Chapter 16

Melville’s Basement Tapes

John Modern

Industrial technique will soon succeed in completely replacing the effort of the worker. . . . The worker, no longer needed to guide or move the machine to action, will be required merely to watch it and to repair it when it breaks down.

–Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society (1953)

Resonance

In her essay “A Theory of Resonance,” Wai Chee Dimock argues for the treatment of “literature as a democratic institution” and against “the primacy of the eye in the West” in favor of how a text “sounds” in and through time.1 What she is after is nothing less than the historicity of a text—its place within history as both a resource and a spur, as shaped by and simultaneously shaping a particular context. Following her methodological example, treating Moby-Dick as a “diachronic object” allows one to chart its behavior across time, exploring the changing energy of the text. Dimock advocates an approach that “acknowledges that the hermeneutical horizon of the text might extend beyond the moment of composition, that future circumstances might bring other possibilities for meaning,” and that the “passage of time . . . can give a past text a semantic life that is an effect of the present, rather than of the age when the text was produced” (Dimock, 1060–61). Such a disruptive temporality was, of course, charted by Walter Benjamin, who, in “Literary History and the Study of Literature,” insisted that the entire life and effects of a text—its receptions, translations, and fame—must stand beside the moment of its composition. He called for a deep contextualization of a work’s reception history in order to examine how it had been used in the past to reimagine social, political, and economic realities.2

A proper history of Moby-Dick, then, is a history of our reading of it and the daily barrage of technological designs seeking to coassemble thinking and feeling and to otherwise turn a human being into an algorithmic proposition. Such a history must account for the prophetic character of Melville’s text—in its anticipation of machines that think, in its anxious concerns over whether we will love our robot children, in its seeding of perspectives on the politics of technological society. In what follows I seek to conjure a particularly resonant conversation about Moby-Dick that shares Melville’s sense of the technological surround. For there is a pressing case to be made that Moby-Dick remains our last, best chance at surviving the catastrophic consequences of our mechanical advance.

Harpoon Hall

In August 1969 Howard P. Vincent organized a 150th birthday celebration for Herman Melville at Kent State University with guest speakers Henry Murray and Harrison Hayford and a cocktail hour held at Twin Lakes Country Club. A buttoned-up English professor with a shock of white hair, Vincent was a visible presence on campus in the late 1960s. His scholarly reputation was largely based upon his deep dives into the textual fundament of Moby-Dick. In the spring semester of 1975 he capped his three decades of Melville scholarship by curating Melville and the Creative Whale: A Display of Prints and Artifacts. As Vincent looked back he explained that the first time he read Moby-Dick, everything changed. “I went through a complete transformation trailing that white whale. . . . It was a great transforming experience for me.”3

Vincent’s so-called conversion resulted in The Trying-Out of “Moby-Dick” (1949), part of a midcentury wave of scholarship that had helped secure Melville’s genius during a particularly intense moment of canonization.4 In Trying-Out Vincent presented an exhaustive analysis of Melville’s knowledge and use of whaling sources.5 Vincent was an unapologetic antiquarian when it came to dissecting the mechanics of Melville’s genius. He homed in on Melville’s sources with a learned dexterity. Somewhat predictably, Vincent framed Melville’s creative reading of source materials as representative of an enduring feature of the American character. In his exhaustive attempt “to show Melville’s artistic enrichment of mundane fact,” Vincent sought nothing less than “to suggest the universal meaning of Moby-Dick” (Vincent, 8). No wonder Vincent was among those whom Charles Olson called “grubby young monks of university research.” Olson was explicitly dismissive of Vincent because he had “dirtied” Melville—and had been celebrated by Time magazine for it!—by weighing Moby-Dick in terms of its past life as opposed to the not yet.6 Critics like Vincent, Olson quipped, were unable to say “forward things” or grasp “the heroic principle in man.”7

Despite Olson’s barb, Trying-Out remains a helpful source guide as much as a window into Vincent’s obsession with Melville’s material relationality and self-environment complex that produced the articulation of Moby-Dick—what Melville was thinking, what books he read, when he checked them out from the library, what sections of writing correlated with their reading, the precise chronology in which Melville’s adventure story became something else, cut with the science and arcana of whaling and sustained metaphysical speculation.

With the reading life of the mind and the writing put side by side on his desk, Vincent hoped to gain access to Melville’s style of democratic cognition. According to Vincent, Melville’s “struggle for artistic freedom” was a civic ideal. His act of dexterous integration challenged Ahab’s monomaniacal will to power. In terms of criticism, Vincent was after the authorial fundament of Moby-Dick, the mechanics if you will, of actuality turning into truth, of a writing life turning into a novel of gigantic proportions (Vincent, Trying-Out, 162, 3).

On the one hand, Vincent’s scientific pose—isolating and measuring Melville’s creativity—is a defensive move to keep the material world at bay, an end-around affirmation of the primacy and purity of the human spirit. As Melville did in Moby-Dick, Vincent was able to achieve a measure of distance from his source materials, standing apart from them and controlling them from a distance. A steersman by any other name. On the other hand, Vincent’s relentless focus on the mechanics of material circulation—what Melville was reading, when he was reading, and how he translated those readerly insights into writerly newness—threatened to subvert Melville’s authorial integrity.

Vincent’s argument for Melville’s creative authority does not necessarily square with Vincent’s systematic documentation of it. Indeed, the primary payoff of Vincent’s book is that Melville’s creativity—his unexpected narrative turns, his writerly improvisations, his style of open-mindedness and autonomous judgment—was not entirely his own. The “great spiritual theme of Moby-Dick,” declares Vincent on the final pages of Trying-Out, “exemplifies the paradox of Christian doctrine that a man must lose his life to save it” (162, 163). With a nod to Father Mapple’s sermon, Vincent ends his book on a theological note of submission to powers that strike the senses as otherworldly.

So while Trying-Out argued for Melville’s masterful feat of literary control even as it practiced its own second-order version of it—Vincent’s method begged the question of the source of Melville’s imagination. Did it lie within or without? Where, if at all, could it be precisely located? Was it to be found in the typeset pages of Moby-Dick or, rather, in Melville’s losing himself in his “fish documents,” the vast majority of them copied, collected, and stored in Vincent’s basement? Might this question, with its strange implications and temporality, address Olson’s concern about the lack of futurity in the work of mainstream Melville scholars at midcentury?

According to a local reporter in her review of Melville and the Creative Whale, Vincent’s fervor for his whaling collection, begun in the early 1940s, was rather intense: “The day that Vincent first read the first line of Moby-Dick,” she observed, “also was the first day of the rest of his life as a whale trophy hunter. His lifestyle grew in that direction. Vincent’s home, for example, has an aura rather more native to Nantucket or New Bedford, Mass., than to Ohio. The basement (‘Harpoon Hall’) resembles more the hold of a ship than a basement.”8

By the late 1960s Vincent’s collection had become notorious among Melville scholars. Arranged somewhat haphazardly in the basement of his home in Kent, Ohio, Vincent’s archive was excessive in scope and overwhelming in volume: lithographs, paintings, and photographs on the wood-paneled walls; wooden figureheads from the prows of whaling ships; harpoons; scrimshaw; whale teeth and sextants; a mounted whale pan bone (the unseen part of the sperm whale jaw); a six-foot narwhal tusk; shelves packed with whaling books and captain’s logbooks; Moby-Dick comic books, articles, and clippings; and auction catalogs from dealers of whale jewelry and ephemera.

Howard P. Vincent, in “Harpoon Hall,” circa 1970. Howard P. Vincent Papers, Kent State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives.

Stuffed onto Vincent’s shelves were items that signaled other kinds of technical incursion from the world above:

- A crumbling draft of Vincent’s article on Basic English in which he chronicles attempts, before the formal advent of information theory in the late 1940s, to universalize human communication and to define “a universal psychic mechanism to guarantee its global reach.”9

- A photocopy of an article that begins with an ominous quotation from the director of the New Bedford Whaling Museum: “Statistics and scientific interpretations of those statistics, plus the world whaling industry’s persistent refusal to accept drastic conservation requirements, suggest strongly that Moby Dick may well be doomed.”10

- An article in which the author confronts “automated whale slaughter” and exhibits a nostalgia for a time when the sperm whale was the most powerful entity in the sea. “Yankee whalemen,” he writes, “with their crude methods, are gone, but a new type of grim, industrialized slaughter has replaced them. Today, Soviet and Japanese whaling ships, equipped with aerial observers, sonar, sure-fire killing devices, and floating factories, harvest whales in phenomenal numbers.”11

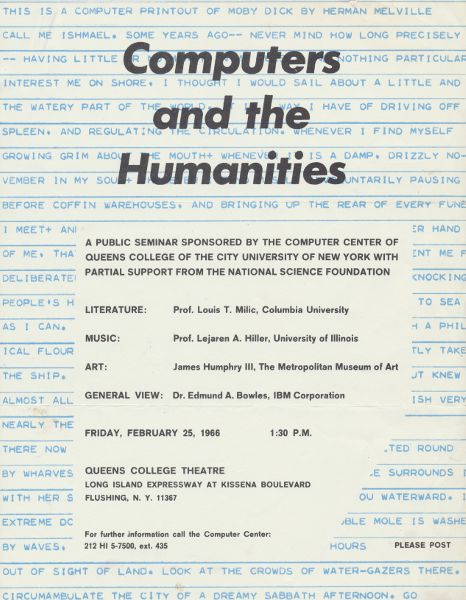

- A program for a conference titled “Computers and the Humanities” from February of 1966 that features the opening script of “Loomings” set in telefax type.

- A run of the Human Issue, a student literary and art journal that Vincent helped oversee. The Human Issue was first published in the fall of 1970 once Kent State had become a visible symbol of state-sanctioned violence, its pages saturated with mediations on the physical devastations wrought by machines both material and abstract.

- A newspaper clipping from 1975 with the headline “GM Loses Whales, Gets a Headache.” The article summarizes the failure of General Motors to conform to a 1971 law protecting sperm whales as an endangered species. In 1975 GM was ordered to recall over five hundred cars made between 1971 and 1975 that still used sperm oil in their rust-resistant transmission fluid.

- A copy of Vincent’s syllabus for English 778, a course on the works of Melville, to be taught in the Kent State summer quarter of 1970.12

Enter Captain Ahab

“Begun as a simple book,” wrote Vincent, “Moby-Dick grew into rich complexity. It is a coagulate of strange stuff” (Trying-Out, 51). Many scholars such as Vincent surmised that Herman Melville began writing a heroic adventure before August 1850, a story in the spirit of Joseph C. Hart’s Miriam Coffin (1834), William Comstock’s Life of Samuel Comstock, the Terrible Whaleman (1840), and Harry Halyard’s decidedly pulp fiction Wharton the Whale-Killer! (1848) (each is cited in the “Extracts” section of Moby-Dick). Although there is no consensus on the exact chronology of Melville’s composition of Moby-Dick, it was generally agreed upon that there was a profound shift in form as well as content after August 1850. The cause of this shift may have been Melville’s reading of Shakespeare and/or Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s theory of Shakespearean tragedy, Melville’s correspondence with Nathaniel Hawthorne, or simply his dissatisfaction with early drafts. Under the influence of something—art, culture, money, metaphysics, and so on—Moby-Dick began and ended as very different kinds of books.13

As Vincent noted in Trying-Out, “The rewriting of Moby-Dick required that sentences, paragraphs, and even chapters of the old ‘whaling voyage’ be fused with the new and larger artistic dream. Fundamental alterations were demanded: the plot must be changed, or a new one found which might better carry the various levels of communication now to be attempted; old themes had to be deepened and new ones added to communicate Melville’s awakened intellectual penetration into life.” Vincent also noted the way Captain Ahab and the “fiendish dedication of the crew to the will of Ahab” assumed prominence in the so-called final draft (Vincent, 45, 161).

Moby-Dick assumed such metonymic status as critics from across the political spectrum began to concentrate on the discrepancies between American ideals and institutional practice, with various comparisons between the United States and the dictatorships of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy emerging. On the one hand, the advent of the New Deal and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s penchant for consolidating executive powers precipitated an onslaught of totalitarian comparisons. Both business leaders and right-wing extremists like Father Charles E. Coughlin accused Roosevelt of introducing communism and fascism into the highest levels of government.14 Charges of “democratic despotism” and betrayal, however, were also common on the left as both American Communist Party leaders and journalists identified the emerging patterns “for Fascism in America.”15 Within the ranks of Melville scholarship, the patterns of totalitarianism were “discovered” and made visible in the personality and conduct of Captain Ahab.

•••

My station is pretty

I keep it in top shape

The customers dig me

’cause I got the answers

To all of their auto needs.16

Whereas in the first wave of the Melville revival, much attention was paid to Captain Ahab as tragic hero—the Byronic rebel who stormed the gates of heaven only to be denied entry, who gravitated toward “uncharted waters” with “uncompromising despair”17—in the so-called second wave interpreters increasingly noted Ahab’s “power to coerce” and “irresistible dictatorship.” As the 1930s progressed, more ominous readings of Ahab gained notice in left-leaning publications and periodicals.18

For as the 1930s progressed, the tragedy of Ahab no longer seemed heroic; rather, with the assimilation of Freudian psychology and Nietzschean existentialism into the American vernacular, it seemed a self-destructive will to power. “Melville is not Ahab,” declared Willard Thorp in 1938, but, rather, a conspiracy theorist who, in the end, conspires against his fellow man out of frustration “to know whether he is fighting against energies from the void of death which man has himself animated, or against ‘some unknown but still reasoning thing.’” Ahab, in other words, was the neurotic personality of our time, his “crime” all too emblematic of the contradictions inherent in the principle of American individualism.19 In the same year Olson accused Ahab of “solipsism which brings down a world” and viewed his crew as participating in the “citizenship of human suffering.”20

Olson, F. O. Matthiessen’s graduate student at Harvard University, would make the characterization of Ahab as a fascist more explicit in 1947 (after working with Boasian anthropologists Ruth Benedict and Clyde Kluckhohn at the Office of War Information). “Melville was no naïve democrat,” wrote Olson. “He recognized the persistence of the ‘great man’ and faced, in 1850, what we have faced in the 20th century. . . . A whaleship reminded Melville of two things: (1) democracy had not rid itself of overlords; (2) the common man, however free, leans on a leader, the leader, however dedicated, leans on a straw.”21 The totalizing forms of authority that Melville scrutinized, in other words, were mundane, murderous in their brittle emptiness.

The giddy recognition of Ahab’s totalitarianism was no doubt reflective of geopolitical anxieties at midcentury and may be traced back to the work of Melvillean and Harvard psychologist Henry Murray, who, in the 1920s, began writing a Jungian-tinged biography of Melville even as he became involved in analyzing the psychodynamics of Nazism for the U.S. government.22 In his investigation into the workings of totalitarian charisma and through his close ties to other Melville scholars, Murray’s image of Ahab evoked Adolf Hitler, Francisco Franco, and Benito Mussolini as well as “robber barons” like J. P. Morgan, media tycoons like William Randolph Hearst and Henry Luce, and radio demagogues like Coughlin and Huey Long.23

The recharacterization of Ahab from tragic hero to fascist dictator was motivated, in part, by simmering anxieties that democracy was eroding under the weight of technological innovation and that the self was no longer capable of resisting the directives of the economy. Captain Ahab had become the personification of the state among leftist intellectuals, an “unseen seer” lording over the masses. Contemporary examples of German and Italian leaders and their capacity to make a populace ignore relevant facts and embrace dangerous fictions stoked fears over media influence on the domestic front.24 Throughout the 1920s and 1930s the power and reach of radio increased exponentially and was cause for both corporate celebration and alarm among the general populace. “Radio broadcasting,” wrote Westinghouse executive Harry P. Davis in 1931, had begun “utilizing the very air we breathe, and with electricity as its vehicle entering the homes of the nation through doors and windows, no matter how tightly barred, and delivering its message audibly through the loudspeaker wherever placed.”25 Others, however, painted a more ominous picture of mass media, evoking images of “emotional possession” and “the control of opinion by significant symbols . . . by stories, rumors, reports, pictures, and other forms of social communication.”26

Such critiques were themselves allegories of antifascism that indicted not the single individual but the culture as a whole.27 The idea of the United States as a totalitarian power and/or a demiurgic force of coercion continued to gain momentum until America’s entrance into World War II, surfacing again in the late 1940s. At this time the homogenizing effects of mass culture had, in some sense, replaced more identifiable foes as the source of America’s betrayal of its own ideals. “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception” (1944), written by Frankfurt School critics Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer while in exile in the United States, analyzed the techniques of “mass deception” wielded by radio broadcasts, movies, advertisers, and their products:

The most intimate reactions of human beings have been so thoroughly reified that the idea of anything specific to themselves now persists only as an utterly abstract notion: personality scarcely signifies anything more than shining white teeth and freedom from body odor and emotions. The Triumph of Advertising in the culture industry is that consumers feel compelled to buy and use its products even though they see through them.28

Instead of physical coercion or violence, Adorno and Horkheimer pointed to the regimentation of consciousness by popular culture and the pacifying effects of mass media as de facto totalitarianism.

•••

I’m a mechanical man

2 mechanical arms

2 mechanical legs

I’m a 2 + 2 = 4 man

Me feel swell

We work well

Me want what you want.29

Many postwar interpreters framed Moby-Dick in terms of the problems and prospects of individualism amid the swirling demands of a technological surround. According to Matthiessen, Ahab’s power was, itself, Leviathanic and a matter of technological incorporation, his “pride in his purpose ris[ing] to the final terrifying pitch when he shouts to his boat crew: ‘Ye are not other men, but my arms and my legs; and so obey me.’”30 Similarly, C. L. R. James, for example, attributed to Melville a keen insight into “the relations between man and man” but also to this space beyond the human, the space “between man and his technology.”31 It was Melville’s insight that grounded James’s own political vision of facing “things, the mass of things which dominate modern life.” In cutting through the easy pieties of the self-sustaining ego, Melville had accounted for the interdependence of material conditions and spiritual aspirations, what James called the “political structure of his symbolical presentation.”32 Beginning with the premise that the self could only realize itself in and through “things”—other selves, nature, machines, and the products of the industrialized economy—Melville delineated the limits of the self inevitably bound to an environment in self-sustaining feedback loops. According to James, “the depth and accuracy” of Melville’s observation revealed “the secret of the mechanism by which political power is grasped and wielded today” (James, American Civilization, 77, 129, 76–80).

C. Wright Mills homed in on the secret of this mechanism and, in doing so, made the question of personality as it adhered to any single person potentially disposable. According to Mills, democracy was eroding under the weight of technological innovation, the very conditions of selfhood changing in light of economic directives. “Just as the working man no longer owns the machine, but is controlled by it,” wrote Mills in White Collar,

so the middle-class man no longer owns the enterprise but is controlled by it. The vices as well as the virtues of the old entrepreneur have been “transferred to the business concern.” The aggressive business types, seen by Herman Melville as greedy, crooked creatures on the edges of an expanding nineteenth-century society are replaced in twentieth-century society by white-collar managers and clerks who may be neither greedy nor aggressive as persons, but who man the machines that often operate in a “greedy and aggressive” manner. The men are cogs in a business machinery that has routinized greed and made aggression an impersonal principle of organization.33

What is so remarkable about this passage is not so much its invocation of Melville as its stark figuration of the problem of totalitarianism as more a matter of economic and technological excess than a personality trait. In his update of the Hobbesian metaphor, Mills painted an ominous picture of everyday life as one premised on a theology of incorporation. According to Mills, traditional liberalism was blind to the coercive power of the state apparatus. According to Mills, Max Weber’s “iron cage” of capitalism had morphed into the “managerial demiurge.”34 This mortal god, supplemented by “modern communications,” had become a mental prison and a form of material enslavement for managers and laborers alike.35

Such concern with the mechanistic metaphor would reach a fever pitch in the following decades as cybernetics, computers, and schemes of automation became issues of public debate. With formidable roots in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries,36 cybernetics came of age (and came to be named as a field) in the aftermath of World War II with a self-conscious scientific community (mathematicians, engineers, psychologists, artists, corporate strategists) invested in thinking through issues of feedback control, self-organization, information theory, and neural networks.37 From the end of the war to 1970 there was an exponential increase in cybernetic publications, most of which possessed a distinct missionary zeal. For there was unwavering conviction in the efficacy of approaching the world, systematically, as a system, in order to build systematically upon it—what Mills saw as the passive adoption of “Military metaphysics” after World War II.38 Mathematical formalization was extended into previously uncharted territories—business, biology, society, and mental health. As one researcher remarked in 1965, “In essence, the scientific method [of cybernetics was] an essential part of nature.”39

Cybernetics was marked by a style of thinking that strove to think at another level, more reflectively, more systematically, more meta.40 It was thinking performed in the shadow of atomic annihilation. It was thinking conducted amid the automation of the economy.41 It was thinking as if there were no essential differences between mind and matter, humans and machines.42 And lest one forget, it was thinking made possible by machines—from the stunning security directives of the Cold War, all the computers, code-breaking, and machines that scanned the horizon for enemy fighters43—to the proposition that the brain, itself, was a machine of the highest order, under which all other forces in the human world play subservient roles.44 Indeed, there is an unwavering insistence in the cybernetic archive that humans are, and have always been, hybrid entities bound up in systems beyond their purview.

Program for the conference “Computers and the Humanities,” February 1966. Courtesy of Howard P. Vincent Papers, Kent State University Libraries, Special Collections and Archives.

The Human Use of Human Beings

Moby-Dick was written during what Jacques Ellul called “an eruption of technical progress” within America, a moment when “production becomes more and more complex.” As he wrote in 1953, “The combination of machines within the same enterprise is a notable characteristic of the nineteenth century. It is impossible, in effect, to have an isolated machine. There must be adjunct machines as well as preparatory ones.” This was a moment, moreover, when the transformations of everyday life often associated with modernity began to be recognized as such, when a “crowd of human beings began to gather around the machine” even as, or more precisely, because they were fixed in ocean reveries.45

In many sectors of antebellum life the scientific management of the material world was a heady version of Providence, or more precisely, evidence of the human capacity to use machines to overcome original sin. As the U.S. commissioner of patents, Thomas Ewbank, wrote in 1849, sin was nothing less than “deviations from the principles of science.” “Man rises with the motors,” he wrote. “His growth begins with them, and only as he extends their application or adds to their number, can he increase in real stature. Nothing can compensate for their absence, for nothing valuable can he acquire but through them. Steps of a ladder resting upon earth and reaching to heaven, he is without them an earth-worm, with them almost a God. His destinies are and ever must be wound up in them.”46 By midcentury, the New Bedford whaling vessel had long been the cutting edge of industrial technology. Aboard the Pequod the spirit of industrial capitalism was quite literally in the air, despite the fact that the whaling industry was beginning to taper off and would all but collapse after 1861 (the ships became dispensable enough to be deployed as barricades during the Civil War). In Moby-Dick, the Pequod remains the pinnacle of technical application in an established market order made up of rational human actors even as its navigational systems hint at a future in which intelligence is never consummated in or commandeered by any one single actor, including the captain.

Yet it was precisely Ahab’s merging of his personality with “the all-engrossing object of hunting the White Whale” that was exemplary for the crew and that made him such a successful and sought-after captain, his madness turned into profit by “the calculating people of that prudent” isle of Nantucket.47 Ahab’s madness is not only good business but also infectious, the imperatives of the economy on shore indirectly molding the attention of his entire crew at sea. Through his “delirious but still methodical scheme,” Ahab is bent on turning the possibility of capturing the white whale into an absolute certainty (200). “To accomplish his object,” writes Ishmael, “Ahab must use tools; and of all tools used in the shadow of the moon, men are most apt to get out of order” (211–12).

In order to stave off any potential rebellion among his crew, Ahab realizes that neither intellect nor money offer sufficient protection from the “barely hinted imputation of usurpation, and the possible consequences of such a suppressed impression gaining ground” (213). Instead, he must commandeer and consume the souls of his crew. “That protection could only consist in his own predominating brain and heart and hand, backed by a heedful, closely calculating attention to every minute atmospheric influence which it was possible for his crew to be subjected to” (213).

It is the virtual presence of Moby Dick, then, and not the whale itself that allows Ahab to wield authority over the Pequod and to create “abashed glances of servile wonder” among the crew (518). “What do ye do when ye see a whale, men?” cries Ahab from the quarterdeck. “‘Sing out for him!’ was the impulsive rejoinder from a score of clubbed voices.” In focusing the crew’s calculating gaze upon the horizon, a seamless and collective identity is quite literally conjured out of the air. As the shouts among the crew grow in intensity, “the mariners began to gaze curiously at each other, as if marveling how it was that they themselves became so excited at such seemingly purposeless questions.” Ahab, then, pulls out a “Spanish ounce of gold” and rubs it “against the skirts of his jacket, as if to heighten its luster, and without using any words was meanwhile lowly humming to himself, producing a sound so strangely muffled and inarticulate that it seemed the mechanical humming of the wheels of his vitality in him” (161–62). When Ahab nails the gold doubloon to the masthead, he has further consolidated the crew’s attention through economic incentive, merging the will of the crew with his own. A well-oiled human–machine hybrid, sailing under the sign of the industrial economy. “Ye are not other men,” Ahab enjoins his crew, “but my arms and my legs; and so obey me” (568).

The World We Live In

Born in Trinidad C. L. R. James arrived in the United States from his home in London in October 1938 at the invitation of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. Planning to stay only a few months, James embarked on a series of speaking engagements across the country. He would remain in the United States until his deportation in 1953. He had just published The Black Jacobins (1938), and much of his writing, including his as yet unpublished manuscript of American Civilization, shared much of the Popular Front’s animus toward the “mighty bureaucratic centralized apparatus” and “immense accumulation of institutions and organized social forces which move with an apparently irresistible automatism” (James, American Civilization, 255, 200).

Throughout the 1940s James was intimately involved in a number of radical reform efforts, from speeches and pamphlets to the organization of striking sharecroppers in southeast Missouri.48 By 1948 James had become enough of a political threat to be served with deportation papers by the Immigration and Naturalization Service. In order to make his case public and to fund his legal defense, James began delivering public lectures on Herman Melville. It was during this period that he developed ideas that would inform both American Civilization (1950) and Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways (1953).

During his stay in the United States James became increasingly concerned not with the authoritarian personality but with “the forces making for totalitarianism in modern American life” (James, American Civilization, 38). The “fundamental social barriers” had now assumed a less visible, that is to say, less racially specific, cultural existence. After having immersed himself in the study of American history and literature, James wrote of “the obvious, the immense, the fearful mechanical power of an industrial civilization which is now advancing by incredible leaps and bringing at the same time the mechanization and destruction of human personality” (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 11).

Under the auspices of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, James was imprisoned as an “alien who has engaged or has had purpose to engage in activities ‘prejudicial to the public interest’ or subversive to the national security.”49 As James confessed, “My experiences there [on Ellis Island] have not only shaped this book, but are the most realistic commentary I could give on the validity of Melville’s ideas today” (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 125). James completed the manuscript of Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways while detained on Ellis Island pending deportation on passport violations.

In Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways James argued that in describing the conditions of production aboard the Pequod so meticulously, Melville gave insight into “the modern world—the world we live in, the world of the Ruhr, of Pittsburgh, of the back country of England. In its symbolism of men turned into devils, of an industrial civilization on fire and plunging blindly into darkness, it is the world of massed bombers, of cities in flames, of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world in which we live, the world of Ahab, which he hates and which he will organize or destroy” (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 45).

As James would conclude, Melville’s “main theme” was “how the society of free individualism would give birth to totalitarianism and be unable to defend itself against it.” Melville saw clearly how the “new individualism” unleashed by the market and aided and abetted by newfound capacities for mechanical manipulation could breed the personality of Ahab. For James, Ahab was the prototype of the “modern dictator . . . best exemplified by Adolf Hitler” whose manipulation of “things” was wholly destructive. “The passionate individualistic American temperament that Melville knew so well and saw only as a danger to the organizers of society, is now stirring in tens of millions of individuals, the masses of the people, thwarted in their daily lives, hemmed in on all sides” (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 54; American Civilization, 76–80, 129).

James noted that as the prophet of totalitarianism, Melville realized that the “world is heading for a crisis which will be a world crisis, a total crisis in every sense of that word.” Rather than praising Ishmael as the sole alternative to the totalitarian personality of Ahab, James views Ishmael as the prototype of the failed working-class revolutionary leader. “Ishmael is an intellectual Ahab,” writes James. “As Ahab is enclosed in the masoned walled-town of the exclusiveness of authority, so Ishmael is enclosed in the solitude of his social and intellectual speculation.” Yet Melville’s depiction of Ishmael’s submission to Ahab, his “analysis of why this type of young man behaves as he does is one of Melville’s greatest triumphs” (James Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 34, 37, 41, 40).

Melville depicted the everyday “heroism” on display aboard the Pequod—“the skill and the danger, the laboriousness and the physical and mental mobilization of human resources, the comradeship and the unity, the simplicity and the naturalness” (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 28). In their day-to-day tasks the crew manifested the mystical bonds of democracy that transcended both racial and national boundaries. Yet despite their nascent critique the crew was never able to cast off the yoke of Ahab’s totalitarian rule.

As James wondered, “Why didn’t the men revolt?”

According to James, “Melville took great pains to show that revolt was no answer to the question he asked.” Ishmael’s failure to rally the crew to mutiny was not a failure of Melville’s political vision. On the contrary, it must be understood in terms of the ontological lesson it provided the politically committed intellectual. “In the world which Melville saw,” wrote James,

And more particularly saw was coming, there was no place any more for . . . outpourings of the individual soul. The dissatisfied intellectual would either join the crew, with its social and practically scientific attitude to Nature, or guilt would drive him to where it drove Ishmael. Hence Melville’s totally new sense of Nature, as incessantly influencing men and shaping every aspect of their lives and characters. Nature is not a background to men’s activity or something to be conquered and used. It is part of man, at every turn physically, intellectually, and emotionally, and man is a part of it.

The political utility of Moby-Dick lay not only in its narrative of decline but in its stance toward Leviathan in the Hobbesian sense, the “mass of things” brought to the fore by industrial civilization and the social relations that ensued. For “if man does not integrate his daily life with his natural surroundings and his technical achievements, they will turn on him and destroy him.” James went so far as to suggest that Ahab’s madness was, in part, the result of becoming subject to these technological capacities of “[the] most advanced achievements in the civilized world.” Ahab becomes overwhelmed by the “weapons” that surround him even as he increasingly depends upon them to achieve his “mad” purpose (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 53, 85–86, 15).

The Radial Age

Between the 1930s and the 1960s the major tire companies in Akron, Ohio—Goodyear, Firestone, and Goodrich—did not waver in their commitment to producing bias-ply tires.50 Their downtown factories were producing nearly two-thirds of all tires in the U.S. market. The bias-ply tire had long become the standard for American automobiles because it was the standard in Akron, aka the Rubber City. But the means and geography of production, which had changed relatively little in over three decades, was about to change dramatically. In 1966 the French company Michelin contracted with Sears, Roebuck to sell radial tires. Radials lasted longer than bias-ply tires, were more fuel efficient, and significantly reduced the odds of catastrophic tire failure. In a bias-ply tire the center tread and sidewalls were independent of one another, with the body consisting of multiple piles of rubber.51

Radial tires, in contrast, were based on a design that broke a single tire into subsystems that interacted with each other (whereas bias-ply tires consisted of multiple overlapping rubber piles). A higher-level mathematics had been applied. The radial cords in the sidewall enabled the inner core to act like a spring and to bend and absorb the road. This resulted in more cushion and greater ride comfort. The rigid steel belts wrapped around the inside of the tread and reinforced the strength of the surface. Increased stability in the tread region resulted in higher mileage and longevity than in the bias-ply structure. In radials, each system worked together but was individually engineered for total optimum performance.

With the introduction of radial tires into the U.S. market, Akron plants responded in the moment and began planning for the long term. Goodyear, for example, introduced the “belted bias” tire in 1967 and promoted it as an alternative to the radial. Firestone soon followed with its own version of the belted bias tire.52 The belted bias could be produced within existing plants and was basically a bias-ply tire with a strip of fiberglass wrapped below the surface of the tread. In hindsight, the belted bias rollout gave Goodyear and Firestone executives time to adjust and time to allow existing tire-making equipment to depreciate in value before the company made a clean break from the existing bias-ply plants in Akron.53 According to Charles Jeszeck, there is little doubt that “the companies [like Goodyear and Firestone] wanted to increase productivity and ‘burn out’ obsolete, nonradial manufacturing equipment before closing the plants. . . . The objective in this case was to reduce the total costs of converting from bias-ply to radial tire production.”54

In 1971, a review in Consumer Reports put pressure on the time line for deconversion when it reported that five of the seven belted bias tires introduced in the previous years had failed high-speed and tread-life tests and were, overall, inferior to the bias-ply tires they had supposedly surpassed in quality. Soon after the report was published, GM and Ford adopted radial tires on all new cars produced at their factories. Investors begin to sell off large blocks of Akron tire company stocks. The suddenness of it all caught Goodyear and Firestone off guard.55

The Consumer Reports article, however, did not fundamentally alter the fortunes of the Akron tire manufacturers. For something was already happening with an intensity that is still difficult to measure—all those machines and bodies and hands that would turn still or disappear within a generation.56 For even before the Consumer Reports article and the sudden switch by GM and Ford to the radial standard, Akron had begun to be subject to a new kind of corporate strategy that utilized systems analysis to streamline industrial processes. Operations research emerged among military planners during World War II and soon inspired theories of organizational control in the fields of business, urban planning and corporate architecture, biology, and mental health.57 With mathematical formalization becoming the engine of prophecy, the distribution of possible futures could itself be analyzed and made subject to further calculation—to the point where the future could itself be predicted with a reasonable degree of certainty.58 By the dawn of 1972 large capital expenditures were no longer making their way to Akron and were primarily going toward the construction of radial tire plants and toward fast-tracking the conversion of bias-ply tire facilities elsewhere.59

Akron had become a data point as automated factories, programmed and robotic, could be more efficiently installed in locations outside Akron.60 The tire-making equipment in Akron could then depreciate in value at a predictable clip. For on the one hand, the traumas induced in Akron served to increase efficiency under the sign of synthetic rubber and to streamline the global tire market.61 On the other hand, the dramatic decline of the tire industry in 1970s Akron was not at all predictable. Not only were “workers, unions, and communities . . . totally unprepared for the . . . corporate initiatives against them,”62 but so too was upper management. Indeed, the data gathered in Akron factories was later deemed insufficient and unreliable. As Donald Sull has chronicled, Firestone was an object lesson in bottom-up resource allocation. Multiple breakdowns in lines of communication between factory floor and management contributed to Firestone’s failure to anticipate and adequately handle the radial restructuring.63 No one saw it coming so quickly; no one, it seemed, was in control.

As technological systems of assessment expanded, excised, and coiled, individual workers became expendable. Massive numbers of labor hours were trimmed as new automated technics were introduced in factories outside Akron as part of the transition from ply to radial tires. The twenty thousand rubber workers who lost their jobs between 1960 and 1980 may have looked for comfort to The People Side of Systems, a book published in 1976 teaching managers how to ease the concerns of workers made anxious by the incursion of computer systems into the workplace. “The secrecy of operations and centralization of administrative authority that characterize large corporations” was something to be embraced and not feared. Here was a kind of systems analysis that cared deeply about each individual—the human aspects of computer systems being recognized just long enough to be deleted from the system, which is all but equivalent to being incorporated by its system.64

The Autonomy of Technique

I got a good reason for stayin’ alive, said I

got a good reason for watchin’ my TV, said I

got a good reason for keepin’ it together, said I

got a good reason they gave to me, cause I’m

falling in love with recombo DNA, said I’m

falling in love with my corporate life form.65

Jerry Casale, cofounder of the Akron punk band Devo, drew inspiration from this automated horizon. Suffused with a “blue-collar victim aesthetic,” Akron served as “an art-directed backdrop for this kind of music we were making. . . . It had this hellish, depressing patina, this kind of dirty latex layer that fills the air.”66 Devo originated as an idea / band / conceptual art project among Kent State University students in the early 1970s. Casale, Bob Lewis, Bob Mothersbaugh, and Mark Mothersbaugh found common cause in the burgeoning underground art scene adjacent to Akron.

The impetus for Devo had begun in the wake of the shootings at Kent State. Casale, Lewis, and the Mothersbaugh brothers each witnessed the militarization of the campus in April 1970 and its senseless ending in May. May Day protests over Richard Nixon’s expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia morphed into confrontations between students and police and, by weekend’s end, the Ohio National Guard. Battles were largely over tear gas and optics as guardsmen played a perpetual game of cat and mouse with a roving protest mass.

But machines possess, if not a logic of their own, then certainly an effective politics. This is the truth of devolution and a point so obvious and so disturbing that we must cling to the conceit that we are in charge, that we are responsible, that we can make the machines stop if and when we want. But machines are built with a purpose and with the promise of an endgame defined by them. This is the nature of the tools we develop. They follow their own trajectories—gas masks or the loaded M1 Garand rifles that would eventually discharge sixty-seven bullets in thirteen seconds at 12:24 p.m., May 4, 1970.

Casale, Lewis, and Mothersbaugh each contributed regularly to the Human Issue, a student arts and literary magazine that collected the raw responses to the catastrophic violence visited on the campus.67 As Casale recalled, the Kent State shootings

completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew. . . . We were all running our asses off from these motherfuckers. It was total, utter bullshit. Live ammunition and gasmasks—none of us knew, none of us could have imagined. . . . They shot into a crowd that was running away from them! I stopped being a hippie and I started to develop the idea of devolution.68

Mark Mothersbaugh, too, saw Kent State as origin:

For a lot of reasons, the shootings gave me a focus. When I was trying to figure out what was happening in my world, I couldn’t go to school because they closed down the school for four months. I had a graduate student art space, which you weren’t allowed to have if you were only a sophomore, but I couldn’t go to it because the whole campus was shut down. So instead, Jerry would come over to my place and we would write music. That was something we could do.69

Image from the Human Issue 2, no. 3 (Spring 1971): 64. Photograph by John Sokol.

In the summer of 1972 the Los Angeles Staff had published the first Devo communiqués written by Casale and Lewis. Issued during the imminent collapse of the tire industry, these pieces were responses to immanent frames of automation and state violence. Full of absurdist puns and non sequiturs, they were also theorizations of the closures of technomodernity that drew from cybernetic metaphors of self-organization and feedback to make sense of a world that the human could not be counted on to make sense of.

Both communiqués were inspired by Ellul’s Technological Society, a text Casale and Lewis had first encountered in a class both had taken at Kent State. Their professor, Eric Mottram, had assigned Ellul’s warnings about the “autonomy of technique” as the crisis of our age. Mottram was a visiting professor of English at Kent State in the fall of ’68 (and then again in 1970–71). Mottram was a poet and essayist from King’s College London. Mottram’s reading assignments took up the “mechanization of the human sensorium” and would soon make their way into the Devo aesthetic.70

Technological Society pulled no punches when it came to its pessimistic assessment of the “‘man–machine’ complex.” Ellul, true to his French Calvinist roots, insisted on the limits of human knowledge and cast suspicions upon a world seemingly bent on setting everything in motion. He was a prophet wary of technology and the propaganda that accompanied it. According to Ellul, “The machine has created an inhuman atmosphere. The machine, so characteristic of the nineteenth century, made an abrupt entrance into a society which, from the political, institutional, and human points of view, was not made to receive it.” But to focus on the machines themselves was a critical distraction according to Ellul, for it was what the machines have cumulatively generated—“a milieu, an atmosphere, and environment, and even a model of behavior in social relations”—that served to integrate the human and the machine into ever more complex social arrangements. Ellul referred to the strange ontology of this atmosphere that had come to dominate both waking and dreaming life as “technique.” Born of human beings, technique was now independent from the human and indifferent to its future. “Technique has become autonomous,” wrote Ellul; “it has fashioned an omnivorous world which obeys its own laws and which has renounced all tradition.”71

In “Polymer Love,” Casale offered a perverse celebration of a technological society and its power to implant desire.72 In arguing that machines had already made their way in, figuratively and literally, Casale argued that our state of “polymer love” was a “closed system” because it was “predicated on the selfishness of reciprocal Suck.” Humans clung to their buffered selves even as the buffer became wholly structured by technology.73 “Ken coats his cock with a latex sheath, and Barbie swabs her sleeve with acrylic foam.” According to Casale, “the onset of techno-sexual consciousness” served both to dissolve various categorical boundaries (interior/exterior, masculine/feminine, pleasure/pain) and to resolve them in a new technical register. Humans had responded to the incursions of machines by embracing them. Riffing on Ellul—a “lubricating technique is needed which will make the machine function so smoothly that its presence is not felt. The ability to forget the machine is the ideal of technical perfection”—evoked the image of humans having mindless sex on the “read out board” of a “big UNIVAC 704.”74 To experience polymer love was to experience a powerful embrace, to become embedded within a polymerlike chain of relation that turned ever outward in strength.

Whereas Casale alluded to the dark prophecies of Ellul and his description of technique, Lewis quoted Ellul directly: “Technique does not accept the existence of rules outside itself. . . . Still less will it accept any judgment upon it. As a consequence, no matter where it penetrates, what it does is permitted, lawfully justified.” Lewis compared technique to electronic noise—a “monster boring into us at every hour of the night without respite.” Leviathan had become surround sound. In “Readers vs. Breeders” Lewis cited Ellul and his sense that machines were making their way in: “As Jacques Ellul says,” wrote Lewis, “‘He who maintains that he can escape technique is either a hypocrite or unconscious. The autonomy of technique forbids the man of today to choose his destiny. . . . It is not a kind of neutral matter, with no direction, quality, or structure. It is a power endowed with its own peculiar force.”75 Technique, in other words, was alive on its own terms, and those terms were fast becoming our own. In writing about “Technology’s technique,” Lewis pictured a world in which happiness had been optimized for each and every person, a world in which ignorance was bliss and work and leisure were seamlessly integrated by way of the machines that bound us together. “Technique,” wrote Lewis, citing Ellul, is “any complex of standardized means for attaining a predetermined result which converts spontaneous and unreflective behavior into behavior that is deliberate and rationalized and which is concerned with the immediate consequences of setting standardized devices in motion.”76

Ellul’s sentence extends outward, runs ahead of itself, suggesting that technique encompasses any potential description of it from a superior position, that it has already absorbed any potential critique. In Lewis’s and Casale’s readings of Ellul, they emphasized technique as a theological concept—signaling not the sacred, per se, but the fragility of reason and the saturation of systematic power.

In order to avoid the false religion and “horror of cybernetic man,” Lewis ended his communiqué by arguing that one must begin to appreciate the cybernetic transformation of the world. “If you find this explanation and–or presentation of the concepts of Devolutionary thought stimulating or repulsive, I suggest that you a) study carefully the essay portions of this presentation, b) contact the Devo-tees through the newspaper, and c) consult the September 1971 issue of Scientific American, volume 224, number three.” The issue to which Lewis referred was devoted to cybernetic approaches to energy, control, and information theory. The human was nowhere to be found in this issue, and perhaps that was the point from the beginning.77

For as the members of Devo came to insist, their ideas and their music would not have existed without the aid of machines. “By the process of natural selection they met and shared the habits of making electronic noise, watching T.V. and watching everybody else. They called what they saw around them De-evolution and called their music Devo. It made the sound of things falling apart.”78

Harpoon Hall Revisited

In the year following the publication of their communiqués, Casale and Lewis produced some of the first musical recordings that could be called Devo. One night in the summer of 1973 they rehearsed dirty blues in a professor’s house near Kent State campus. Casale and Lewis were house-sitting for none other than Howard Vincent. That evening they set up their amps and microphones and recording equipment in the basement, dubbed “Harpoon Hall” for Vincent’s obsessive collection: walls and bookcases full of scrimshaw and sextants, the stove rendered at once useless and a fire hazard, full of newspapers and nautical equipment. According to Lewis, Vincent’s house was a shrine to the mechanical conceits of sperm whale hunting, to the technological prowess used to hunt, capture, kill, and commodify. In the basement they recorded songs that captured the erotic submission to the technological surround, a counter to the pretensions of “masochistic theater groups and all these high brow musical groups” that claim there is something better than “kick-ass rock and roll.” For the question of technique—its strange ontology and its naturalization—remained, wrapped up in metaphors of teenage love: “I don’t know why I love you like I do / I don’t know why the sky is blue.” The spirit of the machine, atmospheric, all consuming, an agent unto itself.79

Consequently, it has been my outrageous conceit, from the beginning, that Devo and their theory of devolution must be understood as part of the reception history of Moby-Dick, at least to the degree that Vincent’s basement in the summer of 1973—full of whaling arcana and Vincent’s technological concern—is a site where the energies of both technique and Moby-Dick were intensely felt.

In Harpoon Hall, in the summer of 1973, Moby-Dick once again considers the power of technology and its human seep. Once again, Moby-Dick frames the authority of Captain Ahab in terms of a life become technicized. In Vincent’s basement, in the summer of 1973, Moby-Dick becomes a critique of the cybernetic strategy bent on achieving control beyond control. For such striving for algorithmic mastery begged the question of who or what was being controlled and by whom. Indeed, the cybernetic vision underlying postwar sciences assumed that human sovereignty was secured in the moment of its willful dissolution. For at the heart of the cybernetic dream were generative tensions that propelled it forward, particularly the tension between an all-in affirmation of the agentive capacity of the human to actualize itself, fully and wholly, and the radical negation of that subject in the moment of its incorporation into a system whose contours could not be delimited with absolute certainty.

From this perspective, Moby-Dick becomes a book taken with feedback, complexity, infinite horizons, self-regulating systems, and machine learning. It knows that the material environment is not passive. It knows that machines are not merely prosthetics of the human will. It knows that the body cannot be understood as discrete. It feels within relays and circuits of power and force that constitute it and perhaps even transcend it. From this perspective, a Devolved framing of Moby-Dick, in general, and whaling technology, in particular, is part of a longer reassessment of Ahab as a tragic hero. The source of Ahab’s “power to coerce” and “irresistible dictatorship” located by Vincent and others in the fragile and flawed human subject was, in Vincent’s basement, twenty-five years later, part of the technological surround.

In Harpoon Hall tensions were thick, between humanist pathos and posthuman surrender, between the creative agency of the human and the agency of structure, between linear history and a genealogical blur of past, present, and future. These tensions, moreover, become real only in hindsight, well after the machines had accomplished their work and proven, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that in the beginning was the end. For strangely, in Vincent’s basement, in its museum rehearsal of the nineteenth-century tools of human conquest, Devo homed in on what they had learned from Ellul—that tools of various kinds had long turned against them, teasing them, mocking them, incorporating them.

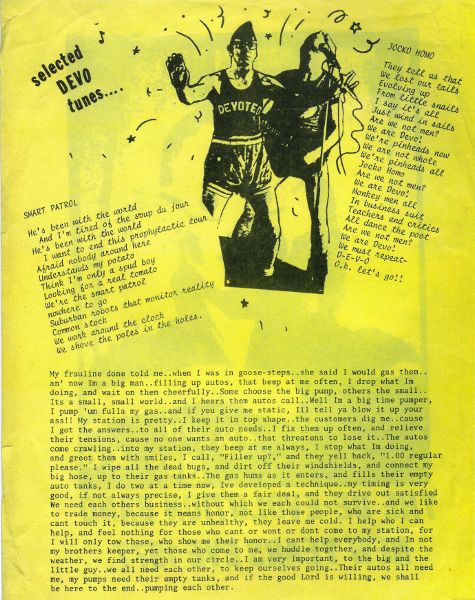

Flyer for Devo’s New Year’s Eve Show at the Crypt, December 31, 1976, with lyrics for “Smart Patrol,” “Jocko Homo,” and “Frauline” [sic]. Devo Unmasked (London: Rocket 88, 2018), 49. Courtesy of the DEVO Archives.

Ellul’s insights into the saturation of technique were dutifully repeated between the lines and notes of much of Devo’s early, angry, and perverse output throughout the 1970s. The possessive tendencies of technique were distilled in an early Devo demo from 1974. “Fraulein” conjures the ominous arc of technique in the twentieth century as it moves from the deadly efficiencies of the Final Solution to the niceties of the service economy then becoming the primary economic opportunity for laid-off tire workers. First performed at the Crypt in Akron in 1974 with a cacophonic swirl of synthetic sounds,80 “Fraulein,” written by Mark Mothersbaugh and Casale, begins with a hint of romance and a gesture toward the narrator’s origins in Nazi Germany—all a setup for his newfound alienation in the land of opportunity:

Well my fraulein done told me

When I was in goosesteps.

She said I would gas them

And now I’m a big man

Filling up autos

That beep at me often

I drop what I’m doing

And wait on them cheerfully.

The murderous edges of a previous technical application are smoothed over in 1970s Akron. As the monologue unfolds, the narrator’s labor becomes purely aesthetic and utilitarian. Or so it seems. For as the narrator describes his duties, a menacing eroticism comes to the fore as he describes his own skill, the mutual investment in automobiles, and a community mediated by the mundane machines that surround it:

I wipe all the dead bugs

And dirt off their windshield

And connect my big hose

Up to their gas tank

The gas hums as it enters

And fills up their empty tank

I do two at a time now

I’ve developed a technique

My timing is very good

If not always precise

I give them a fair deal

They drive off satisfied

We need each other’s business

Without which we could not survive.

“Fraulein” offers a perverse riff on “A Squeeze of the Hand,” Chapter 94 of Moby-Dick, which Vincent and many others have read as a “counter-theme of sociality” (Vincent, 328) to Ahab’s totalitarian regime. The physical labor of the gas station attendant becomes both productive and sexually charged as he mines the possibilities, à la Ishmael, of democratic relations with a squeeze of a metal handle. More in keeping, perhaps, with James’s reading of this scene in which “squeezing spermaceti” produces a fleeting “sensation of comradeship and fraternity” only to be incorporated by Ahab’s will (James, Mariners, Renegades, and Castaways, 44), “Fraulein” depicts the brutal efficiency of the Holocaust as it becomes repurposed at the gas station. Happy commuting and social relations, both, become matters of submission to machines and their metaphors.81 There may be no physical contact or even lasting communion, but it feels pretty good.82 In light of the autonomy of technique, one is left wondering to whom or to what an “abounding, affectionate, friendly, loving feeling” (Moby-Dick, 416) is now directed:

We huddle together

And despite the weather

We find strength in our circle

I’m very important

To the big and the little guy

We all need each other

To keep ourselves going

Their auto’s all need me

My pump’s need their empty tanks and

If the good lord is willing

We shall be here to the end

Pumping-each-other

Pumping-each-other

Pumping-each-other.

Similarly, in Moby-Dick the “frantic democracy” of the crew is consistently subsumed under the weight of the Pequod’s material order. The tools of the whale hunt become ever encompassing, their totalizing tendencies made manifest, their materiality and futurity generating “a milieu, an atmosphere, an environment, and even a model of behavior in social relations.”83 Technique flourishes aboard the Pequod. The harpoons, the charts, the sextants, the bowlines, monkey ropes, and blubber hooks determine action and belief even as they turn back upon their users and consume those who ascribe to their promise. Chapter by chapter Captain Ahab is hunted down by the tools he uses to conjure the virtual reality and, eventually, the living, breathing presence of the white whale. His imagination of the future, in other words, had become the future. Or so he glimpses when cursing the fact that machines had made their way into his very soul. In the moment Ahab exclaims, “The path to my fixed purpose is laid with iron rails, whereon my soul is grooved to run” (168), the white whale and the vengeance he seeks are no longer objects of his concern. As if they ever were.

Notes

1. Wai Chee Dimock, “A Theory of Resonance,” PMLA 112, no. 5 (October 1997): 1060. Further citations in the text.

2. Walter Benjamin, “Literary History and the Study of Literature,” in Selected Writings, vol. 2, 1927–1934, ed. Michael Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 464, 460–61.

3. Vincent quoted in Helen Cullinan, “Whales Ride Wave of Nostalgia,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 27, 1975.

4. Howard P. Vincent, The Trying-Out of “Moby-Dick” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1949). Further citations in the text.

5. See also the extensively annotated Moby-Dick, ed. Howard P. Vincent and Luther S. Mansfield (Fort Collins, Colo.: Hendricks House, 1952).

6. Olson cited in Clare L. Spark, Hunting Captain Ahab: Psychological Warfare and the Melville Revival (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2006), 305, 639n96.

7. Charles Olson, “Letter for Melville 1951,” in The Collected Poems of Charles Olson, ed. George F. Butterick (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 239.

8. Cullinan, “Whales Ride Wave of Nostalgia,” 9.

9. This draft was published as Howard P. Vincent, “Toppling the Tower of Babel,” Illinois Tech Engineer and Alumnus 9, no. 4 (May 1944): 10–12. See also Lydia Liu, The Freudian Robot: Digital Media and the Future of the Unconscious (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 130.

10. Manuel Almada, “Suicide of an Industry,” Yankee Magazine, March 1966.

11. Kenneth R. Martin, “Yankee Whaleman and the Enigma of the Avenging Whale,” Mankind 3, no. 11 (1973): 54–61.

12. I would like to thank Amanda Faehnel at Special Collections and Archives, Kent State University, for helping me navigate the papers of Howard P. Vincent. Thanks, too, to Gerald Casale and Bob Lewis for encouraging my curiosity.

13. The first appearance of the “two versions” theory was put forward by Leon Howard in the early 1940s. It was elaborated on and refined in Charles Olson, Call Me Ishmael (New York: Reynal and Hitchcock, 1947); Harrison Hayford, “Two New Letters of Herman Melville,” ELH 11, no. 1 (March 1944): 76–83; see also Hayford’s “Unnecessary Duplicates: The Key to the Writing of Moby-Dick,” in New Perspectives on Melville, ed. Faith Pullin (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1978), 128–61; see also George R. Stewart, “The Two Moby-Dicks,” American Literature 25, no. 4 (January 1954): 414–48; and James Barbour, “The Composition of Moby-Dick,” American Literature 47, no. 3 (November 1975): 343–60.

14. See, for example, the 1941 Senate testimony of Carl H. Mote, president of Northern Indiana Telephone Company, as well as Coughlin’s “The Menace of the World Court” (1935). Both are anthologized in David Brion Davis, ed., The Fear of Conspiracy: Images of Un-American Subversion from the Revolution to the Present (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1971).

15. Raoul E. Desvernine, Democratic Despotism (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1936); George Seldes, You Can’t Do That: A Survey of the Forces Attempting, in the Name of Patriotism, to Make a Desert of the Bill of Rights (New York: Modern Age Books, 1938), 207–9.

16. Devo, “Fraulein” (1974).

17. Raymond M. Weaver, Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic (New York: George H. Doran, 1921), 382, 332.

18. William Charvat, “American Romanticism and the Depression of 1837,” Science and Society 2, no. 1 (Winter 1937): 73. As early as 1932, Marxist literary critic V. F. Calverton praised Moby-Dick for its “indictment” of “our whole capitalist society” yet faulted it for its failure to provide adequate solutions. Calverton, The Liberation of American Literature (New York: Charles Scribner, 1932), 272–73.

19. Willard Thorp, Representative Selections of Herman Melville (New York: American Book, 1938), lxxxi, lxxi. On the diagnosis of neurosis, see, for example, the neo-Freudianism of Karen Horney’s widely popular The Neurotic Personality of Our Time (New York: W. W. Norton, 1937). Horney argues that the contradictions of any particular culture will be reflected in the neuroses of its inhabitants.

20. Charles Olson, “Lear and Moby-Dick,” Twice-a-Year 1 (Fall–Winter 1938): 186, 189.

21. Olson, Call Me Ishmael, 64.

22. Spark, Hunting Captain Ahab, 9.

23. As early as 1930, John Gould Fletcher had moved toward a version of Ahab as political dissimulator in The Two Frontiers: A Study in Historical Psychology (New York: Coward-McCann, 1930), 263.

24. For popular appraisals of propaganda during World War I, see Heber Blankenhorn, Adventures in Propaganda (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1919); and George Creel, How We Advertised America (New York: Harper, 1920).

25. Harry P. Davis, foreword to Frank P. Arnold, Broadcast Advertising: The Fourth Dimension (New York: John Wiley, 1931), xv.

26. The phrase “emotional possession” is used by Herbert Blumer, Movies and Conduct, quoted in W. W. Charters, Motion Pictures and Youth: A Summary (New York: Macmillan, 1934), 39; Harold Lasswell, Propaganda Technique in the World War (New York: Knopf, 1927), 9.

27. On allegories of antifascisms, see Michael Denning, The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century (London: Verso, 1996). On the relation between the Melville revival and the Popular Front, see John Lardas (Modern), “Specters of Moby-Dick: A Particular History of Cultural Metaphysics in America” (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 2003).

28. Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, “The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception,” in Dialectic of Enlightenment, trans. John Cumming (New York: Continuum, 1993), 167.

29. Devo, “Mechanical Man” (1974).

30. F. O. Matthiessen, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1941), 445, 448, 454.

31. C. L. R. James, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 2001), 54, 88. Further citations in the text.

32. C. L. R. James, American Civilization (Cambridge: Blackwell, 1993), 69, 67, 63, 79. Further citations in the text.

33. C. Wright Mills, White Collar: The American Middle Classes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), 108-9.

34. Mills, White Collar, 357.

35. Yet in Mills’s Manichaean universe, the sharp-witted sociologist and “the independent artist” remain the ones who can expose the “managerial demiurge” for what it is, rallying the masses to overcome its rule through penetrating knowledge of the machine and the self. C. Wright Mills, “The Social Role of the Intellectual,” in Power, Politics, and People: The Collected Essays of C. Wright Mills, ed. Irving Louis Horowitz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963), 299.

36. Jonathan Sheehan and Dror Wahrman, Invisible Hands: Self-Organization and the Eighteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015); James R. Beniger, The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986); Laura Otis, Networking: Communicating with Bodies and Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001); Evelyn Fox Keller, “Organisms, Machines, and Thunderstorms: A History of Self Organization, Part One,” Historical Studies and the Natural Sciences 38, no. 1 (2008): 45–75.

37. Steve Joshua Heims, The Cybernetics Group (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991); Ronald R. Kline, The Cybernetics Moment; or, Why We Call Our Age the Information Age (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015).

38. C. Wright Mills, The Power Elite (New York: Oxford University Press, 1951), 222.

39. Simulation 5 (Simulation Councils, Inc., 1965), appendix A.

40. Orit Halpern, Beautiful Data: A History of Vision and Reason since 1945 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2014).

41. Philip Mirowski, Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

42. N. Katherine Hayles, How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

43. Paul N. Edwards, The Closed World: Computers and the Politics of Discourse in Cold War America (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997); Peter Galison, “The Ontology of the Enemy: Norbert Wiener and the Cybernetic Vision,” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 1 (Autumn 1994): 228–66.

44. Edmund C. Berkeley, Giant Brains; or, Machines That Think (New York: John Wiley, 1949); Pierre de Latil, Thinking by Machine, trans. Y. M. Golla (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1957); Andrew Pickering, The Cybernetic Brain: Sketches of Another Future (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011).

45. Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, trans. John Wilkinson (New York: Vintage, 1964), 44, 112–13.

46. Thomas Ewbank, Report of the Commissioner of Patents (1849), excerpted in Antebellum American Culture: An Interpretive Anthology, ed. David Brion Davis (Lexington, Ky.: D. C. Heath, 1979), 363–65.

47. Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, ed. Harrison Hayford, Hershel Parker, and G. Thomas Tanselle (Evanston: Northwestern University Press; Chicago: Newberry Library, 1988), 186. Hereafter cited parenthetically in text.

48. Kent Worchester, C. L. R. James: A Political Biography (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 70.

49. Cited by Lisa Lowe, Immigration Acts: On Asian American Cultural Politics (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1996), 9. See also Donald E. Pease’s introduction to James, Mariners, Renegades and Castaways, xviii–xix, xxv–xxviii.

50. My understanding of the decline of this industry is drawn from many sources but is indebted to the meticulous work of Donald N. Sull. See, for example, Sull, “The Dynamics of Standing Still: Firestone Tire and Rubber and the Radial Revolution,” Business History Review 73, no. 3 (Autumn 1999): 430–64; and Sull, Richard S. Tedlow, and Richard S. Rosenbloom, “Managerial Commitments and Technological Change in the US Tire Industry,” Industrial and Corporate Change 6, no. 2 (1997): 461–500.

51. Donald N. Sull, “From Community of Innovation to Community of Inertia: The Rise and Fall of the U.S. Tire Industry,” Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, meeting abstract supplement, August 2001: L1–L6.

52. Sull, “From Community of Innovation to Community of Inertia,” 11.

53. Donald N. Sull, “No Exit: The Failure of Bottom-Up Strategic Processes and the Role of Top-Down Disinvestment,” in From Resource Allocation to Strategy, ed. Joseph L. Bower and Clark G. Gilbert (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 146.

54. Charles Jeszek, “Decline of Tire Manufacturing in Akron,” in Grand Designs: The Impact of Corporate Strategies on Workers, Unions, and Communities, ed. Charles Craypo and Bruce Nissen (Ithaca, N.Y.: ILR Press, 1993), 41. Many of the newer plants were built on land that was “twelve times less expensive than land in Akron.” J. S. Dick, “How Technological Innovations Have Affected the Tire Industry’s Structure,” part 2, Elastomerics 112, no. 10 (October 1980): 37.

55. “Tires,” Consumer Reports, August 1971, 472–77; Sull, “From Community of Innovation to Community of Inertia,” 11–12.

56. Ralph W. Frank, “Decentralization of the Akron Rubber Industry,” Ohio Journal of Science 61, no. 1 (January 1961): 39–44.

57. Sull, “Dynamics of Standing Still,” 434.

58. Judith Stein, Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

59. Technology and Its Impact on Labor in Four Industries (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1986), 6.

60. Coinciding with capital investments outside Akron was a push toward automating each of the seven steps in the tire-manufacturing process. “Micro-processor controlled instruments” were increasingly applied to the manufacturing of radials. The flexibility of computers to be reprogrammed, to control whatever functions in whatever order was necessary at the factory, in the moment, invested, among other things, much promise in the advance of an abstract “radial age.” J. S. Dick, “How Technical Innovations Have Affected the Tire Industry’s Structure,” part 4, Elastomerics 112, no. 12 (December 1980): 47–52; “Firestone Unveils Automated Tire Builder,” Rubber World, October 1968, 18.

61. Austin Coates, The Commerce in Rubber: The First 250 Years (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987).

62. Charles Craypo and Bruce Nissen, “The Impact of Corporate Strategies,” in Craypo and Nissen, Grand Designs, 226–27.

63. Sull, “No Exit,” 142–49.

64. Keith R. London, The People Side of Systems: The Human Aspect of Computer Systems (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976).

65. Devo, “Recombo DNA” (1977).

66. Gerald Casale, interviewed by the author, March 23, 2015. “Art-directed” quoted in Jade Dellinger and David Giffels, Are We Not Men? We Are Devo! (London: SAF Publishing, 2008), 21.

67. See, for example, Jerry Casale, “Number Please,” Human Issue 1, no. 1 (Fall 1970): 53; Bob Lewis, “Fat Man,” Human Issue 2, no. 3 (Spring 1971): 98–101; Mark Mothersbaugh, “decal” and Robert Lewis, “Epic Poem” and Gerald Casale, “Come Together” (cover sticker), all in Human Issue 3, no. 2 (Winter 1972).

68. Mark Frauenfelder, “Devo’s Jerry Casale on the Kent State Massacre, May 4, 1970,” boingboing (blog), May 4, 2010, https://boingboing.net/2010/05/04/devos-jerry-casale-o.html.

69. Mark Mothersbaugh, “Interview” by Adam Lerner, in Mark Mothersbaugh: Myopia, ed. Adam Lerner (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015), 33.

70. In 1972 Eric Mottram published “The Triumph of the Mobile: The Structure of Information, the Language of Computers and Contemporary Poetry,” Intrepid (Buffalo, N.Y.), nos. 23/24 (Summer/Fall 1972), edited by Allen De Loach; see also Mottram, The Triumph of the Mobile: The Structure of Information, the Language of Computers and Contemporary Poetry (London: Writers Forum, 2000). In it Mottram read through a cybernetic archive as an inspiration for experimental poetry in the vein of Moby-Dick, what he calls a “[structure] without sides or ends—Moby-Dick is an environment into which you are invited, bodily, as if into a mobile of information” (np). See also Mottram’s “Five Derivations (for Gerald Casale),” in The He Expressions (London: Aloes Books, 1973), 27–28.

71. Ellul, Technological Society, 414, 4, 100, 14.

72. Jerry Casale, “Polymer Love,” Los Angeles Staff, July 14, 1972, 36.

73. On the buffered self, see Charles Taylor, The Secular Age (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2006). On the limiting force of the buffered self as an analytic category, see my “Confused Parchments, Infinite Socialities,” The Immanent Frame (blog), March 4, 2013, http://tif.ssrc.org/2013/03/04/confused-parchments-infinite-socialities/.

74. Ellul, Technological Society, 413; Casale, “Polymer Love,” 36.

75. Bob Lewis, “Readers vs. Breeders,” Los Angeles Staff, July 14, 1972, 33; Ellul, Technological Society, 5.

76. Lewis, “Readers vs. Breeders,” 33.

77. Lewis, “Readers vs. Breeders,” 37.

78. “Tru Devo Biography,” Fan Club Ephemera, c 1981.

79. Bootleg tape of a practice from Vincent’s basement. “Devo: Whale Hall, 1973,” YouTube video, September 5, 2013, https://youtu.be/PFEVSKPCk_U.