ON JANUARY 31, 1866, the Native California Cavalry, until then stationed in the Arizona Territory, saddled up and began the long ride back to California. The Union had defeated the Confederacy, Napoleon III had set a timetable for withdrawing the French Army from Mexico, and Maximilian’s days were clearly numbered, so the California cavalrymen retraced their path across the desert. After arriving in Los Angeles, Companies A, B, and D were mustered out at the Drum Barracks in Wilmington on March 20, and Company C at the Presidio in San Francisco on April 2.1 But the Los Angeles to which these veterans returned was different from the city Francisco P. Ramírez had woken up in nearly twenty years earlier, transformed overnight into a citizen of the United States. Its Latino population had grown and diversified since 1848. The Gold Rush had brought tens of thousands of immigrants from Mexico, Central America, and South America to the state. Most did not find much gold, so they began a secondary migration, from the gold fields to other parts of the state, including Los Angeles, to find work. This surge of young Spanish-speaking adults fueled an increase in Latino marriages, and then a baby boom; Latino births nearly tripled during the 1850s and 1860s.2 During the American Civil War and the French Intervention, members of this generation of bilingual, bicultural children participated in activities inspired by the first battle of Puebla. Children had even participated spontaneously in the first officially sponsored commemoration of the battle, on May 25 and 26, 1863.3

Some parents formally engaged their children in the juntas. In July 1863, the president of the Los Angeles junta, Gregorio González, enrolled his son, Gregorio Jr., as a member.4 In February 1863, Jesús Villanueva de Williams, a member of both Los Angeles’ regular junta patriótica and its ladies’ junta, enrolled her eleven-year-old daughter, Manuelita Williams, in the latter.5 Some of these children took an active part in the juntas’ activities, including celebrations of the Cinco de Mayo. In the town of Sonora, Rosaura Soto first appeared as a member of the ladies’ junta late in 1863; during the 1864 commemoration of the Cinco de Mayo, she was in the chorus that sang the Mexican national anthem and later read a poem aloud.6

By 1870, the Latino population of Los Angeles was increasingly U.S. born, bilingual, and bicultural. This change was most evident among children and adolescents: more than 90 percent of Latinos under age twenty had been born in California. Adult Latinos twenty to forty-nine years old were about evenly split between U.S.-born Californios and immigrants. People age fifty and above were predominantly Californios, with a small minority of immigrants.

The war years had challenged this Latino community of Californios, post-1848 immigrants, and their second-generation children to develop and assert a shared public identity as defenders of freedom and democracy in both the United States and Mexico. With the formation of the juntas, the Latino community met this challenge, and in the celebration of the Cinco de Mayo, members of the large and wealthy junta in Los Angeles discovered a poder convocatorio (summoning power) that could harness the collective efforts of the Latino community toward specific ends (see chapter 4). As long as this power belonged to these Latinos and their children, the holiday’s genesis was remembered, but in subsequent generations, demographic developments caused it to pass out of their hands, and the Cinco de Mayo was reshaped by those with no memory of its origins.

For nearly twenty years after the Civil War and the French Intervention, war veterans and their civilian contemporaries in Los Angeles’ junta shaped the public memory of the Cinco de Mayo. Their celebration in 1877 shows how they, and the organizations to which they belonged, preserved memories of its origins. José López was the president of the junta that year and accordingly served as master of ceremonies for the event.7 At 6 A.M., the Mexican and United States flags were raised in front of López’s house to the sounds of artillery salvos and a band playing patriotic tunes. The cannon were fired again at noon. At five in the afternoon, officials assembled on the speakers’ platform, and the public crowded about to listen. López introduced one Señor Villalobos, who gave “an eloquent speech referring to the celebration of the day.” He was followed by a war veteran, Melitón Alviso, who had accompanied Uladislao Vallejo in 1866 in joining the Mexican Army (see chapter 5) and had fought the French in Mexico. Alviso’s speech was not printed but likely alluded to his experiences defending freedom and democracy there. At 6 P.M., the flags were lowered, and a local Latino militia, the Rifleros de Los Angeles, escorted the junta’s officers to the home of Antonio Aguilar for another flag-saluting ceremony and more speeches. After these formal ceremonies concluded, the Guardia Hidalgo, another Latino militia group, held a lavish, well-attended dance (see figure 22).8

FIGURE 22. A Cinco de Mayo ball held in Los Angeles in 1877 brought together former foes such as Melitón Alviso, a Californio from the Bay Area who had fought the French in Mexico, and his fellow Californio Ygnacio Sepúlveda, formerly a magistrate in Maximilian’s empire. (La Crónica, May 5, 1877, p. 2. CESLAC UCLA)

As Latinos born in Los Angeles between 1848 and 1870 came of age and took their places in adult society, a number joined their parents’ organization, the local junta. In so doing, they were directly connected to living Latino history and direct memories of the Cinco de Mayo. The lawyer Antonio Orfila Jr. was born in Los Angeles in 1865, the child of a post-1848 immigrant from Spain, Antonio Orfila Sr., and a California-born Latina mother, María Antonia Domínguez. From the time he was twenty-one until at least 1909, he participated in junta activities and ceremonies, including Cinco de Mayo celebrations.9 Orfila was joined in high-profile junta participation by his fellow second-generation Latinos Rafael “Ralph” Domínguez and Frank Domínguez in 1890 and Ignacio I. Pérez in 1891.10

All four were members of the junta alongside the former California governor Pío Pico, and this experience gave them a direct connection to pre-1848 Latino history in California. Pico was born in 1801 at the San Gabriel Mission complex, near Los Angeles. He lived in California under three governments—Spain’s, Mexico’s, and the United States’—and filled multiple official and public roles during his ninety-three years. In 1885, for example, still recognized as the “ex-Governor of Alta California,” he was a member of the Reception Committee that planned Mexican Independence Day festivities.11 Once the Cinco de Mayo became a public ceremony in Los Angeles, Pico participated in that as well, for instance as a member of the Reception Committee for the ball held in honor of the “Glorioso 5 de Mayo” in 1877.12 Other older members of the junta were fellow Californios; yet other, middle-aged members of the junta were post-1848 immigrants. They all worked together to organize public commemorations, initially for Mexican Independence Day celebrations. For instance, the Colombian immigrant Píoquinto Dávila participated in Cinco de Mayo celebrations from 1864 through 1873 and also was prominent in the junta’s Mexican Independence Day celebrations from 1865 to 1874.13

Second-generation Latinos thereby rubbed shoulders with the older generations as the latter shaped the public memory of the Cinco de Mayo. Yet when the Los Angeles junta’s attention shifted away from the commemoration of the Cinco de Mayo in the early 1880s to concentrate its energies on Mexican Independence Day (September 16), the second-generation Latinos did not allow the Cinco de Mayo to fade. Instead, they took upon themselves the continuation of the public memory and, in so doing, continued to shape it. In mid-April 1882, a group of young Latino amateur actors in Los Angeles presented a Spanish play, No Más Mostrador, to sufficient local acclaim that they were asked to repeat the performance. The repeat performance fell on May 4, so the group dedicated it to the Cinco de Mayo and made a few adjustments in keeping with the holiday. The performance ended by ten-thirty at night, followed by a dance, and at midnight a chorus sang the Mexican national anthem.14 In 1883, as advertised in the English- and the Spanish-language press, there was a “Glorious 5th of May Ball for the Benefit of the Union Brass Brand of Los Angeles,” with the funds raised going to purchase new uniforms.15 The next year, a group of mostly second-generation Latinos calling themselves the Jóvenes Hispano-Americanos (Hispanic American Youth) sponsored a Cinco de Mayo dance at Nadeau Hall (see figure 23).16

FIGURE 23. Los Angeles hosted a Cinco de Mayo event in 1884 organized by the Hispanic American Youths. This group included Juan Francisco Guirado, one of the first Californios to volunteer for service in the Union Army during the Civil War. He died in Los Angeles in 1886. (La Crónica, May 3, 1884, p. 3. CESLAC UCLA)

Beginning in the 1870s, these second-generation Latinos married and had children, producing a third generation. Leo Carrillo was born in 1880, a descendant of an old Californio family that included members of the original expedition to Alta California in 1769, a Mexican-era governor, and a signer of the 1849 California constitution.17 Myrtle Gonzalez was born in 1891 to Manuel González, a second-generation Latino of Californio parentage born in 1869, and his Irish American wife, Lilian Cook.18 Typical of third-generation Latinos, these children grew up familiar with Atlantic American culture yet also connected to Latino society, especially to the heritage of pre-1848 Mexican California. Early Californian songs, for instance, were part of their personal repertoire. In a 1904 musical recital, Myrtle Gonzalez was among the members of the La Golondrina Club, who performed old California dances and songs that included “El Sombrero Blanco” and “Los Camotes.”19 Had these third-generation Latinos been the only ones to continue shaping the Cinco de Mayo tradition, twentieth-century celebrations might have perpetuated the memory of Latinos during the American Civil War and the French Intervention in Mexico (see figure 24).

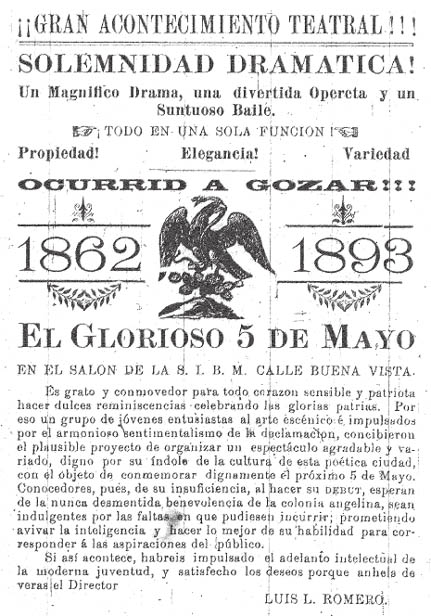

FIGURE 24. A group of second- and third-generation Latinos in Los Angeles organized an amateur zarzuela production in 1893 to commemorate the Cinco de Mayo. José S. Redona, a son of Lt. José Redona of Company D, Native California Cavalry, had one of the roles. (Las Dos Repúblicas, insert, May 1893. CESLAC UCLA)

Yet the junta began to lose its summoning power around 1910. This prompted second- and third-generation Latinos in Los Angeles to form the Sociedad Hispano-Americana (Spanish American Society), to better institutionalize the public memories they had been shaping. This new organization was responsible for the celebration of the Cinco de Mayo and Mexican Independence Day in Los Angeles from 1910 to 1923. A group of second-generation Latinos who rose to positions of leadership between 1883 and the 1920s supplied the direction: Antonio Orfila Jr., Ralph Sepulveda, Frank Dominguez, Ignacio I. Perez, Manuel González, and Ralph J. Dominguez.20 At the same time, the third generation of U.S.-born Latinos was entering its prime. But they were not to shape the Cinco de Mayo as their parents and grandparents had; instead, they ended up participating in someone else’s reshaping.

A renewed wave of immigration beginning in the 1890s brought a fresh population of first-generation immigrants from Mexico, whose experiences in California took the Cinco de Mayo in different directions. Los Angeles nearly quintupled in size, from 101,454 inhabitants in 1890 to 504,131 by 1910, finally overtaking San Francisco in population.21 The first immigrants in this period came to find work, but then the Mexican Revolution (1910–1930) sent massive numbers of refugees to California, fleeing political and social instability in their homeland. This huge new wave of immigrants dwarfed the population of U.S.-born Latinos and by the mid-1920s had taken over the shaping of the Cinco de Mayo. As the immigrants settled in, they formed a new type of organization, the mutualista (mutual aid society), which provided rudimentary benefits for its members, such as burial insurance. These were first organized in the 1910s and flourished in the 1920s and 1930s.22

These new groups soon recognized the potential of the Cinco de Mayo’s summoning power to help them, and they began to sponsor Cinco de Mayo celebrations. In so doing, they reshaped the holiday’s meaning to reflect their own experiences and perspectives. In 1918 the Liga Protectora Mexicana de California (Mexican Protective League of California), an early civil rights group for first-generation immigrants, held an event concentrating on inspirational speeches about the first battle of Puebla (see figure 25).23 The 1919 celebration at the Plaza organized by the Comité Mexicano de Festejos Cívicos (Mexican Committee on Civic Festivals) was the first one documented that was completely of, by, and for first-generation immigrants recently arrived from Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. The music was Mexican, not Californio, for that audience would not have been familiar with old Californio traditional songs such as “Los Camotes” or “El Sombrero Blanco,” although these still played at the celebrations held by the Sociedad Hispano-Americana.24

This was an era in the United States before Latino academia had found its voice, so there were no institutional means through which new immigrants could learn what second- and third-generation U.S.-born Latinos had lived. About the only institutional voice for Latino communities was Spanish-language newspapers, but as recently arrived immigrants published most of these, like Los Angeles’ El Heraldo de México, the greatest part of their focus was on Mexico and events in that country, not the experiences of past generations of Latinos in California. As a result, in the early twentieth century, two types of Cinco de Mayo celebration bypassed each other. The California-themed Cinco de Mayo event, built on memories dating back to the Gold Rush and the Civil War, gradually passed out of existence as second-generation Latinos died out. A new, Mexico-themed event instead emerged in the growing communities of recent immigrants, to reflect their experiences. Those first-generation immigrants—unaware of the holiday’s origins in Latino California or its links to the American Civil War, and understanding only that it celebrated the first battle of Puebla—began to define the Cinco de Mayo in purely Mexico-centric terms. The general image presented in Cinco de Mayo speeches given at first-generation events during the 1920s and 1930s was that of small, hard-pressed Mexico standing up alone against the might of a European power. A David and Goliath theme emerged, of near-miraculous victory against overwhelming odds.25

FIGURE 25. In 1919, the Mexican Protective League of California advertised its Cinco de Mayo event in a Los Angeles paper. In 1925, the league gave an award for community service to Reginaldo del Valle, whose life spanned the first seventy-five years of Cinco de Mayo celebrations in Los Angeles. (El Heraldo de México, May 6, 1919, p. 6a. CESLAC UCLA)

To keep the definition, and the summoning power, of holidays such as the Cinco de Mayo in the hands of this first-generation immigrant community, the Mexican consul Rafael de la Colina in 1931 appointed a Comité Mexicano Cívico Patriótico de Los Angeles (Mexican Patriotic Civic Committee of Los Angeles) to organize their celebration. This committee continues to function in the twenty-first century.26 The new Mexico-centric mythology promulgated by Mexican consuls and the first-generation immigrant press contributed mightily to the loss of public memory about the Cinco de Mayo’s true origins, which increased as the twentieth century progressed. The early twentieth-century wave of immigrants had successfully captured and reshaped the holiday, redefining it just as they redefined Latino culture in Southern California. By the 1930s the older, second-generation organizations, Los Angeles’s junta patriótica and the Sociedad Hispano-Americana, ceased to function. As a result, many third-generation Latinos, such as Leo Carrillo, instead came to participate in Cinco de Mayo activities organized by immigrant groups and the Mexican consul.

When the Axis Powers threatened freedom and democracy on a global scale in World War II, the celebration of the Cinco de Mayo seemed too important to leave in the hands of independent community organizations. Its summoning power could be harnessed to assist the war effort, and Los Angeles mayor Fletcher Bowron undertook to do just this. Under his direction, the Cinco de Mayo was elevated to an international event. On May 5, 1942, Mayor Bowron raised the Republic of Mexico’s banner in front of City Hall. The Mexican consul Rodolfo Salazar raised the Stars and Stripes beside it as the United States Army’s 16th Artillery Battalion band played the Mexican national anthem and more than five thousand Latinos witnessing the event cheered. In his remarks, Bowron emphasized that the Cinco de Mayo commemoration that day would show the world that the United States and Mexico were united in defending democracy.27 California governor Culbert Olson then took the microphone and recalled the history of the American Civil War and the French Intervention, developing the theme of two nations simultaneously under attack by the enemies of freedom and democracy, first in the 1860s and again in the 1940s. “Now, eighty years later, the fellowship of the two sister nations is felt again, and in the face of a common enemy that threatens this continent, the two peoples again toast their brotherhood and cooperation.” He concluded with the rousing cheer ¡Viva México y los Estados Unidos! (“Hurrah for Mexico and the United States!”).28 As the mayor of Los Angeles and officials of the U.S. and Mexican governments jointly shaped the Cinco de Mayo and explicitly enlisted its summoning power against the enemies of freedom and democracy, thousands of second-generation Latinos in the United States, the children of the 1910–1930 immigrants, responded by joining the U.S. armed forces.29

After the war, second-generation Latino veterans came home and formed families. Their third-generation Latino children grew up in the segregated California of the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s. Influenced by movements such as the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War protest movement, and the Farm Workers movement led by César Chávez, a good many of this cohort came of age questioning and even challenging California society’s perceptions of Latinos and the public policies based on those perceptions. Due to its sheer size, this third generation influenced many other segments of Latino society.30 It is not surprising, therefore, that almost from the beginning, this generation also challenged previous definitions of and ways of celebrating the Cinco de Mayo. The 1970 Cinco de Mayo event at the University of California, Irvine, was described as “a five-day program by Mexican-American students at UC Irvine on trends and problems of Chicanos in California.” Its activities included “panel discussions on education, the Delano [farmworker] strike and the Chicano movement, films and an outdoor dance.”31 Many Los Angeles–area college campuses likewise extended the celebration of the Cinco de Mayo over an entire week, which at Occidental College was called Semana de la Raza (Latino People’s Week) and at Chaffey College was called Chicano Week.32

Yet another wave of Latino immigrants settled in California between 1965 and 1990, many of whom had lived there before, when they were recruited from Mexico as braceros (guest agricultural workers) in the early days of World War II to grow the state’s food while the bulk of its men were in the armed services and its women worked in defense industries (see figure 26). Once the war ended, the braceros’ assistance continued to be so valuable that the program was maintained throughout the Berlin airlift, the communist victory in China, the Korean War, the Cuban revolution, and the raising of the Berlin Wall. Year after year, nearly half a million braceros traveled north to tend crops that fed much of the United States. When the program expired in 1964, it was soon discovered that agricultural labor was still sorely needed. Consequently, the United States again allowed regular Mexican immigration in 1965, and many braceros returned to their jobs, but with a different legal status. Now they were immigrants, able to settle, buy a house, and raise a family. From the mid-1970s, they were joined by refugees fleeing the violence that wracked El Salvador, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Honduras.

It took nearly two decades, from 1965 to around 1985, for braceros to fully change their status to that of immigrants. In the 1980s, they invented a new kind of first-generation community organization, the Mexican Home Town Association (HTA). Immigrants hailing from the same town or village in Mexico came together in California to form a club, whose main purpose was to raise funds to be sent to their native town. There, the money was used to build public works and provide services not being supplied by Mexican federal or local authorities, such as street paving, running water, or a town ambulance. An HTA therefore is reminiscent of a nineteenth-century Californian junta patriótica, only operating on a smaller scale and for local, purely peaceful purposes.33

As the new group of first-generation immigrants settled in, they discovered, as previous generations of immigrants had done before them, a strange new holiday in California, the Cinco de Mayo. Its summoning power soon became apparent to them, and the HTAs embraced it. For example, the Federación de Clubes Zacatecanos (Federation of Zacatecan Clubs) solemnly laid a wreath in Los Angeles’ Lincoln Park on the Cinco de Mayo, 2010, at the monument to General González Ortega, who finally had had to surrender Puebla after the city’s second heroic defense, in 1863.

FIGURE 26. Both U.S. and Mexican authorities used the Cinco de Mayo to foster support for the fight against the Axis powers in World War II. Braceros participated in these celebrations, such as the one in Whittier in 1945 referred to in this article. (La Opinión, May 4, 1945, p. 3. Courtesy La Opinión)

Yet why this day should be so enthusiastically celebrated in California was a mystery to them, as it was to nearly everyone by this time. “This date has little relevance in Mexico, which considers September 16 its national holiday,” noted an article in the Spanish-language newspaper La Opinión in 1986.34 Newspaper editors and public figures could say what the Cinco de Mayo holiday was not, but they were at a loss to explain its true meaning or where it had come from. Provided by Southern California’s immigrant-dominated Spanish-language press only with the Mexico-centric David-and-Goliath narrative presented annually under the auspices of the Mexican consulate, they naturally—albeit incorrectly—assumed that this festival must be some peculiar local adaptation of a purely Mexican holiday. “One of the great traditions that has come to the United States from Mexico is the celebration of the Cinco de Mayo,” declared William Dávila, then the president of Southern California’s supermarket chain Vons, in 1994.35 It did not seem to occur to anyone that the commemoration of the first battle of Puebla might have originated in California.

In the second half of the twentieth century, big business also discovered the Cinco de Mayo’s summoning power. Companies saw that the holiday’s public celebration offered an excellent opportunity to expand into the Latino market via the sponsorship of musical or other cultural events. Consequently, by the 1980s, corporate influence was noticeable in the holiday’s celebration. In 1990, the owners of the Spanish-language radio station KMQA-FM introduced a new order of magnitude by creating the L.A. Fiesta Broadway. The main streets of downtown Los Angeles were closed and large stages erected where prominent musicians performed. A major corporation, such as Sears, Target, or AT&T, sponsored each stage. Generally held the weekend before the Cinco de Mayo, L.A. Fiesta Broadway billed itself as “the biggest celebration of the Cinco de Mayo in the nation.”36

The demographic growth of the Latino electorate moved national and local political interests to try to claim the Cinco de Mayo’s summoning power in hopes of winning the Latino vote. In 1998, for example, the United States Post Office released a special Cinco de Mayo stamp featuring the image of two folklórico dancers—the man somewhat oddly wearing a modern charro suit, while the woman was in a traditional “Adelita” dress.37 In 2005, President George W. Bush brought the Cinco de Mayo to the White House. As mariachis blared in the Rose Garden, he thanked the Latinos serving in the nation’s armed forces and noted recent Latino contributions to the national economy, also stating, “Here at the White House, the triumph of the Cinco de Mayo was recognized by President Abraham Lincoln.”38 Like many others, however, the president appeared to be unaware that Latinos also had fought for the Union in the Civil War or that the Union and Juarist causes had identified with each other, as those facts went unmentioned.

Yet even while some corporate and political interests attempted to lay claim to the holiday’s summoning power, there were other interests that rejected the idea of celebrating a holiday they mistakenly perceived as foreign and somehow un-American. This viewpoint was encapsulated in a post to an online political chat list just before May 5, 2007, in a historically and grammatically challenged response to the poll question “Should Cinco de Mayo be celebrated in America?”: “I say no! Its an mexican independance day when Mexico declared its independence from Spain. It should be celebrated in their country not in america. A lot of illegals celebrate it here in america. I would like to see a law no promoting Cinco de Mayo in america. Any one celebrates this on May 5th in any american city or town faces a fine of $500 plus 5 days in jail.”39

This book was written to answer the question of why the Cinco de Mayo is so widely celebrated in the United States yet receives only perfunctory notice in Mexico. The answer is that it is not a Mexican holiday inexplicably adapted by Latinos in the United States nor, despite its undeniable commercialization in the late twentieth century, a fake holiday recently invented by beverage companies. Rather, it is a genuine American holiday, spontaneously created during the Civil War by ordinary Latinos living in California—soon echoed by others in Nevada and Oregon—as an expression of their support for freedom and democracy throughout the Americas. Far from being foreign or un-American, it originated in a devoted adherence to these basic American political values by the majority of Latinos in the United States, as well as Mexico and other republics in the Western Hemisphere, at a time when those values were under attack from within and without. It should be remembered that from the beginning, Cinco de Mayo parades have flown the U.S. and Mexican flags side by side as symbolic of this fact. That tradition is still followed today, although the reasons are largely forgotten.

It is interesting to speculate about what form future celebrations of the holiday might take, should its true origins and heritage become better understood. Naturally, the blatantly commercial aspects will not disappear; by now, virtually no American holiday has escaped some degree of commercialization. But future celebrations might also include Californio mission-era songs, dances, and costumes; uniformed Civil War reenactments featuring the Native California Cavalry and the unofficial Latino militias; images of Abraham Lincoln, Benito Juárez, and Ignacio Zaragoza; and of course liberal displays of American and Mexican flags side by side. Likewise, there might be uniformed reenactors of the French Intervention, including the Californios and Latino immigrants who traveled to fight for freedom and democracy in Mexico. In addition to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” one might hear Mexican soldiers’ songs of the 1860s, such as “Adiós, Mamá Carlota” or “Batalla del Cinco de Mayo.”40 It might be fitting as well to remember the Latinos who, in the same spirit, fought for the United States in the Spanish-American War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and subsequent conflicts. As in the nineteenth century, there might be speeches and pageants recalling these historical events, reminding listeners of the motivating values they share, showing the continuing relevance of those events and values to modern-day issues.