NEW CHALLENGES AND THE END OF CRUSADING

The Italian Wars (1494–1559), conquests in the New World (after 1492), the opening of a sea route to the Indian Ocean and southern Asia (from 1487) and the Protestant upheaval (from 1517) reshaped European culture, attitudes and politics. In an increasingly diverse religious universe, the crusade retained a place, for some still addressing urgent issues of conviction, salvation and identity. The Old and New Worlds could meet. Charles V paid for his capture of Tunis in 1535 with conventional church taxes and sale of indulgences (authorised by a papal bula de crozada) but also with loot from South America. For many Roman Catholics, the Protestant schism of the sixteenth century presented as serious a challenge to their concept of the right order of the world as did the Ottoman advance. Reformists rejected the crusade’s ideological basis in papal authority and the late medieval penitential system epitomised by the sale of indulgences, seen as materially corrupt and theologically wrong. Yet a sense of Christian solidarity in the need to combat the infidel Turk was shared. Protestant London celebrated the crusading victory at Lepanto in 1571; Luther condoned war to repulse the Ottoman. Yet, while its rhetoric thrived, not least at the papal curia, active crusading faded. The emotions and policies once the crusade’s preserve found expression elsewhere.

This slow transformation was hardly predestined. In 1400 crusades featured prominently in the armoury of western Christendom across a wide range of conflicts. Crusading raised money and framed diplomacy, in tune with popular enthusiasm and elite chivalric self-image. The reign of Pope Eugenius IV (1431–47) indicated crusading’s vibrancy. The Council of Florence in 1439 secured the nominal union of the Latin and Greek Churches. The pope received treatises and pamphlets on the Ottomans and the recovery of the Holy Land. He welcomed representatives from the Coptic Churches of Palestine, Egypt and Ethiopia, and made approaches to minority Christian communities in Armenia, Iraq and Cyprus. Two Greeks with knowledge of the Turks were created cardinals, Isidore of Kiev and John Bessarion. Eugenius took an active role in the anti-Turkish crusade in 1439 and 1444, and issued crusade bulls for Castilian attacks on Granada and Portuguese attacks on Tangiers in 1437 and 1443.1 Dealing separately with Portuguese aggression along the coast of west Africa and in the islands of the western Atlantic, in 1436 he reversed an initial ban on force to coerce pagan natives (1434) after pressure from King Duarte of Portugal (1433–8), a volte face allowing for the subjugation of pagan natives before conversion, a precedent later employed to devastating effect in the Americas. While invasions of north Africa were treated as extensions of the Iberian Reconquista, Atlantic pagans lived in regions that had never been part of Christendom and so did not easily fit canon law categories as legitimate targets for religious violence.2 Although in the Maghreb and the Atlantic the crusade and papal licences were subordinate to royal policy, they still demonstrated a role for the pope’s leadership after the challenges of the Great Schism, the rival claims to ecclesiastical authority by the representative church Council of Basel (1431–47), and the failed Hussite crusades of the 1420s. Tradition also acted as a cloak: Holy Land formulae covered the use of the term cruciata, which actually meant standardised sales of indulgences.3

The Dukes of Burgundy

Secular support for crusading rested on popular devotional practices, aristocratic cultural identification and memories of past heroics, sustained in visual and material culture, history and imaginative literature. Political dividends were pursued in western Europe most strenuously by the dukes of Burgundy, Philip the Good (1419–67) and Charles the Rash (1467–77), son and grandson of the commander of the Nicopolis crusade, John the Fearless (duke 1404–19), both eager to break the shackles of their non-royal titles to assert an independent authority commensurate with their wide territories and immense wealth. As dukes of Burgundy, counts of Flanders and descendants of Louis IX, they stood as legatees of the grandest crusade inheritances, which they exploited loudly even if their material aid failed to match their belligerent rhetoric and ritual investment.4

Philip the Good sponsored intelligence-gathering trips to the eastern Mediterranean, such as Guillebert de Lannoy’s in 1421. He employed crusade experts such as Bertrandon de la Broquière (d. 1459), who scrutinised the Greek diplomat John Torcello’s crusade advice to Eugenius IV in 1439 and in 1457 published his own memoirs of his travels around the Near East in 1432–3, during which he had met Sultan Murad II.5 Another Burgundian courtier, Geoffrey of Thoisy, campaigned in the eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea between the 1440s and 1460s. He wrote a memorandum on anti-Turkish war in the early 1460s as did another Burgundian veteran of the Ottoman conflict, Waleran of Wavrin. Jean Germain, bishop of Chalon-sur-Saône (1436–61), acted as the Burgundian court’s resident commentator on crusade involvement from the 1430s to 1450s. He served as chancellor of the Order of the Golden Fleece, founded n 1431, which laid on the Feast and anti-Turkish Vow of the Pheasant at Lille in 1454. Another chancellor of the Order, William Filastre, bishop of Tournai, led crusade discussions with Pius II in the 1460s. For half a century, the Burgundian court entertained crusade planners, such as John of Capistrano, and voiced enthusiasm for proposals. Duke Philip played a prominent part in crusade diplomacy after the fall of Constantinople and in the 1460s. Church taxes were regularly levied and indulgences sold. Philip supported both Iberian and anti-Hussite crusading. Small squadrons of galleys were sent to Rhodes (1429, 1441, 1444) and Constantinople (1444–5), and a regiment despatched to Ancona to aid Pius II’s crusade in 1464. Duke Charles maintained the dynastic commitment that was continued by his grandson, the emperor Charles V, who combined the Burgundian crusade tradition with his Spanish reconquista inheritance.

However, Burgundy’s failure to convert showy enthusiasm into effective policy suggested a changing role for crusading that now competed with parallel forms of civic devotion, with kingdoms proclaiming their status as new Israels, holy lands in their own right, their defence a moral priority. The Burgundian court’s engagement followed a ritualised pattern of diplomatic expectations. The dukes raised crusade money and promoted nostalgic fancies of recovering the Holy Land, yet declined major unilateral investments in conflicts in eastern Europe, the Adriatic or Aegean. France, England and western Germany always posed more immediate problems than the Turks. Burgundian rhetoric and emotion appeared driven by history not future conquests; John of Capistrano discussed the recovery of Jerusalem on his visit in 1454. The extent of popular engagement is hard to assess, although local recruitment initiatives bore some fruit in the 1450s and 1460s: for example, in March 1464, eighty men from Ghent took the cross.6 Even at court, commitment could appear divorced from mundane serious war planning. The Vow of the Pheasant (1454) represented displacement: theatrical ducal glorification not a policy to recapture Constantinople. This was not, as it could have been, a ceremony of taking the cross. Only a very few volumes among Duke Philip’s considerable collection of crusade texts even dealt with the Turks.7 The supposedly practical information contained in Broquière’s memoir of his Near Eastern travels was twenty-five years out of date. Escapist theatricals were not necessarily cynical or mendacious, but reflected only a general conceptual frame not a political revival.

Popular Responses

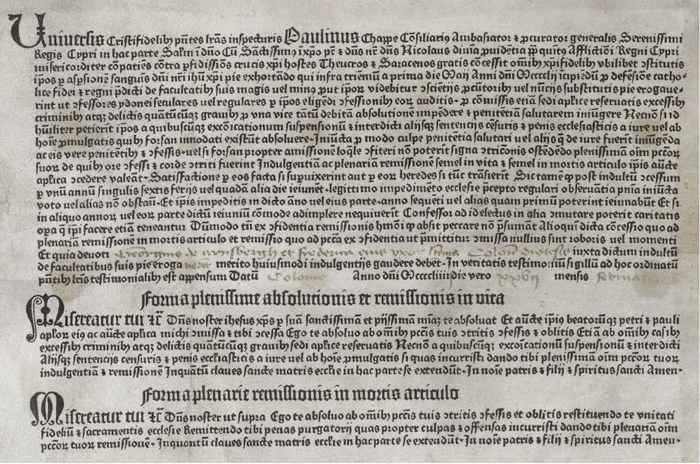

Evidence for social engagement with crusading came from the popularity of buying indulgences, now a bureaucratised international system of purchasing spiritual privileges of absolution, either immediate or on the point of death. Prices were not insignificant. In Germany around 1500 an indulgence cost about a week’s household expenditure. In 1501 in England, rates varied: on property, a sliding scale charged the richest 0.16 per cent of estimated income to 0.33 per cent for the least wealthy; on non-property income rates were more consistent at about 0.2 per cent, i.e. a few shillings to a few pounds. Money from other indulgence sales, such as those for the increasingly regular papal Jubilees (1450, 1475, 1500, etc.) could be diverted to the crusade or, more generally, to defence against the Turks. In England between 1444 and 1502 twelve such indulgence drives were conducted. Although receipts could be modest – hundreds rather than thousands of pounds a time in England – perceptions that large sums were being drained out of the nation became standard, especially in Germany.8 Indulgence campaigns quickly exploited the new technology of printing. Previously written on durable vellum, indulgence forms now appeared as printed pro forma sheets, with blank spaces kept for the names of the beneficiaries to be filled in by hand. The earliest surviving examples date from Mainz in 1454/55. Printers began producing them in batches of hundreds a day. In England from the 1470s, the top pioneer printers, William Caxton, John Lettou, Wynkyn de Worde and Richard Pynson, all took advantage of this lucrative staple of their business.

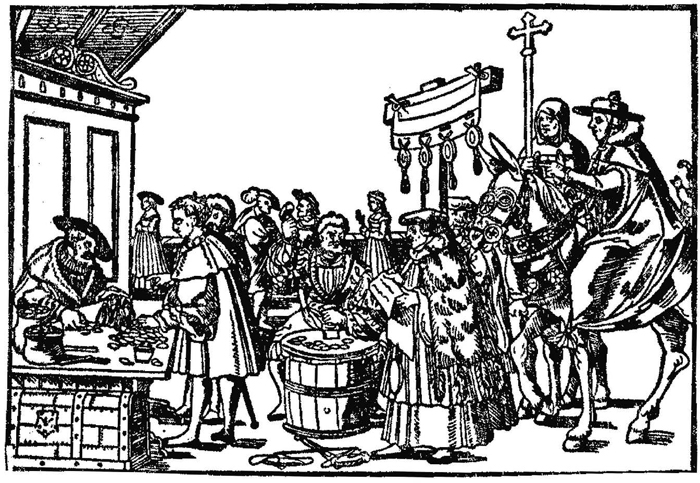

143. Money being assembled to pay for indulgences.

144. A Gutenberg indulgence from 27 February 1455.

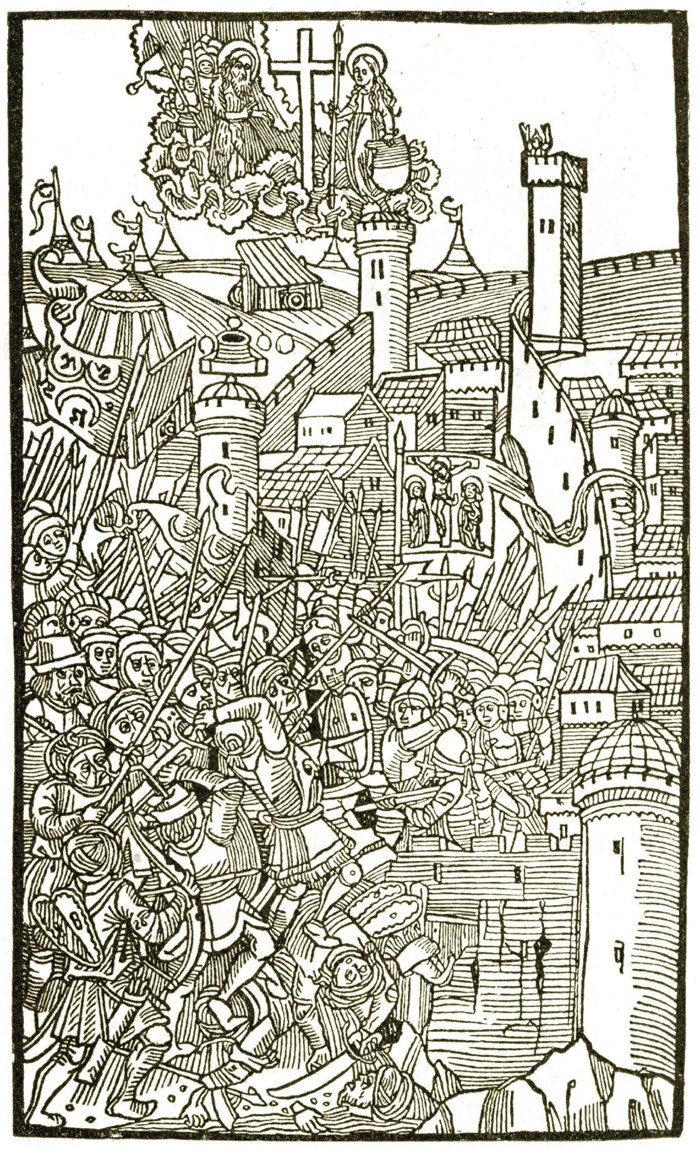

Printing accelerated the speed and widened the reach of the circulation of news, ideas and crusade texts: sermons, treatises, poems, popular songs, pamphlets, public correspondence, newsletters and devotional works. The new technology allowed for the inclusion of woodcut illustrations to add vivid immediacy and mould public perceptions. Whereas Cardinal Bessarion’s Latin Orationes (1471, see p. 409), prompted by the loss of Venetian Negroponte in 1470, attracted a print run of fewer than one hundred copies, William of Caoursin’s lively account of the siege of Rhodes (1480), also originally in Latin, with its array of striking woodcut images, became a best-seller, with editions published between 1481 and 1489 in Venice, Ulm, Salamanca, Paris and Bruges. An English translation appeared in London by 1484.9 Printing stimulated translation generally. In 1481, Caxton produced an English version (from the French) of William of Tyre’s account of the First Crusade (the first nine books) under the title Godfrey de Bouillon. Pynson published a translation of the early fourteenth-century encyclopaedic crusade treatise and Asian gazetteer, the Flowers of the History of the East, by the Armenian Hetoum of Gorigos in 1520. The Middle English romance, Capystranus, commemorating the 1456 defence of Belgrade, appeared in numerous editions, fragments surviving from 1515, 1527 and 1520.10 The first century of European printing massively increased the volume, availability and social reach of material on the crusade and the Turkish threat, reflecting what was believed to be popular. The literary confections of fifteenth-century Italian humanists appealed to a narrower audience than the more demotic, often garishly illustrated, front-line German pamphlets, the Turkenbüchlein and Flugschriften of the 1510s to 1540s.11 However, in their respective spheres, both offered debates on necessity, urgency, legitimacy, efficacy and conduct of crusading to social groups beyond traditional political, ecclesiastical and academic hierarchies.

Despite the absence of regular mass cross-taking, the ceremony remained available in various different versions across Christendom. Innocent VIII (1484–92) included a revised formula in his Roman Pontifical that reflected current practice by describing the cross being taken ‘to assist and defend the Christian faith or the recovery of the Holy Land’.12 Cross-giving still featured prominently in high-profile fifteenth-century crusade initiatives, including Cardinal Carvajal’s legation to Hungary in 1455–61 involving John of Capistrano, and Pius II’s crusade.13 Crucesignati fought with the Hungarians against the Turks in 1458 and with Matthias Corvinus in Bosnia in 1464. Recruitment centred on towns, even if quite modest ones, such as Axel in the Netherlands. Individual examples of cross-takers continued. Some, such as two Norwich worsted weavers in 1499, were hardly grand.14 However, recruitment of non-professional troops scarcely met the needs of generals or politicians, a familiar gap between expectations and practice. The infrastructure to generate enthusiasm and stimulate anxiety remained available in liturgies, Masses and processions while crusading was still promoted as a metaphor for Christian behaviour.15 In Hungary in 1514 the tension between popular expectations and the reality of crusade politics even helped ignite social revolt. Recruited by anti-Turkish preaching, an army of cruce-signati from poorer marginal sections of the community, eager to believe the militant revivalist rhetoric, confronted the prudent caution of nobles more interested in diplomatic accommodation and crusade money and reluctant to divert their workforce from their lands.16 The ensuing atrocities and extremes of violence from both sides pointed to how the crusade could excite unrelated social tensions.

145. Woodcut of the siege of Rhodes, 1480.

Cross-taking rituals became increasingly obsolete as preaching was divorced from raising men. The last time the cross was generally preached in France may have been in 1517–18. In Germany, between 1486 and 1504, an energetic crusade proponent, Cardinal Raymond Perault (1435–1505), emphasised the infidel menace to Christendom and Christian souls: but he was there to sell indulgences.17 As a fiscal mechanism, the system inevitably invited abuse and attracted criticism, courting rulers’ hostility except, as in Spain, where they secured a monopoly over proceeds. Imagery of the cross of redemptive violence still resonated, not least with the cultural aspirations of Roman Catholic nobilities. Preachers and pamphleteers continued to thunder against Ottoman threats to Christendom and Christianity. Yet by the end of the fifteenth century, for most of the faithful, the crusade bypassed religious passion, reduced in practice to a bureaucratic process by which money or goods were handed to Church or State to be used more or less at will. The inherent dangers of corruption, incompetence, and the distance between oratory and action invited indulgence fatigue, a problem identified as early as the 1270s.18 The fifteenth century witnessed a paradox: indulgences continued to be bought extensively while official perception of disenchantment mounted, provoking Pius II’s remark that crusade preachers had become ‘like insolvent tradesmen . . . without credit’.19 Between 1458 and 1523 the German Reichstag regularly questioned the use of crusade money. Suspicion undermined Perault’s preaching in Germany around 1500. Leo X’s attempts to fund a new crusade were dismissed by Francis I of France in 1517 as ‘clever tricks to extract money’, adding that ‘the people’s devotion is so small that almost nothing will be raised’.20 Such disenchantment charted the distance between traditional popular enthusiasm for holy war, as it became generally known in the sixteenth century, and its more complex political and military reality.

New Worlds

The expansion of Iberian kingdoms into and across the Atlantic exposed different features of religious violence, some not specifically crusading. Traditional crusade ideology and institutions remained integral to Iberian national identities, notably in Castile where the culture of reconquista suffused popular romances, matching an economy of plunder. Continuing inter-faith conflict on the peninsula and in north Africa attracted standard crusade incentives and finance.21 To improve their appeal, indulgences were offered at decreasing flat rates and, after 1456, open to souls in purgatory. Although often placed in the context of the international conflict with Muslim powers, with Sixtus IV in 1482 explicitly equating the Granada campaign with wars in the Holy Land,22 Iberian crusading remained distinct. The reconquista tradition persisted in Spanish and Portuguese wars to annex Morocco and Tunisia into the later sixteenth century with the Spanish conquest of Tunis and the disastrous Portuguese invasion of Morocco in 1578. Even if driven primarily by incentives of martial glory, commerce and African gold, these north African wars could be presented in traditional terms of Christian defence and recovery. They could also be promoted as opportunities for conversion. Despite the canon law prohibition on forced conversion, since the twelfth century some had seen crusading as enabling the extension of the faith, dilatatio fidei. Sixtus IV’s 1482 Granada bull linked defence with the spread of Christian faith and conversion.

Castilian and Portuguese expansion in west Africa and the Atlantic islands could not be justified in terms of recovery or defence of Christian land, but canon law going back to Innocent IV in the thirteenth century allowed for the conquest of pagans who resisted missionary work. More contestably, some defenders of Iberian Atlantic conquests deployed concepts of racial inferio-rity and innate barbarism to deny indigenous populations political agency or even independent human rights.23 This racist argument was not the monopoly of Iberian apologists, mirroring humanist depictions of Ottomans as barbarians beyond the pale of civilisation, in Pius II’s word, immanis, inhuman.24 Denying autonomous rights to indigenous Atlantic and American pagans pointed to fundamental differences between conquest in the New World and crusading in the Old. Despite arousing conventional crusading emotions and rhetoric, wars in the Canaries or later the Americas could only be related to the reconquista or the Holy Land by distant analogy. Christopher Columbus imagined his voyages in the context of the recovery of Jerusalem.25 In Mexico, Hernán Cortés compared Tlaxcala with Granada. This generic crusading identification helped incorporate the New World into familiar cultural patterns of the Old, but there were no crusades in America, a point reinforced by Alexander VI’s bull Inter cetera in 1493 that gave the Spanish monarchs the right to conquer and rule native Americans. Alexander, a veteran of Pius II’s Turkish crusade schemes of the 1460s, based his grant on the pope’s duty to protect all mankind. He insisted that Spanish conquest be aimed at conversion not material exploitation. Alexander’s concern to base the right to dominion on the promotion of conversion followed Eugenius IV’s precedent in 1436 over the Portuguese annexation of the Canaries rather than Nicholas V’s grant in 1455 allowing the Portuguese to conquer and enslave the infidels of Africa. Although citing the recent end of the Granada war, Inter cetera did not proclaim a crusade in the New World. It was in any case immediately rendered redundant by the treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 that carved up the globe between Spain and Portugal without papal approval.26 European colonisation was pursued under Christian banners and furthered by Christian missionaries and ecclesiastical settlement, but, unlike conquests of pagans in the Baltic, independent of direct papal authority and without the use of the crusade. The crusade only reached the Americas as a region of the Spanish Empire subject to cruzada taxation. It has been argued that only the speed of Spanish conquests prevented grants of crusade privileges.27 This is contradicted by the early date of Inter ceteros and subsequent rejection of crusade precedents for the Americas despite crusade bulls for the Spanish in the Mediterranean and the Portuguese in the western Atlantic. The Spanish do not seem to have requested crusade privileges, despite trading on equivalent religious emotions or psychology. As contemporaries noticed, the conquistadors’ chief driver lay in unabashed material gain, conversion acting as a weapon of conquest.

146. Cross and conquest: a late sixteenth-century depiction of Columbus in Hispaniola.

In the absence of crusade certainties, doubts concerning the conduct and legitimacy of New World conquests revived late medieval debates over just war and infidel rights. The Dominican theologians and canonists Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566) and Francis Vitoria (1492–1546) asserted Amerindian human rights with arguments derived in part from thirteenth-century canon law on the crusade and just war even if Vitoria, for instance, rejected the appropriateness of traditional crusade categories. Others, more wedded to reassuring self-serving conservatism, sought to brand Amerindians as fair game for subjugation, analogous to Turks and Muslims or as uncivilised natural slaves.28 Despite legal arguments familiar to late medieval crusading, and although American conquests indulged ambitions previously associated with holy warriors, conquistadors were not crucesignati. The absence of the crusade in America signalled its irrelevance to the most important and transformative new area of Christian war, conquest, mission and expansion since late antiquity, marking a break with the past and a lessening of crusading’s role in Christian society.

The Protestant Challenge

The diminishing of the crusade was further accelerated by the combat against the religious reformers of the sixteenth century. The reformist Christian opponents of the Roman Catholic Church presented a fundamental critique of the crusade’s ideology and devotional practices. As such, like the fifteenth-century Hussites, they offered obvious targets for traditional crusading. However, these opportunities were only equivocally pursued, perhaps as a result of the previous century’s experience. The use of crusades against dissident Christians and political opponents by opposing sides during the papal schism had undermined the credibility of crusading as a tool of secular statecraft. Nicholas V’s offer of crusade indulgences to Charles VII of France for an invasion of Savoy, the county of anti-pope Felix V (1439–49), led nowhere.29 Julius II’s (1503–13) renewal of Italian crusades and his grant of crusade status to Henry VIII of England’s invasion of France in 1512 proved eccentric not prescient.30 Nonetheless, after 1417, the restored papacy had continued to approve crusades against heretics: the Hussites in Bohemia or the nasty little crusade in 1487–8 against Alpine communities of Waldensians.31 Inevitably, new schemes for crusades against the reformers were floated: against Henry VIII of England in the 1530s and Elizabeth I after her excommunication in 1570; German Protestants in the 1540s; or in favour of Irish Catholic resistance to Protestant English rule between 1577 and 1600. In 1536, Lord Darcy, a leader of the English Catholic traditionalist uprising the Pilgrimage of Grace, supplied the rebels with badges of the Five Wounds of Christ originally manufactured for a planned campaign to Morocco in 1511. Indulgences to fight ‘foes of our holy faith’, as those granted to the English privateer and veteran of Lepanto, Thomas Stuckeley, in 1575 by Gregory XIII (1572–85), could as easily be applied to Ireland as to north Africa: in the event Stuckeley died at the battle of Alcazar (1578).32 Sixtus V (1585–90) based his indulgences for the Spanish Armada against Elizabeth I of England (1588) on those issued for fighting the Turks by Gregory XIII in 1585, complete with Holy Land remissions, an association included in Gregory XIII’s earlier 1580 indulgences to Irish opponents of Elizabeth I. Protestants were frequently demonised as agents of Anti-Christ, similar or worse than Turks, impediments in the struggle with the Ottomans.

147. The badge of Five Wounds of Christ worn during the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536.

Yet no general anti-Protestant crusade was launched. Politics trumped religion. Competition between the Habsburgs and the kings of France, the divergent interests of Spain, religious divisions within France and the German Empire, and Catholic princes’ suspicion of papal authority, prevented a united front against English or German reformers. Holy war was by no means dead. Inspired by Old Testament precedent, Protestants could argue from scripture for direct divine approval of war for the faith, shorn of Roman Catholic theology and penitential accretions. Roman Catholic devotees maintained the crusade tradition, its mentality, language and forms apparent during the French Wars of Religion (1562–98). Defenders of Toulouse against Huguenots in 1567–8 wore white crosses and were given plenary indulgences by Pius V to create a militia or association (sodalitium) of cruce-signati.33 Yet these local instances merely emphasised the crusade’s absence on a grander scale, conforming to counter-Reformation Roman Catholicism’s increased concentration on individual as well as communal devotional practice. As with the conquests in America, anti-Protestant wars provided alternative non-crusading expressions for fighting for the faith. There were no crusades in the great confessional confrontation of the Thirty Years War (1618–48).

148. Spanish Armada of 1588, with a ship flying the flags of Spain, the papacy and the crusaders’ cross.

149. An English Knave of Hearts playing card showing the pope paying for the Spanish Armada.

Crusade and Nation

Throughout the later Middle Ages, as kingdoms developed greater political and administrative articulation, the nation increasingly provided a focus for a sense of divinely ordained and protected community parallel to that of Christendom, a process stimulated by cults of monarchy and national exceptionalism. During the Hundred Years War, both English and French propagandists projected images of national providence, one English bishop in 1377 claiming in Parliament that English victories in the French wars proved that God ‘as he did Israel’ had chosen England ‘as his heritage’. The red cross of royalist crusaders in the 1260s became the badge of later medieval English soldiery.34 Assertion of a crusading reputation, a feature of royal propaganda since the twelfth century, continued in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: Emperor Frederick III of Germany (1440–93) taking the cross and holding crusade Diets after 1453; Matthew Corvinus of Hungary using his own and his father John Hunyadi’s crusading credentials to bolster his parvenu dynasty; Emperor Charles V fighting Turks, Protestants and conquering Tunis; the claims of Hungary and other eastern European, Balkan and Italian principalities for special treatment as Christendom’s bastions, antemurales. National pride attached to crusade heroes: Richard I in England; Louis IX in France; Baldwin IX of Flanders in Flanders/Burgundy; the champions of the Iberian Reconquista. Philip II of Spain’s messianic insistence that Spain’s wars were God’s wars witnessed perhaps the most strident transfer of crusading ethos into national holy war.

The nationalisation of crusading found reflection in literary commentary. While fifteenth-century Italian humanists tended to use the crusades to discuss the idea of a threat to western post-classical Christian civilisation as a whole, by contrast, Christine de Pisan’s Ditié de Jehanne d’Arc (1429), in language saturated with familiar crusade tropes (‘He who fights for justice gains Paradise’; ‘God wills it’), elevated the French monarchy to God’s providential favour (‘He finds more faith in the royal house than anywhere else’), confirmed by the deeds of Joan of Arc: a restored Charles VII (1422–61) would recover the Holy Land. For Christine, heaven was the reward for those who fought just wars for the patria.35 Each side in the Hundred Years War was claimed as the new Israelites. The Gesta Henrici Quinti (1417), by one of Henry V’s chaplains, describes English soldiers the night before Agincourt (1415), as ‘God’s people’, like the Maccabees, donning ‘the armour of penitence’. A Te Deum is ordered by the king ‘to the praise and glory of God Who had so marvellously deigned to receive His England and her people as His very own’. Henry, ‘God’s knight’, rules ‘his people Israel’.36 This sanctification of the secular world was not confined to Catholic orthodoxy. The Czech Hussites created a new holy landscape in Bohemia, including a Mount Tabor and a Mount Horeb, to express their national religion, the association with Old Testament Israel demonstrating a clear rejection of the crusades launched against them. Such sanctified patriotism mirrored crusading. Armies took the sacrament, spoke the general confession and received absolution before battle. The cross became an increasingly common military uniform for national armies (red for the English and troops of the Habsburg emperors) and popular insurgents, such as the German peasant rebels in 1524–5 and, according to one observer, the English Pilgrimage of Grace in England in 1536. Precise crusade association may have faded, yet the cross’s religious significance in symbolising particular communal solidarity remained. Soldiers of the Swiss Confederacy wore white crosses against Burgundy and the Habsburgs. So did the defenders of the Florentine Republic, a city with long crusade credentials, described in the 1490s as a New Jerusalem. As a banner of armed struggle, the iconography of the cross was unmistakable.37

150. El Greco’s Adoration of the Name of Jesus, c. 1578, an allegory of the union of Spain, Venice and the papacy against the Turks; Philip II of Spain is the kneeling figure in black at the front.

With crusade images recruited to wars for the patria, academic study adopted a nationalist tinge, not least in regions of religious contest, Germany and France. The French Huguenot Jacques Bongars (1554–1612) produced a massive edition of crusade chronicles and texts, Gesta Dei Per Francos (1611), the most significant single tool for crusade research until the nineteenth century. Explicitly in the preface and implicitly in choice of texts, Bongars was praising the crusading tradition of France and its Roman Catholic monarchy (as a diplomat he was employed by the convert Henry IV), annexing the crusade to a supra-confessional national myth. A French translation of William of Tyre in 1574 was titled Histoire de la Guerre Sainte, dire proprement, La Franciade orientale, while the encyclopaedist Etienne Pasquier in the 1590s, like Bongars, associated the Holy Land wars with ‘la grandeur de nostre France’.38 This French literary enthusiasm was maintained during the seventeenth century, not least under Louis XIV with such royalist Francophile works as Louis Maimborg’s History of the Crusades (1675), by which time crusading had become for all but a very few simply a matter of antiquarian curiosity and historiographical interest.

The Image of the Crusade

The fading of the crusade as a dynamic element in Christian society was slow and uneven. Its image retained force, through preaching, literature, communal memory and visible iconography long after calls to arms and offers of indulgences had become nugatory, remote, insincere or controversial. Vocabulary traced the transformation. In the fifteenth century, the word cruciata and related vernacular versions increasingly referred to fund-raising while war against the Turks assumed the general language of war such as bellum or expeditio.39 After Belgrade in 1456, few actual crucesignati fought the Turks. Yet the crusade continued to provide an ideal against which to assess political action and morality in the tradition of Philippe de Mézières’ response to the Nicopolis defeat of 1396, urging general spiritual regeneration as a precondition for Christian success.40 Blaming defeat on the pious deficiencies of crusaders or Christendom more generally retained currency, from works of advice to those of encouragement.41 The debate on collective moral deficiency was maintained both by Italian humanist crusade advocates and critics of military crusading such as, in the mid-fifteenth century, the Spanish John of Segovia and the German Nicholas of Cusa, or, two generations later, Erasmus of Rotterdam. The familiar uneasy literary relationship between historical commentary and political exhortation persisted.42 William of Tyre became the standard narrative, with numerous printed versions, including editions of the whole Latin text in 1549, 1564 and 1611, the Basel printer Johannes Herold’s De bello sacro (1549) (holy war being the near-ubiquitous name for the crusades in the early modern period; Herold was not a Roman Catholic) extending William of Tyre to the accession of Suleiman the Magnificent in 1520.

Herold’s hardly penetrating observation that religious divisions were obstructing resistance to the Turks became a common motif across confessional boundaries, as in the massive but popular Generall Historie of the Turks (1603) by the English Protestant schoolmaster Richard Knolles.43 Such common ground identified an aspect of Christian universalism that survived changing patterns of devotion. Although the crusades no longer dominated Ottoman wars or infra-religious Christian conflict, the fight against the Turks retained a generalised religious dimension in popular perceptions of Islam as more alien than other Christian confessions. Recognition of the moral as well as political benefits of war against the Turks was shared by Protestant and Roman Catholics alike, but shorn of the formal trappings of the crusade. Thus the great Roman Catholic victory at Lepanto in 1571, with all its hallmarks of crusading, could be welcomed by the young Calvinist James VI of Scotland in a long Virgilian epic (1585) as a ‘wondrous worke of God’, and was celebrated at the time by Protestant commentators and Londoners as a victory ‘against the common enemy of our faith . . . of so great importance unto the whole state of Christian commonwealth’.44

The often laudatory concern with the crusades shown by non-Catholic scholars indicates a final irony. Detoxified by its irrelevance to fighting the Turks or Protestants, study of the crusades was used to suggest cultural continuity across the confessional caesura of the Reformation either, by Bongars, in weaving the crusades into the national epic or, by Knolles, in projecting a view of Christian Europe as a ‘commonweale’ of princes defined not by religious disagreements but by collective opposition to Muslims. Even the English reformist polemicist John Foxe’s excoriating anti-Roman Catholic account of the crusades, History of the Turks (1566), noted the courage and religious devotion of ordinary Catholic believers in the wars against common enemies of Christ and Christendom, even if he insisted that ‘the Turks . . . were never so repulsed and foiled as at the present time in encountering with the protestants and defenders of sincere religion’.45 The Protestant challenge had destroyed universal acceptance of the religious systems behind traditional crusading but not the emotional attraction. Confessionally neutral concepts of holy war were fashioned that avoided arguments over crusading.

This did not mean universal agreement that holy war was any more justified than crusading, a point underlined in the English lawyer, scholar and politician Francis Bacon’s fragmentary Advertisement Touching an Holy Warre (1622–3; published 1629) on the legitimacy of ‘the propagation of the Faith by arms’.46 Bacon’s discussion, presented as a debate between contending intellectuals, rested on history and the new perspectives provided by the conquests of natives in the Americas. While famously having one of his protagonists describe the crusade as ‘a rendez-vous of cracked brains that wore their feather in their head instead of their hat’, Bacon’s treatment – what there is of it – is notably balanced.47 Rejecting wars for profit and crusading’s religious dogma, and suspicious of arguments based on necessity, prudence and law, Bacon’s presentation of the idea of a just war against the Turks nonetheless displayed familiarity with the legacy of the crusade. Religious wars continued to excite massive bloodshed far into the seventeenth century, in Germany, Britain and on frontiers with the Turk, but, despite an equivalence of emotional and psychological dynamics, it was not conditioned by the apparatus of the crusade. While individual crusaders still fought in the Mediterranean and eastern Europe for another century, and the Hospitallers maintained an increasingly lordly hold on Malta until expelled by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798, crusading as a vital element of public policy and private ambition dimmed into the margins of European experience, a gilded or reviled memory.