Bakkerij Paul Année

The best wholegrain and sourdough breads in town, bar none, all made from organic grains.

The Grachtengordel, or “girdle of canals”, reaches right round the city centre and is without doubt the most charming part of Amsterdam, its lattice of olive-green waterways and dinky humpback bridges overlooked by street upon street of handsome seventeenth-century canal houses. It’s a subtle cityscape – full of surprises, with a bizarre carving here, an unusual facade there, but it is the district’s overall atmosphere that appeals rather than any specific sight, with the exception of the Anne Frank Huis. There’s no obvious walking route around the Grachtengordel, and you may prefer to wander around as the mood takes you, but the description we’ve given below goes from north to south, taking in all the highlights on the way. On all three of the main canals – Herengracht, Keizersgracht and Prinsengracht – street numbers begin in the north and increase as you go south.

Running east to west along the northern edge of the three main canals is leafy, memorably picturesque Brouwersgracht. Originally, Brouwersgracht lay at the edge of Amsterdam’s great harbour with easy access to the sea. This was where ships returning from the East unloaded their silks and spices and breweries flourished here too, capitalizing on their ready access to shipments of fresh water. Today, the harbour bustle has moved elsewhere, and the warehouses, with their distinctive spout-neck gables and shuttered windows, formerly used for the delivery and dispatch of goods by pulley from the canal below, have been converted into ritzy apartments that have proved particularly attractive to actors and film producers. There are handsome merchants’ houses here as well, plus moored houseboats and a string of quaint little swing bridges. Restaurants have sprung up here too, including one of the city’s best, De Belhamel.

On the east side of Prinsengracht, opposite the large and conspicuous Noorderkerk, this brown-brick courtyard was built as an almshouse in 1804 to the order of a certain Aernout van Brienen. A well-to-do merchant, Van Brienen had locked himself in his own strongroom by accident and, in a panic, he vowed to build a hofje if he was rescued: he was and he did. The plaque inside the complex doesn’t give much of the game away, inscribed demurely with “For the relief and shelter of those in need.”

Leliegracht leads left off Prinsengracht, and is one of the tiny radial canals that cut across the Grachtengordel. It holds one of the city’s finest Art Nouveau buildings, a tall and striking building at the Leliegracht-Keizersgracht junction designed by Gerrit van Arkel in 1905. It was originally the headquarters of a life insurance company – hence the two mosaics with angels recommending policies to bemused earthlings.

Prinsengracht 263

![]() 020/556 7100

020/556 7100

Daily: mid-March to June & early Sept 9am–9pm, Sat until 10pm; July & Aug 9am–10pm; mid-Sept to mid-March 9am–7pm

closed Yom Kippur

€8.50, 10- to 17-year-olds €4, under-9s free

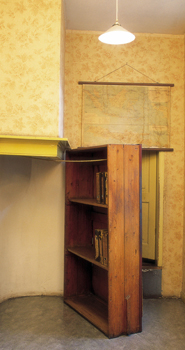

Easily the city’s most visited sight, the Anne Frank Huis is where the young diarist and her family hid from the Germans during World War II. Since the posthumous publication of her diaries, Anne Frank has become extraordinarily famous, in the first instance for recording the iniquities of the Holocaust, and latterly as a symbol of the fight against oppression and in particular racism. The family spent over two years in hiding here, but were eventually betrayed and dispatched to Westerbork – the transit camp in the north of the country where most Dutch Jews were processed before being moved to Belsen or Auschwitz. Of the eight souls hidden in the annexe, only Otto Frank survived; Anne and her sister died of typhus within a short time of each other in Belsen, just one week before the German surrender.

Anne Frank’s diary was among the few things left behind in the annexe. It was retrieved by one of the people who had helped the Franks and handed to Anne’s father on his return from Auschwitz; he later decided to publish it. Since its appearance in 1947, it has been constantly in print and has sold millions of copies.

Despite being so popular, the house has managed to preserve a sense of intimacy, a poignant witness to the personal nature of the Franks’ sufferings. The rooms the Franks occupied for two years have been left much the same as they were during the war albeit without the furniture – down to the movie star pin-ups in Anne’s bedroom and the marks on the wall recording the children’s heights. Video clips of the family in particular and the Holocaust in general give the background. Anne Frank was one of about 100,000 Dutch Jews who died during World War II, but this, her final home, provides one of the most enduring testaments to its horrors.

Trapped in her house, Anne Frank liked to listen to the bells of the Westerkerk, just along Prinsengracht, until they were taken away to be melted down for the German war effort. The church still dominates the district, its 85-metre tower (April–Oct Mon–Sat 10am–5.30pm €6) – without question Amsterdam’s finest – soaring graciously above its surroundings. The church was designed by Hendrick de Keyser and completed in 1631 as part of the general enlargement of the city, but whereas the exterior is all studied elegance, the interior is bare and plain.

Westermarkt, an open square in the shadow of the Westerkerk, possesses two evocative memorials. At the back of the church, beside Keizersgracht, are the three pink granite triangles (one each for the past, present and future) of the Homomonument, the world’s first memorial to persecuted gays and lesbians, commemorating all those who died at the hands of the Nazis. It was designed by Karin Daan and recalls the pink triangles the Germans made homosexuals sew onto their clothes during World War II.

Nearby, on the south side of the church by Prinsengracht, is a small but beautifully crafted statue of Anne Frank by the modern Dutch sculptor Mari Andriessen.

A brief walk from the Westermarkt, the Huis Bartolotti boasts a flashy facade of red brick and stone dotted with urns and columns, faces and shells. The house is an excellent illustration of the Dutch Renaissance style, much more ornate than the typical Amsterdam canal house. The architect was Hendrick de Keyser and a director of the West India Company, Willem van den Heuvel, footed the bill. Van den Heuvel inherited a fortune from his Italian uncle and changed his name in his honour to Bartolotti – hence the name of the house.

Between Westermarkt and Leidsegracht, the main canals are intercepted by a trio of cross-streets, which are themselves divided into shorter streets, collectively known as “Nine Streets”, mostly named after animals whose pelts were once used in the district’s tanning industry. There’s Reestraat (Deer Street), Hartenstraat (Hart), Berenstraat (Bear) and Wolvenstraat (Wolf), not to mention Huidenstraat (Street of Hides) and Runstraat – a “run” being a bark used in tanning. The tanners are long gone and today these are eminently appealing shopping streets, known as De Negen Straatjes (The Nine Streets).

Keizersgracht 324

A Neoclassical monolith of 1787, this mansion was built to house the artistic and scientific activities of the eponymous society, which was the cultural focus of the city’s upper crust for nearly a hundred years. Dutch cultural aspirations did not, however, impress everyone. It’s said that when Napoleon visited the city the entire building was redecorated for his reception, only to have him stalk out in disgust, claiming that the place stank of tobacco. Oddly enough, it later became the headquarters of the Dutch Communist Party, but they sold it to the council who now lease it to the Felix Meritis Foundation for experimental and avant-garde art workshops, conferences, discussions and debates.

The graceful and commanding Cromhouthuizen, at Herengracht 364–370, consist of four matching stone mansions, built in the 1660s for one of Amsterdam’s wealthy merchant families, the Cromhouts, and two of them now house the Bijbels Museum. This contains a splendid selection of old Bibles, including the first Dutch-language Bible ever printed, dating from 1477, and a series of idiosyncratic models of Solomon’s Temple and the Jewish Tabernacle, plus a scattering of archeological finds from Palestine and Egypt.

Lying on the edge of the Grachtengordel, Leidseplein is the bustling hub of Amsterdam’s nightlife, a rather cluttered and disorderly open space. The square once marked the end of the road in from Leiden and, as horse-drawn traffic was banned from the centre long ago, it was here that the Dutch left their horses and carts – a sort of equine car park. Today, it’s quite the opposite: continual traffic made up of trams, bikes, cars and pedestrians gives the place a frenetic feel, and the surrounding side streets are jammed with bars, restaurants and clubs in a bright jumble of jutting signs and neon lights. On a good night, Leidseplein can be Amsterdam at its carefree, exuberant best.

Leidseplein holds the grandiose Stadsschouwburg, a neo-Renaissance edifice dating from 1894, which was so widely criticized for its clumsy vulgarity that the city council of the day temporarily withheld the money for decorating the exterior. Home to the National Ballet and Opera until the Muziektheater was completed on Waterlooplein in 1986, it is now used for theatre, dance and music performances. It also functions as the spot where the Ajax football team gather on the balcony to wave to the crowds whenever they win anything, as they often do.

Heading northeast from Leidseplein, Leidsestraat is a crowded shopping street that leads across the three main canals up towards the Singel and the flower market. En route, at the corner of Keizersgracht, is the Metz & Co department store, which was, when it was built, the tallest commercial building in the city – one reason why the owners were able to entice Gerrit Rietveld, the leading architectural light of the De Stijl movement, to add a rooftop glass and metal showroom in 1933. The showroom has survived and is now a café offering one of the best views over the centre in this predominantly low-rise city.

South of Metz & Co, along Keizersgracht, is Nieuwe Spiegelstraat, an appealing mixture of bookshops and corner cafés that extends south into Spiegelgracht to form the Spiegelkwartier – home to the pricey end of Amsterdam’s antiques trade.

Nieuwe Spiegelstraat meets the elegant sweep of Herengracht near the west end of the so-called De Gouden Bocht (the Golden Bend), where the canal is overlooked by double-fronted mansions – some of the most opulent dwellings in the city. Most of these houses were remodelled in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Characteristically, they have double stairways leading to the entrance, underneath which the small door was for the servants, while up above, the majority of the houses are topped off by the ornamental cornices that were fashionable at the time. Classical references are common, both in form – pediments, columns and pilasters – and decoration, from scrolls and vases through to geometric patterns inspired by ancient Greece.

Stretching down Vijzelstraat from Herengracht is one of Amsterdam’s most incongruous buildings – you can’t possibly miss its looming, geometrical brickwork. Now home to the Stadsarchief, the state archives, it started out as the headquarters of a Dutch shipping company, the Nederlandsche Handelsmaatschappij, before falling into the hands of the ABN-AMRO bank, which was itself swallowed by a consortium led by the Royal Bank of Scotland in 2007. Dating to the 1920s, the building is known as De Bazel after the architect Karel de Bazel (1869–1923), whose devotion to theosophy – a combination of metaphysics and religious philosophy – formed and framed his design. Every facet of Bazel’s building reflects the theosophical desire for order and balance from the pink and yellow brickwork of the exterior (representing male and female respectively) to the repeated use of motifs drawn from the Middle East, the source of much of the cult’s spiritual inspiration. At the heart of the building is the Schatkamer (Treasury), an Art Deco extravagance that exhibits an intriguing selection of photographs and documents drawn from the city’s vast archives.

This delightful museum holds a superb collection of handbags, pouches, wallets, bags and purses from medieval times onwards, exhibited on three floors of a grand old mansion. The collection begins on the top floor with a curious miscellany of items from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. The next floor down focuses on the twentieth century, with several beautiful Art Nouveau handbags, while the final floor is given over to temporary displays.

Herengracht 605

![]() 020/523 1870

020/523 1870

Mon–Fri 10am–5pm, Sat & Sun 11am–5pm

€7

The coal-trading Holthuysen family occupied this elegant, mansion until the last of the line, Sandra Willet-Holthuysen, gifted her home and its contents to the city in 1895. The most striking room is the Blue Room, which has been returned to its original eighteenth-century Rococo appearance – a flashy and ornate style that the Dutch merchants regarded as the epitome of refinement and good taste. Other rooms have the more cluttered appearance of the nineteenth century and the house also displays a small collection of glass, silver, majolica and ceramics assembled by Sandra’s husband, Abraham Willet.

The Grachtengordel comes to an abrupt halt at the River Amstel. The Magere Brug (Skinny Bridge), spanning the Amstel at the end of Kerkstraat, is the most famous and arguably the cutest of the city’s many swing bridges. Legend has it that this bridge, which dates back to about 1670, replaced an even older and skinnier version, originally built by two sisters who lived on either side of the river and were fed up with having to walk so far to see each other.

The Amstelsluizen – or Amstel locks – are closed every night when the council begin the process of sluicing out the canals. A huge pumping station on an island out to the east of the city then starts to pump fresh water from the IJsselmeer into the canal system; similar locks on the west side of the city are left open for the surplus to flow into the IJ and, from there, out to sea. The watery content of the canals is thus regularly refreshed – though, despite this, and with three centuries of algae, prams, shopping trolleys and a few hundred rusty bikes, the water is only appealing as long as you’re not actually in it.

Doubling back from the Amstel Sluizen, turn left along the north side of Prinsengracht and you soon reach the Amstelveld, where the Monday flower market sells flowers and plants, and is much less of a scrum than the Bloemenmarkt. Adjacent Reguliersgracht is one of the three surviving radial canals that cut across the Grachtengordel, its dainty humpback bridges and sparkling waters overlooked by charming seventeenth- and eighteenth-century canal houses.

Located right on the canal, this four-storey museum of photography breathes history on the outside, but has a modern and industrial feel once you enter. FOAM aims to be a platform for both well-established photographers and young and upcoming talent, providing them with an opportunity to reach a larger audience. All genres of photography are covered and exhibitions are rotated regularly, with opening days often attracting hundreds of enthusiasts. Recent exhibitions have included the abstractions of Michael Wolf, the controversial Ari Marcopoulos and Cuny Janssen’s whimsical My Grandma was a Turtle.

The Museum Van Loon boasts the finest accessible canal house interior in Amsterdam. Built in 1672, and first occupied by the artist and pupil of Rembrandt, Ferdinand Bol, the house has been returned to something akin to its eighteenth-century appearance, with acres of wood panelling and fancy stucco work. Look out also for the ornate copper balustrade on the staircase, into which is worked the name “Van Hagen-Trip” (after a one-time owner of the house); the Van Loons later filled the spaces between the letters with iron curlicues to prevent their children falling through. The top-floor landing has several paintings sporting Roman figures, and one of the bedrooms – the “painted room” – is decorated with a Romantic painting of Italy, a favourite motif in Amsterdam from around 1750 to 1820. The oddest items are the fake bedroom doors: the eighteenth-century owners were so keen to avoid any lack of symmetry that they camouflaged the real bedroom doors and created imitation, decorative doors in the “correct” position instead.

One of the larger open spaces in the city centre, Rembrandtplein is a neat and trim open space that was formerly Amsterdam’s butter market. It was renamed in 1876, and is today one of the city’s nightlife centres, although its crowded restaurants and bars are firmly tourist-targeted. Rembrandt’s statue stands in the middle, his back wisely turned against the square’s worst excesses, though, to be fair, the Hotel Schiller, with its Art Deco flourishes, does provide some architectural flair.

Tiny Muntplein is dominated by the Munttoren, an imposing fifteenth-century tower that was once part of the old city wall. Later, the tower was adopted as the municipal mint – hence its name – and Hendrik de Keyser, in one of his last commissions, added a flashy spire in 1620. A few metres away, the floating Bloemenmarkt, or flower market (daily 9am–5pm some stalls close on Sun), extends along the southern bank of the Singel. Popular with locals and tourists alike, the market is one of the main suppliers of flowers to central Amsterdam, but its blooms and bulbs now share stall space with souvenir clogs, garden gnomes, Delftware and similar tat.

The canals of the Grachtengordel were dug in the seventeenth century in order to extend the boundaries of a city no longer able to accommodate its burgeoning population. Increasing the area of the city from two to seven square kilometres was a monumental task, and the conditions imposed by the council were strict. The three main waterways – Herengracht, Keizersgracht and Prinsengracht – were set aside for the residences and businesses of the richer and more influential Amsterdam merchants, while the radial cross-streets were reserved for more modest artisans’ homes; meanwhile, immigrants, newly arrived to cash in on Amsterdam’s booming economy, were assigned, albeit informally, the Jodenhoek (see The Old Jewish Quarter and Eastern Docklands) and the Jordaan. In the Grachtengordel, everyone, even the wealthiest merchant, had to comply with a set of detailed planning regulations. In particular, the council prescribed the size of each building plot – the frontage was set at thirty feet, the depth two hundred – and although there was a degree of tinkering, the end result was the loose conformity you can see today: tall, narrow residences, whose individualism is mainly restricted to the stylistic permutations amongst the gables.

The earliest gables, dating from the early seventeenth century, are the so-called crow-stepped gables, which were largely superseded by neck gables and bell gables, both named for the shape of the gable top. Some are embellished, some aren’t, many have decorative cornices and the fanciest – which mostly date from the eighteenth century – sport full-scale balustrades. The plainest gables belong to the warehouses, where deep-arched and shuttered windows line up on either side of the loft doors that were once used for loading and unloading goods winched by pulley from the street down below.

The best wholegrain and sourdough breads in town, bar none, all made from organic grains.

Sells books on – and by – leading Dutch artists and graphic designers, and entertaining postcards too.

A stalwart of the Amsterdam antiquarian book trade, Brinkman has lots of good local stuff with expert advice if and when you need it.

Holds a wonderful selection of Dutch tiles from the fifteenth century onwards; it also operates an online ordering service.

One of the larger secondhand stores, with everything from army jackets to hats, fur coats, shoes and belts. Specializes in the 1970s and 1980s.

Amsterdam is full of flower shops, but this one is the most imaginative and sensual. Bouquets to melt the hardest of hearts.

Famed antique lamp shop, with some wonderfully kitsch examples as well as offbeat new lamps and lights.

Friendly shop with a comprehensive selection of Dutch cheeses – much more than ordinary Edam – plus olives and international wines.

Good-quality secondhand clothes with the emphasis on assorted tackle from the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Strong on suits and vintage dresses.

Superb – and superbly creative – assortment of vintage clothing from dresses through to hats. Its forte is 1940s and 1950s gear.

Singel 184, junction of Oude Leliestraat

Mon noon–6pm, Tues–Sat 11am–6pm & Sun noon–5pm

Without doubt the best chocolatier in town, selling a wonderfully creative range of chocs in all sorts of shapes and sizes. This mini-chain has also abandoned the tweeness of the traditional chocolatier for brisk modern decor. Also at Staalstraat 17.

Amsterdam’s biggest and best bookshop. Six floors of absolutely everything and although most of the contents are in Dutch, there are good English sections too.

A jumble of bargain-basement glassware and crockery, candlesticks, antique tin toys, kitsch souvenirs, old apothecaries’ jars and flasks. Perfect for browsing.

The “White Teeth Shop” sells wacky toothbrushes and just about every dental hygiene accoutrement you could ever need.

The biggest and most famous of the coffeeshop chains, and a long way from its poky Red Light District-dive origins. This, the main Leidseplein branch (the Palace), housed in a former police station, has a large cocktail bar, coffeeshop, juice bar and souvenir shop, all with separate entrances. It’s big and brash, not at all the place for a quiet smoke, though the dope they sell (packaged up in neat little brand-labelled bags) is reliably good.

What used to be a hippie hangout, turned into a fresh and trendy coffeeshop with flatscreens on the walls, attracting a select clientele.

Very relaxed, very friendly, and worth a visit whether you want to smoke or not.

Essentially a gay coffeeshop (in Dutch, “the other side” is a euphemism for gay), but straight-friendly and the atmosphere is relaxed and good fun.

Just walking past will get your taste buds going: a serious treat for breakfast or lunch.

Small, English-style teashop in the basement of a canal house. Pies and sandwiches, pots of tea – and a decent breakfast.

Smashing restaurant where the Art Nouveau decor makes for a delightful setting and the menu is short but extremely well-chosen, mixing Dutch with French dishes. Main courses at around €20–25.

Something of an Amsterdam institution, the daily changing menu here features familiar vegan and vegetarian options, with organic beer to wash it down. Mains at around €15.

Top notch Italian restaurant with fresh ingredients. Everything is homemade, from the original Italian gelato to the pasta. Many wines per glass. Mains around €25, a bit less for pasta.

This much-lauded restaurant offers immaculately presented dishes from a well-chosen menu. The old fashioned interior adds to the homely feel. Main courses cost €23 and up, though you might prefer the three-course set menu instead. Has an excellent selection of wines, too.

Tiny but much-liked Indonesian restaurant with a friendly atmosphere, serving spicy dishes with mains hovering at around €20 and the traditional rijsttafel from €23.

Offers a substantial choice of Indochinese food, with both Vietnamese and Thai options. The subdued atmosphere suits the prices, with main courses averaging €25–30.

Laidback place with a little more soul than the average Amsterdam veggie joint. Pleasant, attentive service. No alcohol.

Exuberant flower power in this retro restaurant with old movies projected on the wall and cushions in every thinkable design. The menu is less adventurous, ranging from a simple hamburger to lobster, at reasonable prices.

Seafood restaurant with a well-considered menu, both set menus and à la carte, with mains around €23.

Atmospheric little place serving good-quality, simple cuisine with main courses averaging €24; there’s a good wine list too.

This cordial restaurant is kitted out with yellow tables and pastel walls embellished with Art Nouveau flourishes. The small but well-chosen menu offers Dutch/Mediterranean cuisine – the seafood is delicious. Mains from €20.

Located in the basement of an old canal house, this restaurant offers a mind-boggling range of fillings for its pancakes (around €9).

Informal French-Mediterranean restaurant with modern decor offering tasty dishes such coq au vin, bouillabaisse and red sea bass with couscous. Mains €22 and up.

Cosy split-level restaurant with sixteenth-century relics on the wall and a first-class menu offering classic dishes with a modern twist. Solely organic meat and fish in season. Mains from €23 and up.

Exceptionally good value Indonesian, on a street better known for rip-offs. Friendly and informed service preludes spectacular rijsttafels, both meat and vegetarian.

Cheerful little place offering Mediterranean cuisine with only the freshest of ingredients in an informal setting. Attractively located on the canal side.

Competent Indian restaurant in terms of quality and price, with a wide selection of dishes, all expertly prepared and moderately priced.

Lively and fashionable café annexe restaurant, popular with locals. Great sandwiches and salads at daytime and everything from duck to fresh oysters in the evening. Comfortable velvet lounge seats outside make it a great spot to linger.

Traditional French restaurant in an old and attractive canal house a short walk from Dam Square. Relaxed atmosphere and attentive service. Mains from around €24.

Slick and chic restaurant, with an excellent and enterprising French-inspired menu including such delights as poached lobster, smoked mackerel and beef cheek stew-stuffed ravioli. The selection of wines complements with vim and gusto.

Located right next to the Anne Frank Huis, this smart place offers flavoursome mains like pan-fried John Dory and venison stew for around €18. Turns into a lively place with DJs at night.

Huge and fashionable gay spot, with fluorescent pink lights and multiple bars. Cocktail nights and DJs on weekends. Also frequented by non-gays.

In a handsome old canal house, this bar boasts impressive wooden decor – from the longest of bars to the tall wood-and-glass cabinets – and specializes in Dutch beers, of which it has 130 varieties, twelve on tap.

Café with a laidback vibe. Popular for after-work drinks.

Stone-floored, neighbourhood bar-cum-off-licence that’s been owned by the same family for years. Kitted out in traditional style, it specializes in jenever (gin) with dozens of brands and varieties.

With its wood panelling, antique Delft tiles and ancient stove, this is one of the cosiest bars in the Grachtengordel, though it does get packed late at night with a garrulous crew.

Relaxed neighbourhood brown bar with rickety old furniture and a mini-terrace beside the canal.

With its well-worn decor and chatty atmosphere, this popular and lively brown bar offers a wide range of drinks and well-priced food, served 10am–10pm.

Café-bar with an arty air and brisk modern fittings. Tasty snacks and light meals plus an outside mini-terrace right on the canal. Lunch served daily 10am–4pm, evening meals 6–10pm.

Small, campy bar, patronized mostly, but not exclusively, by women and transvestites. Quiet during the week, it steams on the weekend.

A chic café-bar – cool, light and vehemently un-brown. The clientele is stylish, and the food is hybrid Mediterranean-Eastern. Breakfast in the garden during the summer is a highlight. Usually packed.

Popular local hangout attracting musicians, students and young professionals. Crowded at the weekends with a friendly and amenable crew.

Something of a phenomenon in Amsterdam, this rapid-fire improv comedy troupe hailing from the US performs at the Leidseplein Theater nightly to crowds of both tourists and locals alike. With inexpensive food, cocktails and beer served in pitchers, the comedy need not be funny – but it is.

Korte Leidsedwarsstraat 115

![]() 020/626 3249

020/626 3249

Daily 9pm–3am, Fri & Sat until 4am

It’s worth hunting down this legendary little jazz bar just off Leidseplein for its quality modern jazz. It’s big on atmosphere, though slightly cramped, and entry is free.

A splendid late-nineteenth-century structure comprises the ultimate venue for Dutch folk artists, and hosts all kinds of top international acts – anything from Van Morrison to Carmen, with reputable touring orchestras and opera companies squeezed in between.

Relaxed dance club, divided over three floors offering all styles of house and club music. Mixed audience with mainly students on Thursday and the hip and creative on weekends.

This vast club has space enough to house 2000 people, but its glory days – when it was home to Amsterdam’s cutting edge Chemistry nights – are long gone and it now focuses on weekly club nights that pull in crowds of mainstream punters. The opening of the Escape café, lounge and studio should pull in more trendsetting crowds though.

A classic gay club ideally situated for the fallout from the surrounding nightlife, with four bars playing different music from R&B to house. Attracts an upbeat, cruisey crowd. Predominantly male, though women are admitted. Don’t be surprised if you’re turned away if you haven’t dressed up.

Intimate and stylish club spread over two floors. Upstairs, the black lacquered walls, Japanese lamps and cosy booths with leather couches ooze sexy chic, while downstairs a packed dance floor throbs under hundreds of oscillating lightbulbs studded into the ceiling. Popular with young, well-dressed locals so look smart if you want to join in.

Probably Amsterdam’s most famous entertainment venue. A former dairy (hence the name) just round the corner from Leidseplein, this has two separate halls for live music, and puts on a broad range of bands covering everything from reggae to rock, all of which lean towards the “alternative”. Excellent DJ sessions go on late at the weekend. There’s also a monthly film programme, a theatre, gallery and café-restaurant (Marnixstraat entrance Wed–Sun noon–9pm).

Singel 460

![]() 020/850 2420

020/850 2420

Club Fri & Sat 11pm–5am; restaurant Fri & Sat from 6pm

Originally a brewery, this restored old canal house has since been a theatre, cinema and concert hall until it was gutted in a fire in 1990. Rescued, it’s now a stylish nightclub and restaurant.

A converted church near the Leidseplein, revered by many for its excellent programme, featuring local and international bands. Club nights such as Noodlanding! draw in the crowds, and look out too for DJ sets on Saturdays. It sometimes hosts classical concerts, as well as debates and multimedia events.

Right on the Rembrandtplein, this place celebrates the underground scene with techno, soul, funk, minimal and electro. A breeding ground for upcoming DJs and bands.

Busy Leidseplein’s latest addition is the “theatrical nightclub”, which hosts a programme of cabaret, live music, poetry and theatre, plus a late-night club that kicks off after the show. Pulls in a young and artistic crowd.