CRUSADING: OUR CONTEMPORARY?

No medieval events have possessed a more contested afterlife than the crusades. Few are more recognisable to modern audiences, in rhetoric and visual imagery. Later debates have become part of crusade history, classic examples of past events being shaped in retrospect. In western Europe and North America, the crusades have been perceived variously through the filters of Roman Catholic apologia, Protestant condemnation, nationalist appropriation, humanist materialism, Enlightenment disgust, Romantic empathy, imperial enthusiasm, modernist condescension and post-colonial disquiet. They have been seen as barbaric invasions, conduits of economic development and cultural exchange, transmitters of European supremacy, witnesses to spiritual devotion, expressions of religious bigotry, acts in a cosmic clash of civilisations or squalid self-interested land-grabs. The heirs of victims and opponents share some of these opinions, but add particular elements of inherited outrage, anger, bitterness, disgust and sadness. The crusades have transcended historiography to find a place in popular culture, in operas, novels, elite art and public monuments, but also in children’s books and folklore, Arabic as well as western. From literature and art to entertainment and politics, the crusades have long possessed power to inspire or appal.

The crusades attracted, in David Hume’s phrase, ‘the curiosity of mankind’ both for their role in international mayhem and for the startling emotional paradox of religious violence presented as an act of charitable love.1 The duopoly of materialism and idealism has provoked judgemental assessments: were the crusades aberrant, malign, eccentric or, in some ways, central to the European experience, of ‘limitless effect’?2 Interpretations since 1600 have mixed admiration, revulsion and astonishment. Words for the crusades became lodged in modern vernaculars. By the eighteenth century, descriptive terms Kreuzzug or croisade replaced the generically neutral ‘holy war’ in Germany and France, while in Spain, the bula de cruzada remained a living part of the fiscal system. Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary (1755) included four words for the phenomenon – crusade (of early eighteenth-century coinage, later popularised by Hume and Gibbon), crusado, croisade and croisado. By the mid-eighteenth century, ‘crusade’ also began to be applied analogically to campaigns for good causes or issues of principle (e.g. J. G. Hamann’s Die Kreuzzüge des Philologen [Crusades of the Philologian], 1762; Voltaire’s croisade against smallpox, 1767–8; Thomas Jefferson’s ‘crusade against ignorance’, 1786). Such awareness owed more to imaginative literature than to academic disputes or scholarly accuracy, as does much modern appreciation.3

Accounts of the crusades had always straddled the fine line between history and fiction. Probably the most influential early modern work was Torquato Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata (1580–1), which translated the story of the First Crusade and Godfrey of Bouillon into an epic of chivalric romance and magic, creating an exotic never-never land of amorous crusaders and Muslim warrior maidens ripe for love, death and conversion. Although hardly liable to be confused with the sober historical accounts being written at the time, Tasso’s work, regularly republished and translated, distanced the image of crusading from its involvement in urgent contemporary concerns with papal authority or the Ottoman threat. Placed in a fantastical space available to imaginations free from historical, confessional or political constraints, owing as much to Renaissance classicism as to medieval religious war, Tasso’s romance, by taking the crusades out of the council chamber, scholar’s library and pedant’s schoolroom, offered a sentimental perception that reduced the crusades to exotic (and often erotic) adventure stories seen through a soft-focus western lens. The impact was immediate and far reaching. By 1639, the Englishman Thomas Fuller’s influential, critical Historie of the Holy Warre was seen by one enthusiast as robbing Tasso’s poem ‘of its long-liv’ed glory . . . Thou canst not feigne so well as he relate.’4 This proved optimistic. Tasso’s legacy penetrated far into the mortar of European high culture, inspiring music by Monteverdi, Lully, Handel, Vivaldi, Gluck, Haydn, Rossini, Brahms and Dvořák, and paintings by Tintoretto, Poussin, van Dyck, Tiepolo and Delacroix. In literature and, later, film, Tasso’s influence was profound, part of a lasting unequal exchange between the popular and the learned.

151. The crusades through Tasso’s lens: Poussin’s Rinaldo and Arminda.

Crusades and Progress

Given such dramatic raw material, it is unsurprising that historians have incorporated the crusades into wider patterns of European experience. For Thomas Fuller and savants of the earlier seventeenth century, the crusades addressed issues of immediate significance: the expression or corruption of faith; the materialism behind the crusade’s emphasis on possession of physical space; the advance of the Turks. Waste formed a common theme, the crusades being blamed for a dissipation of resources that led to the decline in traditional aristocratic power and the rise of national monarchies. Perspectives shifted with the decline of the Ottomans as a political threat after the repulse of the siege of Vienna in 1683 and confirmation of Ottoman retreat at the end of the Turkish war in 1699. The eradication of religion as a stated cause of European war after the end of the Thirty Years War; the expansion of European trading and colonial empires from the Americas to the East Indies; and increased European commercial penetration of the Mediterranean and Levant – led to a reformulation of the crusades into a story of contact and exchange. This materialist turn was signalled in the influential Discourse on Ecclesiastical History (1691) by the French lawyer, priest, theologian and church historian Claude Fleury. Avoiding confessional point scoring or patronising the past, Fleury identified, beneath the wars and conquests, the growth of navigation and commerce. This afforded Italian merchants in the Mediterranean ‘freedom of trade’ (liberté du commerce), starting a commercial revolution that led to an urban renaissance in arts, manufacture and industry.5 This positive if accidental material consequence allowed the crusades a place in the construction of progressive modernity and European global hegemony.

Subsequent intellectual debates pursued Fleury’s themes in contrasting ways. The new European global reach and the retreat of Ottoman power inspired greater interest in Arabic and non-European sources in confident accounts of the rise of Christian Europe and their opponents; accounts of the crusades using Arabic texts were integrated into a much wider materialist narrative of Eurasian invasions and cultural exchange devoid of nationalist or moralising charge. Within a general materialist consensus, no united ‘Enlightenment’ view of the crusades existed. The French philosophes, Denis Diderot and Voltaire, decried the crusades’ superstition and irrationality, using them as oblique criticism of the manners, culture and pretensions of the ancien régime. Implicitly, crusaders’ superstition, hypocrisy, greed and imposition of social inequality were analogous to the conduct of their modern aristocratic heirs. This negative assessment was far from unchallenged. Although few were more acidly hostile to the whole crusade phenomenon than David Hume, his Scottish associates, William Robertson, Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson, integrated the crusades into a persuasive account of the rise of western Europe. In the introductory chapter to his History of the Reign of Charles V (1769), ‘The Progress of Society in Europe’, Robertson, like Fleury, argued that the crusades, despite their superstition and folly, inadvertently produced increased international commerce, cultural exchange with the sophisticated east and the growth of western cities, which fostered civic values fundamental to the improvement of civilisation. Thus to the crusades ‘we owe the first gleams of light which tended to dispel barbarity and ignorance’.6 Robertson apparently derived this idea of economically determined progress directly from Adam Smith’s lectures, just as his observations on beneficial cultural borrowing were taken from Ferguson’s Essay on the History of Civil Society (1767). The contrast with the French philosophes lay in the different contemporary targets. In France, Voltaire and Diderot were confronting an illiberal, reactionary hierarchy under a divine-right monarchy whereas in Scotland Robertson and Smith were analysing a society that had seen rapid and, they would have argued, positive developments in the economy and legal, religious and political freedom, seen by them as the fruits of the Act of Union with England (1707).

However, this Smithian concept of progress was not universally accepted even by anglophone writers. Gilbert Stuart’s View of Society in Europe (1778) turned Robertson’s economic argument on its head by insisting that the material and human waste in Europe caused by the crusades actually discouraged trade and the development of the civilising arts while simultaneously pro-moting superstition. The Robertsonian scheme of progress was similarly rejected by Edward Gibbon in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (the chapters on the crusades were published in 1788). In a pointed phrase, Gibbon insisted that the crusades marked ‘the final progress of idolatry’, the material advances that came in their wake insignificant and peripheral.7 Yet Gibbon accepted the orthodoxy that the crusades in some measure contributed to the rise of independent cities and hence to a growth of liberty. The idea that the crusades contributed positively to the development of European civilisation and its global dominance became an academic orthodoxy across western Europe by the end of the eighteenth century, helped by the absence of any serious attempt to analyse, still less empathise or understand the religious motivations. Academic prizes were offered for theses supporting positive materialist interpretations, which were lent apparent credence by the consolidation of European world empires, and the American, French and early industrial revolutions. Each appeared to demonstrate a progressive tendency in the historical process from which the crusades could not be excluded. Moral judgements were relegated to a series of Enlightenment or neo-Protestant clichés of bewilderment or disapproval only balanced by recognition of the crusaders’ commitment and bravery, however misguided.

French Romance and Empire

Such academic discussions, aimed at using history instrumentally to explain the modern world, operated in parallel to a very different approach. Even before the French Revolution exposed for many the aridity and cost of the cult of Reason and its Enlightenment apologists, a very different literary response to the Middle Ages had flourished. Beyond the intellectual salon, customary religion still played a central role in popular attitudes to history. Interest in the social aspects of the medieval past, such as chivalry, remained lively in aristocratic circles on many levels from the literary and antiquarian to the nostalgic and snobbish. Study of medieval literature produced fanciful pictures of chivalric hierarchy, codes of honour, valour and public service, with bold and selfless knights errant defending the weak or embarking on crusade. Chivalry could be depicted as tempering the barbarism of a violent militarist society, an agent of progress towards post-medieval civility, a secular code of moral behaviour contrasted with the supposedly ignoble materialism of modern society. Such sentimental evocations of medievalism were more closely attuned to public impressions than rarefied academic debates. The imagined Middle Ages offered an escape, an antithesis to modernity. At the same time, the crusades touched current concerns: empire; the relative cultural power of Europe; religion in secular society; mass support for popular political causes. The branding of the crusades as central to the development of European society could thus ally with conservative empathy for a lost world of social and religious certainties.

This combination of materialist and empathetic assessments of the crusades directed the revival of interest in the nineteenth century. One of the most influential champions of the crusades, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848) had read Robertson’s Charles V essay on progress (translated into French in 1771). The context was propitious for a revival of crusade enthusiasm as Napoleon’s extravagant campaign in the Levant in 1798–9 led to renewed interest in the crusading past. A Roman Catholic re-convert and royalist, Chateaubriand’s romantic evocation of the crusades in his account of his Near Eastern travels in 1806 (Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, 1811) combined religious empathy with pride in ‘French’ crusader achievements. In his Génie de christianisme (1802), Chateaubriand had insisted that Christianity itself, pace Enlightenment thinkers, played a central role in furthering the progress of arts and learning. Chateaubriand expressed a visceral, patronising dislike of Islam, offering a clear message that the crusade presented an admirable precedent for new western conquests in a decadent and impoverished Levant. The crusade soon became a central event for conservatives as well as progressives, widely accepted as ‘one of the greatest revolutions that has ever taken place in the history of the human race’.8

This view was shared by another French conservative, the former publisher Joseph-François Michaud (1767–1839), whose monumental epic narrative Histoire des croisades (1811–22, revised until a final posthumous edition in 1841), supplemented by his collection of translated sources Bibliothèque des croisades (1829), recast the crusades as moral exemplars of devotion and heroism, of Christian values and European cultural dynamism. A populariser with an ear for historical romance (he was not above using Tasso as a primary source) and eye for political uses of history, Michaud, like Chateaubriand, wrapped his francophile analysis in a sheen of cultural supremacism. Islam was cast as the eternal enemy, the Near East as ripe for new French colonisation and the crusades as part of an age-old conflict between civilisation (Christian Europe) and barbarism (the Muslim east). Armed with the appeal of an exciting story, extensive if uncritical and sometimes distorting employment of primary sources, a novelist’s power of credible invention, a clear moral tone and an attractive conservative political agenda, Michaud’s influence spread beyond Imperial and Restoration France. His Histoire ran into nineteen editions in the nineteenth century as well as translations into English, German, Italian and Russian. His vivid prose, along with Gustave Doré’s wonderfully powerful illustrations to the 1877 edition and the crusade paintings – essentially illustrations of Michaud – commissioned from 1837 by Louis Philippe for his Salle des croisades at Versailles, could be said to have provided the modern image of the crusades and crusaders, recognisable two centuries after Michaud began to mine the crusades for publishing profits.

152. King Louis Philippe and family visiting the Salle des Croisades at Versailles in 1844, with Merry-Joseph Blondel’s Surrender of Acre to Philip Augustus and Richard I in the background.

153. Blondel’s Surrender of Ptolemais [Acre] to King Philip II Augustus of France and Richard Lionheart on 13th July 1191.

Partly thanks to Michaud, the marshalling of the crusades to create patriotic myth was especially prevalent in France. The irony of using a quintessentially supranational cause to promote national identity was largely lost. One less meretricious consequence of the nationalist turn was the encouragement given to academic study of crusade texts, notably the monumental collection of western and eastern sources published as the Recueil des historiens des croisades (1841–1906). The purpose was explicitly nationalist: ‘France has played such a glorious part in the wars of the crusades that the historical documents that contain the accounts of these memorable expeditions seem to enter her domain.’9 The focus on the ‘colonies chrétiens en Palestine’ was equally deliberate: Spain, the Baltic or the Albigensian crusades were absent. The crusades were harnessed to the chariot of French cultural and political imperialism, Outremer – ‘La France du Levant’ – studied by French scholars for the next century and more as a precursor to modern colonisation. The tradition of imagining the crusaders as prototype French colonists reached a zenith under the Third Republic (1870–1940), eager to assert an imperial destiny to distract and unite a fractious, divided political nation. French historians identified supposedly typical ‘French’ elements in the buildings and social systems of Outremer. The post-First World War French mandates in Syria and Lebanon invited further parallels. Academic arguments for the existence of a Franco-Syrian society in Outremer reflected concurrent French settlement in Algeria as much as anything medieval. Into the twentieth century in France, as elsewhere, the crusades attracted writers of nationalist, conservative, Roman Catholic or right-wing persuasion. It took a Marxist, Claude Cahen, to debunk the westernised approach to Outremer history in his monograph using Arabic as well as western sources, La Syrie du Nord à l’époque des croisades (1940).

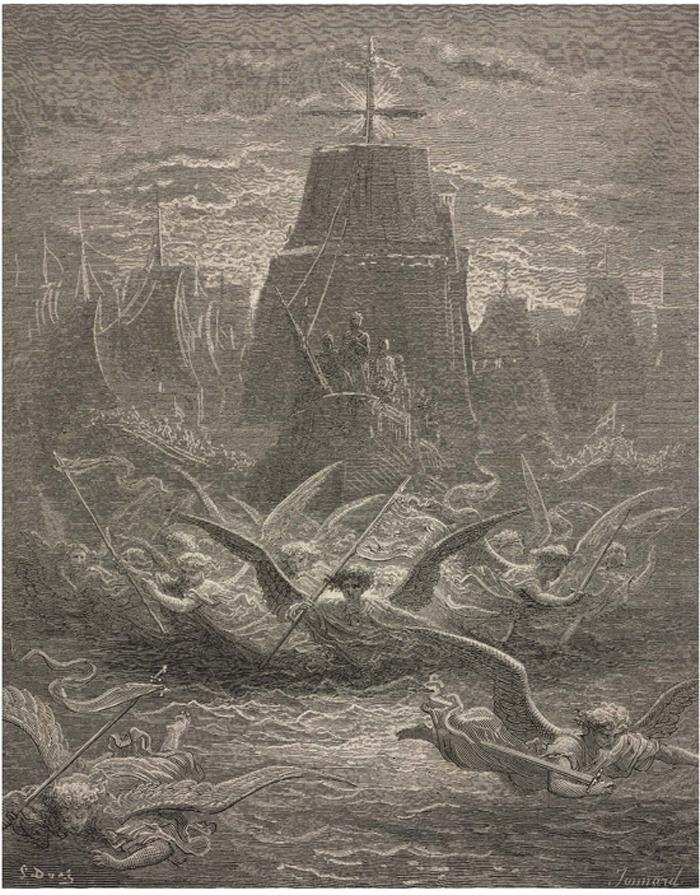

154. Gustave Doré’s extraordinary 1888 image of angelic support for Louis IX embarking on crusade in 1248.

155. The headline of L’Epoque, 10 June 1945, reads ‘France will not renounce its thousand-year influence in the states of the Levant’.

A distinct German tradition in many ways paralleled the French. A definitive German crusades narrative had been provided by Friedrich Wilken (1777–1840), Geschichte des Kreuzzüge nach morgenländische und abendländische Berichten (A History of the Crusade from Eastern and Western Sources, 7 volumes, 1807–32). Wilken’s history, as its title indicated, rested on Arabic as well as western sources, lending his account a neutral air, far removed from Michaud’s triumphalist clash of civilisations. However, Wilken’s survey implicitly subscribed to the positive materialist interpretation, sustained by the inclusion of the Baltic crusades to which his employer, the kingdom of Prussia, owed its existence. This allowed his history to be mined for a positive German legacy which, in extreme form, became almost as anachronistically nationalist as its French equivalent, the crusading feats of Frederick Barbarossa being harnessed in the creation of a mythic national hero. The crusades were respectably integrated into a German narrative of development, ‘an agitation favourable to liberty and progress’. This fitted a wider project of identifying a unifying German spirit in medieval sources, demonstrated in the editing of specifically German texts under the auspices of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (founded in 1818–19).

In parallel, the German academic tradition transformed study of the crusades through forensic critical study of sources (Quellenkritik) pioneered by Leopold von Ranke. Building on one of Ranke’s insights, his pupil Heinrich von Sybel (1817–95) in his Geschichte des ersten Kreuzzüges (History of the First Crusade, 1841) placed crusade scholarship on a wholly new footing in using textual analysis to challenge the primacy of the account of the First Crusade by William of Tyre that had largely held sway since the thirteenth century. Von Sybel saw that no text could be taken at face value without interrogating its sources, origins and context. In the process he demolished the intellectual credentials of almost all previous supposed experts on the crusades, being notably harsh on Michaud. Yet while ostensibly setting the crusades free from uncritical histories ‘of a purely national or patriotic tendency’, von Sybel’s work did not release the subject from nationalist appropriation.10 The identification of a distinctive German dimension within a scheme that saw the crusades as furthering cultural progress towards a destined national unification was not politically neutral. While von Sybel’s work led to the forensic scrutiny of texts, it also cast a legitimising penumbra around wilder nationalist fancies, such as state-sponsored attempts to unearth Barbarossa’s remains in Tyre or the excesses of Wilhelm II’s much -publicised visit to Palestine and Syria in 1898 during which he essayed the remarkable trick of posing both as a neo-crusader and as an admirer of Saladin. Study of the Baltic crusades and the Teutonic Knights sharpened awareness of the roots of German cultural and political imperialism. This fed a strand of aggressive German nationalism that found its most grotesque manifestation in Heinrich Himmler’s promotion of SS admiration for the Teutonic Knights. A more positive consequence saw the lengthy nineteenth-century restoration of the former Teutonic Knights’ castle at Marienburg/Marlbork. The fate of the other great Teutonic Knights’ castle, at Königsberg/Kaliningrad, capital of the Teutonic Order and later of East Prussia, confirmed the powerful symbolism of crusade history. In 1968 the castle ruins, which had survived bombardment by the RAF and the Russians in the Second World War and were now in the centre of Russian Kaliningrad, were blown up on the orders of the Russian leader Leonid Brezhnev.

156. The ruins of Königsberg Castle, 1944.

Of greater public impact than scholarship were the recreations of crusades and crusaders provided by a former pupil of William Robertson, the Scottish novelist Walter Scott (1771–1832). In the early nineteenth century, anglophone responses to the world of the crusades were couched in terms of the Protestant scepticism of Fuller, the Enlightenment disdain of Gibbon, and the insular view popular since the beginning of the seventeenth century that the crusades, in the guise of Richard I, represented a diversion from the national mission of reconciling Normans and Saxons to create the united world power of Scott’s day. In Scott’s novels Ivanhoe (1819) and The Betrothed (1825) the crusades provide a distant backdrop for the action while The Talisman (1825) is set in Palestine during the Third Crusade and Count Robert of Paris (1831) at the Byzantine court during the passage of the First Crusade. Scott’s crusaders were pre-Michaud and Wilken, more Tasso than Fuller. While the focus of each is on adventure, character, plot and, in the last two, extravagant romantic fantasy, Scott’s verdict on the crusades is clearly expressed in his essay on chivalry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1818 edition). The enterprise was flawed, an expensive, futile, if individually heroic, distraction. While encouraging noble deeds, the worth of Scott’s crusades may be assessed in the stiff-necked and morally compromised villains of Ivanhoe and The Talisman, the Templars. Unlike Michaud, Scott avoids demonising Muslims (or Jews); Saladin is the moral exemplar in The Talisman. Scott’s historical fiction became wildly popular across Europe, the vivid evocation of setting and character, despite the unreal plots, providing a sort of alternative history, one that inspired artists and musicians even more than Michaud did.

Scott’s view that the crusades were not admirable, while crusaders often were, influenced a whole non-Roman Catholic tradition. The emphasis on crusaders’ devotion, tenacity and self-sacrifice allowed the crusades to be seen as totems for both neo-colonialists and political reactionaries, nervous about the social and economic forces unleashed by early industrialisation. The crusades occupied a conspicuous place in the nineteenth-century cult of medievalism that emphasised religion, social hierarchy and moral discipline, cherishing an essentially aristocratic and rural lost world in contrast to the commercial, increasingly urban and socially mobile, disruptive realities of the early nineteenth century. Medievalism’s glamorous escapism provided a canvas on which reactionaries and reformers alike could sketch their critiques of the moral and social ills of the new industrial world: the political reactionary’s selfless idealist knight errant, the social reformer’s honest artisan or worker in touch with the process and fruits of production. Escapism it remained. Despite being presented as precursors of colonial expansion, such as the French conquest of Algeria after 1830, there were no serious attempts to revive actual crusades, a few eccentric dreams apart. Even the Hospitallers, exiled from Malta in 1798, abandoned any military role once they were established in Rome after 1834. The crusade’s appeal as a symbol of nostalgia in the face of the perceived mercenary tawdriness of material progress attracted romantic reactionaries and social critics, like the young Benjamin Disraeli in Tancred: The New Crusader (1847), who affected to be both.11 For the actual or parvenu aristocrat, the crusades also paid snobbish dividends: to boast a crusading ancestor – real or invented – conferred an aura of distinction both in fiction and in certain social circles into the modern era.12 For most, the crusades became entertainment, the vogue for medievalism securing their recognition in theatrical re-enactments, operas, paintings and popular novels. Impressionist images, not details, of the crusades remained embedded in popular culture across Europe. Even John Wisden reached for a list of the eight main eastern crusades to pad out his first edition of the Cricketers’ Almanack of 1864. Such cultural penetration was underpinned by continued analogous use of crusading language in religious settings, such as Christian youth associations or Sabine Baring-Gould’s hymn Onward Christian Soldiers of 1865 (music by Arthur Sullivan, 1871; Sullivan also composed music for an opera based on Ivanhoe in 1891), and in secular application to vigorous campaigning, military or not.

157. J.A. Atkinson’s 1775–1831 depiction of the death of the Templar Brian de Bois-Gilbert in Ivanhoe.

Religion and War

The two elements that most characterised the crusades supplied the trickiest legacies: religion and war. While certain Roman Catholic devotees in Europe and the colonies sought and found inspiration in the crusades,13 for liberal, Protestant or secular nationalists, colonialists and imperialists the attraction lay in what they imagined the crusade taught of human endeavour, economic development and social progress. Although obviously seen as anti-Islamic, the crusades tended to be placed by nineteenth- and twentieth-century observers in a cultural not religious context. Specifically religious aspects could be rendered secular – the desire to conquer the Holy Places becoming a form of early colonialism, or merely eccentrically archaic and baffling – such as pilgrimages and relics. Religion cut across nineteenth-century nationalism and vice versa. In the new, religiously divided nation of Belgium, created in 1830, Godfrey de Bouillon could only act as a national symbol, and his statue placed in the Grand Place in Brussels in 1851, by ignoring the religious specifics of his crusading. The emphasis fell on crusaders’ ‘spirit’, not their spirituality. Crusading also provided rhetorical cover for racist imperialism: the Belgian conquest and exploitation of central Africa was described as a crusade by its instigators.

158. Statue of Godfrey of Bouillon, Brussels.

The violence of crusader warfare was discreetly transmuted into adventure stories of heroism and suffering, with little empathy for the victims, similar to how colonial wars were reported in home countries. When war came to western Europe, crusade analogies were paraded but soon exposed as threadbare. During the Crimean War (1854–6), fought in part over control of the Holy Places, crusader parallels fell foul of the inconvenience that the western ‘crusading’ powers were in alliance with the Ottomans against Christian Russians. Both the First and Second World Wars drew excited comparisons with crusades, as sacred national causes, or contests with barbarians, generalised right versus specific, secular evil (as in Dwight D. Eisenhower’s war memoirs, Crusade in Europe), not as specifically religious conflicts even if God was an early recruit. The chivalric overtones in sentimental enthusiasm for the First World War choked in the blood and mud of Flanders and Gallipoli. The only modern war that adopted the crusade as a clear religious parallel was General Franco’s revolt and successful civil war in Spain (1936–9), which to the Fascists was a cruzada española. By comparison, the use of the crusade as a motif by Franco’s republican and communists opponents, ‘crusaders for freedom’, while ideological, was wholly secular, a crusade by literary analogy not emotional emulation. In the 1960s, faced with the neo-crusading ideology of South American Liberation theology that urged the faithful to fight social and political oppression as a religious duty, the Roman Catholic church hierarchy declined to endorse it, and not just because it was often in cahoots with the repressive regimes that Liberation Theology was designed to challenge. To those historically alert, the notion of holy war no longer appeared attractive.

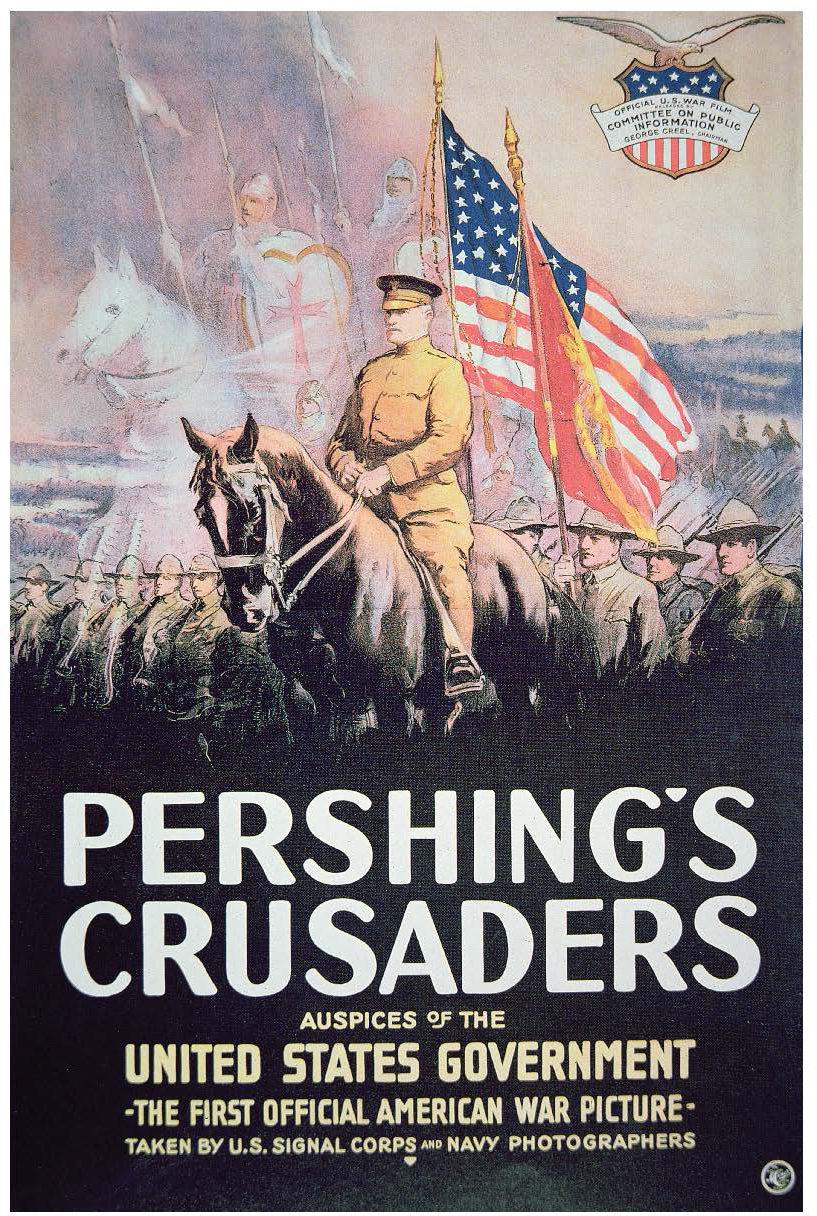

159. Continuing parallels: ‘Pershings Crusaders’, a poster for an official US First World War film.

New Lamps for Old

With the withdrawal from empire after 1945, French politicised academic interest in the crusades slackened, and the French model of an integrated Outremer society was systematically dismantled, contradicted by the primary evidence of a social structure harshly stratified on religious, racial and cultural grounds, and by closer scrutiny of other theatres of crusading and the crusaders’ own inspirations. Yet critics of the French model were no less politically engaged. The Israeli historian Joshua Prawer (1917–90), the leading post-1945 scholar of Outremer, in pointedly describing society in the kingdom of Jerusalem as characterised by a system of ‘apartheid’, was keen to establish how the Zionist settlement in Israel differed fundamentally from that of the crusaders in depth and permanence of occupation, while also asserting the impossibility of social and cultural merging of settler and indigenous communities. Prawer’s crusaders became part of continuing debates over the nature of modern Zionism.14 More broadly, the mid-twentieth-century intellectual as well as political retreat from western imperialism changed how historians examined the nature of the crusaders’ conquests and their cultural and economic impact, in the Levant and in the Baltic, eroding the idea of the crusades as instrumental in a ‘rise of Europe’.

If changing geopolitics refocused views on the material consequences of the crusades, they also stimulated a renewed interest in their ideology. In 1935, Carl Erdmann (1989–1945), a German scholar of medieval political ideas and an expert on eleventh-century papal correspondence, published Die Entstehung des Kreuzzugsgedankens (The Origins of the Idea of Crusading), the single most original monograph on the crusades in the twentieth century. This tackled the central issue of the alliance of religion with war and the background to its application by Urban II. The crusades are placed in the long perspective of Christian acceptance of the military values of the ruling elites. Erdmann’s exploration of the parallel impulses of official church policy and popular knightly mores set the crusades firmly within the general orbit of European culture. By exploring the pathology of early medieval Church-sanctioned public violence, Erdmann, while far from offering a direct critique of the militarism of German National Socialism, addressed a subject of obvious contemporary and not just German relevance: the communal mobilisation of violence in support of ideologies, religious or secular. His unsentimental approach to church history and ecclesiastical leaders was matched by coolness towards the whole concept of holy war and crusading, more informed by the experience of the popular militarism of the Second Reich before the First World War than the immediate challenge of the Nazis. Erdmann took the intellectual and psychological forces behind crusade ideology seriously on their own terms not as a disguise for something else – fanaticism, adventurism, greed, hysteria or escapism. In rejecting the crude material and economic reductionism of the previous Franco-German model, Erdmann restored the crusades as an aspect of internal European culture and as a religious enterprise.

Erdmann was not alone in rebalancing of crusader studies in sympathy with the twentieth-century experience of ideological conflict and popular political movements. However, some historians still clung to the old idea that religion was a cover, one prominent American crusade expert suggesting that to argue for the religious cause of the crusade was ‘like accepting the statements of Pravda that the USSR is only altruistically interested in establishing “truly democratic peoples’ governments”’.15 This was written in 1948, in the early years of the Cold War. However, other scholars in the 1930s and 1940s, especially in France, followed the same path as Erdmann, studying crusading mentalities, rhetoric, liturgy, art, canon law, popular religion, mass psychology and the means of transmitting church doctrine to the laity.16 This tradition of treating the religious motivations of lay crusaders seriously and framing the crusade within medieval developments in doctrine and canon law underpinned much of the anglophone recrudescence of crusade scholarship in the later twentieth century. This religious turn co-incided with similar approaches adopted by scholars of Arabic and Hebrew sources, shadowed by the rise of new militant Islamism in the Near East and the Christian religious Right in the United States, Europe and Russia.

Twentieth-century academic reassessment of the crusades may have suited the times, but it exerted limited public impact. The popular image of the crusade, in the west as across Islamic Asia and Africa, remained stubbornly traditional: undefined fanaticism, avaricious motives, brutal and mercenary conquests. The whole enterprise was assigned to an inferior past world of irrationality, almost in disregard of the brutality of the twentieth century. The crusaders still stood, as they did for Walter Scott, as energetic barbarians blundering with varying degrees of sincerity into the sophisticated Orient (itself a crude unhistorical Orientalist construct), a brute example of culture wars. This view received apparently scholarly affirmation in Steven Runciman’s History of the Crusades (1951–4), by far the most read and socially cited work on the crusades of the twentieth century, the most popular study since Michaud’s Histoire with which it shares not a few characteristics: moral certainty, literary imagination and historical invention.

Runciman, a Byzantinist and scholar of the medieval Balkans, relied heavily for his epic narrative on secondary sources for his factual structure, ideas and details, especially French scholarship of the 1920s and 1930s, to which he added an inimitable stylish gloss. He expanded the traditionally hostile view of the crusaders as barbaric disrupters of the sophisticated Muslim Levant to include Byzantium, promoting the crusades as a central feature of Byzantine history. By undermining the eastern Christian empire, the crusaders’ misplaced zeal betrayed the allies they had initially come to assist and so – in terms familiar to previous writers as far back as Knolles and Fuller – allowed the Ottoman conquest of eastern Europe, a circumstance Runciman instinctively assumed to be deplorable. However, Runciman reached beyond the crusades in a threnody for a lost world of reason, twentieth century no less than medieval. The crusades bore witness to the eternal dangers of unbridled ideological passion pitted against civility. This was not an attack on religion but on cultural philistines, demagogues and self-righteous, intolerant followers of totalitarian systems of belief, religious or secular – by implication nationalism, communism, fascism or capitalism. Like Gibbon, he lamented the damage caused by untempered enthusiasm. Like Walter Scott, whose novelist’s skill he shared in creating believable scenes of action, Runciman saw little admirable in the crusades except individual courage and endeavour. From a vertiginous pose of confident intellectual eminence, Runciman passed timeless adamantine judgements, none more so than his famous condemnation of the crusaders’ sack of Constantinople in 1204: ‘there never was a greater crime against humanity than the Fourth Crusade’, a verdict delivered in 1954, just years after the principle of crimes against humanity had first been defined and internationally accepted in the aftermath of the atrocities of the Third Reich, Japanese imperialism, the Holocaust and the Second World War. The immediate contemporary resonance was deliberate: in Runciman’s memoirs of 1991, ‘crime’ had changed to ‘tragedy’.17

Modern Politics

Runciman’s History of the Crusades sustained a familiar attitude to the crusades (and the Middle Ages in general) as irrational and materialist, destroyers of the superior and peaceful worlds of Byantium and Islam, impressive but essentially shameful. While this opinion may be of only cocktail-party interest in western countries, it becomes more significant when exported to the political arena. Modern responses to the crusades can retain a presentist political tinge, implied or deliberate. In First World discussion, while the neo-colonial view still persists, the rise of Christian fundamentalism of various hues has encouraged a rejection of the materialist interpretation of crusader aggression and Muslim victimhood in favour of an insistence that the crusades were a legitimate defence against Islamic invasions, even part of a supposed age-old clash of civilisations. Such a Manichean view is mirrored in parts of the Islamic world. General cultural responses to the crusades which, over the centuries, have proved as local, varied, complicated and shifting as those in the west, have been lent a sharp modern edge through propagandist exploitation by two distinct Near Eastern groups: secularist regimes eager to wrap themselves in the legitimising robe of pan-Arab champions (Saladin was a public hero alike for Presidents Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt, Saddam Hussein of Iraq and Hafez al-Assad of Syria); and their domestic, especially Islamist opponents (such as the Muslim Brotherhood or al-Qaeda), who use the continued western incursions into the region as standing condemnation of the existing status quo.

160. Saladin as modern Arab hero: President Hafez al-Assad’s statue of him in Damascus.

This use of the memory of the crusades to assert Muslim unity and identity, while offering a critique of existing rulers, echoes some of the oldest traditions of Near Eastern reactions to the historical crusades. Each generation writes its own version of the crusades to suit contemporary interests. As in the west, there has never been a uniform ‘Muslim’ view of the crusades. Historically, Near Eastern Muslim responses have displayed flexibility on a spectrum including twelfth-century Palestinian, Syrian and Lebanese refugees; time-serving jihad-promoting apologists of Zengid, Ayyubid or Mamluk rulers; critics of supposedly supine Islamic governments; promoters of ideal Koranic rule; and writers who regarded the Franks as little different to other invaders of the dar al-Islam and who expressed little concern, especially after the final expulsion of the Franks from the Levant mainland in 1291. These diverse views were held concurrently as well as sequentially, with perspectives inevitably differing in Iraq, Syria or Egypt. Whilst heroes such as Nur al-Din, Saladin and Baibars entered street folklore across the eastern Mediterranean into the early modern period and beyond, the ultimate victory over the crusaders, the long rule of the Mamluks and Ottomans, and the absence of aggressive western intervention in the region until Napoleon in 1798–9, consigned the crusades to popular memory and antiquarian footnote. Until the late nineteenth century, there was not even a specific Arabic word for the crusades. Even then, the need for one (e.g. al-hurūb al-Şalibiyya, the cross wars, or harb al-Şalib, the war of the cross) was generated by Ottoman and Egyptian writers drawing parallels between current western European colonialism and the crusades. Ironically, the idea of the crusades as a colonial adventure was encouraged by a direct import from the west, for example the translation of Michaud’s Histoire des croisades into Turkish (1866–7). Thus the west’s own vulgar politicisation of the crusades spawned a toxic legacy made more virulent with the shameless French assertion of historic claims to mandates in Syria and Lebanon at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.

161. Saladin enters Jerusalem in 1187: a modern Egyptian image.

As a strand in modern polemic, the crusades possess obvious attractions for those in the Near East wishing to portray themselves as victims of western aggression. Hence the dismay in Europe (although not so obviously in the United States) at George W. Bush’s ill-judged use of the term in describing his ‘war on terror’ as ‘this crusade’ (17 September 2001), shortly after 9/11. The crusades and hostility to the State of Israel, with its apparent geographic and demographic parallels with the European settlement of the medieval kingdom of Jerusalem, have been harnessed by groups such as al-Qaeda, the Muslim Brotherhood and ISIS in the shorthand of ‘crusaders and Zionists’, a historical oxymoron. Yet studies of how the crusades are portrayed in school textbooks suggest subtler distinctions, with a range of attitudes from balanced historicism (e.g. in Lebanon) to Manichean confrontation and Muslim supremacism (e.g. in Egypt and Saudi Arabia). With Israelis also reassessing attitudes to the crusading Franks in the context of inherited space and shared antagonists, across the region images of the crusades continue to resonate and divide, even as Arabic scholarship establishes distinctive academic credentials.18 Western historians’ focus on the crusades’ origins, ideals, motives and organisation scarcely helps to obscure the perception of the political and territorial reality of the original invasion of the eastern Mediterranean.

The Near East is not the only crusade frontier of contested memories. The Spanish crusades had been folded into the reconquista mythology of national identity and power, a vibrant symbol of the union of Church and State that long excluded the past dispossessed (Jews and Moriscos) and modern dissidents (socialists and democrats), especially under the Franco regime. In the Baltic the legacy was harder to accommodate. The Teutonic Knights had created Prussia, until its abolition in 1945 a major cultural as well as political constituent of German nationalism. In 1701, Frederick I, the first king of Prussia, was crowned at the Teutonic Knights’ Königsberg Castle. Further east, in the less Germanised former Teutonic Knights’ state of Livonia (Latvia and Estonia), shifting political regimes – German, Swedish, Russian – determined how the crusaders were perceived: civilising Christian liberators or confiscating tyrannical invaders who destroyed the primary freedoms and culture of the indigenous people. The interpretation of the crusades played out between alternate sympathy for the Germans as modernisers, Russians as allies against the German yoke, or a nascent local nationalism. Since the end of the Cold War, Scandinavian and Baltic medievalists have sought to escape these stereotypes, looking towards links with Europe beyond the awkward Russo-German duopoly.19 The crusades have provided a means to achieve this, by associating the far north with developments and policies derived from and pursued by interests at the heart of medieval European Christendom, in its way a mirror to the region’s increasing ties with the rest of Europe through NATO and the European Union. However, this approach in turn runs the risk of concentrating on the dynamic of invasion (which is where the written sources come from) in a teleology of conquest and integration. Recent archaeology has raised questions of the nature, wealth and complexity of the silent conquered communities, research that accidentally or not accords with the post-Cold War and newly independent eastern Baltic. Thus in Estonia as in Egypt and across the globe, the crusades, as for centuries past, remain contemporary.