THE MEDITERRANEAN CRISIS AND THE BACKGROUND TO THE FIRST CRUSADE

He attacked and broke into the city by force and sacked it. Large numbers were killed, even those who had taken refuge in the Aqsa mosque and Haram. He spared only those who were in the Dome of the Rock.

. . . our men entered the city, chasing the Saracens and killing them up to Solomon’s Temple . . . They killed whom they chose, and whom they chose saved alive . . . After this our men rushed round the whole city seizing gold and silver, horses and mules, and houses full of all sorts of goods.1

Both passages describe the capture of Jerusalem in the late eleventh century by foreign invaders. The first, by a thirteenth-century Arabic historian from Mosul using earlier sources, recounts the sack of Jerusalem in 1078 by Atsiz, a freelance mercenary commander of nomadic Turcomans originally from the steppes beyond the Caspian Sea. The second, from one of the earliest surviving Latin chronicle narratives of the First Crusade, celebrates the victory of the western European army at Jerusalem on 15 July 1099. The similarity between the two should give pause before assuming the uniqueness of the First Crusade. Jerusalem changed hands four times in the thirty years before the western armies’ arrival. The crusaders were relative latecomers to the violent piecemeal annexation of the cities and resources of Syria and Palestine by warlords from outside the region. The image sometimes presented of the First Crusade as a barbaric irruption into the irenic peace of a stable, sophisticated and tolerant Arab Muslim world misleads. The crusaders were just one among many bands of intruders on the make. It was precisely because the Near East was already a scene of violence, competition, disruption and dislocation that they prevailed at all.

11. The Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem.

The great Jerusalem expeditionary force of 1096–9 was made possible by simultaneous crises of political authority across western Eurasia. Over a couple of generations in the mid-eleventh century, the already ragged political map from the Atlantic to the Iranian plateau was further shredded as old and new empires were undermined, collapsed or replaced. Regional fragmentation of political authority increased competition for power. Foreign intruders proliferated: nomadic steppe Turks in western Asia; northern Christian warlords in Muslim Spain, al-Andalus; Normans in southern Italy and Sicily. Driving forces ranged from tribal searches for improved economic prospects to elite mercenary opportunism. The disruption to established political systems offered rewards to mobile groups around the Mediterranean basin: north African Berbers, Ethiopians, Nubians, Kurds, Armenians, Scandinavians, Normans and other ‘Franks’, or the tribes of the Eurasian steppes attacking or serving the armies of Greek emperors and Egyptian or Iraqi caliphs and sultans. Such dislocation prompted changes in commercial networks, demographic patterns, systems of economic exploitation and relations between established religions and civil society, from new legal emphases in Sunni Islam in the east to the assertion of ecclesiastical independence in the west. These transformations revealed strands of exchange between the three continents surrounding the Mediterranean in goods, objects, ideas, information, texts, fashions, mercenaries or slaves. Although such contacts could operate over long distances and across confessional and religious frontiers, societies in medieval Eurasia were inevitably constrained by geography and technology. For most, horizons were local; even on the vast Eurasian steppes locality was tribal. Yet the political eruptions of the eleventh century that produced the First Crusade exposed a connected world.

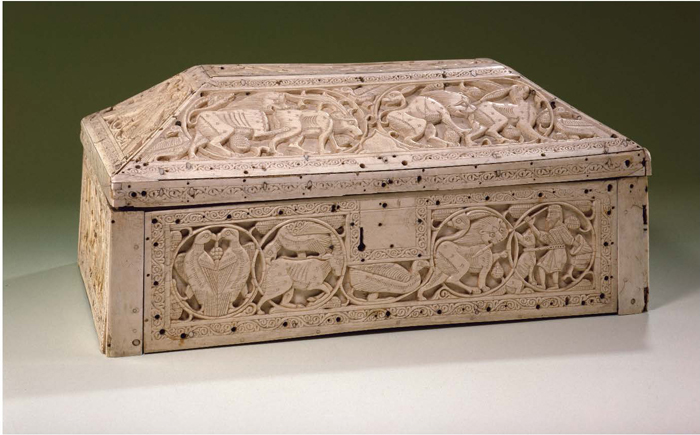

12. Cultural exchange across geographic, political and religious frontiers: an eleventh–twelfth-century central Mediterranean ivory casket.

The Fraying of Empires

In 1000 the Mediterranean was circumscribed by four empires: the Abbasids of Iraq; the Fatimids in Egypt; the Greeks of Byzantium; the Umayyads in Spain; and a fifth of more evanescent aspiration, the Germans in Italy. By 1300, the Abbasids, Fatimids and Umayyads had gone; the German role in Italy had been reduced to transience; and Byzantium only survived in severely reduced circumstances. Even at the height of their strength, each empire concealed faltering or unrealised cohesion. In largely mono-faith European Christendom power and legitimacy rested on the exploitation of mainly agrarian societies, geographically rooted in local regions and confected tribal identities (Franks, English, Saxons, Flemish, Burgundians, Danes, and so on), making ideals of pan-European political unity inherited from the Christian late Roman Empire and revived by the Frankish empire of Charlemagne (768–814) victims of material localism. Islamic polities were different. Fusing belief, law and political authority within the conceptual universalism of a frontierless Muslim community (the umma) of shared language and culture, the original Arab empire created in the seventh and eight centuries inherited and maintained a more urbanised, commercially prosperous economic system from its Romano-Byzantine and Persian predecessors. Its assertion of supra-tribal and supra-regional political legitimacy was matched by international exchange of commerce and learning. Merchants and scholars passed relatively freely across an Arabised society that stretched from the Atlantic to India. Below this internationalism, diversity of ethnicity and religious affiliation were recognised, as conversion to Islam was slow and regionally patchy. Significant Christian and Jewish communities remained. The heterogeneous culture of the Arab empire thus stood in contrast to more monochrome identities fashioned in the fragmented polities of western Europe.

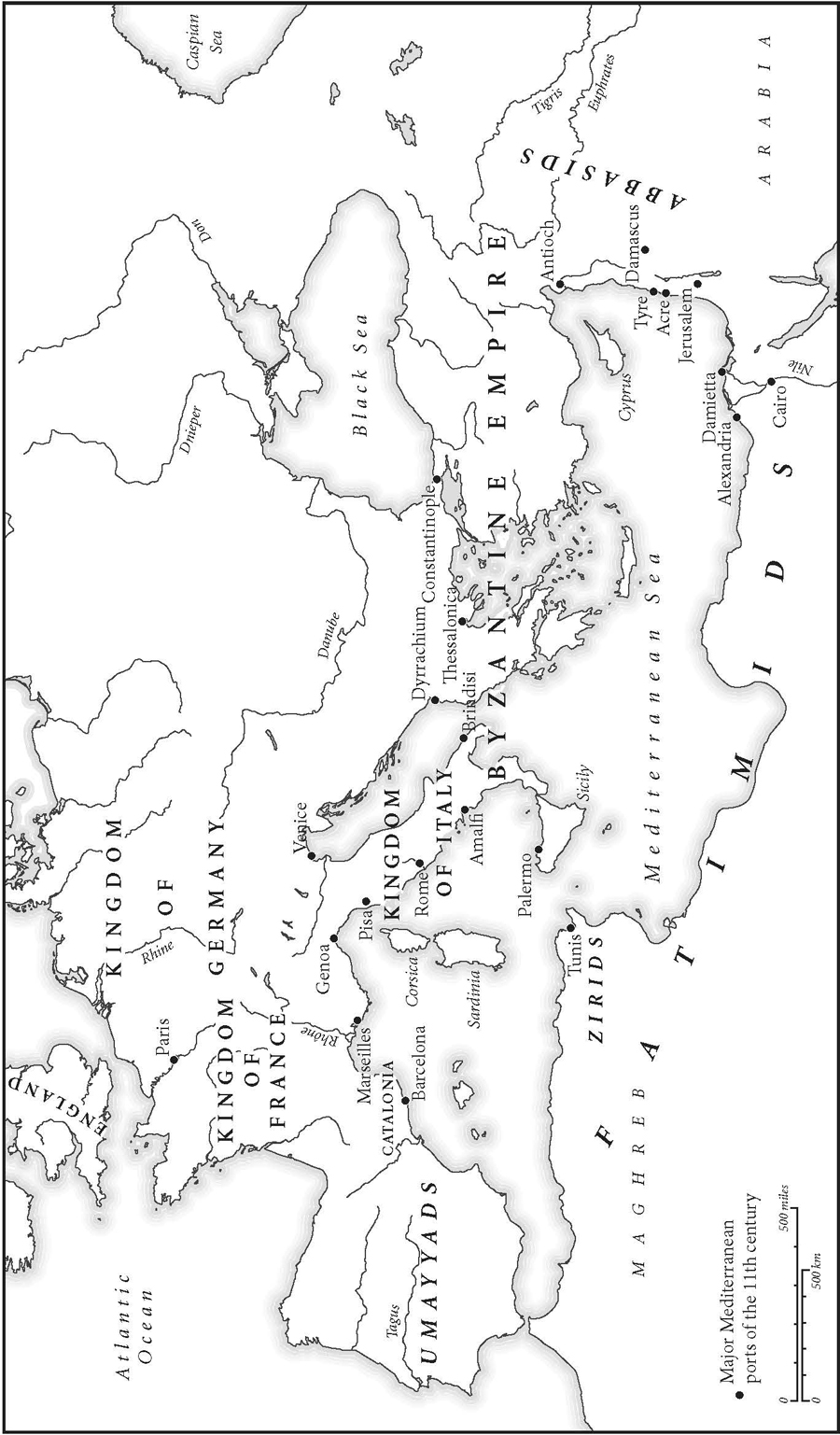

1. The Mediterranean powers in the eleventh century.

However, Islamic absence of formal separation of religious, legal and political authority invited problems of legitimacy. While the caliphate embodied the inherited authority of the Prophet within the umma, providing a focus of political legitimacy, this did not necessarily imply an active caliphal role. Beneath the caliph’s theoretical authority, local political power could emerge in a succession of regional dynasties without disrupting the perceived theoretical unity of the Islamic system even when central caliphal authority was ignored or, by 1000, rejected, as in Spain and north Africa. Given a monetised economic system reliant on a taxpaying populace, ruling elites could be mobile, dependent less on long-standing local roots than on control of cities and access to urban and rural rents in order to recruit mercenary or enslaved troops. This structure of power reflected the Arab empire’s construction in the seventh and eighth centuries. It imposed a foreign ruling elite on existing Roman and Persian fiscal structures, buttressed by Arab migration and the military harnessing of nomads, such as the Bedouin and those from the steppes on the new empire’s peripheries. The system that emerged sustained diversity of regional power within a cohesive Islamic cultural polity that stretched across two continents.2 In contrast with the divisions in Christian Europe, in the Arab sphere political rivalry and dynastic ambition played out beneath a unifying cloak of a caliphal authority that bestowed legitimacy while wielding little direct power. The common western European insistence that title to power depended on its substance, seen in the anathematising of do-nothing kings, rois fainéants, belonged to a different political universe. However, medieval Islamdom was to change during the two centuries of the Near Eastern crusader interlude with the end of the traditional caliphates and the emergence of more recognisably unitary autonomous states.

The Abbasids

In Iraq, from the 940s, the once-dominant Abbasid caliphate, established in the mid-eighth century, had been controlled by a succession of emirs from a north Iranian Shi’ite dynasty, the Buyids, who, behind formal deference to the politically emasculated Abbasid caliphs, exercised power through a family coalition of rulers across Iraq and western Iran. They relied on accommodation between their Shi’ite beliefs and those of their Sunni subjects and taxpayers, and on polyglot armies, including Turkish slave troops in a system that lacked cohesive unity. From the 1020s, nomadic tribes from the central Asiatic steppes beyond the Arab world began to migrate south and west, towards Anatolia, attracted by political instability and access to new pasture. In contrast with the Turkish troops recruited by the caliphate from the ninth century onwards, the concerted Turkish invasion from the 1040s and 1050s, led by the Seljuks, transformed the Abbasid polity.

The Fatimids

The gradual implosion of Baghdad’s central control over the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent (the region from the Persian Gulf through Mesopotamia, the Jazira and Syria to the Nile valley) was mirrored by the fates of the Abbasid’s two rival caliphates: the Fatimid Shi’ites in Egypt and the Umayyad rulers of Cordoba in al-Andalus. In 969, from their base in north Africa, the Fatimids had conquered Egypt, the economic powerhouse and commercial hub of the Levant, establishing a new administrative capital at Cairo and ruling over a population of predominantly Sunni Muslims, Coptic and Melkite (i.e. Greek) Christians. Armed with the wealth of the Nile valley, they competed with the Sunni Abbasids for dominance over the wider Islamic world. The political contest was pursued largely in Palestine and Syria, making them a frontier zone to be fought over by outside powers. However, by the early eleventh century, direct Fatimid rule over their original north African centre of power had itself broken down as nomadic Arab and Berber tribes ranged freely and local dynasties asserted themselves, such as the Zirids in Tunis, while control of Sicily veered between Zirid overlordship and warring island dynasties.

In Egypt itself, as in Baghdad, the executive authority of the caliphs, after the robust fundamentalism of Caliph al-Hakim (996–1021), devolved onto competing court factions, a process intensified after the accession as caliph in 1036 of a six-year-old child, al-Mutansir (1036–94). Beside the court and administration, Fatimid armies comprised distinct, at times competing polyglot elements – Arab, Berber, Turkish, sub-Saharan African, Armenian – providing further scope for factionalism and dissension. As political control within the caliphate swung towards military not bureaucratic leadership, competition between Turkish and African regiments intensified, the consequent instability exacerbated by the influx into Egypt of nomads and Bedouin. In the 1050s plague and disappointing levels of the Nile flood reduced tax and rent returns, sharpening competition for control of diminished resources. In the 1060s violence between factions undermined Fatimid rule in Syria and threatened the regime in Egypt before some order was restored under the military rule of the vizier Badr al-Jamali (1074–94), an ethnic Armenian who had carved out a successful career in Fatimid Syria. Power in Egypt remained fragmented. The Fatimid caliphs claimed to be heirs to messianic imams, wielding supreme authority over both faith and law, their rule legitimised directly by God, not, as in Sunni political thought, by the collective authority of the umma. This transcendent status bestowed legitimacy on whoever held actual power under them. However, except with forceful caliphs such as al-Hakim, these theoretical claims made little difference to the realities of a heterogeneous political and social system with inherent centrifugal dynamics of communities and geography.

The Iranian poet, scholar and court official Naser-e Khosraw (1004–88), in his account of his extended travels across the Near East between 1045 and 1052, provides insight into the concurrent diversity and cohesion of the Arab world. A polymath, his leaning embraced Greek as well as Arabic philosophy and his career took him from India to Egypt to Afghanistan. Remembered chiefly for his Persian poetry, Naser had once worked for the Seljuks, visited Mecca and studied Shi’ite teaching in Egypt. His observations of the territories he crossed and the people he encountered ranged from a young pupil of the great Persian philosopher Avicenna (c. 980–1037) in a town near the Caspian Sea conducting a seminar on Euclid, to a sixty-year-old Bedouin at Harran in the Jazira who insisted he neither knew nor understood the Koran. Along the way Naser observed the military defences in Levantine and Egyptian ports prompted by fears of Byzantine naval attack, but also recorded the diplomacy that allowed the Byzantine rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Everywhere he noted the international trade with Byzantium, north Africa, Spain, Sicily and Italy, especially in textiles and slaves. Naser’s picture of the Arab world of the 1040s revealed mobile civilian a well as military elites, an international community of scholarship, doctrinal diversity, urban living and lively commerce – all within a context of political upheaval and the presence of war.3

The Umayyads

Further west, similar forces of decentralisation overwhelmed the Umayyad caliphate of Cordoba. Like its eastern Mediterranean equivalents, this Sunni caliphate, formally established in 929 after 150 years of Umayyad rule in Spain, relied on a professional literate bureaucracy, the approval of local Muslim aristocracies, and a mercenary and slave army, made up chiefly of Slavs and Berbers. In 1000 the caliphate appeared at the height of its power – rich, internally peaceful, externally effective – its de facto ruler, al-Mansur (d. 1002), launching a successful raid in 997 on the great Christian shrine of Compostela in Galicia. Yet, by the 1030s, the caliphate had disintegrated. One factor was the attempt by al-Mansur’s heirs to move towards a Christian European model of uniting legitimacy and executive power by usurping the caliphate from the Umayyads. This loosened the bonds of loyalty with the local rulers, already strained by their exclusion from administrative and military patronage. Factional struggles, Umayyad pretenders and uncontrolled Berber freebooters destroyed central authority. Al-Andalus became a cockpit for competition between its Muslim princes, exploitation by Christian rulers to the north, and invasion by Moroccan religious fundamentalists from the south.4

Western Christendom

The north-western shores of the Mediterranean presented even less unity. Power resided with regional territorial princelings and rulers of small cities and emerging maritime entrepôts in Catalonia, Provence, Liguria, Lombardy, Tuscany, Campania, Apulia and the Veneto. Around 1000, the Ottonian kings of Germany, who had revived Charlemagne’s western empire in 962, seemed to be laying foundations for a new lasting imperium based on a transalpine alliance between Germany and northern and central Italy under the young charismatic Otto III (r. 983–1002). This proved evanescent, the political future of Italy resting with local lordships, such as those in Apulia and Calabria annexed by Norman adventurers from the 1040s onwards, and cities such as Genoa, Milan, Florence, Pisa, Venice and Rome. Whatever power German emperors wielded in Italy was achieved by negotiation laced with occasional invasion. They were further challenged after 1060 by political and ecclesiastical alliances constructed by belligerent Roman popes, who supported challenges to imperial rights and authority from the Elbe to the Tiber. Further east, in newly Christianised Hungary, Bohemia and Poland, the German emperor’s power to influence local rulers became attenuated. The two generations of conflicts between German emperors and popes, known as the Investiture Contest (to 1122), limited German imperial intervention into wider Mediterranean affairs. At the same time, those seeking alternative sources of legitimacy for military adventurism in the region could look to popes eager for useful political alliances.

Byzantium

By the 1020s, the largest, wealthiest and oldest Christian power, the Eastern Roman Empire of Byzantium, had experienced a half century of extensive if expensive territorial expansion. The empire’s borders stretched from northern Syria to Apulia, the Danube to Cyprus and Crete. Its diplomatic reach touched Eurasia from Russia, the steppes north of the Caspian, Scandinavia and the British Isles, to Iran and sub-Saharan Africa. In mid-century, Greek recruiting agents left coins and seals in Winchester while their emperors had paid for the rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (1036–40; see ‘The Holy Sepulchre’, p. xxiii). Like its neighbours to the east, Byzantium relied on a professional bureaucracy, a pliant aristocracy, a peaceful capital, an increasing role for polyglot mercenaries in its armies, the legitimising glue of religion, and taxpayers. Also in common with their eastern neighbours, this aggregation of support splintered as the eleventh century progressed, the tension between defence and taxation matching that between noble, military and bureaucratic factions competing for the imperial throne. Political unrest undermined administrative efficiency. From the 1040s, the once inviolate gold currency began to be debased, losing two-thirds of its value by the 1080s. In the middle of the century, plagues exacerbated economic and fiscal problems, undermining the tax base and intensifying the contest for power. Unlike in Islamdom, where inert legitimacy clung to ancient lineage while power was exercised by others, in Byzantium – as in its classical Roman predecessor – with sufficient support from the Church, army, civil service and the capital, Constantinople, might became right. Despite periods of dual monarchy between empresses and more or less pliant spouses or juvenile relatives, there could be no lasting system of empereurs fainéants. The throne passed by military coup at least three times in the eleventh century, while the empire’s territorial integrity was compromised.

Eastern Anatolia, the core province of the empire, was penetrated by Turkish nomads from the 1020s, as was northern Syria from the 1060s. Other nomadic groups, the Cumans and Pechenegs, threatened the Danube frontier. In 1071, Bari, the last Byzantine outpost in Italy, was taken by Norman forces, who then launched a series of attacks across the Adriatic on the western Balkans. In the decades after 1070, northern Syria and Armenian Cilicia were lost and most of central Anatolia overrun by more organised Turkish invaders. Although the merry-go-round of new emperors stopped in 1081 with the seizure of power by the general Alexius Comnenus, the empire was reduced to reliance on the coastal plains and ports of Asia Minor, on Greece and the Balkans. The massive loss of taxpaying subjects and lands with which to barter internal support was not matched by any commensurate lessening of the financial and military needs of defence: far from it.5

By 1100, the existing Mediterranean polities had been overtaken by internal dislocation and foreign invasion from the Eurasian steppes, northern Europe and the deserts of Arabia and north Africa. Power became more decentralised, focused on competing city states and dominated by warrior rulers with origins outside the region, who found their own attempts to rule as challenging as it had been for those they replaced. Nomadic Turks from steppes beyond the Caspian Sea now lorded it over ancient cities of Iran, Iraq, Syria and Palestine, and occupied the ancient Anatolian heartlands of the Eastern Roman Empire. Adventurers from northern France ruled in Palermo and Messina and, from 1098–9, Syrian Antioch and Jerusalem. The cities of the north African seaboard were regular victims of Arab nomads. Moroccan Berbers determined the politics of al-Andalus. Political power in Cairo was swapped between Iraqi, Armenian, Syrian and Kurdish viziers, their armies recruited from the steppes north of the Black Sea to the Sudan. Kurds found preferment from the Caspian to the Nile. Byzantine armies welcomed Slavs, Armenians, Turks, Scandinavians, Anglo-Saxons and Frenchmen. Italian merchants appeared as increasingly familiar presences in the trading posts and markets of north Africa and the Levant. In this context, the invasion of Syria and Palestine by armies from western Europe in the 1090s and their subsequent establishment of new warrior governments based on the region’s cities, while extreme, were hardly eccentric. Local Syrian observers, by the 1090s only too familiar with alien foreign conquerors and overlords, could be forgiven for initially regarding the crusaders’ invasion as yet another, if peculiarly violent and determined, foray by foreign mercenaries, hardly breaking a long and familiar line.6

A New Dispensation: Nomads, Mercenaries and Conquerors

Seljuks

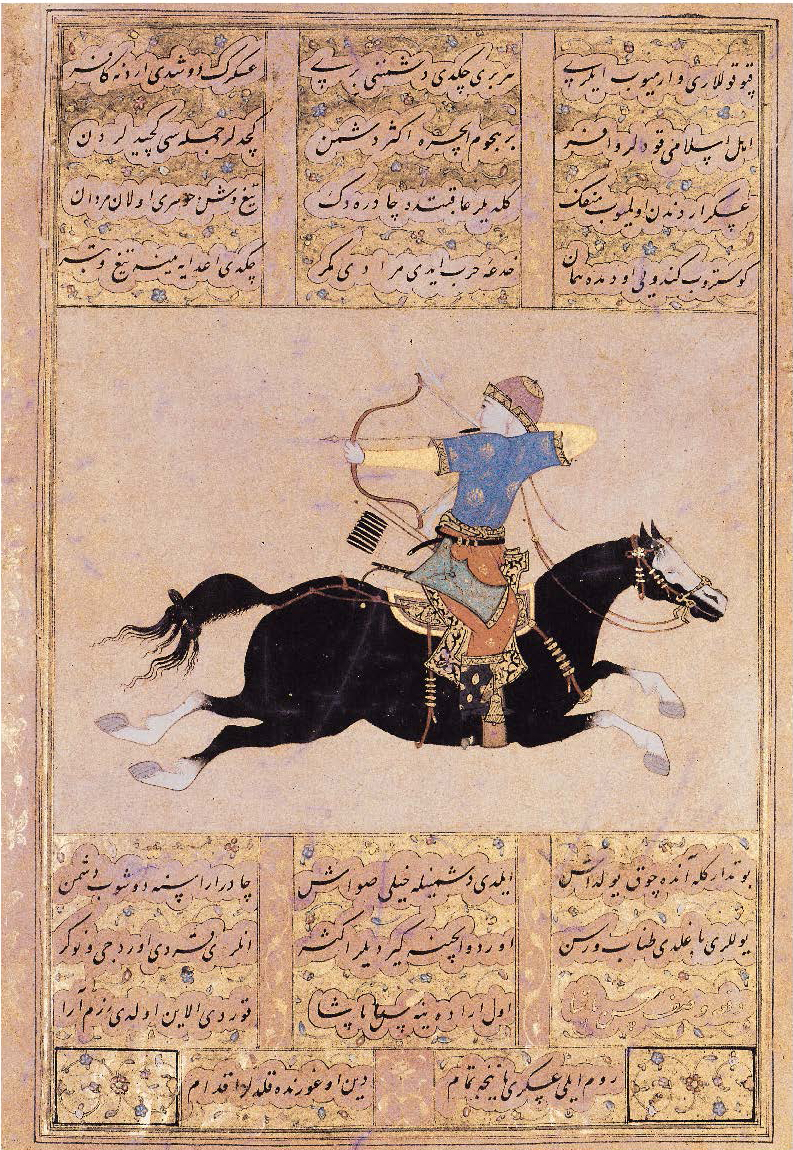

Of all the eleventh-century invaders of the Mediterranean region, the most significant were the Seljuk Turks. They reordered the Muslim world. Unlike previous usurpers of power in the caliphate, the Seljuks came from outside the old Arab empire. While steppe mercenaries and slaves had been employed throughout the caliphate for generations, the Seljuks added not just different rulers but fresh social and economic direction. Driven by pressure on resources in the steppes and attracted by long-standing economic links with surrounding sedentary societies, Turkish tribes had been infiltrating the Near East, Iran, Khoresan, Iraq and eastern Anatolia for some time before the Seljuk chieftains, leaders of the Oghuz Turks originally from the region between the Aral Sea and the Volga, moved south into Khoresan in the 1030s and to Iran in the 1040s.7 The mobile armies of mounted steppe nomads rapidly outmanoeuvred and defeated the forces of indigenous rulers, establishing Seljuk rulers in Khoresan and Iran in the 1040s, in the process forcing other Turkish nomads, often called Turcomen, to seek their fortunes further west in Armenia, northern Iraq, northern Syria and eastern Anatolia. By 1051, the western Seljuk commander, Tughril Beg, had annexed Isfahan as his capital. With north-eastern Iran in their hands, the Seljuks’ attention turned to Iraq and the fading Buyid regime in Baghdad. Unlike other nomad groups eager for a place in the sun, Tughril harboured political ambition to rule as well as to exploit.

At some point in the tenth century the Seljuks were converted to Islam. They emphasised their orthodox Sunni Islamic credentials to secure their status, in nominal loyalty to the Abbasid caliphate and in obvious contrast to the Shi’ite Buyids in Iraq and the Fatimids in Syria. In 1055, Tughril led his forces into Baghdad, sweeping aside the last Buyids and receiving from Caliph al-Qa’im the title of sultan (literally in Arabic, ‘rule’ or ‘power’), a new title for a new regime with imperial pretensions. Tughril married one of his nieces to the caliph while more significantly securing one of the caliph’s daughters for himself, an event, it was later noted, ‘as had never happened to the caliphs before’.8 These assertions of legitimacy were aided by opposition to the Shi’ite Fatimids. An Iraqi rebellion against the Seljuks attracted Fatimid patronage and support in briefly capturing Baghdad in 1058–9 before being crushed as Tughril reasserted control. The mantle of protector of orthodox Islam was to provide a convenient cloak for more than one parvenu insurgent seeking power in the Arab empire. However, despite their orthodox posturing, it is hard to cast the Seljuk invasions in religious terms. For some generations they retained aspects of steppe culture, such as burials with grave goods and the consumption of alcohol, their beliefs and rituals exhibiting an eclectic mix of steppe shamanism and adopted local Arab custom.9 Their ascendancy was achieved not by religious or cultural accommodation but by extreme violence that did not end with the creation of the sultanate in Baghdad.

Seljuk conquests, whether of Shi’ites or Sunnis, were accompanied by massacres, plunder, rapine, the payment of lavish protection money and the saturation of slave markets: after one raid in Armenia, ‘the cost of a beautiful girl came down to five dinars and there was no demand for boys at all’.10 This was not simply a matter of barbarian nomads running amok through the ancient treasure houses of Arab wealth. Soon after occupying Baghdad, the Iraqi Seljuks were employing the same polyglot mercenary and slave armies as their predecessors. However, the disruptive injection of a nomadic element into the sedentary economy and society of the Near East held lasting significance. Other nomadic Turkish tribes roamed with increasing freedom across the whole of the Fertile Crescent and Anatolia. The Seljuk Empire was run by coercion and collaboration, targeted brutality not mindless mayhem, the exploitation of urban and rural resources calibrated to secure elaborate networks of patronage and alliance.

The Seljuk system contrasted with its predecessors in ways that accidentally facilitated the later success of the crusade enterprise. Power rested with Seljuk princes who ruled the various cities and provinces of the empire as a family business, not necessarily harmoniously. Any Seljuk prince could aspire to the sultanate in Baghdad, a feature that guaranteed simultaneous cohesion and competition. The princes’ power depended on their own permanent personal military households – askars – and their paid or enslaved armies, commanded by emirs, who also recruited their own askars. Emirs and prominent askar leaders were rewarded with allocation of tax revenues from specified areas of land (iqta), or governorships of cities or regions, sometimes as atabegs, in theory guardians, mentors and military advisors to young Seljuk princes. In practice atabegs assumed independent authority, subservient in name only, a model familiar to Islamic politics. The new ruling elite was not initially territorial, princes, emirs and atabegs swapping or accumulating cities and regions according to politics and preferment not geography, a fluidity and mobility reflected in the continuing nomadic elements in the Seljuk armies.

The Seljuks and the Turks they promoted were aliens in a world of local Arab rulers and the civilian class of Arabic administrators and lawyers, notably the religious scholars, the ulema, who interpreted the law. Language presented a stubborn barrier. In the late twelfth century one Arab Syrian nobleman recalled his days fighting in the armies of Zengi, the Turkish atabeg of Mosul and Aleppo in 1135. He remembered Zengi discussing tactics with one of his commanders: ‘they were both speaking Turkish, so I did not understand what they were saying’.11 Seljuk public espousal of Sunni Islam proved important in reassuring indigenous elites and providing necessary levers of patronage and control. The great Baghdad vizier Nasim al-Mulk (d. 1092) initiated a policy of founding religious schools for the study of law and theology, madrasa. These schools provided a physical focus of Seljuk influence in buildings that became prominent features in cities from Iran to Syria; they supplied grateful members of the ulema with lucrative employment; and, in their officially directed syllabus, they helped engineer a practical accommodation between often disruptively competing Islamic legal traditions. Nevertheless, for all the techniques of soft power, the Seljuk Empire was a military system, sustained of necessity by violence. Few areas witnessed the consequences more destructively than Syria.

Syria

Greater Syria (al-Sham), including Syria and Palestine, presented a paradox in the Arab empire, at once a region of special sanctified religious significance and a frontier between the dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) and the dar al-hab (Abode of War), the front line against the infidel.12 Since the eighth century, the centre of Arab power had rested further east, in Iraq and Iran. The northern frontier with Byzantium from the Upper Euphrates to Cilicia remained porous and contested while in the 970s the Fatimids annexed much of southern Syria and Palestine. In the later tenth century, the Byzantines reconquered parts of northern Syria, including Antioch, establishing a frontier with Fatimid-controlled territory north of Levantine Tripoli. Despite occasional recourse to standard religious rhetoric, these wars hardly generated the aura of holy wars on either side. Syria remained unstable, open to attack from Iraq, Egypt and the nomadic tribes of the Syrian and Arabian deserts, divided by competition between Greeks, Armenian, and rival Arab emirs loyal to Abbasids or Fatimids and disturbed by squabbling factions within the great cities of the region – Damascus, Aleppo, Antioch, Tripoli, Edessa, Mosul. From 1064, warring Aleppans sought the help of Turkish mercenaries, who added to the embattled political scene by challenging those who had invited them in the first place.

In 1071 the Seljuk sultan, Tughril’s nephew and successor, Alp Arslan, intervened, forcing the submission of Aleppo before being called away to combat the Byzantines in Anatolia, marking the start of Syria’s integration into the Seljuk Empire. Seljuk dominance was challenged by the Fatimids in the south, by indigenous Arab elites, and by freelance Turkish and Turcoman chiefs across the whole region. In 1078 a second Seljuk invasion, led by Alp Arslan’s son Tutush, began a wholesale conquest in the name of his brother, the sultan Malik Shah (whose name symbolically combined the Arabic and Persian words for king). By 1086, Tutush had imposed Seljuk overlordship on Antioch (taken from the Byzantines), Damascus, Aleppo and Jerusalem. However, the coastal ports (Tripoli, Tyre, Acre, Jaffa, Ascalon) remained independent or nominally under Fatimid rule while the governors appointed by the Seljuks to administer the cities of the interior tended to act in their own autonomous interests, continuing regional rivalries and divisions that existed long before the arrival of the Turks. In comparison with the main centres of Seljuk power in Iran and Iraq, inland Syria lacked material and human resources, making it peripheral to Seljuk dynastic power games while forcing local rulers into fiercer competition for those limited opportunities for wealth that did exist. This combination of relative poverty and stubborn localism ensured that Seljuk power in Syria proved ephemeral. By 1115, Seljuk princes had disappeared from Syria, although the empire continued further east until the end of the century.

Division appeared early. A civil war for the sultanate after the death of Malik Shah in 1092 led to the defeat and death of Tutush in 1095. Tutush’s sons were children – Ridwan of Aleppo (d. 1113) was thirteen and Duqaq of Damascus (d. 1104) even younger. While Ridwan ruled as well as reigned, Duqaq was overshadowed by his mamluk atabeg, Tughtakin, who ultimately succeeded him in Damascus. By the winter of 1097, when the crusaders arrived before Antioch, northern Syria had fragmented into feuds between Ridwan and Duqaq and the governor of Antioch, Yaghi-Siyan, against the atabeg of Mosul, Kerboga, while further south Jerusalem was held in the name of the Seljuks by a Turkish governor until the city was captured by the Fatimids in 1098. The failure of Seljuk control in Syria proved almost unimaginably propitious for the crusaders.

Byzantine Crisis

The Seljuks were not alone in finding imperial power precarious. When he abandoned his invasion of Syria in 1071, Alp Arslan had marched to confront a Byzantine army under Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes (1068–71) advancing from Anatolia into Armenia. The subsequent Seljuk victory at the battle of Manzikert near Lake Van confirmed that there would be no effective halt to continuing Turkish penetration of the Greek Empire’s eastern provinces. However, the Turks presented only one threat to Greek imperial power. One of Romanus IV’s unreliable allies at Manzikert, the Norman mercenary captain Roussel of Balleul, set himself up as an independent lord in Anatolia. Balleul and other western-hired swords proved a mixed blessing for Byzantium, adding to the complexity of private enterprise opportunism that characterised both sides of the struggle with the Seljuks. After 1071, Turkish infiltration of Armenia and Anatolia gathered pace. In 1077 a Seljuk cousin of Alp Arslan, Suleiman ibn Kutulmush, established a sultanate based on Konya, called the sultanate of Rum. In 1078, Nicaea, less than a hundred miles from Constantinople, fell to him. Soon most of the hinterland of Asia Minor and parts of the Aegean coast were in the hands of various Turkish warlords and pirates, threatening supply lines to the Byzantine capital. Across the former eastern provinces, Turcic tribes, including a nomadic group known as Danishmends, preyed on towns and settled agriculture more or less at will. In the west, the loss of Bari in 1071 to Norman freebooters led by Robert Guiscard was followed by Norman campaigns along the eastern Adriatic coast around Dyrrachium in 1081 and 1085. In the northern Balkans the Pechenegs, a coalition of steppe tribes from beyond the Danube, had penetrated the empire’s frontiers. After their defeat in 1091, another group of nomads, the Cumans, menaced the region. Closer to the throne, the loyalty of army high command proved unreliable.

Although Alexius I (1081–1118) managed to stabilise the Balkans in the 1080s and 1090s, this hardly inhibited the threat from Nicaea or in the Aegean. The losses of Bari and, later, Antioch (1084/5) were not reversed. Diminishing territory, especially in Anatolia, created manpower and fiscal problems: fewer taxpayers and recruits without any diminution of military needs or expense. Increasingly, Byzantium recruited troops from neighbours and former enemies, including Normans and Turks, but also western and northern Europeans, such as the Varangian Guard of Scandinavians and Anglo-Saxons. Self-interest dictated the establishment of Italian trading posts in Constantinople. In 1082, Alexius granted Venice tax exemption and free access to trade and ports within the empire in return for their assistance against the Normans in the Adriatic. Constantinople had long been a truly cosmopolitan city, attracting residents from across Eurasia from the Atlantic to the steppes. In the strategic crisis facing Alexius I in the 1090s, of particular interest were mercenaries from western Europe. It was his good fortune that a ready supply became available, although not exactly in the guise he may have expected. Like the rulers in the Arab empires who summoned steppe nomads to serve in their armies, Alexius found the westerners who answered his call had ambitions of their own.

The Rise of Western Europe

Superficially, western Europe had little to offer its eastern neighbours. Its rural economy precluded monetised systems of regular taxation. In the eleventh century, rents and renders from land were still received largely in kind not cash. In Byzantium and the lands of the former Arab empire, a commercial system was supported by gold as well as silver-based currencies and large towns and cities. In western Europe, the availability of coin, minted from various silver alloys, was limited; labour was cheaper than to the south and east, so labourers had less disposable income; cities were of negligible size. In the early eleventh century, the populations of Baghdad and Cairo may have numbered around half a million; Constantinople perhaps 600,000; Cordoba at least 100,000. By contrast, the largest western European cities, Cologne, Florence, Milan, Rome, Venice, may have harboured 30,000–40,000. By the end of the century, London and Paris may have contained about 20,000 each, hardly even third-rate by Near Eastern terms. While the quickening of economic activity, an increase in long-distance trade, a growth in markets and political centralisation greatly expanded urban populations across western Europe over the next two centuries, even cities such as Paris, which by 1300 approached a size of 100,000, were still dwarfed by the great emporia of the Near East.

The Byzantine perspective on the crusades was wholly different from that of western Christendom. In the historical context and world view of the surviving Eastern Roman Empire, the crusades formed one episode in a centuries-long sequence of disruptive incursions, distinctive as much in retrospect as in reality. Although periodically significant and finally transformative in Byzantine imperial politics, the crusades simply did not matter as much to the Greeks as they did in western Europe. The crusaders and their settlements competed for Byzantine attention with Bulgars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Serbs, Armenians, Italians, Arabs and Turks as disparate clients, subjects, rivals or neighbours within the wide Byzantine sphere of influence that stretched from the Adriatic and Danube to Cilicia and northern Syria, from the Russian steppes to the Levant. The crusades deepened and expanded ties between Byzantium and western Europe but did not initiate them. Assumptions of inevitable entrenched wariness and hostility between Byzantium and crusaders or the Franks of Outremer ignore constant economic, commercial, diplomatic, cultural and political exchange, a diversity of relationships variously marked by competition, cooperation, exploitation and co-existence. Byzantium itself covered widely disparate societies, demographics and geography. Trade between Byzantium and western and northern Europe in silks, soldiers, pilgrims, saints, slaves, metals, furs, spices or icons operated on their own separate lines, many of them long-standing by the late eleventh century. Foreign paid troops had long been a feature of Byzantine armies, for example the Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon Varangian Guard, while the mid- and later eleventh century saw an increase in western European recruits and settlers – the so-called frangopouloi – whose style of cavalry warfare was admired. The Greek call for western aid in 1095 rested on an established tradition. However, western troops were not alone; foreign recruits included Slavs, Armenians and Turks. The Byzantine polity was cosmopolitan in nature and international in reach, not least in what might be called soft power: culture, language, religion. Greek ecclesiastical and political presence in Italy and Sicily was not extinguished by the loss of the last territorial holding of Bari to the Normans in 1071. Bohemund of Taranto may have proved belligerently hostile, but he held a Greek birth name (Mark) and may well have spoken Greek.13

14. The walls of Constantinople.

Byzantine rulers assessed the crusades in customary terms of geopolitical advantage. The absence of overt ideological support grated on western observers, but Greek Orthodoxy, while traditionally embracing the idea of war in defence of religion, never embraced the western idea of penitential warfare. The failure of Greek rulers to provide crusaders with more substantial material and military aid in 1147 or 1189 fuelled suspicion and resentment. This provoked Henry VI of Germany’s bullying in 1195–6, when he demanded money with menace from Byzantium for his crusade, and encouraged the leaders of the Fourth Crusade to accept the future Alexius IV’s fanciful offer of lavish assistance in 1203. The overriding primacy of Byzantine strategic interests, which embraced alliance with Turks when expedient, and diplomatic habits including necessary deceit, offended some western observers. Consequently relations could be constructive when interests coincided, as when the Byzantines tried brokering an anti-Seljuk alliance between the crusaders and the Egyptian Fatimids in 1097–9, but they could also be fraught when they did not, as over the status of Antioch after its capture by the First Crusade in 1098. Even there, ultimately long-term Byzantine objectives were peacefully achieved with acceptance of Byzantine overlordship in 1137, 1145 and 1159. Despite tensions over Antioch, Byzantine aid assisted Frankish leaders such as Raymond of Toulouse and the 1101 crusade. Relations with Outremer Franks were pragmatically friendly, producing in the mid-twelfth century a series of marriage alliances with Antioch, Tripoli and Jerusalem, close diplomatic agreement with Jerusalem in the 1170s and joint campaigns against Ayyubid Egypt executed (1169) or planned (1177). In 1176, Manuel I and Pope Alexander III even floated a scheme for a joint crusade.

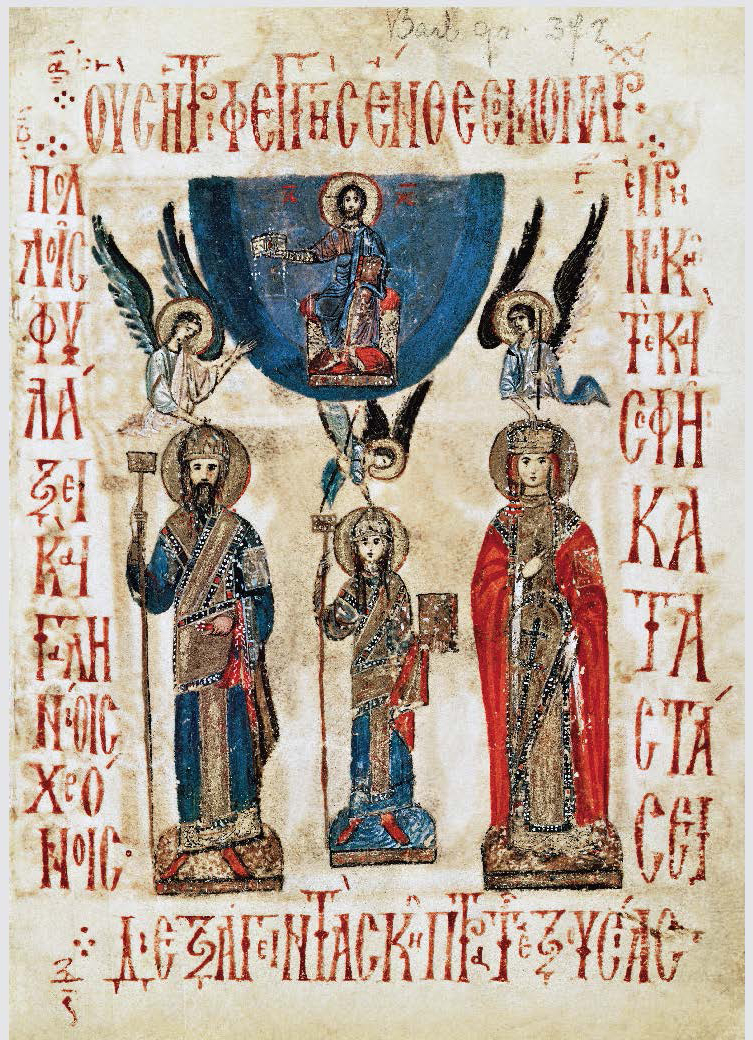

15. Alexius I, Empress Irene and the future John II.

The context of the crusades was of ever closer connections with Byzantium. Despite theological and institutional divisions between the eastern and western Churches that had prompted a public schism in 1054, Greek emperors maintained regular diplomatic correspondence with popes: between 1198 and 1202, during preparations for the Fourth Crusade, Innocent III and Alexius III exchanged at least eight embassies and twelve extensive letters. Manuel I was famously sympathetic to western influences at court, marrying an Outremer Frank in 1161, one of numerous dynastic alliances linking Byzantium to the nobility of the west. Westerners became entangled in Byzantine politics: members of the north Italian Montferrat family were closely involved in bloody coups in 1182 and 1187 as well as, more famously, 1203–4. Byzantium appeared to some a land of opportunity long before 1204. Less dramatically, Greek clergy worked in tandem with Roman Catholics in Outremer, Sicily and Calabria, as they were to do after 1191 in Cyprus. Trade provided the staple contact, fostered by the mutually profitable commercial privileges agreed with western shippers, notably the Venetians. Venetian raids in 1122–3 and anti-western riots in Constantinople in 1171 and 1182 did not inflict lasting damage; in 1198 a treaty restored all Venice’s trading rights, commerce with Byzantium comprising up to half the city’s commercial activity. Crusading quickened cultural exchange, like the western dissemination of Greek texts and translations from centres like Antioch or from shared artistic projects elsewhere in Outremer, as in the decoration of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem (c. 1170), jointly sponsored by Baldwin III and Manuel I. The flow of Greek art, relics, icons and texts increased hugely after 1204, but it had begun earlier.

16. Byzantine-Frankish cooperation: the mosaic of Jesus on Palm Sunday in the Church of the Nativity, Bethlehem.

The chief source of conflict came from immediate political crises not existential cultural alienation. For two centuries from the late eleventh century the rulers of Sicily – Normans (1060s–1194), Hohenstaufen (1194–1266) and Angevins (1266–82) – had contested Byzantine power in the central Mediterranean, usually without association with the crusades (Bohemund’s 1107–8 Balkan campaign and the threats during the Second Crusade and by Henry VI in the 1190s being exceptions). Whatever the subsequent political or literary gloss, on each twelfth-century large-scale land crusade issues of supply, not culture or religion, provoked armed confrontation, as they did again in 1204. One of the ironies of the Fourth Crusade rests in the evidence of desired cooperation not confrontation displayed in the treaties with Alexius IV. After the debacle of 1204, except for lacklustre attempts from the 1230s to shore up the Latin empire of Constantinople (1204–61) and, later, other westerner-held enclaves in Greece, crusading more often sought to include an alliance with Byzantium against mutual opponents, notably from the fourteenth century the Ottomans. However, the westerners’ price of such an alliance, union of the Greek Orthodox with the Roman Catholic Church, was impossible for successive Greek emperors, wielding much reduced religious and political authority, to deliver. In 1204 a cultural legacy of mistrust and hostility was created among Byzantines that had not existed so virulently before. The unions agreed in 1274 and 1439, as well as a plan in 1355, came to nothing. Nonetheless, a few western anti-Turkish naval leagues in the fourteenth century included Byzantium, now little more than a city state, hardly a major regional still less world power. In the last sixty years before the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453, crusades were planned and deployed to save not defeat Byzantium. As in the 1090s, Byzantium in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries was regarded as a potential, if awkward, crusading ally not enemy.14

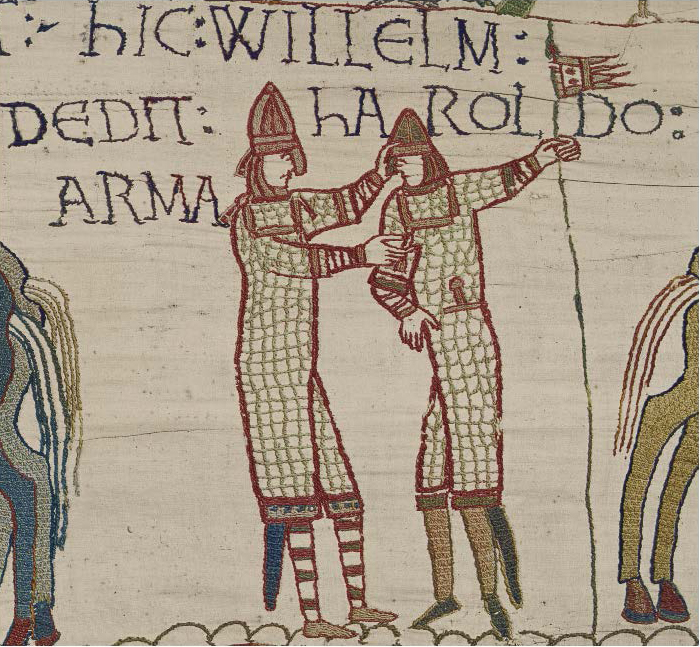

However, unlike the Near East, where climate change caused droughts, western Europe benefited from the climatic warming of the period. Agricultural yields improved; populations grew; commerce expanded; the need and use of markets and money grew. With it came social changes: modest urbanisation; enhanced levels of numeracy and literacy; and greater wealth for the aristocratic military elites who exploited these increasingly lucrative agricultural and commercial resources. The growth of towns stimulated inter-regional and international transmission of goods, people and ideas as well as the creation of newly prosperous, mobile groups of merchants and artisans. However, power remained largely concentrated in the hands of those who controlled land and the people who worked it. Political fragmentation from the late ninth and tenth centuries encouraged local lords to assert largely autonomous power, improving agricultural and commercial revenues and the consequent ability to employ military entourages to impose their authority, allowing them to sustain their independence. Castles provided visible signs of how increased wealth consolidated lordship power. Capricious rule and unbridled violence were tempered by traditional law, custom, accepted communal processes of arbitration and conflict resolution necessary within intimate social and economic communities. Competition for control of economic exploitation was fierce, pursued by technologically more sophisticated elites of armed mounted warriors. These arms-bearers, of whatever social origins, gradually developed into a distinct community of shared function, behaviour, social importance and cultural values: the knights so vividly illustrated in the Bayeux Tapestry. By 1100, a knight was synonymous with power and, as even kings depicted themselves as armed mounted warriors on their seals, symbolised authority: all nobles were knights; by 1200, all knights were noble.15

17. William of Normandy giving arms to Harold of Wessex as a sign of honour.

The competitive dynamics of lords, landed knights and paid armed retainers stimulated aristocratic social and geographic mobility. The landed warrior classes were not farmers; like their Near Eastern counterparts, they were rentiers although, unlike Turkish emirs, western lords’ legitimacy remained tied, rooted in specific localities, by ancestry, adoption, appointment or acquisition. However, a lord could exercise lordship wherever he possessed retinues and income. While this usually imposed geographic limits, in a social context where enhanced profit, status and power could be gained by force or patronage, territorial constraints could give way to more distant career opportunities, whether in a neighbouring valley, province, kingdom or beyond: for German Saxon nobles, across the Elbe into the lands of Slavs and Balts; for French lords, into Spain to fight the Moors of al-Andalus or across the English Channel; for Norman knights, over the Alps into southern Italy, Sicily and Byzantium. The availability and capabilities of western knights joined with opportunity in the Near East and crisis in Byzantium to make the First Crusade possible. It also explains why Alexius I asked for their help in 1095.

Continental Exchange

This conjunction was not random. The image of the First Crusade devised by contemporary Latin sources emphasised its unexpected uniqueness, a divinely inspired irruption of the west into the east. Much of this involved deliberate mythologising. The leaders of the western armies that set off in 1096 knew where they were going and how to get there. The caustic monastic observer Guibert of Nogent’s sneering commentary on the peasant children who set out with their parents only to ask at each town they came to whether it was Jerusalem only works as the comic insult it was intended to be if it was assumed Guibert’s preferred elite knew better.16 The speed with which a sequence of large armies reached the agreed rendezvous of Constantinople in 1096–7 alone indicates cooperation with the Greeks and prior understanding of the eastward routes, knowledge available from pilgrims, diplomats, adventurers, mercenaries, merchants and exiles. At least one leader, Peter the Hermit, had been to Jerusalem, as had the father of another, Count Robert II of Flanders. The south Italian Norman commander Bohemund had intimate experience of fighting the Byzantines in the west Balkans in the 1080s. Other crusaders, such as Guibert of Nogent’s childhood friend Matthew, from the Beauvaisis, had seen service with Alexius I in the years before the First Crusade.17 The Latin narrative sources’ almost total avoidance of Alexius’s request for military aid in 1095 tells its own story. Even if not deliberate suppression, ignoring the Greek invitation elevated the role of the pope and gilded the autonomous agency of the faithful of western Christendom. Yet paradoxically these same sources reveal how the grand interpretation of a campaign into terra incognita misleads.

On 7 June 1099 the armies of the First Crusade finally reached Jerusalem after, for most of them, almost three years on the road. That evening Duke Robert of Normandy, camped outside the Damascus Gate, received an unexpected visitor, Hugh Bunel, a fellow Norman and notorious celebrity murderer. Twenty-two years earlier, Hugh had decapitated Mabel of Bellême at her castle of Bures, ‘where she was relaxing in bed after a bath’. Fleeing Mabel’s sons, William the Conqueror’s agents, and bounty-hunters, Hugh had lived among Muslims for twenty years.18 Hugh was far from the only expatriate westerner the crusaders encountered. In Constantinople in the winter of 1096–7 they found settled western communities, the frangopouloi – ‘the Frankish people’. By the 1090s, these included Hungarians, Germans, Danes, Anglo-Saxons, Swedes, Venetians and Amalfitans as well as Frenchmen and south Italian Normans who had thrown in their lot with the Greeks after being defeated in the Balkans in 1085. Some joined the crusaders for the march across Asia Minor in 1097. Frangopouloi were not the only familiar faces in the east. When Bohemund’s nephew Tancred arrived at Adana in Cilicia in late September 1097 he may have been met by a Burgundian adventurer called Welf. More certainly, in the same month, another crusade leader Baldwin of Boulogne was joined at Tarsus by a privateer fleet of Flemings, Antwerpers and Frisians who, it was alleged, had been plying their piratical trade for eight years under the command of a certain Winemar, a former member of the Boulogne comital household. Winemar’s flotilla later seized the port of Latakia during the crusaders’ siege of Antioch.19 Whether these pirates had followed the crusade east, as other western fleets did, or had been preying on Mediterranean shipping before the crusade set out, is unknown. However, their presence and that of other convoys from the North Sea and Italy suggests that the Levant was far from inaccessible to western shipping by the 1090s.

Another feature of the crusaders’ progress towards Palestine was revealed by their adaptability to Near Eastern politics and diplomacy. The Byzantine alliance provided the catalyst for negotiations with the Fatimids, spread over nearly two years before finally breaking down a few weeks before the assault on Jerusalem.20 Surviving crusaders’ letters and early narratives suggest they quickly grasped the divided circumstances of the Seljuk princes and how they had terrorised the indigenous peoples of the region. The crusaders could call upon Byzantine diplomats and their own interpreters who knew Arabic, probably from southern Italy (see ‘Interpreters’, p. 58).21 Bohemund himself probably spoke Greek, useful as it was also spoken by many Antiochenes and others in northern Syria. Close contacts with Armenians were forged by Tancred of Lecce and Baldwin of Boulogne during campaigns into Cilicia in the autumn of 1097. Baldwin soon after found himself ruling the Armenian city of Edessa beyond the Euphrates. Armenian sources reflect an initial welcome for co-religionists. A Provençal clerk appeared alert to relative eastern and western currency exchange rates in Syria in 1099.22 None of this is surprising, as it continues the tradition of contact and exchange between western Europe, Byzantium and, more remotely, the Arab world. The story of Peter the Hermit, the outraged Jerusalem pilgrim who in some accounts sparked the whole enterprise, epitomised the threads of contact, the movement of people and goods.

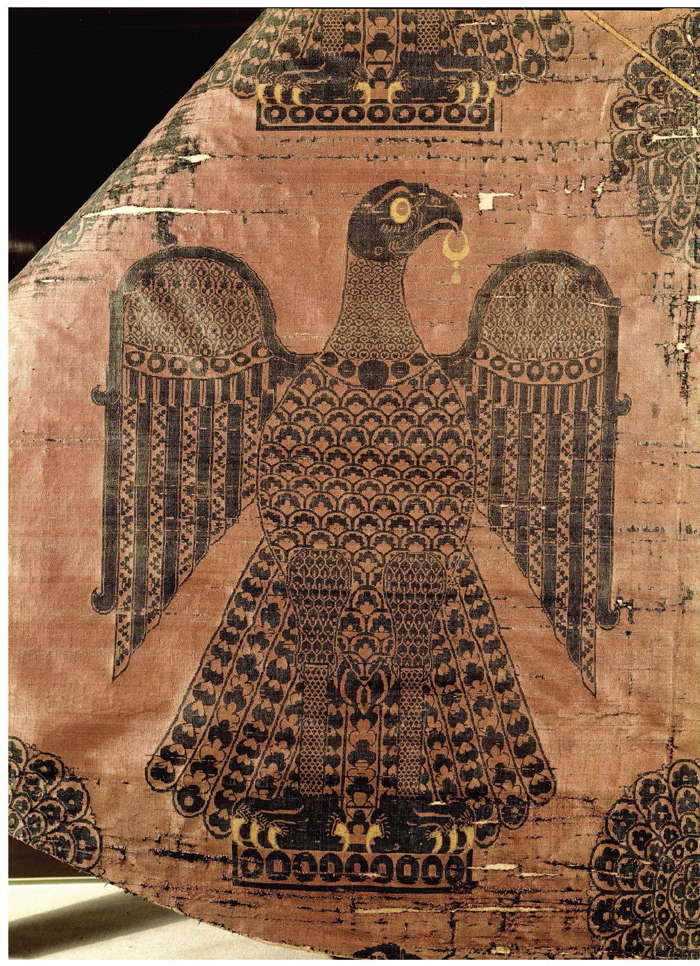

The most apparent human links were elite exchanges. The chief agent was Byzantium, the commodity military service. Scandinavians and Russians had been in imperial service for generations, joined by the 1080s by Germans and Anglo-Saxons. From the 1040s and 1050s, recruits were actively sought from England and Normandy. From the 1030s and 1040s, companies of Normans from southern Italy, valued as heavy cavalry, were regularly hired to supplement Byzantine troops defending frontiers in the Balkans and eastern Asia Minor. Their commanders often secured imperial titles, grants of lands and political influence. From the 1070s, Norman regiments appeared in imperial service under Byzantine rather than their own command. Turks were also recruited, like the polo-playing Tatikios, son of a prisoner of war, who later accompanied the First Crusade to Antioch, having previously commanded a regiment against the Pechenegs in the Balkans in the 1080s.23 Good relations with the German emperor in the 1080s had produced German contingents. After 1089 a rapprochement with the papacy under Pope Urban II opened other opportunities. In 1090, Count Robert I of Flanders, a Jerusalem pilgrim a few years earlier, sent 500 troops to defend strategic areas of Asia Minor against the Turks. By the 1090s, western clergy, including Englishmen, were permanently settled in Constantinople.24 Until the early 1070s, Byzantium had been a territorial Italian power. In the 1040s it was sending expeditions to contest rule over Sicily (and recruiting Normans to help), while Italy was still viewed from Constantinople as within its sphere of interest and influence. Southern Italy and Sicily retained significant communities of Greek speakers and Orthodox Christians. Greek emperors continued close, if sporadically fraught, correspondence with the papacy and other Italian leaders, such as the abbot of Monte Cassino. Italian commercial cities established trading posts and workshops in Constantinople, and beyond. Silk, manufactured or shipped through Byzantium, was widely sought after in western Europe. The regular commerce of people produced an eleventh-century northern French Latin–-Greek phrase list for such useful things as asking for food, drink, clothes, beds and transport.25

Byzantium stood at one corner in a much larger trading area that was transformed during the eleventh century, with the First Crusade as much a symptom as a cause. In 1000 the carriers of long-distance trade in the Mediterranean had chiefly been Muslim and Jewish shippers, working out of ports in Egypt, north Africa and Muslim Sicily: ‘not a single Christian boat floated on it’.26 By the 1090s, Italian merchants and Italian shipping had intruded and begun to dominate, especially Genoese, Pisans and Amalfitans, with Venice assuming a controlling interest in Greek waters. In part the reasons for this were political. The great fourteenth-century Tunisian historian and historiographer Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) argued that Christian conquests around the Mediterranean, combined with the decline of the Umayyads in al-Andalus and of the Fatimid Empire, had undermined Muslim investment and interest in sea power. This can be traced to the Genoese and Pisan naval competition with Muslim pirates over Sardinia in 1015/16 or the Pisan raid on Palermo in 1063, as well as the Norman conquest of Sicily (1060–91). Trans-Mediterranean commerce developed in parallel with the political disruption.27 The weakening of Byzantium, the disintegration of the Fatimid Empire in north Africa and the Norman conquest of Sicily damaged traditional trading networks, presenting fresh opportunities for western, particularly Italian merchants already embedded in international trade in slaves, gold and textiles, carried in the early part of the eleventh century mainly on Muslim and Jewish ships. Amalfitan merchants founded a pilgrims’ hospital in Jerusalem in the 1070s. Muslim commercial communities were settled in west Italian ports such as Naples, whose linen was probably exported in quantity to north Africa. Cheaper labour costs encouraged these exports to high wage economies of the Maghreb: Amalfi even shared a currency with Muslim Sicily and north Africa.

The inevitable obstacles of language that confronted crusaders as they moved east, south and north out of western Europe were novel only in degree. Many regions in medieval Europe and the Mediterranean were linguistically heterogeneous. The unifying languages of religion, learning, law and government such as Latin, Greek or Arabic concealed extremes of divergent local dialects and different tongues, such as northern and southern French or High and Low German. French-speaking elites ruled English speakers in England, Flemish speakers in Flanders, Italian, Greek and Arabic speakers in Italy and Sicily, just as Germans increasingly ruled over Slavs and Balts. Turkish lords in the Near East ruled subjects speaking or worshipping in Arabic, Greek, Armenian, Syriac and Hebrew. Byzantine Greeks employed speakers of French, English, Latin, Turkish, Norse and Slavic. Politics, diplomacy, government, administration, commerce, even law relied widely on translation, multi-lingualism and, thus, interpreters.

For crusaders, interpreters were important in promotion, during campaigns, in diplomacy, and in ruling conquests. While crusade sermons were often preached, and almost always recorded, if at all, in Latin, although at times with macaronic elements, audiences demanded the vernacular. Where, as often, the preacher was foreign, interpreters became essential, as in Wales and Germany in 1188 or England in 1267.28 Communication presented similar problems on campaign. When persuading the cosmopolitan crusaders of the North Sea fleet in 1147 to attack Lisbon, the Portuguese bishop of Oporto used Latin as a lingua franca so that interpreters could translate his words to each separate linguistic group.29 This cannot have been confined to formal occasions; few large eastern cities until the mid-thirteenth century were internally linguistically homogeneous and most at some stage had to deal with the different languages of locals, in central and eastern Europe, Byzantium, Sicily or Cyprus. Familiarity through previous trade or pilgrimage eased some of these contacts, as witnessed by an eleventh-century Latin–-Greek phrase book.30 Dealing with the different languages of the Near East during the First Crusade’s march to Antioch would have been facilitated by Greek and Armenian interpreters; Tatikios, the Byzantine general attached to the crusade, was a Christianised Turk. The necessary further translations from and into Frankish languages may have depended on the bilingual skills of western settlers in Byzantium or French settlers in southern Italy and Sicily. At Antioch, negotiations with Kerboga of Mosul were conducted by Herluin, possibly a southern Italian Norman, who ‘knew both languages’, implying Arabic but probably not Turkish (an ignorance shared by Arab emirs), his naming a rare event for interpreters who in the sources usually remained anonymous or unmentioned.31

18. Woodcut from the Credo of the crusader John of Joinville showing crusaders and Arabs or Turks with an interpreter on crutches.

Once established in the Levant, western conquerors and settlers constantly required translators, to conduct fiscal, commercial and legal business and diplomacy: treaties, surrenders of castles and cities, and ransoms. Accounts of detailed discussions across linguistic divides are either formal inventions or suggest the availability of sophisticated language skills. Until the dragomen (from the Arabic tarjuman, interpreter) who shepherded later medieval Levantine pilgrim-tourists, it is hard to find servants of Arabic- and Turkish-speaking rulers with mastery of western tongues, so it appears much of the translation work – oral and scribal – rested with Syrian and Palestinian subjects of the Franks or increasingly with bilingual Franks themselves, such as Reynald of Sidon and Humphrey IV of Toron who appear as translator-negotiators with Saladin in 1191–2. The precision of diplomacy required deeper knowledge than demotic Arabic, French, or the lingua franca of port and marketplace. Parallel difficulties were encountered in the Baltic. When the German conquerors staged a Christian morality play for new Lettish converts at Riga in the winter of 1205/6, interpreters were needed to explain what was going on to no doubt bemused locals.32 Despite sharp cultural and religious divisions, prolonged settlement and rule extended the network of bilingual and multi-lingual officials, although identifying formal interpreting roles has proved elusive, in Outremer and elsewhere. Two remarkable features remain: the apparent ease of contact across linguistic divides and the absence in sources of a ubiquitous presence without which no crusade beyond western Christendom could have functioned.

19. Byzantine silk in the west: the cope of St Alboinus, Brixen, Italy.

The main driver of increasing western involvement in cross-sea trade lay in huge economic inequalities. Monthly shop rentals in Egypt may have matched entire annual royal revenues in some northern European kingdoms. Payment in gold for goods and slaves from the north made southern markets attractive for northern exporters, encouraging aristocratic investment, especially in cities that lacked an extensive rural contado or hinterland, such as Genoa, Venice or Amalfi. Subsequent economic and political problems in north Africa, Egypt and Byzantium then encouraged Italian shippers to cut out the Muslim and Jewish middlemen by building their own fleets and increasing the capacity of their ships. After the Norman conquest of Sicily, ports such as Palermo resumed their position as commercial hubs for the whole Mediterranean and facilitated plundering the north African coast, such as the Pisan raid on Tunisia in 1087. While perishable food remained restricted to local traffic, grain, olive oil, wine, sugar, timber, pottery, ceramics, as well as slaves, gold, ivory, silk and other textiles, began to circulate. As northern wealth increased, so did the import to Europe of higher-value goods from Egypt: ivory, rock crystal and spices. Trade knew few denominational boundaries. Eleventh-century Pisans decorated their churches with north African ceramic pottery. By the mid-twelfth century, Genoa’s combined trade with Egypt and north Africa made up about 45 per cent of the whole, while its largest market (30 per cent), Latin Syria, acted as the entrepôt for the Muslim interior.33

Growing commercial links opened new channels of transmission, some unexpected. In 1076, Pope Gregory VII (1073–85) was engaged in diplomatic exchanges with an-Nasir, emir of eastern Mauretania (in modern Algeria). Commending two papal associates to the emir, Gregory indulged in an uncharacteristic burst of ecumenism: ‘we believe in and confess, albeit in a different way, the one God, and each day we praise and honour him as the creator of the ages and ruler of this world’.34 Such knowledge of Islam in the west was extremely rare – at least in public – but ever more available. Both the Norman conquest of Sicily and the northern Spanish advances into al-Andalus (Toledo fell in 1085) placed significant Muslim populations under Christian rule. The lords of the Maghreb in north Africa, controlling one of the supply lines of gold and ivory from sub-Saharan Africa to the north, were clearly worth cultivating. By the twelfth century, permanent Italian trading posts dotted the north African littoral, in one of which, Bugie in Algeria, the Pisan merchant and mathematician Leonardo Bonacci, better known as Fibonacci (c. 1170–c. 1240/50), encountered Hindu-Arabic numerals, which he later popularised across western Europe. Similar protected and privileged status was afforded to Italians around the Mediterranean, from Algeria to Alexandria to Constantinople, a process in places accelerated but not initiated by the First Crusade. Cultural exchange flowed in the wake of commerce and conquest, such as Norman Sicily entertaining Fatimid art, architectural design and administrative practices, or the language skills of south Italian Normans. Generations before the First Crusade, the links between western Christendom, Byzantium and the Muslim world had been tightening, a process the great expedition to Jerusalem reflected, disturbed, but ultimately strengthened.

20. Eleventh-century Amalfitan coin with cufic epigraphy: ‘There is no God but God. Muhammed is the Prophet of God.’