THE FIRST CRUSADE

The impact of the Jerusalem war of 1095–9 on Latin Christendom can be exaggerated but was profound. It enhanced papal authority, invested western European culture in the politics of the eastern Mediterranean, and bequeathed an acrid legacy of unrealistic geopolitical ambition. The First Crusade disrupted those who took part; those it left behind; and those it encountered across Europe and the Near East. The religious dynamism of the Jerusalem war was shaped by a bleak world view of urgent conflict between good and evil, sin and virtue, eternal life or eternal damnation. However, while the conception of holy war rested on scripture, legend and law, its realisation was grounded in economic and social systems in which power and authority lay with arms-bearing ruling classes, the targets of Pope Urban II’s summons to fight: ‘the knights who are making for Jerusalem with the good intention of liberating Christianity . . . since they may be able to restrain the savagery of the Saracens by their arms and restore the Christians to their former freedom’.1 Beyond religious rhetoric, the campaign was framed by agricultural incomes; patterns of trade; the nature of lordship, kinship and service; and the ways men, materiel and money were assembled for war. Not everyone was convinced. Traditional beliefs in Christian pacifism or the primacy of the monastic ideal were not universally abandoned. Support for the First Crusade was political, following the contours of current controversies. Involvement was tempered by circumstance and self-interest. Large numbers of those who took the cross soon abandoned it. Others, such as the papally backed Norman rulers of the recently conquered Sicily, in contrast to their cousins in southern Italy, showed little appetite for the new adventure, preferring to consolidate their new possessions on the island and their trading relations with their Arab neighbours in north Africa and Egypt. Over a century later a northern Iraqi historian, Ibn al-Athir, described how Count Roger of Sicily (c. 1072–1101) reacted to suggestions of shipping a Frankish army to north Africa with a loud fart, adding the less percussive arguments that any such campaign would leave him out of pocket and destroy his existing agreements with the emir of Tunisia. Instead, Roger proposed: ‘if you are determined to wage holy war on the Muslims, then the best way is to conquer Jerusalem’.2 Although evidently ben trovato, the anecdote recognised the reality of Mediterranean politics, and by extension the politics of the crusade, driven by material concerns as much as religious compulsion.

The Plan

The plan to relieve Byzantium in Asia Minor followed by an invasion of Syria and Palestine was devised by Pope Urban II after a council held at Piacenza in Lombardy in early March 1095, at which Greek ambassadors asked for military aid against the Seljuk Turks. This was not the first such Byzantine appeal. As with earlier Greek invitations, it may have been accompanied with a substantial financial inducement, which might have contributed both to Urban’s enthusiasm and his ability to fund an extensive preaching and recruitment exercise and attract support.3 The decision to include the liberation of the Holy Sepulchre carried wide significance, not least by tapping into current eschatological excitement, a perception, encouraged by some popular preachers, a series of poor harvests and some unusual celestial phenomena, that the world was facing the Apocalypse, as prophesied in the Book of Revelation when Christ would return with a New Jerusalem. More pragmatically, Urban may already have been aware of requests for help from clergy in Jerusalem and returning pilgrims.4 The Council of Piacenza represented the first international church assembly of Urban’s troubled pontificate. Taking leadership of a movement to inspire the laity to aid fellow Christians in the east powerfully furthered papal assertion of primacy within Christendom, a natural corollary to Urban’s fostering of better relations with Byzantium and the eastern Church in a neat upstaging of his opponents, the German emperor Henry IV and his client pope Clement III. One later commentator, born during the preaching of the First Crusade, repeated gossip that Urban had plotted with the Normans of southern Italy to use the commotion created by the crusade to regain control of Rome, then in imperialist hands.6 Whatever the truth of this, Urban energetically exploited the Jerusalem war to his political advantage. He also recognised the recent precedents of Christian rulers’ conquests of Muslim territories. As he put it in 1098: ‘in our days with the force of Christians, God has attacked Turks in Asia and Moors in Europe’.7 Urban’s predecessors had regularly branded recoveries of lost Christian realms meritorious, religious wars, acts of liberation and restoration: in 1089, Urban himself had associated reconquest in Spain with penance and remission of sins.8

When he began promoting the First Crusade in 1095–6, Pope Urban II had been at the centre of international ecclesiastical politics for over fifteen years. Born Eudes (Odo) of Châtillon-sur-Marne around 1035 into a second-rung seigneurial family in Champagne, he received his early education and training at Rheims, where one of his teachers was the future founder of the austere Carthusian order of monks, Bruno of Cologne, who remained a lifelong mentor and confidant. After preferment as a canon and archdeacon at Rheims, in about 1068 Eudes entered the great Burgundian monastery of Cluny where he rose to be grand prior. Called to Rome to assist Gregory VII, in 1080 Eudes was installed as cardinal bishop of Ostia, quickly assuming a leading role in promoting and defending the pope’s ambitious moral and ecclesiastical policies, earning the disparaging epithet of Gregory’s pedisequus or lackey. He cut his teeth as an effective polemicist, networker, political operator and combative diplomat, especially while papal legate in Germany, 1084–5. Regarded as papabile on Gregory’s death in 1085, he was elected pope in succession to Victor III (1086–7) in 1088. Although committed to the full ideological quasi-monastic rigour of Gregorian reform, Pope Urban pursued his objectives with greater flexibility and collegiality, slowly managing to rebuild support against Emperor Henry IV and his protégé the anti-pope Clement III, as well as establishing a more cohesive identity for papal administration, known from 1089 as the curia. Preaching the First Crusade formed part of this process, providing Urban with a popular international cause, a unique diplomatic opportunity to consolidate reconciliation with Byzantium and a chance to ally moral reform with political action that involved the laity as well as clergy: most of the canons of the Councils of Piacenza and Clermont in 1095 addressed issues of church discipline. The alliance of secular and religious commitment found its definitive symbol in the granting to crusaders of the cross, a ceremony which Urban instituted at Clermont. The crusade sat easily in Urban’s wider policies of offering spiritual rewards for religious loyalty, as in his encouragement of Spanish Christian advances against the Moors, as well as exploiting his political alliances – notably with the Normans of southern Italy, whose crusade commander, Bohemund, was a personal acquaintance – and his ecclesiastical contacts: on the way to Clermont, Urban consecrated the high altar of the new church at Cluny. Theoretical papal authority over the crusade was maintained through legates, Adhemar of le Puy and then Daimbert of Pisa, and accepted by the expedition’s leadership, who wrote to Urban from Antioch in 1098 asking for his assistance after Adhemar’s death. Although Urban died a fortnight after the fall of Jerusalem in July 1099, before he could learn of the triumph, his mark on the memory of the campaign and on subsequent crusade history remained indelible.5

21. Urban II at Cluny, October 1095.

2. The routes of the First Crusade and that of 1101, with Urban II’s preaching tour of 1095–6.

Recruiting in northern Italy may have begun soon after Piacenza; a Lombard army reached Constantinople by the summer of 1096. Urban’s close diplomatic links with the leaders of the Normans in southern Italy probably alerted them to the papal initiative at an early stage. Between July 1095 and September 1096, Urban toured much of southern, central, western and south-eastern France. The novel presence of a pope north of the Alps caused a sensation, heightened as the ageing pontiff maintained a gruelling schedule of public appearances, often in the open, even in winter. Urban combined preaching with presiding over important local religious ceremonies, such as the translation of relics or the dedication of altars. Wherever he went he negotiated with local ecclesiastics and lords for their support for the Jerusalem scheme. Letters and legates were sent to those regions that, because of distance or political impediment, such as the excommunications of the king of France and the emperor of Germany, he could not visit. By the time he held a council at Clermont in the Auvergne in late November 1095, Urban had already secured the commitment of a string of notables. The council itself was intended to attract secular as well as ecclesiastical leaders from across France. In a carefully staged and choreographed performance, at the end of the assembly, on 27 November, Urban preached on the Jerusalem war.

It is not known what Urban said. No verbatim record exists, and attendance was patchy. The decrees of the Clermont council chiefly reiterated papal policies on church authority, independence, organisation and discipline. The decree on the Jerusalem war, which only survives in seventeenth-century copies of a dossier of council documents kept by one of the attendees, the bishop of Arras, offered a special form of penitential exercise that forged together Gregory VII’s idea of penitential violence, the papal concept of in-violate church freedom, and a campaign to Jerusalem.9 Church protection was extended to those who undertook this task and to their property. Tendentiously, the pope’s God-given authority over human spiritual affairs was assumed. The uniquely generous spiritual benefit of full remission of penance was open to all who confessed their sins. This full remission coupled with the explicit goal of Jerusalem transformed a mundane scheme to provide mercenary troops to Byzantium into a cause of ostensibly transcendent significance. Unlike his mentor Gregory VII’s similar proposal in 1074 to assist Byzantium and march on to Jerusalem, Urban’s provided a clear structure of message, response and reward: the positive incentive of remission of penance instead of Gregory’s bleaker, more amorphous emphasis on martyrdom; the replacement of Gregory’s vague promise of ‘eternal reward’ with precise spiritual and temporal rewards signalled by swearing a vow and taking the cross.10 Oaths provided a familiar, serious bond of commitment. Simple, memorable slogans were deployed: ‘Take up your cross and follow me’, ‘Liberate Jerusalem’, ‘expel the infidels’, ‘earn salvation’, ‘God Wills it’. The subsequent campaign of public ceremonies, private conversations, sermons, letters, legates, and the recruitment of local opinion formers, notably monastic networks, displayed propaganda management of a high order.

The idea that Urban had originally intended only limited aid for Byzantium is contradicted by his proposals’ inclusion of Jerusalem, the unique spiritual rewards on offer, and his own extensive recruitment tour and efforts to communicate with regions beyond his itinerary. Letters, eyewitness accounts and land deeds of departing crusaders paint a fairly consistent outline of the pope’s plan: a penitential military campaign to Jerusalem to recover the Holy Sepulchre, free eastern Christians and thus, in Urban’s own words, ‘liberate Christianity’.11 Relief of the burden of sin struck a chord with arms-bearing aristocrats whose warrior values sat awkwardly with increasingly well-articulated clerical insistence on the unavoidable penalties of temporal sin. Many likened the expedition to a pilgrimage. Urban’s few surviving letters used more general words with penitential associations of journeying and labour (iter, via, labor), while at the same time employing the precise language of divinely ordained sacralised holy warfare (procinctus, expeditio). Witnesses remembered the pope emphasising the armed nature of the struggle at Limoges in December 1095 and a war ‘to hunt the pagan people’ in Anjou in March 1096. The message got through: ‘to fight and to kill’ the defilers of the Holy Sepulchre, as one Gascon charter put it. The sense of a Christian militia suffuses crusaders’ campaign letters.12

At Clermont, Urban announced the appointment of Bishop Adhemar of Le Puy as his surrogate to lead the expedition and the date of his departure, 15 August 1096. Land routes and a general rendezvous and muster at Constantinople must have been agreed in advance of the contingents setting off. Despite increasing naval capacity, the shippers of Italy hardly possessed the resources or technology to carry very large armies, with adequate rations and horses, across the Mediterranean. Equally, crusade commanders probably lacked sufficient ready cash to pay shipping costs or the appetite to test the ubiquitous landlubbers’ suspicion of the sea that many would never have seen before. Strategically, the question as to why the crusade took three years to reach Jerusalem rather than the few months of a sea voyage, can be explained by the bifurcation of Urban’s plan: help for eastern Christendom and the recovery of Jerusalem. Acceptance of the Greek invitation, and perhaps money, made Constantinople the necessary and obvious first destination. The main land armies mustered across western Europe in the autumn of 1096; reached Constantinople between November 1096 and May 1097; and gathered as one host at the siege of Nicaea by early June 1097, a process speaking loudly of coordination with the Byzantines.

The military effort stretched from the Mediterranean to the North Sea. Some recruitment appeared distinct from the papal campaign. The excommunicate French king, Philip I, held a conference in Paris in February 1096 to discuss the crusade. Meanwhile, a separate preaching initiative, begun perhaps before the Council of Clermont, was conducted by the charismatic diminutive Picard preacher Peter the Hermit. Later a figure of legend, in practice he apparently combined revivalist oratory with the ability to raise and organise troops, including a number of lords from the Ile de France and surrounding regions, and to provide active leadership for a substantial army of cavalry and infantry from northern France and western Germany.13 Peter retained some standing in the crusader armies even after his own forces had been cut to pieces in Asia Minor in September 1096. How Peter acquired sufficient authority to command such forces is hard to fathom. Remarkably, his contingents – possibly tens of thousands strong – were ready to depart by early March 1096, reaching Constantinople in July and August. His relationship with Urban’s mobilisation is unknown, although early accounts after 1099 linked the two. Peter’s apparent pitch of serving Christ and restoring Jerusalem certainly echoed Urban’s.14

Peter, known as the Hermit (d. c. 1115), was a popular travelling evangelist from Picardy who preached moral and social reconciliation in northern France, establishing a strong reputation as a charismatic ascetic holy man in the years before the First Crusade. All chronicle accounts note his leading the first wave of crusaders eastwards that came to grief in Asia Minor in the autumn of 1096 and later his role at Antioch in heading the crusaders’ embassy to Kerboga of Mosul. Some suggest his continuing prominence once the expedition had taken Jerusalem. After the crusade, he is said to have returned home, founding a religious house at Neufmoutier near Huy (in modern Belgium). One western German tradition ascribed the initiative for the crusade to Peter, calling him the ‘primus auctor’.15 This tradition gained historiographic traction by being included, alongside prominence given to Urban II, in William of Tyre’s Historia, the great late twelfth-century historical compendium of crusade history that dominated perceptions of the First Crusade until the nineteenth century when Peter’s initiating role was dismissed as fiction.

Recent scholarship has reassessed Peter’s contribution, noting that, while also a figure of legend, the historical Peter combined his revivalist oratory with raising and organising a coherent thousands-strong armed force, largely of infantry but led by lords and knights.16 This force set out for the east in March 1096, only a few months after the Council of Clermont following Peter’s preaching in areas Urban avoided, from Berry, the Orleannais, Champagne to Lorraine and the Rhineland, with additional recruitment from the Ile de France. The speed of his army’s departure suggests he began to promote the Jerusalem journey before the Clermont speech, possibly in collusion with the pope, indicated by the only detailed account of Peter’s preparations. This describes how Peter, prompted by his own ill-treatment on pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre, and armed with a written appeal for western aid from the Patriarch of Jerusalem (neither of which is impossible or even improbable), persuaded Urban to launch the crusade. Peter’s own preaching lacked offers of the cross and in retrospect was seen as more populist than the pope’s, aimed beyond the knightly classes. Yet the two campaigns shared essential elements: a call from the east; the plight of Jerusalem; the direct order of Christ (in Peter’s case via a dream); and the offer of spiritual reward. It is easily conceivable that Urban, in exploiting the Greek invitation for aid into his scheme of a papally led Christian renewal, incorporated appeals from the Christian community in Jerusalem and the evangelical activism of Peter the Hermit.17 The legend may not be groundless.

22. Peter giving out crosses.

Receiving the cross formed part of a process of engagement driven by material as well as emotional and religious forces. No recruit could hope to par-ticipate without material assets, his or her own or someone else’s. The offer of church protection probably agreed at Clermont assumed crusaders possessed property.18 Lords subsidised their entourages and relatives. Poorer crusaders without such material support had to abandon their journey. The staggered times of departure in 1096 depended on the harvest, raising money from property deals or recruits finding a paymaster. Accounts of the crusade note the large-scale involvement of what were frequently, at times derisively, termed ‘the poor’ (pauperes). Leaving aside the moral heft of the ‘poor in spirit’ (Matthew 5:3), the ‘poor’ on crusade were defined in comparative terms, not necessarily indigent but non-rich, subsidised by others. Such numbers grew proportionately as the campaign drained recruits’ assets, necessitating the creation of common funds to bail them out.19 Economic and financial constraints provided the frame for the expression of religious enthusiasm through emotional triggers of anxiety (fear of sin, hell, or bogeymen infidel), hope (salvation, virtuous conduct, self-improvement, enhanced status), revenge (for Christian and by analogy Christ’s suffering) and reward (remission of penalties of sin, privileged legal protection, employment) that sought physical resolution through the military campaign. The crusade was always about more than a supposed existential Turkish threat. In records of their fund-raising transactions, departing crusaders were depicted as desiring escape from the burden of sin through the penance of the crusade. However, the Clermont decree implied that, given righteous intent, spiritual and material ambitions did not contradict one another. One eyewitness later described Urban offering knightly recruits self-respect, fame and a land ‘flowing with milk and honey’ (Exodus 3:8). Another had the pope promising crusaders the possessions of their defeated enemies, the usual accompaniments of successful warfare.20 A famous crusader battle cry held out the prospect of ‘all riches’ (divites) as a reward for steadfastness in faith and victory in battle.21 The ambiguity of spiritual and material gain was inherent.

Recruitment spread unevenly but extensively: in France, the Limousin, Poitou, the Loire valley, Maine, Chartrain, Ile de France, Normandy, Burgundy, Languedoc and Provence; in Italy, Lombardy, the Norman south and the ports of Liguria and Tuscany; in Germany, the Rhineland and western provinces. Enthusiasm is recorded from Catalonia. There is limited evidence of participants from Denmark and England. However, the English paid a land tax levied by King William II (1087–1100) to raise 10,000 marks for mortgaging the duchy of Normandy to subsidise his brother Duke Robert’s expedition. Everywhere, the lead was given by what a Genoese observer called the ‘better sort’ (meliores): lords, abbots, members of mercantile urban elites.22 Participation relied on existing networks of lordship, kinship, clientage, shared locality, commerce and employment, and therefore centred on aristocratic, ecclesiastical or commercial communities, families and courts with their immediate dependants – relatives, tenants, military households, client clergy, servants. The Church furthered international contacts through its increasingly cosmopolitan episcopates and monastic orders. Towns and cities provided focal points for recruitment and muster, news and recruitment passing along trading networks. Crusading traditions quickly became established in market centres such as Limoges, Poitiers, Tours, Chartres, Paris, Troyes, Lille, Cologne, Milan and Genoa. The high nobility operated internationally through extensive dynastic connections across regional frontiers.23

The total number of those who left for the east is unknowable. Some estimates put the figure as high as 70,000–80,000 recruited during the year after Clermont.24 A regular stream of reinforcements in smaller groups joined them during the three-year campaign, by land but also by sea, chiefly on Italian fleets from Genoa, Lucca and Pisa. Many who took the cross thought better of it, could not find a patron or failed to raise adequate funds, without which, it was later observed, participation was impossible.25 The impression given by crusaders’ surviving property grants – sales or various forms of mortgage chiefly to monasteries, in return for cash, materiel or pack animals – is of free-standing, independent, knightly or noble recruits incurring considerable capital loss, many times annual landed income. However, these records are those of the leaders not the led, the paymasters not the paid. Most of those who went with the First Crusade at some stage, some at every stage, received payment in kind or cash, sometimes disguised as gifts, much of it in addition to basic survival rations. Lords paid their retinues and got their clerks to keep written accounts. On the march, payment could attract new followers and create fresh allegiances, a process fully exploited by ambitious junior commanders such as Bohemund’s nephew Tancred of Lecce. Crusaders took considerable quantities of silver bullion with them in coin and ingots; a Burgundian knight received 2,000 shillings on just one land deal with the abbey of Cluny; Godfrey of Bouillon extorted 1,000 silver pieces from the Jews of Cologne and Mainz as well as raising 1,300 silver marks from selling his estate at Bouillon.26 Affluent crusaders took negotiable wealth with them: jewels, plate or luxury textiles. Although very little gold was available until the crusaders reached the eastern Mediterranean, most leaders took some if they could. On campaign, the crusaders’ resources were regularly replenished: by gifts, bribes and payment from the Greeks; tribute and protection money from cowed opponents; and booty from victories and conquests. The scramble for supplies, subsidies for poorer crusaders, arguments over exchange rates, and the creation of central communal funds witnessed the material imperatives.

Not all fund-raising was loss. Mortgages and ecclesiastical protection de facto recognised a crusader’s title to property. The pious motives attributed to crusaders in some of the charters recording such financial transactions may have been genuine, or the gloss of the clerical scribe, or simply technical formulae indicating gifts rather than sales or mortgages.27 Nevertheless, the availability of the necessary moveable wealth is striking, especially given the series of very poor harvests before the bumper crop of 1096, and the late eleventh-century western European dearth of silver. Even with the unlocked bullion assets of monasteries, the apparent surplus of liquid capital indicates developing monetisation in commerce and artisan trades. Wealth was no longer confined to ecclesiastical corporations, successful merchants and landed aristocrats. The head chef of Count Stephen of Blois, Hardouin Desredatus, possessed vineyards, land and houses that he assigned to the abbey of Marmoutier before setting off east. The abbey, near Tours in the Loire valley, played an active role in seeking such deals, monks and abbot openly touting for trade in what they clearly saw as a profitable business as well as spiritual opportunity.28

As the armies lumbered east from the early spring to late autumn of 1096, led by expanded retinues of great nobles, lesser lords and wealthy knights, the pattern of mutually sought-after lordship, secured by wages, gifts, subsistence, service and shared booty, provided the glue that held together the crusade. New subsidised units formed following a lord’s death, impoverishment or another’s success. Groups from the same area and across the social spectrum could travel together, mess together and pool resources. All recruits would have been used to acting and making decisions as a community. Alongside hierarchical lordship, much of society operated communally, from crop planting to law courts. On the crusade itself, the non-noble elements, characterised as the populus, periodically acted in concert to influence the decisions of the leaders who regularly consulted them. Besides the non-combatant support staff necessary to any armed force – cooks, farriers, carpenters, blacksmiths, writing clerks, valets, priests, prostitutes, laundresses and others – the First Crusade armies attracted non-fighting pilgrims seeking military protection. Some apparently set out with their belongings, intent on settling near the Holy Places. If so, hope proved a mirage or a nightmare. Non-combatants and the less well-off tended to be the first and heaviest casualties from disease, hunger and exhaustion: accounts of their privations and losses make harrowing reading. The genuinely poor could not go on crusade with much prospect of progress let alone survival.

The Campaign to Syria, 1096–7

The campaign of the First Crusade fell into four stages. The first saw the western forces converge on Constantinople in the autumn, winter and spring of 1096–7. In the second stage, over the six months from June 1097, the crusaders, acting in collaboration with the Byzantines, captured Nicaea in western Asia Minor, forced a passage across Anatolia, annexed Cilicia and besieged Antioch in northern Syria. During the third stage, in 1098, the crusaders emancipated themselves from the Greek alliance as they took Edessa, Antioch and its surrounding regions for themselves. The final act, beginning in January 1099, saw most of a much reduced crusade army march south into Palestine where, on 15 July 1099, Jerusalem fell after a month’s siege, a triumph secured by victory over a Fatimid relief army at Ascalon in August. The majority of survivors then returned home leaving meagre garrisons in Jerusalem, Antioch and Edessa.

Two main routes to Constantinople were used. One went south-east from the Rhineland to follow the Danube to Belgrade before striking south-east across the Balkan peninsula to the Byzantine capital. This was used by forces that passed through or originated in western Germany, such as the armies of Peter the Hermit, some German counts, and two substantial contingents raised by two German priests, Gottschalk and Volkmar, which were destroyed in Hungary during June and July 1096 after provoking disturbances over supplies and markets. The surviving armies, including Peter the Hermit’s, passed down the Danube from the early spring of 1096 onwards. Some months later, they were followed more peacefully by Godfrey of Bouillon, duke of Lower Lorraine, and his Lorrainers. The second route east led to the ports of Apulia in southern Italy and the short sea crossing to the Albanian coast and the old Via Egnatia across the Balkan peninsula to the Byzantine capital. This was used by the armies from northern France led by Hugh of Vermandois, brother of Philip I of France, Robert of Normandy, and the counts Eustace III of Boulogne, Robert II of Flanders and Stephen of Blois, as well as by southern Italian Norman troops under Bohemund of Taranto. The Lombards who reached Constantinople by August 1096 plausibly also travelled the Apulia–-Albania–-Via Egnatia route. These routes were familiar from trade and pilgrim traffic. Exceptionally, Raymond of Toulouse’s large force, accompanied by the legate Adhemar of Le Puy, marched from Provence through Lombardy, around the head of the Adriatic and down the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic before picking up the Via Egnatia, a longer journey that crossed difficult terrain where the Provençal troops encountered local hostility. It has been suggested that Raymond’s Dalmatian itinerary had been planned with Alexius I to discipline a rebellious Serb leader, Constantine Bodin.29 While evidence for this is circumstantial, general Byzantine-papal-crusader cooperation may be assumed, not least in the provision of supplies and markets in Greek territory and the well-framed diplomatic preparations that greeted the crusaders when they reached Constantinople.

3. Crusade attacks on Jews, 1096–1146.

One unplanned consequence of the mass recruitment saw lethal attacks on Jewish communities of the Rhineland in May, June and July 1096, initially orchestrated in Speyer, Worms, Mainz and Cologne by troops under Count Emich of Flonheim. Feeding off local economic and social tensions, the violence was fuelled by the aggressive Christ-centred crusade rhetoric of victimhood, resentment and revenge. Although no part of official policy, these anti-Jewish atrocities exposed a fissile intolerance inherent in the crusade’s ideology (see ‘Jews and the Crusade’, p. 80).30

The second stage of the crusade saw the western forces operating as Emperor Alexius’s mercenaries, hired confederates of the Byzantine state. On reaching Constantinople, crusade commanders swore personal oaths to the emperor, receiving lavish gifts of gold, silver, jewels, cloaks, textiles, food, horses and military equipment in return. In the crusaders’ own testimony, desire and expectation of material reward are palpable. Certain objects conveyed more than aesthetic or financial value. Tancred of Lecce, Bohemund’s ambitious nephew, asked – unavailingly – for Alexius I’s enormous imperial tent ‘marvellous both by art and by nature . . . it looked like a city with turreted atrium [and] required 20 heavily burdened camels to carry’. Despite its highly inconvenient bulk, Tancred intended the tent as a meeting place for his growing band of clients and followers. Just as money allowed the great to attract support, so Tancred’s hoped-for tent would have elevated his status. Display formed a crucial aspect of lordship, on crusade as at home. The luxury that attended rich crusaders on campaign played a social and political role beyond private gratification.31 Alexius, who similarly used conspicuous wealth to politically dazzle and impress, understood this. He was paying on a number of levels for specific military aid.

The initial object was the recapture of Nicaea, within striking distance of Constantinople, held by the Seljuks since 1081. Earlier western recruits had been stationed nearby, as had been the forces led by Peter the Hermit until their near annihilation by the Turks in September 1096. Alexius’s wider strategy included challenging Turkish power in Anatolia, Cilicia, Armenia and northern Syria, with Antioch fixed as a target. Using the crusaders on his eastern flank left Alexius freer to combat Turkish threats in the Aegean. In addition to money and supplies, he provided strategic advice, regional contacts, for example with Armenian émigrés, and diplomatic intelligence, including putting the crusaders in touch with the Fatimids of Egypt. Direct Byzantine military cooperation was provided at the siege of Nicaea and a Byzantine regiment accompanied the march across Anatolia to Antioch to protect Alexius’s interests and receive the surrender of captured cities. As one veteran noted, the crusaders needed Alexius as much as he needed them: ‘without his aid and counsel we could not easily make the journey’.33

Although no crusade was launched against the Jews of western Europe, their communities were profoundly affected: directly from crusaders’ physical attacks and financial extortion; and indirectly by increasingly overt anti-Semitic prejudice and discrimination arising from the development of a culture of aggressive Christian piety and religious xenophobia that crusading reflected and stimulated. Both lay and ecclesiastical Christian authorities were conflicted. Secular rulers generally welcomed Jewish commercial and financial activity as sources of revenue, which encouraged them simultaneously to protect and exploit Jews within their jurisdictions. Jews’ urban trades, businesses and access to liquid capital made them attractive as both protégés and milch cows. As rich corporations, churches and monasteries similarly took advantage of Jewish finance. At the same time, official church teaching created a contradictory tension. On the one hand, Jews were depicted in the liturgy and elsewhere as responsible for the Crucifixion and obstinately blind to the Christian revelation: in short, enemies of Christ. On the other, the Book of Revelation describes how the final conversion of the Jews will mark a stage in the Apocalypse and the fulfilment of God’s providential scheme and therefore implictly demands protected status for Jews. The crusades initially sharpened these contradictions before contributing to the spread of a climate of cultural uniformity and religious intolerance in which Jews found themselves increasingly exploited, marginalised, ghettoised and excluded.

Jewish communities spread from the Mediterranean into northern Europe from the tenth century, becoming established in some numbers in market towns and cities across parts of France and western Germany, increasingly prosperous regions later, not coincidentally, significant as centres of crusade recruitment. Attacks on these communities did not start with the crusades, reports of the Egyptian caliph al-Hakim’s destruction of the Holy Sepulchre in 1009 provoking anti-Jewish violence in France. However, the concerted atrocities inflicted on Jewish communities in the Rhineland and northern France in 1096 during the early stages of the First Crusade appeared of a different order and set a new pattern for persecution that revolved around money, faith and civil protection. From May until July various Franco-German contingents of crusaders wrought havoc in Jewish communities the length of the Rhineland and elsewhere in northern France. From both Christian and Jewish sources, their motives appeared both material and religious. The desire to seize Jewish cash to pay for crusade expenses was widely shared; Godfrey of Bouillon extracted 1,000 marks from the Jews of Cologne and Mainz, later victims of the depredations of the followers of Count Emich of Flonheim, who committed a series of the worst outrages. The desire for money was nonetheless closely allied to a declared collective sense of vengeance on enemies of the cross. While religious claims may have acted as a cover for violent mercenary grand larceny, it appeared to some victims as a potent ideological inspiration, supported by the many instances of enforced conversion. Such excesses may have aided corporate bonding among the crusaders, a source of identity and the first action of the campaign. It also signalled a failure and collapse of political control by church and secular authorities: in attacking the Jews, Count Emich was clearly defying the authority of Emperor Henry IV as well as the local prince-bishops.

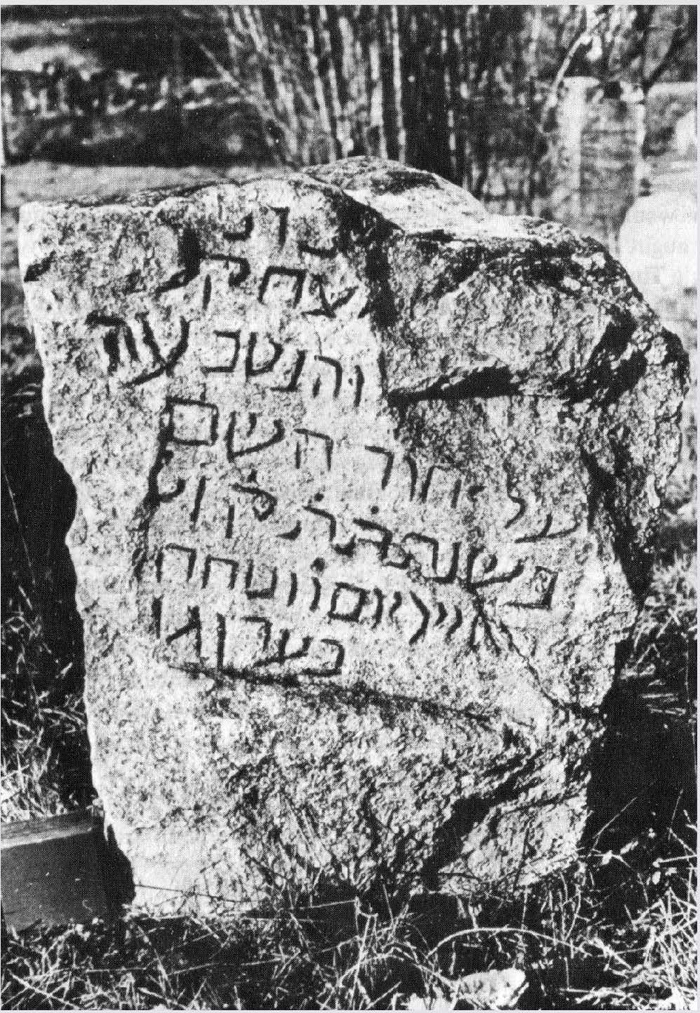

23. Tombstone of a Jewish victim of crusader violence, Mainz, 1146.

This combination of material greed, sincere or feigned enthusiastic religious hostility, and the limits of establishment protection was displayed again during the Second Crusade, when, among other outbreaks of persecution, a charismatic Cistercian preacher Radulph whipped up anti-Jewish violence again in the Rhineland in 1146; and in England during the early stages of the Third Crusade in 1189–90, attacks that culminated in the massacre and mass suicide of Jews at York in March 1190. The authorities’ loss of control on these occasions contrasts sharply with the effective public protection afforded the Jews of Mainz by Frederick Barbarossa in 1188. However, the dangers for Jewish communities were not confined to sporadic explosions of violent hostility but embraced a gradual erosion of social tolerance, while whatever wealth they possessed was never immune from peaceful sequestration. Although successive popes from Eugenius III’s 1145–6 crusade bull onwards had outlawed direct involvement of Jewish credit in funding crusades, as this risked siphoning crusaders’ money to Jews, secular rulers felt free to extort money directly for their crusades, a move advocated by influential clerical anti-Semites such as Abbot Peter the Venerable of Cluny (d. 1156). In England, Jews were tallaged (a form of arbitrary royal expropriation) for crusades in 1188, 1190, 1237, 1251 and 1269–70. In 1245 the First Council of Lyons directed that all Jewish profits from interest be confiscated for the crusade. In 1248–9, to help pay for his crusade, Louis IX of France, a notoriously devout anti-Semite, expelled Jewish money-lenders and seized their assets.

It is incontestable that the culture of the crusade encouraged the range of disparagement of the Jews. During the later twelfth and thirteenth centuries, increased official alarm, academic contempt and political violence aimed at religious unorthodoxy and dissent, coupled with, in promoting the crusade, greater emphasis on the figure of Christ Crucified, placed those branded as enemies and killers of Christ in an ever more precarious position. Material exploitation was matched by deliberate social alienation in the name of faith, witnessed equally by formal discrimination, such as the legislation passed by the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, and the emergence of blood libels from the mid-twelfth century (the first, invented in the 1150s by monks at Norwich cathedral priory, concerned an unsolved murder in 1144 of William an apprentice tanner). While the crusades did not create anti-Semitism, crusading’s ideology and practice highlighted some if its core sources, from financial resentment in a cash-strapped but increasingly monetised society to the promotion of an exclusive religion as marker of social identity. For those encouraged to think that their intent to fight the infidel represented an ultimate laudable ambition, Jews made awkward neighbours.32

The muster of the armies at Nicaea encouraged field cooperation and unity in a host numbering many tens of thousands speaking many different languages. During the siege (May–June 1097) the leaders had to coordinate their actions consensually and pool resources: a common assistance fund was created, paying, among other things, for siege engines and engineers. The need for unity became even clearer after the fall of Nicaea (19 June). On 1 July, only a few days after setting out towards Syria, the expedition narrowly escaped disaster when its vanguard under Bohemund and the Byzantine general Tatikios became separated from the rest of the army and was attacked by a substantial Turkish force. Only the timely arrival of the main army saved the day and led to a sweeping victory, known subsequently as the battle of Dorylaeum. There followed a painfully slow march (perhaps between 5 and 11 miles a day for up to 800 miles) in harsh summer conditions. A number of Turkish-controlled towns and cities capitulated. Casualties from heat, hunger and disease were high. In September, at Heraclea, facing the barrier of the Taurus Mountains, the army divided. The main force followed a northern route through potentially friendly Armenian territory, approaching Syria from the north-west. Smaller contingents under Tancred of Lecce and Baldwin of Boulogne turned south, competing against each other as they swept up coastal towns in Cilicia before reuniting with the main army to besiege Antioch in October. This pincer strategy had probably been devised on Greek advice to maximise Armenian Christian support in the Taurus region and Cilicia while cutting off Antioch from the resources of its hinterland.

Antioch 1097–8

The crusade’s third stage, the siege of Antioch, followed by a six-month hiatus in the expedition’s progress, established the crusaders’ independence from Byzantium, at the same time forging within the army a distinctive identity. Battered by disease, hunger, fear, anxiety, uncertainty, heavy casualties and battle trauma, the crusaders apparently developed a fierce sense of providential community in adversity, encouraged by stories of heavenly assistance, visions and miracles. Genuine demotic impulses were exploited by the high command to keep the beleaguered army intact, fostering the crusaders’ image as the new Israelites, specially chosen, tested and protected by God, in death as in life. This provided a defining template for subsequent crusades. With the departure of the Greek regiment and the subsequent much -publicised and highly controversial failure of Alexius to help the crusaders, Antioch transformed the crusade from a subordinate mercenary army into the fiercely independent, self-conscious army of God.

24. Antioch in the 1830s showing the fortifications on Mount Silpius behind the city.

The first siege lasted from 21 October 1097 until the city fell on 3 June 1098. The crusaders then immediately found themselves besieged by a large relief army from Mosul. This second siege lasted until the breakout of the crusader forces on 28 June, which achieved a surprising but decisive victory. Antioch in 1097, a city of Greeks, Armenians, Arabs and Turks, was ruled as a semi-autonomous dependency of Aleppo by its governor Yaghi-Siyan. Throughout the first siege, the crusaders had been unable to surround Antioch completely or prevent the city being supplied and reinforced. Despite defeating relief armies from Damascus (late December 1097) and Aleppo (February 1098), and constructing a number of siege forts around the city, Antioch only fell to them through the treachery of a disaffected local commander who helped spirit a small force under Bohemund over the walls at night (2/3 June). Even then the citadel remained untaken, only surrendering after the victory of 28 June. The concentration of tens of thousands of besiegers created severe problems of supplies, provisions being sought from as far away as Crete, Cyprus and Rhodes as well as the northern Syrian hinterland. As the winter of 1097–8 progressed, famine and disease became endemic. Desertions mounted, ironically assisted by the arrival in Syrian waters of fleets from Italy, Byzantium and possibly northern Europe. Morale sagged. Privations deepened. With the threat of Turkish relief forces undimmed, to stiffen resolve the leadership began to circulate stories of heavenly soldiers and saints fighting for the crusaders, and of visions and dreams that confirmed the providential nature of their cause and the certainty of paradise for fallen comrades.

The departure of Tatikios in February 1098, possibly to secure more supplies and troops, allowed some, notably Bohemund, to suggest treachery and dereliction from the agreements sworn between the crusaders and Alexius in Constantinople. These oaths, which can only be reconstructed from subsequent special pleading from all parties, seemingly implied that, in return for his active assistance, Alexius would receive the allegiance of crusader conquests, at least as far as Syria. What was envisaged for acquisitions further south is wholly unclear, except that some form of imperial overlordship would probably have been expected by the Byzantines. By the time they reached Antioch, the crusaders may well not have worked out how to organise a political settlement for Jerusalem. Their early contact with the exiled Greek Patriarch Simeon of Jerusalem may have alerted them to the complexity of implementing their slogan of liberation for Palestinian Christians.34 The destiny of Antioch, by contrast, presented a more clear-cut objective. It is possible that Alexius had offered Bohemund a role as client ruler of a buffer province in Cilicia or northern Syria. However, buoyed up by his success in leading the defeat of the Aleppan army in February 1098, Bohemund developed an independent strategy to establish his own principality, a move eased by Tatikios’s departure. As the crusaders stayed outside Antioch, foraging across the region, political options opened up. Fatimid negotiators appeared in the crusaders’ camp in February and March 1098. A splinter group under Baldwin of Boulogne, who had again left the main army in October 1097, had offered service to Armenian lords in the upper Euphrates region, a move culminating in Baldwin’s assuming control of the city of Edessa in March 1098. As commander of an alien elite military corps in control of a Near Eastern city, Baldwin was adopting a role similar to a Turkish emir or atabeg. In doing so, he showed his former comrades what was possible.

The outcome at Antioch assumed regional significance. With the crusaders still receiving supplies from Byzantine territory, naval reinforcements from the west presented a threat to the ports of northern Syria. In the wake of the failures of the rulers of Damascus and Aleppo, the atabeg of Mosul, Kerboga, assembled a large coalition, drawing allies from southern Syria, northern Iraq and Anatolia. His spring offensive in 1098 sought to impose his rule from the Jazira region of Syria to the Mediterranean. Antioch formed only one part of this strategy, as was apparent from Kerboga’s unsuccessful three-week attempt to capture Baldwin of Boulogne’s Edessa in May. This delay saved the crusade itself as Kerboga’s army reached Antioch only hours after the westerners had entered the city and gained the protection of its walls. Bohemund’s own parallel ambitions had also become clear. By the end of May, he had persuaded his fellow leaders to agree to his keeping Antioch if he could capture it and if no help came from Alexius. Four days later, on 2 June, a possible rival, Stephen of Blois, who only two months earlier had been boasting of his appointment as the expedition’s ‘lord, guardian and governor’, conveniently fled the siege.35 Once he had gone, Bohemund revealed to his remaining colleagues his plan to enter the city with the assistance of an Armenian commander of one section of the walls.

Timing was crucial for Bohemund. Not only was Kerboga’s army fast approaching from the east, but he may have got wind that Alexius, accompanied by thousands of new crusaders, was slowly advancing across Anatolia to consolidate the rapid gains the Byzantine-crusader army had secured the previous year. While it is unlikely that Alexius, a cautious commander and more concerned with western Asia Minor than northern Syria, had firmly decided to advance as far as Antioch, his caution was compounded by learning of the crusaders’ plight directly from Stephen of Blois in late June at Philomelium (Asksehir). The emperor withdrew westwards as a precaution against being cut off by renewed Turkish incursions. While it would stretch the evidence to suggest that Bohemund had planned Stephen’s departure and loaded him with forecasts of doom in order to persuade Alexius to withdraw, Stephen’s absence and the emperor’s failure to proceed to Syria suited Bohemund’s purpose. It left him free to demand Antioch and provided a very effective weapon of propaganda to excuse the crusaders’ breaking their obligations to the emperor on the grounds of Alexius’s own supposed breach of contract.

The sensitivity of the issue was reflected in the attention it received from later commentators, both Latin and Greek, who identified it as a pivotal moment in subsequent Byzantine relations with the western principalities in the Near East and later crusade expeditions. However, despite the mutual polemics, the breach was not total. Negotiations over Greek military help only finally ended in April 1099. Food still came from Byzantine territories; diplomatic contacts with Armenians and Fatimids, brokered by the Byzantines, were maintained; some crusade commanders, such as Raymond of Toulouse, still acknowledged Byzantine primacy and accepted Greek assistance. However, the removal of Byzantine direction in 1098 transformed the First Crusade into an independent player in Near Eastern politics whose uncomfortable ideological ambitions challenged regional expectations. The crusaders’ increased autonomy was further supported by western fleets that allowed them independent access to supplies from across the eastern Mediterranean, naval protection for the land operations, and direct material aid, their presence arguably tipping the military balance towards the crusaders.

None of this would have mattered without victory at Antioch. After the occupation of the city on 2–3 June 1098, now themselves besieged by Kerboga, with Antioch’s citadel still in Turkish hands, and the impossibility of defending the whole circuit of the walls, the crusaders plumbed new depths of desperation. Lack of food, high prices and illness sapped the army’s physical strength. The vital supply of horses fell dangerously low. Morale was corroded by fear and helplessness at the only too visible prospect of imminent brutal death. Collective nerve snapped in a night of mass panic and flight (10–11 June). The expedition was saved by deft deployment of the carefully fostered sense of providential and eschatological purpose developed over the previous six months. In the days after the night of panic, supportive visions of Christ and the Apostles were reported to have been received by members of the Provençal army. One vision usefully indicated that the Holy Lance that had pierced Christ’s side on the cross was buried in Antioch’s cathedral. Despite general scepticism, the claim was tested and on 14 June an object appropriate for the Lance (or rather its spear-head) was unearthed. The leadership reinforced the consequent positive change in mood with mass rituals of solidarity and penance and by imposing puritanical rules of behaviour. However, visionary politics failed to alter grim military reality. An embassy to negotiate with Kerboga in late June, led by the neutral figure of Peter the Hermit, may have sought a negotiated surrender to permit the crusaders to withdraw.36 If so, it failed, leaving the crusaders little option but to chance survival on battle.

The crusader victory against the odds at the battle of Antioch (28 June 1098) saved the expedition and created a new political context. Effectively recreating under new management the former Byzantine province of Antioch lost to the Turks in 1084–5, perhaps a Byzantine strategic aim all along, the crusaders were now firmly established in northern Syria, with control over the lower Orontes valley and access to Mediterranean ports, a position consolidated over the following six months as more towns were captured. The beginnings of western administrative rule emerged in Antioch and elsewhere; a Latin bishopric was created at al-Bara. Urgency dissipated, as the army enjoyed novel peaceful prosperity while their commanders jockeyed for power in Antioch and exploited regional resources. The death of Adhemar of Le Puy (1 August 1098) removed a unifying and purposeful influence. With Bohemund successfully defending his hold over Antioch, Raymond of Toulouse, no less eager to secure a Near Eastern principality for himself, led raids that secured a swathe of territory to the south of the city, including Ma’arrat al-Numan, taken in December 1098 amidst stories of desperate crusaders’ cannibalism. In early January 1099, Raymond attempted to assert supreme command by offering to take Godfrey of Bouillon, Robert of Normandy, Robert of Flanders and Tancred into his paid service. Only Tancred, the youngest and poorest of them, seems to have accepted, separating his fortunes from those of his uncle Bohemund, who was intent on staying in Antioch.37 Revival of the crusade’s momentum only came from the mass of crusaders gathered at Ma’arrat al-Numan whose purpose remained fixed on Jerusalem and not on their commanders’ lucrative land grabs in northern Syria. Raymond’s own Provençal followers dismantled the walls of Ma’arrat, leaving the town indefensible and forcing Raymond to accede to their demands to set out to Jerusalem. The rank and file’s suspicions of the leadership, sometimes collectively discussed in formal consultative assemblies, had simmered ever since victory at Antioch; now they determined the course of the campaign.38

Jerusalem 1099

25. Jerusalem from the Mount of Olives, a watercolour by Edward Lear, 1859.

Raymond’s departure from Ma’arrat al-Numan on 13 January 1099 opened the last act of the crusade. Rapid progress south, between mid-February and mid-May, was halted as Raymond, still determined to gain territory of his own, besieged Arqah, fifteen miles inland from the port of Tripoli on the route from the interior of southern Syria to the coast. Once joined by all the other leaders, except Bohemund, Raymond’s strategy collapsed. Godfrey of Bouillon emerged as the spokesman for the mass of disgruntled crusaders, exploiting a new set of visions calling for an immediate assault on Jerusalem. The credibility of the Holy Lance, and by association Raymond who was using it as a talisman, was questioned after its advocate and finder, the Provençal visionary Peter Bartholomew, underwent an ordeal by fire (8 April) from which he died (20 April). Godfrey of Bouillon broke up the siege of Arqah on 13 May. Simultaneously, a Fatimid offer of free access to Jerusalem by unarmed Christians was refused. From Arqah progress was swift, the collapse of negotiations with the Fatimids making speed essential. Following the coast road from Tripoli, shadowed by western fleets, the crusaders encountered minor opposition from Sidon; Tripoli, Beirut and Acre agreed treaties; Tyre, Haifa and Caesarea put up no resistance; Jaffa was abandoned by the Fatimids, who, under the active vizier al-Afdal, had recently reasserted control in Palestine, in 1098 regaining control of Jerusalem from the Ortoqid Turks. At Ramla in early June the crusaders briefly toyed with a direct attack on Egypt. This was rejected. Soon crusade detachments fanned out across the Judean hills. On 6 June, Tancred entered the largely Christian town of Bethlehem where locals overcame initial suspicion in welcoming the crusaders.

4. The siege of Jerusalem, June–July 1099.

The siege of Jerusalem began on 7 June and lasted until a final assault breached the walls on 15 July, leading to a sustained massacre in the hysteria of success, followed three days’ later by a more cold-blooded mass killing, a move prompted by shortage of food and fear of the approaching Fatimid army.39 The Fatimid garrison had clearly counted on relief from Egypt, adopting oddly passive tactics before, seeing the city was lost, quietly surrendering and being allowed to depart. Both sides appeared mindful of events at Antioch, the garrison hoping to sit it out behind Jerusalem’s double walls until rescue appeared, the invaders determined not to be caught in a vice between the city and a relief army.

26. Sicilian twelfth-century reliquary of the True Cross, possibly similar to that of the kingdom of Jerusalem.

The month-long siege of Jerusalem prompted far less epic coverage than the drama of Antioch. Militarily it was very different. Conducted against the threat of the imminent arrival of a Fatimid army, the siege revolved around assault not blockade. The battle-hardened veteran army of a few thousand achieved a remarkable victory accompanied by the now familiar orchestrated religious enthusiasm – visions of divine favour, penitential processions, etcetera – and technical ingenuity – elaborate siege machines built with the help of professional engineers and material cannibalised from Genoese ships. The brutal exultation of success gave way to a final episode of political infighting as the leaders chose Godfrey of Bouillon not Raymond of Toulouse to rule the conquered city. There was no suggestion of handing authority to local Christians, not least because they lacked a suitable political elite. The conquerors quickly imposed their own secular and ecclesiastical hierarchy. A new fragment of the True Cross was usefully discovered that was to serve as the iconic totem of the new regime for the next eight decades. Divine support was immediately called upon, as the still fractious crusade leadership united for one last time to defeat the Fatimid relief army under al-Afdal himself at Ascalon on 12 August. As with the victory over Kerboga at Antioch in 1098, triumph at Ascalon was crowned in the eyes of those reporting it by the seizure of material booty: ‘the treasures of the king of Babylon’ (the crusaders’ name for Egypt): ‘pavilions, with gold and silver and many furnishings, as well as sheep, oxen, horses, mules, camels and asses, corn, wine, flour’.40 This victory marked the end of the First Crusade (see ‘Plunder and Booty’, p. 94).

The improbable success of the First Crusade was a triumph of organisation, determination, morale, improvisation, military leadership and luck. Given its disjointed command structure, the crusade’s achievements appear even more remarkable. Yet the crusaders were quick learners. Following the near-disaster of a split army at Dorylaeum, the feuding, rancorous and competitive leaders thereafter united when confronting sieges, battle or political crisis. Funds were pooled at Nicaea, Antioch and Jerusalem. Bohemund assumed agreed tactical command during the siege of Antioch. The assault on Jerusalem was coordinated. This collective leadership challenged assumptions about optimum command structures while allowing for tensions between leaders and between the leadership and the mass of troops to be aired and defused without the army falling apart. Cut off for long periods from outside help, in constant fear of annihilation, the crusade’s unity came from circumstance: divided they were sure of failure. The leadership’s effective use of targeted spiritual interventions exploited the ideological imperative. The politics of conviction did not exclude the politics of acquisition; one led to the other.

27. First Crusade booty: the Shroud of St Josse, from the abbey of St Josse, Normandy; Persian embroidered silk allegedly brought back by Count Stephen of Blois.

Writing a decade after the Council of Clermont, Abbot Baldric of Bourgueil imagined Urban II offering crusaders ‘the goods of your enemies . . . because you will plunder their treasures’.41 This was hardly a surprising promise. Crusades, like all medieval armies, relied on plunder and booty to incentivise troops and sustain campaigns. Violent foraging, seizure of food when access to markets failed, signalled the transit of notionally friendly regions in central and eastern Europe of the land expeditions during the First, Second and Third Crusades, while shaping the progress and prospects for armies in hostile territory. Every major crusade to the eastern Mediterranean sought re-endowment, by agreement (with Alexius I in 1097 or Tancred of Sicily’s 40,000 gold ounces in 1191), conquest (Thrace by Frederick I in 1190, Cyprus by Richard I in 1191 or Constantinople in 1203–4), coercion (the payment of substantial – 20,000 gold pieces – protection money by Tripoli and Jabala in 1099), or victory in battles or sieges (on the First Crusade alone, at Dorylaeum, Antioch and Ascalon, or at Iconium in 1190). Booty could feed directly to the troops who collected it or indirectly through endowing lords with fresh resources to pay their followers. Division of spoils formed a settled expectation among recruits both before and during campaigns. Formal sharing arrangements featured in agreements between crusaders at Dartmouth in 1147, Richard I and Philip II in 1190, and the crusaders and Venice in 1201. Anxiety, suspicion, competition and resentment over distribution of plunder marked the aftermath of successful operations, for example at Nicaea (1097), Ma’arrat-al-Numan (1099), Lisbon (1147), Acre (1191), Constantinople (1204) or Alcazar (1217). Despite the image and reality of reckless mayhem, and frequent appeals for restraint by commanders, plundering could also be chillingly ordered. Following the Genoese capture of Caesarea in 1101, booty was carefully allocated: the bulk of goods went to the commanders, ships’ captains and ‘men of quality’, with a fifteenth going to the galley crews; the remaining 8,000 troops received 48s of Poitou and two peppercorns each.42 At Constantinople in 1204, after an initial licensed free for all, collection and distribution were centralised. After the capture of Damietta in 1219, allocation was calculated according to status: knights; priests and local recruits; non-noble troops; wives and children.43

28. The most famous crusader booty: the Four Horses of St Mark’s, taken from the Hippodrome, Constantinople, after the Fourth Crusade, 1204.

The importance of booty went beyond necessity, constituting in the minds of contemporaries and participants justified reward. The earliest narrative of the First Crusade combined the spiritual and temporal dividends of steadfast faith and success in recording the crusaders’ supposed morale-boosting battle cry at the battle of Dorylaeum: ‘today if it pleases God you will all be given riches – divites’. These could be massive: Tancred allegedly stripped 7,000 marks worth of silver from Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock alone.44 The diversion of the Fourth Crusade to Constantinople in 1203 was driven, one observer suggested, ‘partly by prayers and partly by reward – precio’.45 This could be taken for almost all crusades, from Palestine to Spain, from German merchants’ profits in Livonia to northern Frenchmen’s freebooting and land-grabbing in Languedoc. Provided the intent was suitably devout, material gain was not seen as a deplorable ambition, even in the original Clermont decree. Doing God’s will, crusaders were free to indulge in legitimate grand larceny, the fruits of force and victory, although their plundering was no more extravagant than that by any other contemporary armies. In inspiration and action, piety and pillage operated in tandem, as on the piratical Venetian crusade of 1122–5 that gained territory for the cross along with brutal plunder and stolen relics for Venice. Crusading treasure seized as booty from the Levant was enthusiastically welcomed home by Genoa between 1099 and 1101, as was Spanish crusade plunder by the citizens of Cologne in 1189. The most obvious and possibly most widely disseminated booty were relics (see ‘Sacred Booty’, p. 252). Temporal swag could include silks, gold, gems, precious rings, arms, military fittings, statuary and other exotic items from the Orient, sometimes – as in Genoa after 1099 or Venice in 1125 and after 1204 – in very large quantities: the plunder from Constantinople has been estimated as more than enough to fund a European state at the time for a decade.46 A Limousin lord, Gouffier of Lastours, was alleged to have befriended a lion during the First Crusade and more reliably to have displayed looted cloth hangings as mementos of his adventure. Fatimid linen, silk and cloth of gold embroideries obtained during the First Crusade, possibly loot from the Egyptian camp at Ascalon, came to be deposited in Cadouin Abbey in Perigord and Apt Cathedral in Provence, transfigured into objects of Christian reverence.47 Alfonso VIII of Castile claimed an Almohad banner after his victory at Las Navas de Tolosa (1212). John of Alluye, a French crusader in the 1240s, returned with a sword made in China, although this, like other souvenirs, may have been a purchase not a battle prize.48 Such trophies enhanced the prestige of the returning hero (John of Alluye’s sword is carved on his funerary gisant, p. 104) as well as offering the chance of being converted into cash or property. The most famous crusade booty were the four horses from the hippodrome at Constantinople displayed from the 1260s on the west front of St Mark’s in Venice. Most plunder possessed more mundane nature and use, providing immediate subsidy for crusaders on campaign, pay for return passages or means to recoup initial capital outlay.49 Crusading could not have functioned without the reality of plunder and booty in a balance of military pragmatism, material attraction and spiritual inspiration that belies easy construction of conflicting motives or an unhistorical dichotomy of the secular versus profane.

Nonetheless, the crusaders’ success owed as much to the incompetence, ill-fortune and divisions of the polyglot city states of the region as to their own resilience. The campaigns of 1097–9 were played out against the regional aftershocks of the Seljuk invasions. Long a politically fractured region, the civil wars in Syria and Iraq following the deaths of Malik Shah and his dominant vizier Nasim al-Mulk in 1092 opened political space for foreign intrusion, an opportunity encouraged by the Fatimids, who initially saw the crusaders as useful allies. A notable feature of the First Crusade was how easily it surfed the shifting currents of regional politics and how quickly its leaders became politically acclimatised. Yet the crusaders’ capture of Jerusalem in 1099 bequeathed a costly legacy. The defence of the Holy City and the Holy Land became a totem of western Christian identity, a culturally defining obsession and an impossible political ambition.

Trophies and Memory

The immediate impact on western Europe came with returning veterans laden with trophies, mementos, plunder, stories and scars: pet lions, luxury linens, loose chippings, lost hands and tall stories.50 Critics were silenced or won over. Survivors rapidly dictated or penned descriptions of the Jerusalem war, which were quickly refashioned by professional monastic writers into more crowd-pleasing literary accounts. Writing a generation later, a monk who had attended the Council of Clermont passed over the events of the crusade because he assumed his audience was already familiar with them through books, secular songs and sacred hymns.51 The memorialising literary genre reached from liturgical songs to monkish chronicles to more overtly secular Latin and vernacular poems, some of epic content and length. Reputations were made (and a few destroyed) by stories of the Jerusalem journey. Old soldiers’ tales were legion, as each area claimed their own particular heroes, such as who was the first man across the walls at Jerusalem: Raimbold Creton from Chartres, who lost a hand, or the brothers Ludolf and Engelbert of Tournai.52 Bohemund helped fashion his own heroic legend during a promotional tour of the west in 1106–7 and earlier when he shipped Kerboga’s tent to his home port of Bari.53 The exotic drew attention to the special status of returned crusaders, such as palm leaves from Jericho or the sensational legend of Gouffier of Lastours’ tame lion, which, after being rescued by Gouffier from a snake, followed him everywhere before drowning in pursuit of his saviour’s departing ship. Gouffier brought back more tangible treasures such as Muslim banners, textiles and rings.54 Families – like Gouffier’s – later played on their links to crusaders by curating and displaying war trophies. Other veterans sought to enshrine their crusade credentials by donating relics acquired on campaign to religious houses. Fame operated reciprocally. Robert of Flanders milked his status as a Jerusalemite in his donations of Holy Land relics and in his charters. Conversely, he and Robert of Normandy were luminously commemorated as crusaders in mid-twelfth-century stained-glass windows at the French royal abbey of St Denis.

30. Commemorating the First Crusade in stained glass at St Denis in the mid-twelfth century.

The rapid memorialisation crossed art forms. Carvings and frescoes in parish churches across western Europe alluded to crusading ideology, its Biblical context or directly to incidents on the campaign, the heavenly intervention of saints at Antioch proving especially popular. The twinned emphases on militant violence and religious conviction, on the agency of devout warriors and the immanence of Christ, were common across visual, aural and literary representations, the victories at Antioch and Jerusalem praised as acts of faith and feats of arms. Such transference could endow secular material objects with numinous quality, as in the case of two famous luxury Egyptian silks woven in the 1090s that survive at Cadouin in the Dordogne and Apt in Provence. The Cadouin silk has been associated from the thirteenth century with Adhemar of Le Puy. Both were perhaps acquired by crusaders either as part of gift exchanges with Fatimid ambassadors or as booty after the battle of Ascalon. While other bits of eastern loot preserved their crusading provenance, these silks were reinvented as sacred icons by the religious communities where they were housed: the Cadouin silk became the shroud of Christ; that of Apt the veil of his grandmother St Anne.55 In some ways such a transformation was appropriate as the crusade powerfully witnessed the physicality of Christian history, a process of literally getting near to Christ and to the events of the Bible, to tread in holy footsteps. Thus were crusaders lastingly transfigured into the new Maccabees and the new Israelites.

31. Shroud of Cadouin.

CRUSADE MEMORIALS

Memory played a prominent role in medieval European culture. This took many forms: commemorative endowments of monasteries, churches and chapels; special liturgies and religious services; written ecclesiastical calendars memorialising events or the deaths of patrons; the collection of letters or creation of literary memory in chronicles, verse or family histories; the conservation of relics of past deeds or their portrayal in statuary, frescoes, mosaics or stained glass; the oral record in family legend, domestic story-telling and public performance, such as sermons. Such memorials promoted crusading and the reputation of crusaders. Past events framed present action and inspired future behaviour. The repeated appeals to the luminous example of the First Crusade, ‘the worthy deeds of our famous ancestors’, resonated for centuries.56 Liturgies and hymns celebrating the conquest of Jerusalem proliferated.57 The circulation of chronicle accounts of past crusades featured prominently in preparations for new enterprises, as did evocations of past triumphs (and disasters) in crusade preaching and propaganda.

Crusade memorialisation assumed concrete forms. Some were ostentatious, such as crusaders’ ceremonial presentation to churches or religious houses of plundered eastern sacred relics, often in lustrous reliquaries, a habit especially noticeable after the First and Fourth Crusades; the secular loot displayed as symbols of dynastic or corporate achievements; the First Crusade Levant textile hangings in the Lastours family museum at Pompadour in the Limousin or the public display of Venetian trophies from Constantinople; or the programme of First Crusade stained-glass windows at the abbey of St Denis in the 1140s.58 More private, if also designed to be seen, were statues, such as that of the returning Lorraine Second Crusade veteran Hugh of Vaudemont at Belval; or the Joinville family epitaph at Clairvaux, composed by the crusader John of Joinville in 1311, which expressly honoured his many crusading ancestors.59 The crusader John of Alluye was buried at the abbey of La Charité-Dieu, near Tours in northern France, around 1248. The monks remembered him in their prayers. His stone effigy conveyed a subtle message commemorating his crusade (1241–4) as it shows him, in full armour, wearing a sword whose elaborate pommel indicates a Chinese origin. At the very least visitors to the abbey might have been impressed by the exoticism of the carving.60

32. Crosses carved on the walls of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

33. Statue commemorating the return of Hugh of Vaudemont from the Second Crusade.

34. The tomb effigy of crusader John of Alluye, c. 1248, showing his Chinese sword.

Generically, the path of the crusader was the path of Christ, the path of the cross, an act self-consciously following the commands to ‘take up the cross’ (Matthew 16:24; Mark 8:34; Luke 9:23) and to ‘do this in remembrance of me’ (Luke 22:19). It was not only the rich for whom these injunctions held power. The less wealthy could participate in memorial ceremonies and liturgies or brag of their exploits with equal vigour and imagination. For concrete memorial, they had fewer options. However, one habit may reflect a common desire to leave a mark: the crosses carved on church walls from the chapel of St Helena beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre to parish churches like that in the English village of Bosham on Chichester Harbour, each testimony to an instinct for recognition and record.