Chapter 1

Warfare, Violence and Society

Why Go to War?

Imagine you are a thegn living on a modest estate somewhere in the south of England. It is the middle of the tenth century and there is trouble everywhere. Your lord lives within riding distance and one morning you receive a visit from his messenger. You are told to get ready for war. What is it that would compel you to go?

According to modern anthropological research there were a number of reasons for conflict and aggression in the Anglo-Saxon era. In a widely cited paper that concentrates on this subject in respect of the earlier Anglo-Saxon period (600–850), Guy Halsall has elucidated motives such as personal grievances, insults and justifiable revenge as reasons for aggression during this earlier period. All of these motives are evidenced in the Anglo-Saxons’ texts themselves. It is argued that in the pre-Viking period in England there is a heavy ritualistic taint to the aggression between kingdoms.

One of the mechanisms that drove all this stayed with the Anglo-Saxons right up to 1066. There was a compelling need in Germanic communities for young men to prove themselves as warriors. It was a vital part of their coming of age. Warfare played a central role in the making of a warrior leader and the subsequent impression he made on his followers. The accrual of riches and gifts with which he could attract a larger retinue and spread the power of his kin group was driven by his prowess on and around the battlefield. Old English literature is packed with references to warfare as a way of life in this respect. For example, there is evidence in the Maxims and in The Battle of Brunanburh poems to show the symbolic value of gift giving and ring giving, of the protection of warriors and of daring weapon play in battle. Maxims, for example, has the following passage:

A wound must be wound, a hard man avenged. A bow must have an arrow, and both together must have a man to accompany them. Treasure rewards another; a man must give gold. God may give riches to owners and take them away afterwards. A hall must stand, and grow old.

The Battle of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle mentions the role of the king as ring-giver:

Here, King Athelstan, leader of warriors,

ring-giver of men, and also his brother,

the ætheling Edmund, struck life-long glory

in strife round Brunanburh, clove the shield-wall,

hacked the war-lime, with hammers’ leavings . . .

The notions of the giving and receiving of gifts, of vengeance for the death of one’s lord and of the desire to win glory in battle are never far from the surface in Anglo-Saxon literature. It was an ideal, as we shall see, that had practical benefits if a lord was to surround himself with the right men for the job. It is argued that the lordship ties that bound a man to his lord were just as important to an Anglo-Saxon at the time of Hastings (1066) as they were before the dawn of the Viking invasions of the ninth century. It is accepted that by this time there was a sense of archaism to all this–a reference perhaps to an age long gone, but in any ideal there is always some form of reality.

The need to prove oneself, to find a lord to serve was a driving force behind the martial activities of young men, but the Scandinavian invasions of the ninth century made the need for men to protect their estates that much more urgent. So, what became the chief reasons for warfare in the subsequent centuries leading up to the Norman Conquest? Where exactly was the threat? The picture is obscured by the question of interpretation. One man’s boundary dispute is another man’s defence of the realm, so to speak. If we take just the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle as a bench mark, some broad conclusions can be drawn. Wars in the Viking period (that is, after 865) in England were fought by the Anglo-Saxons as part of a ruler’s protection or expansion of his kingdom or other patrimony. The leader had to fight such actions or risk losing the men he had attracted to his household. It was a cyclic thing that meant that warfare was virtually endemic on a number of levels, the key to it being the need for a king to attract and reward men to his calling and then for him to have to expand his wealth to accrue more gifts and riches with which to reward them. For this he needed a bigger army, and so it goes on. The story is the same for the different levels of the aristocracy. When the ealdormen and thegns of Anglo-Saxon England came to loggerheads over competing interests the result might be homicide and this was followed by a subsequent and very damaging ‘feud’ between rival families (see pp. 21–3).

The consequences of the loss of manpower through military ill preparedness were felt by Alfred the Great (871–900) in the early years of his reign. A mixture of treachery and poor strategy saw the invading Danish army all but divide and conquer Wessex in the 870s. For a brief time Alfred became an exile within his own kingdom. The way in which he fought back by re-organising his kingdom’s fighting resources and accruing wealth and loyalty through re-conquest is testimony to the success of the Anglo-Saxon warfare model. The warfare dynamic needed constant feeding from the ranks of freemen who had the right to bear arms. It is no surprise then that during the reigns of rather more peaceful kings, the system would creak a little under the weight of disaffected magnates whose rewards were not as great as they had been in times of cyclic warfare.

There was another driving force behind the reasons for going to war in the Anglo-Saxon period and this was the ‘feud’, the mechanics of which are examined more closely below (see pp. 21–3). The feud counts as a step up from the simple brawl. It has more to do with cycles of vengeance among rival groups usually connected by kinship ties. The trigger was usually a murder. Curiously, the competing factions of extended kin groups fought each other throughout the Anglo-Saxon period regardless of the Scandinavian influx. In fact, the phenomenon became a feature of northern Anglo-Danish life just as much as it was in the southern Anglo-Saxon world, leading eventually to some urgent legislation on the subject brought about by a concerned King Edmund I (939–46).

The Anglo-Saxon response to the keeping of law and order throughout these centuries is worthy of a volume in its own right, but suffice it to say that the Hundred Courts (or Wapentakes in the areas of Danish influence) were attended by men armed and prepared for action in whatever form it took. There was much concern with the economic impact of cattle rustling throughout this period and cross-border theft and large-scale raiding was a reality that often produced a military style response. Similarly, there is a militaristic tone to the London Peace Guild of the reign of King Athelstan (924–39). This law code, known as VI Athelstan, provided for the division of freemen into groups of nine with one leader, each known as tithings, their role to pursue criminals. We might imagine the men of London in their mounted posses chasing down robbers and those who housed them across the countryside. But whether this was warfare or a form of ‘policing’ is a moot point.

The economics of warfare were not lost on the protagonists of the period. Many battles during this period were fought near ports. The first Viking invaders often targeted the low-lying trading settlements on the English and French coasts where merchants plied their trade from vessels and stalls almost on the very shore line. Portable wealth was never far from the mind of any war leader in Anglo-Saxon England. The great Welsh leader Hywel Dda (b. 880, d. 950) made no secret of the fact that cattle raiding and other forms of portable wealth formed part of his foreign policy of the day. Clearly, it was in the interest of the king to protect such places from harm and from Athelstan’s time there were even royal ordinances actively to promote trade in such centres.

But if we look at it from the point of the warrior himself, from the point of view of the man who found himself woken one morning by a messenger from his lord who told him of a hungry and merciless enemy marching to the borders of his lord’s kingdom, or heading for the royal estate nearby where the king’s winter food supplies and many other riches lay, we will know just one thing. That thegn went to war that morning because he owed that service to his lord. The fact that our thegn held his estate in return for military service meant he was sometimes called upon to provide it. Indeed, his lord may have given him arms and armour when he took him into his household for this very purpose. And on this particular hypothetical morning, with a threat apparent to the wealth and prestige of his lord’s lord (the king), the thegn knew he had to respond. His lord had told him to get ready. His lord had told him who else to bring, how to provision himself and where to meet. The war had begun.

Where Were Wars Fought?

It is not often that a military encounter took place during the Anglo-Saxon period without there being a practical military consideration for the choice of location. According to Guy Halsall, between 600 and 850 it is apparent that excluding civil wars and early Viking attacks, there were twenty-eight battles fought between antagonists. There is evidence to suggest that many of these battles took place at river crossings or near to ancient monuments. The river crossing locations can be explained militarily. Fords and bridges have always had a vital strategic significance and it should be no surprise that campaigners in the Dark Ages chose to meet enemies at these nodal points on the route ways into each other’s territories. A glance at a list of early battles from the Anglo-Saxon period will serve to illustrate the importance of river crossings: there were battles at Crecganford (485); Cerdicesford (519); and Biedcanford (571) to name just a few. The assertion that early battles were fought at ancient monument sites is a little more problematic for the later period, although they do seem to play a part not so much in the location of a battle site, but in being the key points for constituent parts of armies to gather.

For the period covered by this book there seems to be a number of different dynamics at work regarding the location of battles. While fords and bridges still feature heavily, there is a noticeable shift towards the importance of centres of economic wealth. Also, the part played by fortifications in military encounters between protagonists becomes crucial, as is shown by the figures in Table 1. Battles in open country do, however, still feature highly.

The list in Table 1 is based on an analysis of battles, sieges and raids mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and a number of other sources referring to the years between 800 and 1066. It only includes those military encounters where some sort of clear conclusion as to location can be made. It is not strictly scientific as sometimes there is only have a brief mention of a fortified location but it cannot be said for certain that a recorded nearby pitched battle may have been the relieving of a siege, for example. Not included in the table are the numerous examples of regional devastation–the deliberate reduction of a landscape–carried out by settled Danes or by the Anglo-Saxon king himself. These do not amount to battles, sieges or raids as such, but were a completely different type of military strategy (see pp. 77–9). It should also be borne in mind that the references to battles in ‘Downland/Open Country’ were in reality never far from communications networks, such as roads and track ways that played a key part in the transportation of armies of the period.

Table 1. Where were battles fought (800–1066)?

| Pitched Battles | |

|---|---|

| Ford or Bridge | 6 |

| Downland/Open Country | 16 |

| Pre-arranged Field | 1 |

| At River Estuary | 2 |

| Coastal Royal Estate or Mint | 4 |

| Inland Royal Estate/Manor | 5 |

| Coastal Ancient Hillfort | 1 |

| At or Near to Inland Ancient Hillfort | 1 |

| At or Outside a Port | 2 |

| At Anchorage/Moorings | 2 |

| At or Outside a Defended or Fortified Place | 12 |

| Attack upon a Royal Capital/Citadel | 4 |

| Sieges | |

| At Viking Purpose-built/Modified Fortifications | 11 |

| At Anglo-Saxon Fortifications | 8 |

| At an Island in a River | 1 |

| At a Port | 3 |

| Viking Raids | |

| Port | 13 |

| Devastation | 7 |

But if we are hampered by the question of interpretation, there are still some interesting conclusions to be drawn from the exercise. There should be no surprise at the fact that the Viking raiders chose ports so often, as these were places that were packed with riches, as indeed were the monasteries. But when the Danes were an actual army on active operations within the Anglo-Saxon kingdom, things were somewhat different. Apart from the ‘Downland/Open Country’ category, which we might expect to rank highly, the presence of fortified places and royal centres hints at a game of strategy in the landscape. It is also clear that the Anglo-Saxons besieged the Danes more often than the Danes besieged the Anglo-Saxons. This change in the nature of the locations of battles came about after the Danes had become settled in the Danelaw at the end of the ninth century. Both they and the Anglo-Saxons operated from strategically located fortified bases and for the first few decades of the tenth century warfare became a matter of political geography with the fortification programmes of Edward the Elder (900–24) and his Mercian sister Æthelflæd playing a vital role in combating the Danes in the midlands.

What is missing from the list in Table 1 which was there for the earlier period is the mention of ancient monuments. We know that these places were important. It is certainly the case that there were more prehistoric remains littering the Anglo-Saxon landscape than there are today, but what sort of impact may these places have had on the psyche of the Old English people and how did this translate into the considerations of an Anglo-Saxon general on campaign?

The Old English people revered the ancient landscape around them. The poem The Ruin seems to celebrate the glory of Roman Bath and Maxims II refers to ancient stone fortresses as ‘the work of giants’. Neolithic burial chambers were given names conjuring up images of the English people’s pagan past, such as Wayland’s Smithy in Berkshire. Here, at the site of a long barrow swathed in mystery, was a place where English folklore suggested passing travellers would have their mounts shoed by Wayland the Smith. It is possible that English armies were summoned to these types of places as gathering points for a campaign. Alfred the Great (871–900) did it at Egbert’s Stone in 878, bringing together a large host of men from the remaining shires that still owed him allegiance. Later, in 1006 at the height of King Æthelred II’s (979–1016) troubles with the Danes, the enemy army camped at Cwichelmslow, Ashdown (Berkshire), the site of another ancient barrow. This site was chosen by the Danes after they had raided their way through Hampshire and Berkshire on a destructive mid-winter campaign, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle telling us they ‘ignited their beacons as they travelled’. Cwicchelmes Hlæw (meaning the ‘Hill of Cwichelm’), now known as Cuckhamsley Knob, is on the ridgeway at East Hendred Down in Oxfordshire. It is a place steeped in Old English history, purporting (wrongly) to be the site of the burial place of Cwichelm himself, a Dark Age Anglo-Saxon leader, but most importantly, it became the meeting point for the shire assembly right up until the seventeenth century.

The Danes of 1006, once in position at Cwichelmslow, are said by the chronicler to have ‘there awaited the boasted threats, because it had often been said that if they sought out Cwichelm’s barrow they would never get to the sea. They then turned homewards by another route.’ The choice of site is quite explicit. The Danes knew of the boast of the English. They knew also that this meeting place was a long-established focal point for the Anglo-Saxons and that it was an obvious place to try to bring battle. So, here in 1006 was a potential battle being brought about by a foreign invader whose strategy was to accommodate an ancient English tradition in the landscape. The ‘igniting of beacons’ reference may even have been a ridiculing of the Anglo-Saxon civil-defence system which itself relied upon beacon signals. It could be argued that the Vikings were in fact instigating their own signalling system (for which there seems to have been an historical precedent according to the chronicler) by using advanced parties to mark out the line of march for the main army. A fuller discussion of the use of beacons is included below.

It can be seen that there was a variety of locations for Anglo-Saxon battles. Centres of economic importance and communications networks feature highly, as do fortifications, but if the Cwichelmslow episode of 1006 shows anything it does at least demonstrate the continuing importance of the ancient monument in the increasingly sophisticated Anglo-Saxon military landscape.

The Training of the Anglo-Saxon Warrior

Little is known about what sort of military training an Anglo-Saxon warrior had before he set foot on the battlefield. We may suppose that it was not formal in the sense of regular soldiery. There is no evidence to suggest that the armies of later Anglo-Saxon England were paraded, drilled and marshalled quite like their Byzantine or Middle Eastern counterparts, but we must also accept that because warfare was a way of life for so many men in this era, there will have been a degree of formality behind the preparation of a young man for a life of military prowess.

Although it is a difficult area to find evidence for, it seems that the military tradition among Anglo-Saxon warriors in the early centuries began with the fostering of a young warrior in another man’s household. In the poem Beowulf, the eponymous hero himself went to Hrethel’s household when he was just 7 (lines 2,435–6).

Beowulf spoke, the son of Edgetheow:

‘In youth I many war-storms survived,

in battle-times; I remember all of that;

I was seven-winters (old) when me the lord of treasure,

the lord and friend of the folk, took from my father;

held and had me King Hrethel,

gave me treasure and feast . . .

This poem, written in the tenth century or later, is recalling a practice from the dawn of the Dark Ages, a pagan rite of passage still a familiar thing to the Christian readership for which the work was intended. The character Beowulf was not the only male figure from the Anglo-Saxon world to embark on a form of training-in-service. Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert describes his subject as entering a boy’s company in his eighth year, ‘the first year of boyhood succeeding from infancy’. Here he learned to exercise, wrestle jump and run. From the Life of St Guthlac and the Life of St Wilfred we gain evidence that the next stage of a boy’s training came at around 14 years of age. Guthlac is recorded as being part of a group of youths that engaged in all sorts of slaughter and pillage by the time he was 15. Wilfred at 14, just before he decided to enter a monastic life, was given arms and horses. Quite how the young Anglo-Saxon boy warrior, or as he is often termed in Anglo-Saxon literature, ‘geoguð’ (‘youth’), trained himself in the skill of weapon play is open to question. It was a long journey for a 14-year-old boy to become a duguð, a fully fledged warrior.

What sort of skills were imbued in the early Anglo-Saxon warrior by the men of his chosen household can only be guessed at. The main weapons of the day included the spear, the sword, the throwing axe and javelins and to a lesser extent the bow. Each of these requires a degree of skill to wield effectively. It may be that mocked-up weapons were used by the young warriors for their training, but evidence is very poor in this respect. We are also badly off for written evidence of how weapon play may have been taught, although the thirteenth-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus describes his hero Gram copying the intricate sword strokes of older men such as parrying and thrusting. Hunting may have played a role in the training of the youths, particularly the boar hunt which involved the use of dogs, nets and a spear with a hefty blade to penetrate the hide of the animal. The association of young men with ferocious animals across the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic worlds is well known and is evidenced in names such as Beorn (‘bear’). We might permit ourselves to imagine the constant honing of a young man’s hand-to-hand combat skills during these formative years. It was something we have evidence for among the later Saxon nobility. King Athelstan (924–39), according to William of Malmesbury, ‘clad in the flower of young manhood, practiced the pursuit of arms at his father’s orders’. It is a tantalising suggestion. We do not know who would have been appointed to do the training, but at this high social level, and considering that so much of the military and royal household organisation in tenth-century England was similar in nature to that of the Carolingian Franks, we might assume that the training of princes was a carefully organised matter.

There is some evidence that Anglo-Saxon ealdormen provided a degree of training to the men who followed them if we can believe the descriptions of Ealdorman Byrhtnoth in The Battle of Maldon. However, such descriptions have an ancestry in classical writings and may need to be taken with a pinch of salt. There is a passage in the poem that describes how the ealdorman taught, or at least reminded, his men of their training on the day:

Then Byrhtnoth began to array men there,

rode and gave counsel, taught warriors

how they must stand and that stead hold,

bade them their round-shields rightly hold

fast with hands, not at all frightened.

When he had fairly arrayed that folk,

he dismounted among them where it most pleased him,

where he knew his hearth-band most loyal.

It is an image of a commander giving hands-on instructions to his men, but it is unlikely that the thegns who followed the ealdorman were hearing it for the very first time. Byrhtnoth was giving them a reminder of the formations they had practised for years. He was steeling them for battle. We can find other examples of this sort of thing in other literary works of the period. Henry the Fowler (919–36), the Holy Roman Emperor, for example, performed a similar exhortation of his troops before the Battle of Riade in 933 against the Magyars, according to Liutprand of Cremona. Despite the obvious borrowing from antiquity, there may not be any good reason to doubt that the military leaders of the Anglo-Saxon era exhorted their troops on the battlefield.

Unfortunately, as is quite often the case with Anglo-Saxon evidence, there is little that quite matches the compelling evidence available for the Continental contemporaries, particularly that of the Carolingian Franks. Training for them is better evidenced in such forms as the Old Roman causa exercitii, a form of war game in which groups of mounted men charged at each other pretending to unleash their weapons and then retreating in a feigned flight. What little we have for the Anglo-Saxons, however, still shows us enough to conclude that an English warrior will have known how to use his weapons and where to put himself in the shield wall on the battlefield.

There is one interesting but rather late account of the Anglo-Saxon fyrd, or ‘host’, in training. It comes again from the quill of William of Malmesbury writing about the Norman King Henry I’s (1100–35) preparation for the invasion by his brother Robert, Duke of Normandy in 1101. He says that Henry ‘taught them how, in meeting the attack of the knights, to defend with their shields and return blows’. It is an ironic reference. If these men were English fyrdsmen, then it seems they were in the Norman period being prepared to face the onslaught of the mounted knight. One wonders if such training might have helped their forebears at Hastings.

Despite the training received by the Anglo-Saxons from a very young age, and despite the years of warlike preparation for the warrior of Anglo-Saxon England, it still remains the case that the consequences of going to war were profound on a number of levels. These included the personal injuries one might sustain and the political and personal consequences of exile or (and this seems to have been the most depressing of experiences) finding oneself without a lord. Death, of course, was always a possibility. The ways in which the Anglo-Saxons dealt with all these consequences of the violence of warfare are examined below.

Injury, Death and Exile–the Personal Impact of War

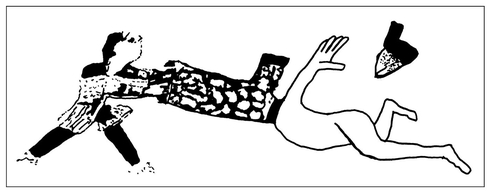

The images of the bodies of the dead depicted in the margins of the Bayeux Tapestry make for sobering viewing. Mailcoats are stripped from bodies, weapons collected and seemingly half-naked rotting corpses are left to lie on the battlefield. These indignities really did happen, such was the value of weapons and armour (Fig. 1). One is minded of the remark in The Carmen that bodies on the field of Hastings were left ‘to be eaten by worms and wolves, by birds and dogs’. A very grim and hardly chivalrous reality.

There are many literary references to the injuries inflicted by the weapons of the age on the bodies of victims. Not least of these is the fate of King Harold at the hands of a group of Norman knights at Hastings, described by the Norman sources such as The Carmen in gory detail. A piercing to the upper body with a spear, a de-capitation with a sword and the cleaving off of a leg tell of the end of a distinguished if bloody life. Indeed, some archaeological work has now shown that the physical effects of weapons in the Anglo-Saxon age were every bit as dramatic as the literary accounts would suggest. Analysis of bones on skeletal remains from a cemetery in Eccles in Kent dating from the Anglo-Saxon period has deduced not only the weapon types used against the victims, but also the nature of the injury as a whole, including its soft-tissue component. There were six male skeletons showing edged weapon injuries to the cranium, each was in his twenties or thirties. Not one of the injuries on these skeletons displayed any signs of healing and it is concluded that the cause of death must have been due to the traumas produced by the weapons. Profuse bleeding to the scalp and a loss of consciousness were factors in the death of the individuals with one victim (known as Victim II) suffering an immediate severing of the brainstem at the first strike. This same victim was also rendered incapable of defending himself (after clearly trying to) because injuries sustained to his arms prohibited him from gripping either a sword or a shield. Apart from one injury attributed to an axe, the blade of a sword or multiple swords is suggested as the chief weapon utilised upon the victims at Eccles, with Victim II receiving additional wounds in the back from a weapon unknown as he was lying prone. Many of the injuries, as one might expect, were to the left side of the cranium, delivered almost certainly by a right-handed opponent, with Victims I, V and VI exhibiting these injuries most clearly. It is evident from the recorded injuries to King Harold, and the examined injuries to the Eccles victims, and to the unfortunate headless Scandinavians whose grim end has been revealed by the trowel of the Oxford archaeologists on the ridgeway at Weymouth, that the body’s most vulnerable areas where there is little protection were the parts most often attacked by the deadly weapons of the day: arms, legs and, above all, the head. There is no doubt that the personal cost of warfare in the Anglo-Saxon period was one of very bloody consequence indeed. One is mindful of Edmund of East Anglia’s saintly demise–tied to a tree in 869 while shot full of Viking arrows. And also, the unfortunate Archbishop Ælfhere, whose ordeal as a hostage was ended with a brutal blow to the head from a drunken Dane in 1012 (pp. 32–3). The personal price was nearly always paid in blood.

Fig. 1. The robbing of the dead on the Bayeux Tapestry.

Another example of the brutality meted out to the victims of warfare comes from 1006 and Uhtred of Bamburh’s relief of a Scottish siege of Durham. The Scots’ heads were cut off and transported to Durham where they were washed by four women and placed on poles above the walls of the city. The women were paid one cow each for their trouble. Sometimes the fate of a victim of war was intertwined with the need to display the power of the victor.

But how did the Anglo-Saxons deal with their own war dead? The answer to this question probably lies in the rank and religion of those who fell. The poem Beowulf describes in great detail the funerary pyre lit for the eponymous hero, the construction of the mound in which he is buried and the great pagan ceremonies that went with it. All this seemingly fantastical imagery was brought into stark reality by the spectacular discovery of the Sutton Hoo treasures in 1939, but in the period we are now discussing, the English Christian armies disposed of their dead in a different way.

A good example of the lengths to which people went to bury their dead appropriately is that of Æthelwulf, the ealdorman of Berkshire, who on 31 December 870 had successfully defeated a detachment of the Danish Great Heathen Army at Englefield. Æthelwulf, a seemingly gifted warrior leader, lost his life only a few days after Englefield when he assisted the West Saxons in the disastrous siege of the Danes at their encampment at Reading. The chronicler Æthelweard records that when Æthelwulf’s body was finally recovered beneath the gates of the camp it was taken on a surprisingly long journey: ‘In fact, the body of the Dux mentioned above was carried away secretly and taken into Mercia to the place called Northworthig, but “Derby” in the Danish tongue.’ Æthelwulf, a Mercian, had died defending the northern frontier of Wessex and fighting alongside the West Saxons. Clearly, there were those in his retinue who could not forget the Mercian connection and who went to great lengths to see their leader buried in his proper ancestral place.

If there was a physical consequence to warfare–the shattered bones, the beheadings, the grim struggle at sword’s edge, then there was also an emotional side to the affair as well. There was nothing that so depressed the Anglo-Saxon mind as being forced into exile after a defeat. It might be that a warrior’s lord was lost in the struggle and he had failed to avenge his lord’s death on the battlefield thereby committing the sin of surviving the battle. To wander around in search of a lord was the Anglo-Saxon equivalent of purgatory, a condition that it seems threw some Anglo-Saxons into a melancholy of soul-searching. This is beautifully portrayed in the poem The Wanderer:

Often the solitary one

finds grace for himself

the mercy of the Lord,

Although he, sorry-hearted,

must for a long time

move by hand

along the waterways,

(along) the ice-cold sea,

tread the paths of exile.

Events always go as they must! . . .

The halls decay,

their lords lie

deprived of joy,

the whole troop has fallen,

the proud ones, by the wall.

War took off some,

carried them on their way,

one, the bird took off

across the deep sea,

one, the gray wolf

shared one with death,

one, the dreary-faced

man buried

in a grave.

The main character in The Wanderer loses his lord and wanders the landscape in search of a new hall, and a new gift-giver to serve. If this notion seems a little hackneyed or idealistic, it should be remembered that it crops up again in The Battle of Maldon, which was a real battle where the death of the ealdorman sparked a desire for vengeance in some of his followers.

The misery of exile was not just felt by the warrior who lost his lord, however. One rather sad example of this was the fate of King Burgred of Mercia (852–74). Burgred lost a war against the Great Heathen Army in 874. It was a strange war in that it involved no recorded fighting as such, but saw the Danes encamp themselves at the spiritual home of the ancient Mercian royal line at Repton. There the Danish leaders, having bled Burgred dry of money over the winter, were able to claim a legitimacy by burying their own dead at the resting place of a Mercian dynasty not of Burgred’s own line, but of that of St Wystan. In short, the Danes exposed Burgred’s own discomfort about his hold on the throne by establishing themselves at Repton. The impact of this psychological warfare was too much for Burgred. He took his wife and headed for Rome. They travelled through Pavia and finally arrived in the ancient city, where Burgred settled and later ended his days. He was not to be interred in a Mercian mausoleum as he might once have wished, but instead was laid to rest in St Mary’s Church in the English quarter of Rome.

There were many other examples of political exile and of death and great personal pain suffered throughout the period, but perhaps the last word should go to The Carmen, which tellingly describes a mother’s agony after the Battle of Hastings:

The corpses of the English, strewn upon the ground, he [Duke William] left to be devoured by worms and wolves, by birds and dogs. Harold’s dismembered body he gathered together, and wrapped what he had gathered in fine purple linen; and returning to his camp by the sea, he bore it with him, that he might carry out the customary funeral rites.

The mother of Harold, in the toils of overwhelming grief, sent even to the duke himself, asking with entreaties that he would restore to her, unhappy woman, a widow and bereft of three sons, the bones of one in place of the three; or if it pleased him, she would outweigh the body in pure gold . . .

Duke William of course, would have none of it, preferring to set up a pile of stones high upon a cliff at Hastings where Harold was to rest. One William Malet, half Norman and half English, took up the duty of constructing the macabre ‘tomb’:

and he [Malet] wrote as an epitaph:

‘by the Duke’s commands, O Harold, you rest here a king,

That you may still be guardian of the shore and the sea’.

Warfare, then, was a game of high stakes. The personal cost could be immense in terms of injury, death or exile and could even wipe out a whole dynasty in one encounter. When it came to competing families, the stakes were no less high. Let us look now at the curious phenomenon of the concept of vengeance to see where it fits into the picture of violence in the period.

Feuding

The words ‘feud’ or ‘blood feud’ are often applied to this period, having been borrowed from the High Middle Ages. In the latter period feuds were a state of lasting mutual hostility between family factions revolving around reciprocal violence. In the Anglo-Saxon period, however, ‘feuds’, which more properly should be called ‘cycles of vengeance’, were usually related to homicides and the need for retribution of the aggrieved. That is not to say there were not families strongly opposed to one another politically. Similarly, institutions could ‘feud’ with individual lords, such as monasteries pitting themselves against families who had a history of a controlling influence over them.

But it was the ‘cycles of vengeance’ that had far-reaching implications for the rulers of the day. Kings recognised the potential for a disastrous effect on the stability of the political landscape, a landscape that the king himself would have played a great part in creating. In his prologue to the law code concerning the problem, King Edmund I (939–46) decreed: ‘The illegal and manifold conflicts, which take place among us distress me and all of us greatly.’ What he went on to refer to was that vengeance for a homicide could only be carried out against the killer himself, to cease the practice of attacking the extended kin in retribution. The killer had a year to pay compensation. If an avenger carried out an attack against kinsmen instead, then he himself would become an outlaw:

- If henceforth anyone slay a man, he is himself to bear the feud, unless he can with the aid of his friends within twelve months pay the full wer [compensation], of whatever birth the slain man may be.

- 1.1. If, however, his kindred abandons him, and is not willing to pay compensation for him, then I wish that all his kindred be exempt from feud, except the actual offender, if they afterwards give him neither food nor protection.

- 1.2. If afterwards, however, any of his kinsmen harbours him, then–because they previously had abandoned him–the kinsman is to be liable to forfeit all that he owns to the king and to bear the feud as regards the kindred.

- 1.3. If, then, anyone of the other kindred takes vengeance on any man other than the actual perpetrator, he is to incur the hostility of the king and all his friends, and to forfeit all that he owns.

Vengeance killing, then, very much a part of Anglo-Saxon life, now had royal regulation. The law puts under royal management the whole notion of vengeance in a time that presumably had ample examples of all types of it.

Memories were slow to fade in Anglo-Saxon England. Families could have long-running disputes and people could harbour thoughts of vengeance for generations. One particular story from a twelfth-century Durham tradition brings the whole sordid issue to light in the grimmest of ways. Earl Uhtred, son of Earl Waltheof of Northumbria, had become very powerful under King Æthelred II (979–1016). When Uhtred married his second wife Sige, daughter of a man called Styr, some sort of arrangement seems to have been made whereby Uhtred would kill Styr’s enemy–a man known as Thurbrand.

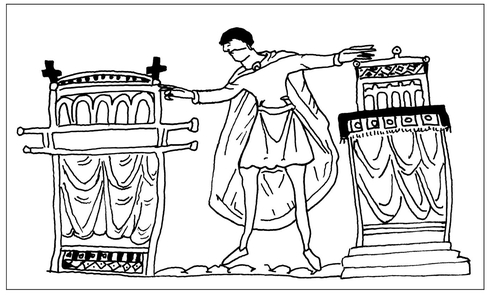

Nobody quite knows if Uhtred ever attempted it, but events would show that some very important people knew about the plot. This notwithstanding, Uhtred went on to marry another wife, the daughter of King Æthelred himself, and remained loyal to the king despite Cnut of Denmark angling for his service. Cnut, of course, went on to become king himself. He summoned Uhtred to his hall at a place called Wiheal and when Uhtred got there he was horribly deceived by one Thurbrand the Hold, probably our enemy of Styr. It was apparently at Thurbrand’s instigation that the king’s soldiers, who were hidden behind a curtain that stretched across the hall, suddenly sprang out from behind it and slaughtered the earl and forty of his men in what must have been an astonishing bloodbath.

Uhtred was succeeded by his brother Eadwulf, who soon died and was himself succeeded by Uhtred’s son from his first marriage, a man called Ealdred. Now the story–somewhat distorted through time–gets busy (as if it has not already been detailed enough). It was Ealdred who killed Thurbrand. Thurbrand’s son Carl sought out Ealdred, presumably for vengeance. In fact, the two of them tried to ambush each other from time to time until friends brought them around the table and brokered a peaceful settlement. It seems the two got along famously after this, even embarking for Rome together as sworn brothers, only to be thwarted by a storm at sea that caused them to return home. Carl received Ealdred into his home, bestowing the usual friendships on him and while honourably escorting him on his travels, he killed the unsuspecting Ealdred at a place called Risewood. A good example, perhaps, of keeping your enemies closer than your friends. Thirty-five years passed. A new player was on the stage. He was Earl Waltheof, grandson of Ealdred. He sent a band of warriors to Carl’s brother’s house at Settrington, near York. They caught the feasting sons and grandsons of Carl by surprise and slaughtered almost all of them, returning home with great spoils.

The way in which the story is told is thought by some historians to emphasise the ‘feud’ aspects more than the political background. It is possible, however, that the killings were also a part of a wider political picture involving Northumbrian politics and the accession of Cnut to power in England, and the continuing antagonisms between Anglo-Scandinavians and English Northumbrians. The only thing we can be sure about (if we take the incidents at face value) is that there were very dangerous games being played out at the top of Anglo-Saxon politics.

Hostages, Oaths, Treaties and Treachery

Bargains made and broken involving the exchange of hostages and the swearing of oaths were such an important part of Anglo-Saxon warfare that scarcely an event was recorded without such an accompaniment. It is the glue that held the model of the political world together. By looking at the nature of such agreements it can be shown that the familiar tools used to cement agreements varied wildly in their effectiveness. The study of this one phenomenon alone can explain so much about Anglo-Saxon history.

There were a number of ways in which the leaders of early Medieval England could seek to cement an agreement or alliance. For Christian parties there was the baptismal sponsorship or god-parenting arrangement. Also, there was the marriage alliance, particularly effective if the leader in question had several available beautiful sisters at his disposal, as did King Athelstan at the beginning of his reign (924–39). Athelstan was also a master of the fostering ploy as well. He fostered Haakon of Norway as part of a peace agreement made by his father. But not everyone was blessed with the power and political tools of the mighty King Athelstan. For most leaders, the keeping of an enemy to an agreement was done with the sometimes gritty and risky method of the hostage exchange.

The Anglo-Saxon era is littered with a macabre history of the fate of hostages. It is a history that makes for unpalatable reading for modern minds. The making of a binding agreement with an enemy by exchanging hostages and swearing oaths might seem fairly watertight, but all too often one side or the other (frequently the pagan Danes) treated those who they had exchanged with little regard. And so it was with the swearing of oaths. Such oaths were only worth something if they were sworn on relics or holy items that actually meant something to the oath taker.

Hostage exchanges had long been used throughout Early Medieval Europe. The Old English word for a hostage was ‘gisl’. This word is similar to the Irish ‘giall’ and to the Welsh ‘gwystl’. A hostage could be of a noble background, kept at the court of his captors to ensure the good behaviour of his own master, the captors’ enemy. They could also be members of a fighting force whose leader had been coerced to come to terms with his enemy.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle first mentions a major use of hostages in the period covered here in an entry for 874 after the Danes had driven out King Burgred of Mercia (852–74). Here, the scribe says:

they [the Danes] granted the kingdom of Mercia to be held by Ceolwulf, a foolish king’s thegn, and he swore them oaths and granted them hostages, that it should be ready for them whichever day they might want it, and he himself should be ready with all who would follow him, at the service of the raiding army.

Exactly who Ceolwulf’s hostages were is unknown, but it is likely they were valuable to him. These men may even have been chosen by the Danes themselves, who were holding all the cards at this time. Contemporary observers such as Asser saw this whole thing as a ‘wretched’ agreement, a comment that reveals the likely effectiveness of the arrangement.

The next mention of hostages is in 876. This time, with Alfred cornering his enemy at Wareham, the impetus was apparently with him. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that the king made peace with the Danes, possibly implying a cash payment (as the chronicler Æthelweard also implies), but that the Danes ‘granted him as hostages the most distinguished men who were next to the king in the raiding army, and they swore him oaths on the sacred ring, which earlier they would not do to any nation, that they would quickly go from his kingdom . . .’. Alfred had learned from his own dealings with the Danes and from what he had heard about similar arrangements in Francia. The Danes did not care much about keeping an oath sworn on Christian relics. This time they had sworn an oath on their own holy ring, possibly an arm ring of the type associated with Thor. But if Alfred thought this was enough to bind his enemies to their agreement, he was to be mistaken. The king had given his own hostages to the Danes in what was an exchange as opposed to a one-sided agreement. Asser tells us that during one night the Danes left Wareham and killed all their hostages, breaking the treaty and headed for Exeter. We can only guess what Alfred did with the men he had received as hostages on hearing this news.

Guthrum, the Danish leader in all these negotiations, made it to Exeter with his mounted army and sat there confident that he had played a master stroke and had got himself out of a tight corner at Wareham. Alfred’s men had not spotted his night exodus, and had played catch-up to no avail arriving at the gates of Exeter when the Danes were already safely ensconced. Guthrum was also expecting a fleet of 120 ships to arrive and aid his bid, but when these vessels left Poole Harbour, rounding the headland off Swanage, they all succumbed to a storm and were lost. Consequently, Guthrum was once again on the back foot with an English army at his door. And with this development we see yet another turn in the story of the hostage exchange.

The hostage ploy seems now to have favoured Alfred. It may seem surprising that there was an exchange as opposed to a one-sided Anglo-Saxon arrangement given what had happened to the English hostages at the hands of the Danes at Wareham, but conditions were not yet perfect for Alfred, he was just in the ascendancy. This time, the Danes granted him ‘as many hostages as he wished to have’, implying that the king was able to pick them. What followed this Exeter agreement, again sworn on oath, was the departure of the Danes from Wessex and their subsequent settlement of parts of Mercia which the puppet English King Ceolwulf had held open for them.

Clearly, hostage negotiations in the ninth century were a bloody and dangerous game. Each phase in a campaign seems to have involved an upping of the stakes for both sides. Alfred’s subsequent misfortunes in the wilderness of the Somerset marshes are well documented for the year 878. However, his famous victory against the Danes at Edington was so decisive that it led to a further development in the art of the hostage negotiation. A fortnight passed with the English camped outside of the Danish camp to which their army had fled after its defeat. Starving, cold and fearful, the Danes came to the English seeking surrender on terms more onerous than ever before. They would give hostages again, just as many as the king wanted, and this time they would demand none in return. No such arrangement had ever been made before. This was as close as a Viking army of the ninth century could get to abject defeat in a campaign. It was followed by the baptism of Guthrum (now to be given the English name Athelstan) at Aller and an additional ceremony at Wedmore some weeks later. Guthrum would rise from the baptismal waters as a Christian leader in a Christian land. The Danes would indeed leave Wessex, providing Alfred with breathing space to rebuild an expanded kingdom.

It happened again in 884–5 at Rochester, but this time the mention of hostages is different. A Viking force, which had been terrorising Francia for the opening years of the 880s, came from Boulogne to try its luck in Alfred’s new kingdom. It came expecting to wreck the place. They had brought many horses with them, fine mounts from Francia. But they had brought something else, too. Their army consisted of an unknown number of Frankish hostages. Alfred cut a dashing figure by 885. His army and fortification system were organised to cope with such an event as this new invasion (see pp. 88–93). The garrison at Rochester proudly withstood. Alfred came to relieve the men of the town. The Vikings, as a result, fled back to Francia without either their horses or their hostages, two vital accessories of warfare. The fate of these hostages is unknown, but they are most likely to have been truly rescued by the king of the Anglo-Saxons. For those Danes who had chosen to stay in England after their defeat at the hands of Alfred, hostages were once again exchanged, perhaps in the old style. But also in the old style, these Vikings twice broke their agreement and sent raids into the wooded heartlands of southern England. Some things, it seemed, could not change.

The agreement between Alfred and Guthrum, who was now ruler of East Anglia, was bound by a treaty referred to as the Treaty of Wedmore. It effectively divided England into a Danish and an English-controlled half. From now, to the north of Watling Street which stretched from London to Chester, there would be a land that would be under Danish-inspired law, a land that ultimately became known as the Danelaw. Alfred and his family were left with the rump of English Mercia and Wessex from which to provide the platform for a re-conquest. The surviving copy of the document that outlines the treaty probably refers to the settlement arrived at between the two sides after a period between around 880–6 when the countryside to the north of London was very much up for grabs. Here again, after much bloodshed and double dealing, we have mention of hostages:

And we all agreed on the day when the oaths were sworn that no slaves or freemen might go over to the army without permission, any more than any of theirs to us. If, however, it happens that from necessity any one of them wishes to have traffic with us–or we with them–for cattle and for goods, it is to be permitted on this condition, that hostages shall be given as a pledge of peace and as evidence whereby it is known that no fraud is intended.

So, in this new Anglo-Danish world, hostages could be given as surety against fraudulent trading activity. We can only imagine how many people were dragged across Watling Street from one side to the other to provide confidence in a trading deal.

As Alfred progressed with his grand military and ecclesiastical reforms, the years went by with no recorded deals involving hostages. It was not until the return of the Vikings in 892 that the campaigns began again in earnest. A Viking army with its 250 ships came to Appledore, and new leader Hæsten’s 80 ships came to Milton Regis threatening to cut off a giant corner of the country from the English king. Moreover, although Guthrum was now dead, the Danish-led armies of East Anglia and Northumbria were full of confidence and prepared to help their cousins assault the king of the Anglo-Saxons once again. This is why Alfred needed yet another hostage arrangement.

Alfred managed to secure oaths from the Northumbrians and the East Anglian Danes not to attack him. He procured six ‘prime’ hostages from the East Anglian Danes, although we are not told how. We are informed, however, that the deal was not kept to, as it seems the English-based Danes kept helping their cousins in the south east of the country by aiding their raiding and foraging activities during this uneasy stand-off. The fate of the ‘prime’ six is not recorded.

The Appledore Danes, laden with booty from their periodic raids, soon attempted to push north to find a ford across the Thames with the intention of making it to Essex to join with other Viking ships there. It ended in disaster for them, with Alfred’s son the ætheling Edward (soon to be king himself) intercepting and defeating them at Farnham. Edward drove them across the Thames at a place where there was no ford. Soon they found refuge of sorts on a river island near Iver in Buckinghamshire known as Thorney. Edward began a protracted siege which came to an end when the English system of military rotation meant that that besieger’s supplies had run out and their time in the field was up. Unfortunately, this all happened before King Alfred was able to relieve his son. We are told, however, by the chronicler Æthelweard that the Danes who had been surrounded and starved at Thorney Island and whose leader was wounded did exchange hostages and agree to leave the kingdom. To Essex they went, to join up with Hæsten’s force which had now relocated to Benfleet.

Alfred, at some stage during this campaign decided to attempt to bring Hæsten to heel through the offer of baptism, with the king himself standing sponsor to one of the Viking’s sons and Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians to the other. We know less about it than we do of the arrangements made with Guthrum. Hæsten’s base at Benfleet was eventually captured by the English in a siege that saw women and children, ships and money seized and brought to London. Also seized by the besieging Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, were Hæsten’s sons. The Dane had been out on a raid when all this happened. The young men were sent to Alfred’s court, probably in the hope they would prove to be very valuable bargaining chips. But Alfred sent them straight back to Hæsten delivering a message of extraordinary mercy for these times. Perhaps it is fair to say that Alfred knew he had his enemy defeated, but he seems not to have been able to hold his own godson as a hostage.

The Vikings’ subsequent movements to Buttington and Chester both ended in sieges which saw great suffering for the enemies of Alfred. At Buttington, Æthelweard tells us that ‘they [the Danes] did not refuse hostages, they promised to leave that region’. In 894 Æthelnoth, Alfred’s trusted ealdorman from Somerset, visited York in an ambassadorial capacity with a view to persuading the Northumbrian Danes to cease their pillaging of parts of Rutland held by the English under the Alfred and Guthrum treaty, but again we do not know how this deal was cemented. What we do know is that by the time the Danes had been outwitted by Alfred’s clever fortifications surrounding their ships at Hertford in 895, the Danes, under a new leader following Hæsten’s death, moved out to Bridgnorth from where they dispersed never to reform again.

The historic record falls quiet in respect of hostages towards the end of Alfred’s reign. When Edward took the throne after the death of his father in 899, there was a revolt against him from Æthelwold, the son of Alfred’s brother Æthelred I. This revolt, which is documented below (see pp. 101–4), involved the pretender to power taking a nun against the king’s leave before stealing away from the watchful eyes of Edward’s army in a dash to Northumbria. It is not known if the nun was a hostage, had been kidnapped or was a willing participant. However, to take a nun from a nunnery without the bishop or king’s permission was a ‘criminal’ offence and clearly Æthelwold was using this as a way of defying Edward.

The next reference to hostages is only by inference. In 906 Edward is said to have ‘confirmed the peace’ at Tiddingford with the Northumbrian and East Anglian Danes. No mention is made of an exchange, but from what we have observed already it is an agreement likely to have involved them. We can be more certain of the next mention, however. Edward, by 915 had succeeded in defeating the Danes and had embarked on his great re-conquest of the midlands. But in this year, a Viking force had come from Brittany led by Jarls Ohtor and Hroald (sic) and it headed up the Severn raiding as it went. The force went into Wales and took a bishop named Cameleac, Bishop in Archenfield, as hostage. Edward then paid 40 pounds to ransom him back, one of the few recorded arrangements of this kind. As the Vikings headed to Archenfield for richer pickings, they were met by the men of Hereford and Gloucester and nearby forts. The resulting battle saw Ohtor and Hroald defeated with Hroald perishing and Ohtor’s brother also being killed. The Vikings were subsequently driven to an ‘enclosure’ where they were besieged until they gave hostages in return for leaving the kingdom. It sounds as one sided as some of the later Alfredian agreements, but the reality was that the force hung around for some time on the Severn Estuary embarking on sporadic raids before eventually leaving for Ireland.

Edward’s sister, the famous Æthelflæd, sometimes called ‘the Lady of the Mercians’, had her part to play in the history of the hostage. It was she who in 916 sent a force to Brecon Mere in Wales to break down the fortification there and in doing so took the wife of the Welsh king of Brycheiniog ‘as one of thirty-four’, says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. There would be many more organised strategic conquests of such citadels as Danish Derby and Leicester, the key boroughs of the Danelaw. Just before her death in 918, the chronicler tells us, Æthelflæd after taking Leicester had even got the leaders of Viking York to swear oaths that they would be at her disposal. They did not keep to this, of course, but the fact that the agreement happened at all is testimony to the increasing power being displayed by Æthelflæd and her brother Edward south of the Humber. As more Scandinavians poured into the northern parts of Britain, the Danish forces of yesteryear, now settled in England, began to see the sense in aligning themselves with the resurgent Anglo-Saxon monarchy in the south. In fact, before he died in 924 Edward the Elder had secured the allegiance of the Scots, a new Norse leader at York, the lords of Bamburgh, the king of the Strathclyde Britons and the Northumbrians of all cultures.

At Æthelflæd’s death an event took place that has received a number of interpretations. The Mercian Register of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in an entry for 919 records it thus: ‘Here also, the daughter of Æthelred, Lord of the Mercians, was deprived of all control in Mercia, and was led into Wessex three weeks before Christmas; she was called Ælfwynn.’ The most likely interpretation of this is that it was no simple hostage taking, but a political abduction. Edward the Elder, who had achieved so much in alliance with Ælfwynn’s mother (his own sister), could not afford for the spectre of Mercian independence to raise its head just when it looked like the Kingdom of the English was finally taking shape under his own leadership. In Ælfwynn many traditional-minded Mercian noblemen may have seen a standard bearer for that independence. So, the king spirited away his own niece to avoid this happening. The Kingdom of the English was growing in confidence.

King Athelstan’s (924–39) use of human resources was a far cry from the desperate hostage exchanges of the Alfredian campaigns. A kingdom of England was very much in the making now, and Athelstan’s negotiations were on an international level, binding his kingdom into the fortunes of, among others, the great Holy Roman Empire controlled by the Ottonian dynasty. In the sparse entries for Athelstan’s reign in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle there are hints at hostages, however. In 934 for example, Athelstan’s combined campaigns by land and sea in Scotland resulted in the Scottish King Constantine having to give his own son as a hostage.

There is no mention of hostages in the years preceding Athelstan’s great Battle of Brunanburh of 937. During these years, an imperious Athelstan, able to draw an army from the length and breadth of his new kingdom did indeed hold imperial-style councils at places like Cirencester, calling in tribute from the Welsh kings which amounted to huge quantities of gold, silver, oxen, hounds and hawks. But the Scots and the Norse-Irish led a confederacy against Athelstan at Brunanburh, at a battle site that is still to be identified with certainty. Once again, even in their crushing defeat there is no mention of hostages from the lords of the north, just a mention of them fleeing the field for home.

It would seem that Athelstan’s victories might have paved the way for a Golden Age in Anglo-Saxon kingship, but this was yet to come. Olaf Guthfrithson, the enemy who had caused the great king so much trouble, swept back into the picture after Athelstan’s death on 939. A complex marriage alliance in the midlands with the daughter of a Danish jarl, and some military campaigning in the north, saw the Dane in the ascendancy again. It was Athelstan’s younger brother, King Edmund (939–46) who had to re-capture the five Danish boroughs of the midlands for the southern English crown. In 943 a new enemy, Olaf Sihtricson, had taken Tamworth from the English and had fled to Leicester. In time-honoured style, we are told this was the same year in which this Olaf received baptism with Edmund as his sponsor. But the records of the tenth century are more complicated than those of other eras. There are allusions to further submissions in York, for example, but we are not told how these arrangements were cemented.

On Edmund’s death in 946, he was succeeded by another brother Eadred (946–56), who in the first year of his reign conquered Northumbria and was granted oaths by the Scots ‘that they would do all that he wanted’. More oaths then, but no details. At Tanshelf, in 947 Archbishop Wulfstan of York and the councillors of the Northumbrians are said to have pledged themselves to the king, but ‘within a short while they belied both pledge and oaths also’. The reason for this recalcitrance lay in the arrival of a famous Viking leader, one Eric Bloodaxe whose control of the Viking kingdom of York quickly became legendary. Eric, who held Northumbria from an apparent promise made by Athelstan, was eventually defeated, murdered by one of his own men after the grim campaigning of Eadred in the area.

The brief reign of Edwy, king in Wessex (955–9) records no hostage exchanges, but plenty of domestic politicking. Edwy’s grip on power subsided as his brother the young Edgar (959–75) gained acceptance in both Mercia and Northumbria and eventually Wessex itself. Edgar’s reign over England was one of peace bought by the threat to any enemy of overwhelming military force. A huge and energetic navy and a vast land army were enough for Edgar to concentrate on matters such as monastic reform and other political issues. In an act of overwhelming symbolism the king took an army to Chester. Here, at the edge of the old Roman world, King Edgar symbolically took the helm of a rowing vessel and was rowed by up to eight subservient leaders on a boat along the River Dee to the monastery of St John the Baptist. Oaths were sworn, and the promise from all these rulers was that they would be faithful to the king of the English and support him both on land and at sea. These men were Malcolm, king of the Cumbrians; Kenneth, king of the Scots; Maccus, king of ‘Many Islands’; Dunfal (Dunmail), king of Strathclyde; Siferth; Jacob (Iago of Gwynedd); Huwal (Jacob’s nephew and enemy); and one Juchil. Edgar’s passing remark after this event would ring in the ears of regional kings for centuries. Any of his successors, he said, could pride himself on being king of the English having such subservience beneath him.

On Edgar’s death in 975, Anglo-Saxon England was at its peak of power and influence. He was succeeded by his son Edward (975–9) whose reign leaves no record of hostage giving or oath taking. However, after Edward’s infamous murder at Corfe Castle and the rise to power of his half brother Æthelred II (979–1016) we enter a period of history whereby the role of the hostage once again leaps out from the pages of the chronicles and histories.

Æthelred’s reign was a little over eighteen months old when the Scandinavian raiders returned to England. Southampton was targeted first and we are told that many of the inhabitants were killed or taken prisoner. We are not told of the fate of these hostages, however. Nor are we told what happened to the people of Thanet in Kent and the region of Cheshire who also suffered similar fates. Soon, in 991, the Battle of Maldon would be played out in Essex (pp. 117–20) between the local ealdorman Byrhtnoth and an invading Viking force. Here again, there is a mention of a hostage, but he is this time a Northumbrian hostage in the East Saxon Army. Pointedly, he is mentioned as having a bow, not a sword as one might expect. It is possibly an interesting glimpse into the equipment allowed for hostages when asked to participate in their captors’ campaigns.

Hostages were once again exchanged in 994 when the legendary Olaf Tryggvason and Swein of Denmark unsuccessfully attacked London. The chronicler Æthelweard, who, as we have observed, was a nobleman himself, played his own part in this negotiation as he and the Bishop of Winchester arranged for hostages to be sent to the Danish ships and for Olaf to be brought to King Æthelred for a baptism perhaps in the style of that which had happened to Guthrum all those years ago. Olaf’s interests would soon turn to Norwegian matters, but it remains the case that after this agreement with Æthelred, he never returned to England.

The later part of Æthelred’s reign saw the usage of hostages become widespread. Nothing, however, would quite match the drama of the fate of one man in particular whose fame throughout the northern Medieval world was eclipsed only by that of Thomas à Becket 150 years later. The Danish assault on Canterbury in September 1011 marked a notorious episode in the king’s reign. The Danes, when they entered the city, are supposed to have gone wild. Their rampage resulted in the capture of Ælfhere, the Archbishop of Canterbury and one Ælfweard, a king’s reeve, among others. Christchurch was plundered and countless people murdered in a long-remembered orgy of destruction.

The Danes stayed the winter in Canterbury. They suffered from illnesses brought about by the apparent unsanitary water supplies, but this much divine intervention was not enough to rid the English of their tormentors. It was, however, their key hostage whose fate attracted the attention of chroniclers. Not content with the silver offered to them to leave, they asked also for a ransom for the return of the archbishop. Ælfhere would have none of it. For his intransigence the pious archbishop was murdered at the hands of his captors in Greenwich. In a drunken frenzy, here at the termination of the Rouen to London wine trade route, one Dane pulverised the head of the archbishop with the butt end of his axe while the others hurled cattle skulls and bones at him on the hustings. The hideous event was carried out against the wishes of an observing Dane called Thorkell the Tall and it was an event that marked the beginning of a significant switch in Thorkell’s allegiance from the side of the Dane to that of the English king himself (pp. 63–4).

From the story of one famous hostage, we go to the handing over of countless people to the Danish King Swein in 1013. Swein, who had long harboured a bitter resentment against Æthelred, had sailed down the Humber and Trent to Gainsborough and called to him the men of Lindsey, those of the Danish Five Boroughs of the Danelaw (Nottingham, Stamford, Leicester, Lincoln and Derby) and Earl Uhtred of Northumbria. Their allegiance was cemented by supplies of hostages from ‘every shire’–a figure that must have been considerable. Some time after the hostages were given, Swein entrusted them to his son Cnut. It was a move that would have profound ramifications. Swein poured his forces south across Watling Street and fell upon Oxford, the townsfolk of which provided further hostages to him. Next, it was Winchester’s turn and in an embarrassing exchange for the English king, the Oxford story repeated itself. The beleaguered Æthelred and his new ally Thorkell remained in London, contemplating. It would not be long before the king would sail to Normandy, to the home of his wife Emma and into exile.

In February 1014 Swein unexpectedly died. He was succeeded as nominal king in England by his son Cnut. However, many Englishmen appealed to the exiled Æthelred to return to England and rule once again as their natural lord, although there would be conditions in the bargain. Æthelred did indeed return and not long after this he conducted a punitive campaign of destruction in Lindsey against the land of Cnut’s supporters. Cnut then decided to sail down the east coast of England to Sandwich where he dropped off those English hostages his father had passed to him, each with their hands, ears and noses cut off before they were put to shore. Then, after this grisly act, the would-be Danish king of England set sail for Denmark.

Cnut did, of course, return to England. Through the political machinations of one famously seditious Eadric Streona, a turncoat English earl, he secured a hold on power. But in an unlikely turnaround Edmund Ironside, the son of Æthelred, found himself with the support of the Danelaw (through marriage) ranged against Cnut and Eadric based in the south of England, the traditional strong areas for the family of Edmund. With a reluctant King Æthelred lying ill in London, there began a giant circle of campaigning across the country which also involved Uhtred of Northumbria, whose grisly end we have already observed (see p. 23). Soon Æthelred would die in London and there began a siege (see pp. 143–4) and subsequent campaigns in Wessex between Cnut and Edmund which eventually ended in a pyrrhic victory for the Dane.

The situation in London, if the chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg is to be believed, was full of dramatic bargaining. Emma of Normandy, Æthelred’s widow, was to hand over her sons ‘Ethmund’ (Edward) and ‘Athelstan’ (Alfred). These were her sons and heirs to the English throne, but they are both said to have escaped in a boat. A tangled tale then ensued involving the mutilation of a great many English hostages. We shall never know the truth about the fate of the hostages or their exact numbers. Thietmar has his critics when it comes to his accounts of these important events in London.

Further sieges at London and pitched battles in the countryside around Wessex between Edmund and Cnut followed this episode. Eadric Streona subsequently changed sides and when supporting Edmund bitterly betrayed him on the battlefield at Ashingdon. The agreement finally reached between Edmund and Cnut, at an island in the River Severn after they had fought each other to a standstill up to this point, saw the English king hold Wessex and the Dane hold the rest of the country including London. Once again, the agreement was sealed with hostages. There is also a hint in the sources that Edmund offered single combat to Cnut, but nothing is really known of it.

On 30 November 1016 Edmund Ironside died. The finger of suspicion surrounding his death was historically pointed at Eadric Streona, but no absolute proof has ever been offered. Cnut in an instant took the throne of the whole of England. Throughout his reign he ruthlessly dispatched his political enemies and always seemed to be aware of the potential of the popular appeal of the line of Cerdic, Æthelred’s ancient royal family. Political assassinations meant that his grip on power became stronger and there is no evidence of any significant hostage exchanges for many years. But in 1036, after Cnut died, there was one hostage whose fate was every bit as significant as that of Archbishop Ælfhere a quarter of a century earlier. Earl Godwin, a favourite English magnate of Cnut’s, whose new allegiance was very much in the camp of the new King Harold Harefoot (1036–40), was the main player in the drama of the murder of Alfred, son of Æthelred.

For the Normans, the death of Alfred would pretty much justify the entire Norman Conquest. Alfred, half Norman himself, was on his way to meet his mother Emma. Having landed at Dover and tracked his way towards Winchester, Alfred and his followers arrived at Guildford where they were met by Godwin and his men. Alfred was carried away and taken hostage to Ely where he was brutally blinded. The others were either killed or sold into slavery. It was a horrible affair. Although the Norman chroniclers never forgave Godwin for his role in the taking of Alfred, Godwin would later atone for it when Harthacnut (1040–2)–Alfred’s kinsman–came to power. As king of England, Harthacnut made Godwin stand trial for the crime and received from the powerful earl a magnificent ship complete with its warrior complement for his compensation.

The early years of Edward the Confessor’s reign (1042–66) saw no significant usage of hostages as such until 1046, when Earl Swein, the eldest son of Earl Godwin and whose new earldom bordered southern Wales, went into that country in force. He allied himself with Gruffydd ap Llewelyn, king of Gwynedd and Powys, and was granted hostages by his southern Welsh enemies. Their fate is unrecorded. The Godwin family would, however, continue to dominate the politics of King Edward’s reign, but it was with the old man Godwin that things would come to a head between king and earl and once again hostages would play their part.

There followed royal appointments of Normans, the building of castles in Herefordshire and Dover and one infamous visit to England by Eustace of Boulogne, whose men ran amok in the streets of Dover. These were just some of the reasons for the tensions between Godwin and King Edward. By 1051 Godwin had had enough of it all. He had raised a huge army from his own Wessex combined with Earl Swein’s men from Oxfordshire, Herefordshire, Somerset and Berkshire and Earl Harold’s men (the future king) from East Anglia, Essex, Huntingdon and Cambridgeshire. At Tetbury, just 15 miles away from a concerned King Edward, this force came together. A demand was sent to the king by the earl. There will be war unless the king gave him Eustace of Boulogne and the men ‘who were in the castle’, a reference possibly alluding to either the castellans of Dover or the notorious Herefordshire Normans. But against Godwin would be ranged the forces of Earl Siward of Northumbria and Earl Leofric of Mercia, plus a contingent of knights from Earl Ralph the local Norman. Once these forces had been gathered after urgent messages were sent to the north there was something of a stand-off. It seemed to those present that a battle between the finest men of England in a time of foreign interest in the English throne would be of such grave consequence that it should not be allowed to go ahead. The situation was therefore resolved with the exchange of hostages and the arrangement that there would be another meeting on 24 September between the protagonists in London.

Godwin fell back to Wessex in the meantime and the worried king took the time he had bought to raise a huge army from Earls Leofric and Siward’s lands and bring them to London for the meeting. This took around two weeks. At London the net was closing in on Godwin and his family. Godwin asked for safe passage when he was at Southwark, but this time the hostages were refused him. The upshot of the meeting was that he was outlawed along with Swein and Harold. They had to leave England. Before they did this however, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that the thegns of Harold were ‘bound over’ to the king, indicating that a shift in lordship bonds of Harold’s followers was part of the punishment. So, as a ship was prepared at Chichester Harbour the Godwin family sailed off to the court of Baldwin of Flanders, all except Harold who sailed via Bristol to Ireland. At this time it is thought that Wulfnoth, Harold’s brother, and Hakon, Earl Swein’s son, were given to the king as hostages. The way was clear for a young man from Normandy–Duke William–who had been promised the throne of England to pay a visit to Edward’s kingdom.

Godwin was no fool. On 22 June 1052 he left the Yser Estuary with a small fleet and evading Edward’s forty ships at Sandwich, he landed on the Kentish coast. His former men in Kent came to him as did the ship men of Hastings and the men of Sussex and Surrey who declared they would ‘live and die with him’. The earl’s son Harold joined forces with him and between them they gathered a force large enough to intimidate the king on his own doorstep in London. Godwin had made the most triumphant of returns. In the subsequent scramble for safety, the Norman Archbishop of Canterbury Robert of Jumièges may well have taken Wulfnoth and Hakon to Normandy as he and others fled the vengeful Godwin family, handing the hostages over to Duke William.