CRUSADES IN SPAIN

The failure of western Christendom’s armies in the eastern Mediterranean stood in contrast to Christian rulers’ success in Spain. In 1248, the same year that Louis IX embarked for the Levant, Fernando III of Castile accepted the surrender of Seville, the last great metropolis of al-Andalus (‘the land of the west’), leaving only Granada in Muslim hands on the Iberian Peninsula. For the previous two centuries Spain had presented both a parallel and a contrast to the crusades in the east. Observers as different as Urban II in the 1080s and 1090 and the Damascus scholar al-Sulami in 1105 regarded the wars in Spain as part of wider Christian assaults on Islamic lands. For al-Sulami, the Franks, encouraged by Muslim disunity, had conquered Sicily and made extensive conquests in Spain before descending on the Near East,1 while during the First Crusade Urban encouraged Catalan counts to concentrate on the local struggle rather than the Jerusalem adventure: ‘it is no virtue to rescue Christians from the Saracens in one place, only to expose them to the tyranny and oppression of the Saracens in another’.2 However, except in rhetoric and possibly spiritual incentive, the circumstances of eleventh-century Christian advances in Spain were distinct from those surrounding the Jerusalem wars. Crusading did not inspire the conquest of al-Andalus, Muslim Spain. Instead, the formulae of cross, papal privileges and remissions of sins were applied to pre-existing secular rivalries, finding natural affinity within long-standing self-justifications of political contest.

The Spanish ‘Reconquest’

War between Christian lords in the far north of the Iberian Peninsula and Muslim rulers to their south was not new in the late eleventh century. Exchange and competition across Christendom’s Spanish frontier pre-dated crusade indulgences, establishing patterns of conduct and traditions later coloured but not shaped by the negotium crucis. The political history of early medieval Spain hardly compared with that of Europe north of the Pyrenees. In the early eighth century, the former Roman province of Hispania, dominated by an entrenched Christian Visigothic kingdom based at Toledo, was overrun after 711 by north African Berber armies commanded by Arab generals. A Muslim emirate with a capital at Cordoba (756–1031), rebranded in 929 as an autonomous caliphate, emerged under descendants of the Near Eastern Umayyad caliphs of the seventh and eight centuries. Only in the north beyond the Duero valley, in the Cantabrian mountains and the Basque country, did Christian lordships survive. Elsewhere, the Arab conquest led to a slow process of Arabisation and even slower Islamicisation: by 900 only about 25 per cent while in 1000 perhaps about 75 per cent of the population of Spain may have been Muslims. Jews and Christians, as People of the Book, paid the jiyza or poll tax, and adopted the customs and language of their masters. Arabic-speaking Christians, known as Mozarabs, developed their own liturgies. Early medieval Spain, as elsewhere around the Mediterranean, witnessed a pragmatic convivencia (literally ‘living together’) characterised by separation and indifference not tolerance or harmony, cultural synthesis combined with economic competition and potential social hostility.

The earliest Christian enclave to cohere into a perceptible lordship developed around Orviedo in the Asturias which, by the early tenth century, had expanded south to incorporate a new capital, León, and the county of Castile in the upper Ebro valley. In the western Pyrenees, lordships later known as Navarre and Aragon emerged. In the early ninth century a Carolingian county was established in Catalonia after Charlemagne’s attempts in 778 to create a Frankish march further south around Zaragoza had failed in a campaign later made famous by the Song of Roland’s embroidered stories of the defeat of its rearguard at Roncevalles. Apart from Catalonia’s involvement in trans-Pyrenean Francia, the politics of the Christian principalities revolved around local rivalries and raiding across the frontier with the Cordoba caliphate. The Song of Roland’s depiction of the massacre of a Frankish regiment by Pyrenean Basques in 778 as an epic contest between heroic Christian knights and demonic armies of Islam reflected eleventh-century French fiction, not eighth-century Iberian realities. After the eighth century, the Spanish frontier wars only began to be incorporated into grander perceptions of cosmic religious confrontation once they attracted French recruits and serious papal interest in the eleventh century.

How far, if at all, these local struggles for material existence and advantage had previously been perceived by Christian Spaniards in religious terms remains unclear, as does the genesis of the idea that the conquest of Muslim Spain constituted a reconquest, the Reconquista of nationalist myth. Early versions of the Reconquest idea were crafted in the late ninth century in the Asturias to demonstrate a legitimising link between Asturian kingship, the old Visigoth rulers, and a providential mission to restore Christian rule to the peninsula. This justified raids and campaigns against the Moors (people from the north African coast, Mauretania, Berbers) in religious terms, an elevation of purpose and consolidation of political identity familiar across early medieval western Europe, and not restricted to Christian rulers. The great Cordoban vizier, al-Mansur (i.e. ‘the Victorious’, 976–1002), declared his attacks on Christian territory to be jihads and flaunted his Koranic credentials. However, religious frontiers competed with many others in early eleventh-century Iberia. While the power of the Cordoban caliphate made it a prime threat to its Christian neighbours, political competition saw Christians fighting Christians, Muslims fighting Muslims, and all engaging in alliances and economic and commercial exchange across religious divides.

Politics and cash, not religion, provided the impetus for the wars after the sudden collapse of the Cordoban caliphate in 1031, which was replaced by unstable but still wealthy so-called taifa or ‘party’ kingdoms.3 These competing Muslim principalities actively sought external military aid regardless of religion. Christian rulers soon took advantage, entering into agreements under which they were hired by taifa rulers in return for parias, annual tributes, effectively protection money, paid in gold. The urban economy of al-Andalus had exploited the gold coming across the Sahara from west Africa. The parias gave Christian rulers of the north direct access to large quantities of gold, a very scarce commodity in the rest of western Europe, consolidating their power, creating new opportunities to expand their frontiers at their paymasters’ expense and to attract attention from beyond the Pyrenees. This last included fashionable ideas of holy war. However, religion was not a factor in paria agreements. In one, with the emir of Zaragoza in 1069, for 1,000 gold pieces a month, Sancho IV of Navarre promised not to allow ‘people from France or elsewhere’ to cross his kingdom to attack Zaragoza or to ally with anyone, Christian or Muslim, against the emir.4 Such arrangements encouraged a mercenary free trade. Anyone – Muslim or Christian – with sufficient military credentials and armed support could sell their services to the highest bidder. The most famous freelance was the Castilian nobleman Rodrigo Diaz, El Cid (c. 1045–99). As well as serving Fernando I of León-Castile (1035–65) and his son Alfonso VI (1065–1109), Rodrigo fought for the emir of Zaragoza (1081–6) against Catalans and Aragonese. From 1089, he operated his own army, fighting Christian as well as Muslim rulers in eastern Spain before creating for himself an independent taifa lordship at Valencia (1094–99) that survived until 1102.5 Christian rulers still competed with each other, no more united than their Muslim neighbours.

Such opportunism sought the respectable cloak of ideology, conquest justified as reclaiming territories that ‘originally belonged to the Christians’ or as ‘the recovery and extension of the Church of Christ’, a claim made explicit by Alfonso VI after capturing Toledo in 1085 when he wrote of the city, after 376 years of Muslim rule, now restored ‘under the leadership of Christ . . . to the devotees of His faith’. Urban II echoed the theme, writing that Toledo had been ‘restored to the law of the Christians’.6 The religious rhetoric of Reconquest hardly concealed the secular drivers of the campaigns against the taifa kingdoms once Christian rulers sought political control rather than financial exploitation. By the 1090s, the frontier of al-Andalus had been pushed south to a line roughly from Coimbra in the west to north of Tarragona in the east, with a Christian salient extending down to Toledo on the Tagus in the centre. The Christian gains were modest and hardly presaged any inevitable annexation of the whole peninsula; al-Andalus still dominated most of the richest regions. These late eleventh-century wars were of piecemeal conquest and, in places, expulsion. One abiding feature of the Reconquest remained the custom that cities were surrendered through negotiation, with garrisons and civilians allowed to depart, a pattern repeated right up to and including the final expulsion of the Moors from Granada in 1492. Unlike some Levant campaigns, and even where complicated by north African interventions, the Spanish wars were fought as between neighbours, not aliens.

Holy War

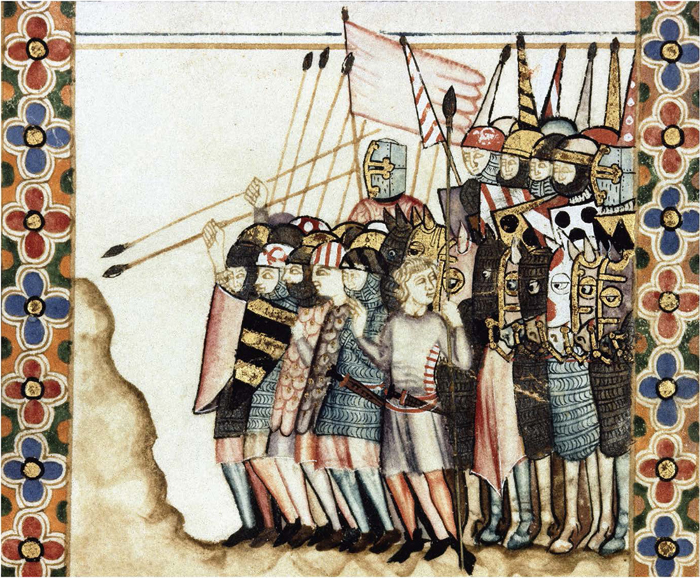

The indigenous political and religious justification of Reconquest provided fertile ground for holy war as developed by the eleventh-century papacy, just as the wars themselves attracted trans-Pyrenean recruits. A Catalan-Aragonese attack on Barbastro, north-east of Zaragoza, in 1064–5, drew recruits from Burgundy, Normandy, Aquitaine and possibly Norman Sicily perhaps lured by an offer of remission of penance and sins by Pope Alexander II, who around the same time provided a blanket just-war authorisation when fighting Muslims who oppressed Christians. In one respect, the warriors at Barbastro followed a new uncompromising militancy, their brief occupation of the town marked by violent atrocities later familiar from the First Crusade. Foreigners brought with them an ignorance of Muslims and a confident brutish martial spirituality that chimed with the policies of contemporary popes. Spain became a laboratory for hegemonic papal policies in replacing the Spanish Mozarab liturgy with a Roman one and in the spiritualisation of war, particularly against Islam. In 1073, Gregory VII argued that Spain ‘from ancient times belonged to the personal right of St. Peter’ and, despite long Moorish occupation, still did, a claim combated by Alfonso VI in 1077 when he styled himself ‘emperor of all Spain’.7 Further trans-Pyrenean links were witnessed by the penetration of Cluniac monasticism into northern Spain, from mid-century under the lavish patronage of the kings of León. In 1064, Raymond Berenguer I of Catalonia promulgated a Peace and Truce of God, a mechanism popular in places north of the Pyrenees whereby local lords swore to keep the peace and protect ecclesiastical property. By the 1080s, marriages of Spanish princes and princesses to spouses from north of the Pyrenees had become familiar. All five of Alfonso VI’s legitimate wives came from outside Spain, a sign his dynasty had entered the family of western European rulers, even if domestically Alfonso may have retained local tastes: one of his mistresses may have been the daughter-in-law of the emir of Seville.8

The fusion of border conflicts, Reconquest and holy war in Spain came from the coincidence of the invasion of al-Andalus by the Moroccan Almoravids in 1086 and the promotion of penitential war by the papacy in the generation before the First Crusade. Originally a radical group of Islamic fundamentalists from the margins of the Sahara, by the early 1080s the Almoravids – the al-Murabitum or ‘people of the ribat’ (Islamic frontier military monasteries) – had conquered Morocco, rigorously enforcing austere religious observance somewhat at odds with the relaxed sophistication of al-Andalus. By the mid-1080s they were ready to extend their authority across the Straits of Gibraltar into al-Andalus. With pressure growing from the north in the aftermath of Alfonso VI’s capture of Toledo in 1085, the taifa emirs, led by Seville, had little option but to invite Almoravid aid. The invasion, under Yusuf ibn Tushufin, led to the defeat of Alfonso at Sagrajas in 1086. While providing apparent support for al-Andalus, over the next quarter of a century, by force, coercion and diplomacy, the Almoravids absorbed the taifa emirates into their own empire, the last, Zaragoza, falling in 1110. The Almoravids’ destruction of the paria system and their military threat encouraged the reactive adoption of Christian holy war. The arrival of the north Africans added a new and, for both Christian opponents and indigenous Muslims, an unwelcome and complicating dimension to Iberian politics. This was recognised by the distinction drawn by twelfth-century Christian Spanish writers between the Muslims of al-Andalus, ‘Moors’ and ‘Hagarenes’, with whom business could be done, and alien invaders, ‘Moabites’(Almoravids) and, later, ‘Assyrians’ or ‘Muzmotos’ (the Almohads, invaders from north Africa from the 1140s), with whom it could not.9

Into this new political situation arrived foreign soldiers with the ideology and institutions of penitential warfare. In 1089 and 1091, Urban II offered the same remission of sins given to Jerusalem pilgrims to those who helped rebuild the city and church of Tarragona, across the frontier fifty miles south of Barcelona, as the city was intended as a ‘wall and bastion against the Saracens for the Christian people’.10 The First Crusade did not deflect Urban from support of the Tarragona enterprise, urging local counts to fulfil their crusade vows not in the east but nearer home. In the event, Jerusalem seems to have proved a greater draw, in Christian Spain as elsewhere. However, Urban’s elision of objectives stuck. Peter I of Aragon (1094–1104) took the cross for Jerusalem in 1100. A year later, besieging Zaragoza, he was described as wearing his cross and displaying banners of the cross. The siege castle he built was nicknamed ‘Juslibol’, ‘God Wills it’, the slogan of Clermont.11

The subsequent incorporation of crusading institutions – bulls, indulgences, temporal privileges and cross – only gradually refined older associations of conquest and religious war. The past was reinvented to accommodate holy war. From around 1115 the patronal saint, James the Apostle, became a ‘knight of Christ’, perhaps in part as a potent competitor to contest papal proprietary claims for St Peter.12 Other saintly recruits included popular heavenly crusading patrons the Virgin Mary and St George, but also, in León, the less obvious seventh-century scholar Isidore of Seville. However, local traditions of non-violent association of Christians and al-Andalus Muslims continued to shade crusade stereotypes, as in the literary treatment of Rodrigo Diaz, El Cid. Both the twelfth-century Historia Roderici and the early thirteenth-century epic Poema de Mio Cid admit to Rodrigo’s friendship with Muslims and the shortcomings of Christians as well as Moors. The tone of crusading is absent.13 The insinuation of crusading into Spain through papal bulls and the example of the Jerusalem wars was not comprehensive. Crusading was not associated with every campaign nor did it determine politics or military strategy. The most concrete association of holiness with war found expression in the imported Military Orders, their indigenous imitators and crusade taxation. The Iberian reality of shared space with other religions tempered the demonising posturing and religious conflict familiar in the rest of Latin Christendom. Only in the later Middle Ages did memorialised crusade models more obviously encourage aggressive cultural discrimination and the active social pursuit of an exclusive divine mission.14

91. St James the moor killer by Tiepolo.

92. Convivencia? A Christian and a black Moor playing chess.

The Spanish Crusades

The legacy of the First Crusade and its apparatus lent patchy definition to holy war in Spain. Special interest was shown by popes with experience as Spanish legates: Cardinals Rainier (Paschal II, 1099–1118), Guy of Burgundy (Calixtus II, 1119–24) and Hyacinth (Celestine III, 1191–8). However, the initiative for seeking crusade formulae came chiefly not from Rome but from Iberian commanders wishing to enhance existing military schemes. Paschal II offered remission of sins to encourage Spaniards to resist the lure of the Jerusalem war in favour of fighting the Moors and Almoravids at home.15 At the request of the Pisans, the cross, a papal banner and remissions were granted to an ephemerally successful Pisan-Catalan-southern French campaign against the Balearic Islands in 1113–14, and possibly for a planned assault on Tortosa. Those who died helping Alfonso I ‘the Battler’ of Aragon capture Zaragoza in 1118 or contributed to restoring its church were rewarded with papal remissions. Spain’s moral and strategic equivalence with the Holy Land was confirmed by Canon XI of Calixtus II’s First Lateran Council of 1123. This equated those taking the cross for Jerusalem with those for Spain, a stance reiterated by regional church councils and Calixtus’s granting to crucesignati in Catalonia the ‘same remission of sins that we conceded to the defenders of the eastern church’.16 The rhetorical incorporation of Spain with the Holy Land found an echo in Archbishop Diego Gelmirez of Santiago’s 1125 fanciful project to attack Jerusalem via north Africa: ‘let us become soldiers of Christ . . . taking up arms . . . for the remission of sins’.17 By 1150, this redefinition of the Reconquest as cognate to the Jerusalem war was reflected in Leónese and Castilian chronicles, with their themes of revenge and militant scriptural references. Most strikingly, in 1131, Alfonso I of Aragon-Navarre (d. 1134) formally – if abortively – bequeathed his kingdom jointly to the Templars, Hospitallers and the canons of the Holy Sepulchre; in the 1120s he had toyed with the creation of a Templar-style militia Christi to combat Muslims and open a new way to Jerusalem.18

93. Archbishop Gelmirez blesses two knights.

The association of Reconquest with crusade remained contingent not automatic. In 1146 the Genoese attempt on the port of Almeria was described in secular terms whereas in 1147, with the Second Crusade to the east already launched, a renewed ultimately successful Genoese attack with Alfonso VII of Castile attracted both the rhetoric and institutions of holy war. ‘Redemption of souls’ had been offered even before Alfonso secured crusade status for the new attack from Eugenius III. While in practice the initiation and execution of the Almeria campaign owed nothing to the eastern expedition, it easily attracted the convenient aura of the Holy Land war, as did the Catalan-Genoese siege of Tortosa in 1148 that elicited a new papal grant of indulgences, ‘which Pope Urban established for all those going for the liberation of the eastern church’.19 The piggy-backing of the Reconquest onto the Jerusalem war was emphasised by Afonso of Portugal’s employment of passing crusaders in the successful siege of Lisbon (July–October 1147). This represented part of a pattern whereby fleets bound for the Holy Land attacked Muslim seaports, for pay, plunder, glory and winter anchorages: King Sigurd of Norway in 1108 (Sintra, Alcácer do Sal); the North Sea fleets of the Second Crusade in 1147 (Lisbon), and their successors in 1189 (the Algarve and Silves) and 1217 (Alcácer do Sal). While lacking separate crusade bulls, these interventions reinforced a perceived unity of purpose and merit between Spain and the Holy Land. Yet the gloss of piety did not disguise the incentive of land and profit. The contemporary Poem of Almeria, celebrating the 1147 conquest, combined crusade motifs (St Mary, forgiveness of sins, ‘the trumpet of salvation’) with praise of chivalric values (‘the glory of waging war is life itself’; the Castilian knights ‘enjoy themselves more in war than one friend does with another’) and the promise of ‘reward of this life’ as well as the next: ‘prizes of silver, and with victory . . . all the gold which the Moors possess’: a distillation of the distinctive flavour of the Reconquest crusades.20

In Spain, as elsewhere, the failure of the Second Crusade dampened the popularity of formal trappings of the crusade. Occasional deployments of papal grants, cross and indulgences persisted, as for a Catalan campaign in the Ebro valley in 1152–3. A council at Segovia in 1166 proposed Jerusalem indulgences for those fighting in defence of Castile while during Cardinal Hyacinth’s two legatine missions of 1154–5 and 1172–3 the future pope, a tenacious crusade enthusiast, took the cross and offered remission of sins. In 1175, Hyacinth persuaded Alexander III to issue a fresh crusade bull in the face of a new danger posed by the Almohads, al-Muwahhidun, or ‘Upholders of the Divine Unity’. Puritanically fundamentalist, and like the Almoravids from desert margins of south Morocco, the Almohads sought to impose their vision of the original purity of early Islam on the Maghreb and al-Andalus. Under their founder Muhammed ibn Tumart (d. 1130, declared a mahdi in 1121) and his successor Abd al-Mu’min (1130–63), the Almohads quickly overran the decaying power of the Almoravids in north Africa and, from 1146, began to subdue the emirs of al-Andalus. By 1173, Muslim Spain had been annexed under Yusuf I (1163–84), who now directly challenged the Christian rulers to the north. Over the next quarter of a century, many earlier Christian advances were reversed. In 1195, Alfonso VIII of Castile, supported by a crusade bull of 1193, was defeated at Alarcos and the Tagus valley raided. Yet, politics still trumped religion: disaffected Castilians fought for the Almohads at Alarcos; a Muslim regiment joined Alfonso IX of León’s invasion of Castile in 1196. In response, in 1197 the nonagenarian Celestine III, former legate Hyacinth, promulgated full eastern crusading privileges against Alfonso IX.

The proposed crusade against Alfonso IX followed the Third Crusade’s reignition of the Jerusalem war as the standard for church-approved violence. In 1188, Clement III extended Holy Land crusade privileges to Spain, including proportionate indulgences for non-combatant material contributors and a grant of church revenues. Thereafter, unlike crusades against Baltic pagans and apostates, heretics or other Christian religious or political dissidents in Europe, crusades in Spain were automatically assumed to be equivalent in merit to those to the Holy Land, even if not always as important.21 In 1213, Innocent III cancelled the offer of crusade privileges in Spain except for Spaniards themselves in favour of his new Holy Land enterprise.22 By the early thirteenth century, crusade privileges became customary accessories to the Reconquest especially after the strenuous international preaching campaign preceding the crusade of 1212 that led to the crushing victory of Alfonso VIII of Castile and Peter II of Aragon over the Almohads at Las Navas de Tolosa, the true beginning of the process of reconquest that ended in 1492. While this campaign included recruits from across the Pyrenees (most of whom left before the climactic battle), and later Christian conquests attracted foreign settlers, the thirteenth century saw the Spanish crusade become the preserve of Spaniards alone, its traditions and institutions developing in parallel but distinct from the rest of western Christendom.

94. The Almohad banner captured at Las Navas de Tolosa.

Military Orders

The Military Orders supplied one example of this Hispanisation of crusading. As providers of frontier garrisons, recipients of alms, estates, villages and castles, the Military Orders were integral to the Reconquest. While attracting patronage in the form of land grants by the 1130s, from the 1140s the Templars and Hospitallers exercised military roles. The Orders’ combination of disciplined commitment, hierarchical control, directed endowment and military efficiency proved a model for local rulers to establish their own national Orders. As in the Baltic, the proximity of a frontier with non-Christian territories gave the Spanish Military Orders a status, power and significance denied similar national Orders elsewhere in western Europe. By 1180 every Spanish kingdom except Navarre had their own Order alongside the Templars and Hospitallers (who remained prominent in Aragon and Catalonia): Calatrava in Castile (1158); Santiago (1170) and St Julian of Pereiro, later known as Alcantara (by 1176) in León; Evora, later Avis (by 1176) in Portugal. Local fraternities sprang up defending individual frontier castles, although lacking the resources or institutional permanence of the larger national Orders. Another Order, La Merced (c. 1230) in Barcelona, dealt with ransoming captives from the Moors.

95. A Templar tower on the Ebro near Tortosa.

Patrons included pious nobles or merchants, as well as kings and clerics. The larger Orders became sufficiently established to attract international investment: by 1200 the Order of Santiago held property from the British Isles to Carinthia in southern Austria. The Orders of Alcantara (1238) and Calatrava (1240) were granted papal indulgences to any who fought with them against the Moors, embedding the sort of ‘eternal crusade’ adopted later in the thirteenth century by the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic. That these privileges only came towards the completion of the conquest of al-Andalus signalled the Orders’ wider political, social and cultural influence as they became firmly associated with royal power. Monarchs increasingly controlled them, helping configure Spanish politics as institutionally crusading long after any immediate Moorish threat had been extinguished.

The Thirteenth Century and Beyond

The patriation of the Spanish crusade allied the ideal of Christian holy war with wars that would have been fought anyway by armies gathered through normal secular processes of military obligation, dependence, clientage and alliance, with terms of service the same as for non-crusading warfare. The Spanish crusades could hardly be branded as pilgrimages. As the twelfth-century Poem of Almeria noted, beside religious inspiration, pay and booty provided necessary incentives. Increasingly, the Church, as a leading material beneficiary, provided fiscal subsidies. Initially, crusade privileges of the sort offered in 1123 may have been intended as a device to attract international support, southern France appearing especially fertile in recruits. However, cross-Pyrenean involvement declined. The battle of Las Navas de Tolosa on 16 July 1212 became iconic. Won by a coalition of Alfonso VIII of Castile, Peter II of Aragon and Sancho VII of Navarre, with most of their French allies having withdrawn a fortnight earlier, the victory over the Almohads under al-Nasir (1199–1214) was presented as providential and national, Spanish revenge for 711.

The victory’s material as well as ideological legacy was profound. Politically, Castile reaped the main reward, with al-Andalus exposed by the rapid collapse of Almohad power. Castile lacked competitors with the long minority of James I of Aragon after the death of Peter II in 1213, and the succession to the throne of Navarre of the distant count of Champagne in 1234. Alfonso VIII’s financial expedients that had paid for the 1212 coalition, including a 50 per cent levy on the Castilian Church’s annual revenues, provided a lasting model. Wrapped in crusaders’ mantles, subsequent Iberian rulers used the Church to subsidise their wars, including, from the mid-thirteenth century, a third of ecclesiastical tithe income (tercias) and regular appropriation of Holy Land clerical taxation, used alongside secular levies and forced loans. As with other European frontier regions in the later Middle Ages, the crusade allowed for the permanent extension of the fiscal and political power of the state.

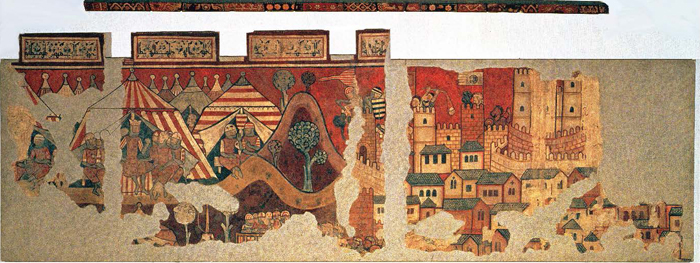

By 1250, only the emirate of Granada survived in Muslim hands, effectively a client of Castile. After 1212, the traffic of attack and conquest was for the first time largely one way, the rapid collapse of the Almohad Empire leaving a newly enfeebled al-Andalus behind. Whereas after Las Navas, Innocent III concentrated his crusade policy on the Holy Land, his successors Honorius III, Gregory IX and Innocent IV were enthusiastic supporters of applying the crusade to Spanish annexations in Iberia and the Balearic Islands and to plans to invade Morocco. From the 1220s, Fernando III of Castile (1217–52, and of León from 1230) identified his expansion southwards towards the Guadalquivir valley as a religious mission. He appears to have used a crusade bull of 1231 as open-ended consecration for his conquests of Cordoba (1236), Murcia (1243) and Seville (1248). In the 1220s, James I ‘the Conqueror’ of Aragon (1213–76) received crusade bulls for his successful invasion of the Balearic Islands (1229–35) and, from the 1220s onwards, his campaigns against Peniscola, Valencia (annexed 1232–45) and Murcia. Crusades were employed in the 1230s and 1240s by the Portuguese kings Sancho II (1223–47) and Afonso III (1248–79) as they pushed south into the Algrave. The international context was recognised in regular suggestions of extending the holy war to north Africa and Palestine. Within the peninsula, limited foreign involvement persisted: English and French troops joined the siege of Valencia (1238) and foreigners were settled in Seville after 1248. Although schemes for the invasion of Morocco and forays across the Straits of Gibraltar punctuated the next three centuries, only James I, by then crusading’s elder statesman, actively engaged with the eastern crusade, sending an Aragonese regiment to Acre in 1269 and attending the crusade discussions at the Second Council of Lyons (1274).

96. James the Conqueror besieging Palma, Mallorca, 1229–30.

As before, holy war was tempered by social and political reality. Annexations tended to be concluded by negotiation that secured some of the religious and legal rights of the conquered (for example, Mallorca in 1229, Valencia in 1238 and Murcia in 1243). Valencia retained its majority Muslim population. While some Muslims prudently apostatised, efforts at conversion were limited. Following conquest, in a reversal of roles, the mudejars (Muslims living under Christian rule) became protected second-class citizens with freedom to worship. Gradually, with increased Christian settlement, the Hispanisation and Christianisation of public spaces, religious sites, place names and secular landscapes, the accommodation with the mudejars frayed both locally and as part of public policy. Even by the end of the thirteenth century, there had been mudejar revolts. Thereafter, inter-faith communal relations tended to be practical not principled. From the mid-fifteenth century, especially in Castile, a political and cultural revival of militant neo-crusading produced active state intolerance and the imposition of Christian uniformity under Ferdinand II of Aragon (1479–1516) and Isabella of Castile (1474–1504), and their heirs Charles V (1516–56) and Philip II (1556–98). Despite rhetorical echoes, the persecution and final expulsion (1609–14) of mudejars and moriscos (descendants of Muslim converts to Christianity) belonged to a different world to that of the Spanish crusades of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The fall of Seville in 1248 concluded the rapid Christian territorial advances of the previous quarter of a century. However, wars continued with Granada; fresh threats came from the new Marinid rulers of Morocco, who invaded Spain in 1275, 1276 and 1282–3; occasional military excursions continued to north Africa (for example, the Castilian attack on Salé in 1260); and a prolonged struggle was waged for control of the Straits of Gibraltar, accompanied by a scattering of crusade privileges. Alfonso XI of Castile (1312–50) pursued a concerted Reconquest policy, regularly backed by crusade bulls. He defeated a major Marinid invasion at the River Salado in 1340 and, with international aid, captured Algeciras in 1344 as well as unsuccessfully besieging Gibraltar (which had been in Castilian hands since 1309) in 1333 and 1349–50, the second attempt ending when the king and many of his troops succumbed to the Black Death. The subsequent half-century of armed co-existence was broken around 1400 by a revival of Christian aggression. In 1410 the Castilians annexed Antequera. In 1415 the Portuguese capture of Ceuta on the north African coast was supported by crusade indulgences despite the complications of rival papacies during the Great Schism (1378–1417).

From popular literature to frontier plundering, the culture of crusading continued to suffuse Spanish aristocratic society, especially in Castile which from the thirteenth century possessed the only land border with Granada. Materially, in the fifteenth century, as elsewhere in Christendom, crusade bulls, preaching and indulgences were primarily fiscal devices, aimed at raising money through the sale of the crusade indulgences. From the pontificates of Martin V (1417–31) and Eugenius IV (1431–47), the Spanish bula de crozada became standardised, offering increasingly lowered fixed flat rates of purchase to attract more customers. In 1456 the Spanish Borgia pope Calixtus III (1455–8) extended the indulgence to the dead in purgatory. These bulls provided Iberian rulers with status and cash; and popes with international prestige and diplomatic influence. They became entrenched in Spanish public life, surviving the reforms of the penitential indulgence system at the Council of Trent (1545–63) and persisting in attenuated form until finally abolished by the Second Vatican Council (1962–5).

The ideology of crusade and Reconquest, sustained by the continued power of the Military Orders under royal command, lent an indelible providential tinge to the presentation of national identity. By the end of the fifteenth century, Castile itself was being promoted as a Holy Land in its own right, its Christian inhabitants the new Israelites, in clear appropriation of earlier crusade rhetoric.23 Such claims suited royal domestic policy. Campaigning against Moors provided a convenient mechanism for controlling and directing energetic and restless nobles in an incontrovertibly respectable cause. An active crusading holy war tradition was revived in the mid-fifteenth century, with campaigns against Granada in the 1430s, a raft of papal bulls around 1450 and the capture of Gibraltar in 1462. The renewal of war against Granada by Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, 1482–92, leading to the final expulsion of Moorish political rule from the peninsula in January 1492, regularly attracted full papal privileges. In a bull of 1482, Sixtus IV drew explicit parallels with the Holy Land crusades.24 Crusade privileges were also extended to Portuguese campaigns in the Maghreb that had been a feature of their foreign policy since 1415. Indulgences were awarded for campaigns aimed at Tangiers, for example in 1471, and from 1486 these copied the full Castilian Granada grants, repeated in 1505, 1507 and 1515. Charles V’s seizure of Tunis in 1535 was presented in crusading terms. As late as 1578, King Sebastian of Portugal (1557–78), supported by indulgences and papal legates, died fighting Moors in Morocco at the battle of Alcazar.

97. The surrender of Granada to the Catholic Monarchs by Muhammed XII in 1492, wood relief, c. 1495.

Wars in Morocco and Tunisia, driven by pursuit of fame, political advantage and commercial hegemony, could be fitted into traditional Reconquest justification of defence or recovery of Christian territory. However, Sixtus IV’s 1482 Granada crusade bull also insisted on the crusade as a mechanism for spreading the Christian faith. This had become important as crusading formulae were applied to Spanish and Portuguese expeditions down the west African coast and to the islands of the eastern Atlantic from the reign of Eugenius IV (1431–47) onwards. Canon law going back to the thirteenth century allowed for the forcible subjugation of indigenous pagans if they resisted missionary work, hardly an objective or neutral test.25 However, while the rhetoric and emotions of crusading were freely applicable to the conquests of the Canaries (1402–96) and later the Americas, formal crusade apparatus was less easily translated. Only by analogy could the Atlantic conquests be viewed as Reconquest or by stretching the reach of global crusade strategy, as in Christopher Columbus’s insistence that his expeditions were conceived in the context of the recovery of Jerusalem.26 In 1455, Nicholas V had granted the Portuguese the right to conquer and enslave African unbelievers. However, in the bull Inter cetera (1493) regarding conquests in the newly discovered Americas, Alexander VI (1492–1503), another Spanish Borgia pope, insisted that conversion was the sole justification for political dominion over indigenous peoples. In the event, the Spanish-Portuguese treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which carved up future global conquests, ignored papal authority, implicitly severing the new conquests from crusading. After the establishment of New Spain, America’s formal connection with the crusade, as a province of the Spanish Empire, was confined to bula de crozada fund-raising. The conquistadors do not seem to have sought crusade privileges. Despite sharing a historical, religious, emotional and psychological culture with crucesignati, the conquerors of America did not take the cross.

The revival of the crusade during the Granada war of the 1480s depended as much on a recasting of Catholic Spain’s manifest destiny as it did on Aragonese and Castilian crusading traditions. Domestically, this conditioned the creation of an exclusive sectarian Christian society and, externally, informed the projection of Spanish imperialism. Images of past and future crusading combined to forge a dynamic sense of duty, supremacy and mission. Diplomatic rhetoric in early sixteenth-century Europe was larded with pious references to a new holy war against the Turks. In this, propagandists claimed a unique historic role for Spain, feeding a form of messianism that entered deep into national identity. The Spanish crusades played their part in the profound, occasionally dramatic, political, social and religious transformation of the Iberian Peninsula in the later Middle Ages. Their cultural legacy and tenacious myths coloured Spanish attitudes for centuries to come.

98. The Fascist crusader: General Franco.