THE END OF THE JERUSALEM WARS, 1250–1370

The failure of the Egyptian crusade of 1248–50 could not be reversed. The succession of aggressive Mamluk sultans in Egypt bent on proving their Islamic credentials made conquest of enfeebled Frankish Outremer a clear objective once the immediate threat of Mongol lordship in Syria had receded after the Mamluk victory at the battle of Ain Jalut in 1260. Thereafter, Outremer survived through piecemeal treaties and increasingly desperate and ineffectual military and diplomatic expedients. Louis IX could do little more than follow the pattern during his stay at Acre between 1250 and 1254: shoring up the defences of Outremer’s remaining cities and castles; futile diplomacy, such as the abortive treaty with Egypt in 1252 against Damascus or pursuing contacts with an indifferent Mongol Great Khan; and funding modest garrisons at Acre after his departure. In the west, since the 1230s, competing threats, such as the Mongols, or distracting alternative opportunities, such as crusades with the Teutonic Knights in the Baltic, against supposed religious dissidents or even papal crusades against the Hohenstaufen, may have blunted active engagement with the Holy Land and provoked criticism.1 However, especially in Italy and France, generalised enthusiasm for the original cause continued to resist strategic reality, the concept of divine retribution for sin providing cover for logistical contradictions that three generations of planners, theorists and lobbyists sought and failed to unravel. Ideas for Eurasian alliances, maritime blockades, economic embargos, fiscal innovations and professional armies regularly reached the council chambers of rulers whose lip service to the Holy Land failed to override domestic political obligation, a dilemma appreciated by the veteran crusader John of Joinville when he condemned Louis IX’s crusade to Tunis in 1270 as damaging to the peace and security of France.2

The Shepherds’ Crusade, 1251

A striking illustration of Joinville’s dilemma came with the so-called Shep-herds’ Crusade in France during 1251, which exposed the impotence of popular enthusiasm and the perils of absentee rulers. News of Louis IX’s defeat and capture reached western Europe in the summer and autumn of 1250, provoking disturbances in Italian cities and outpourings of communal grief in France. By the spring of 1251 people in rural Brabant, Flanders, Hainault and Picardy, described slightingly as ‘shepherds and simple people’, mobilised with the stated intention of travelling to join Louis in the Holy Land.3 Echoing the 1212 Children’s Crusade in criticising the crusade failings of the nobility, disparate groups of pastoureaux (shepherds) across northern France parodied the crusade processions familiar since the early thirteenth century. Some marched on Paris carrying banners with symbols of the Passion (including the paschal lamb that may have provided their nickname) and the Virgin Mary, while handing out crosses and absolution of sins. Far from an inarticulate formless rabble, they were initially supported by the Regent, Blanche of Castile (d. 1252). Some may have actually reached the Holy Land, indicating means beyond those of shepherds.4 Demonstrations, expressing social frustrations as well as crusade enthusiasm, spread from Normandy to the Loire and south into Berry and beyond. Degenerating into armed gangs, they provoked violence in Rouen, Orléans and Bordeaux, particularly directed at clerics. At Bourges, one band, led by an educated man called ‘the Master of Hungary’, allegedly trilingual in French, German and Latin, attacked Jews before being dispersed and their leader killed.

While, for the mass of followers, the uprisings led nowhere, they demonstrated significant popular acquaintance with official policy and high politics: the use of crusading symbols, such as images of the Passion, favoured by King Louis himself; indulgences; cross-giving; the desire for government approval; criticism of the nobility and clergy; predatory hostility towards Jews, another royal habit; and the call for political action in the service of God. Clerical accusations of disorder, criminality and sexual excess concealed the movement’s coherence and the popular resonance of targets such as venal clergy, feather-bedded scholars and Jews. Of varied economic status, the ‘pastoureaux’, proclaiming loyalty to the king, expressed the frustrations of the marginalised not the ignorant. They revealed wide social diffusion of crusading practices and mentalities achieved through preaching, communal ceremonies, taxation and gossip. Like their social superiors in the Nile Delta, they also showed how devotion alone was not enough, a fact confirmed by Louis IX’s crusade to Tunis in 1270.

The 1270–2 Crusade

Louis IX did not abandon Outremer after 1254. He provided for a French garrison at Acre and annual subsidies. At home, he fashioned an image of royal asceticism and Christian devotion, for which his sufferings in Egypt provided unimpeachable witness, the commitment to the Holy Land supporting a programme of moral authority crafted in art, architecture, anti-Semitism, religious observance and politics.5 Charles of Anjou’s victory in southern Italy and Sicily (1266–8) and the triumph of the royalists in the English Civil War (1263–7) freed Louis to try reversing the verdict of 1250. By September 1266, partly in response to worsening news from the Holy Land, he was planning to take the cross once more.

The survival of Outremer was in increasing jeopardy. The arrival of the Mongols had transformed the regional balance of powers. After capturing Baghdad and killing the last Abbasid caliph in 1258, the Mongols conquered Syria in early 1260, briefly occupying Sidon and raiding as far as Gaza.6 Bohemund VI of Antioch-Tripoli (1252–75) submitted to Mongol overlordship, accepting a Mongol garrison in Antioch that remained until 1268 when the city fell to the Mamluks. Armenian Cilicia also accepted Mongol overlordship. By contrast, the Franks of Acre refused to ally with the Mongols but equally declined to assist the new Mamluk sultan of Egypt, Qutuz, against them. Given Mamluk hostility and the Mongols’ uncompromising unilateral approach to alliances, this may have appeared prudent. However, both Acre and Tripoli-Antioch were left vulnerable after the Egyptian victory at Ain Jalut in southern Galilee (3 September 1260) over a modest Mongol force left behind when the main army had withdrawn eastwards. With Mongol attention subsequently focused on Iraq, Iran and the Caucasus, the Mamluks rapidly proceeded to annex Muslim Syria, ejecting or overawing the surviving Ayyubid princes. By the end of October 1260 when the Bahriyya Mamluk commander Baibars (1260–77) assassinated Qutuz and assumed the sultanate, the unification of Egypt and Syria was more complete than at any time since 1193.

119. Hulagu captures Baghdad, 1258.

Baibars, who had played a central role in the Egyptian military campaigns and internal violence of 1249–50, now used the conquest of Outremer to cement his political and ideological authority, in the process denying the Mongols a potential ally. From 1265 he proceeded to dismantle the remains of Outremer through asymmetrical diplomacy and irresistible siege warfare: Caesarea, Arsuf, Toron and Haifa fell in 1265; Safed, Galilee, Ramlah and Lydda in 1266; Jaffa, Beaufort and, with a punitive massacre, Antioch in 1268. Baibars’ aggression provoked Pope Clement IV to revive crusade plans begun in 1263 under his predecessor Urban IV. On 25 March 1267, the Feast of the Annunciation, before the relics of the Passion in the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, Louis IX took the cross with his immediate family and the leading magnates in France.7

The 1270 crusade was expertly organised. Repeating techniques familiar from the 1240s, finance came from a French clerical tithe, legacies, redemptions, taxes on towns and tenants, expropriation of Jewish funds and sales of private assets. Ships were commissioned from Genoa, Marseilles and ports in Catalonia. As in 1248–9, the king underwrote the expenses of leading companions, including the duke of Burgundy and the counts of Poitiers, Champagne, Brittany and Flanders. English and Gascon involvement was attracted by loans of 70,000 livres tournois to Louis’ English nephew, Edward, the future Edward I. As well as the usual recruiting devices of kinship, lordship, friendship and geographic association, formal contracts were issued on both sides of the English Channel specifying pay and other rewards for a stated number of knights: Louis paid for a contracted core of 325 knights; Edward paid for one of 225. In total, a combined force of between 10,000 and 15,000 could have been assembled. Beyond France, recruits came from Frisia, the Netherlands, Aragon, Scotland, England and the kingdom of Sicily, now ruled by Louis’ brother, Charles of Anjou. Louis secured the adherence of James I of Aragon. In England, Edward and his brother Edmund took the cross in 1268; in 1270 they managed to extract a parliamentary tax on moveables of a twentieth, perhaps worth £30,000, the first lay subsidy granted to the English crown since 1237.8

120. Baibars and his court.

Yet, despite central contracts and royal funding, the new crusade was a disjointed affair. Louis planned to depart in May 1270 and did so in July; James of Aragon had embarked in June 1269; Charles of Anjou only took the cross in February 1270, starting to equip his fleet in July when his brother was already at sea en route for Tunis; Edward only set out from England in August 1270, arriving at Tunis in November just as the crusaders were packing up to leave; and his brother Edmund did not set out until the winter of 1270–1. Storms wrecked the Aragonese fleet, only a few ships reaching Acre. Recruitment in France fell short of initial estimates. The long papal interregnum from the death of Clement IV in November 1268 to the election of Gregory X in September 1271 exactly coincided with final preparations and the campaign itself. In 1268 or 1269 the original French plan for direct aid for the Holy Land and another assault on Egypt was replaced by a scheme to attack Tunis, confusingly an ally of the king of Aragon. Despite the declared muster ports in Sardinia and western Sicily, the fiction of an eastern objective was maintained, the public announcement of Tunis as the destination only coming after Louis had embarked in July 1270.

As a staging post for an invasion of Egypt, Tunis may have appeared more convenient than Cyprus. Commercial and diplomatic relations between western Mediterranean Christian powers and the emirs of Tunis were of long standing, alternately of alliance, competition and conflict. A Tunisian embassy was in negotiation with Louis in 1269, while Louis’ Dominican contacts may have argued that Tunis and north Africa were ripe for evangelism, a common optimistic mendicant trope in this period. Although possibly suiting the Sicilian ambitions of Charles of Anjou, Louis’ decision may have owed more to a combination of a mendicant-inspired commitment to convert non-Christians, a vague strategic hope of denying Egypt an ally, and securing the north African route to attack the Nile that had been suggested since the early twelfth century. The Tunis crusade reflected lasting networks of contact, commerce, competition and exchange between the powers around the western Mediterranean that belied any two-dimensional model of religious conflict.

Louis’ departure followed the precedents of 1147, 1190 and 1248, with the king receiving the oriflamme and pilgrim’s scrip and staff at St Denis (14 March 1270), and that of 1248 with him setting out from Paris as a barefoot penitent. Immediately things went wrong. At Aigues Mortes, commissioned ships arrived late and illness broke out in the army. After a stormy passage from Aigues Mortes to Sardinia (2–4 July), Louis, unsure of where he was, is said to have been shown a map of Cagliari and its situation, probably a Genese portolano, or navigational map, the first recorded instance of a crusader consulting a map or chart on campaign.9 After Tunis was revealed as the destination on 13 July, the French fleet made landfall on 17 July, the troops disembarking the next day before moving camp to Carthage a few miles away on 24 July to be nearer adequate water. Apart from some perfunctory skirmishing, operations stalled while the army waited for Charles of Anjou. Heat, poor food and dire sanitation soon sparked disease, typhus or dysentery, which ravaged the high command as well as the mass of the army. Louis (25 August 1270) and his son John Tristan (born at Damietta in the dark days of 1250) died; the king’s eldest son and successor Philip III fell seriously ill. When Charles of Anjou arrived in late August and assumed command, he had little option but to negotiate a withdrawal. With the Hafsid emir Mohammed eager to pay the crusaders to go away, terms were agreed (1 November) including an exchange of prisoners, agreement to allow Christian worship and evangelising in Tunis, and payment of 210,000 gold ounces (c. 500,000 livres tournois) of which Charles claimed a third. The crusaders, now reinforced by Edward of England, sailed for Sicily where a storm (15/16 November) destroyed dozens of ships and claimed over 1,000 lives. Thereafter, only Edward wished to continue to Acre. The convalescent Philip III returned to France with the remains of his father, brother, brother-in-law, wife and stillborn son. In Tunis, trading relations were soon restored with Sicily, Aragon and the Genoese.

The Tunis campaign, in a traditional crusading perspective a disaster, tested but failed to break the resilience of the ideal. Louis’ death in August 1270 provided the crusade with a popular martyr, even if, when canonised in 1297 it was as a confessor, to his friend Joinville’s annoyance. In 1271 the cardinals elected the well-connected archdeacon of Liège, Tedaldo Visconti, as pope (Gregory X, 1271–6), while he was in Acre on crusade with Edward of England. His attempts to recruit western rulers to a new eastern expedition culminated in the Second Council of Lyons (1274).10 Meanwhile Edward, ignoring appeals to return home where his aged father Henry III was nearing death, sailed to Acre in the spring of 1271 with a small force, possibly only 1,000 strong, carried in thirteen ships, arriving on 9 May 1271. He remained for a year, being joined in September by his brother Edmund. Edward’s stay was little more than a morale-boosting promenade. He largely avoided the traps of local Frankish infighting but, apart from helping see off a Mamluk attack on Acre in December 1271 and a couple of raids into Acre’s hinterland, contributed nothing to alleviate Outremer’s predicament. His diplomatic links with the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia proved typically nugatory. Baibars had captured Crac des Chevaliers in April 1271 and was hardly deflected from his grand design: his emollient May 1272 truce with the Franks ignored Edward’s presence. Edward’s followers, including his brother Edmund (May 1272), began leaving. The famous attempt on Edward’s life by a Mamluk assassin in June provided the most memorable incident of his Holy Land crusade, which ended when Edward sailed from Acre in October 1272 leaving behind a small English garrison and a mountain of debts. Although Edward’s quixotic crusade had cost a vast sum (perhaps more than £100,000) for no concrete achievement, in terms of fame and honour the investment paid handsomely: for the rest of his life as King Edward I (1272–1307), with the Holy Land’s fate an inescapable feature of western diplomacy and public discussion, he remained the only western monarch who had actually been there to fight for the cross, a status he reinforced by taking the cross again in 1287.

The Loss of the Holy Land

Despite statements of intent, Edward I never returned east. By pleading, not entirely disingenuously, pressing business at home, he exposed a central contradiction in attempts to rescue or restore Outremer. The application of the resources of kingdoms to crusading had shown, in 1248–50 and 1270 as in 1188–90, how costs and administration could be covered. However, the more powerful monarchs became, the more extensive their domestic obligations. Expanding bureaucracies ensured that the huge expenses of Holy Land crusades were now dauntingly measurable: the financial accounts of Louis IX’s crusades were still being examined in the 1330s.11 Extensive discussion of practical problems provoked by repeated failure inspired ideas such as the amalgamation of the Military Orders to achieve economies of scale, but inevitably tempered political enthusiasm. Before the Second Council of Lyons (1274), Gregory X collected advice and information. This revealed the scale of the challenge and, equally inconvenient, the largely negative impact exerted by the diverse theatres of crusading on the Holy Land enterprise.

Gregory X was committed to the relief of the Holy Land. On his election he preached to the text ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning’ (Psalm 137:5). The council he summoned to consider church reform and a new crusade, to be led by the pope himself, met at Lyons in May 1274. Armed with written and oral advice from a wide range of interested parties, the council produced the most complete programme for planning a new crusade yet achieved. The decree Constitutiones pro zeli fidei (18 May 1274) authorised indulgences, a trade embargo, a sexennial ecclesiastical tithe, and a voluntary lay poll tax. The collection of the church tax was organised into twenty-six collectories. Diplomatic provision included the council’s reception of Mongol ambassadors and a proposed union between the Roman and Greek Orthodox Churches negotiated with the Greek emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus (1261–85), part of his efforts to parry the Balkan ambitions of Charles of Anjou. Only in 1261 had Michael expelled the westerners from Constantinople, but he now needed allies against this new Mediterranean power. Yet only one western monarch attended, the veteran James I of Aragon, and even his offer of 500 knights and 2,000 infantry came to nothing. Following the council, preaching was authorised in September 1274 and Philip III of France, Charles of Anjou and the new king of Germany, Rudolf of Habsburg, took the cross in 1275. Large sums were raised, a departure date was fixed (April 1277), a papal fleet planned. Yet concerted political will was absent, as speakers at Lyons had warned.12 Impressive papal administrative reach failed to translate into action. The indifference of the Military Orders at Lyons spoke loudly. Gregory X’s crusade died with him in January 1276. The crusade tithes were redirected to papal crusades in Italy. Despite continued diplomacy, the Mongol alliance remained illusory. Church union foundered on rejection by the Greek Orthodox faithful. A pattern was set, copied in varying detail after the Council of Vienne (1311–12), in the 1330s and in the 1360s: papal or royal initiatives; public endorsement; diplomacy, fund-raising, administrative preparations; then delay, distraction and cancellation. As the Italian Franciscan commentator Salimbene of Adam remarked: ‘it does not seem to be the Divine Will that the Holy Sepulchre should be recovered’.13

By 1272, mainland Outremer had been reduced to a few castles and ports. Despite Christian bases in Cyprus and Cilician Armenia and maritime superiority, recovery was stymied by western inertia and Baibars’ systematic destruction of the harbours and coastal cities he had captured. The pause in attacks after Baibars’ 1272 treaty with the Franks followed by his death in 1277 combined with continuing Mongol ambitions in Syria to distract the Mamluks and delay Outremer’s final collapse. With the defeat of the Mongols at Homs in 1281 and the death of Abaqa, the expansionist Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, in 1282, Sultan Kalavun (1279–90) was given a free hand. Marqab fell in 1285; Latakia in 1287; and Tripoli in 1289, after 180 years of continuous Frankish rule, accompanied by a massacre and the demolition of the city’s defences. Although Acre still received aid, men and money, visiting crusaders, with their modest military entourages, and western-funded garrison troops could only observe, not counter the approaching end. Attempts by Charles of Anjou (1277–85) to absorb the kingdom of Jerusalem into a trans-Mediterranean empire exacerbated factional contests within Acre, while the War of the Sicilian Vespers from 1282 destroyed prospects of a united western crusade. Philip III of France died on crusade in 1285, but against Aragon not Egypt. Edward I was occupied with conquering Wales (to 1284) and the Scottish succession (from 1290). German involvement was compromised by the divisions left by the imperial interregnum (1250–73). After Charles of Anjou’s death in 1285, the restoration of unified rule in Acre under Henry II of Cyprus and I of Jerusalem did nothing to stem the crisis. No meaningful help came from the west.

121. The fall of Tripoli, 1289.

SIEGES

The military history of the crusades is punctuated by decisive sieges, the commonest form of set-piece large-sale armed encounter in the Middle Ages. In the west they occurred in a landscape of castles; in the eastern Mediterranean in a world of cities. The course of crusades rested on sieges: Nicaea, Antioch, al-Bara, Ma’arrat al-Numan, Arqah, Jerusalem on the First Crusade; Lisbon and Damascus on the Second; Acre on the Third; Zara and Constantinople on the Fourth; Damietta on the Fifth and in 1249; Tunis in 1270. The fate of Outremer was similarly mapped by sieges, both in its establishment and demise: Jerusalem (1099) and the coastal ports from Jaffa (1099) to Tyre (1124) and Ascalon (1153); Jerusalem and Tyre (1187); Acre (1189–91); Beirut (1197); and the systematic Mamluk capture of cities and castles from 1265, including Antioch (1268) and Tripoli (1289), until the conclusive siege of Acre in 1291. Power in the region depended on urban centres and strategic strong-points, possession of which did not rest on rare pitched battles, Hattin excepted. The nature and conduct of sieges differed depending on whether the target was a walled city or a castle, as well as local topographical or architectural circumstances. Cities could rarely be completely sealed by blockade, while castles could more easily be deprived of provisions.

However, three consistent factors determined the outcome of sieges: morale; numbers, especially of besiegers; and the availability or prospect of relief. The Franks’ successes on the First Crusade and in the twelfth century rested on their ability to resist land and sea relieving forces, as did their final victories at Acre in 1191 and Damietta in 1219. Throughout the twelfth century, Frankish sea-power, provided severally by Genoa, Pisa and Venice, played a vital role in effective investment of cities. Even the timbers of derelict ships could supply necessary materials for siege engines, from Jerusalem in 1099 onwards. The collapse of Outremer in 1187–8 and after 1265 was hastened as garrisons of even the strongest castles saw no prospect of relief. Such considerations obviously played directly to the morale of either side. Numerically, garrisons could be modest – a few score or hundreds at most in castles or a few thousand in cities – while besiegers tended to prevail if possessed of enough manpower to withstand inevitably heavy casualties, as with the constant western reinforcements at Acre in 1189–91 or during the later thirteenth century when Mamluk attackers massively outnumbered the besieged Franks: at Acre in 1291, it has been calculated, by 11 to 1.14 Numbers also dictated tactics. The Franks, usually needing to preserve troops even during large crusades, tended to opt for the slower technique of surrounding, harrying and starving opponents into submission, while the Turks and Mamluks, with greater access to additional local forces, adopted more aggressive direct assaults, more able to sustain the ensuing casualties. Successful Frankish sieges tended to last months (Antioch, 1097–8; Tyre, 1124; Damietta, 1217–19) and even years (Acre: 653 days, 1189–91); Turkish and especially Mamluk operations, days and weeks (six weeks at Acre, 1291).

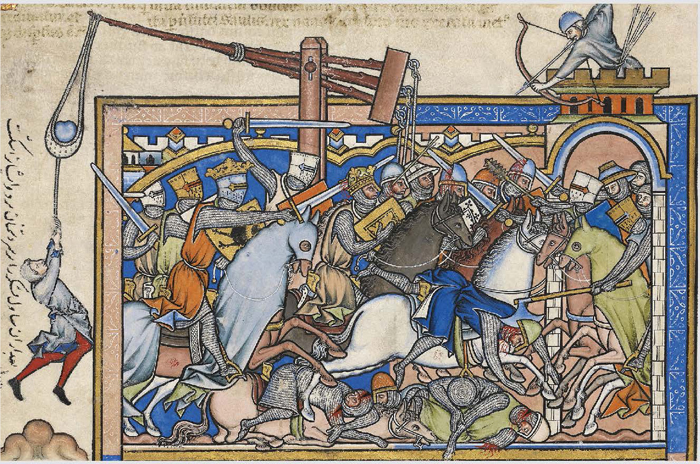

122. Artillery, archery and assault in the thirteenth century.

This was not due to very different siege weapons or tactics. All sides employed ladders; wooden siege towers on wheels or rollers; battering rams; and a range of artillery. Traction- or torsion-propelled throwing machines (mangonels and petraries) and, from the mid-twelfth century, counterweight trebuchet catapults capable of throwing horses or weights over 100kg were used by besiegers and defenders alike.15 They were considered so important that crusaders brought models with them by sea in 1191 and 1202. During their final push to eradicate Outremer in 1265–91, the Mamluks perfected their own massive versions, some, like a number of Frankish ones, prefabricated in transportable sections. Franks, Turks and Mamluks all used sappers, resistance to whom drove many aspects of castle defensive systems, such as elaborate talus (or glacis) structures that also kept siege engines at a distance. All siege warfare was conducted under a mutual hail of arrows and crossbow bolts. However, it appears that only the Franks’ enemies used varying forms of Greek Fire (a preparation of crude oil or naphtha; Byzantine Greek Fire comprised distilled crude oil). However generated, fire proved a very effective weapon in its own right, as gates and many defensive superstructures were wooden as were vulnerable, slow-moving or stationary siege engines. Various mixtures of vinegar were employed to combat flames, with uneven rates of success. However, for all the sophisticated technology, the outcome of sieges depended on the human element on both sides: adequate provisioning for both sides; starvation; disease; hope or prospect of relief; morale; weight of numbers; leadership. Most sieges included efforts to negotiate, not all successful or honest. Depending on the intent of the successful besiegers, defenders were massacred (Antioch in 1098; Jerusalem in 1099; the early Frankish conquests of coastal ports; Antioch in 1268; Acre in 1291); taken into captivity; allowed to leave; or even the civilian elements permitted to remain or return (Tyre in 1124). Castle garrisons most commonly agreed terms. As with any static military confrontation, opponents engaged in various forms of contact, not all violent or hostile.16

The remaining Frankish lordships succumbed piecemeal, some, like Beirut, to temporary Mamluk clientage or shared lordship, others, as at Tripoli, to destruction. The final siege of Acre, prepared by Kalavun in 1290 and completed by his successor al-Ashraf Khalil, lasted from 6 April to 18 May 1291, before the city, pummelled by huge mangonels and overwhelmed by vastly superior numbers, fell amidst incandescent scenes of bravery, mayhem, butchery and despair. The fortified Templar quarter held out for a further ten days before being overrun. Frankish survivors were killed. On the sultan’s orders, the city was ‘razed to the ground’.17 By August, the last Frankish holdings on the mainland – Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, Tortosa and Athlit – had surrendered or been abandoned.

The Failure of Recovery

There was no return. Despite loud ululations, the loss of Outremer re-inforced perceptions of the immense task of reconquest, now discussed in terms of budgets, manpower, training, logistics, intelligence and diplomacy as much as faith and devotion. Pope Nicholas IV (1288–92) authorised another ecclesiastical tenth and, like Gregory X, appealed for advice, some of which proved very detailed, accompanied with illustrative, if not particularly useful maps.18 Any attempt to coordinate a new crusade was wrecked by the fractious politics of the 1290s: the War of the Sicilian Vespers spluttered on; Philip IV of France (1285–1314) fought Edward I of England over Gascony, challenged papal authority over the French Church and failed to resolve tensions with Flanders; Edward I became embroiled in trying to dominate then annex Scotland; Pope Boniface VIII (1294–1303) used a crusade against his Italian rivals, the Colonna. News of the victory of the Mongol Il-Khan Ghazan (1295–1304) over the Mamluks, and his brief re-occupation of Syria (1299–1300) in alliance with Christian Cilician Armenia, provoked illusory optimism.19 Diplomacy continued. The Templars briefly occupied the island of Ruad off Tortosa (1300–3). Prospects for an anti-Mamluk coalition with the Persian Mongols proved a mirage.

Nonetheless, planning, advice and research into the recovery of the Holy Land continued to flourish. A strong literary tide of ‘recovery literature’ only ebbed with the outbreak of the Hundred Years War between France and England in the late 1330s, leaving an increasingly attenuated tradition that persisted for generations. While the possibility of re-occupying the Holy Land had long ceased to be practical, instead it was partly refashioned into a metaphor or allegory for the reform of Christendom.20 The fourteenth century saw only three major attempts to organise a new international crusade to reverse the decision of 1291 – under Clement V (1305–14); by Philip VI of France (1328–50) in the 1330s; and by Peter I of Cyprus (1359–69) during a lull in the Anglo-French wars in the 1360s. Only the last produced military action, an attack on Alexandria in 1365. Sporadic raids on the Levant littoral continued into the early fifteenth century, and Mamluk resources remained a subject of concern for the defenders of Frankish Cyprus and for western merchants. Nevertheless the expansion of Turkish emirates in the Aegean and the subsequent rapid emergence of the Ottoman Turkish Empire in Asia Minor and the Balkans in the second half of the fourteenth century rendered the recovery of the Holy Land a second-order objective even before the Cypriot-Mamluk treaty of 1370 effectively brought the Palestine crusades to an end.

Clement V and Philip IV

Clement V attempted to use the Holy Land crusade as a means to restore the papacy’s position after damaging conflicts during Boniface VIII’s reign had seen a dramatic collapse in Franco-papal relations, which ended with the pope being manhandled by agents of the French king at Anagni in 1303. France, with its substantial resources, direct access to Mediterranean ports and public devotion to the legacy of St Louis (canonised 1297), remained central to any scheme for a major new eastern campaign. With Philip IV of France asserting an increasingly strident quasi-imperial form of royal sovereignty in the Church as well as the State, Clement found he had little room to manoeuvre, especially once Philip demanded papal support as he began to persecute the Templars in 1307. The Templar affair, which dominated Franco-papal relations between 1307 and 1312 (see ‘The End of the Templars’, p. 380), and prompted fresh proposals for the recovery of the Holy Land. French courtiers and hangers-on developed ideas for a French-led crusade that conveniently served extravagant claims of royal supremacy. Shows of papal independence were greeted with threats and bullying. While consistently and possibly sincerely proclaiming his devotion to the cause of the Holy Land, Philip failed to contribute to the independent Hospitaller crusade of 1309. Ostensibly designed to relieve Cilician Armenia and blockade Egypt, in line with current strategic orthodoxy, this planned crusade attracted considerable popular enthusiasm across north-west Europe but, lacking sufficient logistical resources, failed to employ the masses who had taken the cross. The small professional expedition that did embark in 1310 delivered nothing more than completion of the Hospitaller conquest of the Greek island of Rhodes, the Order’s front-line bolt hole to escape the fate of the Templars.

Clement resorted to the familiar precedent of calling a general council of the Church that linked the crusade with wider church reform as well as the immediate crisis of the Templars. Although having to accept the suppression rather than condemnation of the Templars, Philip IV effectively, if temporarily, secured their funds and stood as the main beneficiary of a new crusade sexennial church tithe agreed by the council. The king assumed leadership of the proposed enterprise, in 1313 taking the cross with his three sons, son-in-law, Edward II of England, and large numbers of French nobles and members of the Parisian urban elite. The promise of 1313 soon vanished. In 1314, Philip IV died as did Clement V (leading to a two-year papal interregnum), and Edward II was defeated by the Scots at Bannockburn. The following year saw the start of a catastrophic northern European famine (1315–22). Yet the French court remained committed beyond rhetorical clichés and appropriation of church funds, despite a disruptively rapid succession of monarchs (Louis X, 1314–16; Philip V, 1316–22; Charles IV, 1322–8). Philip V consulted crusade veterans and experts and floated the idea of a lay crusade tax; plans for a relief force to beleaguered Cilician Armenia were briefly entertained by Charles IV in 1323.21 Such activity stimulated a wealth of written commentary, plans, studies and advice on the recovery of the Holy Land, as well as the production and collection of literary and historical crusade-related manuscripts in and around the French court, an interest that sustained fresh plans for a general crusade in the 1330s.22

123. Cilician Armenia, a continental crossroads: Archbishop John of Cilicia in 1287 wearing a robe decorated with a Chinese dragon.

Planning the Recovery of the Holy Land

Advice on recovering the Holy Land fell into several categories, from visions of transforming the world to details of ships’ biscuits, occasionally in the same work. Usually framed by religious, missionary, political or commercial interests, most considered some or all of the means to conduct long-distance military campaigns: geography, routes, strategy, diplomacy, recruitment, training, fund-raising, taxation, wages, weaponry, shipping, logistics, implications for trade, intelligence on the enemy, arrangements for the rule of a reconquered Outremer. While much advice between 1270 and 1340 comprised special-interest lobbying, some was commissioned by popes, such as Gregory X, Nicholas IV or Clement V, or by putative crusade commanders, such as Count Louis of Clermont (c. 1280–1342), a grandson of Louis IX, who asked Marseilles for detailed information on shipping in 1318. Writers included kings (James I of Aragon, Charles II of Sicily, Henry II of Cyprus); Hospitallers (Master Fulk of Villaret and a former prisoner of war in Egypt, the Englishman Roger of Stanegrave); the last Master of the Templars (James of Molay); mendicants with experience of the east (the Franciscans Fidenzio of Padua and Galvano of Levanto; the Dominican William Adam); associates of the French court (Philip IV’s minister William of Nogaret, the Norman lawyer Pierre Dubois, Bishop William de Maire of Angers and the southern French Bishop Durand of Mende); maritime corporations (Marseilles and Venice); merchants (most notably an indefatigable Venetian lobbyist Marino Sanudo Torsello); visionaries (such as Ramon Lull); and an Armenian prince, Hethoum (or Hayton) of Gorigos.23

Beneath the gloss of piety and sectional parti pris certain general features were agreed: Christian peace; united leadership; the destruction of Mamluk power in Egypt; the massive costs, many times royal and papal annual revenues; effective sea power. The need for disciplined professional troops was emphasised, at least for any preliminary campaign (known as a passagium particulare) that most advocated to secure bridgeheads for the mass crusade of conquest (passagium generale). Knowledge of Egyptian and western Asian politics, geography and resources was considered a desideratum. It was to be supported by reference to or – in the case of a Franciscan friar, Fidenzio of Padua, and a Genoese doctor, Galvano of Levanto, in the late thirteenth century, and the Venetian merchant Marino Sanudo in the early fourteenth – the inclusion of maps or detailed navigational charts known as portolans.25 Some writers went into minute detail. Sanudo advised on everything from the prime season for felling timber for ships, to detailed estimated annual naval and military budgets, to precise calculations of crusaders’ daily consumption of biscuits, wine, meat, cheese and beans. While such information had been available from earlier arrangements with troops and shippers, its collation provided an unprecedented resource of information, some of which, notably the level of expense, was distinctly off-putting. The range of advice was impressive, as in Guy of Vigevano’s tract of 1335, Texaurus Regis Franciae, which combined fanciful illustrated war machines with practical advice on maintaining healthy ears, eyes, teeth and diet, and how to avoid poisoning. Guy, physician to Queen Joan of France, dedicated his work to his employer’s husband, Philip VI, then engaged in trying to put some of these plans into action.

THE END OF THE TEMPLARS

The destruction of the Order of the Temple of Solomon, the Templars, between 1307 and 1314 provides one of the most dramatic, notorious and sordid episodes in the civil history of the western European Middle Ages. Despite contemporary slanders and later fantasies, the only sinister aspects in the process against the Templars came from the malignancy of their persecutors and the craven subservience of church authorities. As the fortunes of Outremer careered from dire to hopeless, the reputation of the Military Orders inevitably came under scrutiny. Given their history of rivalry, some argued that the Orders should amalgamate the better to provide moral as well as military leadership against the infidel. The loss of their final bases on the Levant mainland caused the Templars to move headquarters to Cyprus. From there, they continued to harass the Mamluks. With extensive estates and banking interests across Christendom, the Order remained prominent in political establishments throughout Europe, not least in France. The sudden coordinated arrest of all Templars in France by royal officers and confiscation of their property on Friday 13 October 1307 therefore came as a surprise and shock.

The French king, Philip IV (1285–1314), claimed he was acting on behalf of the Church to eradicate gross misconduct and heretical beliefs within the secretive order. Charges levelled by Philip’s aggressive, sanctimonious and mendacious legal team included denial of Christ, spitting on the cross, idol worship, and a range of sanctioned homosexual activities and indecent kissing. In a technique later familiar from twentieth-century show trials, to achieve well-publicised confessions torture was freely applied, including on the Templar leadership. Although accepting the fait accompli of the arrests and ordering the detention of Templars across Christendom, Pope Clement V (1305–14) remained sceptical, suspending the inquiry (February 1308) after the Master of the Temple, James of Molay, revoked his earlier confession in front of cardinals sent to investigate. This provoked a sustained French campaign of political bullying, including more Templar forced confessions, until the pope renewed inquiries (summer 1308), one conducted by papal commissioners and another by local bishops. More confessions were extracted by French bishops in 1309, but where torture was not threatened or used, as mostly in England, Scotland and Ireland, Templars refused to admit to the charges. In 1310, Templar resistance to French persecution grew into organised denial of the accusations and the earlier confessions made under duress. The French government reacted savagely. On 12 May 1310 fifty-four Templars were burnt to death outside Paris after being condemned as relapsed heretics by the archbishop of Sens, a royal stooge; Templar resistance leaders were imprisoned or vanished. Increasingly, the issue became less about Templar guilt than about church authority versus royal power; defence of the former demanded accommodation with the latter, with the Templars paying the price.

At a general council of the Church at Vienne (1311–12), despite widespread opposition, Clement, constrained by the attendance of Philip IV and his army, imposed a pusillanimous compromise. On the grounds that their reputation had been irretrievably damaged, the Templars were not condemned but suppressed (March 1312). Their property was granted to the Order of St John, the Hospitallers (May 1312), from whom, over the next few years the French crown extracted over 300,000 livres tournois in supposed compensation for costs incurred by the arrest and pursuit of the fallen Order. Some Templars were or remained imprisoned; others were despatched to retirement in religious houses; some returned to their families and the minor aristocratic obscurity from which many had come. Finally, in Paris, on 18 March 1314, the four leading Templars still in custody were sentenced by papal judges to perpetual imprisonment. Two, James of Molay and Geoffrey of Charny, protested their innocence and that of their Order. King Philip immediately rushed them to be burnt at the stake on the Ile des Javiaux (now the Quai Henri IV) in the Seine as relapsed heretics.

124. The burning of James of Molay.

125. The destruction of the Templar Order.

Two questions hang over the trial and suppression of the Templars: the truth of the charges and the motives of Philip IV and his ministers. The only sustained evidence of guilt came from confessions extracted under torture or the threat of torture. Despite some modern Roman Catholic apologists and literary hucksters, few give them much credence. The Templars, like other closed institutions, may well have developed idiosyncratic rituals hard to explain to outsiders, but reflecting a homosocial not homosexual environment. As with other religious orders, wealth was no necessary bar to the sincere performance of vocation. Without torture, inquiries failed to uncover coherent evidence of doctrinal unorthodoxy beyond the levels of eccentricity and ignorance common throughout Christian society. Why then the persecution? And why just the Temple? Part of the answer lay in French politics and finance. Since the twelfth century, the Templars had played a central role in the administration of royal finance, providing a tempting target for Philip IV’s cash-strapped but hugely ambitious centralising regime. Whether Philip himself was a useful idiot or evil genius remains contested, but if, as is likely, he played the lead in activating the anti-Templar policy, it is just possible that he sincerely believed in their demonic quality. The attack also played directly into his government’s wider assertion of the French monarchy as a rival if not superior to the papacy as guardian and leader of Christendom, a policy that had led to the attempted abduction of Pope Boniface VIII in 1303, sustained bullying of Clement V, and insistence, at the council of Vienne, on a new crusade with associated taxes under French command.

For the crusades, the consequences of the Templar affair involved the other international Military Orders’ rapid reassertion of their primary military role and relocation of their headquarters: the Hospitallers to Rhodes (1306–10) and the Teutonic Knights to Marienburg in the Baltic (1309). Inevitably there were loose ends. In 1340 a German pilgrim in the Holy Land encountered two ex-Templars, former prisoners of the Mamluks after 1291, living near the Dead Sea. They knew nothing of the grim fate of their colleagues. Persuaded to return to the west, they found themselves welcomed at the papal court.24

126. A plan for a crusade siege tower by Guy of Vigevano.

The crusading legacy of St Louis continued to frame projections of French regality, creating tension between political necessity, public expectation and operational possibility. As the first French king of a new cadet dynasty, Philip VI of Valois (1328–50) embraced the crusade between 1331 and 1336 to bolster his legitimist credentials at home and international standing abroad. He may also have believed it was the right thing to do. Preparations included diplomacy that stretched to the eastern Mediterranean; consulting current and past expert advice; scrutiny of the financial records of Louis IX’s crusades; negotiations with Pope John XXII (1316–34) over money from the Church; and cultivating domestic support through a series of public assemblies at which the crusade was preached. Even knightly salaries were determined. Courtiers and nobles commissioned luxury copies and translations of crusade histories equally as icons of commitment as for scholarly enlightenment.26 In July 1333, Philip was created ‘Rector and Captain-General’ of the crusade by the pope and took the cross the following October. Crucial to Philip’s commitment was the pope’s grant of a new sexennial tithe, the last such general ecclesiastical crusade tax. Much diplomatic wrangling concerned Philip’s access to these funds. While assisting a joint Hospitaller, Byzantine and Venetian naval league against the Turks in the Aegean (1332–4) and considering help to Armenia, Philip appears to have decided on a traditional unitary mass campaign, a so-called passagium generale, without a coordinated preliminary expedition favoured by contemporary strategic orthodoxy. Departure was fixed for 1336.

However, the whole scheme rested on the impractical premise of international peace. Papal hostilities against Italian enemies and suspicions of the German emperor Louis IV after his invasion of Italy in 1328–30 and Spanish indifference were compounded by the deteriorating relations between England, France and Scotland. Edward III of England (1327–77), involved in the French crusade plans from 1332, proved to be the first English monarch since Stephen (1135–54) not to take the cross. Another monarch with something to prove, his bellicose attempts to impose his own candidate as king of Scotland (1332–5) in place of Philip’s ally David Bruce reignited Anglo-French hostility, provoking Philip to link the crusade with agreement over Scotland. This reassertion of traditional rivalries quickly pushed the crusade to the margins of practical politics. The accession of the austere and meticulous Pope Benedict XII (1334–42) further complicated Philip’s schemes, as the new pope was vigilant lest church taxes were diverted away from the crusade. With prospects for an eastern expedition receding and suspicion of French motives and misappropriation of resources growing, Benedict cancelled the crusade in 1336, paradoxically hastening the outbreak of the Anglo-French war he had tried to avoid. The French crusade fleet was diverted to the Channel, and crusade funds misappropriated to pay for French armies, giving the English the excuse to brand Philip’s crusade intentions disingenuous and bogus. Although Philip had encountered delay and difficulty in providing men, materiel and money, his emotional, ideological, political and diplomatic investment in the crusade appears serious. However, the collapse of relations with England destroyed the necessary conditions for such a huge and risky enterprise, a situation rendered near permanent by the subsequent Hundred Years War.31

MAPS

The traditional image of crusaders heading off into the unknown directed only by hope and prayers is wholly untrue. From the beginning, their leaders knew where they were going and how to get there. They knew the world was a sphere and understood a tripartite continental division – Europe, Asia and Africa. The learned knew of the third-century BC Greek Eratosthenes’ nearly accurate calculation of the earth’s circumference of c. 25,000 miles. A thirteenth-century English monk was well aware of the equator where the sun stood exactly overhead twice a year. However, a sense of geography or knowledge of possible routes was not necessarily or primarily derived from or enshrined on maps. Crusaders’ information rested on memory (e.g. of pilgrims or crusade veterans), experience (e.g. of merchants or sailors), and oral testimony and written literary descriptions rather than visual cartography. From the First Crusade onwards, many chroniclers who had travelled on crusade, or recorded the witness of those who did, produced detailed itineraries of land and sea routes and times taken between cities or landfalls. By the time of the Third Crusade there existed a mass of detailed geographical, nautical and topographical information for planners to use. Nautical handbooks, such as the late twelfth-century Pisan On the existence of the coasts and form of our Mediterranean sea or the English De viis maris (Sea Journeys), exploited Arabic and Sicilian geographic texts. It is likely that some of this information was transcribed onto maps and charts, although none survives until a century later.

However, pictorially visualising the world was not conditioned solely by practical utility. Rather, it operated at two levels, representation of the actual physical world initially being overshadowed by virtual, schematic mappae mundi, world maps. These depicted an idealised globe and portrayed images derived from the Bible or popular neo-classical fables, commonly placing Jerusalem at the centre of the world, illustrating religious or imaginative not geographical trigonometry. Mappae mundi were diagrammatic and indicative of an orderly imagined world, not intended as accurate guides to the physical world but rather as illustrations of scripture or history. However, their Jerusalem-centred vision of the world matched the idealism of the crusade. Mirroring chroniclers’ and preachers’ depictions of the cosmic centrality of the Holy City, they suggested the scale of the crusaders’ task and may have been employed in crusade promotion: by the mid-thirteenth century, crusade preachers were being encouraged to acquaint themselves with mappae mundi. By this time, however, written travelogues were being illustrated and supplemented by maps. The English chronicler Matthew Paris produced detailed linear maps of pilgrim routes from England to southern Italy as well as maps of the Holy Land and the city of Acre festooned with text. Increasingly, stylised illustrative maps accompanied pilgrim narratives and crusade advice that proliferated in the later thirteenth century and beyond. In particular, the map accompanying the Dominican Burchard of Mount Sion’s detailed description of the Holy Land (1274–85) inspired a whole cartographical tradition.27

127. The Hereford Mappa Mundi.

128. Pietro Vesconte’s portolan for Marino Sanudo’s crusade advice, 1320s: a chart of the Near East.

These maps were aids, more or less practical, for pilgrimages and religious devotion. More directly functional were the nautical charts that began to be produced in the later thirteenth century in the ports of Italy and the western Mediterranean. Known as portolan charts (from the Italian adjective portolani, ‘to do with ports’), they showed with some precision coastlines, ports, harbours and the distances between, connected with directional gridlines from a number of fixed points. Such charts supplemented the greater knowledge of winds and currents and the use from the twelfth century of compasses, chiefly employed when sun, moon or stars were not visible. Both navigation and forward planning became more informed if not more certain. The habit of creating and consulting maps reflected both practical needs and cultural developments that increased the role of writing and record-keeping, in this case visual, as evinced by the survival of larger numbers of mappae mundi and geographical handbooks from the time of the Third Crusade. However, the earliest explicit evidence for a crusade commander consulting a map, probably a portolan chart, dates from 1270 when Genoese sea captains were reported as showing Louis IX a chart of the port of Cagliari in Sardinia during the king’s stormy passage from Aigues Mortes en route to Tunisia.28

In the specialist advice generated by the decline and fall of Outremer between 1270 and 1330, considerations of the geography of the Levant became central to discussions of military options and logistics. The irruption of the Mongols into Europe and western Asia in the thirteenth century opened new geographical as well as diplomatic horizons, underlining Europe’s inferior size relative to Asia and Africa. By the early fourteenth century, any potential leader of an eastern crusade could be expected to have consulted maps. Some of the earliest portolans were produced between c. 1310 and 1330 by a Genoese cartographer, Pietro Vesconte, working in Venice, many of whose maps were used by the Venetian crusade lobbyist Marino Sanudo Torsello (c. 1270–1343). When he presented his voluminous crusade tract the Liber Secretorum Fidelium Crucis (Book of the Secrets of the Faithful of the Cross) to Pope John XXII (1316–34) in 1321, Sanudo included a portfolio of maps of the world, the eastern Mediterranean and Asia and Palestine, plans of Acre and Jerusalem and five portolans of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Maps became an essential tool in Sanudo’s continuing campaign of persuasion into the 1330s, integral to, occasionally cross-referencing, his written texts, as with his grid-plan map of the Holy Land.29 These charts and maps demonstrated the twin pragmatic and prophetic cartographical traditions so appropriate for the promotion of the crusade. While Vesconte’s portolans represented the most up-to-date nautical charts, the map of Acre harked back to before 1291, and that of Jerusalem mixed modern topography with Biblical site-spotting. The plan of Palestine followed Burchard of Mount Sion’s combination of the Biblical past and physical present, deliberate or not, a metaphor for the crusade phenomenon as a whole.30

129. The siege of Jerusalem, 1099, in a luxury copy of William of Tyre’s Historia commissioned by a member of Philip VI’s court.

Alexandria, 1365, and the End of a Tradition

Realpolitik determined the final stages of the Holy Land wars. By 1343–4, Pope Clement VI (1342–52), who had led Philip VI’s crusade propaganda campaign in the 1330s, was issuing licences to trade with Mamluk Egypt while simultaneously encouraging a campaign against Turkish predators in the Aegean. While lip service was still paid to the needs of the Holy Land in attempts to end the Anglo-French war, only with the long truce following the treaty of Brétigny (1360–9) did prospects for a new eastern expedition revive. The driving force was Peter I of Cyprus. As well as asserting a brand of energetic chivalric kingship, confronting Mamluk Egypt furthered Peter’s attempts to sustain Cypriot commercial interests in the Levant for which the dilapidated Palestinian ports and cities were peripheral. Economics not religion propelled Peter’s occupation of Armenian Gorhigos and Turkish Adalia on the southern coast of Asia Minor in 1360–1. Not a realistic strategic target, recovering the Holy Land nonetheless acted as a recruiting agent during a tour that Peter conducted between 1362 and 1365 across Italy, France, England, Flanders, Poland and Bohemia. At Avignon in March–April 1363, at a conference organised by Pope Urban V (1362–70), King Peter, John II of France (1350–64), Count Amadeus of Savoy, the Master of the Hospitallers and nobles from across western Europe (including an English crusade enthusiast Thomas Beauchamp, earl of Warwick) took the cross, preaching was instituted, indulgences offered, taxes proposed, and a legate appointed – the experienced diplomat Elias of Perigord, Cardinal Talleyrand.

130. Armed galleys, like those of the anti-Turkish naval leagues and the planned passagium particulare.

The momentum of Avignon soon dissipated. John II and Cardinal Talleyrand died in 1364. John’s successor, the cautious, pragmatic Charles V (1364–80), did not share his father’s crusading commitment. However, by June 1365, Peter and the new legate, Pierre de Thomas (d. 1366), supported by papal subsidies, had assembled a polyglot force of perhaps 10,000 at Venice, including hired troops and recruits from France, England, Scotland and Geneva. Although the papal crusade bull had not distinguished between Mamluks and Turks, the Cypriot leadership took the bold decision to attack Alexandria, Egypt’s main and massively defended port. In one of the most spectacular military coups of the age, the city fell by storm to the crusaders on 10 October 1365 after just one day’s fighting. The following week was spent in massacre and pillage. However, the victorious crusaders immediately faced a familiar strategic conundrum of what to do next. Their army lacked the numbers, materiel or cohesion for a serious invasion of the Nile Delta or even, many thought, to defend their conquest. It was later claimed that the Cypriots wished to retain Alexandria as a bargaining tool, ostensibly for the restoration of Jerusalem. More likely, beyond securing enormous booty, they hoped to persuade the Mamluks to accommodate Cypriot trading interests, enhance the position of Famagusta as a Levantine entrepôt while also attracting friendly western European engagement in the region unseen for decades. Whatever the intention, the crusaders evacuated Alexandria on 16 October. Thereafter, the army soon dispersed. The next western European invasion of Egypt was led by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798.

Beyond a glorious and memorialised triumph of western chivalry, and, one distant English observer noted, pushing up the price of spices,32 the sack of Alexandria failed to benefit Cyprus. Cypriot raids on the Levantine coast continued and Peter toured western Europe once more to drum up support in 1367–8, without much effect. More western concern was directed at the growing Ottoman threat, with a new crusading venture led by Amadeus of Savoy to the Dardanelles and the Black Sea in 1366–7. Yet in parallel, from 1366, Peter had begun negotiations with Egypt for a peace treaty. These continued despite his assassination in 1369. Pressure for a deal with Egypt came from Genoa and Venice as well as the Cypriot merchant community, all suffering from the commercial dislocation caused by the 1365 campaign and subsequent Cypriot raids on Levantine ports. Agreement was finally reached with the Mamluk sultanate by Cyprus, Genoa and the Hospitallers of Rhodes and Venice in October 1370. This marked the end of prospects, although not dreams, of the recovery of the Holy Land, three centuries after Gregory VII’s scheme to lead an army to Jerusalem and Urban II’s realisation of it. Regional conflict did not vanish. The remains of the Cilician Armenian kingdom were conquered by the Mamluks in 1374–5; the efforts of the exiled King Leo V (d. 1393) notwithstanding, no retaliation was forthcoming. The Great Schism (1378–1417) intervened. Despite the assertiveness of the 1360s, Cypriot trade, already in decline since the 1340s, was fatally compromised as the Genoese captured Famagusta in 1373 and Italian merchants increasingly traded directly with Syrian and Egyptian ports. A raid on the Syrian coast in 1403 by Jean le Maingre, Marshal Boucicaut, was under the Genoese colours, linked to their continued occupation of Famagusta rather than any lingering hopes for Jerusalem, now accessible to western Christians through organised and regulated pilgrim package tours.33

The recovery of the Holy Land continued to haunt western Christian imagination, attract literary attention and colour diplomatic rhetoric into the sixteenth century.34 Glamorisation of the Holy Land crusades slid as easily into allegory as planning did into wishful thinking. The career and literary trajectory of Peter I of Cyprus’s chancellor Philippe de Mézières (1327–1405) bore striking witness to the process. After joining a crusade led by Humbert Dauphin of Vienne in the Aegean (1345–7), Mézières, a Picard by birth and knight by profession, conceived the idea of a new crusading order, the Order of the Passion, the rules and recruitment for which he refined over thirty years from the 1360s to 1390s. A natural courtier, he played a central role in the organisation of Peter I’s Alexandrian crusade of 1365 and was later associated with the French royal court. However, by the time he composed his chief literary works calling for a new crusade, such as The Dream of the Old Pilgrim (1387) or the Letter to Richard II (1395), he used the crusade more as an emblem and metaphor of Christian morality, faith and unity than a call to arms. Even his later regulations for the Order of the Passion lost touch with reality in their prohibition on initiates fighting anywhere but the Holy Land, despite the advance of the Turks into the Balkans; while his reaction to the Turkish victory at Nicopolis on the Danube in 1396, when a coalition Franco-Hungarian army was crushed by forces under the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid I, relied on arcane allegory, not serious recipes for counter-attack.35 The Jerusalem wars were over.

A MEAL IN PARIS, 6 JANUARY 1378

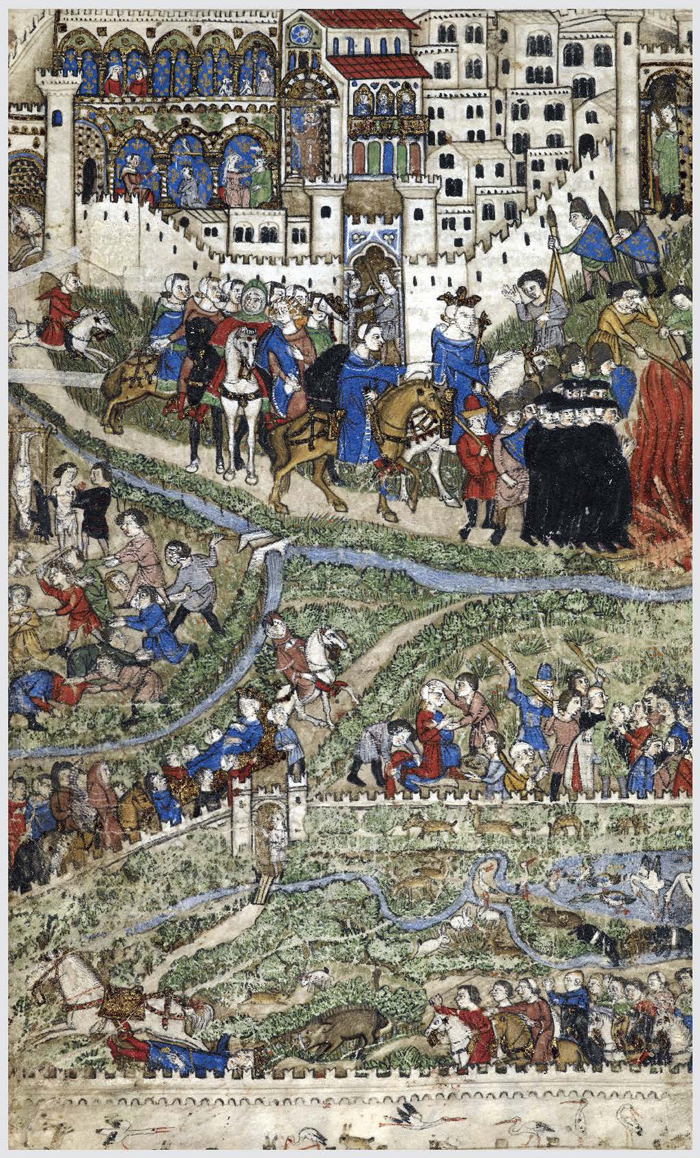

On Wednesday, 6 January 1378, during a state visit to Paris, after visiting Louis IX’s Sainte Chapelle with its relics of the Passion, the Emperor Charles IV of Germany was entertained to dinner by his nephew King Charles IV of France in the great hall of the neighbouring royal palace on the Ile de la Cité. The feast was sumptuous: three courses, each of ten dishes, followed by spiced wine, served to a gathering of five tables of nobles plus a further 800 ‘below the salt’. The emperor, his son and future successor, Wenceslas, and King Charles sat at the high table facing the hall. The diners were presented with a fancifully elaborate theatrical presentation of the siege of Jerusalem in 1099, complete with armed crusaders in a moving ship and a large tiered stage-set of the Holy City defended by soldiers dressed as Turks. Above the defenders perched a figure who ‘in Arabic cried the law’. Led by Godfrey de Bouillon, the crusaders, identified by heraldic flags and surcoats, attacked up ladders, with some falling off, until the city was won. Watching the proceedings from the stern of the pantomime ship was the figure of Peter the Hermit, whose costume, according to the detailed official account of the event, was modelled as closely as possible on chronicle descriptions of him. The lavish production values of this remarkable performance were confirmed by a stunning fine-detailed illumination of the event that accompanied the description in the manuscript text (Bibliothèque Nationale Fr 2813, fol. 473 verso). While unusual in showing a secular, if sanctified, historical scene, the 1378 Jerusalem show was not unique. On 20 June 1389, to celebrate the entry into the city of Charles VI’s queen, Isabelle of Bavaria, Paris staged an outdoor production of a Third Crusade romance, the Pas Saladin.36

The crusades evidently still made good theatre if not good politics. Charles V (1364–80) was the first king of France since Philip I (1060–1108) not to take the cross. However, the idea of and plans for a renewed attempt to retake the Holy Land persisted, if only, by the 1370s, as an idealised cause that might encourage political and ecclesiastical reform in the west and a cessation of the Hundred Years War. Such a policy had been advocated over many years by one of Charles V’s associates, Philippe de Mézières (c. 1327–1405), crusader, former chancellor to the crusading Peter I of Cyprus, and writer of tracts urging moral renewal and a new eastern crusade. He also may have had some experience directing staged performances. The Jerusalem dinner play may have been his idea or staged under his direction. He may even have played the part of Peter the Hermit, strikingly depicted in the manuscript illumination, a role that well suited his later self-image of a poor pilgrim. If so, he subsequently appeared to repent his involvement, writing a decade afterwards criticising the wasteful expense of the lavish feast and lamenting that it had not even served its diplomatic purpose as one of the guests, Wenceslas, had shortly after married off his sister to France’s enemy, Richard II of England.37 Yet, for all that, the Jerusalem show offers tangible evidence of the continued cultural traction of the crusade if only in its dramatic historical resonance, still able to generate recognition, interest and excitement.

131. The play of the siege of Jerusalem, Paris 1378: the figure in the bottom left portraying Peter the Hermit may depict Philippe de Mézières who possibly helped design and direct the performance.