THE OTTOMANS

After 1291, crusading became increasingly regionalised, fragmented, its institutions more bureaucratic, devotion channelled into administrative form and fiscal expediency. Continuing to inform a state of mind, crusading was sustained by habit, liturgy, appeals for alms, taxation, buying indulgences and occasional active service. In a late medieval paradox, there were more crusades, more varied preaching campaigns yet fewer crucesignati. Imaginative association with the Holy Land became formalised. Western Christians’ physical engagement settled on visits by pilgrims, spies, merchants and visiting clergy. Package tours of Jerusalem from the 1330s were officially delegated by the Mamluk authorities to Franciscan friars, who devised suitably moving ceremonies and itineraries, even rerouting the Via Dolorosa for convenience. By contrast with such chaperoned site-seeing, new Islamic powers further west provided fresh, urgent settings for holy war. By the middle of the fourteenth century, the Ottoman sultanate of north-west Asia Minor presented the most serious challenge to Christendom’s integrity since the Mongols in the 1240s. By the sixteenth century, with the Turks battering at the gates of Austria, the survival of Christendom itself appeared at stake, seemingly reduced, in the words of Pope Pius II in 1463, ‘to an angle of the world’.1

The Ottoman Turks

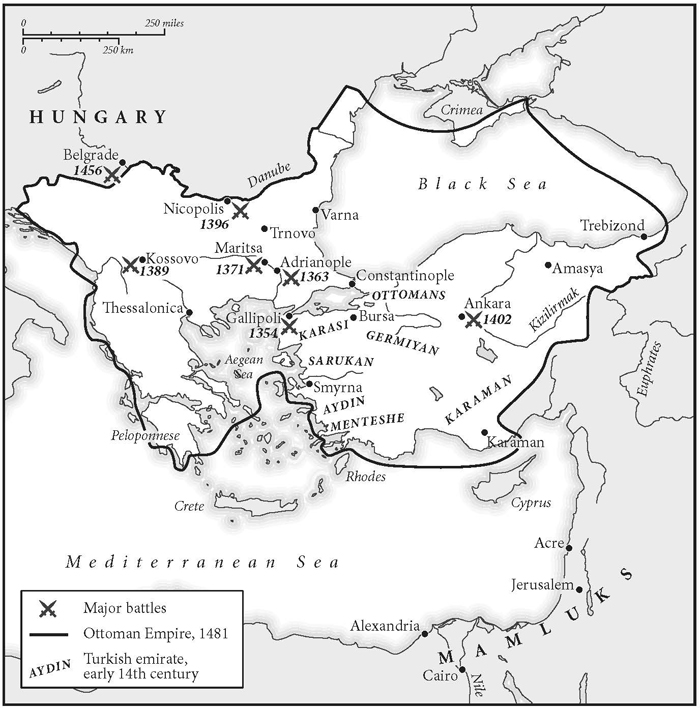

The origins of the Ottoman Empire lay in the fragmentation of political power in the Balkans and Asia Minor during the thirteenth century. From the Danube and Adriatic to the Taurus Mountains, new or attenuated older lordships jostled for survival and expansion. After 1204, the Byzantine Empire had dissolved into successor principalities at Nicaea (then after 1261 Constantinople as capital of an enfeebled restored empire), Epirus and Trebizond; Frankish statelets in Attica, Boeotia and the Peleponnese; Venetian possessions around the coasts and on the islands of the Aegean and Ionian Seas; independent Bulgarian and Serbian kingdoms; and Hungarian penetration south of the Danube into Bosnia and Wallachia. The collapse of the Seljuk sultanate of Rum in the later thirteenth century similarly opened Asia Minor to competitive Turkish emirates sustained by banditry, privateering and service as mercenaries: Aydin, Menteshe and Tekke in western Asia Minor; Karaman in the south-east; and the Ottomans in the north-west, well placed to take particular advantage of political disruption in the neighbouring Byzantine Empire. As well as control of territory and tax revenues, at stake was regional trade, which directly involved Italian powers.

Western attention initially focused on the emirate of Aydin’s piracy operating from the Aegean port of Smyrna (Izmir). The threat to Venetian, Hospitaller and Byzantine interests provoked papally sponsored naval leagues in 1332–4 and 1343–5: Smyrna was occupied (1344–1405) and a crusade mounted by Humbert, Dauphin of Vienne (1345–7), which proved a damp squib. In contrast, by the 1330s, the land-based Ottomans under Osman and his son Orkhan (1326–62) had extended their territory from the region around Bursa to the Sea of Marmora, the Bosporus and Dardanelles. By the 1340s, Orkhan was employed by the Byzantine emperor John VI Cantacuzene (1345–54) against his rivals for the Byzantine imperial throne, giving the Ottomans the opportunity to occupy the Gallipoli peninsula, capturing Gallipoli itself in 1354, the beginning of a European land empire that lasted until the early twentieth century. Subsequent Ottoman progress in Thrace produced contradictory Byzantine responses of alternating alliance and confrontation. Western reactions were complicated by the competing ambitions of Venice and Genoa. While a limited campaign by Count Amadeus VI of Savoy in 1366–7 recaptured Gallipoli and a few Black Sea ports, the Ottoman conquest of the Balkan interior continued from Thrace (Adrianople/Erdine, taken c. 1369, becoming their capital) northwards into Serbia and south into Greece. By the end of the century, the Ottomans had redrawn the political map of the whole region. After overawing the Serbians at the battle of Kossovo in 1389, through conquest, alliance, direct lordship and client rulers, the Ottomans controlled the Balkans from the Danube to the Gulf of Corinth, threatening both Hungary and Constantinople. The Ottoman victory over French crusaders and Hungarians at Nicopolis in 1396 confirmed a new hegemony.

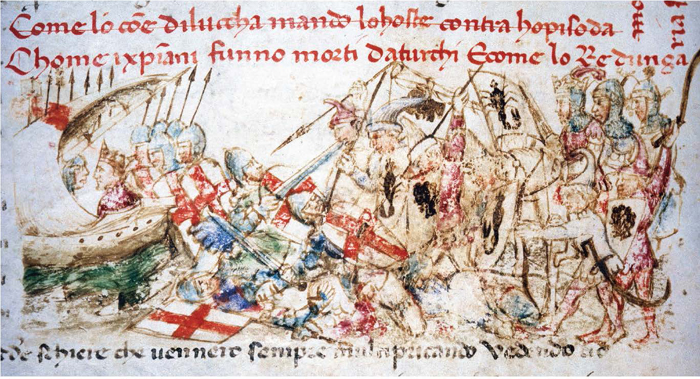

132. Turks defeating Christians, from Sercambi’s Luccan Chronicle, late fourteenth century.

The Ottoman threat to western Christendom dawned only slowly. Most of the early victims were Orthodox not Catholic Christians. The confused politics of Byzantium, Latin Greece and the Orthodox Christian Balkans presented few clear strategies, Urban V’s elision of Mamluks and Turks in promulgating the crusade in 1363 revealing characteristically limited understanding.2 The naval expeditions and costal raids of 1332–67 in Greece and Asia Minor failed to confront the Ottomans’ land-based power or their access to the sea, where they were regularly assisted by the Genoese, eager to seize advantage from the Venetians whose post-1204 maritime empire the Ottomans were dismantling. The idea of a mass land crusade in coalition with local Christians was never fully realised.

No longer dependent on a steppe nomadic economy and culture, the Ottoman polity was settled, confident and accommodating, centred on loyalty to the ruling dynasty and its religion, not on origins, ethnicity or past associations (‘Ottoman’ means follower of the dynasty’s semi-legendary Osman/Uthman). Thus anyone – Turk, Slav or Greek – could become an Ottoman, even, after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, members of the Byzantine imperial family. Although flaunting the ghazi (holy warrior) rhetoric of jihad, Ottoman policy revolved around secular dynastic power not Islamic mission. While Islam provided cohesion for the ruling elite, alliances were rooted in convenience not faith; subjects’ loyalty counted for more than their religion. The parallels between Ottoman and traditional Byzantine policies of accommodation and incorporation of neighbours, rivals and conquered peoples are striking. Communal boundaries were porous. The fifteenth-century Christian Albanian resistance leader George Castrioti (d. 1468) was a Catholic convert who had previously served Sultan Murad II (1421–51) as a Muslim and received a Turkish name, Scanderbeg (Alexander Bey). A future crusader at Nicopolis, the Frenchman Marshal Boucicaut offered to serve Bayezid I (1389–1403).3 The Ottomans began their European conquest as vassals and allies of the Byzantine emperor: rival Greek imperial families married into the Ottoman dynasty (Islamic polygamy proving of great diplomatic use). Christian Serbs fought for the Turks against crusaders at Nicopolis in 1396 and against the Turco-Mongol Timur at Ankara in 1402; Genoese fought with Murad II against crusaders in 1444; Christian allies stormed Constantinople alongside the Turks in 1453. Some Greeks preferred the tax rates of Ottoman rather than Byzantine rulers and even the monks at Mount Athos could argue in favour of the Muslim Turks against the heretical emperor John V Palaeologus (1341–76, 1379–90, 1390–1).4 The view peddled by crusade enthusiasts, despite the evidence of travellers, spies, merchants and diplomats, of uncompromising Muslim enslavement of embittered subject Christian people, ignored reality. Flexible self-interest contradicted rigid idealism as the Ottomans based their new empire in the Orthodox Christian Balkans not Muslim Anatolia.

Regional support for western involvement was patchy at best. The Italian cities were guided by shifting competitive commercial advantage. Defence of the Frankish territories scattered across central Greece and the Peloponnese had never proved popular with western crusaders. The Slav princes, intent on autonomy, were suspicious of foreign interference from Roman Catholic powers, an obstacle magnified in dealings with the Byzantine Empire. Since 1274, the papal price for a crusade to help Byzantium was church union, a euphemism for Greek obedience to Rome, which consistently proved unacceptable to leaders of the Orthodox Church and their lay followers. Increasingly after 1204, the Greek Orthodox Church rather than the emperor provided the focus of Byzantine cultural identity, reinforced by the fourteenth-century Orthodox mystical Hesychast movement. The first reunion agreed at the Second Lyons Council (1274) to suit the diplomacy of Michael VIII Palaeologus (1261–82) against Charles of Anjou was rejected in 1282 by Andronicus II (1282–1328). Facing Ottoman overlordship and later conquest, John V offered reunion in 1355 and travelled to the west in 1369 to secure it, a journey copied by Manuel II (1391–1425) in 1400–1 and John VIII (1425–48) in 1423. Revived Ottoman power after 1420 persuaded elements of the Greek elite to accept church union at the Council of Florence in 1439, a deal that found little support from Greek Orthodox believers. The Union of Florence only served to alienate the Orthodox hierarchy from the last two emperors John VIII and Constantine XI (1448–53) and complicate crusade diplomacy with front-line Orthodox rulers. It was left to Mehmed II the Conqueror (1451–81) to restore the Orthodox patriarchate to Constantinople.

133. Recruiting local Christians for Ottoman service.

In any case, church union did not work; no grand crusade was forthcoming. Steady erosion of territory and revenue, accelerated by civil wars and the consequent presence of expensive foreign mercenaries such as the Ottomans, reduced Byzantium to military, economic and political dependency, hardly more than a client city state under Turkish sufferance or protection. Commercial prosperity, largely sustained by Italians such as the Ottoman-allied Genoese, shielded Byzantine elites while imperial government withered and the emperors faced bankruptcy. For much of the Greek Orthodox and Greek-speaking Mediterranean, the imperial writ was no longer valid. By the 1380s, emperors had become tributaries and vassals of the sultan. In 1346, Sultan Orkhan had married a daughter of John VI; in 1358 one of his sons married a daughter of John VI’s nemesis John V. Manuel II, who cut a bedraggled figure as he traipsed around western Europe in search of aid in 1400–1, had served in the Ottoman army in the 1390s. The complexity and contradictions of Byzantium’s predicament were matched by the inability of western powers to respond. John V’s plan for a crusade in 1355 clashed with major campaigns in the Hundred Years War and papal crusades in Italy. A decade later, the Alexandria crusade diverted energies to the Levant, Amadeus of Savoy’s small crusade in 1366–7 excepted. The resumption of the Hundred Years War (1369) and papal schism (1378) further undermined military resistance to the Ottoman conquests; the western crusade of 1396 only temporarily distracted Bayezid I’s eight-year blockade of Constantinople begun in 1394. The walls of Constantinople proved more effective, at least until the Ottomans employed gunpowder in their siege armoury in the fifteenth century.

Regular papal offers of crusade privileges from the 1360s onwards failed to ignite concerted action in the Mediterranean. Coastal raids and occupation of ports such as Gallipoli and Smyrna provided temporary help for local Frankish rulers, Italian merchants and the Hospitallers of Rhodes, but hardly challenged Ottoman land power. After an Anglo-French truce of 1389, the first revival of active anti-Muslim crusading was directed at furthering Genoese commercial interests. In 1389–90 the French government of Charles VI (1380–1422) agreed to a Genoese plan to seize the Tunisian port of al-Mahdiya following their capture of the island of Jerba off the Tunisian coast in 1388. Supported by indulgences from both Roman and Avignon popes and commanded by Charles VI’s uncle, Louis II, duke of Bourbon (1337–1410), the campaign assumed the character of a chivalric promenade rather than a serious attempt at conquest. Recruits included several English nobles, but numbers remained modest, perhaps 2,000 to 3,000 knights, infantry and archers, carried in forty Genoese galleys and transport ships.5 Lacking the support of church funds or government subsidies, the expedition was necessarily the preserve of wealthy aristocrats, eager to gild martial and social credentials. Although justified with indulgences and eulogised in the language of holy war, there appears to be no firm evidence of anyone taking the cross. Embarking from Genoa in July 1390, the Franco-English army besieged al-Mahdiya for nine disease-afflicted weeks before agreeing to withdraw. The chief consequence was a general re-establishment of long-standing commercial links between Genoa and the Hafsids of Tunis in 1391 followed by similar agreements with Venice (1392) and Pisa (1397). In image a noble crusading endeavour, in practice the Tunis expedition played a minor role in the shifting business relations that had united western Mediterranean trade across religious divisions for centuries. It sat outside the expansionist interventions into north Africa by Castilians and Portuguese backed by papal grants of crusade indulgences and money. Nonetheless, the Tunis expedition provided members of the Franco-English nobility with a chance to flex their sinews as holy warriors. Numerous al-Mahdiya veterans later fought in Prussia or joined the Nicopolis crusade six years later.

134. The Tunis crusade under sail.

The Anglo-French truce of 1389 encouraged more elaborate crusading schemes, stimulated by the Ottoman threat to Hungary following their annexation of Serbia and by a transient mood of sentimental optimism at the English and French courts. Grandiose revivalist ideas incorporating the end of the papal schism, final peace between France and England, and the recovery of the Holy Land were circulated on both sides of the Channel by Philippe de Mézières, now living in Parisian retirement. French and English knights were recruited to Mézières’ New Order of the Passion (Nova religio passionis), which between 1390 and 1395 received the patronage of Charles VI (who went mad in 1392) and Richard II (1377–99).6 The influence of enthusiasts should not be exaggerated. In response to appeals from King Sigismund of Hungary (1387–1437), a plan was prepared in 1392–4 to relieve the Balkans, to be led by Charles VI’s brother, Louis, duke of Orléans, his uncle Philip the Bold, duke of Burgundy, and Richard II’s uncle, John of Gaunt, duke of Lancaster. Money was raised, troops commissioned and negotiations opened with Venice for a campaign expected in 1395. Indulgences were granted by Boniface IX (Rome, 1389–1404) and Benedict XIII (Avignon, 1394–1423), although, as in 1390, no one may have actually taken the cross.7

The scheme soon shrank in scope amid rivalries around the mad king of France, Richard II’s progressive alienation of much of his higher nobility, a Gascon revolt against the English, Anglo-French diplomatic tensions, and difficulties coordinating with the Hungarians. Leadership devolved onto the Burgundians under the duke’s eldest son, John of Nevers: Louis of Orléans opted out and English participation, if any, was meagre. The whole army probably numbered only a few thousand, including a few hundred men-at-arms. Little could be expected from such a modest force. Leaving Burgundy in April 1396, the French travelled overland, reaching Buda, the Hungarian capital, late in July where they combined with Sigismund’s forces. Advancing down the Danube into Bulgaria, taking the frontier fortresses of Vidin and Rahova and massacring the defenders, the army reached Nicopolis (8–10 September) where Bayezid I (1389–1402) confronted them. True to his nickname, ‘Thunderbolt’, Bayezid had rapidly assembled a significant force of Ottoman levies and Serbian allies. His hurried arrival unnerved the French and Hungarians, who were forced into battle on 25 September. As so often in this period, poorly considered battlefield aggression ensured the destruction of French cavalry, while the Hungarians, deserted by their Wallachian and Transylvanian allies, fared no better. The Christian army was destroyed. French casualties were heavy, the captured, including John of Nevers, later ransomed for huge sums.

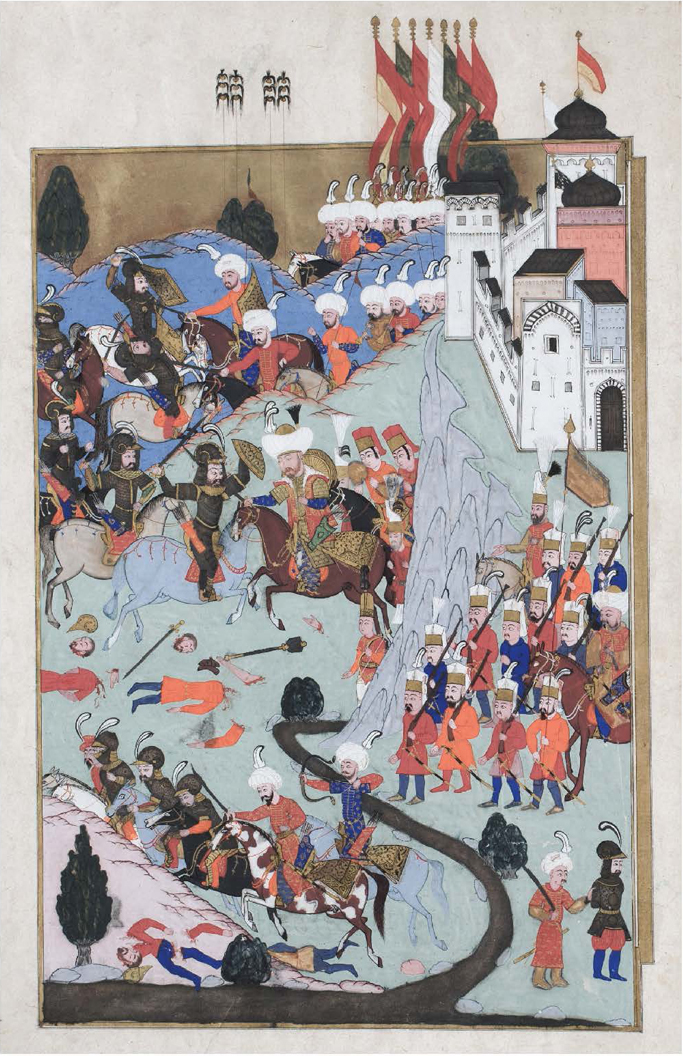

135. Bayezid I routs the infidels at Nicopolis.

The Defence of Christendom

The disaster at Nicopolis confirmed Ottoman power in the central Balkans while exposing the inadequacy of traditional crusade strategies and the problems of coordinating the defence of eastern Europe. Resistance to Ottoman advance now lay firmly with the frontier kingdoms of central and eastern Europe and Venice, supported by papal grants of indulgences and money with occasional recruitment of western troops. Urgency was deferred as Bayezid failed to capitalise on Nicopolis with further conquests along the Danube or by capturing Constantinople. After 1400, his priority to control Turkish emirates in Anatolia drew him into conflict with Timur the Lame (1336–1405) when the Turco-Mongol steppe ruler, whose Asiatic empire stretched from Mongolia to northern India and Persia, turned his attention to western Asia. In 1402, Timur defeated and captured Bayezid at the battle of Ankara, provoking two decades of Ottoman civil war and disintegration of their control over territories both in Europe and Asia Minor. Domestic political crises prevented western powers taking advantage: instability in Germany following the deposition of Sigismund’s brother Emperor Wenceslas in 1400; civil wars in France, over control of the mad king Charles VI, and in England in the aftermath of the deposition of Richard II (1399); continued efforts to end the papal schism, only finally achieved by the Council of Constance (1414–18) in 1417; the renewal of the Hundred Years War by Henry V of England in 1415; and the revolt of the Czech Hussites in Sigismund’s kingdom of Bohemia and the subsequent launch of crusades in 1420. The Anglo-French peace treaty of Troyes (1420) was accompanied by predictable talk of uniting to confront the infidel. A Flemish traveller, knight and diplomat, Ghillebert of Lannoy was sent east as a spy. However, Henry V’s death (1422), the long minority of Henry VI, the continuation of the French wars, and the concentration by Sigismund, now emperor, on the Hussites diverted attention away from eastern Europe where, under Mehmed I (1413–21) and Murad II (1421–51), Turkish rule was restored over much of the central Balkans. By the late 1430s, most of Serbia was again annexed, the Danube provinces of Hungary and Wallachia threatened, and a new siege of Constantinople begun (1442). While fourteenth-century Ottoman rule had relied on delegated authority to Turkish governors, regional allies or clients, after the re-imposition of authority the empire became more highly centralised. Reassertion of control over the sub-Danubean Balkans took just a generation as the Ottomans began to employ cannon and naval power, with local responses conditioned by self-interest not holy war. The subsequent increase in Ottoman raids across the Danube and the prospect of Constantinople’s fall invited a new international effort.

The Crusade of Varna, 1444

Pope Eugenius IV (1431–7) took a serious interest in the eastern question. He secured advice from veterans, merchants and self-styled experts, some of whom identified the Ottomans as the chief threat. The nominal union with the Orthodox Church at the Council of Florence (1439) was followed by making two Greek clerics with knowledge of the Turks cardinals. In 1442–3 indulgences were issued, a fleet planned and a legate, Julian Caesarini (previously a legate on the anti-Hussite crusade of 1431), appointed to eastern Europe. Eugenius hoped to capitalise on the effective resistance to the Ottoman advance by John Hunyadi, voivode of Transylvania (1441–56; regent of Hungary, 1445–56). Although the new king of Hungary, Wladislav III of Poland (king of Poland, 1434–44; Hungary, 1440–4), had recent diplomatic accords with the sultan, he agreed the scheme. A coalition was assembled. The Venetians were to blockade the Dardanelles to prevent Ottoman reinforcements by sea, while Hunyadi led a Hungarian and Serbian army into Bulgaria. Initial coordination failed. Neither the Venetians nor a western fleet were on station when the first land attack began in the autumn of 1443. The operation was hampered by conflicting allied objectives. The Hungarians sought security of their frontiers; the Serbs the recovery of their independence. Neither supported Caesarini’s ambition to relieve Constantinople as they saw there was no Byzantine Empire left to revive, with much of the immediate European hinterland of Constantinople already substantially Turcified. Murad II had played on the allies’ divided expectations by offering peace terms, which George Brancovic of Serbia (1427–56) accepted while Wladislav of Hungary declined. These negotiations delayed the muster of the Christian army, allowing the Ottomans time to assemble their defence.

Hunyadi’s initial campaign in 1443–4 with a large Serbo-Hungarian army, with recruits from Bohemia, Moldavia and a few from the west, had been a success. Attacking through Bulgaria, Nish and Sofia were captured and Erdine (Adrianople), the Ottoman capital, menaced, before Hunyadi withdrew to Belgrade. Plans for 1444 called for the land army to link up with an allied fleet on the Black Sea coast of Bulgaria. However, when the Venetian flotilla of twenty-two or twenty-four galleys, paid for by the papacy, Burgundy and Venice, finally appeared in the Dardanelles in July 1444, it did not move into the Bosporus and Black Sea as planned, failing to intercept a large Ottoman army crossing to Europe north of Constantinople in October 1444. Fear of losses and provoking the Turks induced paralysis in the Venetian naval commander. The allied army under Hunyadi and King Wladislav was abandoned to face the much superior Ottoman force at the Bulgarian port of Varna. The battle on 10 November lasted all day. Casualties on both sides were enormous. King Wladislav and Cardinal Caesarini were killed, sapping morale and persuading Hunyadi’s Hungarians to withdraw.

The Ottoman victory further consolidated their rule over Rumelia (their Balkan provinces) while highlighting their enemies’ divisions. Varna’s slaughter confirmed the scepticism of many Serbs, Hungarians, Moldavians, Poles and Venetians at the wisdom of aggressive policies towards Ottoman power favoured by western strategists. There were exceptions. Hunyadi, now regent of Hungary (for Ladislas V, 1444–56), persisted in challenging the Turks across the Danube frontier, in 1448 obtaining crusade indulgences from Nicholas V (1447–55) for a campaign into Serbia where he was defeated by Murad II at Kossovo, the site of the battle of 1389. The 1448 bull fitted a familiar fifteenth-century papal stand-by, issuing crusade credentials as a means of focusing diplomacy, asserting papal authority and, through the sale of indulgences and church taxation, supporting front-line commanders with financial assistance. Only in the 1450s and early 1460s did this pattern stretch to attempts to organise substantial crusading in western Europe in response to the fall of Constantinople (1453) and the defence of Belgrade (1456).

The Fall of Constantinople 1453: Another Crusade that Never Was

Constantinople fell to the Turkish armies of Mehmed II (1451–81) on 29 May 1453 after a fifty-three-day siege. The last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, was killed during the final assault. Bankrupt, diplomatically isolated, heavily outnumbered, reliant on Italian mercenaries, the defenders of Constantinople, reduced to a beleaguered city state, had been left to face the Turkish heavy artillery and massed infantry without allies. News of the city’s fall and subsequent sack and massacre provoked the most concerted international efforts by the major western powers to gather a grand crusade of the fifteenth century. Horror stories of the slaughter, enslavement and ransoming of Greek civilians excited polemic narratives of barbarism overthrowing civilisation (‘a second death of Homer and Plato’ in the words of the humanist Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, the future Pope Pius II)8 to complement familiar ritualised hysteria and the traditional trope of Christendom in danger. The crisis deepened as the Ottomans consolidated their hold over Serbia (1454–5), threatening Hungary and the middle Danube, and conquered the remaining Frankish and Greek territories on mainland Greece: Athens fell in 1456; the Peloponnese between 1458 and 1460; Venetian Euboea (Negroponte) in 1470. Central Europe, the remaining Venetian holdings in the Aegean and Ionian Seas and the Hospitallers on Rhodes all appeared vulnerable.

Once again, western reaction hardly addressed reality. Byzantium had long been a failed state, its demise the consequence of regional forces not western hostility or indifference. Ottoman rule did not plunge the region into barbaric tyranny, many in the Balkans finding satisfactory degrees of accommodation with the new rulers. The Ottomans avoided systemic religious persecution while providing harsh security and reviving the regional economy, with Constantinople once more the centre of an eastern Mediterranean commercial as well as political empire. European neighbours, trading partners and regional clients adopted pragmatic strategies at odds with the crusade revivalism generated at the papal curia and among sympathetic rulers such as the dukes of Burgundy.9

Nevertheless, from Germany to Spain, a new crusade was aired. Pope Nicholas V (1447–55) issued a crusade bull, Etsi ecclesia Christi (30 September 1453). War with the Turks was considered by the German imperial Reichstag in 1454–5, with Duke Philip of Burgundy (1419–67) present at Regensburg in April 1454. New techniques of publicity and propaganda were employed. Pamphlets circulated widely, exploiting the very recent invention of printing. Nicholas V’s successor, Calixtus III (1455–8), authorised preaching, church taxes and the sale of indulgences, built galleys in a short-lived arsenal on the Tiber, and sent a fleet to the Aegean in 1456–7. This recovered Lemnos, Samothrace and Thasos and defeated a Turkish fleet at Mytilene before raiding the Levant towards Egypt. Calixtus established a separate curial department for proceeds of indulgence sales and clerical taxes, the camera sanctae cruciatae. While clergy complained about taxation, the indulgence campaign went well. Printed forms of sale were introduced. To give a lead, Calixtus sold papal assets including plate and valuable bindings from the Vatican Library founded by Nicholas V. Calixtus’s former employer King Alfonso V of Aragon (1416–58; also king of Naples, 1442–58) took the cross as did the German emperor Frederick III (1440–93), whose Habsburg family lands bordered Hungary. Although Philip of Burgundy did not take the cross, Burgundian commitment was glamorously displayed at Lille in February 1454 during the lavish and gaudy Feast of the Pheasant at which 200 nobles swore to fight the infidel.

136. Epistolae et orationes: Bessarion’s pamphlet on the Turkish war, printed 1471.

Fantasy was not confined to festive theatricals. Duke Philip’s proposal for a campaign in 1455 ignored modest German enthusiasm, the opposition of Charles VII of France (1422–61) and, crucially, Venice’s treaty with the Ottomans in 1454. The death of Nicholas V (April 1455) further postponed action. Apart from taxing his subjects, Duke Philip hardly moved to organise military or naval operations, perhaps surprisingly given his previous sustained patronage of crusading projects and his contributions to fleets to help Rhodes (1429, 1441, 1444) and Constantinople (1444–5). International diplomacy failed to coordinate western policy or investment despite Cardinal John Carvajal’s crusade legation to Hungary (1455–61) during which he oversaw preaching and cross-giving. Alfonso V’s proposal for a massive amphibious attack in 1457 seemed to owe more to a desire to burnish moral credentials than serious policy. Much rhetoric still harked back to historic Holy Land wars of the cross. Deep-seated conflicts of interest and divisions between the western powers prevented any muster of a large international army. Despite significant numbers taking the cross and many more buying indulgences, the limits of practical crusading were further exposed. Thereafter, crusading institutions primarily supplied moral status, public support, finance for modest naval expeditions, and occasional aid for local front-line resistance to the Turks.

Belgrade 1456

The urgency of the Ottoman threat contrasted with the costive responses of western rulers. The ubiquitous use of crusade bulls and preaching chiefly to raise taxes or sell indulgences undermined public confidence, not in the cause or the efficacy of the spiritual rewards so much as in prospects for action. Pope Pius II wryly observed of crusade preaching a few years later: ‘People think our sole object is to amass gold. No one believes what we say. Like insolvent tradesmen we are without credit.’10 Yet preaching and marketing indulgences sustained popular awareness, even alarm, which could translate into active engagement, as shown in events surrounding the defence of Belgrade. In the summer of 1456, Mehmed II advanced up the Danube. The siege began in early July, Mehmed assuming an easy victory as the small garrison was prepared to agree terms. However, the city was unexpectedly reinforced by a substantial army assembled and led by John of Capistrano, a septuagenarian Observant Franciscan enthusiast for crusading and moral renewal.

A prominent figure in an Order that held a tradition of preaching against Jews and other perceived enemies of the Church, John’s mission had begun in 1454 as he made a round of visits to Burgundy and to the imperial diet. Whilst trying to interest Regent Hunyadi of Hungary in a fanciful scheme for an army of 100,000 crusaders, John toured Hungary between May 1455 and June 1456, a figure of conspicuous sanctity, austerity and honesty which he combined with shrewd organisational skills. His carefully orchestrated progress was unhurried – 375 miles in fourteen months, less than a mile a day – culminating in a grand ceremony at Buda in February 1456 where he received the cross from the papal legate, John of Carvajal. While Hunyadi enlisted the nobility, John, his team of preachers and local bishops recruited non-nobles, exploiting the Hungarian system of military levies known as the militia portalis that provided a ready supply of armed peasants.11 From beyond Hungary, John signed up followers from Austria and Germany including Viennese students, many attracted by his appeal for people not just money. While John’s carefully crafted aura of sanctity later encouraged an exaggerated retrospective hagiography, alongside mundane secular organisation his preaching and charismatic leadership clearly helped inspire a crusader army of many thousands whose numbers and morale played a significant part in relieving Belgrade. Mehmed’s calculation on the modest size of the Belgrade garrison and the repeated preference of Hungarian nobles for accommodation was upset by the appearance of John’s crusaders after 2 July. They altered the military balance, helping Hunyadi break the Turkish naval blockade (14 July) and the defenders repel the main Turkish attack on the night of 21–22 July. On 23 July they led the destructive counter-attack on the Turkish positions as Mehmed prepared to withdraw, his expectations of a quick victory decisively dashed.

137. Moravian fresco of 1468 showing the siege of Belgrade.

The image of simple peasant faith triumphing where noble professionalism had failed proved irresistible. Not only conforming to well-worn polemic tradition, it also reflected the potency of peasant armies in late medieval and early modern Europe mobilised for political or ideological causes and grievances, as seen from the Shepherds’ Crusades of 1251 and 1320 to the Hungarian peasant crusaders’ anti-noble insurrection of 1514 and the German Peasants’ War of 1524–5. The element of social challenge was displayed at Belgrade when John’s crusaders and Hunyadi’s nobles and professionals briefly fell out over the division of booty and chain of command. The crusaders at Belgrade appeared to embody a rhetorical model of practical virtue: temporal success through the highest spiritual standards, with John’s personal charisma and revivalist message providing a dynamic unifying force. Yet, as with other populist movements, John of Capistrano’s crusade proved evanescent, no more than a summer’s dramatic promenade. He disbanded his army immediately its objective had been achieved in late July 1456 and died of the plague in October. While the crusaders had saved Belgrade and the central Danube, it was left to local garrisons, truces and practical accommodations to maintain the integrity of the Hungarian frontier against the Ottomans until the 1520s. Despite constant diplomatic talk, there were no further significant Danubian crusades; the Ottomans continued to consolidate their power from the Black Sea and Serbia to Cilicia. The Belgrade victory receded into poetic and pious commemoration: in 1457, Calixtus III instituted general observance of the Feast of the Transfiguration to be held on 6 August in honour of the day the previous year that news of the Belgrade victory had reached Rome. In England a poetic romance, Capystranus, found its way into print half a century later.

The Crusade of Pius II

When Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini (1405–64), prominent humanist scholar, diplomat and late convert to the priesthood, was elected Pope Pius II in 1458, he immediately revived calls for a crusade, a cause he had been advocating for two decades. Closely involved in crusade diplomacy since 1453, he summoned a council at Mantua (summer 1459–January 1460) to discuss it. Pius pressed ahead despite lukewarm international response and deteriorating international prospects: civil war in England; French opposition to what they regarded as Burgundian crusade posturing; and papal involvement in a protracted succession contest in Naples that pitted the French against the Aragonese. Pius’s old-fashioned rhetoric suggested a traditional mass crusade not just to defeat the Ottoman Turks but also recover Jerusalem. This struck some as impractical but also thin cover for an attempt to assert papal authority. Little came from Mantua. Trapped by his cosmic rhetoric and lurid demonisation of the Turks, early in 1462, Pius decided to lead the crusade himself, perhaps the only way to convince a sceptical international community. The preaching campaign relied on conservative rituals of encouragement, the liturgy of taking the cross minutely choreographed down to the placing (on the breast), colour (red), and material (silk or cloth) of the crosses to be sewn onto the clothes of crucesignati.12 Yet, prematurely aged, already an invalid, Pius hardly generated confidence, his gesture appearing more sacrificial than practical, an act of martyrdom not leadership. However, when he renewed the crusade appeal in October 1463, support seemed available from Burgundy and Venice. A fresh plan advocated a smaller, more realistic expedition against the Turks in the western Balkans. Preaching, cross-giving, Holy Land indulgences, privileges and financial arrangements were announced. While trying to attract other Italian states to his scheme, Pius forged a new coalition between Burgundy, Hungary and Venice. Ancona was set for the campaign’s muster. A Venetian fleet would convey the crusaders across the Adriatic to combine with the Hungarians or the Albanian resistance leader Scanderbeg.

On 22 October 1463, Pius formally declared war on Mehmed II. The response was mixed. Despite another lavish crusade fête at Christmas 1463, Philip of Burgundy only despatched 3,000 men under his bastard Anthony in May 1464. While a few other small bands from north of the Alps and Italy moved towards Ancona, only one cardinal provided a galley, Rodrigo Borgia, nephew and protégé of the crusade enthusiast Calixtus III, later notorious as Pope Alexander VI.13 Pius also provided galleys and, in St Peter’s on 18 June 1464, took the cross, possibly the only pope in office to do so to fight the infidel rather than political enemies in Italy. However, when he set out for Ancona in late June, he was already seriously ill. The Venetian fleet commanded by Doge Cristoforo Moro was delayed. Soldiers in the papal army at Ancona began to desert: the curtains of Pius’s litter were said to have been drawn shut to stop the now dying pope see them go. He died on 14 August. His crusade died with him. Pius’s heroic, pathetic pursuit of a grand crusade definitively underlined the difficulty if not futility of such designs, a lesson not lost on his successors. His most tangible contribution to the crusade lay elsewhere, in initiating the process of reserving to the papal crusade treasury the monopoly profits from alum (used to fix dyes in textiles) discovered at Tolfa in the Papal States in 1461.14

From Crusade to Realpolitik

Pius II’s crusade scheme had recognised one element of the new political reality. The immediate frontier with the Turks lay along the Danube and down the Adriatic. Regions such as Croatia became war zones. By 1478, a decade after Scanderbeg’s death, Albania had been absorbed into the Ottoman Empire. In 1480–1 the Turks briefly occupied Otranto on the south-east tip of Italy, a shocking incursion into the heart of western Christendom that provoked another round of hand-wringing, crusade bulls and fund-raising. In the Aegean, the Hospitallers only narrowly survived a long Turkish siege of Rhodes in 1480. The death of Mehmed II in 1481 and an Ottoman succession dispute under Bayezid II (1481–1512) lessened the immediate pressure in the Adriatic: Bayezid even struck a deal in 1495 with western powers to keep his rival claimant, Djem, captive. However, Venice lost its remaining mainland holdings in Greece between 1499 and 1502, including the Adriatic port of Durazzo, while the Ottomans continued to harden their control over Rumelia and completed their annexation of the Black Sea and lower Danube.

138. Crusade economics: alum mines at Tolfa.

Pius’s successors reverted to pragmatism: selling indulgences to fund front-line rulers, and building anti-Ottoman alliances, which in the 1470s included Uzun Hassan, a Turcoman warlord in Azerbaijan, and approaches to the Tartars of the Golden Horde north of the Black Sea, as well as front-line rulers such as Stephen III of Moldavia (1457–1504). Awkwardly, the heretical Hussite ruler of Bohemia, George Podiebrad (1458–71), promoted his own scheme for a new international crusade in 1463 but instead faced a crusade against him in 1466–7. Crusade credentials helped secure a royal title for Hunyadi’s son Matthew Corvinus as king of Hungary (1458–90). The Poles and Hungarians sought rival patriotic solidarity and international advantage by promoting their kingdoms as bastions (antemurales) of Christendom against the infidel. However, political disunity in the west and on the Balkan frontier undermined attempts to gather effective coalitions to combat the Turks. For those on the front line, such as the Moldavians, advantage and survival not ideology determined policy. Innocent VIII’s crusade council of Rome in 1490 proved abortive and Alexander VI’s crusade proclamation of 1500 was largely ignored.

139. Turks preparing to attack Rhodes, 1480, from William of Caoursin’s account, 1483.

17. The Ottoman advance in Asia Minor and the Balkans.

The draining Italian wars (1494–1559) pitted Italian states and the major powers of continental Europe against each other, further compromising crusade diplomatic solidarity and political will. Combatants, such as Genoa, Florence, Milan and Naples, felt no compunction in allying against Venice or with the Ottomans. In 1500 the Polish king Jan Olbracht (1491–1501) voiced widely shared suspicions that Venice itself habitually sought to shirk its responsibility by ‘searching for ways to transfer the war from their lands to ours, if they can’.15 The Venetian-Turkish treaty of 1503 effectively acknowledged the Ottomans as legitimate political partners and rivals. The efforts of Leo X at the Fifth Lateran Council (1512–17), the issue of a crusade bull (1513), church taxation and indulgences (1517) generated some short-lived diplomatic momentum, expressed in the general European pacification agreed at the treaty of London (1518), and the despatch of two French flotillas to the east in 1518 and 1520. However, the Lutheran schism, the renewal of the Italian wars, and the persistent armed rivalry of Francis I of France (1515–47) and Charles V (1500–58) of Spain (1516–56), Naples (1516–54) and Germany (1519–58) prohibited any concerted response to the new surge in Ottoman aggression under Selim the Grim (1512–20) and Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–66).

140. Suleiman the Magnificent at the battle of Mohacs, 1526.

Sultan Selim’s conquest of Syria, Palestine and Egypt (1516–17) created an eastern Mediterranean territorial empire not seen since seventh-century Byzantium, stretching from the Danube to the Sahara, although the rise of the Shi’ite Safavid Empire based in Iran and Iraq prevented the reunification of the Fertile Crescent while offering western powers a potential new ally. Selim’s conquests made the whole Mediterranean basin a war zone between Ottomans, their allied privateers and pirates, and the Venetians, Hospitallers and Habsburgs under Charles V. Over the next two centuries, the Habsburg–-Ottoman contest played out from Tunisia to Austria, punctuated by wars and truces. In central Europe, Belgrade fell to the newly emboldened and resourced Ottomans in 1521, most of Hungary after the crushing Turkish victory at Mohacs in 1526. Vienna was unsuccessfully besieged by the Turks in 1529 and Austria attacked again in 1532, with the seat of action settling across the middle Danube. At sea, the main theatres of confrontation included the Aegean, Adriatic and the narrows between Sicily and Tunisia. Rhodes fell in 1522, the Hospitallers being relocated further west on Malta in 1530. The Ottoman victory over a papal-Habsburg-Venetian fleet off Prevesa in Epirus in 1538 gave supremacy in the eastern Mediterranean until their heavy defeat at Lepanto in 1571, a setback balanced by their conquest of Cyprus the same year. Charles V did succeed in capturing Tunis in 1535, which was held until 1574, and Malta successfully resisted a sustained Ottoman siege in 1565.

141. The battle of Lepanto.

Such shifting intercontinental engagement encouraged dialogue, exchange, even alliance, as well as hostility. With both sides grappling with the problems of managing large fissiparous empires, Ottoman-Habsburg truces were agreed in 1533 and 1545. Iberian crusading energy was increasingly focused on the western Mediterranean, north Africa and the east Atlantic. A defining moment came in 1536 when Francis I allied with Suleiman I against Charles V, the first of a series of such treaties. In 1542–4, naval cooperation saw a Turkish fleet joining the French in besieging Habsburg-held Nice and being allowed to use Toulon as a base. In such circumstances, Pope Paul III’s hope in 1544 that the Council of Trent he was summoning would initiate a new anti-infidel crusade showed the tenacity of the ideal allied to a level of wishful thinking that lacked credibility even in Catholic circles.16 Growing economic stability and prosperity in the Ottoman Empire stimulated local, regional and international commerce regardless of faith, politics or persistent formal papal trade embargos. Venice secured an Ottoman truce in 1573 that stuck for seventy years; Spain, since 1556 separate from the empire, followed suit in 1580. In central Europe a recrudescence of war between 1593 and 1606 ignited embers of crusade enthusiasm in the west, for example in France, as did the Ottoman conquest of Crete (1669) and the central European Holy League from 1683 to 1699. However, in Habsburg lands the crusade remained chiefly a device to raise money.

142. A new dispensation: the siege of Nice by a Franco-Turkish alliance, 1543.

Elsewhere, by the mid-seventeenth century the Ottomans, while still demonised as decadent violent tyrants, were regarded in terms chiefly of power, territory and trade, formalised in the English and French Levant companies. The Turkish policy of Louis XIV of France (1643–1715) in the 1660s briefly encouraged ideas of holy war before subsequently emphasising commercial cooperation and political advantage.17 Bulls continued to be issued. The cross could still be taken by individuals for personal penance and salvation. Association with the naval power of the Hospitallers on Malta always possessed a religious dimension, seen by some in terms of wider Roman Catholic revivalism. War in defence of the faith still appealed across the new confessional divides. Despite generations of alliance, French troops helped defeat the Ottomans at Saint Gotthard in 1664. Traditional rhetoric could strike chords across Europe’s nobilities, attracting recruits to defend Crete in the 1660s. However, as the seventeenth century drew to a close and attitudes towards the Turks slid from fear to contempt as the Ottoman military threat diminished, crusade institutions and idealism as tools in anti-Ottoman politics ceased to be relevant and slipped into complete disuse.