5 METADATA

To answer those questions you need good metadata.

—Geoff Nunberg

This chapter offers a first example of how the macroanalytic approach brings new knowledge to our understanding of literary history. This chapter also begins the larger exploration of influence that forms a unifying thread in this book. The evidence presented here is primarily quantitative; it was gathered from a large literary bibliography using ad hoc computational tools. To an extent, this chapter is about harvesting some of the lowest hanging fruit of literary history. Many decades before mass-digitization efforts, libraries were digitizing an important component of their collections in the form of online, electronic catalogs. These searchable bibliographies contain a wealth of information in the form of metadata. Consider, for example, Library of Congress call numbers and the Library of Congress subject headings, which they represent. Call numbers are a type of metadata that indicate something special about a book. Literary researchers understand that the “P” series is especially relevant to their work and that works classed as PR or PS have relevance at an even finer level of granularity—that is, English language and literature. This is an abundant, if somewhat general, form of literary data that can be processed and mined. Subject headings are an even richer source. Headings are added by human coders who take the time to check the text they are cataloging in order to determine, for example, whether it is fiction or nonfiction, whether it is folk literature or from the English Renaissance, and in the case of American literature whether it is a regional text from the northern, southern, central, or western region.

This type of catalog metadata has been largely untapped as a means of exploring literary history. Even literary bibliographers have tended to focus more on developing comprehensive bibliographies than on how the data contained within them might be leveraged to bring new knowledge to our understanding of the literary record. In the absence of full text, this bibliographic metadata can reveal useful information about literary trends. In 2003 Franco Moretti and I began a series of investigations involving two bibliographic data sets. Moretti's data set was a bibliography of nineteenth-century novels: titles, authors, and publication dates, not rich metadata, but a lot of records, around 7,000 citations. Moretti's work eventually led to a study of nineteenth-century novel titles published in Critical Inquiry (2009). My data set was a much smaller collection of about 800 works by Irish American authors.* The Irish American bibliography, however, was carefully curated and manually enriched with metadata indicating the geographic settings of the works, as well as the author gender, birthplace, age, and place of residence. Geospatial coordinates—longitudes and latitudes—indicating where each author was from and where each text was set were also added to the records.

The Irish American database began as research in support of my dissertation, which explored Irish American literature in the western United States (Jockers 1997). In 2001 the original bibliography of primary materials was transformed into a searchable relational database, which allowed for quick and easy querying and sorting. The selection criteria for a work's inclusion in the database were borrowed, with some minor variation, from those that Charles Fanning had established in his seminal history of Irish American literature, The Irish Voice in America: 250 Years of Irish-American Fiction (2000). To qualify for inclusion in the database, a writer must have some verifiable Irish ethnic ancestry, and the writer's work must address or engage the matter of being Irish in America. Because of this second criterion, certain obviously Irish authors, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and John O'Hara, are not represented in the collection. Both of these writers, as Fanning and others have explained, generally wanted to distance themselves from their Irish roots, so they avoided writing along ethnic lines. Thus, the database ultimately focused not simply on writers of Irish roots, but on writers of Irish roots who specifically chose to explore Irish identity in their prose.

Determining how and whether a work got included in the database was sometimes a subjective process. Some of the decisions made could, and perhaps should, be challenged. A perfect example is the classification of Kathleen Norris as a Californian. Norris was raised and began her writing career in and among the Irish community of San Francisco. After marrying, though, she moved to New York, where she continued to write, sometimes setting her fiction in California and sometimes in New York. In the database, she is consistently classed as a Californian and not a New Yorker. Norris strongly identified with her San Francisco Irish American heritage, stating in her autobiography that she was part of the San Francisco “Irishocracy” (1959). Even though she lived and wrote for a time on the East Coast, she never lost her California Irish identity. She ultimately returned to California and died at her home in Palo Alto.

Constructed over the course of ten years, this database includes bibliographic records for 758 works of Irish American prose literature spanning 250 years.* Given the great time span, this is not a huge corpus. Nevertheless, it is a corpus that approaches being comprehensive in terms of its selection criteria. Each record in the database includes a full bibliographic citation, a short abstract, and additional metadata indicating the setting of the book: geographic coordinates and information such as state or region, as well as more subjectively derived information such as whether the setting of the text is primarily urban or rural. The records also include information about the books’ authors: their genders and in many cases short biographical excerpts.†

In the absence of this data, our understanding of Irish American literature as a unique ethnic subgenre of American literature has been dependent upon critical studies of individual authors in the canon and upon Fanning's study of the subject.‡ In The Irish Voice in America, Fanning explores the history and evolution of the canon using a “generational” approach. He begins with the watershed moment in Irish history, the Irish Famine of the 1840s, and then explores the generations of writers who came before, during, and after the famine. When he reaches the turn of the twentieth century, Fanning moves to an examination of the literature in the context of key events in American and world history: the world wars and then the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Fanning's is a far-reaching study that manages to provide astonishing insight into the works of several dozen individual authors while at the same time providing readers with a broad perspective of the canon's 250-year evolution. It is a remarkable work. A rough count of primary works in Fanning's bibliography comes in at nearly 300.*

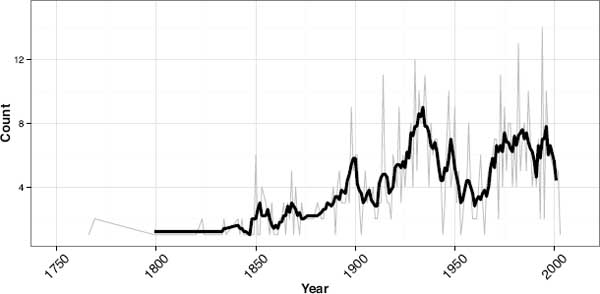

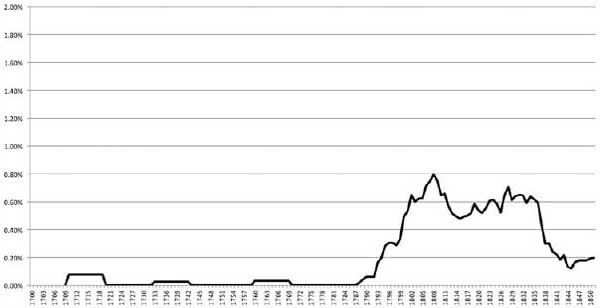

In the course of his research, Fanning discovered an apparent dearth of writers active in the period from 1900 to 1930, and as an explanation for this literary “recession,” Fanning proposes that 1900 to 1930 represents a “lost generation,” a period he defines as one “of wholesale cultural amnesia” (2000, 3). Fanning hypothesizes that a variety of social forces led Irish Americans away from writing about the Irish experience, and he notes how “with the approach of World War I, Irish-American ethnic assertiveness became positively unsavory in the eyes of many non-Irish Americans. When the war began in August of 1914, anti-British feeling surfaced again strongly in Irish-American nationalist circles…. [T]he War effort as England's ally, and the negative perception of Irish nationalism after the Easter Rising all contributed to a significant dampening of the fires of Irish-American ethnic self-assertion during these years” (ibid., 238). The numbers, however, tell a different story. Figure 5.1 shows a chronological plotting of 758 works of Irish American fiction published between the years 1800 and 2005.† The solid black line presents the data as a five-year moving average; the noisier dotted line shows the actual, year-to-year, publications. This graph shows nothing more elaborate than the publication history. Noteworthy, however, is that the literary depression, or lost generation, that Fanning hypothesizes appears to be much more short-lived than he imagines. A first peak in Irish American publication occurs just at the turn of the twentieth century. This is followed by a short period of decline until 1910. Then, however, the trend shifts upward, and the number of publications increases in the latter half of the exact period that Fanning identifies as one when Irish Americans were supposed to have been silenced by cultural and social forces. Where is the lost generation that Fanning postulates?

Figure 5.1. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction

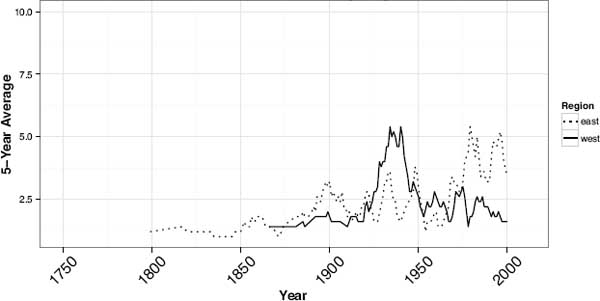

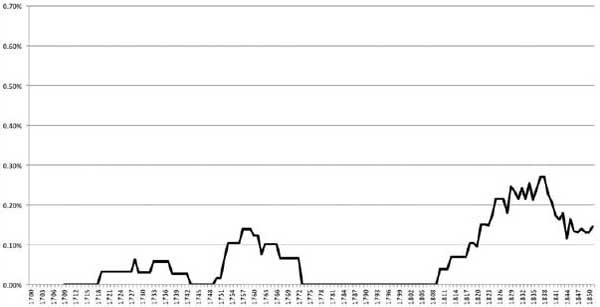

When the results are regraphed, as shown in figure 5.2, so as to differentiate between Irish American authors from east and west of the Mississippi, we begin to see how Fanning may have been led to his conclusion: publication of works by eastern Irish American writers does indeed begin to decline in 1900, reaching a nadir in 1920. Eastern writing does not begin to recover from this “recession” until the decade of the 1930s, and full recovery is not achieved until the late 1960s and early 1970s.

If we look only to the dotted (eastern) line, then Figure 5.2 confirms Fanning's further observation that Irish American fiction flourished at the turn of the century and then again in the 1960s and ‘70s, when cultural changes made writing along ethnic lines more popular and appealing. The western line, however, tells a different story. Western writers make a somewhat sudden appearance in 1900 and then begin a forty-year period of ascendancy that reaches an apex in 1941. Western writers clearly dominated the early part of the twentieth century.

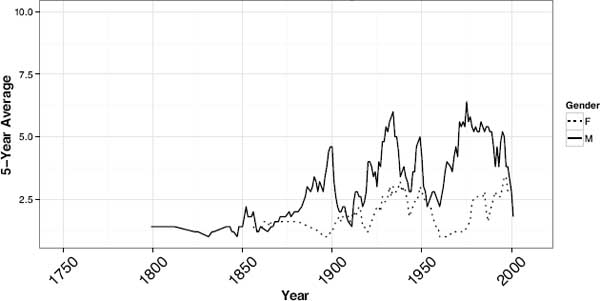

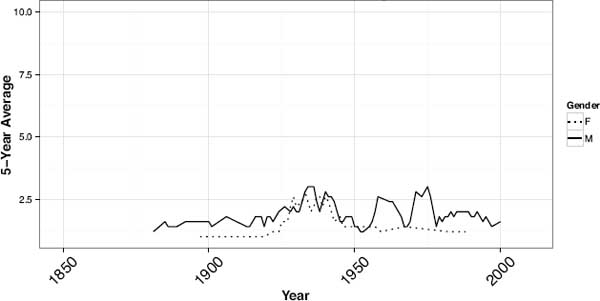

A further separation of texts based on author gender reveals even more about what was happening in this period. To begin, Figure 5.3 shows all texts separated by gender. With the exception of the 1850s, male productivity is consistently greater than female productivity. Aside from this somewhat curious situation in the 1850s, the male and female lines tend to follow a similar course, suggesting that the general trends in Irish American literary production are driven by forces external to gender.*

Figure 5.2. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction by region

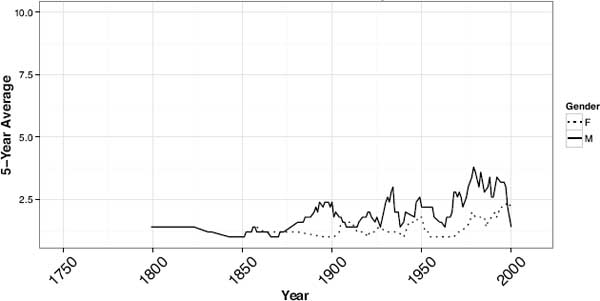

Figure 5.4, however, presents a view of only eastern Irish American texts separated by gender. Here, in the East, publications by male authors are seen to suffer a much more precipitous drop after the turn of the century, declining from an average of 2.3 publications per year to 1.3 by 1916. Females are seen to have a slight increase in productivity around 1906, a surge lasting for about ten years.

More striking than this graph of eastern publications, however, is figure 5.5, which charts western publications separated according to gender. Whereas western male authors are increasing their production of texts beginning in the 1860s to an apex in the late 1930s, Irish American women in the West first appear in the late 1890s and then rise rapidly in the 1920s to a point at which they are producing an equal number of books per year to their male counterparts in the West. Given the overall tendency for women to produce at a rate lower than males, this is especially noteworthy. It suggests either that the West offered something special for Irish American women or that there was something special about the Irish women who went west, or, still more likely, that it was some combination of both.*

Figure 5.3. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction by gender

Figure 5.4. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction by gender and eastern region

Figure 5.5. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction by gender and western region

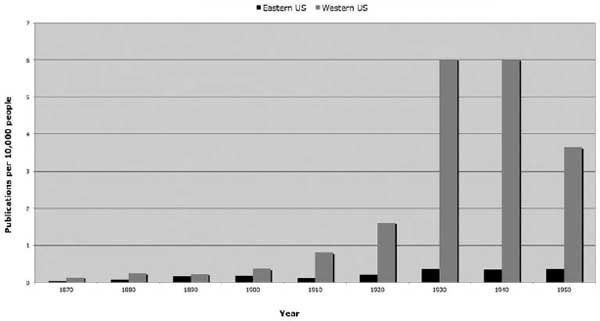

Western authors, both male and female, certainly appear to have countered any literary recession of the East. That they succeeded in doing so despite (or perhaps directly because of) a significantly smaller Irish ethnic population in the West is fascinating. Figure 5.6 incorporates census figures to explore Irish American literary output in the context of eastern and western demographics. The chart plots Irish American books published per ten thousand Irish-born immigrants in the region. A natural assumption here is that there should be a positive correlation between the size of a population and the number of potential writers within it. What the data reveal, however, is quite the opposite: the more sparsely populated West produced more books per capita.

In addition to further dramatizing the problems with Fanning's argument about Irish American authors being stifled in the early part of the twentieth century, these data reveal a counterintuitive trend in literary productivity. Geographically removed from the heart of the publishing industry in the East, Irish Americans in the West were also further removed from the primary hubs of Irish culture in cities such as Boston, New York, and Chicago. Given a lack of access to the steady influences of the home culture, we might expect Irish immigrants in the West to more quickly adopt the practices and tendencies of the host culture. One might even imagine that in the absence of a supportive Irish American culture, American writers of Irish extraction would tend to drift away from ethnic identifications and write less ethnically oriented fictions. Quite to the contrary, though, Irish Americans in the West wrote about being Irish in America at a per capita rate exponentially greater than their countrymen in the East.

Figure 5.6. Irish American fiction per capita

The bar graph in figure 5.6 shows book publications per ten thousand Irish immigrants. The gray bar shows productivity of western authors and the black bar that of eastern. In the 1930s, as an example, western writers were producing 6 works for every ten thousand Irish immigrants. East of the Mississippi, in the same year, Irish American authors managed just 0.3 books per ten thousand, or 1 book for every thirty thousand Irish immigrants.* Even in the years outside of the period, from 1900 to 1940, Irish American authors in the West consistently outpublished their eastern counterparts in terms of books per Irish immigrants.* Although it is true that 758 texts spread over 250 years does not amount to very many data, the aggregation of the data into decades and the visualization of the data in terms of ten-year moving averages do provide a useful way of considering what are in essence “latent” macro trends. Given the sparsity of the data, this analysis is inconclusive if still suggestive.† It suggests that geography, or some manifestation of culture correlated to geography, exerted an influence on Irish American literary productivity.

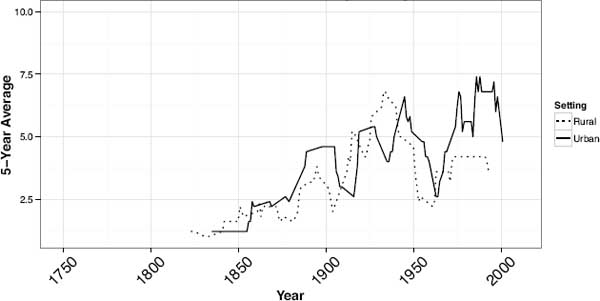

A similar avenue of investigation can be traveled by studying the distribution of texts based on their fictional settings. In addition to metadata pertinent to author gender, state of residence, and geographic region, works in this database are coded with information about their fictional settings. Each record is marked as being either “rural,” “urban,” or “mixed.” Graphing only those works that fall clearly into the category of being either rural or urban provides additional information for understanding the distribution and makeup of Irish American literature. Figure 5.7 shows the publication of fictional works with either rural or urban settings that were published between 1760 and 2010. Looking specifically at the period from 1900 to 1940, a trend toward the dominance of urban works begins in 1930s and peaks around 1940. What is not revealed here is that western authors were in fact writing the majority of the works with urban settings. From 1900 to 1930, it was western Irish Americans who put urban America on the map, and this leads us to further interrogate Fanning's observations of a lost generation. It appears that this lost generation is in fact a lost generation of eastern, and probably male, Irish Americans with a penchant for writing about urban themes.

Figure 5.7. Chronological plotting of Irish American fiction by setting

It is hard not to draw this conclusion, especially when we consider that the history of the Irish in America, and to a much greater extent the history of Irish American literature, has had a decidedly eastern bias. Just how prevalent this eastern bias is can be read in the preface to Casey and Rhodes's 1979 collection, Irish-American Fiction: Essays in Criticism. William V. Shannon writes in the preface that the essay collection examines the “whole ground of American-Irish writing [and] demonstrates the scope and variety of the Irish community's experience in the United States” (ix). Although Shannon's enthusiasm is in keeping with the significance of this seminal collection, his remarks about its breadth are incredibly misleading. An examination of the essays in the collection reveals not a comprehensive study but rather a study of Irish American authors centered almost exclusively in eastern, urban locations. Writers from the Great Plains and farther west are absent, and thus the collection misses the “whole ground” of the Irish American literary experience by about 1,806,692 square miles.*

Such neglect is surprising given the critical attention that the Irish in the West have received from American and Irish historians. Although it is true that a majority of historical studies have tended to focus on Irish communities in eastern, urban locations such as Boston and New York, since the 1970s, at least, there has been a serious effort made to chronicle the Irish experience beyond the Mississippi. By 1977 Patrick Blessing had pointed out that the current view of Irish America had “been painted rather gloomily” by historians focusing too much on cities like Boston (2). At that time, he noted that “studies of the Irish in the United States [had] been confined to the urban industrial centers on the East coast” (ibid.). Scholarly opinion of the Irish in America was also still very eastern centric and largely fixated on the struggles faced by famine-era immigrants. Blessing's study of Irish migration to California, however, forced reconsideration of the existing views. The census figures that Blessing cites from the late nineteenth century reveal what few had been willing to recognize: not only were there large numbers of Irish in the West, but in many cases they were the dominant ethnic group. From 1850 to 1880, for example, the Irish were the largest immigrant group in Minnesota, Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, Montana, Arizona, Nevada, and Washington, and they were the second largest in Utah, Idaho, Oregon, and the Dakota Territory (ibid., 169). Using these figures along with other qualitative evidence, Blessing argued that the long-held opinion that “Irish immigrants were reluctant to move out of the urban Northeast” needed serious reconsideration (ibid., 162). More important, he dispelled the idea that the Irish were “strongly averse to going West” by pointing to figures showing how by 1850, “200,000 Irish labored in regions outside of the eastern states.” By 1880 the number had risen to “almost 700,000, fully 36 percent of the entire group in the United States” (ibid., 163). Of this eastern bias, Blessing writes, “That historians should attend to the Irish clustered in Eastern cities is understandable, for the majority could be found in or around their port of arrival for decades after debarkation in the United States…. To emphasize Irish reluctance to depart the urban Northeast, however, is to neglect the considerable proportion of newcomers from the Emerald Isle who did leave the region” (ibid.).

If neglecting the West is one problem, another is most certainly the neglect of Irish American women. Writing of this neglect, Caledonia Kearns notes that the “history of Irish American women in this country has been little recognized, with the exception of Hasia Diner's groundbreaking book Erin's Daughters in America” (1997, xvii). When it comes to studies of Irish American literature by women, the record is even worse. Kearns goes on to point out that there are, to begin with, very “few studies of Irish-American fiction…and when [Irish American fiction is] considered, the focus tends to be on male writers” (ibid., xviii). Assuming that scholars, the reading public, and book reviewers have been guilty of exactly what Blessing and Kearns suggest, it is instructive to consider what is available to counter these biases within the Irish American literary canon. A reader, reviewer, or scholar with this sort of male, urban, and eastern bias finds very little in the Irish American corpus between 1900 and 1940. Indeed, only 5 percent of the texts published in that forty-year period meet the criteria of being male, eastern, and urban. When the biases are completely reversed (female, western, and rural), we find almost twice as many books. In retrospect it is clear that even Fanning's sweeping study of Irish American literature is fundamentally canonical and anecdotal. Nevertheless, he cannot be faulted on this point, as he had neither the data nor the methodology for doing otherwise. There is only so much material that can be accounted for using traditional methods of close reading and scholarly synthesis.*

The macroanalytic perspective applied here provides a useful, albeit incomplete, corrective. The approach identifies larger trends and provides critical insights into the periods of growth and decline in the corpus. The graphs and figures are generated from a corpus of 758 works of fiction, and although it is not unreasonable or even impossible to expect that an individual scholar might read and digest this many texts, it is a task that would take considerable time and would push the limits of the human capacity for synthesis. Moreover, it would be a nontrivial task for even the most competent of traditional scholars to assemble the varied impressions resulting from a close reading of more than 750 texts into a coherent and manageable literary history. Not impossible, for sure, but surely impractical on many counts. Cherry-picking of evidence in support of a broad hypothesis seems inevitable in the close-reading scholarly tradition.

Given the impracticalities of reading everything, the tendency among traditional literary historians has been to draw conclusions about literary periods from a limited sample of texts. This practice of generalization from the specific can be particularly dangerous when the texts examined are not representative of the whole. It is worth repeating here what was cited earlier. Speaking of the nineteenth-century British novel, Moretti writes, “A minimal fraction of the literary field we all work on: a canon of two hundred novels, for instance, sounds very large for nineteenth-century Britain…but is still less than one per cent of the novels that were actually published…. [A] field this large cannot be understood by stitching together separate bits of knowledge about individual cases” (2005, 4). Comments such as these have moved some to charge that Moretti's enterprise runs counter to, and perhaps even threatens, the very study of literature. William Deresiewicz (2006) uses his review of Moretti's edited collection The Novel as a platform on which to cast Moretti as some sort of literary “conquistador.” He depicts Moretti as a warrior in a literary-critical “campaign.” Deresiewicz draws a line in the sand; he sets up an opposition and sees no room in literary criticism for both macro (distant) and micro (close) approaches to the study of literature. In his combat zone of criticism, scholars must choose one methodology or the other. But Deresiewicz is wrong. Moretti's intent is not to vanquish traditional literary scholarship by employing the howitzer of distant reading, and macroanalysis is not a competitor pitted against close reading. Both the theory and the methodology are aimed at the discovery and delivery of evidence. This evidence is different from what is derived through close reading, but it is evidence, important evidence. At times the new evidence will confirm what we have already gathered through anecdotal study (such as Fanning's observation of the flourishing of Irish American fiction in the 1960 and 1970s). At other times, the evidence will alter our sense of what we thought we knew. Either way the result is a more accurate picture of our subject. This is not the stuff of radical campaigns or individual efforts to “conquer” and lay waste to traditional modes of scholarship.

• • •

Simple counting and sorting of texts based on metadata inform the analysis of Irish American fiction provided above but by no means provide material for an exhaustive study. Any number of measures might be brought to bear on an attempt to better understand a literary period or canon. We might be interested in looking at sheer literary output, or we might be interested in output as it relates to population. A “books per capita” analysis, such as that seen in figure 5.6, may prove useful in assessing the validity of claims that are frequently made for literary “renaissances.” Was the flowering of black American drama during the 1930s and 1940s attributable to the creative genius of a few key writers, or was the production of so much writing simply a probability given the number of potential writers?

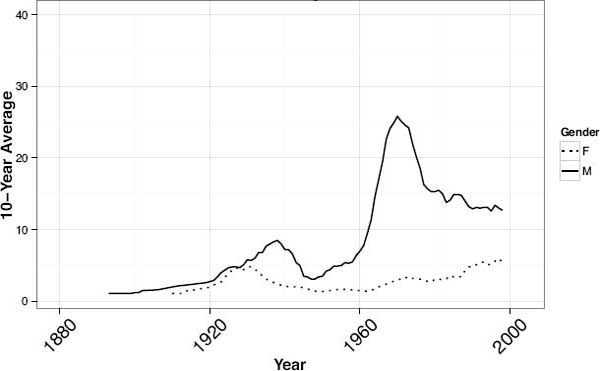

In order to assess this question reliably, it would be appropriate to explore first the sheer number of plays produced per year. We might then calculate the average number of plays per decade, or in some other time span. It might also be appropriate to compare the production of black drama against or within the context of the larger canon of American drama in general. Was the output of black dramatists in these years significantly greater than their Caucasian counterparts? Was there a similar burgeoning of drama outside of the African American community during this time period? Obviously, the answers to these questions could have a profound influence on the way that we understand American drama in general and African American literature in particular. Answering these questions is dependent not just upon the availability of the plays themselves but also upon the added information that is provided in the form of metadata about the plays. For readers eager to investigate this question, such metadata (and much more) are part of the wonderfully conceived Alexander Street Press collection Black Drama. The current (second) edition of the collection includes 1,450 plays written from the mid-1800s to the present by more than 250 playwrights from North America, English-speaking Africa, the Caribbean, and other African diaspora countries.* Figure 5.8, showing a chronological plotting of plays in the Black Drama collection separated by gender, probably tells us more about the collection practices of the Alexander Street Press editors than it does about black dramatic history.

Figure 5.8. Chronological plotting of black drama by gender

Whatever the case, the chart is revealing all the same. It may suggest, for example, that black males are far more likely dramatists, or maybe there was something special about the 1970s that led male authors and not female authors to write drama. It may also reveal that the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ‘30s was a period when female dramatists were either more active or more appreciated by posterity. Needless to say, these are the kind of questions that should be taken up by those with domain expertise in African American literature. Collections such as this one from Alexander Street Press are fertile ground for even deeper macroanalytic research because the collection has both rich metadata and full text.

We have seen what appears to be a strong connection between geography and Irish American productivity. In addition to informing our understanding of raw productivity, metadata such as those contained in the Irish American database can also provide some limited insight into the content and style of novels. In the United States, it is common to explore literature in terms of region, to separate, distinguish, and categorize genres based on geographical distinctions: the New England poets, the southern regionalists, western American fiction, and so on. The Irish American database is limited; it is ultimately no more than an enhanced bibliography. Given a full-text database with similarly rich metadata, however, we can construct queries that allow for exploration of how literary style and the choices that authors make in linguistic expression vary across disparate regions. Much in the way that linguists study dialects or “registers” in the context of geography, a study of “literary” style in connection with geographic context has the potential to reveal that western writers are given to certain habits of style that do not find similar expression in the East. Where linguists are interested in the general evolution of language, scholars of literary style are interested in the ways in which a writer's technique, or method of delivery, is unique. Do the southern regionalists have a distinct literary style or dialect that marks them as different from their northern counterparts? Is the “pace” of prose by southern writers slower? Are southern writers more prone to metaphorical expression? Do northerners use a larger working lexicon? Obviously, we would expect certain lexical differences between southern and northern writers—by definition these works are influenced by geography; regional writers inevitably reference local places and customs. An intriguing question, though, is whether there exists a detectable stylistic difference beyond these toponyms or regional distinctions. An even thornier question might investigate the extent to which novelistic genre determines novelistic style or the degree to which literature operates as a system composed of predictable stylistic expressions. These are bigger questions reserved for the later chapters of this book. A less ambitious question is useful for further introducing the macroanalytic methodology: to what extent does geography influence content in Irish American literature? Without a full-text corpus, a slightly more focused question is necessary: are Irish American writers from the West more or less likely to identify their ethnic backgrounds than writers from the East? Not only is this a tractable question in its practicality, but it is also an important question, because a good number of Irish American authors, particularly some very prominent writers, including Fitzgerald and O'Hara, have intentionally avoided the use of ethic markers that would brand their work as “Irish.” Not until the election of John F. Kennedy did Irish Americans fully transcend (whether in actuality or just symbolically) the anti-Catholic and anti-Irish prejudice that typified the late 1800s, when poor Irish Catholic immigrants flooded American shores. Arguably, some of the same stigma and stereotyping remain today, but by and large the typecasting of Irish Americans is no longer of a particularly disparaging sort. Nevertheless, for those Irish Americans who wrote and wished to succeed as writers in the wake of the Great Famine, having an Irish surname was not necessarily a marketable asset. Unless a writer was willing to play up all the usual stereotypes of the so-called stage Irishman, that writer would do best to avoid Irish themes and characters altogether. If we accept this premise, then those who do engage ethnic elements in their fiction are worthy of study as a distinct subset of American authors.

Claude Duchet has written that the titles of novels are “a coded message—in a market situation” (quoted in Moretti 2009, 134). In fact, the titles of novels are an incredibly useful and important, if undertheorized, aspect of the literary record. As Moretti has demonstrated, in the absence of a full-text archive, the titles of works may serve as a useful, if imperfect, proxy for the novels themselves. In the case of Irish American fiction, where there is a historical or cultural background of intolerance for Irish themes, the titles of works carry a special weight, for it is in the title that an author first meets his readers. To what extent, then, do Irish American authors identify themselves as Irish in the titles of their books? By comparing the frequency and distribution of specific word types—ethnic and religious markers in this case—over time and by region, the analysis of publication history presented above can be further demystified.* The use of ethnic and religious markers in the titles of works of Irish American literature first surges in the decades between 1850 and 1870: ethnic or Catholic markers (or both) appear in 30 percent of the titles in the 1850s, 33 percent in the 1860s, and 43 percent in the 1870s. These are the years just after the Great Famine in Ireland. Many of the authors employing these terms are immigrants: first-generation Irish Americans writing about what they know best—their homeland and their people. These are mostly educated authors who may have, as a result of their class or wealth, avoided direct discrimination upon arrival in America. In the decade of the 1880s, however, we find exactly zero occurrences of ethnic markers in titles of Irish American texts, and from 1890 through 2000, the usage of marker words reaches only 11 percent in the 1890s and then never exceeds 6 percent. This naturally raises a question: what happens in or around 1880 to cause the precipitous decrease? Here we must move from our newly found facts to interpretation.

The most obvious answer is postimmigration discrimination. By 1880 the greatest movement of immigrants escaping the famine had occurred, and by 1880 there is likely to have been enough anti-Irish, anti-Catholic sentiment in the United States to make identifying one's Irishness a rather uncomfortable and unprofitable idea.* A closer inspection of these data, however, reveals that after 1880, the use of these markers decreases only in the titles of books written by and about Irish people east of the Mississippi. Irish writers west of the Mississippi continue to employ these “markers” in the titles of their fictional works, especially so in the decade between 1890 and 1900, when every single text employing one of these ethnic identifiers, and accounting for 11 percent of all the Irish American texts published that decade, comes from a writer who lived west of the Mississippi.

Writers employing ethnic markers are also predominantly writers of rural fiction. After 1900 all but a few instances of these markers occur in titles of works that take place in rural settings, as in Charles Driscoll's book Kansas Irish, for example.† As we see in table 5.1, in the decade from 1900 to 1909, 7 percent of rural works included an obviously ethnic identifier, 22 percent in the decade from 1910 to 1919. Urban texts using ethnic identifiers during the same decades appeared only in 1940–49 at 7 percent, 1970–79 at 4 percent, and 1980–89 at 2 percent. The pattern here is fairly straightforward: western writers and writers of rural fiction are more likely to depict Irishness and more likely to declare that interest to would-be readers in the titles of their books.‡ Western Irish American writers are evidently more comfortable, or at least more interested in, declaring the Irishness of their subject.

In obvious ways, titles serve as advertisements or marketing tools for the book as a whole, but they frequently also serve to convey authors’ condensed impressions of their works. Consider, for example, the following two titles: The Irish Emigrant: An Historical Tale Founded on Fact and The Aliens. Both of these texts deal with Irish immigration to the United States. The first, a book published in 1817, clearly identifies the subject of Irish immigration. The later book, from 1886, deals with the same subject, but provides nothing to identify itself in ethnic terms. Might it be the case that the author of the former text felt comfortable (prior to the famine and prior to the significant anti-Irish prejudice that permeated American society in the postfamine years) identifying the Irishness of his subject? Pure conjecture, to be sure, but such a hypothesis makes intuitive sense.

Table 5.1. Percentage of rural and urban texts using ethnic markers

| Decade | Rural texts (%) | Urban texts (%) |

| 1900–1909 | 7 | 0 |

| 1910–19 | 22 | 0 |

| 1920–29 | 0 | 0 |

| 1930–39 | 4 | 0 |

| 1940–49 | 0 | 7 |

| 1950–59 | 0 | 0 |

| 1960–69 | 0 | 0 |

| 1970–79 | 18 | 4 |

| 1980–89 | 29 | 2 |

| 1990–99 | 0 | 0 |

| 2000–2005 | 9 | 0 |

To scholars of Irish American literature and culture, the geographic and chronological analysis explored here confirms an important suspicion about the role that culture and geography play in determining not only a writer's proclivity to write but also the content and sentiment that the writing contains. Historians including James Walsh (1978), David Emmons (1989, 2010), Patrick Blessing (1977), and Patrick Dowling (1988, 1998) have documented how Irish immigrants to the American West faced a different set of challenges from that of their countrymen who settled in the East. The foremost challenges that these western immigrants endured were natural challenges associated with frontier living. With minor variations, these historians all attribute the comparative success of the Irish in the West to the fact that these Irish did not face the same kinds of religious and ethnic intolerance that was common fare among the established Anglo-Protestant enclaves of the East. Quite the opposite, the Irish who ventured west to the states of New Mexico, Texas, and California found in the existing Catholic population a community that welcomed rather than rejected them. Those who went to Colorado and Montana found plentiful jobs in the mines and an environment in which a man was judged primarily upon the amount of rock he could put in the box.* These conditions laid the groundwork not simply for greater material success but, as these data confirm, greater literary productivity and a body of literature that is characterized by a willingness to record specifically Irish perspectives and to do so with an atypical degree of optimism.*

A still closer analysis of all these data is warranted, but even this preliminary investigation reveals a regular and predictable pattern to the way that Irish American authors title their works. This pattern corresponds to the authors’ chronological and geographic position in the overall history of Irish immigration to the United States. This type of analysis is ripe for comparative approaches; an exploration of titles produced by other ethnic immigrants to the United States would provide fruitful context. Might a similar pattern be found in Jewish American fiction? Surely, there are a number of similarities between the two groups in terms of their fiction and their experiences as immigrants to the United States. An interested researcher need only identify and code the bibliographic data for the Jewish American tradition to make such an analysis possible.

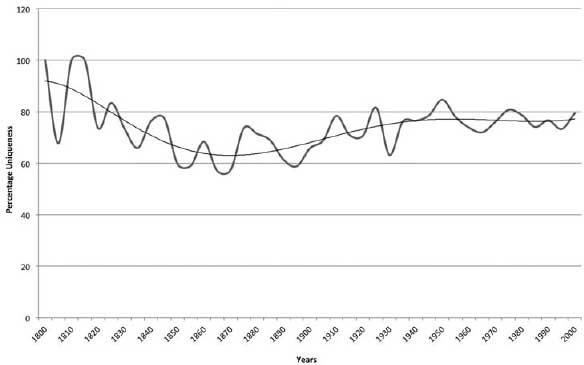

In addition to various forms of comparative analysis that might be made by compiling and comparing parallel bibliographies, it is possible to take these data still further, to go beyond the mere counting of title words, and to analyze the actual use of words within those titles. Figure 5.9, for example, provides a graphical representation of lexical richness, one of several ways of measuring linguistic variety. Lexical richness, also called a Type Token Ratio, or TTR, is a measure of the ratio of unique words to total word tokens in a given text. Lexical richness may be used to compare the lexicon of two authors. Herman Melville's Moby Dick, for example, has a TTR of 7.8 and draws on a large vocabulary of 16,872 unique word types. Jane Austen's Sense and Sensibility has a TTR of 5.2 and a much smaller vocabulary of 6,325 unique word types. Austen uses each word type an average of nineteen times, whereas Melville uses each word an average of thirteen times. The experience of reading Moby Dick, therefore, appears to be one in which a reader encounters many more unique words and fewer repeated words, on average. However, into this equation, we must also consider novel length. Although Melville's working vocabulary in Moby Dick is considerably larger than Austen's in Sense and Sensibility, Melville's novel, at 214,889 total words, is almost double the length of Austen's novel, at 120,766. We can compensate for this difference in length by taking multiple random samples of 10,000 words from both novels, calculating the lexical richness for each sample, and then averaging the results. In the case of Austen, 100 random samples of 10,000 words returned an average lexical richness of 0.19. A similar test for Melville returned an average of 0.29. In other words, in any given sample of 10,000 words from Moby Dick, there are an average of 2,903 unique word types, whereas a similar sample from Austen returns an average of just 1,935. In terms of vocabulary, Melville's Moby Dick is a far richer work than Sense and Sensibility.

Figure 5.9. Chronological plotting of lexical richness in Irish American fiction titles

Applying a lexical-richness measure to the titles of works, it is possible to examine the degree to which the “title lexicon” of a given period is or is not homogeneous. Using title data, we can approximate the lexical variety of titles in the marketplace at any given time. Figure 5.9 charts lexical richness in Irish American titles over time and makes immediately obvious a movement toward lexical equilibrium. The smoother line in the graph shows the overall trend (that is, the mean) in lexical richness of titles; the other, wavier, line allows us to visualize the movement toward less variation. Deviation from the mean decreases over time. The fluctuations, the deviations from the mean, become smaller and smaller and reach a steadier state in the 1930s.* In the early years of the corpus, there is greater heterogeneity among the titles; that is, there is a higher percentage of unique words than in later periods. In practical terms, what this means is that a potential reader browsing titles in the 1820s would have found them very diverse (in terms of their vocabularies—and, by extension, their presumed subjects), whereas a reader of more recently published texts would find greater similarity among the titles available on this hypothetical bookshelf. More interesting than the general movement toward equilibrium, at least for readers interested in Irish American literature, is the “richness recession” that bottoms out in a period roughly concomitant to the Great Famine. Fanning, who has read more of this literature than any other scholar, has characterized this period of Irish American fiction as one that is generally lacking imagination. The low lexical richness of titles from this period serves as a useful quantitative complement to his qualitative observation. Still, given the relatively small size of this corpus, hard conclusions remain difficult to substantiate statistically.

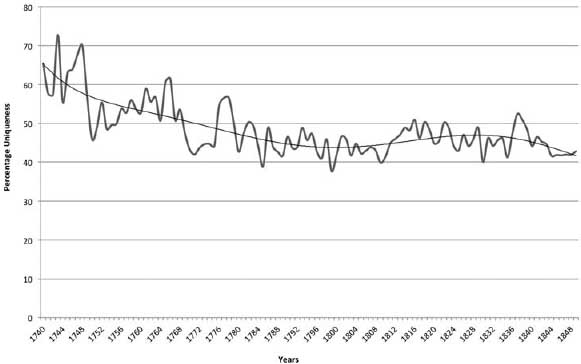

With a larger collection, such as Moretti's bibliography of British novels published from 1740 to 1850, a measure of lexical richness over time can be much more informative. Moretti's bibliography includes 7,304 titles spanning 110 years, an average of 66 titles per year. Figure 5.10 provides a graphical representation of the lexical richness of these titles over time. In the year 1800, to pick a somewhat arbitrary example, there are 81 novels. Only one of these novel titles contains the word Rackrent: Maria Edgeworth's Castle Rackrent. Castles, on the other hand, were quite popular in 1800. The word castle appears in 10 percent of the 81 titles for 1800. After filtering out the most common function words (the, of, on, a, in, or, and, to, at, an, from) and the genre markers (novel, tale, romance), castle is, in fact, the most frequently occurring word. This is not entirely surprising, given the prominence of the Gothic genre between 1790 and 1830 and the fact that the prototype novel of the genre, Walpole's Castle of Otranto, establishes the locale and sets the stage for many years of imitation.

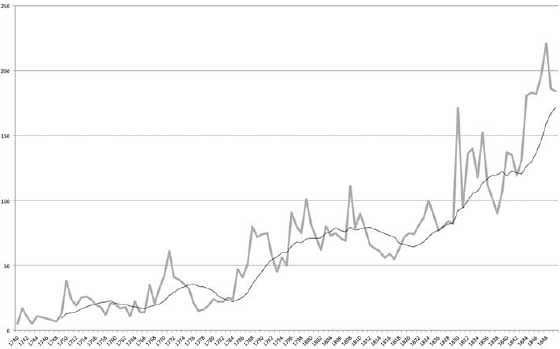

Figure 5.10 charts the year-to-year Type Token Ratio. In 1800 there were 275 word types and 659 total tokens, a richness of 42 percent. Titles in that year averaged 8 words in length and contained an average of 3.4 unique words each. The richness figure provides one measure of the relative homogeneity of titles available to readers of British novels in 1800. Looking at the bigger picture, we see that as time progresses, from 1740 to 1840, titles are becoming less unique, and the working vocabulary of title words is shrinking, and all this is happening at a time when the overall number of titles published is increasing dramatically. Figure 5.11 plots the number of titles in the corpus in every year, dramatizing the extent to which the corpus expands over time.

Put another way, the lexicon of words that authors are using to title their works is becoming more homogeneous even while the number of books and the number of authors in the marketplace are increasing. If we accept, with Duchet and Moretti, that titles are an important signal or code in a crowded market, then this is a sobering trend, at least for authors wishing to stand out at the bookseller's. Instead of titles that distinguish one book from another, what is found is a homogenization in which more and more book titles look more and more the same. Moretti has commented on a similar trend in the length of the titles, but not on the specific vocabulary that is deployed.*

Figure 5.10. Chronological plotting of lexical richness in British novel titles

Figure 5.11. The number of British novel titles per year

The word romance, for example, is a popular word in this corpus of titles. After removing function words, it is, in fact, the sixteenth most frequently occurring title word overall. It is also a word that goes through a distinct period of popularity, peaking around 1810 and then going out of fashion for thirty years before resurfacing in the 1840s (see figure 5.12). There are any number of explanations for the trend seen here, but my purpose is not to explain the uptick in romance, but to instead show the larger context in which titles bearing the word romance appear, or, put more crassly, to show what the competition looks like. A writer using the word romance in the 1810s is far less original than those writers employing the term in the mid- to late 1700s. Those early, smaller, “blips” in the romance timeline, seen around the 1740s and 1760s, are early adopters, outliers to the main trend; they are pioneers in the usage of the term, and anyone wishing to understand the massive use of romance at the turn of the century should most certainly contextualize that analysis by a closer look at the forerunners to the trend.

In comparison, the word love is a relative nonstarter, a title word that maintains a fairly steady usage across the corpus (figure 5.13) and never experiences the sort of heyday that is witnessed with romance.

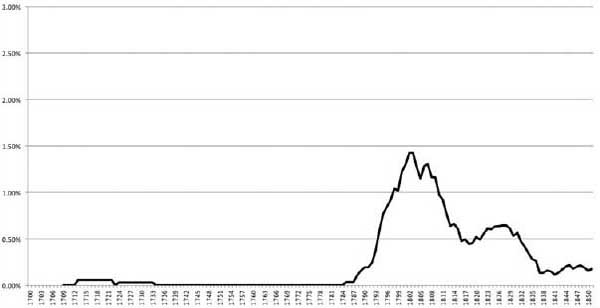

Castle (figure 5.14), on the other hand, behaves much more like romance, whereas London (figure 5.15) is similar to love. The behavior of the word century (figure 5.16) is unsurprising—it begins a rise toward prominence just before the turn of the century, peaks just after the turn, around 1808, and then hangs on until about 1840, when it apparently became old news, passé, cliché. Scholars of the Irish will find food for thought in figure 5.17, which plots the frequency of the word Irish in this corpus of titles. It is never a particularly popular term, just sixty-second overall, but as we can see, it experiences a slight rise in the third quarter of the eighteenth century and then a stronger surge in the first quarter of the nineteenth. Most thought provoking, though, is the silence seen in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and first decade of the nineteenth. Talk about a lost generation! Why Ireland and the Irish were unpopular subjects for novel titles in this period is uncertain; that they utterly disappear from the library and bookstore shelves is clear.

• • •

Figure 5.12. chronological plotting of romance in British novel titles

Figure 5.13. Chronological plotting of love in British novel titles

Figure 5.14. Chronological plotting of castle in British novel titles

Figure 5.15. Chronological plotting of London in British novel titles

Figure 5.16. Chronological plotting of century in British novel titles

Figure 5.17. Chronological plotting of Irish in British novel titles

The data discussed in this chapter raise more questions than they answer. Such a fact should come as some relief to those who worry that the quantification of literature will ring the death knell for further study. At least one intriguing thread to arise from this explorative analysis, however, involves the matter of external influence and the extent to which factors such as gender, ethnicity, time, and geography play a role in determining the choices that authors make about what they write and how their works get titled. It does appear that gender, geography, and time are influential factors in novel production, novel titles, and even the subjects that authors decide to write about. But titles and rich metadata take us only so far. The next chapter investigates these questions by exploring linguistic style in the full text of 106 novels from twelve popular genres of nineteenth-century prose fiction.

* The results of Moretti's project were first delivered as the keynote address at the 2007 digital humanities conference in Champaign-Urbana and then published in Critical Inquiry (Moretti 2009). The results of my analysis of the Irish American data set were presented in two different formats: first in 2007 as an invited lecture titled “Metadata Mining the Irish-American Literary Corpus,” at the University of St. Louis, and then again at the 2007 meeting of the Modern Language Association in a paper titled “Beyond Boston: Georeferencing Irish-American Literature.”

* The database includes other types of works in addition to prose fiction, but my analysis excludes these works. I began collecting these data as part of my doctoral dissertation and continued expanding it through 2005. During that time, I was assisted by students enrolled in my Irish American literature courses at Stanford and by graduate students employed as part of a grant I received from the Stanford Humanities Lab to fund the “Irish-American West” project. In 2004 I cofounded the Western Institute of Irish Studies with then Irish consul Dónal Denham and gave the database to the institute to make it available to the public. I turned over directorship of the institute in 2009, and some years later the project folded and the database is no longer available online.

† This process of human “coding” of data for analysis has been used with interesting results in Gottschall 2008.

‡ There are other works that have attempted to encapsulate large segments of Irish American literary history. My own published work on Irish American authors in the San Francisco Bay Area, in Montana, and in the Midwest are fairly recent examples (Jockers 2004, 2005, 2009). Ron Ebest's Private Histories (2005), profiling several writers who were active between 1900 and 1930, is another.

* As both a reader and a former student of Charles Fanning, I am indebted to and deeply influenced by his work. My research has been aided by modern technology, and the number and variety of works that Fanning unearthed, without the aid of such technology, serve as a model of scholarly perseverance.

† I began collecting works for this database in 1993 as part of a study of Irish American writing in the West. The database has grown significantly over the years, and in my Irish American literature courses at Stanford, students conducted research in order to help fill out missing metadata in the records. Note that in all charts, data for the decade from 2000 to 2010 are incomplete.

* The limited amount of data here makes correlating the lines unproductive, even while there are some noticeable similarities. When linear trend lines are calculated, it is seen that production is slowly increasing over time, and the two trend lines are almost parallel, indicating a similar rate of overall increase.

* Elsewhere I have argued that it is most likely a combination of both factors (Jockers 2005).

* Census figures provide information relative only to first-generation Irish immigrants, whereas the publication data do not discriminate based on generational status. Thus, the authors of these books may be first-generation Irish immigrants or secondor third-generation American descendants of Irish immigrants. One assumption that is debunked by this data is that a steady influx of new immigrants would tend to perpetuate an interest in ethnic and cultural matters; the more new immigrants, the more one would expect to see a literary manifestation of Irish themes. On the contrary, the evidence suggests no correlation between immigrant population and the production of ethnically oriented fiction. Census figures are from the historical Census Browser, retrieved January 29, 2007, from the University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center, http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.html.

* My working assumption here is that there should be a connection between a writer's proclivity to write about the Irish experience in America and the strength of the Irish community in which the writer lives. More Irish-born citizens should mean more Irish-oriented books. Obviously, there are many other factors that could be at play here. Take, for example, economics. Would Irish writers in more vibrant local economies be more inclined to write? It is entirely possible. What is compelling and unquestionable here is the sheer number of Irish American books in the West—whatever the demographics.

† A total of 758 texts spread over 250 years is only about 3 texts per year on average, and in reality the number of texts from the earlier years is much fewer. To be conclusive, I think we would need a larger and more evenly distributed corpus of texts. Nevertheless, I suspect that this corpus approaches being comprehensive in terms of the “actual” population of texts that may exist in this category. In that sense, the results are convincing.

* An estimate of the area west of the Mississippi.

* It is important to point out that a primary aim of Fanning's work in the Irish Voice in America was to call attention to the works that best represent the Irish experience in the United States. Fanning sought to highlight not simply those works that most accurately depict Irishness in America but, more important, those works that depict the Irish experience with the greatest degree of craft and literary style. Fanning's success in identifying and calling our attention to many of the very finest authors in the tradition is decisive, and the matter of whether these new western writers are aesthetically comparable to their eastern counterparts remains an open question that I am taking up in another project. The lost generation Fanning discusses may indeed be a lost generation of high-quality writers. It is not my purpose here to further separate the books into classes based upon my perceptions of their aesthetic merit.

* See http://bld2.alexanderstreet.com (subscription required).

* I define “ethnic markers” to include words that a typical reader would identify or associate with Irish ethnicity. These markers include such obvious words as Irish, Ireland, Erin, Dublin, Shamrock, and Donegal as well as less obvious but equally loaded words and surnames such as priest, Patrick, parish, diocese, Catholic, Lonigan, Murphy, O'Phelan, O'Regan, O'Neill, O'Mahony, O'Donnells, O'Flarrity, O'Halloran, O'Shaughnessy, and so on.

* This is a point somewhat similar to the one made by Fanning in the context of the early 1900s.

† My critical introduction to Driscoll's novel can be found in the recent republication of Kansas Irish by Rowfant Press, of Wichita, Kansas, in 2011.

‡ The possibility that these titling patterns are publisher driven and not author driven has occurred to me. Publisher and publication place are also recorded in the metadata, and there was nothing found in those data to suggest that the trends were driven by anything other than authorial choice.

* Immigration here was male dominated.

* For more on optimism and the general success of the Irish in the western states, see Jockers 1997, 2004, 2005, 2009.

* Title length almost certainly plays a role here. As we move from past to present, the ten-year moving average for title length drops from roughly seventy-five characters before 1840 to fifty characters in the latter half of the nineteenth century and then to twenty to twenty-five characters after 1900.

* Obviously, some authors may not wish to stand out in the market at all. Quite the contrary, they may wish to capitalize upon the success of prior works and to follow the most lucrative titling trends.