds mainly to shifts in security. Narcotics raw material production is often preceded by political destabilization, which the drug industry exploits. The migration of drug production to insecure areas in turn attracts investment of criminal capital to the destabilization of trafficking routes.

In Afghanistan, the state collapsed as a result of the 1978 communist coup d’état, the growth of the mujahidin movement, and the consolidation of international and transnational economic, military, and political support for both. Afghan political-military leaders allied with businessmen engaged in licit trade, arms dealing, smuggling, gem mining, timber trafficking, transit trade (smuggling to neighboring countries), antiquities smuggling, and drug trafficking. The businessmen depended on the strongmen for protection and patronage and in turn supported them financially. Such alliances often took the form of a division of labor among members of a family, with some brothers or cousins specializing in political-military activity and others in business.

At the same time, intensified counternarcotics efforts outside of Afghanistan raised the risk premium in several areas where poppy had been produced. The international drug industry seized the opportunity to move production from Turkey, Iran, and Pakistan to Afghanistan. It did so through links established in the late 1980s and early 1990s with strongmen in Afghanistan. They controlled access to (1) agricultural land where poppy could be grown, (2) markets and roads through which opium could be traded, (3) locations where heroin refineries could be established, and (4) with their international partners, the physical, administrative, and virtual borders of Afghanistan, the crossing of which was necessary for the export of opiates, the import of precursors for heroin manufacturing, and the transfer of money to pay for these transactions.

The initial links came through traffickers in Pakistan. After 1992, as the Eurasian “mafia” developed in the former Soviet Union, it entered the drug industry, establishing new routes to Western Europe. The civil war in Tajikistan, lasting from 1992 to 1997, facilitated the extension of the Eurasian drug trafficking mafia into Afghanistan. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) established bases in areas of Tajikistan between the Ferghana Valley and opium-producing areas of north Afghanistan. The IMU’s military efforts in the late 1990s appeared partly motivated by attempts to secure these trafficking routes.

The drug trade expanded further under the Taliban, because the Islamic Emirate was a peculiar type of state: internally it strictly enforced its own law and brought security to trade routes and rural areas, but the government was not recognized internationally and did not recognize international law, including the international counternarcotics regime. The Taliban issued several religious decrees (fatwas) stating that although narcotic consumption was strictly forbidden, production and trade of narcotics was merely inadvisable and could be undertaken in case of necessity. The latter provision essentially “legitimated” the opium economy within Afghanistan until the Taliban ban on cultivation in 2000–01. As the trade was taxed rather than banned, it remained a relatively competitive industry that produced only modest revenues and little corruption inside Afghanistan, compared to today.

As the Taliban took control of southern and eastern Afghanistan, increased security facilitated trade and hence the growth of poppy production in the two main areas with good natural endowments under their control, the irrigated areas in Helmand-Kandahar and Nangarhar. The other main production area, in Badakhshan, was mainly linked to the Eurasian route and was controlled by Northern Alliance commanders.

After 1998, as the Taliban consolidated control over most of northern and western Afghanistan, the trafficking markets became more integrated. Trafficking routes linking the north and south developed. Today, profits from drug trafficking persist in the “poppy-free” north, as raw materials are shipped over the Hindu Kush through various trade routes (via Chaghcharan in Ghor or the Shibar Pass linking Bamyan and Balkh).

In 2000, responding to pressure from both the international community and major traffickers, the Taliban used their authority to reduce the quantity of land cultivated in poppy by 95 percent. This was one of several instances when power holders with strong links to the drug trade sought recognition or support from the international community by using their influence and power to reduce poppy cultivation. Other instances include Helmand (1988 and 2002–03), Nangarhar (2004–05), and Balkh (2006–07).

At that time, as has also happened since, the accumulation of inventories (a form of risk management in an illicit business) created a tactical convergence of interest in reducing production of the raw material between drug traffickers and counternarcotics officials. The Taliban hoped both to win international recognition and aid, and to enjoy a fiscal bonus from taxes levied on trade inflated by the huge rise in price. Counternarcotics officials got to improve their “metrics of success.” The farmgate prices of raw opium increased tenfold. This increase was transmitted up the value chain to traffickers in Afghanistan and then largely absorbed in the profit margins of the supply chain outside Afghanistan. Prices have declined since the Taliban were ousted from power, but they have not returned to the competitive levels of the previous period when the drug economy was not subject to sanction inside Afghanistan.

Military action by the U.S.-led coalition after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States led to a collapse of opium prices as traffickers engaged in panic selling of their stocks, anticipating attempts at seizure by the international forces. It soon turned out they had nothing to fear. The coalition regarded counternarcotics as mission creep, a distraction from the core task of killing and capturing terrorists. Nonetheless, the gradual adoption of de jure counternarcotics policies after conclusion of the first round of major military operations increased the cost of illicit business.

The United States and Iran jointly drafted an article included in the Bonn Agreement that provided the framework for the transition to the current government, requiring the new authorities in Afghanistan to “cooperate with the international community in the fight against terrorism, drugs and organized crime.”15 The current government is committed to (in the words of the preamble to the Constitution of 2004/1382) “restoring Afghanistan to its rightful place in the international community.”16 Hence, the constitution provides: “The state shall prevent all types of terrorist activities, the production and consumption of intoxicants (musakkirat), and the production and smuggling of narcotics.”

The drug industry consequently has had to conceal some of its trafficking operations. This has required corrupting the administration, especially the police and the justice system. The rise in the cost of corruption has led to the consolidation of the industry, as only larger traders can afford the increased bribes and protection from political authorities.17 Counternarcotics efforts (as well as counterinsurgency efforts) have supported the consolidation of market share by strongmen allied to power holders, just as production restraint under the Taliban served the interests of traffickers.

During the early years of the Bonn process, drug trafficking had only a marginal relationship to the Taliban and al-Qaeda. The drug trade was associated with the power holders, not with those contesting them. Just as drug production and trafficking exploit insecurity created by political factors, the insurgency began for political reasons but then maintained and created insecurity advantageous for narcotics production and trafficking. As a result, the most visible part of the industry (poppy cultivation) has become concentrated in the most insecure and insurgent-ridden regions of the country.

Participants in the narcotics economy—which comprises about a third of the total Afghan economy and at least half of the cash economy—must govern it through illegal activities. Afghan police and administrators, political leaders, and the antigovernment insurgents all offer protection services to poppy growers and drug traffickers. Competition for this lucrative role motivates much of the violence in the country and funds official corruption, such as the sale and purchase of offices in poppy-growing areas and along trafficking routes.

Hence, even though the illegality of the narcotics economy corrupts and weakens the government, undermines stable economic development, and funds terrorism and insurgency, the rents from that illegality fund security to the drug economy.18 From the point of view of Afghan poppy cultivators, it is eradicators who provide insecurity, while leaders (whether in the government or the Taliban) who keep out or corrupt eradicators provide security.

Opium is a gum harvested from the mature flower of the opium poppy, Papaver somniferum, by scraping the bulb with a specially designed knife. Opium has medicinal uses, but it can also be ingested orally or smoked as an addictive narcotic.

Relatively simple chemical reactions transform the active ingredient in opium gum into stronger narcotics: morphine, codeine, or heroin. These reactions require precursor chemicals that act as reagents in the manufacture of organic compounds. The principal precursor for opium processing is acetic anhydride, which is also used in the manufacture of aspirin and photographic film.

The value chain includes transactions at ascending prices. Cultivators sell raw opium at the farmgate, often as repayment of a debt under a futures contract. In recent years, as more processing has taken place in Afghanistan and the risk premium of trafficking has increased, cultivators have received at most 20–30 percent of the gross profits. The rest goes to traffickers, processors, and protectors.

The primary traffickers sell raw opium to larger ones or processors at opium bazaars. Specialized workshops (the term “laboratory” may conjure a deceptive image of white coats and stainless steel) refine the opium into heroin using precursor chemicals and scientific expertise. Traders consign shipments of the opiates either to individual smugglers, whose families are held accountable for the value in case the smuggler fails to return with the money, or to illegal armed groups, whether political or purely criminal, which transport it across the border. Prices increase exponentially as one ascends the value chain, accounting in part for the increasing share of opiate profits going to traffickers.19

At each stage of the value chain, power holders take shares of the profit. In villages, farmers often contribute a share of their profit to the mosque (sometimes couched as the Islamic tax, ushr, which is paid on all agricultural produce), which is used to pay the mullah and for local public expenditures, such as teachers’ salaries, medical care, and irrigation. When eradicators come to the village, either the village may decide collectively which land is to be eradicated and compensate the cultivators, or the richer or better-connected villagers may make individual payments to have their land exempted.

The small traders who come to the village have to pay the police (or bandits) whom they pass on the road, who pass a share up to their superiors. The police chief of the district may have paid a large bribe to the Ministry of the Interior in Kabul to be appointed to a poppy-producing district; he may also have paid a member of parliament or another influential person to introduce him to the right official in Kabul. These officials may also have paid bribes (“political contributions”) to obtain a position where they can make so much money.20

Running a heroin laboratory requires payments to whoever controls the territory—in most cases a local strongman, a government official, or the Taliban. Importing precursors requires bribing border guards (perhaps on both sides of the border) or paying an armed group for a covert escort. Smuggling the opium, morphine, or heroin out of Afghanistan requires access to an airfield or border crossing (controlled by the border police and Ariana Airlines, both of whose employees are reported to make significant income from drug trafficking),21 the escort of armed groups (Taliban, tribes, commanders), or specialists in packaging such as those who seal heroin inside licit commodities for export. The bureaucratic, military, political, or social superiors of those directly involved in facilitating trafficking claim a right to shares of the resulting tribute, though the higher the money moves, the less evident is its connection to the flowers whence it originated.

Opium and its derivatives are controlled substances under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, 1961, an international agreement administered by the International Narcotics Control Board (INBC) in Vienna. The INCB delegates its day-to-day work of monitoring and supporting compliance to UNODC. The convention was later supplemented by the 1988 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. The convention supports controlled use of narcotics for scientific and medical purposes. Each state party to the convention is obligated to enact national legislation to outlaw “Cultivation, production, manufacture, extraction, preparation, possession, offering, offering for sale, distribution, purchase, sale, delivery on any terms whatsoever, brokerage, dispatch, dispatch in transit, transport, importation and exportation of drugs contrary to the provisions of this Convention.”22

Conspiracy, preparation, or financial operations in connection with these acts must also be made criminal offenses. There is no provision in the convention for derogation from any of its provisions in times of armed conflict or emergency.

This regime mandates “counternarcotics” policies to prevent and punish the prohibited acts. But even though the enforcers use policy instruments in order to stop illicit use and transactions in narcotics, the effects of the instruments depend on how they structure incentives in the illegal narcotics market. Counternarcotics policy instruments intervene at various points of the value chain and thus affect prices, quantity, and the distribution of remaining profits differently. The strategy (combination and sequencing of tools) that lowers the physical supply of drugs the most is not necessarily the strategy that most effectively stops drug money from funding corruption and insurgency. Nor is it necessarily the strategy that improves security or creates stabilizing political alliances.

Eradication destroys some raw material produced by cultivators. Interdiction includes all interventions higher up in the value chain, such as arrests of traffickers, confiscation and destruction of drug contraband, interdiction of imports of precursor chemicals, destruction of heroin/morphine laboratories, removal from office or prosecution of officials corrupted by the trade, Security Council sanctions against travel and assets of traffickers under Resolution 1735, and measures to detect, prevent, and punish money laundering. “Alternative livelihoods” provide incentives to engage in licit activities rather than the narcotics industry. This includes incentive payments (such as the Good Performance Initiative) in return for reduction in or abstention from poppy cultivation. As discussed below, “alternative livelihoods” is a misnomer, as it implies a direct replacement of drug production by another activity, whereas a much more comprehensive development approach is needed. Afghanistan’s National Drug Control Strategy also includes pillars for institution building, law enforcement, public information, and regional cooperation, but these are all in support of the primary tools, eradication, interdiction, and alternative livelihoods.

Eradication is the destruction of the poppy crop in the field before harvest. It can be carried out manually, by knocking over the poppy stalks; mechanically, by crushing the crop under machinery; or with herbicides sprayed from either the ground or the air.23 Nearly all eradication in Afghanistan is done manually by Afghan security forces, sometimes supervised by U.S. private contractors. The Afghan government has rejected proposals by the United States to use herbicides, including aerial spraying, as has been done in Colombia, partly on the grounds that it will recall the alleged use of aerially delivered chemical weapons by the USSR in the early 1980s. Seventy-one percent of Afghans interviewed in a 2007 survey opposed or were uncertain about aerial spraying.24 Nonetheless, the U.S. Congress has for several years appropriated funds for the aerial eradication of opium poppy in Afghanistan. The U.S. Counternarcotics Strategy revives that proposal in careful language that nonetheless pressures the Afghan government to agree.

What effect does eradication have on the goals of counternarcotics? Eradication of the poppy crop has “forward” effects on the opiate value chain and “backward” effects on the rural population. The forward aim of eradication is to reduce drug money by reducing the amount of drugs, and the backward aim is to introduce more risk into the lives of the excessively secure Afghan cultivators so that they will plant other, less profitable crops. According to the National Drug Control Strategy of Afghanistan, the government will implement “targeted and verified eradication where alternative livelihoods are available,” but there is no definition of what this means or a mechanism to implement it; in practice it is largely ignored.

Even if eradication did sustainably decrease the amount of opium supplied by farmers to traffickers, the effect on total revenue would depend on how elastically the price shifts in response to changes in the quantity supplied. Does the price change so slowly that revenue decreases, or does the relatively inelastic demand for an addictive substance and the high risk premium that makes the cost of production irrelevant higher in the value chain mean that incremental eradication actually raises traders’ revenues? That no attempt has been made even to test this causal relationship indicates the intellectual bankruptcy of counternarcotics policy.

Both theoretical reasoning and empirical evidence indicate that any attainable amount of eradication (the current goal is 25 percent of the crop) is likely to increase drug revenue. Other things being equal, we would expect to see an increase in drug money, a rise in the cost of bribing eradicators, and a shift of income against those who cannot afford to bribe.25

Evidence from both the Taliban ban on cultivation in 2000–01 and from some localized decreases since then (especially Nangarhar in 2004–05) is consistent with this model. In 2001, when traders had little new product to resell or refine, their existing stocks increased in value, and sales continued. According to Omar Zakhilwal, president of the Afghanistan Investment Support Agency (who is both a Canadian-trained economist and a native of the poppy-producing Mohand area of Nangarhar province and in 2013 is minister of finance), opium traffickers were the main lobbyists for the ban with the Taliban leadership, as they wanted to increase the value of their inventories. Seizures of trafficked opiates across the border from Afghanistan in 2001 dropped by only 40 percent compared to the previous year, implying that trafficking continued from stocks at 60 percent of the previous volume but at a price several multiples larger, so that the higher prices led to an increase in revenue to the traders. There was no sign that the cultivation ban hurt the finances of the Taliban, who, like other power holders, benefited from the opium economy mainly by taxing traders, not farmers.

This example shows the effect of suppression of cultivation without interdiction of trafficking or alternative livelihoods efforts. An analysis that takes all of these into account is necessary to estimate the likely effect on narcotics revenue of different mixes of counternarcotics tools.

Eradication is one way to reduce the quantity of opium supplied to traders. Another method is a pre-planting campaign that successfully convinces, coerces, or encourages (bribes) cultivators not to plant opium poppy. The latter method has “succeeded” to various extents on at least five occasions: Helmand in 1988 and in 2002–03, the Taliban in 2000–01, Nangarhar in 2004–05, and Balkh in 2006–07. In several of these cases prices were also falling as a result of large stockpiles, and it is difficult to separate the effect of the price change from that of the policy.

In 1988, Mullah Nasim Akhundzada stopped poppy cultivation in Helmand in return for aid projects promised by the U.S. Embassy in Islamabad.26 Akhundzada was the most powerful mujahidin commander in Helmand. Because of objections by the U.S. Congress to negotiation with drug traffickers, the aid was not delivered. Mullah Nasim was assassinated, probably by traffickers to whom he had failed to deliver opium. Under his brother’s command, opium poppy cultivation resumed the next year.

In the fall of 2000, the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan issued a decree forbidding the cultivation of opium poppy throughout the territory under its control. Village headmen (maliks) were held responsible, and mullahs served as monitors. Cultivation was reduced by 95 percent. The price of raw opium rose tenfold, from $40–$60 per kilogram to $400–$600. The Taliban would probably not have been able to continue the cultivation ban at the higher prices, which meant that many cultivators’ debts denominated in opium quantities went up 1,000 percent. The escalating indebtedness created unstoppable pressure for more planting, which indeed occurred in the fall of 2001, even before the fall of the Taliban. Making a virtue of necessity, Mullah Umar rescinded the ban.

In 2002, the governor of Helmand, Sher Muhammad Akhundzada, nephew of Mullah Nasim, succeeded in decreasing cultivation by almost 50 percent.27 In the absence of security and development, production rebounded the following year and has now surpassed all records.

In 2004, Hajji Din Muhammad, a former mujahidin leader, used his tribal influence and the promise of massive U.S. aid (backed up by visits from U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad) to obtain a 95 percent reduction in cultivation in Nangarhar. Cultivators largely sustained this reduction in areas close to Jalalabad, where they could market other horticultural crops with the help of alternative livelihood programs, but in the absence of effective aid delivery elsewhere, cultivation rebounded in the more isolated areas of the province. This year [2007–08] production appears to have decreased again, but it is impossible to tell at this point to what extent this is due to counternarcotics efforts and to what extent to the drop in opium prices caused by last year’s record crop in Helmand.

In 2006, Muhammad Atta, governor of Balkh and a former mujahidin commander allied with Ahmad Shah Massoud, used his considerable influence and power to persuade the rural communities of Balkh not to plant opium. A year later, Governor Atta complained that the international community had not fulfilled its promises of aid and said he could not repeat the effort. If poppy cultivation in Balkh does not rebound in 2007–08, it will be because the summer marijuana crop may have off set the losses in income due to the poppy ban.28 Nonetheless, the low prices may prevent a full-scale rebound.

Eradication promotes the geographic spread of cultivation. Farmers in the remote province of Ghor for the first time found poppy farming profitable after the Taliban ban raised the price.29 In 2004–05, the traffickers based in Nangarhar sent financial and extension agents to other areas (including Balkh) to ensure an adequate supply of raw material from other areas. Hence the 2005 harvest had the largest geographical distribution of any year.

Eradication or coerced reductions do not sustainably reduce cultivation, because Afghan peasants do not plant opium poppy out of greed. They do so out of insecurity. In these insecure conditions the opium industry is the only entity supplying the public goods needed for agriculture such as credit, marketing, extension services, and guaranteed access to land. Rural communities (not just farmers) need the capacity to invest and work in other activities (not just to plant other crops) to earn incomes.

Many farmers finance cultivation (with its high labor and other costs) and food consumption during the winter by selling opium to traders before planting on futures contracts, called salaam. For most of the past decade, traders advanced to farmers about half of the price at harvest time of the amount contracted. For example, a farmer who made a salaam contract for 10 kilograms in the fall planting season of 2000, when opium was selling at about $40/kg, would have been paid $200. If he produced more than 10 kilos, he could sell the rest at the harvest price or keep it as inventory. If he produced less, he would owe the balance in cash at the harvest price, which he might pay, if he could, or roll over as debt to be paid off with opium from the next growing season.

Thus in the spring of 2001, the farmer who had contracted for 10 kilograms—which he was unable to produce because of the Taliban ban—would still owe the 10 kilos of opium, but now at the new price of nearly $400/kg. So the farmer would owe $4,000 to pay back a $200 loan. Given these debt burdens, it is no surprise that farmers rushed to plant opium in the fall of 2001.

The salaam system shifts the risk of eradication to the farmers, especially the poor, and makes it more difficult for them to adjust to eradication by planting crops with which they cannot pay off their opium debt. According to David Mansfield, the world’s leading researcher on the opium economy in Afghanistan, in response to the risk of eradication traders and money lenders were advancing only about 30 rather than 50 percent of the market value at planting time in 2006 for salaam contracts, further shifting risk to the cultivator. Even when poppy is eradicated on land belonging to a large landowner, it is likely that the landowner has rented the land to sharecroppers to whom he has advanced salaam contracts. The sharecroppers’ debts stand even if the crop is eradicated, and they stand to lose more than the landowner, who retains his claim on their assets. U.S. officials who claim that aerial spraying or other methods of forced eradication would enable them to be more evenhanded by eradicating crops of large landowners are ignoring how Afghan rural society actually works.

Afghan poppy-farming communities try to manage or reduce the risk posed to their livelihood by crop eradication. Thus far they have done so by adopting alternative crops only in those few areas, such as the districts around Jalalabad, where the market is developed enough that they can sell other products, mainly fruits and vegetables, to traders on futures contracts. Since these conditions exist in only a few areas, the main tools used to manage the risk are (1) bribery or political influence to halt eradication or divert it elsewhere, (2) emigration to Pakistan (the only available tactic during the Taliban ban in 2000–01), and (3) armed resistance.

Afghan farmers in most areas will choose legal livelihoods without eradication once they are confident that the alternatives will work. As long as they lack that confidence, they will respond to eradication with evasion or resistance. The more forcible the eradication, the more likely they are to turn to resistance. According to UNODC, “In 2007,” there was “much more resistance to eradication than in 2006,” with nineteen deaths (fifteen police and four farmers) and thirty-one people injured.30

Rural communities themselves must be consulted about whether they are in a position to meet their basic needs without recourse to poppy cultivation. The risk-averse Afghan farmer and the foreign official under pressure from the U.S. Congress or a parliament to show quick results have different definitions of when viable alternatives to poppy cultivation are available. Introducing eradication when foreigners claim alternatives are available, but before farmers feel secure in the alternatives, has led farmers in some areas to call upon the Taliban to protect them and to take up arms to prevent eradication teams from entering their areas. Teams from the U.S.- funded Alternative Livelihood Program, seen (rightly) as part of the same counternarcotics package, also cannot obtain access to many communities. Road-building teams are also attacked for fear that they will improve access for crop eradication.

More forcible eradication at this time, when both interdiction and “alternative livelihoods” are barely beginning, will increase the economic value of the opium economy, spread cultivation back to areas of the country that have eliminated or reduced it, and drive more communities into the arms of the Taliban.31

The basic idea of “alternative livelihoods” is sound: participation in the narcotics industry fulfills economic and social needs, the legitimate satisfaction of which is difficult under current circumstances, and those engaging in these activities need legitimate alternatives. Designers of “alternative livelihood” programs, however, often misunderstand and underestimate the functions of the narcotics industry. Many confuse alternative livelihoods with “crop substitution,” as expressed in the common question, “What other crop can they grow?” This question wrongly assumes that the sole noncriminal beneficiaries of the opium economy are “farmers” (who are presumed to cultivate their own land with mostly family labor), that the main reason “farmers” grow poppy is to increase their income, that there are no economic functions of the drug economy outside of cultivation, and that the only substitute for these functions is another “crop.”32

All of these assumptions are wrong. Opium is not a crop but an industry. The statement made by UNODC and echoed by the U.S. that “only” 14 percent—one-seventh—of the Afghan population is directly involved in opium cultivation ignores the fact, also documented by UNODC, that “cultivation” generates only 20–30% of the export value of the opiates produced in Afghanistan. It also disregards the fact that a very large number of people are directly involved in sectors of the opium economy other than cultivation and that many people gain their livelihoods from activities generated indirectly from demand created by the opium economy in, for instance, construction and trade.

The reduction in poppy cultivation in Nangarhar province in 2004–05 provided a test of the substantial macroeconomic impact of the drug economy. The ban had an impact on a variety of socioeconomic groups beyond opium farmers. Rural laborers who owned no land but were hired during the weeding and harvesting season are estimated to have lost as much as U.S. $1,000 in off-farm income as a result of the ban. The contraction of income among the rural population significantly reduced their purchasing power, halving the turnover of businessmen and shopkeepers in provincial and district markets. Unskilled daily wage laborers in the provincial capital of Jalalabad experienced both a reduction in daily wages and the number of days they were hired.33

The greatest impact of the ban was felt by opium poppy cultivating households, but those in areas with better access to resources fared better. Because of the ban, households with larger and well-irrigated landholdings encountered greater loss of on-farm income, but access to the agricultural commodity markets in Jalalabad enabled them to compensate for some of these losses by increasing cultivation of other high-value crops. Where possible, households also increased the number of family members engaged in daily wage labor. Thus, although the macroeconomic impact on comparatively resource-rich households was substantial, requiring reduced expenditure on basic food items, this group was generally able to avoid selling off both longer-term productive assets such as livestock and land, and investments generating licit income.

“In contrast,” observes Mansfield:

Those households most dependent on opium poppy and who typically cultivated it most intensively were found to adopt coping strategies in response to the ban that not only highlighted their growing vulnerability but threatened their long-term capacity to move out of illicit drug crop cultivation. The loss in on-farm income that this group experienced was not offset even in part by an increase in cultivation of high-value licit crops. This was due to constraints on irrigated land, the distance to markets, and the increasing control “local officials” had gained over the trade in licit goods. Instead, these households replaced opium poppy with wheat. However, due to land shortages and the density of population, wheat production was typically insufficient even to meet the household’s basic food requirements. The loss in off-farm income during the opium poppy weeding and harvesting seasons (up to five months’ employment) could not be replaced by intermittent wage labour opportunities paid at less than half the daily rate offered during the opium poppy harvest the previous year.34

Among members of the resource-poor group, the inability to pay existing debts threatened access to new loans. With no alternative income streams, households were forced to reduce expenditures on basic food items, withdraw children from higher education, and sell off livestock, household items, and investments in the licit economy. The resource-poor were also more likely than their better-off counterparts to send family members to Pakistan in search of employment. According to Mansfield, in some households the ban was felt so severely that even sole male members of working age were forced to leave in search of wage labor.35 Moreover, it was the relatively poor households that vehemently opposed both the Afghan government and foreign countries assumed to be responsible for the ban.36

This real-life experiment underscores the significant economic damage to the poorest of Afghan poppy farmers—and the resulting loss of support for the government—when cultivation was suppressed. The development component of counternarcotics policy should help communities and households participate in alternative activities that meet the needs identified in this study. To be effective among the poor who are most dependent on opium poppy cultivation, investments in rural livelihoods must precede coerced reduction in cultivation or eradication. Otherwise poor farmers will not be able to benefit from the programs.

Alternative livelihood programs should be guided by the following findings. First, poppy cultivation is not a choice of crop that requires another crop to substitute for lost income; it is a component of livelihood strategies of extended families. These strategies include labor migration, education, wage labor, and serving in armed groups. This multidimensional function of poppy cultivation is the reason for the use of the term alternative “livelihood” rather than “crop.”

The multiple functions of poppy cultivation in livelihood strategies refute the claims of advocates of eradication: that since no other crop produces the same gross income, eradication is necessary to force farmers to adopt other crops. Poppy cultivation fills needs that can be met by nonfarm activity. Furthermore, even cultivators who want to shift out of narcotics cannot do so without assistance. Eliminating cultivation before investing in assets needed for production actually deprives poor farmers of the capacity to adopt other crops and economic activities. Rural families do not need just another “crop.” They need access to opportunities and assets that enable them to support themselves without poppy cultivation. These opportunities can come in forms other than “crops.”

Secure employment is the most reliable “alternative livelihood.” This is supported by the Charney survey data, which found that of ten proposed means for convincing farmers not to grow opium next season, eradication was the least likely to work. The most effective means for reducing opium cultivation were identified as financial (income support to farmers, access to low-interest credit, and cash advances) and agricultural (seeds and water) rather than coercion.37

Second, poppy does not provide access only to income but also to credit, land, water, food security, extension service, and insurance. As the Afghan public sector, both national and local, was destroyed by the past decades of war, private and sometimes criminal groups undertook the provision of public goods. This included collective violence for “security,” in order to create conditions for their activities. Of course, when public goods are provided by private for-profit organizations without legal oversight, the provision is flawed (as the example of private security contractors in Afghanistan and Iraq shows). The opium industry privatized the provision of essential support services to the agricultural sector, as its rate of profit and global size made it the only industry with the resources and incentives to supply such public goods.

Third, the direct involvement of an estimated one-seventh of the Afghan population in opium poppy cultivation demonstrates that it is not a marginal activity. On the contrary, it signals a social revolution. For the first time in history, a substantial portion of the Afghan rural population is involved in the production of a cash crop for the global market. Never having come under direct colonial rule, and being distant and isolated from global markets over the past several centuries, Afghanistan’s people never experienced the commercial penetration of their society as seen in colonized countries. The country never produced tea, coffee, sugar, indigo, rubber, copper, diamonds, gold, oil, jute, or any of the other commodities whose cultivation on plantations or extraction from mines led to new forms of labor control and migration, followed by social and political upheavals. Only Afghanistan’s recent comparative advantage in the production of illegality and insecurity enabled it to join the global market by producing illicit crops. Hence, the economic alternatives to the opium economy must include, as the World Bank’s William Byrd stated, the creation of “labor intensive agriculture exports of high-value added,” not a return to subsistence farming.38 This is what the Interim Afghanistan National Development Strategy calls for: “The ideal type of agricultural activity for Afghanistan is labor-intensive production of high-value horticultural crops that can be processed and packaged into durable high-value, low-volume commodities whose quality and cost would be adequate for sale in Afghan cities or export to regional or world markets.”39

When USAID started the Alternative Livelihood Program in 2004, however, the initial package consisted of donations of wheat seed and fertilizer, much of which the farmers immediately sold to pay off their opium debts.

Fourth, the public goods and effective demand created by the opium industry in this predominantly rural and agricultural country have become central to macroeconomic stability. This is not the case in drug producing countries where cultivation involves a negligible part of the economy and a marginalized part of the population located in border areas. Even in Colombia, the value of narcotics production is estimated at only 3–4 percent of the GDP. In Afghanistan, nearly a third of the economy and probably an equal percentage of the population depends economically on the opium economy. Drug production affects not just farm income. It affects the balance of payments, tax revenues (through imports), the rate of exchange, employment, retail turnover, and construction.

The broad scope of the effects of the drug economy in Afghanistan led the current U.S. Strategy to refer to “alternative development,” rather than “alternative livelihoods.” As with other improvements in analysis and terminology in this report, however, the Strategy fails to draw the logical conclusions: that counternarcotics in Afghanistan requires a macroeconomic and political strategy over a period of decades, not a quick-fix based on accelerated eradication.

Fifth, since drugs are not marginal in Afghanistan, and changes in production and trafficking have significant macroeconomic impact, counternarcotics policy has national political impact. “Alternative livelihood” programs directed to regions in proportion to their volume of opium production generate perverse results: they become incentives to production of opium elsewhere. Just as eradication spreads poppy cultivation to new insecure areas with lower yields or a higher cost of eradication by raising the price, alternative livelihoods directed at opium cultivating areas spread cultivation by acting as an incentive, raising the expected returns to poppy cultivation. In the fall of 2004, an elder of the Mohmand tribe from Nangarhar told one of the authors that the people in his area were saying that they had to grow poppy in order to get assistance from the government. When this author told a U.S. senior official that livelihood programs should therefore be targeted at areas that were not growing poppy, he was told that he was “not living in the real world.” The current strategy responds to this with a program of incentives for “good performers.” Recognizing the problem is a positive step, one that demonstrates a shift in thinking since 2004 but is insufficient by itself, as discussed later.

Alternative development for counternarcotics must start from macroeconomic plans to create employment by linking Afghanistan to licit international markets, especially through rural industries based on agricultural products. Since elimination of the narcotics sector risks causing a significant economic contraction of one of the poorest and most-armed countries in the world, planning for elimination of narcotics must start from a political and macroeconomic plan to ensure stability and overall growth; it must integrate counterinsurgency, peace building, and development with counternarcotics as part of a national strategy, precisely as called for in the Afghanistan Compact.

Securing Afghanistan’s Future (SAF), the 2004 study prepared under the direction of Finance Minister Ashraf Ghani, proposed such a basic framework, though much more work was required, and those estimates are now out of date.40 SAF estimated that to eliminate the narcotics economy in fifteen years without compromising a modest rise in standards of living would require a minimum real growth rate of 9 percent per year in the licit economy. The growth rate alone would not cushion the shock sufficiently, as the losses from eliminating narcotics might not occur in the same locations and social groups as the new growth; therefore, sectoral and redistributive policies would also be needed. The I-ANDS also referred to this target, but there has been no further work on the integration of counternarcotics into macroeconomic planning. Instead the development component has been limited to small-scale rural development.

Sectoral policies might have to address particular commodities. As Ghani has noted, cotton (the original cash crop produced in the irrigated areas of Helmand) is not competitive with opium poppy as long as U.S. and European Union producers drive down the price by dumping subsidized cotton on the international market. Estimates of the price impact of these subsidies vary.41 Total U.S. cotton subsidies total more than $3 billion yearly, more than total U.S. development aid to Afghanistan.42

If the U.S. and EU subsidies cannot be eliminated due to pressure from domestic political constituencies, subsidies could still be provided in Afghanistan.43 In meetings with counternarcotics officials, Helmand farmers have asked for government cotton subsidies as an incentive to shift from poppy to cotton, which used to be grown on irrigated land there, but so far Helmand farmers do not qualify for exemptions from the discipline of the “free” market. Even if cotton alone is not competitive, Ghani has suggested that textile and garment production would be competitive. Establishing textile quotas for Afghanistan in major markets and investing in simple garment factories in Afghan cotton-producing areas could increase employment. The appeal of a certified “Made in Afghanistan” (or “Made in Afghanistan by Afghan women”) label could off set the increased costs of production and transport. This is just one example: creating markets for Afghan products and providing marketing assistance is key to alternative development. Should subsidies prove impractical under Afghan conditions, another approach is to expand local procurement by the international community in Afghanistan combined with attempts to encourage contract growing of high-value horticulture.44

Moving rural Afghanistan into the licit economy requires investment in many kinds of public goods: roads, security, credit, marketing, storage, extension service, and the creation of rural industries as well. All of this depends in turn on linking Afghanistan to regional and global markets and ensuring access to those markets. This requires political and business initiatives at the policy level. The U.S. State Department is soliciting proposals under their new Economic Empowerment in Strategic Regions (EESR) program to provide alternative income generation for farmers in southwestern Afghanistan through production and processing of agricultural fibers, oilseeds, and feed products. But USAID reportedly refuses to fund such initiatives on the grounds that they conflict with the Bumpers Amendment.45 Until there is an official declaration of administration policy regarding the amendment, those qualified to submit proposals will be reluctant to do so.

Avoiding the perverse incentives generated by Alternative Livelihood Programs targeted at poppy-growing areas requires more than the Good Performance Fund, which rewards provinces that refrain from or reduce opium poppy cultivation by providing development funds to the governors. The concept of rewarding areas and communities for efforts against poppy is a good one, as it creates the right incentives. Making funds available to governors, however, may not be the most effective way to do so. In the Afghan state system, governors have limited power and virtually no budgetary or expenditure authority. The idea of rewarding governors appears to have developed from observation of provinces where governors with a great deal of personal influence because of their tribal or mujahid background managed to reduce poppy cultivation. These governors were able to do so, however, because of their personal power networks and links with the drug trade, not because of the powers of the governor’s office.

It might be more effective to target such incentives to communities through programs organized like the National Solidarity Program, which provides block grants to community councils to carry out development projects chosen by the communities themselves. The Independent Directorate for Local Governance (IDLG) in the office of the president is developing plans for the reintegration of communities into the national and provincial administration and state structure through long-term agreements between the state and communities. These agreements may include measures for the gradual elimination of poppy cultivation and trafficking as part of a package of public services provided. Experience has shown that tying aid closely to reductions in cultivation does not give a sustainable counternarcotics outcome, but linking communities to the state through public services does create capacities for monitoring and incentives to comply. This subnational approach to incentives could work better than one solely focused on governors.

The IDLG program provides for gradual reduction of cultivation, where it exists. Such transitional measures are essential. Farmers cannot reasonably be expected to abandon a pivotal part of their livelihood strategy as soon as a foreign government official decides that they have alternative livelihoods (perhaps because an office called “Alternative Livelihoods Program” has been established in the province). The risk-averse Afghan peasant and the foreign official under pressure from a capital to show quick results have differing definitions of when alternatives to poppy cultivation are available.

Management of this risk during the transition to alternative livelihoods poses a challenge to counternarcotics policy. One example courtesy of Mansfield: an aid organization provided funding to enable farmers in Kandahar to plant fruit trees. The farmers planted the trees in their poppy fields and continued to grow poppy among the saplings. As the trees matured over several years, their shade would prevent the poppy from growing, while their increasing yield of fruit would provide cash income as well as advance payments from traders in due course. By growing poppy the farmers could still earn a return on their land while the trees were maturing. Both farmer and development practioners saw this process as a rational way to manage the transition from opium to another crop (and other cropping options could be seen as part of the transition in other parts of the country). However, those involved in drug control saw this as unacceptable and argued that now that farmers were in receipt of assistance and growing other crops they should cease their opium poppy cultivation immediately. They suggested the aid should be ceased and made conditional on the elimination of opium poppy even though farmers were not yet gaining an income from the new crop they had planted. These drug controllers failed to recognize that there is an inevitable process of diversifying into other activities and only gradually abandoning poppy as farmers develop greater confidence in other economic activities.46

The current counternarcotics strategy has no explicit plan for managing the transition, sequencing the different policy tools, or building the state institutions simultaneously with trying to use them. These are, however, the key questions for counternarcotics strategy. The one exception is the statement that eradication should be carried out “where access to alternative livelihoods is available,” a principle with no mechanism for implementation.

Several policy instruments address higher parts of the value chain.

Interdiction of the trade: mainly destruction of the product, including raids on opium bazaars, police seizures of drugs found in vehicles or in storage, and destruction of heroin or morphine laboratories. Though these actions are carried out by law enforcement institutions, they entail more enforcement than law. Once a banned substance is seized, the government can destroy it without additional legal procedure or referral to a court. Needless to say, this is not what always happens. There is a system for how much traffickers must pay the police to recover a portion of their goods. Instead of destroying the captured substance, Afghan police sometimes claim they have to transport it to their superiors for “evidence.” What happens to it afterward is not always well documented.47

Arrest of traffickers: the number of such cases is on the rise according to the U.S. Strategy, but such arrests mainly target small traffickers or smugglers.48 The incapacity and corruption of the Afghan justice system is such that few of the reported 562 arrests and prosecutions lead to fair trial and conviction. Instead arrests lead to detention and bribery for release. In response, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) is working to compile cases against major traffickers that can be presented for extradition to the United States. The total number of such cases so far is only two or three and cannot increase quickly enough to have any appreciable impact on the largest sector of the. Afghan economy.49

Arrests of corrupt officials: such arrests are rare in the extreme, since the police and courts are the main object centers of corruption. Although officials of the National Directorate of Security (NDS), the intelligence agency, have allegedly been arrested, tried, and punished for accepting bribes from traffickers, we are not aware of any such prosecutions in the Ministry of the Interior.

Building institutions for interdiction and law enforcement: just as foreign donors have supported the formation of the Central Poppy Eradication Force (CPEF), they have also supported the formation of the Counternarcotics Police Force (CNPF) for interdiction and law enforcement. The United States is also supporting the creation of special prosecutors, courts, and prisons for drug offenses. These institutions will be resourced and trained better than the rest of the Afghan justice system, since foreigners think they are important.

Measures against money laundering: these are not mentioned in the public version of the U.S. Counternarcotics Strategy, but they are reportedly part of the classified version. A World Bank–UNODC study of money laundering for drug trafficking in Afghanistan estimated (very approximately) that in 2004–05 actors in the opium economy imported $1.7 billion into Afghanistan using the informal hawala system of money transfer.50 The author of the study could not estimate the amount of drug profits transferred out of Afghanistan in the same way, but it is likely of the same order of magnitude.

Removal from or prevention of the appointment to senior positions of officials suspected of drug-related corruption: all ministers and senior officials of the government serve at the pleasure of the president and may (in principle if not in practice) be removed from office at his discretion. Hence counternarcotics policy is closely related to the benchmark in the Afghanistan Compact requiring that “A clear and transparent national appointments mechanism will be established … for all senior level appointments to the central government and the judiciary, as well as for provincial governors, chiefs of police, district administrators and provincial heads of security.”51

Interdiction also includes measures for strengthening institutions through funding, equipment, and training. Properly designed, implemented, and sequenced, these are needed components of a counternarcotics policy. But they cannot succeed without building a state to implement the policies and exercise command and control over the strengthened institutions.

Interdiction that is implemented fairly and effectively would directly contribute to the goals of the Afghanistan Compact. No study has estimated the varying effects of different types of interdiction on the narcotics value chain, but the World Bank argues that interdiction would lower the farmgate price of opium.52 By raising the cost of trafficking, interdiction would lower the demand curve of traffickers. It would reduce the demand for opium, thus making poppy cultivation less attractive and rendering legal livelihoods more competitive, and it would do so invisibly over the entire opium market, without the political discrimination that eradication entails.

Harjit Sajjan, a reserve major in the Canadian Army, observed the contrasting political effects of interdiction and eradication while serving with the Canadian NATO deployment in Kandahar:

Interdiction is the key. Eradication impacts the farmers who are trying to feed their families but interdiction impacts the drug lords, or what the local Afghans call “Dhakoos” (Bandits). The emphasis should be against the drug labs and transportation routes. This interdiction method is more efficient and has greater impact on the drug lords. Plus, it does not disrupt the farmers. This will allow the International agencies, NGOs, and military time to work on alternative programs.53

The political risk of trying to implement interdiction under current conditions is that it is more likely to concentrate and integrate the opium industry than to destroy it. As the state lacks autonomy from power holders, the latter compete to gain control over the foreign-funded counternarcotics programs to use them against rivals. Control over interdiction can be a powerful tool for crushing competitors.54

Hence without the necessary political institutions, international training and funding does not have the desired results. Training teaches people and institutions how to accomplish a mission; it cannot make them loyal or committed to risking their lives or fortunes for that mission. It is not possible to create effective institutions for counternarcotics enforcement when such a high proportion of a society’s power holders are directly or indirectly beholden to the drug trade and can see no way to move out of it. A political solution and transitional arrangement for the upper end of the drug value chain is as essential as a political solution for the insurgency.