Chapter 5

Campaigns, Battles and Sieges

Campaigns

871: Wessex Takes on the Great Heathen Army–a War of Attrition?

The nature of the campaigning against the Great Heathen Army and its detachments prior to the watershed Battle of Edington in 878 was characterised by closely fought battles which brought Alfred the Great’s Wessex almost to its knees. Here, we shall look at the campaigns of 871 which represented the most desperate fighting seen in England since the fall of Roman Britain many centuries before.

The Danish army ‘of hateful memory’ was led by Halfdan, son of Ragnar Lothbrok, and at least one other Danish leader for whom we have a name, Bagsecg. We cannot be sure how big it was, perhaps only 1,000 men or maybe more, but its activities had already devastated those ancient kingdoms it had passed through. In the autumn of 870 it decided to leave its East Anglian base and headed to Reading, a royal estate in Berkshire. At the confluence of the rivers Kennet and Thames, the Danes set themselves inside a remarkably well-defended fortification, which comprised one long ditch cut from one river to another, probably moated and palisaded with gates at intervals. The route the Danish army took to Reading is not known. It is likely Halfdan began his journey from Thetford in East Anglia on the Icknield Way. If he had chosen to avoid London, where there may well have been another Danish attachment, then he will have followed this ancient roadway to Royston, Wilbury Camp, Offley, around Dunstable, finally crossing the Thames at Goring. Whichever way he got there, Halfdan arrived at Reading and began his fortification unmolested while he waited for a naval contingent to join him.

Reading was a wise choice for Halfdan. Like any royal estate, it had resources at hand. Such places were the centres for the food rents and dues owed to the Crown. In the winter the estate will have been well stocked for the oncoming months. Nearby, there was the abbey at Abingdon, itself a huge repository of food, wine and portable wealth. And so Halfdan sat there, hovering menacingly above Wessex, preparing to do to Æthelred I’s kingdom exactly what his Danes had done to East Anglia.

It was now deep into winter. It was Christmas time, and the Danes were quickly set in their camp with Halfdan presumably predicting a lack of activity against him from the West Saxon brothers over this period. But if this was true, one man had been keeping a close eye on the invaders and he would soon spring into action. Halfdan and Bagsecg had only three days to think about their strategy before having to reassess the situation. Nobody knows quite why Jarl Sidroc sallied out of the gates at the Reading camp on New Year’s Eve, but it reports like a foraging or scouting party, perhaps even a reconnaissance-in-force to examine the local route ways and options for his master. Around the north of the Great Windsor Forest he travelled, clinging to the banks of the Kennet, coming out onto the ‘plain of the Angles’ at Englefield through which a Roman road passes. He was already around 10 miles from camp.

The Danish detachment was pounced upon by Ealdorman Æthelwulf of Berkshire, a man who had undertaken a similar surprise attack on Weland, the great Viking raider, in 860 after the burning of Winchester. Æthelwulf, a shadowy figure, seems to have been widely revered. Clearly, he carried a reputation of sorts for military prowess and he would not fail to impress here. Caught in the open country, Jarl Sidroc and another leading Dane paid for their reconnoitre with their lives as they were cut down in the plain. As the survivors fell back to the camp and the gates were opened to the sorry wounded, Halfdan and Bagsecg will have been surprised that Wessex had such a loyal friend patrolling Berkshire. But for all his guile, Æthelwulf’s strategy seems to have been to teach a detachment a lesson in the landscape, and not to besiege or defeat the Great Heathen Army itself. For this to happen, he would have to send news of his victory to Æthelred and Alfred in Wessex with a plea for aid. Just four days later the West Saxons arrived at the gates of the Reading camp fully equipped for war.

Some Danes working outside the gates of the camp were cut down by the arriving English army. At some stage the Danish leadership made a quick–and as it turned out–decisive choice of action. The Danes from within the camp burst out of their own gates with an overwhelming ferocity which saw a hard-fought pitched battle commence. During this battle Æthelwulf, the loyal ealdorman, perished and the West Saxon brothers had to call a retreat. It was an ignominious defeat for a force that should have been capable of managing an effective siege. The extent of the defeat and the disorganisation of the Wessex men in the rout is captured by Gaimar, a later (twelfth-century) writer, who gives us a clue that the English, despite their panic, not surprisingly had the better knowledge of the local topography:

There was Æthelwulf slain,

The great man of whom I just spoke,

And Æthelred and Ælfred

Were driven to Wiscelet [Whistley].

This is a ford towards Windsor,

Near a lake in a marsh.

Thither the one host came pursuing,

And did not know the ford over the river [Loddon].

Twyford has ever been the name of the ford,

At which the Danes turned back,

And the English escaped.

It is this knowledge of topography that would prove crucial in the days and weeks to come, especially the knowledge of fordable points across the rivers. Streatley, Moulsford and of course the strategically important Wallingford would all play a part in what was to come. But why had the attempted siege at Reading failed so badly? Was it because the encounter at Englefield had only really been a mere skirmish and the Danish losses had not been so great after all? Or was it because the Danish tactic of a surprise rush from the gates of their own camp had brought about the desired effect of scattering their enemy? Perhaps the Danes were not such a small force after all. They had at their rear a ‘friendly’ River Thames. It is not inconceivable that the force at Reading had been swollen by the arrival of new Danish reinforcements in the days leading up to the siege there.

Whatever the size of Halfdan’s force after Reading, it was clear to the leadership that they could not stay there. The West Saxon brothers would come again soon and when they did, they may have learned something about how to conduct a siege properly. The Danes must now push out into the countryside to search for more resources and to occupy strategically important locations. It would seem that Wallingford was just one such place. It took only four days for the royal brothers of Wessex to reorganise themselves. They may have gone to Abingdon. Perhaps the Danes were seeking them out, trying to bring about a conclusion to decide once and for all the fate of Wessex, despite the risks that might pose for them. Whatever the reasons, the West Saxons were ready for the Danes. Halfdan had left Reading on the morning of 8 January 871 and when he had got about 12 miles from his base as he climbed the hill at Moulsford he saw across from him a huge English army, which had positioned itself on Kingstanding Hill across the Icknield Way awaiting its enemy. It was a well-chosen position for the English. They had blocked the Danish advance and left Halfdan pondering his next move. He could try a quick slip to his right into the inviting but small gap the English had left between themselves and the river, risking being driven into it, or he could try to slip round to the left of the English army as he saw it, in the knowledge that they had put themselves there with a far superior understanding of the local roadways and would surely be upon him before he could get round them.

Halfdan divided his force into two divisions, one comprising ‘kings’ and the other of ‘jarls’ and it became clear to a watchful Alfred that the jarls’ division was making a move for the gap. With history famously recording King Æthelred’s devotion to prayers at this time, it was Alfred who crossed the valley and rose up the hill to smash into the Danes and press them towards the river. The young prince would win his spurs here at the Battle of Ashdown, as it became known. Æthelred would soon join in the fray against Halfdan’s division. The outcome was a resounding victory for the Anglo-Saxons, a brilliantly engineered pitched battle on a ground more or less of their own choosing. The chase went on long into the night. Among the dead lay Bagsecg. With him had perished Jarl Sidroc the Old, Jarl Sidroc the Younger, Jarl Osbern, Jarl Fræna and Jarl Harold. Many of these names seem to have belonged to the jarls’ division that had been pounced upon by Alfred. The Danes returned to Reading and began to wonder how they could fight their way out of this corner. Wessex was proving stronger than they had imagined.

Around 22 January 871 the Danes opened the gates at Reading once again, this time with a view to marching on the Royal vill at Basing. It was just 18 miles from their camp and situated in Hackwood Park, east of Basingstoke. Nobody knows why after two weeks of contemplation the Danish leadership switched the focus of their campaign in the Wessex landscape. Previously, they had been attacking the north-east corner of Wessex in the hope that the Thames would open up for them and their allies and that they would be able to navigate all the way up to Cricklade and beyond. But now the Danes headed south and further into the heart of the kingdom. Perhaps Basing was the target after all, with its rich supplies. With Basing fallen, the road to Winchester lay wide open and despite there being a victorious English army in the field the taking of Winchester might be the telling blow against Wessex.

It would be the fourth battle in the space of a month. Many of the men on the Anglo-Saxon side would not have fought at Englefield as this was conducted by the men of Æthelwulf. However, many were under lordship obligations to continue to fight for Æthelred and Alfred, and by now they must have been feeling the pressure. The two royal brothers arrived at Basing and found the Danes there. What followed was another hard-fought and bloody encounter which resulted in the more traditional form of victory in that the Danes held the place of slaughter and the West Saxons took to flight to re-group yet again. But Winchester was not sacked or taken. One can only speculate as to why this was. Perhaps the cost of their strategy was proving as much for the Danes as it was for the English. Perhaps they needed re-enforcements to continue their campaign in Wessex. If that was the case, they would come soon.

Some time passed and there seems to have been a stalemate in the landscape. The brothers, it is suggested, had retreated to Walbury Camp, with its ancient protective ramparts and fine commanding views of the countryside. There was time even for the brothers to make an agreement as to the inheritance of the West Saxon kingdom should one of them die. But it was not until 22 March 871 that the Danes stirred again. The next battle was at a place called Merton, the location of which people have argued over for centuries. One of the most sensible candidates, given the previous movements of the armies, is Marten, 20 miles north of Wilton. Here the Inkpen Ridgeway would provide the means of travel for the combined fyrds of Berkshire and Hampshire. Why Merton was fought is not clear. And what happened there is only a little clearer and is mentioned if not by Asser, by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in a cryptic and sweeping entry:

And two months later, King Æthelred and Alfred, his brother, fought against the raiding army at Merton and they were in two bands, and they put both to flight and for long in the day had the victory, and there was great slaughter on either side, and the Danish had possession of the place of slaughter; and Bishop Heahmund [of Sherborne] was killed there and many good men.

It is an infuriating account. Why had the Danes formed into two divisions again? Had Halfdan been joined by another leader or should this command represent a promotion for someone already in his force? The chronicler follows up this passage by saying that only after Merton were the Danes joined by others. So the question remains, why did the English lose this close-fought battle? The answer probably lies in what happened to the king of Wessex a month later: Æthelred I, king of Wessex was dead. In his place was elevated Alfred, son of Æthelwulf of Wessex. This new king of Wessex, whose baptism of fire soon commenced, would make historians write his name a million times.

If King Æthelred had been mortally wounded at Merton, this might explain the English withdrawal from the conflict at this stage. Alfred went about the business of burying his royal brother at Wimbourne, the royal spiritual home of the West Saxon kings. But as he did, he realised that his kingdom was in dire trouble. He heard news that yet another battle was being fought, this time back in the north-east corner of kingdom. The chronicler Æthelweard–usually reliable–gives us the one and only account of it:

An innumerable summer army (Sumarliði) arrived at Reading and opened hostilities vigorously against the army of the West Saxons. And the ones who had long been ravaging in that area were at hand to help them. The army of the English was then small, owing to the absence of the king, who at the time was attending to the obsequies of his brother. Although the ranks were not at full strength, high courage was in their breasts, and rejoicing in battle they repel the enemy some distance. However, overcome with weariness, they desist from fighting, and the barbarians won a degree of victory which one might call fruitless.

If Æthelweard is correct, then the reinforcements had well and truly arrived. The tired West Saxons, without their king had at least managed to stand up to them, but now they were exhausted. If Alfred had not already stared into the faces of these new Danish leaders Oscetel, Anwend and Guthrum, then he soon would. Of these, the last named would haunt the West Saxon king for years. But for now, Alfred must reluctantly face the fact that a newly invigorated Danish force had moved once again into the Wessex heartland after defeating local armies. Its predictable target was another royal manor, Wilton. Another attempt to seize supplies and rob the king of an estate, perhaps even a terminal blow for the brand new monarch.

However weary, however depleted in manpower, Alfred stole himself for another encounter. It was a remarkable engagement fought on the banks of the River Wylie. The tactical dispositions are not known, but with his small force Alfred seems to have spotted something similar to what he saw on the field of Ashdown. Some sort of tactical evolution in Danish deployment, some small chance to capitalise on the enemy’s vulnerability. Alfred smashed into the Danes with such ferocity that they are described as not being able to withstand his onslaught. What seemed like a recoil became a retreat. But the English, small in number and war weary, were unable to follow up the success. The Danes displayed an ability to somehow turn on their heels and swamp their pursuers. This may have been because the English were literally too small in number for their chase to be anything other than plain dangerous, or it may have been because the Danes had initiated a flight intending to turn again on their foe. If it was the latter, it would be of some considerable note. This was a tactical ploy much vaunted in the age of the mounted knight and is very difficult if not impossible to effect with an infantry warband.

And so at Wilton, the new king of Wessex watched his brave men get swamped by Vikings in what seemed now to be a hopeless war of attrition. He was literally running out of men. Alfred decided to switch tactics completely and chose not men, but money with which to purchase an effective end to the hostilities. It must have seemed to the Danes under their new combined leadership, that although Wessex was still vulnerable and depleted, it nevertheless stood as a kingdom and they had not yet managed to destroy its line or break the spirit of the men. Somehow, even when the odds were against them, the leaders of Wessex kept turning up to fight. In the end it was just enough to save the kingdom from its first brutal encounter with the Great Heathen Army. As the peace was agreed and Alfred bought himself time to think, the Danes left their Reading camp and sat on London, then a trading settlement on the outskirts of the old Roman city. What lessons Alfred had learned from the year 871 only history would tell. He would be slow to understand it fully. He would not be free of the Danes until after 878 when he defeated them at Edington, but he was an intelligent and educated man. The measures he later took to fortify his kingdom would eventually bring this exhausting and attritional style of campaigning to an end, but it remains the case that the year 871 was an example of a type of warfare the English could not afford to fight against a well-organised and constantly replenishing Danish enemy.

900–5: The Revolt of Æthelwold–an Unlikely Apostate

Much mystery surrounds the career of Æthelwold, son of Æthelred I of Wessex. The campaign he led against King Edward the Elder (900–24) was motivated by Æthelwold’s persistent and understandable claim to the throne of Wessex. By this time, the kingdom was a much expanded polity created by Alfred the Great and it would soon be further expanded by his son and grandsons. Æthelwold’s story, however, demonstrates a certain trait in Anglo-Saxon warfare. The politics of dynastic struggles were never far away from the heart of warfare during our period. In 899, when Alfred, the ‘unshakable pillar of the Western peoples’, was laid to rest at the Old Minster at Winchester, one man would try to stake his own claim to the throne and would go to surprising lengths to achieve it.

Æthelwold was aggrieved at the terms of King Alfred’s will. He was the son of Alfred’s brother Æthelred I, who had been king himself and who had died at the height of the Viking struggles in 871 (p. 99). Æthelwold expected to be king of Wessex, no matter what Alfred had arranged for his own sons. It was, in effect, as simple as that. But not to Edward, son of Alfred, however. Alfred’s will had said something entirely different. Edward had already shown himself to be a remarkable commander in the final years of Alfred’s reign and it was clear to most contemporaries that Edward’s right to rule was quite legitimate. Edward had been made a co-ruler of the kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons in the last two years of Alfred’s reign. Edward’s young son Athelstan was born in 895 and quickly became a favourite of King Alfred, who had bestowed upon him gifts given to him by the Pope himself. It is even possible–if later Medieval historians are to be believed–that the young boy Athelstan was ‘inaugurated’ at a very early age. One can only imagine how Æthelwold fumed and plotted during the opening months of Edward’s reign. He was–to coin a phrase–being royally stitched-up.

Men of Æthelwold’s standing have their own retinues, their own supporters and followers tied to their lord by unbreakable bonds. Unsurprisingly, it was not long before Æthelwold made his move. He gathered those loyal to him and marched with them to the royal estates at Wimborne and Christchurch (then known as Twinham). The Danes themselves had executed a similar (and devastating) move at Repton, the seat of the Mercian Royal dynasty in order to crush psychologically King Burgred in 874. But here, Æthelwold was occupying the very place where his father had been buried all those years ago, the place where West Saxon legitimacy was marked by tomb after tomb. The pretender to Edward’s throne announced to the world that having taken Wimborne with his force he would ‘live and die there’. It was a challenge no son of Alfred the Great could ignore, so ignore it he did not.

Edward responded by bringing his own army to Badbury Rings, not far from Wimborne. The sheer size of the king’s army alone must have been enough to make Æthelwold consider his next move carefully. Edward knew of the nature of the threat. He will have been concerned that Æthelwold would gather more supporters by having brought off such an audacious move, but what surely concerned him the most was the nightmare scenario of a man of royal blood gathering support not from the Wessex heartlands where he would struggle for numbers, but from the power-hungry Scandinavians of the north of Britain. In the event, Æthelwold was ahead of his rival by a night’s march.

One night, during this uneasy stand-off Æthelwold took a horse and stole away under cover of darkness avoiding the scouts of Edward’s army. He left behind him a nun whom he had abducted in defiance of the king and the bishop, a deliberate act. He fled to the north and into the arms of the Northumbrian Danes. Edward’s riders could not catch him, so stealthy was his move. Æthelwold began a most remarkable relationship with the Danes which he backed up by some extraordinary promises. They accepted him as their king, but what price had he paid for their allegiance? The chronicler Æthelweard tells us there was in Northumbria that year ‘a very great disturbance among the English, that is the bands who were then settled in the territories of the Northumbrians’. Could it be that Æthelwold had revoked Christianity to entice an army big enough to challenge the king of the Anglo-Saxons? It would not be the first time in European history something like this had happened. Pepin II, a great grandson of Charlemagne, during a dispute with the Frankish King Charles the Bald had taken the Danes to his bosom in a similar way. The Annals of St Neots even describe Æthelwold as ‘king of the Danes’ and subsequently as ‘king of the pagans’ when he later made his return to the stage of English politics. Our great pretender, however, goes missing from the historical record for a year before his fateful re-appearance. There is speculation that he went to Denmark to gather a fleet and other reinforcements. He is next recorded bringing a fleet to Essex and gaining the submission of the local population there. Soon, he would lead his swollen forces into East Anglia and strike a deal there too. With the Scandinavian-dominated army of East Anglia, his own men and those of Essex, Æthelwold was a force to be reckoned with and Edward knew it.

The allies raided across Mercia from their East Anglian bases and came eventually to Cricklade, where they crossed the Thames. They took what they could from nearby settlements such as Braydon and turned east to go home. Edward went after them as quickly as he could and launched a punitive campaign across their own heartlands between the Devil’s Dyke and Fleam Dyke and the River ‘’Wissey’ (possibly the Ouse). Edward’s campaign stretched as far as the Fens. His Kentish contingent failed to answer his call to return home and was caught by the enemy. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records it thus:

Then they were surrounded there by the raiding-army, and they fought there. And there were killed Ealdorman Sigewulf, and Ealdorman Sigehelm, and Eadwold the king’s thegn, and Abbot Cenwulf, and Sigeberht, son of Sigewulf, and Eadwold, son of Acca, and many others in addition to them though I have named the most distinguished. And on the Danish side were killed King Eohric [the Danish ruler of East Anglia] and the Ætheling Æthelwold, whom they had chosen as their king, and Beorhtsige, son of the Ætheling Beorthnoth, and Hold [a minor nobleman] Ysopa and Hold Oscytel, and very many others in addition to them whom we cannot name now; and on either hand there was great slaughter made, and there were more of the Danish killed although they had possession of the place of slaughter . . .

The Kentish refusal to obey the king had nearly cost him dear. Despite his Kentish contingent losing the Battle of the Holme, as it became known, Edward had managed to rid himself of his fiercest rival and the East Anglian ruler to boot. It had been a salutary lesson for King Edward in the problems of command and control in the field on such a wide-ranging campaign, but it had also been a period that outlined the lengths to which competitors for the throne of the ever expanding kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons were prepared to go to prosecute their claim. For Æthelwold, however, despite the open hostility and bitter hand-to-hand fighting, he was only able to persuade perhaps just one moneyer to produce a coin for him, an issue still debated today. The sole surviving coin struck in the name of ALVVARDU may be testimony to the political failure of an Anglo-Saxon king who might have been.

900–21: The Re-Capture of the Danelaw–Grand Strategy in the Landscape

The situation across the midlands and the north of England in the early part of Edward the Elder’s reign was extremely colourful. It took almost a generation for King Edward and his redoubtable sister Æthelflæd of Mercia to re-conquer the Danish midland strongholds and gather allegiance from these communities to the king of the English. The way in which this was achieved was a matter of long-term strategy representing one of Medieval Europe’s most remarkable and sustained military come-backs. There will always be unanswered questions about how it was all done, and inevitably we are missing some important fine-grained detail.

After the Battle of the Holme and the defeat of Æthelwold King Edward appears to have struck up a treaty agreement with the Danes. Simeon of Durham records that in 906 an agreement was reached at a place called Yttingford (on the River Ousel near Leighton Buzzard). This was frontier territory between the English and Danish-controlled areas. We do not know the terms of the treaty, but Edward’s policy towards the Danes between 906 and 909 seems to take on a certain characteristic. Land in the Danish-controlled areas was being purchased from the Danes by the king and was subsequently given to Englishmen of rank. This policy was enforced from Derbyshire in the north to Bedfordshire in the south. Combining these islands of English interest into something more tangible in the landscape, however, would take systematic campaigning and strategically sensitive fortress building.

The first instance of a concerted campaign in the north took place in Northumbria. Edward brought his forces to the Danes on their doorstep in 909. It was a five-week campaign of reduction, of harrying the land. It led to a swift peace negotiation by the Danish leadership. But the next year, the men of the north were back with vengeance. They led a punitive campaign deep into the heart of English Mercia, into the patrimony of Lord Æthelred and his wife Æthelflæd. Edward was in Kent putting together a fleet for an eastern seaboard coastal campaign. The Danish raid went all the way down to the Avon near Bristol and along the banks of the Severn. Edward raised a force to take on the raiders, but we do not know how long it took him. We do know, however, that it was drawn from both Mercia and Wessex and that it is described as finally ‘overtaking’ the Danish force at Wednesfield near Tettenhall on 5 August 910. The Danes had just crossed a river and were laden with booty. The subsequent Battle of Tettenhall was a resounding victory for Edward, so much so that the leaders who perished on the Danish Northumbrian side left behind them a political vacuum as a result of their annihilation. There began a period of history where other Scandinavians, particularly those based in Ireland, would see their own opportunities in Northumbria.

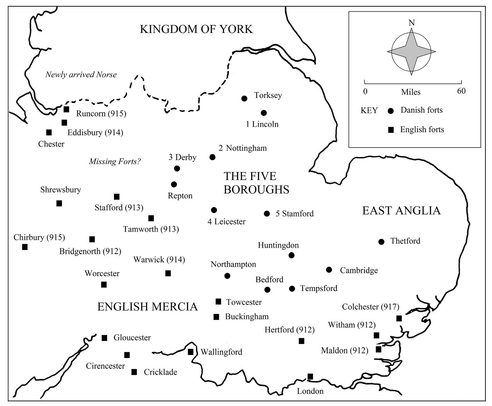

As for the Mercians, Ealdorman Æthelred had long been unwell and much of his policy making was carried out by his wife Æthelflæd. In fact, Æthelred died in 911 and Æthelflæd seems to have already begun her great fortress-building campaign in the midlands, starting with the unidentified fort of Bremesburh in 910. To this were added the forts at Scergeat and Bridgnorth (912), then Tamworth and Stafford (913), Eddisbury and Warwick (914) and Chirbury, Weardburh and Runcorn (915). Some of these forts were situated along the traditional Mercian borders with the northern kingdoms. And so by 915 the military landscape of the central and northern midlands of England represented a patchwork of estates and fortifications, each of them strategically positioned. Edward, for his part, had begun his strategic campaigning again in 911.

Edward took over London and Oxford and began to build a burh on the north bank of the Lea at Hertford placed between the rivers Maran, Beane and the Lea. In 912 he took a group of men into Essex to challenge the Danish force there. He camped at Maldon and had probably taken a naval force to support him. While there, Edward’s fortress builders set to work at Witham, building another burh on the line of the Roman road from Colchester to London, thus preventing westward advance for the enemy. The people of the countryside who were under Danish control came to the king to give him their support and seek his protection. Meanwhile, some of Edward’s men were finishing a second, more southerly burh at Hertford on the Lea, clearly designed to work in conjunction with the first to control river traffic.

The sequence of events that followed is difficult to interpret since even the entries in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle differ from each other by one or two years. However, it is clear that at some stage, perhaps in 913, two mounted forces from Danish Northampton and Leicester ‘broke the peace’ and killed many men around the Hook Norton area. Another mounted Danish force rode against Luton and was resoundingly beaten by the English thereabouts. In fact, they took their horses and weapons as a victory prize. The next year, this new English pride was put to the test by a Viking force that sailed up the Severn, raiding into Wales and Mercia as far as Archenfield. A garrison force assembled from the forts at Hereford and Gloucester was called out along with the men from ‘the nearest strongholds’ and the Vikings were driven into a place were they could not give battle. Their leader Hroald had perished in battle and his followers tried in vain to harass the north Somerset coast before leaving for Wales and then Ireland. The English under Edward were proving just as organised as they had been in the latter years of Alfred’s reign.

For Edward, it was time to return to the problems not of visiting Vikings, but of the continual threat from the Danes living in England. The king took a force to Buckingham and within four weeks his men had erected a twin fortress either side of the Ouse, thereby denying the Danes of Bedford any room for manoeuvre. The effects of Edward’s remarkable energy in fortress building were profound. This latest effort brought him a visit from Thurketyl, a leading Dane, who offered his submission to the king. Also, the men of Bedford and many of the Danes of Northampton came to him. The following year, 918, saw Edward repeat his building exercise at Bedford itself, enhancing its defence by building a twin to the existing fortification on the other side of the river.

Events are difficult to sequence after this, but it is clear that an English army took up quarters at Towcester, an old Roman fort on the River Tove. This was at the southern end of the Northampton Danes’ territory. The same force was ordered by the king to build another fort at Wigingamere, a site that is unidentified but which may well be Wigmore in Herefordshire on the Roman Road near to Offa’s Dyke. With the setting up of an English garrison at Towcester, the Danes at Leicester and Northampton took the opportunity to attack it. It was a siege that lasted all day and yet the Danes failed to break it. In the end, English reinforcements arrived and the besieging forces withdrew. There followed a punitive campaign by the Danes of the reduction of an area of land described as ‘between Burn Wood and Aylesbury’. Predatory bands took what they could in terms of men and property, capturing the population by surprise. It was a deliberate policy in that the Danes knew this area belonged to the king himself. It seems the Danish-led forces of the midlands and East Anglia were now acting if not in unison, but according to a planned grand strategy. Next, the Danes of Huntingdon and East Anglia went from their homes to build a fortress at Tempsford, a site that controlled the confluence of the Iver and Ouse. From here it would be possible to launch attacks against the areas of Bedfordshire that Edward had re-claimed in the previous years. They soon tried just this, heading for Bedford itself. However, its English garrison had out-scouted their enemy and met them in the field outside Bedford and won a victory that saw large casualties on the Danish side.

While the wars were being fought in the hotly debated areas of Bedfordshire, Æthelflæd was at work in the north of Mercia. She took Derby, the most westerly and most isolated of the Danish Five Boroughs of the north midlands, which included Leicester, Nottingham, Stamford and Lincoln. Æthelflæd is recorded as having lost four thegns dear to her at the gates of the city, but it was becoming clear that her part in a strategic pincer movement was being successfully carried out.

The next move was led by the Danish East Anglians with assistance from the Danes of Essex and other areas of the Danelaw. They headed all the way over to Wigingamere and besieged it for a day, but once again they were unsuccessful in breaking it down and turned instead to cattle rustling. It was becoming clear that Alfred’s system of fyrd rotation and the tripartite division of military burdens was working very well in the wide landscape of the midlands where everything was politically fluid.

The forces of the stronghold on the English side near to Tempsford were called out by the king and led to the new Danish fortification. Here, a successful siege was carried out and the place was broken down. It cost Jarl Toglos and his ‘king’ their lives, along with many others. Being a Danish king of East Anglia in the early tenth century was clearly not good for one’s health. All those who put up a fight were killed. Edward was on something of a roll now and headed soon to Colchester where he conducted another successful siege and broke the old Roman fortification killing many of its defenders, save those who managed to scale the old Roman walls from inside and flee. Clearly now, the march of the Anglo-Saxons was looking inexorable, particularly in what had seemed safe East Anglian Danish territory. With a hint of desperation on the part of the Danish leadership, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that at harvest time the East Anglians summoned up an army from their own bases (and from a force of Viking ‘pirates’ they had enticed to join them) and travelled to the English fortification of Maldon in Essex intent on a revenge attack. Maldon withstood the siege and was relieved by another mobile English force. If this was not enough ignominy for the Danes, they were caught and defeated by the garrison force itself in open battle.

Map 2. Forts involved in the re-conquest of Danish held territories c. 910–918.

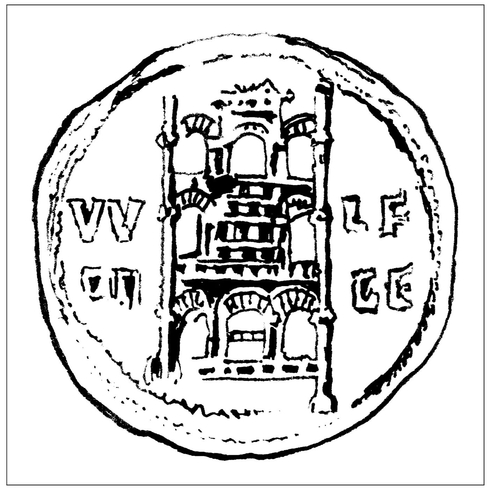

It was harvest time of the same year when Edward moved again. This time, he took an army to Passenham, which controls the point where the Roman road out of Towcester fords the road across the Tove. From here, a detachment strengthened the defences with stone walling at Towcester. It seems to have been enough to gain the submission of Jarl Thurferth and the Northampton Danes. In fact, the submission of Jarl Thurferth included an area of land as far north as the River Welland, the inhabitants of which sought Edward as their lord and protector. The tour of duty for the Passenham fyrdsmen had come to an end and they were quickly replaced by a new English army which set out to Huntington to repair its defences. More people were coming to Edward from the surrounding countryside. It was a triumph of royal organisation and military discipline. The combination of King Alfred’s fyrd rotation system and the building of strategic fortifications in the landscape across the heartlands of England was proving to be invincible. Edward would even have coins minted showing a reverse with a tower or fortification on it, much in the style of Constantine the Great’s coinage, the legendary Roman emperor (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Silver penny of Edward the Elder, Tower Type.

Some more repair work was ordered at the damaged fort of Colchester and to Edward came the people of East Anglia and Essex, some of whom had been under direct Danish rule for thirty years. The fighting men of East Anglia even agreed to ally themselves with Edward and assist him by both land and sea. The Vikings of Cambridge, a long-established force, also came to Edward. The Kingdom of the English was growing rapidly. The Anglo-Saxon king was taking control of a great part of the midlands on both sides of Watling Street. There would, however, be battles to fight with a new Norse power that had just established itself in York. However, the remaining towns of the Danish Five Boroughs, whose leaders may have had one eye on developments in York, were the next to receive Edward’s attention. Edward took an army to one of them, Stamford in Lincolnshire. Here, at a point where Rutland, Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire meet on the River Nene, Edward built a fortification on the south side of the river and the Danes in the fort on the north side submitted to him. The king then must have heard the news that his sister Æthelflæd had died while at Tamworth, having just recently peaceably taken control over Danish Leicester. He set out there with a force and seized control of the town and of all Mercia and its subject Welsh patrimonies which his sister had achieved lordship over.

Only Nottingham and Lincoln remained disloyal to Edward of the traditional Danish Five Boroughs. He went next to Nottingham where he captured the place and ordered it to be improved and occupied by both Danes and Anglo-Saxons. There is evidence that the town at this stage had an additional encircling ditch and bank built around it. Soon the Mercian frontier would be restored to what it had been in the glory days of the middle English kingdom under King Offa. Edward’s visit to Thelwall (commanding the crossing of the Mersey at Latchford) and the repair of the Roman fort at Manchester can be seen as a strengthening of Mercia’s northern territories. The focus would now shift to a battle in the next generation between the Kingdom of the English, complete with its dynamic and multi-cultural Mercia, and the Norse kingdom of York, the political and military activity of which would dominate the tenth century in the north. Before his death in 924 Edward would again visit Nottingham and had a bridge built over the Trent linking both fortifications there. From here he went to Bakewell to oversee the building of yet another fortification. His reign was marked near to its end by the submission to him of the king of the Scots, of Strathclyde and of York and the English enclave at Bamburgh in the far north. The strength of the northern leaders’ commitment to this agreement would be tested in the years to come and its meaning has been debated down the centuries. One thing is certain, however, the campaigns of Edward the Elder and his sister Æthelflæd must be regarded as the most sustained and successful in Anglo-Saxon history.

1063: Harold Godwinson in Wales–the Making of a Leader

Harold Godwinson’s rise to power in 1066 was not a matter of accident. Many writers attribute Harold’s mastery of the late Anglo-Saxon political landscape to familial ties and the respect with which he was held on the eve of Edward the Confessor’s death, even by the ailing king himself. But it has been put forward that the defining moment in Harold’s career was not in fact the assuming of the English throne in 1066, but his devastatingly effective campaigns in Wales in 1063. It was here that the reputation of the man changed from one-time rebellious member of the Godwin family to that of an effective military commander and ‘statesman’.

Harold’s opponent during his Welsh wars was Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, who began his reign in the Welsh kingdom of Gwynedd in 1039. Gruffydd was an acquirer–an expansionist warlord, ready to play all the games available to him at the expense of his Welsh neighbours and very often at the expense of the Mercian English, into whose territory he launched frequent raids. For the Welsh, however, he had soon begun to develop something of a personality cult. Gruffydd’s main target area across the border was rural Herefordshire. It is because of such raids into this marcher territory that King Edward the Confessor had entrusted the defence of it to Earl Swein Godwinson, Harold’s brother, in around 1043. Swein’s approach was to ally himself with Gruffydd and in doing so pose a problem for Gruffydd’s enemy Gruffydd ap Rhydderch of Deheubarth. The two even went on campaign together, resulting in the handing to Swein of several Welsh hostages. But on his return from this very campaign Swein took something of a personal shine to the abbess of Leominster and held her for a year. It was a serious enough crime to cost Swein his earldom and exile. Into the vacuum over the next few years stepped King Edward’s Normans, whose presence in their first marcher castles seemed not to deter Gruffydd from further raids.

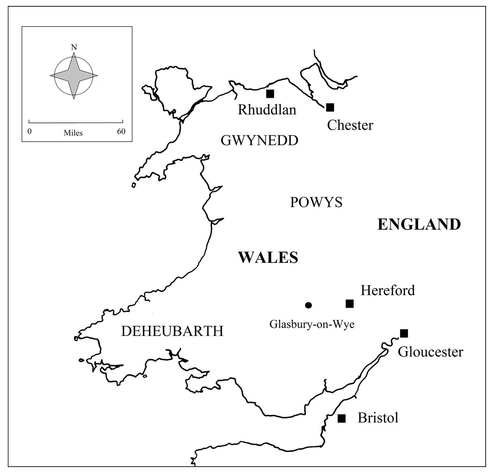

Harold, as the new earl of Wessex, became directly involved in Welsh affairs in 1055. His family had handsomely recovered from the political crisis of the early 1050s, which saw them return from exile in overwhelming force. The Godwinsons were in the ascendancy now, with Harold playing an increasingly leading role. This year saw a great turn around in the ruling of England’s earldoms, from which Harold and his brothers benefited. Ælfgar, earl of East Anglia, found himself exiled, accused by some people of treason. His response was to go to Ireland and fetch himself eighteen ships’ companies of mercenaries, and then head to Wales and into the welcoming arms of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. The two of them led their forces to Hereford where they were met by the Norman Earl Ralph, whose lack of success in getting his fyrdsmen to fight mounted is well documented but possibly misunderstood (p. 61). The subsequent allied sacking of Hereford was too much for King Edward to bear, so he sent Harold to the area. Harold had come from Gloucester with a huge force. It was enough to ensure the allies fled back into Wales for the time being. Harold then turned his attention to the town of Hereford, so pitifully mauled by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn and Ælfgar. He had built a broad, deep ditch and ‘fortified it with gates and bars’. High politics then seems to have played its part, as Harold sought peace with the allies and King Edward restored to Ælfgar his lost earldom.

In June 1056, however, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn was back again. This time he would be opposed by the local forces of the brand new Bishop Leofgar of Hereford (formerly Harold’s personal chaplain). The militant Leofgar took with him a contingent led by the shire-reeve Ælfnoth, but they got as far as Glasbury-on-Wye before both being slaughtered by the Welsh in a miserable campaign seemingly designed to recover the lost territory of Archenfield. Earls Harold and Leofric along with Bishop Ealdred came to shore up the situation. They brought with them another huge force, but once again decided to resort to diplomatic agreements with Gruffydd ap Llywelyn. The Welsh king, now recognised by Edward as ruler of all Wales, gained further territorial advances in this agreement, which included the fortification of Rhuddlan, a place where he would soon relocate his court.

After the death of the Norman Earl Ralph of Herefordshire, Harold took direct control of the region. This would be the springboard for his later operations. Ælfgar had won the earldom of Mercia after the death of his father Leofric, but, yet again, this turbulent earl found himself exiled by the king for reasons not recorded. Once more, he ran to Gruffydd ap Llywelyn who had by now married Ælfgar’s daughter, so strong was their alliance. Between them, Ælfgar and Gruffydd accompanied by a mysterious Norwegian fleet forcibly restored the Mercian earl to his patrimony. Regrettably, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes it all as ‘too tedious to tell’. It is a frustrating entry in the sense that we are unable successfully to piece together how the campaigns of 1063 came into being, suffice it to say that this time Harold Godwinson took on a distinctively offensive posture and was aided by his brother Tostig of Northumbria in a joint venture designed to rid Edward of the menace of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn for good. Tostig’s Northumbrian coastline may well have been targeted by this enigmatic Norwegian force, thus driving him into the arms of his brother for vengeance. Also, Ælfgar’s recent death may have had something to do with Gruffydd perceiving his peace with the English to be at an end. It is possible he resorted once again to raiding into English territory, finally compelling King Edward to order his destruction.

Just after Christmas in 1062 Harold led a force north-west of Gloucester and into the region around Rhuddlan. It almost achieved complete surprise and may well have been entirely mounted. The stronghold at Rhuddlan was sacked and burnt along with Welsh ships and their equipment. Gruffydd, however, just managed to sail away in time. But the destruction was widespread and had a profound effect on Welsh minds, having been directed with such daring against a citadel that many Welshmen may have thought unchallengeable from England.

Map 3. Places mentioned in Harold Godwinson’s campaigns in Wales.

With Gruffydd still alive, Harold returned to England to put together a plan with the king’s backing that would involve his brother Tostig providing one arm of a two-pronged and wide-ranging attack on Wales. Harold would sail a fleet from Bristol around the north of Wales, while Tostig would lead an entirely mounted force into Gwynedd, the home kingdom of Gruffydd. The naval force harried the coastline and killed people or took hostages wherever it went. When they went on foot Harold’s troops were especially prepared for the difficulty of the terrain by wearing much lighter body armour than normal, according to the twelfth-century writer John of Salisbury:

He [Harold] decided . . . to campaign with a light armament shod with boots, their chests protected with straps of very tough hide, carrying small round shields to ward off missiles, and using as offensive weapons javelins and a pointed sword. Thus he was able to cling to their heels as they fled and pressed them so hard that ‘foot repulsed foot and spear repulsed spear’, and the boss of one shield that of another.

At each point in the campaign the Welsh people were told to withdraw their support for Gruffydd and it seemed ultimately to have an effect. As Gruffydd withdrew into the mountains of Snowdonia, he began to lose the support of his people, who were still at the receiving end of punitive English hostility. In August 1063 Gruffydd was finally betrayed by one of his own. Cynan, son of Iago, killed the legendary Welsh king and brought his head to Harold, who subsequently took it to his own king. With Gruffydd’s half brothers Bleddyn and Rhiwallon now given joint control of North Wales by Edward and hostages and promises of tribute and service extracted, Welsh expansionism at the expense of the English was severely–and some might argue–permanently checked.

Gerald of Wales, a famous Medieval Welsh historian, tells of the measure of Harold’s success. He says that ‘erected by entitlement according to ancient tradition’, the Englishman left a trail of inscribed stones across Wales to commemorate his victories. Many he said, simply read ‘HIC FUIT VICTOR HAROLDUS’–‘Harold was the victor here’. Harold was clearly at the top of his game after the Welsh campaigns. Within two short years, however, he would face another great test as the new and controversial king of England in desperately troubling times. Had he won the Battle of Hastings in 1066, history would have spoken very differently of Harold, son of Godwin. His status would have jumped to that of a national legend. It was certainly heading that way after the Welsh campaigns. One man with a vaulting ambition far greater than that of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn would see to it that the Englishman’s reputation would collapse into a stormy sea of desperate but effective propaganda, and that man would become the first Norman king of England.

Battles

896: Alfred’s Navy in Action–the New Ships are Tested

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives us a curious account of a naval battle that took place on the south coast of England in 896. By now, Alfred’s struggles with the Danes were not exactly over, but he had proved himself to be a master of strategy on land.

The Danes had fled England after a series of brutal campaigns that saw them half starved to death by Alfred and his followers in encounters of speed and sophistication which had never left them alone in the English landscape for long. But, as the last of the enemy ships sailed off to the shores of northern Europe to terrorise the folk of Francia, there remained untested King Alfred’s naval response to the attentions of raiders on his shores.

The test came in 896 when the south coast of England had been repeatedly harassed by ships’ companies from the Danish-controlled areas of Northumbria and East Anglia. Most of the ships of the Danes, which are describes as ‘askrs’ (a Scandinavian term) in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, were still the very same vessels they had used years ago. We have seen above how the king had organised his ship-building programme, how he had studied Viking ships captured by the Londoners at Hertford and other ships taken years before. But how would the allegedly taller and faster Anglo-Saxon ships of sixty oars (twice as long as the Danes’ vessels) fare when put to the test? The new ship type was built, as we have observed, ‘as it seemed to himself [Alfred] they might be most useful’.

Six ships came to the Isle of Wight ‘and did great harm there, both in Devon and everywhere along the sea-coast’. We are not told where they had come from but the Northumbrian or East Anglian centres present the most likely source for these Danes. The king then ordered nine of his new ships ‘to go there’ and we are told that Alfred’s ships ‘got in front of them at the river mouth towards the open sea’. The Danes came out to the English with three of their six ships, while the remaining three, stood on dry land at the upper end of the river mouth–and the men were gone off up inland’. But where was this river mouth? Possible candidates for this locale have been put forward. They include the Exe Estuary in Devon (an area clearly recently attacked by the Danes) or Poole harbour in Dorset. The English ships are said to have captured two of the three ships at the entrance to the river mouth ‘and killed the men’. But one of the three ships got away. However, on this remaining ship only five Danes survived to sail their vessel away amid a sea of drowned men.

This may sound like a victory for the English ships of Alfred’s brave new navy, but more action was to come. The one Danish ship that just about escaped a mauling had managed to do so due to the fact that many of the English ships had run aground ‘very awkwardly’. Three English ships ran aground on the side of the channel that the three beached Danish ships were on, whereas what we must assume to have been the remaining six English ships ran hopelessly aground on the other side of the channel and were unable to play a part in the ensuing struggle.

So, three English ships were aground, leaning on their sides near to where the Danish beached ships had been set. The crews of the Danish ships had been inland, but either very soon returned or had left a reasonable force in those three ships, because the chronicler says they set about the crews of the stranded English ships. The difference in disposition between the Danish and English ships is implied by the chronicler. The Danes, who had beached deliberately, almost certainly will have positioned their vessels to aid a quick get-away after the tide had ebbed. The English, however, simply ran aground, hence the reference to them being on their side.

It was not a happy experience for Alfred’s sailors. Not all of them were English, either. It seems from the list of those killed in action, that Alfred had employed a good number of Frisians in his new navy. Famous for their sea-faring capabilities, the Frisians had been masters of the trade routes of the North Sea and English Channel for centuries. But here, on a bleak English shore the lives of some very high-ranking and beloved men to the king of the Anglo-Saxons perished at the hands of the Danes. Wulfheard the Frisian, Æbbe the Frisian and Æthelhere the Frisian accompanied many Englishmen in the list of the fallen to the number of sixty-two dead. But it was recorded that 120 Danes had perished as well. Two of the first three ships’ companies at the river mouth had been completely annihilated in what must have been a bloody encounter of close-quarter fighting on the decks.

Back on the beach, at the scene of what will have looked like a pyrrhic Danish victory, efforts were being made to float the Danish vessels to effect an escape. Indeed, the chronicler recounts that the tide reached the Danish ships first, implying that they were able to float away earlier than the English. It is not known how many men were left on the Danish ships, but they managed to row out to sea and headed east again from where they had come. But the effects of the raging battle around their beached vessels must have been great indeed. ‘They were so damaged that they could not row past the land of Sussex’ is the dry assertion of the quill. Two of the ships foundered on the shores of the ancient Saxon kingdom, now comfortably absorbed into the kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons. The local Sussex men found the wretched Viking shipmen on their shore and took them to their king–a long and agonising march to Winchester. Here, the king of the Anglo-Saxons heard the story of the Danish audacity–of their destruction of some of the finest men in the king’s household and ordered every one of them to be hanged.

But there was one wretched survivor of the swords and arrows of the great naval encounter. The one remaining ship of the Danes had limped back to its home in East Anglia. The Danes returned from their Wessex coastal expedition ‘very much wounded’. But had it been a success for Alfred’s new navy? Yes it had, but the cost was dear. The new ships of the English had foundered on the beach and their crews had not been able to get away as quickly as their enemy. The deeper draft of the English ships had let them down in this regard. Several of the English ships had run aground without hope of taking part in the battle. In this sense, it can be argued that the new naval arrangements in terms of ship design were a failure. But the purpose for which they were built–to out-man and out-manoeuvre the enemy–seems to have been proved a success by the emphatic victory of those first ships which intercepted the three fleeing Danish ships at the mouth of the channel. This was progress made in the truest of Anglo-Saxon styles: expensively, and at the edge of sword.

991: The Battle of Maldon–an Invitation to Disaster?

The poem The Battle of Maldon is of course extensively quoted in any work on Anglo-Saxon warfare. Without it, the record would simply show another defeat at the beginning of a series of English disasters at the dawn of the second age of Viking incursions. But with it, we are given a glimpse of the heroism of the age and find ourselves asking such searching cultural questions as to whether it really was possible in 991 for thegns to give their own lives in vengeance for the death of their lord, a seemingly idealistic and archaic concept. Another question that is often raised in respect of Maldon is why Byrhtnoth, the East Saxon ealdorman, allowed an advantageous situation to be forfeited for a level playing field. Some observations on a mixture of military necessities and political culture, as well as some obvious landscape issues, should provide the answer.

But first, who actually fought at Maldon in 991? On the English side it is certain that the army was led by Byrhtnoth, ealdorman of the East Saxons (956–91), a man of long-standing service to the region. But on the Viking side the picture is not so clear. It is probable that Swein Forkbeard of Denmark and Olaf Tryggvason led the force opposing the English. There are even dark hints that a certain Æthelric of Bocking was treacherously planning to receive Swein on his arrival on the East Saxon shore. From the king’s confirmation of Æthelric’s will comes the grave accusation in a passage that hints at how the famous king may have got his long-remembered nickname of the ‘Unready’: ‘It was many years before Æthelric died that the king was told that he [Æthelric] was in the bad plan [‘unræd’] that Swein should be received in Essex when first he came thither with a fleet.’

The Battle of Maldon came at the beginning of a new era of Scandinavian aggression in Britain. For years the Anglo-Saxon kings had been powerful enough to deter serious raiding activity and incursions. But now, after a series of small-scale opportunistic raids on various coastal settlements, there came to Folkestone in Kent a force of a size comparable with the period of the Great Heathen Army of the ninth century, if not even greater in number.

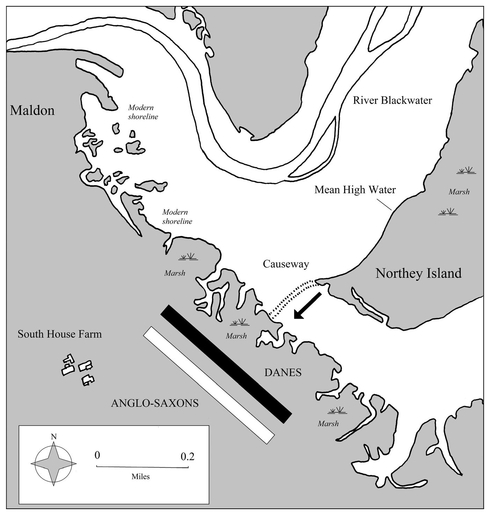

The area around Folkestone was ravaged in the summer of 991. The difference this time was that the punishment was meted out by the crews of up to ninety-three ships. From here the force went to Sandwich and from there to Ipswich. On or around 10 August 991 the force sailed to Northey Island in the estuary of the River Blackwater. They had moored opposite the burh at the heart of the East Saxon patrimony, the burh of Maldon. Byrhtnoth had to do something about it. A narrow causeway links Northey Island to the mainland outside the modern town of Maldon. There are only a few hours between high tides when it is usable, just as it was then. Here, on the mainland side, there is flat ground where the battle itself took place. From the text of the poem it seems that Byrhtnoth ordered his men to dismount and go ahead on foot, then sent their horses to the rear. He was able to bring his army up to this area thus closing off any passageway for Viking troops coming across the causeway from Northey Island. Byrhtnoth then began to drill his men in an apparently rare example of Anglo-Saxon military training. When the ealdorman finally dismounted and joined his own personal hearthtroop of warriors a Viking messenger appeared and tried to extract tribute from the Saxons in return for not bringing battle, but Byrhtnoth heroically declined the offer. He ordered his shield wall to line the shore in readiness.

The tide prevented both sides from coming at each other for some time. There then follows a curious defence of the causeway by the chosen brave Anglo-Saxon warriors Wulfstan, Ælfhere and Maccus, who when the waters had parted, slew the oncoming individual Vikings. Having observed this the Vikings chose a tactic of guile to gain the upper hand. They proposed to the ealdorman that they should be allowed to come across the causeway and form up on the mainland so that they could bring battle. Byrhtnoth is then criticised in the poem for allowing ‘too much land’ to the Vikings–an act of over-confidence it is said. A wonderful vision of Byrhtnoth marshalling his troops under skies swirling with circling ravens and the air thick with the shouts of men then follows. But why did he allow it to happen at all? We must understand where Byrhtnoth stood in the overall politics of his day. He was a regional ruler who had long service and was responsible for the defence of a large stretch of coastline. He may not have known of the sedition of others, of their desire to betray the king to the Vikings. Furthermore, he may have already had to gather his forces only recently against a similar foe at the end of the very same causeway, if a strange yet seldom quoted entry in the twelfth-century Liber Eliensis is to believed: ‘Accordingly, at one time, when the Danes landed at Maldon, and he [Byrhtnoth] heard the news, he met them with an armed force and destroyed nearly all on the bridge over the water. Only a few of them escaped and sailed to their own country to tell the tale.’ This entry is not thought to be reliable. It is followed by the return (four years later) of the same defeated Viking force to Maldon. These men goad the East Saxon ruler into another fight, which lasts a seemingly impossible fourteen days and finally results in Byrhtnoth losing his head in the final push. It also mentions Byrhtnoth’s campaigns in Northumbria and the presence of a Northumbrian hostage in the ranks of the East Saxon army, which is supported by the text of the poem. But the point is not whether the Liber Eliensis is accurate or not. It is to do with the fact that the Battle of Maldon cannot have been an isolated incident in the long history of Byrhtnoth’s defence of the shore on behalf of his lord. We are missing a whole raft of political intrigue that is barely hinted at in the sources, but which allows us tentatively to conclude that Byrhtnoth allowed the Vikings into a pitched battle because it was vital that he won it, and probably expected to do so. The Life of St Oswald, written just a few years after the battle, mentions that the Viking casualties were so many that they had only a few men to crew their ships afterwards. It all points to a deliberately chosen war of attrition, a policy that cost Byrhtnoth his life, but which may have temporarily saved his lord’s kingdom.

Map 4. The Battle of Maldon, 991.

The poem then, for what it is worth, continues with individual acts of heroism and some thumpingly good warrior antics. Byrhtnoth is soon slain. His followers, Ælfnoth and Wulfmær, also gave their lives alongside their lord, but others chose a different course. Godric had the temerity to take Byrhtnoth’s horse and flee along with others, giving the false impression that it was Byrhtnoth himself whom had fled. The poet, of course, heartily disapproves of all this. Into the fray stepped the men of the ealdorman’s hearthtroop who specifically had vowed to avenge the death of their lord or die in trying. Assisted by their Northumbrian hostage whose weaponry was limited to a bow and arrow, the comrades stepped into the battle and slew many opponents, before giving their own lives.

The poem, like so many other important Anglo-Saxon literary survivors, is incomplete and ends as the comrades are loyally fulfilling the avenging of the death of their ring-giving lord as their numbers inevitably dwindle. The heroism is of course designed for a certain audience. However, like so much in Anglo-Saxon history, it is as impossible now as it was then to divorce the ideal from the reality. This is because the values being vaunted by the poet were so deeply rooted in the psychology of the warriors of the day. Æthelred’s long and complex reign would include more military defeats and a general collapse of English morale until his son Edmund began to fight in a way perhaps echoing the heroics of Byrhtnoth and his hearthtroop in 1016. But in 991, somewhere in the region of South House Farm on the flat land opposite Northey Island to the south of Maldon, there took place a struggle that typifies all that was honourable about the Anglo-Saxon spirit.

1066: Stamford Bridge–the Secret of Surprise

Of all the campaigns in 1066, the Battle of Stamford Bridge demonstrates a good number of themes explored in this book. The importance of hostages to the leaders, the influence of terrain on the battle at a tactical level and, above all, the importance of descending upon an enemy when he is not expecting it. Another aspect of warfare is also brought out by a study of the battle. This is the question of how far a Viking army of the period can be from its reinforcements and supply before suffering the consequences of over-stretching itself.

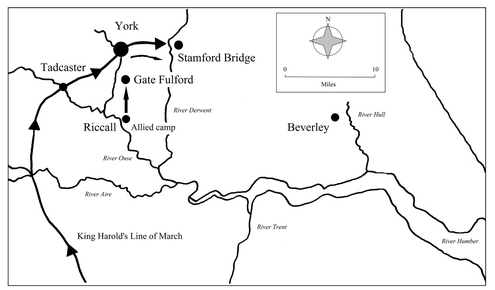

The Battle of Stamford Bridge has garnered plenty of attention over the years. Its immediate predecessor, the Battle of Fulford Gate, has received less. Nevertheless, Fulford Gate is just as important a battle. The political events leading up to the campaigns of 1066 are very well documented. Suffice it to say that on the one side was the newly crowned King Harold of England, supported locally by his new brothers-in-law Earls Edwin and Morcar, and on the other was Harold’s by now estranged brother Tostig, whose loss of his earldom of Northumbria had all but consumed him while he was in exile. Tostig had found himself an ally, a man already a legend in the Viking world. Harald Sigurdsson (later named ‘Hardraði’ or ‘ruthless’) had been in the Varangian Guard serving the Byzantine emperor and was now the Norwegian king. He was a man of extraordinary physical stature. His claim to the English throne was based on a promise made by King Harthacnut of England to King Magnus of Norway that who ever died first, the other should inherit his kingdom. It was Harthacnut who died first, but Magnus never really prosecuted his claim and so now in 1066, very much at the request of an insistent Tostig, Harold Sigurdsson of Norway sailed to the Humber Estuary with a colossal fleet of up to 500 ships. His wars with Swein Estrithson the king of Denmark were getting him nowhere, and now would be the time he would take the English throne instead.

It is probable that Sigurdsson came to England via the Orkneys where he picked up Earls Paul and Erland and probably Tostig and his Flemish mercenaries, who were by now in Scotland. Scarborough was ransacked on the journey around the coast to the south, after which the combined fleet sailed up the Humber Estuary and then up the Ouse to Riccall where they moored ready to take York. This was on or around 16 September. Edwin and Morcar sent to King Harold the news of the landing and raced to York. The brothers got to York and gave battle to the south of the city at Fulford on 20 September. They appear to have formed up along the Germany Beck, a water feature feeding into the river, pinning one of their flanks on the river itself. It was an ideal defensive position in that this was where route ways into York from the south converged. The Vikings knew they had to defeat the brothers to get to York. On the west flank nearest the river the Norwegians had most of their muscle and it was here they prevailed in the end. Earl Edwin’s forces suffered greatly as they were retreating with their backs to the river in places. Morcar’s men seem to have recoiled as far as Heslington, a mile away to the north-east. The way was open now for Harald and Tostig to take York. Edwin and Morcar, although defeated, would later play a part in the campaign, but for now the speedy response of the new king of England would bring on the next stage.

It seems that after the initial hostage exchanges, Tostig may have prevaricated at York. Northumbria after all was an earldom Tostig had recently held and there must have been room for some negotiation. A total of 150 hostages were exchanged and supplies given to the allied army. Harald and Tostig then returned to their ships at Riccall. By Sunday 24 September, King Harold had arrived at Tadcaster, 8 miles south-west of York. Here he is said to have ‘marshalled his fleet’, a possible reference to some English deserters from Tostig’s fleet who would have found themselves hemmed in by the allies at Riccall. Alternatively, it is just possible that the ships might have been crewed by the Danes sent by the king of Denmark to aid the English against Harald Sigurdsson. Nevertheless, Harold of England swept into York on Monday 25 September apparently unopposed.

King Harold quickly stifled any means of alerting his enemies to his presence. The two allied commanders Tostig and Harald were dividing their forces into those who would stay behind with the ships and those who were to go out to the junction of the roads to the east of York and meet with the expected regional leaders for hostages and tributes to be paid. They cannot have been anticipating King Harold of England to arrive so quickly. Earls Paul and Erland stayed at Riccall and Harald and Tostig travelled to claim their hostages. When the latter two got to Stamford Bridge at the junction of the regional roads, they were 11 miles from Riccall. Not only would this distance prove to be a fatal miscalculation, but according to legend the Norwegians had left their armour on shipboard, so fine was the weather.

The account given of the Battle of Stamford Bridge by the thirteenth-century historian Snorri Sturluson is shot through with anachronisms and inaccuracies. It still provides us, however, with a flavour of the subsequent battle that is difficult not to include in any modern observation of it. As the allies approached York from where they had been they saw a large cloud of dust raised by horses’ hooves. Shields and white coats of mail shone beneath the cloud. Harald Sigurdsson asked Tostig who these people might be, but Tostig was unsure. So they waited. ‘The closer the army came’, says Snorri, ‘the greater it grew, and their glittering weapons sparkled like a field of broken ice’.

There was no way Tostig could get back to the ships at Riccall as the realisation dawned upon him that the approaching force was that of his brother. He and Harald instead fell back across the Derwent over the bridge. Harald had sent three messengers to Riccall for reinforcements, but these men were several hours march away at best. It was during the falling back operation that a famous holding action is supposed to have occurred at Stamford Bridge itself. Inserted by a later hand into the Abingdon version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is the following fascinating account:

There was one of the Norwegians who withstood the English people so that they could not cross the bridge nor gain victory.

Map 5. The Battle of Stamford Bridge, 1066.

Then one Englishman shot with an arrow but it was to no avail, and then another came under the bridge and stabbed him through under the mail-coat. Then Harold, king of the English, came over the bridge, and his army along with him, and there made a great slaughter of Norwegians and Flemings . . .

Just before the full battle commenced Snorri recalls that an English horseman enquired of a man whether Earl Tostig was in the army. The earl answered the man in person. The rider told Tostig that the king of England would offer Tostig his earldom back and a third of his kingdom. But this did not impress the earl who told the rider of the damage done to him by his brother during his exile. Tostig then asked the mystery rider what his new lord, King Harald Sigurdsson, could expect from the English king. The rider’s famous answer (according to Snorri) was emphatic: ‘King Harold has already declared how much of England he is prepared to grant him: seven feet of ground, or as much more as he is taller than other men’. Tostig knew the rider all too well. Brothers cannot successfully disguise themselves from one another. When he revealed the identity of the rider to his new lord Harald, the Norwegian berated him for not alerting him sooner, but did at least admit to his men that King Harold of England, although ‘little’, sat ‘proudly in his stirrups’. The story Snorri spins is a wonderful yarn, but what happened next was very grim for those who lost their lives. There followed one of the most comprehensive annihilations in Medieval history. Upon these battle flats to the east of York would be piled the bones of thousands of warriors. They could still be seen in the twelfth century according to Ordericus Vitalis, an Anglo-Norman monk.

Snorri gives us an account of the battle but confuses what happened later at Hastings with events at Stamford Bridge. He talks of repeated English cavalry charges against the Norwegians, which although not beyond credulity, smacks of the Normans at Hastings and not the English at Stamford Bridge. He talks too of pauses in the fighting and of the death of a king (Harald) through the firing of an arrow. All we know for certain is that neither Tostig or Harald survived the Anglo-Saxon onslaught. Harald was possibly shot in the neck with an arrow. As for Tostig, William of Malmesbury says the earl was found slumped beneath his banners, capable only of being identified by a wart between his shoulder blades.

It was all too late for Eystein Orri, the leader of the Riccall relieving force. Notwithstanding their arrival with armour as well as weapons, they were exhausted when they got there. There is even the distinct possibility that Harold’s ‘marshalling of his fleet’ at Tadcaster contained an instruction to fall upon the Viking reserves at Riccall should they get a chance. If this happened it may well explain why just twenty-four ships returned to Norway out of the several hundreds that came. Just Earl Paul and Olaf, the son of Harald, led the sorry remnants home with a solemn promise not to return. The Battle of Stamford Bridge was nothing short of a masterpiece of military planning. The conqueror of the Welsh, Harold son of Godwin, had just one more enemy to defeat to be sure of a permanent grip on the throne of England.

1066: Hastings–Landscape, Locations and Evidence

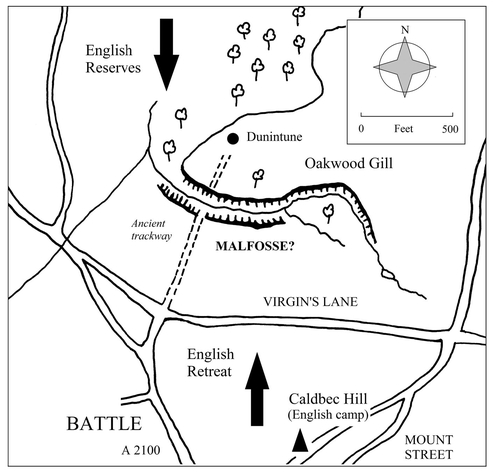

We cannot read about the Battle of Hastings and pretend we do not know the result. Such were the consequences of King Harold’s defeat on 14 October 1066 that more has been written about the battle than any other battle in English history. However, it is interesting that with so much literature at our disposal, there are questions about the battle itself that still remain. For example, where was the battle actually fought? Where was it intended to be fought? How long did it last? Was there a feigned Norman flight on the battlefield? Why did William of Normandy win it against the odds, and that most famous of all Hastings talking points–where did the ‘malfosse’ incident where many Norman horsemen met their doom take place?

As William’s remarkable invasion fleet stood out to sea on the rising tide at St Valeééry on the evening of 28 September 1066, taking advantage of long-awaited south-westerly winds, we know that he was heading for the south coast of England to claim a kingdom. However, there are disputes even about his intended landing place. William of Malmesbury tells us that the duke had told Harold ‘he would claim what was his by force of arms and come to a place where Harold supposed his footing secure’. To the west of Pevensey lay the rich Sussex estates of Harold’s family. Also, and perhaps more significantly, lay the Steyning estate seized by Harold from the monks of Feéécamp Abbey. It should not be forgotten that the Norman invasion fleet’s original starting point on the other side of the English Channel had been in the Dives Estuary, more or less directly opposite these English target areas. The Norman fleet had been blown by adverse winds to its second launching point at St Valeééry.

However, on the morning of 29 September 1066 it was at the old Roman fort of Pevensey where William set up his first temporary fortification on the western side of a salt marsh. His appearance on the south coast of England went largely unchallenged save for the unfortunate fate of some errant vessels’ crews which strayed onto the defended shore line at Romney.

The landscape around Pevensey Bay is no longer like it was in 1066. Land reclamation and drainage have vastly altered its appearance. When William landed it was a salt marsh which had once been a tidal lagoon. It was practically uncrossable and was still penetrated here and there by tidal inlets, some of which stretched almost as far inland as Ninfield and Catsfield, some 5 miles from the sea. To march from Pevensey to Hastings in 1066 involved a circuitous route. Through Standard Hill at Ninfield, then down the 7-mile ridgeway road to Hastings. It seems likely that William left an armoured reconnaissance force at Pevensey surrounded by supplies and equipment and well enough protected. Then, as is also evidenced by The Carmen, the Bayeux Tapestry and William of Poitiers, he sailed to Hastings (‘as soon as they were fit’ says the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle). Two hours after setting off at high tide he would have arrived at Coombe Haven alongside the settlement at Hastings. Here began a long road to London which stretched along the ridgeway to the north and penetrated the thickly wooded weald of Sussex. Precisely what happened to the townsfolk of Hastings is not fully recorded but we can expect their experience was not pleasant.

So, William set himself up with camp and castle at Hastings and waited. To the west of him was Coombe Haven and to the east the landscape curved around to the north from the Fairlight cliffs. To the north the Brede Estuary stretched as far as Sedlescome. William was, in effect, at the end of a peninsula. There was only one way out of this place and that was directly to the north. For Harold, who had begun his legendary race to the south, the task was to trap his Norman enemy in this bottleneck of land and smash him into the sea.

It is probable that Harold received the news of William’s landing while he was at York on or about 1 October. The king had just won a thumping victory over Harald Sigurdsson. Within two weeks he was in London. In this time 190 miles had been covered. This amounts to an average of just over 13 miles a day. Interestingly, a similar marching rate has been gleaned from the charter evidence of King Athelstan’s (924–39) campaign to Scotland in 934. Here, the king covered 130 miles between Winchester and Nottingham between 28 May and 7 June, averaging, like Harold after him, around 13 miles a day.