7 NATIONALITY

The historical sense compels a man to write not merely with his own generation in his bones, but with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order.

—T. S. Eliot, Tradition and the individual Talent (1917)

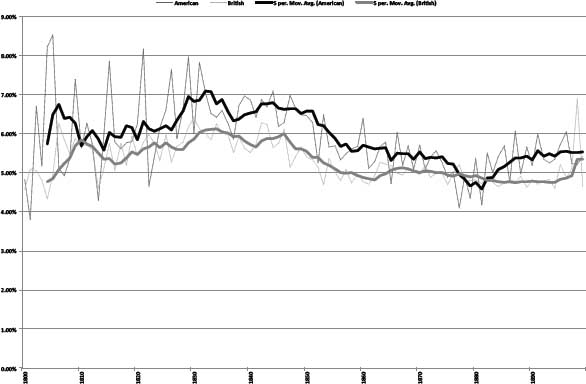

The previous chapter demonstrated how stylistic signals could be derived from high-frequency features and how the usage, or nonusage, of those features was susceptible to influences that are external to what might we might call “authorial style,” external influences such as genre, time, and gender. These aspects of style were explored using a controlled corpus of 106 British texts where genre was a key point of analysis. The potential influences or entailments of nationality have not yet been examined. Clearly, nations have habits of style that can be identified and traced. Consider, for example, the British habit of dropping the word the in front of certain nouns for which American speakers and writers always deploy the article: “I have to go to hospital,” says the British speaker. The American speaker says, “I have to go to the hospital.”* Given a linguistic habit such as this, it is no surprise to find that the mean relative frequency of the word the is lower in British and Irish novels than in American novels. In a larger corpus of 3,346 nineteenth-century novels that is explored in this and the following chapters, British novelists use the word the at a rate of 5 percent. For the American texts in this corpus, the rate is 6 percent. By itself, usage of the word the is a strong indicator of nationality, at least when trying to differentiate between British and American texts. In fact, using just the word the, the NSC classifier reported a cross-validation accuracy of 64 percent. That is, 64 percent of the time, the classifier can tell if a novel is British or American simply by examining the novel's usage of the word the. What is puzzling about the word the, however, is not that it is used almost a full percentage point more by the Americans than by the British but rather that the minor fluctuations in usage between the two nations are closely correlated over time. In other words, when in the course of the century British usage drops, American usage drops almost simultaneously. The fluctuations are not perfectly aligned to years, but they are close. When the data are smoothed, as in figure 7.1, using a five-year rolling average, the remarkably parallel nature of the two trends becomes apparent.*

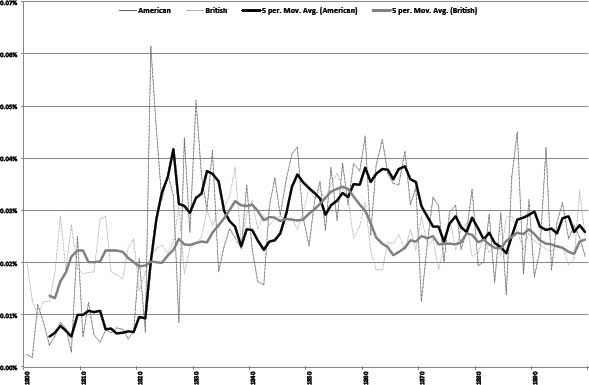

Over a period of one hundred years, it is as if the writers in these two nations—two nations separated by several thousand miles of water in an age before mass communication—made a concerted effort to modulate their usage of this most common of common words. However, the is not the kind of word that authors would consciously agonize over; quite the contrary, the is a trivial word, a function word, a word used automatically and by necessity. Whereas the use of the word beautiful, for example, may come and go with the fads of culture, the word the is a whole different animal. For comparison, consider figure 7.2, which charts the relative frequency of the word beautiful in the same corpus. Whereas the is nearly parallel, beautiful is erratic and unpredictable.

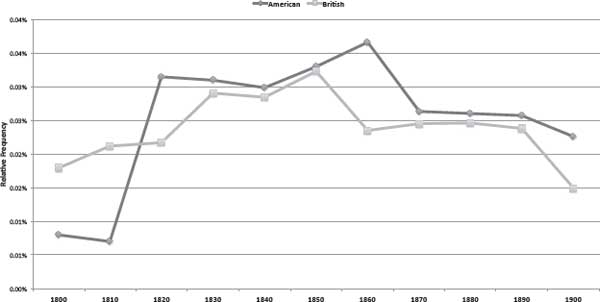

The degree of correlation between the British and American patterns can be calculated statistically using a “correlation coefficient.” A correlation coefficient measures the strength of a linear relationship between two variables: for example, we may wish to know the correlation between Montana's average winter temperature and the use of heating oil. To calculate this relationship, we can use the Pearson correlation coefficient formula, which takes the covariance of two variables and divides by the product of their standard deviations. The resulting value is a number on an “R” scale ranging from –1 to 1, where 0 corresponds to no correlation. The correlation coefficient for the year-to-year fluctuations between British and American usage of the is 0.382. For the word beautiful, on the other hand, the correlation coefficient is just—0.08.† The correlation coefficient of 0.382 for the word the is certainly not what would be considered an exceptionally “high” correlation. Nevertheless, when seen in the context of the irregular behavior of beautiful, the is comparatively stable. When we consider that the coefficient for the was calculated based on the year-to-year fluctuations, not upon the smoothed moving average seen in figure 7.1, its observed stability is even more remarkable. This coefficient of 0.382 is derived from tracking the year-to-year fluctuations and not the larger macro behavior. If, instead of taking the year-to-year means, we calculate the correlation coefficient based upon decade-to-decade averages, the coefficient rises to 0.92! By removing the year-to-year “noise” in the data, we observe the larger macro pattern more clearly, and the macro pattern of British and American usage of the word the is highly correlated. The decade results are charted in figure 7.3.

Figure 7.1. Usage of the word the in British and American novels

Figure 7.2. Usage of the word beautiful in British and American novels

So as to be clear about the calculations here, for each nation I begin by counting all of the occurrences of the in each decade and then divide by the total number of words in each decade. This returns the “relative frequency” of the usage in each given decade. The relative frequencies are then plotted chronologically from 1800 to 1900 to produce the trends seen in figure 7.3. When the fluctuations in the use of beautiful are similarly calculated, the correlation coefficient increases from –0.08 to 0.36 (figure 7.4).

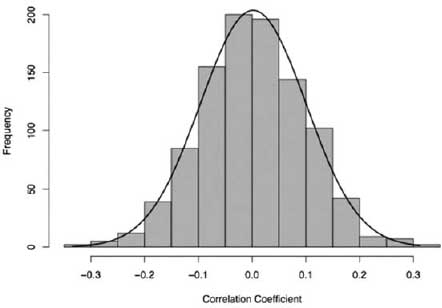

The pattern of tandem fluctuation seen with the word the defies easy explanation. My conclusion regarding this phenomenon is quite literally “to be determined.” Unless one is willing to entertain Rupert Sheldrake's notion of “morphic resonance,” then the behavior of the is downright mysterious.* I first observed this behavior of the in 2005 in a much smaller corpus of one thousand novels. After six years of contemplation, and twenty-five hundred more books, plausible explanations remain few and far between.† Perhaps these trends are brought about by publishers, or by editors, or by industry pressures, or by reader demand? None of these seems likely, given that the word in question is the. Surely, ten decades of American writers were not consciously adjusting their usage of this common function word in order to match British fluctuations—or visa versa—even though they were perhaps reading, editing, and discussing each other. Perhaps the distribution of these data is simply the result of chance, an anomaly of the data? To test the possibility that this correlation coefficient could have been derived simply by chance, I shuffled the year-to-year data for American usage of the one thousand times, such that with each shuffling, the values were randomized and no longer in chronological order. After each shuffling, a new correlation coefficient was calculated against the year-to-year chronologically arranged British data. The resulting coefficients, a thousand of them, were examined and plotted in a histogram. They followed a normal distribution centered around a coefficient of 0. The test confirmed that the 0.382 correlation coefficient was not likely to have been a result of chance (see figure 7.5).

Figure 7.3. Usage of the word the in British and American novels by decade

Figure 7.4. Usage of the word beautiful in British and American novels by decade

The mean correlation coefficient of these one thousand random iterations was just 0.005; the observed correlation coefficient, 0.382, is, therefore, nearly four standard deviations from the mean; that is, 99.7 percent of the distribution lies within +/- three standard deviations from the mean. In short, the probability of getting 0.382 correlation for the word the by chance is less than 0.01 percent.* For whatever reason(s), the behavior of the in these two national literatures is correlated in time. The important point is not that the two nations’ usage patterns mirror each other but, rather, that they do so in the context of this most unimaginative of words. Few would be willing to argue that these authors were consciously modulating their usage of the. A far more plausible explanation may be that the usage of the is secondary to some other unknown and shifting feature, a covariation in which changes in some unknown variable lead to the shifts seen in the known variable. The identity of the unknown variable remains an enigma, but the overall behavior surely indicates that there are forces beyond authorial creativity.

The behavior of the word the is, indeed, unusual. I found no other common word in the corpus that behaved in this manner.† What is clear about the word the, however, is that it is a very useful feature for distinguishing between British and American texts. Any given text in the corpus with a relative frequency of the near 6 percent is far more likely to be an American text than a British text. On the other hand, the word the is comparatively useless when it comes to distinguishing between British and Irish texts, and this, for reasons that will be made apparent soon, is the far more interesting problem.

Figure 7.5. Histogram of random correlation coefficients

W. B. Yeats once claimed that he could detect in Irish literature two distinct accents: “the accent of the gentry and the less polished accent of the peasantry” (1979, 9). One nation, two literatures: the first highly influenced by the British tradition and the other a more organic, “pure” style arising out of the native tradition. Could fluctuations in the use of a common word, such as the, be dependent upon whether an Irish writer was of the gentry or the peasantry? I am not inclined to make the same class distinctions as Yeats; I do not have the ear for accents that he did, and the business of defining who is of the gentry and who is of the peasantry is one better suited to poets than scholars. Nevertheless, Irish literature presents an interesting case, even as we leave the authors to their respective classes, unsegregated.

With his comments about distinct “accents,” Yeats vocalized a sometimes-latent tradition of thinking of true, pure Irish literature as that literature that possesses an authentic “Irish voice” (to use Charles Fanning's term). Yeats, perhaps less consciously, invigorated a practice of valuing or devaluing the merits of the Irish novel in terms of the extent to which the novels were authentically Irish or tainted by some form of “Dickensian” influence. The fault does not lie entirely with Yeats, but Yeats was bolder in his proclamations than other critics.* Writing of the Irish novel tradition in Samhain, he argued that “it is impossible to divide what is new and, therefore, Irish, what is very old and, therefore, Irish, from all that is foreign, from all that is an accident of imperfect culture, before we have had some revelation of Irish character, pure enough and varied enough to create a standard of comparison” (1908, 8). On this point, others, including Thomas Flanagan (1959) in particular and more recently and more generally Katie Trumpener (1997), have sought to define the nineteenth-century Irish novel not in terms of how it differed from or failed to mirror an English realist tradition but in terms of how it “anticipated” and “enabled,” as Joe Cleary writes, the twentieth-century modern novel and Joyce's Ulysses in particular (Bélanger 2005). Cleary goes so far as to suggest that the position of the Irish on the colonial periphery may have been the catalyst that compelled Irish novelists to be more innovative, inventive, and experimental than their British counterparts. Regardless of the side one takes in this debate—either that the Irish novel is different and, therefore, better, or that the Irish novel is different and, therefore, inferior—there is general agreement that something unconventional is going on with the novel in Ireland.

Irish literature scholars including Thomas MacDonagh (1916), Thomas Flanagan (1959), John Cronin (1980), and most recently Charles Fanning (2000) have commented upon distinct and specific uses of language that they believe characterize, or “mark,” Irish narrative as Irish. For some, this unique use of the language in Ireland is thought to be a by-product of the manner in which the Irish adopted (or were forced to adopt) English as a second language. In support of this contention, Mark Hawthorne has written that the “Irish were not accustomed to the English language and were unsure of its subtleties and detonations” (1975, 11). However, both Fanning and Cronin have argued, separately, that the Irish became masters of the English language and employed, in Fanning's words, a mode of “linguistic subversion” designed to counter or retaliate against forces of British colonization.* Still, none of these scholars gets to the heart of the difference, to the actual linguistic or stylistic data. Thus far, these speculations regarding Irish intonations and “accents” have been of the “you'll know them when you see them” (anecdotal) variety. These are hypotheses in need of testing, in need of macroscale confirmation or refutation, and the devil here is most certainly in the data. Let us see (or compute), then, to what extent a nineteenth-century Irish voice may be heard (or measured) amid a cacophony of 1,030 British and Irish novels.

Using techniques described in the previous chapter, I extracted the word-frequency data from the British and Irish texts in the corpus. I winnowed the resulting matrix to exclude words with a mean relative frequency across the corpus of less than 0.025 percent. A classification model was then trained on all of these data, and the word and punctuation features were ranked according to their usefulness in separating the two nationalities. Among the words found to be most useful was a cluster of words indicative of “absolutes” and words expressing “determinacy” or “confidence.” More frequent in British novels than in Irish novels are the words always, should, never, sure, not, must, do, don't, no, nothing, certain, therefore, because, can, cannot, knew, know, last, once, only, and right.* The British novels were also seen to favor both male personal pronouns and the first-person I and me.† Irish novels, on the other hand, were found to be most readily distinguished by words we might classify as being characteristic of “imprecision” or “indeterminacy,” words such as near, soon, some, most, still, less, more, and much.‡ Whereas the British cluster of words suggests confidence, the Irish cluster indicates uncertainty, even caution.

Equally instructive are the classes of words that are negatively correlated to nationality, that is, words that are relatively underutilized. Among the most underutilized words in Irish fiction are the words I, me, my, if, should, could, sure, and must. These are words in the first person and modal words suggestive of possibility or perhaps even certainty about the future. The comparative underutilization of first-person pronouns signals a preference for third-person narration but may also signal a concomitant lack of self-reflective narrative. The absence of the modal words seems to imply not only uncertainty about the future but also an inability to conceive of the future and its possibilities. What is comparatively absent, then, are words that would allow Irish authors to consistently express what “should” or “could” happen, what might happen “if,” and what “must” happen to “me.” This suggests, perhaps, that the narrative world of the Irish novel is one possessed of a general lack of agency, an observation lending credibility to several more impressionistic assertions made by Terry Eagleton. Among other things, Eagleton argues, the British realist novel is characterized by “settlement and stability,” whereas the “disrupted course of Irish history” led to Irish novels characterized by “recursive and diffuse” narratives, with multiple story lines and an “imperfect” realism (as cited in Bélanger 2005, 14–15). “Imperfect realism”: this makes me uncomfortable because it is a purely subjective observation, but even more so because the “imperfect” implies that “perfect” realism—whatever that might be—is the goal. The underlying assumption is that if Irish authors were not striving for perfect realism, then they should have been, and if they were, then they were failing. These are not questions with answers, only speculations. We can, however, observe what is in fact happening with language usage, and if we cannot measure perfection, we can at least measure and quantify the features that mark the two national literatures as different. Success here will lead us back again to the micro scale, where we can then legitimately ask a question such as this: which text in the Irish corpus is most similar to Eliot's Middlemarch?

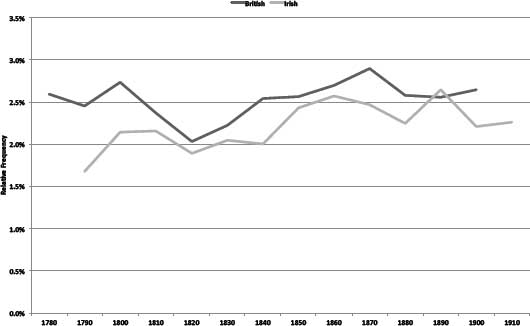

As was seen in the analysis of the word the, habits of word usage, conventions of prose style, are not frozen in time; they can fluctuate, and they can be charted. Figure 7.6 shows the aggregated relative frequency of the “British” words: always, should, never, sure, not, must, do, don't, no, nothing, certain, therefore, because, can, cannot, knew, know, last, once, only, and right. Here the cluster is plotted over the course of 120 years. In addition to upward trending seen in both lines beginning in the 1820s, what is remarkable is the way in which the usage of these features in the two national literatures tends to move in parallel with each other, reminiscent of the behavior of the word the in British and American novels. These data indicate that there are both national tendencies and extranational trends in the usage of this word cluster. The British use these words more often, but not necessarily differently from the Irish. Both national literatures are slowly increasing their usage of these “confidence” markers, and they tend to be doing so in parallel—with the Irish always slightly below the British. Unlike the word the, however, these are not solely function words. These words carry thematic, semantic baggage. What it is that is influencing this word usage is trickier to ascertain. Perhaps Irish culture is changing in such a way that Irish authors are writing more self-reflexive narratives. Or perhaps Irish authors are consciously imitating the stylistic shifts of their British counterparts, trying to “catch up,” as it were. If this cluster of words is in fact a surrogate, an abstraction, for some degree of stability and confidence, then we might hypothesize that over time, Irish prose is coming to express more confidence. Such a hypothesis makes for an interesting diversion: studying the trends more closely, we see only one place where the Irish line moves considerably in a direction opposite to the British, and this occurs in the 1840s, during the height of the Great Famine.* If Irish prose were to move toward expression of a lapse in confidence, a moment of doubt about the future, the famine would seem a fitting place to see such a shift.

Figure 7.6. The British word cluster over decade and nation

The temptation to “read” even more into these patterns is great. To go further, however, requires acceptance of the initial premise. We must agree that this somewhat arbitrary cluster of words—always, should, never, sure, not, must, do, don't, no, nothing, certain, therefore, because, can, cannot, knew, know, last, once, only, and right—is a reasonable proxy for some latent sense of confidence in British prose. Some readers will undoubtedly agree and require no further substantiation; others will argue that, when taken out of their context, it is impossible to correlate the frequency pattern of these words with a larger concept such as “confidence.” It will seem to some even more egregious to draw connections between these usage patterns and historical events, such as the Irish Famine. Assuming that we are unwilling to make the leap from word cluster to concept, it is nonetheless instructive to see which authors “excel” in the use of these terms. When sorted according to the usage of words in this cluster, we find among the top fifty novels four novels by Jane Austen and nine by Anthony Trollope.* Whether these two authors may be claimed as quintessentially British is a leap I will leave to readers; the data simply tell us that these authors have a particular fondness for words in this particular cluster.

Here I must acknowledge again that this particular cluster of words, although selected by the algorithm as strong distinguishers, was cherry-picked from among the full list of features the model found to be characteristic of British fiction. My cherry-picking ignored punctuation features, for example, as well as words that I deemed to be less meaningful (or whose meaning I did not immediately understand): the, this, had, and been, for example. Allow me, therefore, to put the cherries back on the tree, and let us see which novels in the corpus are most tellingly Irish and which most obviously British. The writer with a word-frequency profile that is most characteristically Irish is Charles Johnstone (1719–1800?). At first glance, this seems a surprising distinction; Johnstone was by no means provincial. Though born in Limerick, he traveled widely, living in London and Calcutta and writing books set in India, the Middle East, and Africa. Aileen Douglas argues that, though Johnstone “most strenuously advocates the ideal of Britain” (2006, 32), he is at the same time a satirist in the Swiftian tradition and a writer deeply committed to the critique of colonialism in Ireland. As we saw in the previous chapter, genre choices can often entail certain word-frequency patterns. Perhaps the critique of colonialism naturally results in an increase in the aforementioned “Irish” markers. In the list of most Irish writers, John Banim and William Carleton follow Johnstone in second place and third place. These two writers fit more easily into the prescribed rules for being “authentically” Irish. Banim was of the Catholic middle class and wrote what were essentially regional novels about the peasants in his home county of Kilkenny. Carleton, even more than Banim, was a man of “authentic” Irish bona fides. He was born of poor Gaelic parents in County Tyrone, and his first ambitions were toward the priesthood.

By this metric of word-frequency patterns, the least “Irish” of the Irish authors in the corpus are Maria Edgeworth, Bram Stoker, and Oscar Wilde. Edgeworth, though a pioneer of the Irish regional novel and an influence on Sir Walter Scott—who wished to attempt for his own country “something…of the same kind with that which Miss Edgeworth so fortunately achieved for Ireland” (Cahalan 1988, 16–17)—was also keenly aware that her audience was British; her prose is frequently aimed in that direction. The latter two, Stoker and Wilde, are frequently, conveniently, and too often mistakenly remembered as being British writers, not Irish ones.

On the other side of the Irish Sea, the most distinctly British authors were found to be Alan St. Aubyn, Mary Angela Dickens, and Margaret Oliphant. It is worth noting that the more familiar Trollope and Austen are not far down the list. Alan St. Aubyn, a pseudonym for Mrs. Frances Marshall, wrote women's “varsity novels” and was, according to Ann McClellan, quite popular at the end of the century. Her popularity, however, was forged through compromise. McClellan writes that “to get published, she had to appease men's fears; to sell books, she had to fulfill girls’ dreams” (2010, 347). In short, she gave the people what they wanted. Mary Angela Dickens, eldest daughter of Charles, was a novelist, a Londonite, and a devoted member of London society. Early reviewers are mixed in their opinions of her work: some appear to judge her on the “Dickens standard,” while others give her a pass in reverence to her lineage. Whether good or bad, she is most certainly a British author. Last among the top three is Margaret Oliphant, a Scot by birth who moved to Liverpool at the age of ten. Oliphant was prolific, and her work earned her the telling distinction of being “Queen Victoria's favorite novelist” (Husemann 2003, n.p.).

Least British according to this metric is William Hutchinson. Ironically, Hutchinson's most un-British novel is titled The Hermitage of Du Monte: A British Story. Hutchinson is followed by the apparently anonymous novel Llewellin: A Tale.* The book is dedicated to the then eight-month-old Princess Charlotte Augusta of Wales. Louisa Stanhope, a writer of Gothic and historical novels, follows the author of Llewellin in third place. Readers, such as myself, who are unfamiliar with these three finalists in the category of “least British of the Brits” may travel just a few steps up the list to find the more recognizable works of Sir Walter Scott: first Ivanhoe and then A Legend of Montrose. With Scott, a writer frequently corralled among the British (that is, not always thought of as a distinctly Scottish author), it would appear that the method has failed. Though Scott's themes were often British and Saxon, his style remained distinctly, undoubtedly, a by-product of his Scottish heritage and his early preoccupation with the oral traditions of his native Highlands.

Here we hit upon the end point of what this stylistic or linguistic feature analysis can provide in terms of separating writers by nationality. The most frequent words can take us no further. The classification procedure employed in this chapter revealed a number of features that were useful in distinguishing between British and Irish prose, but in the end, classification accuracy never rose above 70 percent. This result is neither surprising nor discouraging; it simply indicates that there are many similarities between the two national literatures and that stylistic habits of word and punctuation usage are an imperfect measure of national style—imperfect, but not entirely useless. They do take us part of the way, and they do reveal elements of prose style that are characteristic of the two nations. At the same time, the results show that the borders of prose are porous: influence knows no bounds. Should Scott, despite his Scottish “accents,” still be classed—as my former student Kathryn VanArendonk put it—among those whistling “Rule, Britannia”?† For this answer, we must now move toward thematics: if Scott does not write in a typically British way, does he at least write of typically British topics?

* Irish and Australian speakers and writers are similar to the British in using the less frequently.

* It is possible, perhaps even likely, that a larger corpus would show a similar level of smoothness on a year-to-year basis without the need to use a moving average. Some of the more dramatic year-to-year fluctuations seen in this corpus occur in years when there is only one text from one country and several texts from the other.

† A coefficient of 1 would indicate perfectly positive correlation: the two lines in the chart would be perfectly matched, or parallel. As one increased, the other would increase to the same extent and at the same time. Alternatively, a coefficient of -1 would represent a negative correlation: as one decreases, the other increases proportionally.

* Which is not to say that Sheldrake's observations are not likewise mysterious. Sheldrake's idea, which is in some ways similar to the notion of a Jungian collective unconscious, describes a telepathy-like interconnection between organisms within a species. In Sheldrake's conception, there are “morphogenetic fields” through which information is transmitted, as if by magic. Sheldrake's “theory” is designed to explain how change is wrought in subsequent generations, how successive generations of day-old chicks, for example, might become reluctant to perform some behavior because they “remember” the experiences of prior generations (Rose 1992; Sheldrake 1992). But even Sheldrake's questionable theory of morphic resonance fails to explain the fluctuations seen in these data. Unlike the chicks that are conditioned to behave in a certain way, there is no apparent stimulus here, either positive or negative. Given our formalist, even materialist, approach, Sheldrake's idea seems far too immaterial, too immeasurable, to put much stock in it.

† At one point, I believed the behavior was an aberration of the data, a result of having too small of a corpus. Thirty-five hundred more texts later, and the trend is the same.

* The p-value, calculated based on the t-test, is less than 0.0001, strong evidence against the proposition that 0.382 could have been derived by the variation in random sampling.

† Admittedly, I did not make an exhaustive search. I looked only at the ten or so most frequent words and then abandoned the search in order to return to my primary objective of exploring how style could be used as a discriminator of nationality.

* Margaret Kelleher (2005) makes it clear that there is a tradition of characterizing and criticizing the Irish novel by its failure or success (perceived or otherwise) to match the qualities of the ostensibly superior realist novel that “rose” to prominence in England.

* I can think of no better expression of this linguistic subversion in fiction than chapter 4 of Carleton's Emigrants of Ahadarra. Responding to the schoolmaster's inflated prose, Keenan replies, “That English is too tall for me…. Take a spell o’ this [and here he refers to the illicit poteen they have brewed] it's a language we can all understand” (1848, 36).

* A separate analysis determined that these words were also more frequent in British novels than in American.

† The significance of this fact will not be lost on postcolonial scholars who have argued that the colonial British tended to conceive of the Irish in feminine terms. See, for example, Howe 2000; McKibben 2008; Stevens and Brown 2000.

‡ Separate analysis revealed that American novels are distinguished from Irish and British novels by a higher frequency of concrete nouns and adjectives rather than abstractions: words such as heart, death, eyes, face, young, life, hand, and old are all more frequent in the American texts.

* In the 1890s, the Irish achieve usage parity, but unlike the 1840s, there is not a clear movement in opposite directions.

* Lady Susan, Emma, The Watsons, and Northanger Abbey by Austen and The Duke's Children; The Prime Minister; The Last Chronicle of Barset; Phineas Redux; Can You Forgive Her?; Phineas Finn, the Irish Member; The Way We Live Now; Doctor Thorne; and The Small House at Allington, by Trollope.

* “Apparently” because the author is listed as “Llewellin.”

† Ironically, the poem “Rule, Britannia” was written by the Scottish poet James Thomson.