RESHAPING THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN: EGYPT AND THE CRUSADES, 1200–1250

Egypt and the Crusades

‘This is a mighty affair. Great forces have passed thither long ago on various occasions. I will tell you what it is like; it is like a lap dog yapping at a mastiff, who takes little heed of him.’1 The French nobleman and Levant veteran Erard of Valery was attempting to inject a note of realism into discussions in 1274 for a new planned attack on the Mamluk sultanate of Egypt while recognising the thirteenth-century consensus that the key to power in the Levant lay on the Nile.2 Although proving a geopolitical cul-de-sac, appreciation of the importance of Egypt was as old as the crusades themselves. When the armies of the First Crusade arrived in Syria in the winter of 1097–8, they immediately confronted Egypt’s importance and the threat it posed to western conquests in Palestine, negotiating with the Fatimids, each eager to seek common cause against the Seljuks. The thirteenth-century historian ibn al-Athir fancifully suggested the Fatimids had invited the crusaders into Syria for that purpose.3 Crusader-Fatimid discussions only ceased a few weeks before the crusaders advanced into southern Palestine to besiege Fatimid-held Jerusalem in June and July 1099. One veteran recalled the leaders debating whether they should attack Egypt: ‘if through God’s grace we could conquer the kingdom of Egypt, we would not only acquire Jerusalem but also Alexandria, Cairo and many kingdoms’. Against this, it was successfully argued that the expedition lacked sufficient numbers to have any chance of lasting success.4 The importance of Egypt was confirmed when the crusaders had to defend their capture of Jerusalem from a Fatimid relief army. Thereafter, no Latin ruler in Palestine ignored Egypt.

As the Fatimid caliphate crumbled, kings of Jerusalem took advantage with sporadic raids on the Nile Delta. By the 1160s they were extracting regular tributes from a succession of tottering regimes in Cairo. The stakes were of the highest. In 1200, during preparations for the Fourth Crusade, Innocent III admitted the insufficiency of land and population in the Holy Land alone to sustain many artisans and agriculturalists from the west.5 One way out of this bind was to leech onto Egypt’s monetised economy, already being tapped by Italian merchants. Short of conquest, protection money produced gold to pay for troops and defences. This was a game more than one could play. In the 1160s and 1170s the kings of Jerusalem competed directly with Nur al-Din and his Kurdish generals; the ultimate victory of Saladin secured for him precisely what the Latins had hoped for themselves, Egypt’s gold allowing him to reward followers and recruit vast companies of soldiers he then employed to overawe rivals in Syria and encircle the Latin principalities.6 The need to contain, accommodate, coerce or exploit Egypt remained a constant in all western Holy Land strategies.

To recruit for an Egyptian war required a plausible narrative of urgency and obligation: Egypt was not Jerusalem. Sensitivity to criticism of diversion promoted the concealment by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade of the agreement with Venice in 1201 to attack Egypt.7 Crusade propagandists sought rhetorical devices from scripture: in Exodus, the path to the Holy Land had come from the Nile, a precedent Innocent III used in citing the overthrow of Pharaoh before the Fourth Crusade. The Exodus story invited spiritual analogies: Isaiah 31:3: ‘Egypt is man and not God’, the epitome of transient materialism.8 A second rhetorical device placed Egypt in a cosmic setting. Throughout western European media, Cairo and by extension Egypt was known as Babylon, injecting the right note of eternal spiritual conflict into the otherwise severely material business of dealing with a serious political problem. The military challenge was recognised by Richard I during the Palestine war of 1191–2 when, as part of his diplomatic dance with Saladin, he floated a plan in October 1191 to hire (at 50 per cent of cost) a Genoese fleet to ferry his troops to attack the Nile in the summer of 1192.9 The following century saw two major western invasions of Egypt (1218–21 and 1249–50); one aborted effort (1202–4); and earnest diplomacy backed by armed force, as in 1228–9 and 1239–41.

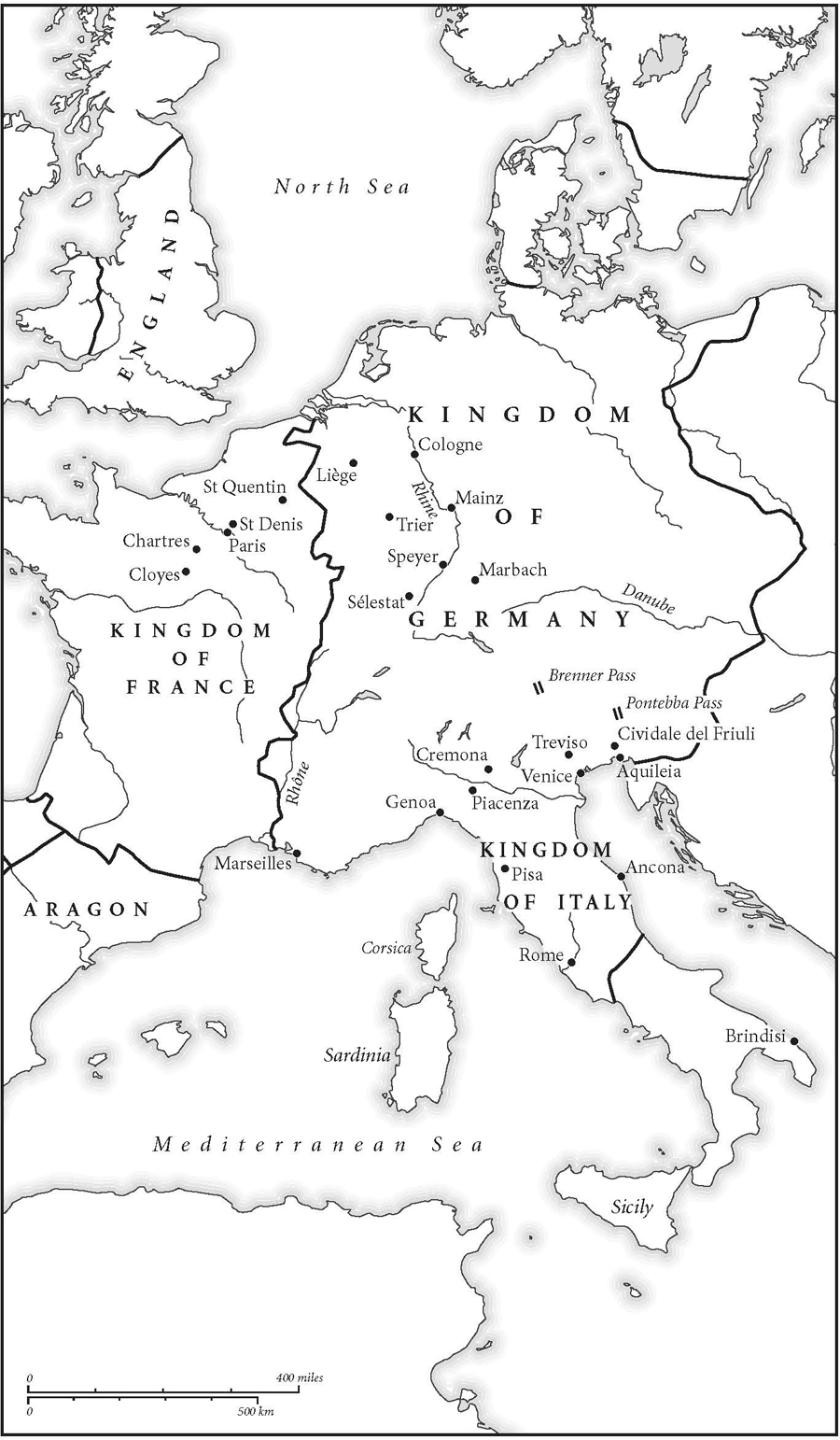

11. Eastern crusades of the thirteenth century.

The first test of the policy came in 1198 when the new pope, Innocent III (1198–1216), summoned a crusade to shore up the gains and restore the losses of the German Crusade. The truce of 1198, set to last until 1204, only covered hostilities in Syria and Palestine, implicitly marking Egypt as a target. Innocent sought first-hand intelligence on the state of the Ayyubid Empire and Sultan al-Adil’s power. Logistics of an invasion had been made easier by the Latin conquest of Cyprus, the western alliance with Cilician Armenia and the recapture of Acre and other Palestinian ports. Innocent attempted unsuccessfully to engage Alexius III of Byzantium in an eastern Mediterranean coalition. The subsequent Venetian involvement in the Fourth Crusade was driven by the prospect of trading privileges in Alexandria and other Egyptian ports where Venice had been overshadowed by competitors such as Genoa. In the event, although the bulk of the Fourth Crusade diverted to Constantinople, where Venice already held the commercial whip-hand, some contingents separately reached Acre and joined a raid on the Nile in 1204.10

Recruitment for Innocent III’s new crusade began despite dynastic rivalries, civil wars and succession disputes in France, England and Germany that prohibited royal participation. Networks of preachers were appointed by the end of 1198, including a prominent charismatic publicist, Fulk of Neuilly. The death of Richard I in April 1199 opened the way for his allies in France, such as the counts of Flanders, Blois and St Pol, to reach accommodation with Philip II. Taking the cross operated as part of the process of reconciliation, binding former enemies to an honourable common enterprise approved by the king. In a coordinated sequence, the cousins, the counts of Blois and Champagne, took the cross at Ecry in November 1199; the pope appointed crusade legates and instituted a clerical income tax of a fortieth to help pay for the expedition in December 1199 (the failure of which cast a financial shadow over the whole enterprise); preaching was authorised from Ireland to Hungary; the count of Flanders, the count of Champagne’s brother-in-law, took the cross in February 1200, followed shortly by the count of St Pol. At meetings in the summer of 1200 at Soissons and Compiègne the sea route east was agreed and ambassadors despatched to Italy to negotiate a shipping contract. With neither Genoa nor Pisa interested, the ambassadors concluded a treaty with Venice in April 1201.

Lothar (1160/1–1216; pope 1198–1216) was the son of the count of Segni, a town south-east of Rome, and nephew of Pope Clement III (1187–91). After studying theology in Paris and canon law at Bologna, Lothar was appointed a cardinal by his uncle in 1190. His early writings show an intense engagement with the image of the cross as a metaphor for the spiritual reality of a Christian life. Although sidelined during the pontificate of the nonagenarian Celestine III (1191–8), he was quickly elected pope on the same day as his predecessor’s death. The election of a thirty-seven-year-old signalled a decisive move away from the line of cautious, usually elderly curial veterans who had tended to be preferred over the previous half-century. Innocent proved to be one of the most dynamic and effective popes of the Middle Ages. His policies revolved around the assertion of papal ecclesiastical and temporal rights and spiritual authority; the development of church reform through the evangelisation of the laity and the exercise of canon law; and the material protection of the faith against heretics and infidels. In the scope, detail and success of advocacy and development of the crusade, Innocent proved to be the most significant pope after Urban II. Innocent’s marriage of theological clarity to institutional frameworks established the character of official crusading for following generations.

75. Innocent III.

While in general terms more of a codifier than an absolute innovator, Innocent clarified the nature of the crusade indulgence to include remission of sins not just penance; instituted crusade taxation of the clergy (in 1215, after an aborted attempt in 1199); organised comprehensive papal licensing of regional crusade preaching across western Christendom (1198); proposed proportionate indulgences according to contributions below actual service (an idea canvassed as early as 1157 by Hadrian IV); and offered redemptions of crusade vows to any who wished to take the cross but were unable to fulfil their vows in action (1213, building on an idea of Clement III). Vow redemptions, clerical taxes and donations transformed crusade finance. From Innocent’s reign regular special prayers and processions for the crusade became familiar across western Europe, as did the appearance of chests in local churches to receive alms and donations. More indirectly, his sponsorship of the early Dominican and Franciscan friars presaged their later rise to dominate crusade preaching. The great crusade decrees Quia Maior (1213) and Ad Liberandam (1215) provided lasting rhetorical and administrative templates. Innocent extended crusade privileges to political conflicts in southern Italy and Sicily (1199); to campaigns against Languedoc heretics (1208–9), Spanish Moors (1212) and, partially, to the Baltic. The Fourth Lateran Council (1215) provided the cornerstone of Innocent’s policies. Summoned to confront reform, heresy and the crusade, the council approved the instruments as well as principles in support of Innocent’s embracive concept of evangelising the laity through offering sacramental, penitential and physical protection in a Christendom directed by the Church and united under papal authority. The crusade combined Innocent’s core message of penance, redemption and active obligations demanded by Christ of all the faithful. Beyond political, polemical and administrative skills, Innocent was no armchair organiser. After losing control of the Fourth Crusade, he ensured close papal involvement in the Fifth, engaging in active proselytising. A seasoned preacher in Latin and the Italian vernacular, not afraid to extemporise, his sudden death in July 1216 may well have been hastened by his exhausting public preaching tour for his new eastern crusade.

The Venetian treaty, for all its later infamy, displayed understanding of what an invasion of Egypt required. For 85,000 marks, payable in four instalments from August 1201 to April 1202, the Venetians contracted to supply ships, including specialist horse-carrying huissiers, for an army of 4,500 knights, with horses, 9,000 squires and 20,000 infantry, along with provisions for men and beasts for up to a year. The Venetians would additionally contribute a fleet of fifty galleys at their own expense, as well as the crews for the crusader ships, who could have numbered as many as 30,000. This great armada, after mustering at Venice on 29 June 1202, was to sail directly to Egypt, avoiding breaking the 1198 Syrian truce. The scale of the enterprise matched the ambition. To fulfil the Venetians’ contractual obligation to build, equip and man the fleet, Doge Enrico Dandolo imposed a moratorium on all other commercial activity.11 While the cost per head was in tune with previous shipping contracts, such as Philip II’s with Genoa in 1190, the Venetian deal assumed not only the deep pockets of the crusade leaders but also that large numbers of those not directly attached to them would take advantage of the transport on offer. The former assumption may not have been too fanciful. Count Theobald of Champagne, the leading protagonist of the crusade in northern France before his early death in May 1201, budgeted for 50,000 marks to pay for his own and hired troops. It was the failure of sufficient numbers of independent crusaders to arrive in Venice in 1202 that scuppered the Venetian deal, threatening the whole enterprise. While the northern French core of the leadership remained robustly committed to the Venetian deal, and publicised the muster widely across France and Germany, thousands of recruits sought other more convenient ports. Even some followers of the counts of Flanders and Blois used southern Italian ports rather than Venice, while a Flemish fleet partly sponsored by Count Baldwin made its own way to the Holy Land.12 The pope recognised this lack of unanimity by sending one legate to Venice and the other to Acre.

The preaching campaign followed previous patterns with local clerics and the Cistercians featuring prominently. Centred on Flanders, Champagne, the Ile de France and the Loire valley, recruitment extended from the British Isles to Italy, from Saxony to Provence. Fulk of Neuilly’s preaching became notorious, both for its powerful effect and its ignominious end when he was accused of embezzlement of the alms he had collected.13 The geographic breadth and moral force of the preaching campaign cut across political divisions. On the death of Theobald of Champagne in 1201, the French leaders chose as their nominal commander the well-connected northern Italian Boniface, marquis of Montferrat, from a family with extensive previous associations with Byzantium and the Holy Land as well as Germany, where Boniface’s cousin, Duke Philip of Swabia, was a claimant to the throne.

76. Venice.

Perhaps between 12,000 and 15,000 troops arrived at Venice during the summer of 1202. Although comparable with the largest crusader hosts, this fell far short of the numbers envisaged in the 1201 treaty, leaving the crusade leaders scrabbling to fulfil the financial terms. Despite a levy on every crusader at Venice, the leaders’ personal funds and heavy borrowing, 34,000 marks remained outstanding, 40 per cent of the agreed price, presenting the crusaders and Venetians with the mutually unpalatable prospect of abandoning the expedition and the waste of an extremely powerful armed and mobile fighting force. To save a return on their great investment, the Venetians proposed a moratorium on the debt. This would now be repaid from profits on future conquests, beginning with the Dalmatian port of Zara (Zadar), despite it being a Christian city under the protection of the king of Hungary, who in 1202 happened to be a crucesignatus. The attack on Egypt was postponed to 1203. In return, the doge committed himself and the city more firmly to the crusade as active allies and participants, not just shippers. Although acknowledged as inappropriate, the Zara plan was accepted by the leadership, including the papal legate Peter of Capuano, as the only way of continuing the crusade. The high command showed their queasiness at the whole business by keeping most crusaders in the dark even after the fleet left Venice in early October 1202. The pope was less easily deflected; he sent letters prohibiting the attack and threatening all who took part with excommunication.

The goal of Egypt remained. The intensity with which the high command faced down papal objections and dissidents within their own ranks uneasy at fighting fellow Christians rested on the understanding that only such a large force had any chance of making an impact on Ayyubid power and so needed to be kept in being by agreeing to Venetian terms. This appreciation of the costs of the military requirements explains the attraction of the offer made by Alexius Angelus, nephew of Alexius III, son of the deposed Isaac II Angelus and claimant to the Greek throne. Backed by his brother-in-law, Philip of Swabia, and Boniface of Montferrat, Alexius attached himself to the crusade army at Zara in December 1202, promising, in return for being placed on the Byzantine throne, to assist the crusade with 10,000 Greek troops and 200,000 marks for the invasion of Egypt.14 Despite offering a reunion of the Greek Church with Rome, Alexius had failed to secure the support of Innocent III, who still hoped for a rapprochement with Alexius III. Yet through the good offices of Boniface and later Doge Dandolo, Alexius presented the crusaders with an apparently alluring opportunity to gain Byzantine support and re-endow the crusade.

A SPRING DAY IN BASEL, 1201

During the spring of 1201 news of the fresh expedition to recover Jerusalem and rescue the Holy Land continued to circulate in the valley of the Upper Rhine in south-western Germany. In the city of Basel (now in north-west Switzerland) the year before, in May 1200, the city’s bishop had taken the cross with a number of local abbots and monks, a gesture of ecclesiastical solidarity that appeared to lead to no immediate concerted general effort of promotion. By contrast, a year later, advance notice had prepared an expectant crowd of clergy and laity to gather in the cathedral, dedicated to the Virgin Mary but known locally as the Münster, then probably still a building site as the church was being restored after a devastating fire in 1185. The physical renewal and restoration provided an appropriate image and setting for what they had come to hear: the cross being preached by Abbot Martin of the Cistercian abbey of Pairis in Alsace, one of the local clerics authorised by Pope Innocent III to preach the cross in the diocese of Basel. The sermon had evidently been well publicised, the monk of Pairis who recorded the event a few years later noting that the large crowd, ‘prepared in their hearts to enlist in Christ’s camp, were hungrily anticipating an exhortation of this sort’. When Abbot Martin stood up in Basel cathedral that spring day he was preaching to the choir. As with modern evangelism, crusade promotion was carefully planned with advance publicity ensuring good attendance at its functions.

Martin’s sermon operated as a focus in a series of ritualised responses. Rumours of the crusade and Martin’s arrival created a fraught atmosphere of expectation and aspiration, tensions released during and after the sermon through emotional gestures: weeping, groaning, sighing and sobbing, emotionalism encouraged by the preacher who led the lachrymose histrionics. The sermon itself, recorded as a literary performance evoking the Cistercian tradition of crusade evangelism and clearly modelled on Bernard of Clairvaux’s preaching, crystallised the papal appeal to Christians to acknowledge the transcendent redemptive importance of the Holy Land and their warriors’ duty to ‘hasten to help Christ’, encouraged by the glorious crusading past, the prospect of future reconquest, and the bargain of spiritual and temporal gain, the latter quite explicit: ‘in the matter if the kingdom of heaven, there is an unconditional pledge; in the matter of temporal prosperity, a better than average hope’. The whole show was completed by the abbot giving out crosses and promising to join the crusade. The account of Martin’s sermon that spring day in Basel introduces a laudatory narrative of the abbot recruiting a regional contingent in which he takes a leading role on campaign, the story culminating in justifying his act of grand larceny during the sack of Constantinople when he and his chaplain filled their habits with over fifty looted relics from those of the Passion, Christ’s life, body parts of John the Baptist and the Apostles, to pieces of lesser saints such as the seventh-century Merovingian abbess Adelgonde or Agricius, the fourth-century first bishop of Trier. The relics were carried back by Martin to adorn his monastery of Pairis. His day in Basel formed just one act in this drama, but, in formal literary remembrance at least, it incorporated elements familiar across western Christendom at the opening of the thirteenth century: papal authority and influence over the promotional process; the central recruiting themes of Christian obligation, the urgent plight of the Holy Land, the importance of past glories, the unambiguous offer of spiritual and material profit. The crowds assembled in Basel Münster knew what they were there for and expected the performance Abbot Martin delivered, all concerned playing their choreographed parts in the cause of the cross. In fact, Martin may not have been at all remarkable; even fellow Cistercians who wrote of the Fourth Crusade never mention him.16

77. The Münster, Basel, site of Abbot Martin’s sermon.

The seizure of Zara in November 1202 fitted a pattern of plundering familiar from both the First and Third Crusades, the latter’s predation on Sicily and Cyprus showing that violence against Christians in pursuit of funds and provisions was not the novel prerogative of the Fourth Crusade. As Count Hugh of St Pol later explained, without more funds to pay for soldiers and materiel, the goal of Jerusalem was impossible.15 Nonetheless, the capture of Zara threatened to end the campaign, exciting vocal opposition within the army – ‘I have not come here to destroy Christians,’ said one dissenter17 – and a papal letter excommunicating any who took part. The letter was suppressed by the leadership in deft information management. Subsequently, faced with disbanding the crusade or tolerating its insubordination, Pope Innocent tacitly acceded to allowing the crusaders to avoid excommunication while travelling on the ships of the still-excommunicated Venetians. Even Innocent’s prohibition on further attacks on Christians was qualified in cases of obstruction or necessity.18 Disquiet over Alexius’s plan persisted over the winter of 1202–3 at Zara and the following April when the fleet moved on to Corfu. While many deserted, the need for re-endowing carried the day. The Venetian-crusader fleet sailed on to Constantinople, which was reached, without any effective local resistance, on 24 June 1203.

The Greek failure to contest the crusaders’ passage through the Hellespont provided a mixed augury. Weak Byzantine defences – apparently the Greek emperor had only twenty ‘rotting and worm-eaten small skiffs’ at his disposal19 – suggested a decayed fiscal and administrative regime, hardly a solid basis for the promised lavish aid. However, Greek land forces, chiefly paid foreign troops, provided consistently stiff opposition in a series of encounters in and around Constantinople between June 1203 and April 1204. It is tempting to see the events of 1203–4 as a dual culmination: of long-standing hostility to devious, aloof and schismatic Byzantium; and of prolonged decline in Greek imperial power. Neither is fully justified. Each large crusade army that passed through Byzantium had encountered supply difficulties and diplomatic tensions, yet suggestions for conquest had repeatedly been rejected. By contrast, the 1203 crusaders’ initial intervention was framed as a restoration of a legitimate heir who would then support the crusade and reunite the Greek Church with Rome. This differed from the sustained territorial ambitions of the Norman Sicilian rulers in the Balkans and Greece such as had led to the brief capture of Thessalonika in 1185. For many interested powers in the west, including the papacy, Byzantium was still seen as a potential, if awkwardly inscrutable, ally, enmity revolving around shifting political advantage not fundamental alienation. Religion and commerce bound as much as they divided. Even the often fraught Byzantine–Venetian relationship had been eased with Greek payment of reparations for attacks in 1182 on the Venetian community in Constantinople and the restoration of Venetian trading privileges. Byzantine imperial power had appeared impressive until dynastic feuding in the 1180s loosened central grip, so that by 1203 islands and provinces had begun to assume increased autonomy, a process the crusaders’ conquest of the capital in 1204 did nothing to reverse.

78. Constantinople in the fifteenth century.

The diversion to Constantinople was regarded by the crusaders as a means of keeping alive prospects of campaigning in the Levant. For the Venetians it offered an opportunity to further recoup their massive capital outlay; consolidate existing trading rights; and sustain the hope of breaking into the even more lucrative Egyptian market. However, immediately on arrival at Constantinople, westerners’ expectations were confounded. Far from being welcomed as a liberator or returning hero, young Alexius was greeted with armed resistance. Even after his assumption of power following the crusaders’ assault on the city in July 1203 and the flight of Alexius III, Alexius, now Alexius IV, attracted sullen Greek acceptance at best, a political situation further complicated by the unscheduled emergence from prison and restoration of the blinded Isaac II, who then ruled dysfunctionally with his son. To sustain his position, Alexius IV agreed new contracts with the crusaders securing their help for another year in return for more guarantees of assistance for a future Levant campaign. To pay for the deal, Alexius stripped Constantinople of treasure, consolidating Greek hostility to the foreigners and further isolating himself. The presence of the crusaders, camped at Galata across the Golden Horn from the city, with their demands on food supplies, added to the febrile atmosphere as winter closed in. With the Venetian fleet and crusaders’ camp coming under attack from Greek dissidents, a confused series of palace coups ended in February 1204 with Alexius IV and his father dead and a new emperor, an anti-westerner, Alexius V, committed to destroy the crusaders.

Their deteriorating position left the crusaders few options. As one account recalled, ‘they were neither able to enter the sea without danger of imminent death nor delay longer on land because of their impending exhaustion of food and supplies’.20 Without supplies, money or seaworthy ships, their only escape lay through the city. Lingering doubts over attacking fellow Christians were allayed by clergy insisting that combating schismatics, regicides and oath-breakers who were impeding the cause of the Holy Land was both legitimate and meritorious, earning indulgences for those who died in the fighting.21 The crusaders would take by force what the Byzantines had failed or refused to provide under treaty or alliance. In March 1204 the crusaders and Venetians agreed a new contract that settled the distribution of booty from the city, including the final settlement of the original crusader debt, and set the arrangements for carving up power within the Byzantine Empire once the city had fallen. The crusaders agreed to delay their departure east for yet another year, to March 1205, deferring the Egyptian campaign for the fourth time since 1202. The plan was a desperate throw; no foreign army had captured Constantinople since its foundation nine centuries before.

The final attack began on 9 April 1204. In the ensuing capture and sack of the city between 12 and 15 April the crusaders killed thousands of civilians, desecrated churches, destroyed buildings, and looted the city of the moveable wealth that had survived the fiscal predations of Alexius IV and a devastating fire the previous August. The sack of Constantinople was calculated and controlled after the first day of mayhem, the plundering systematic. It was not in the conquerors’ interests to allow unbridled destruction of what was to become their new capital. It has been estimated that the total value of the plunder, in addition to 10,000 horses, may have been around 800,000 marks, enough to fund a substantial western European state for over a decade.22 On top of this were boatloads of relics stolen not exclusively but chiefly by clerics – ‘holy robbers’23 – for whom such sacred loot constituted investment in their home churches’ future prosperity (see ‘Sacred Booty’, p. 250). The gluttonous sack of Constantinople, while not outside the brutal military conventions of the time, struck contemporaries from ibn al-Athir in Mosul to Innocent III in Rome, no less than Byzantines and later observers, as an atrocity in its scale of rapine, slaughter and wanton destruction of centuries of classical and Christian civilisation.24

The capture of Constantinople did not end the Fourth Crusade. Baldwin of Flanders, chosen by the conquerors as the new emperor, insisted at his coronation that the relief of the Holy Land remained the objective for the following year. Only after defeats in 1205 at the hands of Bulgarians and Greeks did the papal legate unilaterally absolve the crusaders in Greece of their Holy Land vows, to the unrestrained but impotent fury of Innocent III. However, not all crusaders had joined the Constantinople excursion or travelled east via Venice. Substantial contingents, including the large Flemish fleet with Countess Marie of Flanders on board, sailed directly to Acre, perhaps up to a fifth of those nobles who took the cross in 1199–1200, with as many as 300 knights reaching the Holy Land, in comparison with the 500 to 700 knights at the Byzantine capital.25 These Holy Land crusaders joined King Aimery of Jerusalem in raids into Galilee and to the Jordan, as well as a naval sortie in May 1204 to the Nile Delta port of Fuwa, which they briefly occupied and ransacked. This aggression encouraged al-Adil to reach a six-year truce favourable to the Franks.

While meagre in its impact on the Levant, the Fourth Crusade exerted a profound influence on future crusading. The schism with the Greek Church was rendered unbridgeable except as a paper diplomatic convenience. Consequent rule over parts of the Balkans, Greece and the Greek islands accelerated direct western investment and exploitation of the region that lasted into the early modern period. Yet western immigration remained a minority concern, initially largely confined to networks of northern French noble houses and the Venetians. The occupation of Latin Greece – or Romania as it was known in the west – hardly deflected support for the remaining outposts of Outremer. Attempts to harness crusades to defend Latin Greece met lukewarm responses from the 1230s and did not materially deprive the Holy Land of aid. More widely, the scale of planning and resources needed for any Egyptian enterprise had been clearly demonstrated.

Invasions: The Fifth Crusade, 1217–21

The Fourth Crusade prompted a refashioning of funding and administration when Innocent III launched a new mass eastern crusade in 1213. The bull Quia Maior offered the crusade remissio peccatorum, remission of sins, to anyone who contributed by personal service, proxy, subsidy or other material assistance. At the same time, overturning the official line adopted since Urban II, there was to be no restriction or test of suitability on who could take the cross, with the vow now able to be commuted, redeemed or deferred.26 Formally systematised by Gregory IX in 1234, this policy gave non-combatants – including the old, young, infirm, aged, and weak, men and women – and those of modest means access to the crusade’s uniquely comprehensive spiritual privilege, extending its social range while, through cash redemptions of vows, widening the source of funds. This spiritual largesse was supported by licensed regional teams of preachers, often led by University of Paris-trained theologians, keeping in direct contact with the papal curia. Congregations were encouraged to donate alms, bequeath legacies, and join in special prayers and processions. Chests for crusade funds were placed in parish churches across western Europe. Building on precedent, by further institutionalising crusade processions, prayers, vow redemptions, alms and legacies, Innocent III sought to embed crusading in the Catholic culture of the west. More directly, the pope raised taxes. The Fourth Crusade had demonstrated the consequences of the failure of his 1199 tax scheme. Now, Innocent deliberately secured the explicit assent of the assembled clerical representatives at the Fourth Lateran General Council of the Church in 1215 to an ecclesiastical income tax of a twentieth, a model for papal crusade taxes for another century and a quarter (the last such general tax was authorised in 1333) and a fiscal precedent for the rest of the Middle Ages.

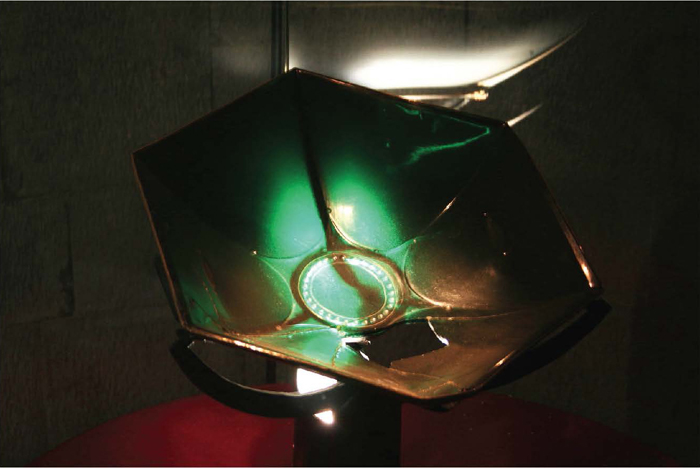

Veneration of relics defined the spiritual mentality of medieval Christendom and nowhere more obviously than in the crusades. For believers, relics provided intimate tangible contact between the present and the eternal, proof of the living truth of the Gospel promise of salvation (the common medieval word for relic, pignus, also meant a pledge). Crusading’s initial inspiration focused on the repossession of the most numinous relic of all, the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem regarded as a liminal space between earth and heaven, the terrestrial and the transcendent. The Holy Land provided the unique repository of physical remains of the Apostles and material witness to the life of Christ, the places He visited, the objects He touched, the Passion and especially the True Cross. As the setting of the early Church, the scene of miracles and martyrdoms, the whole of the eastern Mediterranean provided fertile ground for relic hunters. Just as pilgrims had done before, crusaders were avid collectors, by purchase, gift, theft, plunder or discovery. The excavation of the supposed Holy Lance briefly and vitally transformed the crusaders’ morale at Antioch in 1098, while the convenient unearthing of a fragment of the True Cross at Jerusalem the following year provided the new Frankish settlement with its most iconic totem. The range of relics transported westwards is indicated by a fairly representative list of items brought back from Palestine and given to Gascon monasteries in the 1150s: splinters of the True Cross; Christ’s blood mixed with earth; pieces of Christ’s cradle, the Virgin Mary’s tomb and the rock where Christ prayed at Gethsemane; hairs of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalen; and a miscellany of mementos of scriptural events and characters: the Apostles, John the Baptist, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Stephen Protomartyr.27 Following their supposed role at Antioch in 1098, eastern martial saints were increasingly popular: Robert of Flanders brought back St George’s arm and a portion of ribcage in 1099.28 All had been authenticated by reputable Holy Land donors, who may have turned tidy profits on such transactions. Certainly the supply seemed limitless. The continuous flood of relics carried back to western Europe by crusaders and pilgrims served many purposes: securing mutually beneficial patronage links between monasteries and patrons; enhancing the attraction of abbeys that housed the new holy objects as lucrative pilgrimage sites; promoting an internationalisation of scriptural and Holy Land saints’ cults; gilding the reputation and securing the memory of those who had brought them. Through acquisition in the east on crusade, even obviously secular objects, such as luxury textiles, gems or military equipment, could acquire quasi-spiritual significance when presented as gifts to shrines and religious houses. Some, such as the Fatimid silks at Apt and Cadouin (see p. 101) or the Sacro Catino in Genoa (a Roman basin of Egyptian emerald glass looted from Caesarea in 1101), became rebranded as actual relics themselves.29

79. The Sacro Catino, Cathedral of San Lorenzo, Genoa, acquired from Caesarea in 1101.

80. Byzantine loot: the Archangel Michael, St Mark’s, Venice.

While relic-gathering was integral to the expectations and experience of all eastern crusading, nothing compared with the orgy of theft by ‘holy robbers’ at Constantinople, Christendom’s greatest depository of holy detritus, after its capture by the Fourth Crusade in 1204.30 In the mayhem following the city’s fall, crusading clergy and laymen alike systematically scoured the churches and monasteries of the Byzantine capital in search of relics to transport home to glorify their own or a local church. Using trickery, bullying and force, some, like the bishops of Soissons and Halberstadt and the abbot of Pairis in Alsace, made off with cartloads of relics and reliquaries, as well as gold, silver, gems, silks and tapestries to decorate their new shrines, to be welcomed as miraculous benefactors when they returned home with their loot, ‘triumphal spoils of holy plunder’.31 Laymen were equally eager: the great Burgundian monastery of Cluny acquired the head of St Clement thanks to the burgling skills of a local noble crusader, Dalmas of Sercy.32 The knightly chronicler Robert of Clari donated his probably purloined relics of the Passion to the monastery of St Pierre, Corbie. The trade did not stop in 1204. One calculation identified over 300 individual objects that reached western Europe taken between 1205 and 1215, with forty-six feasts instituted to commemorate the arrival of new relics in the west.33 The benefits were clear, in new foci for miracles, a quickening of the pilgrim trade and the consequent rise in some ecclesiastical incomes, and hence increased investment in buildings and local infrastructure. The fortune of the previously struggling monastery at Bromholm in Norfolk was made thanks to the arrival in 1205 of a piece of the True Cross stolen from Constantinople. However, this sacred contraband created a glut on the market that highlighted the problem of duplicates and fakes. Relics were often subject to scrutiny of their authenticity, none more famously than the Holy Lance of Antioch during the First Crusade (a trial by fire proving inconclusive but seriously undermining its reputation). After 1204, the issue became so acute that the Fourth Lateran General Council of the Church in 1215 imposed a papal licensing system for all newly venerated relics to protect the faithful from ‘lying stories or false documents as has commonly happened in many places on account of the desire for profit’.34 The need for authentication led to a trade in provenances in Constantinople and a slew of simultaneously celebratory and exculpatory narratives of the Fourth Crusade designed to validate legitimacy of both relic and ownership, the latter often no less dubious than the former. However, despite the queasiness of some authorities, the centrality of relics persisted. Crusade preachers regularly used splinters of the True Cross as props, while Louis IX of France integrated his possession of Passion relics, especially the Crown of Thorns acquired from Constantinople via the Venetians, into his vision of sacral kingship and promotion of the crusade. After his canonisation in 1297, in a sort of sacred relay, his cult generated relics of its own.35

The promotional campaign emphasised the crusade as a metaphor and exemplar for the Christian life. Innocent’s enthusiasm for the crusade’s fusion of religious commitment and political action, while, as Quia Maior made clear, never losing sight of the primacy of the Holy Land as an objective, prompted the application of crusade formulae – cross, indulgence, privileges, prayers, processions, etc. – in various configurations to other arenas: against enemies of the papacy in Italy and Sicily; heretics in Languedoc; Muslim rulers in Spain and pagans in the Baltic. Such were the pope’s predilections that petitioners actively sought the perceived benefits of crusade institutions for their own local battles, as did the bishop of Riga in the eastern Baltic in 1215. Victims, such as the Languedoc counts in 1215, facing a crusade against alleged heresy in their lands, argued equally vigorously for their cancellation.36 Innocent III permanently influenced how future crusades were conducted and the ways in which crusading permeated western European society. His policies came close to establishing a near-permanent crusade by disseminating a sense of existential crisis, depicting Christendom beset by enemies: Turks in the east; Moors to the south; pagans in the north; and, no less toxic, within Christendom itself, heretics and dissenters. Popular mood was focused by the increased presence of preachers broadcasting messages of threat supported by the communal ritual of prayers and intercessory processions. The effectiveness of this programme received unexpected proof. In 1212 the failure of the Fourth Crusade, the dissemination of news of the dire threats to the faith and preachers’ rhetorical revivalist emphasis on the sanctity of Apostolic poverty provoked demonstrations and marches in northern France and the Rhineland later configured as the Children’s Crusade (see ‘The Children’s Crusade’, p. 258).37 Such awareness from those on the fringes of social power – the young, the rootless, the economically marginalised – revealed the reach of Innocent III’s proselytising.

The new eastern crusade was intended as the most coherent yet. The well-attended Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 was framed by the call to the Holy Land crusade, part of an agenda including pastoral reform and the fight against heresy. At the council, the crusade led a programme of lay evangelisation including decrees establishing the doctrine of Real Presence of Christ’s Body and Blood in the eucharist and the requirement for annual oral confession, both sacramental measures involving access to God’s grace and salvation paralleled in the penitential commitment of crusading. The council confirmed the crusade preliminaries, with a few modifications, and fixed the time and place of the muster (Messina or Bari, 1 June 1217) and Egypt as the destination. Details, including bans on tournaments and trade with the enemy, were collected in the decree Ad Liberandam, which was to serve as a model for later crusades. The programme of preaching and recruitment initiated, in some regions, a decade-long engagement with the eastern crusade, only ending with the controversial expedition of the excommunicated Frederick II of Germany and Sicily in 1228–9. This commitment sustained through three pontificates (Innocent III, who died in 1216; Honorius III, 1216–27; and Gregory IX, 1227–41) confirmed crusading as a familiar and regular rather than exceptional feature of devotional life and politics, a process enhanced by parallel crusading ventures in the north-eastern Baltic (against pagan natives) and Languedoc (against heretics).

Recruitment demonstrated the continued popularity of eastern crusading, although, unusually, this did not include the kingdom of France, due to war with the king of England, the distraction of the Languedoc crusade, and the unpopularity of the papal legate, Robert Courson. In Germany, England and the cities of northern Italy, all regions of civil war and festering political rivalries, the crusade, as a neutral higher calling, provided context for conflict resolution. Details of recruitment, surviving in greater quantity than for previous expeditions, show the mobilisation of all sections of free society, women as well as men.38 As before, contingents revolved around traditional lordship and communal hierarchies. However, the scale of recruitment, combined with the absence of clearly established overall leadership, produced an uncoordinated muster. With sea travel now the only practicable means of transporting large armies, by the summer of 1217 two substantial coalitions gathered at opposite ends of Europe, one led by King Andrew of Hungary and Duke Leopold VI of Austria in the Adriatic, and the other, from Frisia, the Low Countries and the Rhineland, in the North Sea. Neither coalition stayed united. The Germans and Hungarians arrived separately at Acre in the late summer and autumn of 1217, to be followed the next spring by the northern Europeans, who had wintered severally in Iberia or Italy by which time Andrew of Hungary had already departed overland for home (January 1218). Staggered arrivals and departures became prominent features. The fluid rules for taking the cross and preachers’ tone of easy spiritual reward seem to have encouraged vow fulfilment based on personal contribution rather than strategic completion. Philip II in 1191 provided a precedent, while the short-term commitments of the Albigensian crusaders and the annual campaigners under the cross in Livonia offered immediate models.

THE CHILDREN’S CRUSADE

Popular engagement with the crusade found exceptional expression in the spring and summer of 1212 when crowds of enthusiasts in the Low Countries, the Rhineland and parts of northern France gathered in marches proclaiming devotion to the cause of the liberation of the Holy Land and return of the True Cross. Conditioned by a generation of blanket crusade evangelism, these demonstrations took the form of mendicant penitential processions, probably stimulated by Innocent III’s institution of liturgical processions to solicit divine aid to counter Almohad advances in Spain in 1211 and the intense preaching campaign on behalf of the Albigensian Crusade in 1211–12. The deliberate promotion of an urgent sense of Christendom in crisis, coupled with preachers’ persistent emphasis on the virtues of apostolic poverty, moral purity and the redemptive power of the cross, served to draw attention both to the failures of the elite-led expeditions to the east and the consequent frustrations of those prevented from participating in the crusade and its benefits by virtue of their marginal social and economic status.

The narrative of what happened in 1212 is impossible to determine with any certainty. Chronicle accounts cannot be reconciled, reflecting individual attempts to organise memories of events that appeared startling, eccentric and potentially unnervingly disruptive, from the start encouraging myths, morality tales and tall stories. What emerges is a picture of two centres of action. One in western Germany, focusing on traditional urban as well as rural centres of crusade recruitment, including Metz, Cologne and Speyer, appeared overtly directed towards the crusade to the Holy Land, with stories of massed processions from March to July, a leader called Nicholas carrying a tau cross, and of contingents carrying pilgrim insignia crossing the Alps into Italy and, largely vainly, seeking ships to the Levant. In the other area of agitation, in the Dunois, Chartrain and Ile de France south-west of Paris, the emphasis as recorded appeared more generally revivalist, although those marchers who converged on the abbey of St Denis near Paris for the annual Lendit Fair in June, apparently carried crosses and banners and chanted for the restoration of the True Cross. These were led, in some accounts, by a shepherd, Stephen of Cloyes, near Vendôme, a symbolically significant profession in populist religious fundamentalism. Direct association between these two contemporary movements may have been real, accidental, coincidental, non-existent, imaginary or merely literary.

81. Modern myth images: the Children’s Crusade in the Rhineland by Gustave Doré, 1877.

The intriguing element that has attracted subsequent attention came from descriptions of participants as pueri, literally ‘children’, but more likely indicating the powerless and rootless. Descriptions identify those involved as being on the fringes of the settled social hierarchy: youths, including girls; adolescents; the unmarried; the old; shepherds; carters, ploughmen, farm labourers, artisans. Whether any reached Palestine is doubtful, although there were stories of some ‘crusaders’ finding employment in Languedoc and one writer placed Nicholas at Damietta on the Fifth Crusade. But such accounts fit moral not historical narratives. Nonetheless, the uprisings of 1212 reveal an extensive social engagement with crusading, providing strong testimony to the cultural penetration of crusading as a social and religious ambition; to the effectiveness of sustained preaching in stirring popular response; and to the existence of political awareness and agency among groups ostensibly far removed from traditional political elites. The issues raised by the 1212 demonstrators – moral reform, the threats to Christendom, the redemptive power of the cross – precisely fitted papal policy, even though there is no mention of these events in surviving papal records. The 1212 marchers exposed the dynamic popular appeal of crusading later illustrated in the so-called Shepherds’ Crusades of 1251 and 1320 in France. They may also have exerted significant influence on the future direction of the crusade project. Faced by this potentially disruptive combination of popular enthusiasm with frustration at being excluded from the institutional apparatus and benefits of crusading, a year later, in his bull Quia Maior of 1213, Innocent III proposed a system of vow redemptions so that, regardless of military suitability, anyone could take the cross and enjoy crusade spiritual privileges while contributing whatever they could afford. This could thereby offer at least partial opportunity for direct general public involvement, a measure that at once recognised mass aspirations while simultaneously seeking to contain their expression.39

12. Places associated with the Children’s Crusade.

82. A crusading bishop’s mitre – that of James of Vitry.

The early arrivals helped secure the environs of Acre and its food supplies, culminating in the fortification of the Athlit promontory twenty-five miles to the south, necessary preliminaries to an attack on Egypt.40 An alliance with the Seljuks of Iconium served to further protect the Outremer enclave. Once the northern European fleets had assembled at Acre, the only question for the crusaders and the king-regent of Jerusalem, John of Brienne (1210–25), widower of Queen regnant Mary (1205–12) and father of Queen Isabel II (1212–28), was which Egyptian port should be attacked. The choice fell on Damietta, at the head of the main eastern estuary of the Nile, already the target of a Byzantine-Frankish assault in 1169 and, unlike Alexandria, without a large western commercial presence. The combined crusader and Outremer fleet arrived off Damietta in late May 1217, the opening of a gruelling two-year siege that stretched the invaders’ logistics, technological ingenuity and morale to their limits. Internal divisions within the Ayyubid regime surrounding the death of Sultan al-Adil in August 1218, and the rocky succession of his son al-Kamil, failed to weaken Egyptian resistance, while the regular bi-annual reinforcement and departure of crusaders undermined their strategic focus and campaign camaraderie.

This was matched by uncertainty over leadership. At the start of the siege, John of Brienne as king of Jerusalem was chosen as de facto commander, but with no explicit agreement over future control of any conquests. John lacked authority over the crusaders from the west. The arrival of German and southern Italian contingents from 1217–18 onwards, and the papal legate Cardinal Pelagius in the autumn of 1218, held out the prospect of the arrival and assumption of command by Frederick II of Germany, who had taken the cross in 1215. Pelagius’s control of the substantial sums that reached the crusaders from the Lateran Council church tax, worth according to a 1220 papal account 35,000 silver marks and 25,000 gold pieces,41 allowed him to create a central treasury for indigent crusaders and to hire those in search of regular payment, giving him a significant voice in any decisions. Competing interests made consensus in an inevitably collective leadership hard to achieve, especially as, in common with earlier expeditions, choices were regularly debated with the wider community of the army.

83. The Nile at Damietta.

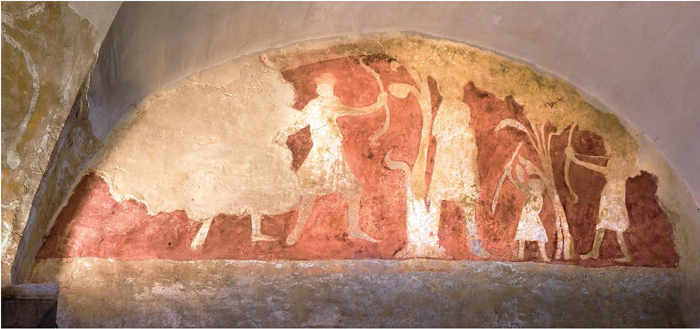

During the siege of Damietta, from May 1218 to November 1219, neither the crusaders, established on the west bank of the Nile opposite the city, nor the Egyptian field army, camped on the east bank to the south, risked a major confrontation. Operations revolved around blockading the city and starving it into submission. The waterlogged terrain, an Egyptian blockade of the Nile, and the lack of timber for barges and siege engines prevented direct assaults on the walls. Disease and supply problems periodically threatened the crusade with dissolution. Even after the main defensive system of a mid-stream tower and chains was captured in August 1218 and a new canal dug to outflank Ayyubid defences, it was only the abandonment of the forward Ayyubid camp early in 1219 that finally allowed Damietta to be surrounded. The new sultan, al-Kamil, had withdrawn to combat a possible coup and rebuild his control over his professional regiments. Thereafter, he conducted forays against the crusaders from a distance while trying to rally support from fellow Ayyubids in Syria and encourage them to launch attacks on Acre, a tactic that drew John of Brienne back to the Holy Land for a year, in 1220–1. Starvation and the absence of any prospective relief forced Damietta to surrender in November 1219. The nearby Delta port of Tinnis fell soon after, leaving the crusaders in control of the main eastern outlets of the Nile Delta. The next twenty-one months saw stalemate. Damietta was formally Christianised, its mosques converted into churches. One of those, dedicated to the English St Edmund the Martyr, the king of East Anglia, was immediately decorated with frescoes depicting the saint’s martyrdom at the hands of the Danes in 869, a painting commissioned by an English knight, Richard of Argentan.42 Such visual demonstration of new ownership formed a typical aspect of the aftermath of conquest by all sides during the eastern crusades where artistic and aesthetic assertions of power played essential public symbolic roles, as in Jerusalem in 1099 or 1187.

84. Thirteenth-century wall painting of the martyrdom of St Edmund, Cliffe-at-Hoo, Kent, perhaps similar to the one painted by crusaders at Damietta.

The turnover of crusaders continued alongside debates over the next course for the expedition; a negotiated settlement was mooted by the Egyptians. Diplomatic contacts were cast into unexpected relief by the appearance of the charismatic mendicant, Francis of Assisi, who attempted to convert al-Kamil in person during the summer of 1219, and by a shoal of prophecies that swept through the crusader army. Some foretold victory; others offered garbled echoes of the Asiatic conquests of Genghis Khan. The sense of divine providence may have influenced the rejection of al-Kamil’s offers to restore Jerusalem and Palestine west of the Jordan to the Latins in return for the crusaders’ evacuation of Egypt: the first in 1219, shortly before the fall of Damietta; the second before the crusaders’ advance towards Cairo in August 1221. Given the invaders’ military advantage in 1219, refusal of al-Kamil’s terms made sense, even though voices, probably including John of Brienne’s, were raised in favour of acceptance. Two years later, the balance of advantage was less obvious. However, any negotiated settlement would have meant the end of the crusade, leaving thousands of vows unfulfilled. On both occasions, but especially in 1221, the influence of the absent leaders Pope Honorius III and Frederick II, who had again taken the cross in 1220, inhibited abandonment of the crusade. Frederick’s arrival was regularly proclaimed as imminent, lending influence to the papal and German representatives, Pelagius and Duke Louis of Bavaria. By contrast, King John, who favoured acceptance, lacked a large army of his own and the death of his wife Queen Mary in 1212 had in any case effectively made him only regent for his daughter Isabel II.

More immediately, as in 1191–2, the defensibility of Jerusalem without the castles of Transjordan was questioned, while, with Palestine under the authority of al-Kamil’s brother al-Mu’azzam, sultan of Syria, the Egyptian ruler’s capacity to deliver on his promises was doubtful. By 1221 any negotiated peace would have challenged the carefully nurtured prophetic optimism among the crusaders and, under Muslim law and convention, would in any case be time limited. The 1219 and 1221 Egyptian offers spoke of tactical manoeuvres to cover al-Kamil’s immediate political weakness rather than a lasting Near East settlement. The 1221 offer came as both sides were consolidating their forces for an impending crusader march on Cairo which, despite his doubts, King John had returned from Acre to Damietta to join. With al-Kamil reinforced by Ayyubid allies from Syria, his offer may have been designed to sow dissent. In the event, the crusaders’ attempt on Cairo failed dismally, their army forced to surrender after being trapped by Nile floods and the Egyptian army. In return for the crusaders’ freedom and safe conduct, Damietta was evacuated (September 1221), ending the central action of the crusade and casting a possibly distorting retrospective glow on earlier failed diplomacy.

The negotiations of 1219 and 1221 fully exposed the Egyptian strategy’s contradictions. While the 1218 invasion stirred Ayyubid disunity, divisions that leaders of Outremer would exploit to their advantage over the following thirty years, the crusaders’ repeated refusal to trade Jerusalem for a withdrawal from Egypt questioned their objectives. Rejection did not necessarily come from blinkered zealous optimism. Their reading of the geopolitics of the Middle East persuaded enough of them that Jerusalem without its hinterland or a subservient Egypt was not viable in the medium let alone long term; and they were right. The Fifth Crusade’s intransigence implied that only conquest, a regime change or an inconceivable diplomatic volte face would allow for the safe return of Jerusalem, a city with a worrying tendency to succumb to hostile sieges (about six in 175 years to 1244). The Fifth Crusade seemed to be banking on a military knock-out or the implosion of the Ayyubid regime. Both were feasible. Latin armies from Palestine had campaigned throughout the Delta in the 1160s. Using methods of extreme brutality, Saladin had been able to subdue Egypt in a relatively few years. The Fifth Crusade and the later expedition of Louis IX both reached to within a hundred miles of Cairo. Yet no plan of how to manage Egypt in the aftermath of any victory existed. Perhaps some sort of Latin overlordship was envisaged, for which precedents were hardly encouraging. The diplomatic option held no better prospects. The demilitarised Jerusalem agreed in a deal struck between the Ayyubid Sultan al-Kamil and the western Emperor Frederick II in 1229 easily fell to Turkish freebooters in 1244.

The Crusade of 1228–9

The logic of the 1221 defeat was not lost on the rulers of the rump of Outremer or planners in the west. For the former, diplomacy was as important as conflict. Antioch and Tripoli, dynastically united since 1187, became increasingly absorbed in the politics of Christian Cilician Armenia and in cutting deals with local Syrian rulers. At Acre, territory was conserved and extended largely through a rhythm of diplomacy shaped by the expiry of the recurrent truces with Ayyubid neighbours in Damascus, Transjordan and Egypt, and by playing them off against each other. The politics of Outremer were complicated by the role of Frederick II, from 1225 absentee king of Jerusalem by virtue of his marriage to the heiress Isabel II (d. 1228). While preparing to honour his crusade vows of 1215 and 1220, he conducted direct negotiations with al-Kamil over returning Jerusalem. When Frederick finally arrived in Palestine in 1228, his role had been compromised by papal excommunication for dilatoriness, the death of his wife, and the hostility of sections of the Outremer political elite, including the Cypriot Franks, Templars and Hospitallers. After military manoeuvring by both parties, Frederick and al-Kamil reached a ten-year agreement (treaty of Jaffa, February 1229) that restored Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth and all of Sidon to the Franks, although the Haram al-Sharif (Temple Mount) was left in Muslim hands, with free access for Christian pilgrims. Despite attracting opprobrium from all sides, the 1229 treaty fitted a pattern established since 1192, signalling an asymmetrical concern over the status of Palestine: Transjordan and Syria were of far greater strategic and political significance to Egypt provided the religious sensibilities of the ulema were appeased by continued control of Jerusalem’s Islamic holy places. A German poet in Frederick’s army likened the deal to watching two misers trying to divide three gold pieces equally.43

The Politics of Thirteenth-Century Outremer

Frederick’s difficulties with the local baronage mirrored the fractured politics of thirteenth-century Outremer more generally. Although by the 1240s having gradually reasserted control over the territory between the Jordan and the Mediterranean, the Franks depended on the coastal ports, especially Tyre and Acre, for their wealth and power, supported by castles such as Athlit south of Acre, Margat between Tripoli and Latakia, Crac des Chevaliers in the Homs gap or, from 1240, Saphet in Galilee, all funded and held by the Military Orders. Even during the Frankish reoccupation of the Holy City (1229–44), Acre remained the capital of the kingdom of Jerusalem, the titles and jurisdictions of the twelfth century continuing often only as legalistic antiquarian memories, shadows or imitations. From 1219, Tripoli and Antioch were dynastically united under Bohemund IV and his successors, although each had been reduced to coastal ports and scattered castles, effectively isolated city states. There was little if any renewed Frankish rural resettlement after 1191–2. Outremer’s survival rested on income from commerce and its ability to defend itself, making it reliant on the trading Italian communes established in the ports – Venice, Genoa, Pisa – and the Military Orders – Templars, Hospitallers and Teutonic Knights, each with different, often competing, frequently hostile sets of interest. The potential for conflict was exacerbated by weak central political control. The royal dynasty failed to produce adult male resident rulers. From 1225, when Isabel II married Frederick II, until 1269, when Hugh III of Cyprus, a descendant of Isabel I, united the crowns of Cyprus and Jerusalem, the king was a distant absentee (Frederick and Isabel’s son, Conrad, 1225–54, and grandson Conradin, 1254–68), nominal rule resting in a series of usually and often violently contested regencies. Even after 1269, until his death in 1285, Charles of Anjou, the new king of Sicily, vigorously claimed sovereignty (sold to him by Mary of Antioch, another descendant of Isabel I) through agents sent east, leading to the bizarre position in the 1270s of the fast-diminishing Frankish kingdom squabbling over Sicilian or Cypriot legitimacy.

In the absence of a resident monarch, the local baronage, notably the Ibelin family, assumed authority. However, neither the barons nor the Italian communes nor the Military Orders were united; nor were the dominant cities of Tyre and Acre. This created an extraordinary spectacle of near permanent factional contest both between local interest groups and between them and representatives of absent monarchs, conflicts that inevitably sucked in the rulers and nobility of Cyprus. Outremer politics most resembled the infighting familiar in and between contemporary Italian city states. Between 1228 and 1243 the so-called War of the Lombards pitted King Conrad’s (in reality his father, Frederick II’s) representative, Richard Filangieri, supported by Tyre, the Hospitallers, the Teutonic Knights and the Pisans, against the Ibelins backed by Acre, the Templars and the Genoese. In 1231, to resist Filangieri, his opponents in Acre formed a commune. In 1242 the Ibelin faction prevailed when Tyre was captured. Nominal rule then passed between a parade of Cypriot and Ibelin regents. From 1250 to 1254, Louis IX of France exercised a form of parallel authority, while in the 1260s his agent, Geoffrey of Sergines, commander of the French garrison at Acre, actually served as regent. Unity was not achieved. In 1256–8 the Venetians and the Genoese took up arms in the War of St Sabas, a dispute only finally resolved in 1288. Venice had the support of Pisa, the Templars, the Teutonic Knights and part of the Ibelin clan; the Genoese the backing of the Hospitallers and other Ibelins. In the 1270s further disruption was caused by Charles of Anjou’s agent Roger of San Severino, who managed to secure the support of Acre, Sidon and the Templars, while Tyre and Beirut remained loyal to Hugh III (I of Jerusalem). All the while, from 1265, the Mamluks of Egypt were systematically dismantling what remained of the kingdom and Frankish Outremer.

This persistent internecine feuding was sustained by thirteenth-century Outremer’s wealth. It funded political conflict as well as providing the prizes all factions wished to acquire. Henry III of England’s brother, Earl Richard of Cornwall, reported after his crusade of 1240–1 that Acre alone was worth £50,000 sterling a year, significantly more than King Henry’s entire annual royal income.44 Until the advent of the Mongols in the Near East from the later 1250s gradually readjusted western Asian trade routes, Acre and the other Outremer ports provided major entrepôts for Mediterranean trade from across Eurasia: foodstuffs, spices, base metal, metalwork, porcelain, glass, sugar, perfumes, wine, jewels, slaves, pilgrims, relics, silk, linen, cotton, wood and specialities such as Tuscan saffron.45 ‘Antioch cloth’, whether or not actually manufactured in Syria, was a label that commanded high prices and conveyed social kudos across western Europe.46 A large suburb was added to Acre to accommodate its swelling population. The Templars were so wealthy that they were able to spend over a million bezants over two and half years after 1240, rebuilding their castle at Saphet. For families such as the Ibelins, in the east since the early twelfth century, Outremer was home and, just as elsewhere in Christendom, profits were there to be had. Visiting crusaders encountered a rich, polyglot and increasingly bilingual society (Arabic and Romance languages), where, as in Italy, the nobility lived in cities and where markets offered customers anything from exotic fruit to illuminated manuscripts. Viewed through an economic lens, Outremer was booming, its cities worth mercantile investment to the end. However, just as its wealth depended on international trade so its survival was predicated on international assistance.

ACRE MANUSCRIPTS AND ‘CRUSADER ART’

The aesthetics of the crusades lacked distinctive form. In painting, sculpture, architecture, manuscript illumination, songs, poems, plays, clothes, food, weaponry, heraldry, the art of crusaders drew technique, inspiration and styles eclectically from prevailing cultural ambience. For the Franks of Outremer this included local influences – Greek, Syrian Christian, Arab, Armenian – as well as European (see ‘The Melisende Psalter’, p. 138, and ‘A Palace in Beirut’, p. 230). Although almost all the artefacts created by or for the Outremer Franks have not survived, it is hard to identify special Outremer style, except perhaps in concentric castle fortifications and in deliberate religious imagery on coins (St Peter in Antioch or the Holy Places in Jerusalem). Frankish ecclesiastical architecture, while incorporating local features such as domes and flat roofs, also relied on borrowing from western Romanesque, then Gothic models, making a religious point.47 Divorced from their devotional settings, Frankish architecture could be admired for itself: Mamluk conquerors seemed happy to incorporate looted Frankish Gothic doorways, columns and decorative sculpture as trophies into mosques and a madrasa in Cairo.48 Secular and domestic architecture and decoration appropriated indigenous styles, although in places, such as planned villages and suburbs, they introduced western ground-plans, such as two-storied houses opening directly onto the street, with individual plots of land behind.49

Similarly for western crusaders, content not form distinguished works associated with the war of the cross. Images of warrior saints such as St George, and of militant episodes from the Old Testament, proliferated in sculpture and illumination, as did what has been described as a ‘Christo-mimetic movement’ in art and relic collecting.50 Crusade-related themes became popular in devotional manuscripts, especially those associated with the court of Louis IX.51 Decorative schemes directly or indirectly focused on the crusade, such as the stained glass at St Denis showing scenes of the First Crusade or Louis IX’s Sainte Chapelle in Paris, a giant reliquary for the relics of the Passion. Inevitably, visual art needed to be framed in conventional styles to engage the conscious or subliminal understanding of the viewer. The luxurious textiles, clothes, jewellery or metalwork that wealthy crusaders took with them or acquired on campaign lacked specific crusader motifs, except perhaps in the manuscripts they purchased or commissioned.

85. A volume commissioned in Outremer in 1250–4 on Louis IX’s crusade.

In Outremer, the Franks embraced regional diversity while importing western styles and artisans, such as painters and illuminators from Italy, Germany, England and France. Louis IX’s stay in the Holy Land between 1250 and 1254 appears to have stimulated local luxury manuscript production at Acre, probably supported by French artists in his entourage. One volume, the so-called Arsenal Bible, comprising lengthy vernacular extracts with 115 illuminated scenes showing Byzantine as well as French influence, has been attributed to Louis’ stay and even to his personal patronage and use. Although only a handful of manuscripts have been tentatively identified as originating in Acre, it appears that production increased in the final years before the city’s fall, a sign of Acre’s international status and the continued presence of wealthy patrons, some possibly visiting crusaders, most probably laymen or members of the Military Orders, as the texts are in the vernacular: works of history, literature, law and military advice. The styles reflect continuing borrowing between Christian Levantine, western European and Greek models. This typified a cultural identity that, both in Outremer and western Europe, even when highlighting specific ideological messages, exploited but did not transform existing fashions, techniques and expectations.52

The Crusades of 1239–41

By incremental diplomacy backed by threats of force, the thirteenth-century kingdom of Jerusalem had gradually recovered lands in Galilee and west of the Jordan, a process the crusades of 1239–41 reinforced. In the autumn of 1234, in good time to prepare for the end of the ten-year 1229 truce, Pope Gregory IX (1227–41), a veteran of preaching the Fifth Crusade, called for a new eastern campaign. In addition to the usual spiritual and temporal privileges to active crucesignati, he offered indulgences for vow redemptions to any who contributed materially, instituted a clerical income tax, and proposed a new ten-year garrison force for Outremer. Preaching was assigned to the new mendicant orders of Dominican and Franciscan friars.53 The funding system allocated proceeds from legacies, alms and vow redemptions to crusaders, chiefly the already well provided. With none of the crowned heads of western Europe committing themselves, recruitment revolved around great nobles, prominently Duke Hugh IV of Burgundy; Counts Theobald IV of Champagne (posthumous son of the lost leader of the Fourth Crusade) and Peter of Brittany; and Earls Richard of Cornwall and Simon of Montfort of Leicester (Henry III’s brother-in-law). The muster of French nobles was the largest since the Fourth Crusade. On both sides of the Channel, aristocratic recruitment operated as part of complex arrangements of reconciliation after periods of rebellion and dissent. The resulting campaigns in Palestine in 1239–41 lacked coherent timing, direction or leadership. Modest diplomatic successes were achieved chiefly because of Ayyubid division. The main French contingents arrived in 1239, their stay of a year marked by indiscipline, confused strategy between Damascus and Egypt, and being mauled in battle with the Egyptians near Gaza (13 November 1239). Simultaneously, al-Nasr, ruler of Kerak, had briefly reoccupied Jerusalem. Nonetheless, the presence of western troops was unwelcome to the Ayyubids, so deals were secured with Damascus and Kerak covering Frankish control over Galilee and southern Palestine, including Jerusalem. Richard of Cornwall’s even briefer stay (October 1240–May 1241) witnessed the rebuilding of a fort at Ascalon and a largely empty treaty with Egypt confirming the agreements of the previous year over lands outside the sultan’s control. Prisoners taken at the battle of Gaza were released from Egyptian captivity and Earl Richard was allowed to bury the remains of some of those killed in the battle, gestures that earned the earl more praise than for any other action seen on these ramshackle crusades. Nevertheless, by the end of 1241, the kingdom of Jerusalem appeared secure, with most of its pre-1187 lands west of the Jordan restored except for Nablus; the port of Acre booming; the main Holy Places, barring Hebron, under Frankish jurisdiction; and calm diplomatic relations with the Ayyubid princes. Yet the insignificance of these arrangements in the wider scheme of Asiatic geopolitics was soon revealed.

CRUSADERS’ BAGGAGE

Whatever plunder and booty crusaders acquired on campaign, few initially set out empty handed. The symbols of pilgrimage, the scrip and staff, took their place alongside the necessities of travel: clothing, arms, armour, cash (in currency, plate or ingots), cooking utensils, containers for food and drink, pack animals, harnesses and wagons. The clergy carried travel altars, liturgical books, religious vessels and writing implements. According to one witness, in 1096 the less well off piled their children and modest possessions onto simple two-wheeled carts to which they tied their cattle.54 The presence of extensive, slow-moving baggage trains provided a much commented on feature of land expeditions. The wealthy habitually travelled with the accoutrements of their class. Beyond direct military or obvious financial requirements, such as weaponry, silver ingots or, as in the case of the English noble William Longsword in 1249, saddle bags stuffed with cash, luxury items, such as gold or silver plate, jewels and precious textiles, could also be bartered for supplies or exchanged for local currency.55 Some objects served social as well as military purposes. When he reached Constantinople in 1097, Tancred of Lecce wanted a tent large enough to act as a hall for his growing cohort of clients, while the Bolognese crusader Barzella Merxadrus used his tent at Damietta in 1219 to live in with his wife.56 Barzella’s tent was equipped with furniture. Commanders took signs of their cultural identities with them. Richard I travelled with what he claimed was King Arthur’s sword Excalibur, while his great-nephew, the future Edward I, carried a manuscript of Arthurian stories with him to Acre in 1271. The sometimes lavish nature of the goods that accompanied crusaders is displayed in surviving wills and inventories. In his will drawn up at Acre on 24 October 1267, the English crusader Hugh Neville’s bequests included, in addition to cash, horses and armour, a standing goblet decorated with the arms of the king of England, a gold buckle, other buckles studded with emeralds and a gold ring. A year earlier, an inventory of the goods at Acre of the recently deceased French crusader Count Eudes of Nevers provides elaborate insight into aristocratic travelling style, itemising rings, enamels, bejewelled belts and hats, gold and silver cups, goblets, jugs, ewers, bowls, basins and spoons, some garnished with gems and enamel; expensive cotton and linen fabrics including numerous bed hangings, tablecloths, napkins, quilts, even the count’s cloth of gold shroud, as well as quantities of curtains and carpets; gloves, leggings and shoes, alongside a miscellany of whistles, armour, spurs, weapons, banners, trunks and chests, food, drink, culinary utensils, leather bottles; the contents of the count’s wardrobe; the furnishings of his travelling chapel – chalice, vestments and breviary; and three books: two romances and a ‘romanz de la terre d’outre mer’, either a translation of William of Tyre or possibly a version of one of the texts in the popular chanson de geste Crusade Cycle. While some of this bounty may have been purchased in Outremer, where certainly the whole lot was put up for sale to pay the count’s debts, the bulk would have come with him from France. Crusaders took their intimate possessions with them just as they did their servants, clerics and military entourages.57

86. Loading up, from the statutes of the fourteenth-century crusading Order of the Knot.

The French Crusade, 1248–54

In August 1244, Khwarazmian Turkish mercenaries in the pay of Sultan al-Salih of Egypt, invading Syria and Palestine from Iraq on the sultan’s behalf, captured Jerusalem, slaughtering Franks and desecrating Christian shrines, before joining an Egyptian Ayyubid army that routed a combined Syrian Ayyubid-Frankish army at Forbie near Gaza in October. Soon, most of the Frankish gains of 1241 in southern Palestine were wiped out; Ascalon was lost in 1247. The future of Frankish Outremer looked precarious, contingent on regional forces over which the Franks exerted no real influence. Al-Salih’s consolidation of power over Syria as well as Egypt, supported by his increasingly powerful personal Mamluk askar (the Bahriyya or Salihiyya), seemed to recreate the encirclement of Saladin’s day. The western European response, although more modest than that after 1187, produced the best organised eastern crusade. Its complete failure imposed a bleak, forbidding realism.