BALTIC CRUSADES

The crusades in the Baltic were defined by materials: fish, fur, amber, timber, slaves; ships’ carpentry and rigging; stone and brick for forts, castles and cathedrals; metal for weaponry. As in Spain, the use of crusading formulae overlaid existing contest for land and wealth. Like Spain too, the long-term political outcome was a triumph for Latin Christendom. However, unlike Spain, in two of the three areas where crusades were instituted in the Baltic – in Prussia (chiefly modern Poland) and Livonia (modern Latvia and Estonia) but not the Wendish lands east of the Elbe – new forms of government were established by a crusading Military Order, the Teutonic Knights, not secular rulers. The Baltic ideology of conquest was borrowed from other theatres of crusading: defence of Christians; retribution for apostasy; revenge for past wrongs; recovery of lost Christian territory supported by due authority and righteous religious intent. However, justifications for the northern crusades also fed off older German traditions and more recent Scandinavian experience of warfare against neighbouring pagans, all the time displaying the unmistakable reality of tangible profit.

The Baltic crusades were fought for territory, trade and the pursuit of secular and ecclesiastical glory and imperialism. Until the thirteenth century, the region’s wars rarely attracted full Holy Land papal crusade grants of cross, preaching, remissions, privileges. The more frequent papal issues of limited remissions, of varying generosity and without other features of full crusade grants, built on pre-crusading attitudes to meritorious war. Two further aspects added to Baltic distinctiveness. For a century from the 1140s, German crusaders competed vigorously and occasionally violently with Danish kings. Moreover, these crusade wars, unlike those in the Levant or Spain, were directly associated with forced conversion. Bernard of Clairvaux explained in 1147 when sanctioning the adoption of Holy Land crusading symbols and privileges by the Saxon summer campaign against the pagan Wends: ‘They shall either be converted or wiped out’. This was, as Innocent III in 1209 declared to Valdemar II of Denmark, ‘the war of the Lord . . . to drag the barbarians into the net of orthodoxy’, a suspect principle in canon law, although elsewhere justified by Christ’s parable in Luke 14:23: ‘compel them to come in’.1

Origins

The Baltic crusades helped transform northern Europe. From the lower Elbe to Livonia, Estonia, Finland and the Gulfs of Finland and Bothnia, the subjugation, exploitation and ultimate Christianisation of its indigenous peoples imposed permanent political, cultural and environmental change. The campaigns revived German attacks on the western Slavs that had stalled after the tenth-century Ottonian kings of Germany had abandoned earlier advances following the great Slav rising of 983. The German tradition of sanctified wars against non-Christians in eastern and central Europe, stretching back through the tenth-century kings to Charlemagne in the eighth, provided precedents and an ideology of defending and expanding Christendom by force, an enterprise now joined by expansionist rulers of Denmark. The incentives for a new advance across the Elbe towards Pomerania were obvious, as a Flemish clerk put it in 1108: ‘These gentiles are most wicked, but their land is the best, rich in meat, honey, corn and birds; and if it were well cultivated none could be compared to it for the wealth of its produce.’2

The region’s politically fragmented lordships, tribes and extended families were divided by ethnic and linguistic differences. The Wends, western Slavs between the Elbe and the Vistula, were related to the Poles and Czechs. With territorial princes, market towns, ports and a polytheism ordered around a strong priesthood, well-stocked temples and numinous cultic sites, the structural similarities of Wendish society to its German and Danish neighbours eased frontier accommodation and post-conquest assimilation. The lands further east, from the Vistula to the Dvina and the Gulf of Riga, were inhabited by separate tribal groups of Balts: Prussians, Lithuanians, Latvians and Curonians. Less centralised than the Wends, political power was exerted by local chieftans whose warrior aristocracies exploited the countryside from fortified earthworks, backed by control of fertility cults. North of the Balts, scattered Finno-Ugrian communities from the Gulf of Riga, Estonia and the Gulf of Finland comprised extended families, temporary local confederations and strong religious nature cults. Across the region, religious practices supplied social cohesion and political identity. Whereas the Wends, after previous generations of regular contact, proved susceptible to German assimilation once conquered, the Balts and others proved more robustly hostile.

99. Baltic paganism: tree idols in Livonia.

In Germany and Scandinavia, as elsewhere, the First Crusade left its mark on the rhetoric of war and the habits of the nobility. The emperor Henry IV appeared to contemplate a journey to Palestine in 1102; King Eric of Denmark (1102–3), King Sigurd of Norway (1107–10) and Conrad of Hohenstaufen, the future Conrad III (1124), all travelled there. In 1108 a scheme to attack the Wends explicitly drew a comparison with the defence of Jerusalem.3 German literature cast epic heroes such as Roland as milites Christi.4 This coincided with renewed German political and ecclesiastical expansion into pagan western Slavic lands such as Pomerania, with religion as the touchstone of political submission and allegiance on both sides. Obliterating pagan cultic centres symbolised the transfer of power, even if the new rulers were previously pagans who, like Henry of the Wendish Obotrites (d. 1127), had converted to retain their status in the new religious and political order. Resistance or conquest was expressed through religion. Wendish independence was reasserted following Henry’s death by the reversion to paganism of the Obotrite prince Niklot (c. 1130–60). The Rugians’ defeat by the Danes in 1134–6 was signalled by enforced baptisms, their subsequent resistance by apostasy, and their final subjugation in 1168 by Valdemar I of Denmark (1157–82) through the destruction of their pagan idols at Arkona. The religious complexion of political conflict was a Baltic commonplace long before Bernard of Clairvaux’s offer of conversion or extermination of pagan races in 1147. However, conflicts were never binary. While in retrospect the missionary priest Helmold of Bosau justified the German campaign in 1147 as revenge for Wendish appropriation of previously Christian land and assaults on Christians, he also described the alliance shortly before between Count Adolf of Holstein, one of the 1147 campaign’s leaders, and Niklot of the Obotrites, one of its targets.5

1147

The extension of Holy Land privileges to Saxon princes at the Diet of Frankfurt in March 1147 during the Second Crusade was an opportunist attempt to engage the disaffected and potentially rebellious Henry the Lion, duke of Saxony (1142–80), in a general political reconciliation that King Conrad III hoped to achieve before leaving for Palestine. Reluctant to join the eastern crusade, Duke Henry posed a threat in the king’s absence. Having rejected his claim to the duchy of Bavaria, Conrad used giving the cross to Henry and his followers for their summer campaign against the Wends as a means of binding them into royal policy, the crusade acting as both surety and reward for good behaviour. At Frankfurt, Bernard of Clairvaux provided the necessary ecclesiastical blessing, subsequently securing a papal bull authorising the initiative. The essentially political context was reinforced by the involvement in the Wendish campaign of one of the king’s regents, Abbot Wibald of Stavelot; its peculiar character was acknowledged by one Holy Land crucesignatus who later wrote that the Saxon crusaders’ crosses ‘differed from ours in this respect, that they were not simply sewed to their clothing, but were brandished aloft, surmounting a wheel’.6 While the religious panoply of the campaign was supported by the presence of at least eight bishops, its priority remained secular. Church approval attracted international support, with the Saxons joined by Danes, including rival kings Canute V and Sweyn III, and Poles in a two-pronged pincer attack on Dobin, a small recently fortified Wendish outpost, and Demmin. The attack on Dobin under Duke Henry faltered, the Danes withdrawing before the fort surrendered. The Saxons followed soon after, throughout appearing anxious to protect the future value of their conquests.7 The raid on Demmin failed to reach its objective, diverting to besiege the richer prize of Stettin, a Christian city. Once the city’s religion was recognised, the Germans retreated. The 1147 campaigns, despite their crusade flag of convenience, proved entirely nugatory.

Conquest and Crusade

The official employment of precise crusade formulae did not recur in the Baltic with any regularity until the 1190s. A crusade bull of 1171 looked forward to an extension of holy war from Wendish Pomerania to distant Estonia.8 Otherwise the crusaders’ vow, cross and Jerusalem remission were absent. Depictions of the Danish and German conquest of Wendish Rugians and Obotrites, while including the language of religious war, acknowledged the motives of revenge, imperialism and greed. Of Henry the Lion’s Slavic wars, Helmold commented: ‘no mention has been made of Christianity, but only of money’.9 For pagans, too, material considerations balanced religious loyalty, one convert lord expressly demanding as a price of baptism the same rights of property and taxation as those enjoyed by Saxons.10 On both sides of a shifting frontier, priorities concerned political aggrandisement, German, Danish or Wendish; for the Danes and Germans, the creation of new trading posts and privileged immigrant settlements; for the Church, the endowment of new bishoprics and religious houses, in particular Cistercian monasteries. Despite occasional well-publicised brutality, conversion of the Wends consolidated conquest by offering integration: through baptism Slavs, Letts, Balts and Livs could become Germans. The convert son of the pagan Niklot ultimately inherited his father’s lands as the Christian lord of Mecklenberg. He assisted the destruction of the pagan temples on Rugen by Valdemar I of Denmark (1168); supported Christian missionary work and the Cistercians; and went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem (1172). His descendants patronised the Hospitallers and joined crusades to Livonia.11 If sustained by material advantage, enforced conversion worked even in thirteenth-century Prussia and Livonia where resistance was stronger and integration harder.

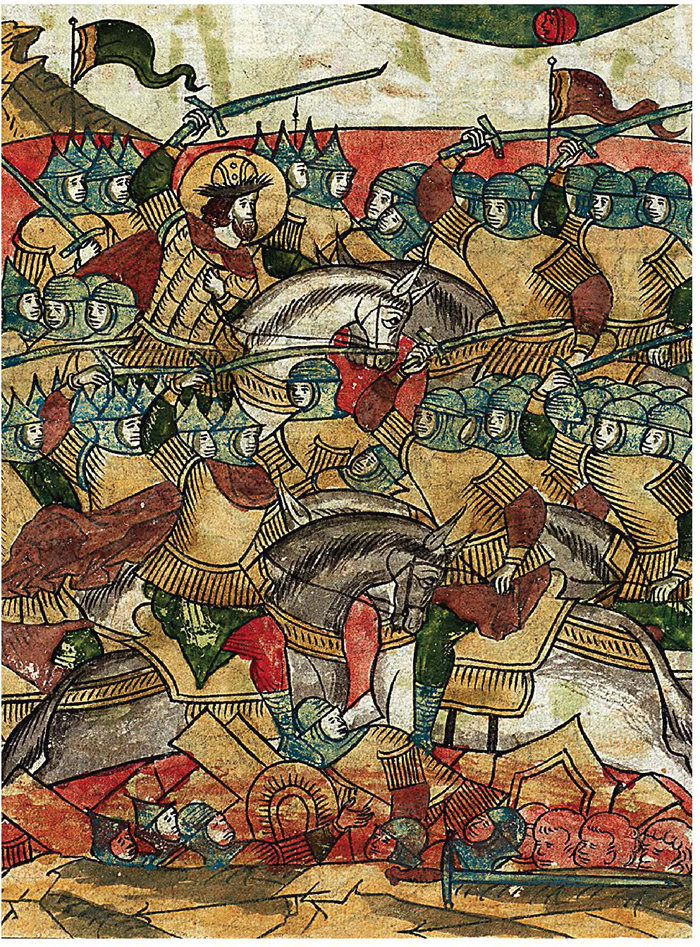

100. Danish soldiers under Valdemar I.

101. Conversion: a Christian pendant in thirteenth-century Livonia.

By 1400, the Baltic was ostensibly a Latin Christian lake, even if older habits persisted below the surface. Through laws, language, bishoprics, taxes, immigrants and iron-fisted rule, Latin Christendom reshaped the physical, mental and human environment. Conversion operated as integral to the transformation of political control. Yet only with the thirteenth-century conquest of the heathen tribes of Livonia, Estonia, Prussia, and Finland did crusading specifically play a significant role, even if inconsistently as papal priorities and regional demands did not always coincide.12 Papal enthusiasm to prosecute the Lord’s War was exploited by ambitious commercial and ecclesiastical elites in cities trading with the eastern Baltic, such as Bremen and Lübeck, and sustained by a steady stream of available recruits: one contemporary account of the unfortunate Livonian crusade of 1198 mentioned bishops, clergy, knights, the rich, the poor and merchants (negotiatores).13 Kings of Denmark and Sweden welcomed formal ecclesiastical sanction for their conquests. Ambitious clerics sought new ecclesiastical and monastic empires. Motives for conquest were grounded in material gain. Although technological limitations and political fragmentation made pagan communities of the eastern Baltic appear weak, their economic and commercial attractions were considerable as producers and traders in fur, fish, amber, wax and slaves. Recent archaeological study has suggested a thriving and growing economy that encouraged the heavy German investment to appropriate it.14

The crusade provided an ideology for exploitation and alliance with an imperialist church hierarchy. Conquests were justified as protecting missionary churches or punishing apostasy, their protagonists ‘knights of Christ’.15 In the Livonian mission capital of Riga, a religious order of knights, the Militia of Christ or Swordbrothers, was created by the missionary bishop c. 1202 that within a decade become co-ruler with him of Livonia and neighbouring Lettia (Latvia south of the Dvina). A few years later, a similar order, the Militia of Christ of Prussia, also known as the Knights of Dobrin (or Dobryzin), was founded at the Polish–Prussian border on the Vistula, receiving papal recognition in 1228. Unlike the Templars, whose rule they imitated, or the Teutonic Knights, these orders were parochial, tied to their local bishops, held no international property, and relied for endowment on what they could seize for themselves in the inhospitable Baltic terrain. As permanent Christian garrisons, they provided a precedent for the regional dominance established from the 1230s by the Teutonic Knights. The presence of holy warriors combined with the idea of holy space. The papacy claimed Livonia and Prussia for St Peter while the Livonian missionaries at Riga took the Virgin Mary as patron. Albert of Buxtehude, the dynamic entrepreneurial bishop of Riga (1199–1229), apparently insisted Livonia was the land of the Virgin Mary as Jerusalem was that of Christ.16 The identification with the Virgin was strengthened by the Teutonic Knights, whose patroness she was, when they ruled both Prussia and Livonia after the 1230s. The Baltic conquests were thus incorporated into a parallel transcendent narrative of defending Christian lands and proselytising the faith.

Reality challenged this narrative. Unity among the Christian conquerors was secondary to institutional and national rivalries. Danes fought the Swordbrothers and the Teutonic Knights in Livonia and Estonia. In 1234 the Swordbrothers in Riga massacred a hundred servants of the papal legate.17 Later in the century, academics such as the Oxford scholar Roger Bacon and the Dominican preaching expert Humbert of Romans even questioned the justice and efficacy of violence as a tool of conversion. The image of eternal conflict ignored processes of conquest and colonisation. While Germans and Flemings settled in Prussia in some numbers, the few westerners in remote, harsher Livonia and Estonia largely confined themselves to defensible riparian trading posts. In Prussia, faced with a repressive discriminatory regime, indigenous Balts slowly acculturated to German religion, laws and technology and over time, like the Slavs between the Elbe and Oder, became German. In Livonia, foreign settlement was largely confined to small military, clerical and commercial communities relying for survival on force and the management of local trade through control of rivers and coastal ports. This position inevitably encouraged a measure of accommodation with native rulers in pursuit of their own trading opportunities and protection. The crusades overlaid such developments, but did not create the circumstances for colonial exploitation.

Livonia, 1188–1300

The invasion of Livonia was launched through an alliance of commercial and ecclesiastical interests in Bremen and Lübeck attracted by trade and Christian mission in the increasingly prosperous eastern Baltic. The alliance was initially the work of Archbishop Hartwig II of Bremen (1185–1207), who had elevated a lone missionary station in the Dvina valley into a bishop-ric in the 1180s. Despite teaching the locals how to build forts in stone, the missionary bishop, Meinhard, achieved few converts before his death in 1196. His successor, Berthold, followed a preliminary reconnaissance in 1196–7 with a military expedition in 1198 supported by a papal grant of remission of sins from the crusade enthusiast Celestine III. Although Berthold was killed during an otherwise successful German campaign, the precedent was set. His successor, Archbishop Hartwig’s nephew Albert of Buxtehude, immediately began promoting German commercial interests as holy war and turning trading posts into a missionary state. While the project was largely a family business, Albert’s core following and main beneficiaries of the conquest formed by his and Archbishop Hartwig’s kindred, it received international political support. In a papal bull of October 1199, Innocent III offered non-Holy Land pilgrim remissions for those who took up what was branded the defence of Livonian Christians.18 Bishop Albert ignored Innocent III’s reluctance to equate the Livonian campaign with a Holy Land crusade. Unilaterally appropriating the full panoply of a crusade – cross, preaching, full remission of sins – for his enterprise, in 1199–1200 he recruited crusaders from Saxony and Westphalia and the strategically crucial mercantile community at Visby in Gotland, where five hundred apparently took the cross. He simultaneously negotiated with a potential rival, King Canute VI of Denmark (1182–1202), for safe passage to Livonia for his armada.20

HENRY OF LIVONIA

Crusading was a written phenomenon. The events of war, conquest and settlement are filtered through the interpretation contained in the texts describing them. There is no neutral witness. The Chronicon Livoniae by the German missionary priest known from his chronicle as Henry of Livonia is no exception. Despite its autobiographical tone, apparent narrative simplicity and unfussy Latin, this represented a skilfully fashioned political advocacy and religious polemic, artful in its superficial artlessness. Henry constructed a coherent creation myth that made the early thirteenth-century German conquest and settlement of Livonia (modern Latvia and Estonia) appear providential, proof of God’s immanence, a triumph of truth, faith and justice against the eternal miscreant forces of darkness and evil.

Henry (c. 1188–after 1259) came from Saxony, near Magdeburg, before education at the Augustinian monastery of Segeberg in Holstein, where Meinhard, the first missionary bishop of Livonia (d. 1196), had been a canon. As well as sound training in Latin and the scriptures, at Segeberg Henry may have acquired Estonian and Latvian from Livonian hostages sent there by the brother of Abbot Rothmar, the redoubtable Albert of Buxtehude, bishop of Riga, a connection that determined Henry’s future calling and career. In 1205, Henry joined Bishop Albert at Riga before being ordained in 1208 and assigned the missionary parish of Papendorf (near the modern Latvian/Estonian border). Henry’s proximity to Bishop Albert provided him with first-hand experience of the German conquest and Christianisation of the region and the dynamic central character in the drama that Henry’s chronicle, probably written between 1225 and 1227, unfolded.

Henry wrote an extended apologia for German invasion, conquest and military suppression of the native population. The language is heavily scriptural, much of it from the martial Books of the Maccabees, long associated with crusaders. The insistence was on the religious and canonical probity of the German occupiers confronted by the relentless perfidy and malice of the natives. Clearly aware of the canonical prohibition on forced conversion, Henry emphasised that the locals were punished for apostasising after initial free conversion or for attacking Christian communities. In Henry’s vision, the German settlement was sustained with papal grants of remission of sins equivalent to those of Holy Land crusaders, a probably deliberate distortion by Henry or his source – Bishop Albert – exaggerating papal policy and practice. Henry aimed to secure the reputation and status of the see of Riga and to promote Livonia as the land of the Virgin Mary, a site of pilgrimage and grace. While not minimising violence or suffering, Henry provides insight into various methods of conversion, from coercion, bribery and entertainment to persuasion and genuine conviction. The force of Henry’s polemic may have been stimulated by possible challenges to the Riga legend from papal legates, discontented locals or rival Danes. Henry’s chronicle fits a medieval type as a colourful and coloured creation myth and a powerfully confident account of frontier conflict, Christian conquest and cultural annexation, in this instance blessed by the cross of the crusader.19

102. A page of Henry of Livonia’s Chronicle.

Bishop Albert’s expedition to Livonia in 1200, which he and his apologists insisted on portraying as a crusade equivalent to the concurrent eastern Mediterranean expedition, set the pattern for the next twenty-five years. Bishop Albert made annual recruiting tours of Germany and the western Baltic, providing soldiers, merchants, seamen, entrepreneurs, clerics and adventurers with absolution of sins in the pursuit of profit – even though, despite a bull of 1204 allowing Holy Land vows to be commuted to service in Livonia, Innocent III continued to avoid recognising Livonia’s parity with the Holy Land. Albert’s campaigns met with success. By 1210, the coast and lower Dvina had been subdued or overawed; a capital established at Riga whose harbour could be used by large cargo round ships, known as cogs; a cathedral had been started and the Swordbrothers founded. The new settlement rested on volatile foundations. The locals treated conversion as a temporary consequence of defeat to be reversed once the Germans moved on or away. Internationally, Bishop Albert faced challenges to his sovereignty from the papacy and the king of Denmark. Internally, clerical rule depended on the support of the German merchants, whose interests were primarily economic not spiritual; for them conversion was useful as a means to bind locals to German trading practices. The Swordbrothers controlled a third of all territory and claimed rights to share future conquests. The interests of the ecclesiastical, commercial and military establishments regularly conflicted, united only by an entrepreneurial imperative to exploit the indigenous people and economy. The Christian mission imitated secular acquisitiveness in creating bishoprics and monasteries. The whole project relied on Bishop Albert’s almost annual crusades providing physical force and ideological respectability.

104. People-and-cargo-carrying cogs on the seal of the Baltic trading Hanseatic League and in the port of Riga.

The conquest of the lower Dvina valley, the Semigallians to the south and west and the Letts to the north and east, secured the Livonian coast. This allowed the Germans to protect local allies and control trade from the interior, both incentives for indigenous rulers to come to terms. Further advances between 1209 to 1218 northwards into Estonia were checked by the competing ambitions of Valdemar II of Denmark (1202–41), who built a fort on the north coast at Reval (now Tallinn) in 1219, leading to the partitioning of Estonia in 1222. The Danes dominated the sea-lanes from Lübeck, the vital entrepôt for manpower and trade without which the German Livonian enclave could not survive. Bishop Albert died in 1229. Contending interests remained: the Danes; the papacy; settlers; merchants; the Swordbrothers; local converts, allies and pagans; disturbed or hostile neighbours: the Curonians, Lithuanians and Russians of Novgorod. Internal divisions were matched by threats of rebellion and invasion. Territorial advances were balanced by fierce rivalry for land, desperate revolts by the hard-pressed peasantry (1222 and 1236), and the Swordbrothers’ increasing violence and gangsterism. Pursuing an aggressively independent military policy under Master Folkwin (1209–36), from 1225 the Swordbrothers annexed Danish northern Estonia, allied with Livonia’s enemies to acquire more territory, plundered church property, impeded baptisms and massacred converts. The Swordbrothers appeared more interested in locals as slaves not Christians, an intriguing, but not unique, attitude for a religious Order. The papacy had been scrutinising the Order for years before the massacre of the legate’s men in 1234. The death of Folkwin with fifty brothers, almost half the Order’s knights, at the battle of Saule against the Lithuanians in 1236, provided the opportunity the following year for the transfer of the remnant of the Order, its prerogatives and property, to the equally violent but more orderly Teutonic Knights.

105. Conquest: Turaida Castle, begun by Bishop Albert of Riga in 1214.

The Teutonic Knights reshaped Livonia. They ended the awkward duopoly with the Rigan Church; mended relations with the papacy and the Danes (restoring Estonia to them in 1238); and used diplomacy as well as force to pacify neighbours. Hardly eirenic in dealing with internal opposition, their wider resources helped the Order overcome revolts and resistance from satellite provinces. From the late thirteenth century, the Teutonic Knights imposed security for the German settlement by creating a depopulated scorched earth cordon sanitaire in Semigallia that protected Livonia from Samogitia and Lithuania. The consequent struggle with Lithuania dragged into the fifteenth century. Ruling an autonomous province within the Order, with its own Master answerable only to the Grand Master based after 1309 in Prussia, the Livonian Teutonic Knights survived until 1562, when the last Livonian Master made himself duke of Courland and Semigallia.21

Danish and Swedish Crusades

Territorial ambitions of Scandinavian kings were linked to efforts to elevate their internal as well as foreign status through alliance with the international Church. While the crusade provided a suitable context, motives for conquest were material: to police piracy, exploit maritime trade and manipulate access to valuable raw materials. So were the means: raiding, a sort of counter-piratical piracy, and planting combined religious and trading stations, a continuation of the Viking tradition under the flag of Christ. Church approval of wars of conquest supplied ideological gloss for existing habits. In the twelfth century, the Danes fought the Wends and other pagans in the southern Baltic, while their fleets penetrated eastwards in pursuit of increasing regional trade. Swedes started to harry the shores of the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga. Such aggression against non-Christians traditionally gained ecclesiastical support. When an attack on non-Christian pirates led by the Danish Archbishop Absalon of Lund (1178–1201), a vigorous pagan-basher, was described as ‘making an offering to God not of prayers but of arms’, this was not an account of a crusade, but a reflection of a far older tradition of war against the pagans deo auctore; as was a promise of heaven to those who died fighting pagans in defence of the Norwegian patria made during a royal synod held at Trondheim (1164).22 Nonetheless, by presenting such wars as extending or defending Christianity, papal approval could be sought, enhancing regal image.23 Alexander III’s 1171 offer to Valdemar I of Denmark of a year’s Holy Land plenary indulgence to participants on an expedition against pagans in the eastern Baltic, probably the Estonians, and a full remission for those who died on campaign, while lacking the full crusade apparatus of vow, cross, preaching and temporal privileges, confirmed available justifications and incentives.24

Yet, however much Valdemar I was a devotee of holy war against pagans, no Danish crusade to the eastern Baltic occurred until 1206 when, according to the not always reliable chronicler Henry of Livonia, the troops accompanying Valdemar II’s raid on the island of Osel were given the cross by the archbishop of Lund.25 The Danish invasion of northern Estonia in 1219–20, in coalition with the Swordbrothers and King John I of Sweden (1216–22), was backed by a papal crusade bull. The Swedes briefly occupied Leal on Estonia’s west coast while the Danes built a fort overlooking Reval’s large natural harbour. Thereafter, the Danes acted as absentee landlords, taking profits from trade and land as the new town at Reval was settled chiefly by Germans. Danish overlordship was recognised by the Teutonic Knights (1238). Further Danish conquests eastwards provoked confrontation with the Russians of Novgorod, branded hostile schismatics by successive popes who provided crusading support for campaigns against them in the hope of further converts in the pagan lands of the eastern Gulf of Finland. The results were meagre. Valdemar II joined the Teutonic Knights and Swedes from Finland in the disastrous anti-Russian crusade of 1240–2 that saw defeats for the Swedes on the River Neva in 1240 and for the Teutonic Knights at Lake Chud-Peipus on 5 April 1242; Alexander Nevsky of Novgorod’s victory received vividly iconic if fanciful reworking in Sergei Eisenstein’s famous patriotic 1938 film. Eric IV of Denmark’s (1241–50) taking the cross in 1244 led nowhere. A fresh crusade in 1256 to the lower Narva failed to achieve converts. Danish interest in the eastern Baltic waned; in 1346, Danish Estonia was sold to the Teutonic Knights.

106. The Battle on the Ice, 5 April 1242.

Increasingly only the Swedes, already established on the Gulf of Finland, seemed attracted to further military action in the bleak unproductive area further east where material returns were exiguous and conversion hardly a priority. Swedish incursions into Finland began in the twelfth century, later accompanied by missionary attempts. After some success in south-west Finland, resistance became stiffer further east in Tavastria where the Swedes confronted the neighbouring Karelians and Novgorod Russians in wars that lasted into the fourteenth century. Crusades were attached to Swedish expansion into eastern Finland, in 1237, 1249, 1257 and 1292. Appropriate histories of Swedish martyrs and a saintly royal holy warrior, Eric IX (1156–60), were invented retrospectively. Holy war was urged on Magnus II (1319–63) by his cousin, St Bridget, conveniently as a legitimate excuse for royal taxation.26 Magnus, supported by another crusade enthusiast, Pope Clement VI (1342–52), responded with two crusades (1348 and 1350) against the Russians that achieved little. A subsequent papally backed scheme in 1351 produced rich tax pickings from a church tithe which, in the absence of any military action, the papacy demanded be paid back. Later efforts to drum up support for an anti-Russian crusade by King Albert (1364–89) failed. Ideas for crusades still circulated into the late fifteenth century as Karelian raiding continued, but the last Swedish crusade bull in 1496 never even arrived, confiscated in transit by King John of Denmark (1481–1513). Although Swedish rule of Finland lasted until 1809, the role of the crusade in its beginnings was insignificant.

Prussia

By contrast, crusading created German Prussia. Through conquest and rule from the 1220s, the Teutonic Knights built an unprecedented Ordenstaat, a state run by a Military Order, a polity to which the Livonian Swordbrothers had aspired but failed to realise. Polish rulers, eager for greater access to the Baltic, had campaigned against the Prussians throughout the twelfth century in wars that, at least in retrospect, were afforded a gloss of quasi-crusading holiness; one early thirteenth-century Polish chronicler even described the Prussians as ‘Saladinistas’.27 However, it was only in 1217 that a crusade bull was issued on behalf of a mission to the lower Vistula valley by Bishop Christian (1215–45), supported by German and Polish lords. The failure of their efforts, confronted by local resistance, led in 1225 to an invitation from the Polish Duke Conrad of Mazovia to the Teutonic Knights to intervene. Since 1211, the Knights had been serving King Andrew of Hungary in Transylvania against the Cumans. In 1226 their Master, Hermann of Salza (1209–39), a sharp political operator and close associate of Emperor Frederick II, secured an imperial bull authorising the Order’s invasion of Prussia. Any conquests in Kulmerland and Prussia were to be held by Hermann as a Reichsfürst, an independent imperial prince. Conrad of Mazovia abandoned his role as patron of the enterprise. In 1234, Hermann secured the additional protected status of papal fief for the Order’s Prussian lands. The removal into Prussian captivity of Bishop Christian (1233–9) left the Order without rivals, a position consolidated by Innocent IV’s delegation to it in 1245 of the power to call and recruit crusades without prior papal consent.28 The Order thus became the arbiter of its own fate, sole political authority in Christian Prussia, and manager of any future crusades there.

The conquest of Prussia began in 1229 with the Teutonic Knights’ deployment of a small garrison in the upper Vistula. This allowed the invaders to interrupt Prussian trade in the interior, enabling easy access to home bases and recruits via Poland and Pomerania. Proximity made Prussian crusades more popular than those to distant Livonia and among German nobles even usurped the Holy Land as the crusade destination of choice.29 Once again, campaigns focused on rivers, with forts and trading posts used to control and exploit conquered territory. The invaders’ technological superiority and land frontier further secured their advantages during the advance down the Vistula towards the Baltic and the Frisches Haff which, with aid from regular crusading armies recruited mainly from across eastern Europe, was reached by 1237. As well as estates granted to German lords, the conquest rested on a network of forts built by the slave labour of the conquered: Thorn (1231); Marienwerder (1233); Reden (1234); the tellingly named Christburg (1237); Elbing (1237). The Knights soon attracted Dominican preachers and German settlers, drawn by special civil privileges: Silesians in Kulmerland; citizens of Lübeck in Elbing. Further advances in the late 1230s towards Samland and the Order’s recently acquired Livonia threatened to deny indigenous Prussians access to the sea, thereby completing Latin Christian control of the Baltic seaboard.

The Military Order’s early successes provoked a decade-long revolt from the Prussians aided by a fearful and jealous Duke Swantopelk of Danzig. Beginning in 1242, the rebels, using guerrilla tactics to neutralise the Germans’ heavy cavalry and crossbows, soon swept aside the Order’s conquests except in Pomerania and a few isolated outposts such as Elbing. The Order’s response combined renewed commitment to war and local reprisals. The so-called treaty of Christburg (1249) offered Prussian converts, chiefly aristocrats, civil rights under the jurisdiction of church courts, in other words obedience to the Order. The consequent emergence of an elite of Christianised Prussians provided a new buttress to the German regime. Pagans were cast beyond the rules and protections of civil society. Such limited accommodation extended to diplomacy. In 1253, to forestall Polish intervention along the Vistula, a deal was struck with Duke Swantopelk. King Ottokar II of Bohemia assisted the annexation of Samland (1254–6) to blunt the ambitions of Lübeck and of Hakon IV of Norway, who had been promised it by the pope. Even King Mindaugas of Lithuania (1236–61) was induced to convert and ally with the Order as protection from the Russians, allowing the incorporation of Samland and the construction of Memel (1252) and Georgenburg (1259).

These successes were immediately thrown into hazard by a well-organised general Prussian rising in 1260 supported by Swantopelk’s son Mestwin of Danzig. Limited acculturation had lent the Prussians German military technology: crossbows, siege engines and field tactics. Between 1260 and 1264 two of the Military Order’s Prussian Masters were killed; a crusade was destroyed at Pokarvis near Königsberg; forts were overrun; settlers massacred. Savagery in the name of faith was mutual; devastation and displacement of people extensive. The Order survived through regular assistance from large, well-funded crusade armies. By 1283, with the surrender of the Yatwingians, the Prussian tribes had been subdued or annihilated. The Coronians, Letts and Semigallians were conquered by 1290. Revolts in 1286 and 1295 failed to loosen the Order’s grip. Opponents were left with the choice of slavery or exile. The Prussian Ordenstaat emerged as a regime in its own right: enclosed, brutal, exploitative, defined by God and the sword.

Recruitment for the crusades that saved Prussia for the Teutonic Knights far outstripped that for the Livonia wars. The 1230s saw Polish nobles, German princes; townspeople from Silesia, Breslau, Magdeburg and Lübeck; minor lords from Saxony and Hanover. Leading German princes soon followed: Rudolph of Habsburg (1254), Otto III of Brandenberg (1254 and 1266); Albert I of Brunswick and Albert of Thuringia (1264–5); and Dietrich of Landsberg (1272). Ottokar II of Bohemia (1254–5 and 1267) gave his title to the new castle of Königsberg. Some recruits may have used these crusades to escape the political dilemmas thrown up by extended German civil wars from the late 1230s. The Military Order’s skilful diplomacy maintained relations with both warring parties of pope and emperor, securing its own independence and soothing papal doubts over the Order’s increasingly notorious activities. As well as defeating the Prussians, the Order contained or repelled other challenges to its monopoly of power. Besides incorporating the Livonian Swordbrothers in 1237, the Order absorbed Bishop Christian’s Militia of Dobryzn in 1235 while their patron was in Prussian captivity. In 1243 the new Prussian episcopacy was reduced in size, jurisdiction and share of new possessions.30 After a failed coup in Livonia in 1267–8, the legate Albert Subeer (archbishop of Prussia 1246–53 and of Riga 1253–73) even spent a short time imprisoned by the Order. Innocent IV’s devolution to the Order of the authority to call crusades in 1245, while not eliminating papal appeals and preaching campaigns, provided the Knights with the means to pursue their wars as crusade at will, a privilege extended in 1260 by Alexander IV’s mandate for the cross to be preached by the Order’s own priests.31 These arrangements gave the Order free rein, the crusade forming an integral element in military policy and the rhetorical projection of the Knights as champions of the faith.

The Later Middle Ages

Frontier wars and military aggression, frequently in the guise of crusades, did not cease with the consolidation of the Military Order’s control within Prussia, Livonia and southern Estonia. Encouragement of trade and German – ‘New Prussian’ – immigration prompted attempts to expand control over the whole southern and eastern Baltic. Besides the purchase of north Estonia in 1346, Danzig and eastern Pomerania were annexed in 1308–10. In 1337, Emperor Louis IV of Germany invited the Order to conquer pagan Lithuania and its Christian Polish allies, the crossed-wires of Baltic politics finding Poles both as allies of pagan Lithuania and, in papal eyes, potential crusaders against them. Additional incentive for continued crusading militarism came from the Order’s precarious international status following the fall of the last mainland outpost of Outremer in 1291. Despite ruling Prussia, the Order initially maintained its Mediterranean base, moving its headquarters to Venice, an indication of the continuing importance of its Mediterranean origins. Events subsequently forced a change. The violent suppression of a rebellion against the Order by the archbishop, clergy and citizens of Riga in 1297–9 led victims to appeal to the pope, feeding growing disquiet in some quarters at the Order’s general behaviour in the Baltic. Although retaining vociferous supporters, such as Bishop Bruno of Olmutz who wrote in laudatory terms for Pope Gregory X in 1272, persistent complaints led Clement V (1305–14) to instigate an inquiry in 1310 into the Order’s methods and performance. The Livonian brothers were briefly excommunicated in 1312. Fortuitously or not, this coincided with new attacks on Livonia and Prussia by the pagan Lithuanian Grand Prince Vytenis. Even more immediately, the whole function and legitimacy of Military Orders, the subject of academic debate for a generation, were cast into jeopardy by the arrest and trials of the Templars, beginning in 1307–8, culminating in their suppression in 1312. To avoid scandal and escape from harm’s way while simultaneously polishing their credentials as holy warriors, just as the Hospitallers responded by supervising the occupation of Rhodes (1306–10) and moving their central Convent there in 1309, so in the same year the Teutonic Knights established their headquarters at Marienburg.

The fourteenth-century crusades against Lithuania provided ideological cover for the Military Order’s power, justifying its privileged international status and attracting military recruits. At its largest, alone the Order’s knights only numbered about 1,000 to 1,200 divided between Prussia and Livonia. Regular winter and summer Reisen (raids) against Lithuania, until 1386 a pagan power, sustained the tradition of meritorious religious war for a European aristocracy increasingly embroiled in unequivocally secular conflicts such as the Hundred Years War. Although conditions across the wilderness between Prussia/Livonia and Lithuania were consistently grim – frozen in winter and waterlogged in summer – foreign nobles could take the opportunity (and risk) to show off in difficult and often dangerous combat. Conversion of the enemy was not an issue. With stalemate with Lithuania prevailing, Reisen assumed features of chivalrous grand tours, decked with feasts, heraldry, souvenirs and prizes. These attracted clients from western Europe, beyond Germany or central Europe. While part of a dour violent struggle for power and profit, Reisen ostentatiously incorporated recruits’ cultural aspirations, as in 1375 under Grand Master Winrich of Kniprode (1352–82), when selected nobles received badges with the motto ‘Honour conquers all’, despite its stark crusading incongruity. Baltic Reisen proved particularly attractive during truces in the Hundred Years War in the 1360s and 1390s.

107. Marienburg Castle.

Between 1304 and 1423 the bulk of recruits came from Germany, although many came from other regions. Some campaigned many times: John of Luxembourg, king of Bohemia, William IV count of Holland and the Frenchman Marshal Boucicaut three times each; William I of Gelderland on seven occasions between 1383 and 1400. Summer campaigns could be substantial: in 1377, Duke Albert III of Austria brought 2,000 knights with him. At least 450 French and English nobles made the journey over the century, so Chaucer’s Knight became a familiar type:

Ful ofte time he hadde the bord bigonne

Aboven alle nacions in Pruce;

In Lettow hadde he reysed, and in Ruce,

No Cristen man so ofte of his degree.32

English evidence confirms the extended social networks involved.33 Anglo-French peace in 1360 prompted relatively large-scale plans and expeditions, notably one led by the earl of Warwick. However flamboyant, such commitment was not necessarily light-hearted. The reality of combat, injury and death elevated the enterprise beyond the merely self-serving or ludic. The Marienkirche in Königsberg acted as a mausoleum. The experiences of recruits linked the Baltic crusades with other theatres of war against the infidel: Marshal Boucicaut, Humphrey Bohun earl of Hereford and Richard Waldegrave, a future Speaker of the English House of Commons (1381), each fought in the Mediterranean as well as against the Lithuanians. In 1365, Pope Urban V saw Thomas Beauchamp, earl of Warwick’s vow as applying equally to Prussia or Palestine.34 Although it is difficult to determine whether those who fought with the Military Order had ceremonially taken the cross, the trappings, language and perhaps the emotions of religious war remained as the knights continued to proclaim their Reisen as crusades. Recruits such as Henry Bolingbroke, the future Henry IV of England, visited Prussian shrines offering indulgences. Despite the growing gap between military strategy and religious purpose, the popularity of the Baltic campaigns emphasised the tenacity of crusading tradition while the Order restricted foreigners to military assistance alone. In alliance with the Hanseatic League, the Order resisted external penetration of its markets, negotiated tight trading concessions, fought over control of fish stocks, and exacted heavy fines for trading irregularities.35

The Military Order’s success in Prussia and Livonia contrasted awkwardly with the failure of the Lithuanian crusades. Generations of war produced no resolution; Prussia remained German and Lithuania independent. In 1386 the political and religious context radically altered when Jogaila of Lithuania (1377–81; 1382–1434) became king of Poland (1386–1434) and converted to Christianity, calling into doubt in some minds the very legitimacy of Baltic crusading, the Order’s purpose and its rule in Prussia/Livonia. Still employing traditional crusading rhetoric, the Order, with some success, sought foreign allies to unpick the Lithuania and Poland alliance. With larger contingents even than in the 1360s and 1370s, the Order made ground: Dobryzn in the 1390s and Samogitia between 1398 and 1406. This aggressive policy came to a disastrous end with the Lithuanian-Polish victory at Tannenberg/Grunwald (15 July 1410) at which Grand Master Ulrich von Jungingen, most of the Order’s high command and 400 knights were killed. Although territorial losses were modest, a brief revival of international aid after Tannenberg soon waned, perhaps because the Hundred Years War restarted in 1415. It seems that non-Germans ceased to campaign in the Baltic after 1413, concluding a trend apparent before Tannenberg. After 1423, even the Germans stayed away.

108. The reconstructed Königsberg/Kaliningrad Cathedral.

109. The battle of Tannenberg, 1410.

Tannenberg exemplified the problem: a Christian army defeated by another Christian army. The Council of Constance (1414–18) that healed the Great Schism (1378–1417) debated the Order’s future. Although rejecting radical criticisms and refusing to censure the Order, in 1418 the Council declined to approve the Order’s request for a new crusade against its enemies. Tellingly, the new pope, Martin V (1417–31), made the rulers of Poland and Lithuania his vicars-general for a planned war against the schismatic Russians. The whole basis for continuing crusading against Lithuania-Poland collapsed, along with the Order’s reputation and credentials. With the last foreign crusade to Prussia ending in 1423, the Order’s power declined, undermined internally by competing landed and civic interests and externally by a resurgent Poland. A Thirteen Years War (1454–66) unpicked the Order’s dominance. At the Treaty of Thorn in 1466, west Prussia, including the Order’s seat at Marienberg and most of the earliest conquests dating back to the mid-thirteenth century were lost, leaving only an eastern rump. The Grand Masters in their new capital at Königsberg were now little more than Polish clients.

Holy war was not wholly abandoned. In 1429 a detachment of Teutonic Knights fought the Ottoman Turks for Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor and king of Hungary. In Livonia the interminable struggle with the Russians continued. However, popes, not averse to allowing crusades elsewhere, refused to assign crusades to the Order’s wars. Between 1495 and 1502, Alexander VI consistently rejected Livonian appeals for a crusade against the Russians. Although technically able to authorise crusades themselves, the Order unavailingly sought international support. The Baltic crusades had helped turn the Baltic region Christian. Regional demography, economy, even flora and fauna, had been fundamentally changed in one of the most radical, harsh and extensive colonial transformations in Europe since the barbarian invasions.36 Once the process had achieved maturity, the justification for further crusades became harder to sustain. Now they ended. In 1525 the Prussian Order secularised itself. In 1562 the Livonian convent followed suit.