Humans in the path of danger

Two milestones in human history were passed during the lifespan of the Lucy project. For the first time, in 2007, more people lived in cities than on the land, and in 2011, global population passed 7 billion. Archaeology puts these tipping points into perspective. At the end of the Ice Age 11,000 years ago one estimate for the size of the world’s population is 7 million. There were no cities and people lived by fishing, gathering and hunting. They had art, ceremonies as shown by burials, and architecture that took the form of huts and villages. Their technologies included stone-tipped arrows, sickles and knives and included ground-stone bowls, mortars and pestles. A wide range of plant materials was also involved, woven into baskets and worn as clothes. The main solution to problems of fluctuating resources and hot tempers was to move, to literally walk away from the problem in the time-honoured pattern of fission and fusion still seen among today’s hunters and gatherers.

There came a time when this would not work, because of a thousandfold increase in population as a result of a revolution – the agricultural revolution. Archaeologists have long debated its origins, but how it came to be does not really affect our social brain arguments. The essence is that as food producers humans were able to sustain vastly greater populations. From about 11,000 years ago agricultural populations increased, and hunters and gatherers were on the wane.

When population was small and mobile the occurrence of natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions had little impact. This happened 12,900 years ago when one of the Rhineland volcanoes, the Laacher See, experienced a major eruption. Leading volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer describes the impact in Eruptions that Shook the World (2011). The plume peaked at heights of 35 km (22 msiles) and the crater formed measures 2 km (over 1 mile) across. Ash fallout covered up to 300,000 sq. km (115,000 sq. miles) and due to the wind direction the plume stretched from central France to northern Italy and from southern Sweden to Poland. In the immediate vicinity of the crater are huge deposits of pumice that are mined today for building material. But, for all this devastation, there seems little evidence that human populations in the region suffered a major setback that led to desertion and extinction. They would have been able to move away from the area and, by calling on networks of social ties spread over the wider unaffected region, re-establish themselves. They resettled the worst-affected area within a few generations, which on an archaeological timescale looks instantaneous. The ability to move drew on the long-standing human traits of walking and having a social brain that deals with friends and strangers by establishing kin and sharing culture.

It was to be ‘all change’ for this state of affairs in the next 11,000 years. The option to move was increasingly restricted by the reliance on fields and flocks and the investment in towns, cities and the apparatus of political power. In January 2012 the Daily Mail, one of Britain’s leading tabloid newspapers, ran a story about the Laacher See under the headline ‘Is a supervolcano just 390 miles from London about to erupt?’ Their scientific evidence was no more than an eruption is ‘overdue’, whatever that might mean. But suppose their scaremongering was right and that this time the wind was blowing from the east. Then the worst fears that tabloid Britain entertains about Europe would be realized: agriculture would be devastated, cities buried, transport brought to a halt (as air travel was in 2010 when a tiny ash cloud from Iceland covered the continent) and civil unrest guaranteed as people try to cope without smartphones.

A global population of 7 billion, concentrated in cities, courts disaster on a daily basis. Earthquakes and tsunamis have always been a feature of hominin evolution. But their potential impact has never been greater because of the numbers of people who now live in their path or beneath their smoking cones. If it really concerned us, we would relocate populations in danger to somewhere safer. But of course we can’t, preferring to wait it out and deal with the consequences when they arise.

The home straight

What does this dance with danger tell us about one of the questions we posed in Chapter 1: will it ever be possible to say when hominin brains became human minds? This should be a question for philosophers, except they have little interest in the deep-time histories we have tackled in this book. What can we add to the picture?

We briefly explored different models of the mind in ‘Types of mind’ in Chapter 4, contrasting the rational mind that solves problems with the relational one that works by building associations through the application of common social skills. Rationalism was one of the achievements of the European Enlightenment, while another was the rediscovery and excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum. These sites show in graphic detail what a comparatively small eruption can do to two small towns. If the rational mind was a sign of the modern mind then surely, following these discoveries, Naples would have been downsized to a small fishing village to avert future disaster. Although we visit the sites and their museums and flock to exhibitions about their destruction, our rational minds do not lead us to the obvious conclusion – don’t build here. Instead we are wedded to such dangerous places through family, social, economic and historical ties. Using our advanced theory of mind, many trust in religion to keep the firestorm at bay.

In our view the long trajectory, which eventually gives rise to the human mind that philosophers can pronounce on, principally involves the development of increasingly sophisticated social skills and a parallel increase in the size of social communities. As we have shown throughout this book, these skills are very ancient. They are not the sole prerogative of the 7 million Homo sapiens at the end of the Ice Age or the 7 billion living today. To a greater or lesser extent they are shared with earlier large-brained hominins such as Homo heidelbergensis and Homo neanderthalensis. They include the ability for mentalizing, to sympathize and empathize with others and to have an advanced theory of mind that allows access to another person’s intentions; these are deeply buried in our ancestry and, as we have shown, can be traced back into our primate past. Several of them involve language and the use of objects in both symbolic and metaphorical ways. As a result there is no artifact or fossil ancestor that allows us to say categorically, ‘This one had a modern mind, but that one didn’t.’ That is partly because we knew from the outset of the social brain project that coming up with a definition of a modern mind was a search for fool’s gold. What we have done instead is present the mind as a set of social skills that throughout our evolutionary history was under constant selection. From our perspective these peaked with social communities of 150 and the cognitive abilities an individual required to manage such numbers. Dunbar’s number of 150 has proved an immensely solid building block to create ever bigger and more elaborate buildings – which we have described with many examples using the term amplification. We have gone from 7 million to 7 billion in a few ‘minutes’ of our evolutionary history, and yet the core cognitive structure that regulates our social lives has remained the same, even though we have gone from the Stone Age to the Digital Age. What we have seen in this helter-skelter ride since the end of the Ice Age is the unleashing of human imagination to turn materials into novel forms of incredible variety and unprecedented quantities. But the minds behind this variety are essentially the same in terms of forging relations with others and solving the problems that all our ancestors have faced in making their way in the social world.

The social brain restated

The essence of our position is that for the last 11,000 years humans have lived in a brave new world of huge numbers, equipped only with the social skills and framework allowed by a far older biology. At its core the social brain is about group size. Social cognition is expensive. Where the ecology favours larger groups, there is a ‘strain on the brain’ – what we refer to as cognitive load. Over the course of 2 million years, evolution favoured ever larger brains in the genus Homo. The shift was a gradual response to evolutionary pressures. When humans then made sudden cultural and technological breakthroughs with enormous consequences, such as agriculture, the situation was different, and we could not respond to far larger societies with another spurt of brain growth. Rather, life was the art of the possible. In the larger societies you could not know everyone. Previously groups would split when they became too large, but that option was now far harder. However, there would also be incentives for getting on with other groups. Ancient warfare is readily apparent, and in games played for high stakes, alliances between groups must have been crucial.

Much of the last 11,000 years has been about learning how to make the large numbers work, through using the old small numbers. Dunbar’s number is still the constraint on the number of people that we can know and deal with. Most of the time we still live with small core groups of five, support groups of around 15, and band-size numbers of around 50. At the larger numbers, new responses were needed and we will look at three – religion, leadership and warfare. But first an archaeological surprise to give them some context.

The buried circles

Near the city of Urfa in southern Turkey is one of the most remarkable archaeological discoveries of the last 20 years. At Göbekli Tepe (the ‘pot-bellied hill’) archaeologist Klaus Schmidt and his international team have uncovered stone circles dating to 11,000 years ago (see Figure 7.1). These were built by people without domestic animals or crops and no pottery. Their living quarters have not yet been discovered. They were hunters and gatherers, yet they produced monumental architecture, giant T-shaped blocks up to 7 m (23 ft) tall – a sophisticated version of Stonehenge but 8000 years older – covered in carvings of animals including foxes, spiders and ducks. The pillars represent humans, as shown by the carved arms and hands on their sides. The multiple stone circles were then deliberately buried, creating the distinctive shape of the hill.

Göbekli Tepe challenges many archaeological stories. Two in particular come to mind in the context of the social brain. The first is the assumption that monumental architecture only appears with a settled life based on domestic animals and crops. And second, that to organize building works on this scale would need someone to lead the project: a man, inevitably, of vision and charisma not dissimilar to the popular image of an archaeologist running a major excavation in Greece or the Near East.

Figure 7.1: The amazing stone circles of Göbekli Tepe are 11,000 years old, predating the origins of agriculture and so provoking new thinking about the beginnings of complex societies.

Linking up

Göbekli Tepe has forced archaeologists to think again about one of their favourite histories, the power of farming to change all aspects of society. But what are the wider implications of this remarkable site? What happened to our social brains with the appearance of farming? Did we evolve rapidly a new type of brain better able to process symbols that made living in villages and towns possible? This is the view of archaeologist Colin Renfrew who, in his book Prehistory: Making of the Modern Mind (2007), is impressed by the volume of new artifacts, artistic styles and architecture that arrives with the Neolithic revolution. These new things led, in his opinion, to a fundamentally different way of conceiving of other people and the world. For Renfrew it was a sedentary revolution, based on farming, which allowed people to engage with their material culture in ways not previously possible. This was the birth of the modern mind.

We are not so sure. The social brain of a hunter living 20,000 years ago in the wide-open spaces of the Near East does not seem to us to be necessarily any different from that of someone in the cramped quarters of Çatalhöyük, a Neolithic town of 8000 people in Turkey, first occupied in 7500 BC. Certainly there was a huge change in the types and variety of material things made by these hunters and farmers. But the stone circles at Göbekli Tepe, much older still and built by people without farming, challenges the traditional view of archaeologists that only by settling down and growing crops could advances in symbolic life be made.

When it comes to thinking big, the material worlds of those first farmers in the Near East certainly stand out. But we want to know if their social worlds were still underpinned by cognitive frameworks with a much older ancestry. Our analogy would be that the 21st-century mind is very different from the medieval mind; for example, science has replaced alchemy. But although the principles on which these two cultural worlds were based seem very different, we still expect that the cognitive building blocks by which people linked up in groups and communities remained similar.

Fiona Coward tested these assumptions during the Lucy project. She took the Near East as her region and examined the cultural inventories from no fewer than 591 archaeological sites dated to between 21,000 and 6000 BC. This huge sample spanned the change in climate from the cold of the Ice Age to the warmth of the Holocene. It also saw the transition from hunter to farmer. As a result population increased and people started to settle down. Was this the birth of the modern mind as Renfrew and others claim?

Coward’s interest lay in examining social networks during this climatic and economic transition. She did this with a simple proposition: that networks can be traced through material remains. We have seen in earlier chapters how raw materials linked mobile peoples over large distances. Coward’s database took this study of social ties using material culture to another level by cross-referencing many different types of artifacts. What this meant in practice was comparing the inventories of nearly 600 sites across the Near East in 15 time-slices of 1000 years each. Sites were socially tied together by the similarity of what they contained. Different varieties of material culture were tabulated: art, burial data, architecture and other built features, ground stone, hearths, chipped stone tools, ochre, ornaments and jewelry, shells and worked bone. These produced a matrix of relationships for each time-slice which measured the strength of the material ties between the people who lived at particular sites.

What did she find? After 13,000 BC, the network ties in the Near East started to centralize, with a small number of sites in the network becoming richer in material objects than others. This is to be expected as climates changed and the earliest examples of settling down are found. The networks of the first farmers were also more far flung than the earlier hunters, extending well beyond the distances the latter achieved with the movement of raw materials. The strength of ties between sites increased over time as a result of the sheer volume of new things that were now made on a regular basis. But interestingly this is not matched when the proportion of the links that could have been made is calculated. This proportion is described as the density of the network. Here the figure actually declined over time.

Archaeologists have always been impressed by the explosion in material culture during the Neolithic, so much so they called it a revolution. Some even see this as the moment that minds became modern. But they did this without thinking about the social networks which required such stuff and the cognitive abilities that underpinned its use. The explosion of material in the Neolithic, which we do not deny, does not however signal the arrival of the modern mind. Coward’s study using a social brain perspective showed that an alternative was more likely, one that involved the amplification of an existing cognitive framework. Instead of a new, Neolithic, mind we find evidence for continuity of a common social brain.

The conclusion Coward draws is that material culture itself was the catalyst to thinking big. Hunters and farmers were after all the same human species: Homo sapiens. They may have seen the world differently, in the same way that the world-view of a medieval alchemist differed from that of a modern scientist. But when it came to building networks of contacts they used the same framework that had evolved to cope with the problems of too-little-time-in-the-day and the extra cognitive load if people are to be dealt with not as ciphers but in a socially meaningful way. The networks of artifacts, which so impress archaeologists comparing the Neolithic to the Palaeolithic, were a classic way of offloading the cost from the cognitive realm to the material world. The earliest hominins, with their smaller communities, simple stone tools, and not much else, started this path to complexity. What we see in the critical period from 21,000 to 6000 BC is an amplification of the materials that bind people together. By the end of this period, they were enmeshed in webs of culture, like Gulliver tied down by the ropes of the Lilliputians. The tiers of the social brain, such as Dunbar’s number of 150, remained the same, but what was now possible, thanks to farming, was unimaginable growth in terms of the size of the population that now used this common cognitive framework for social interaction. Society had become truly complex, in ways that outdistanced those of the hunter and gatherer, especially in the numbers game, but social life was still based on some basic cognitive principles buried deep in our ancestry.

The power of charisma: religion, leadership and warfare

Were the monuments of Göbekli Tepe possible without a leader to organize the work? This would have been someone to direct the design, quarrying, carving and erection, not to mention the labour of backfilling the site. Just one of the circular enclosures needed 500 cu. m (17,500 cu. ft) of debris to cover it up. People had to buy into this grand design and the benefits for them are obscure to us, especially because the labour force lived by hunting and gathering. If they were farmers, archaeologists would be much less surprised by the monuments, which tells us a good deal about ourselves and the way we think about the past.

Does religion supply a motive and a possible explanation? Some of the very earliest evidence for more organized forms of religion comes from the Levantine settlements of the Neolithic period dating to around 8000 years ago, where some buildings have been interpreted as ritual sites – though later, more cautious archaeologists have shied away from over-interpreting the functions of these buildings. We are on decidedly firmer ground, however, by the subsequent Bronze Age (beginning around 5000 years ago), when the evidence for ritual sites and religious artifacts is considerably less controversial. We can speculate though, that since these can only exist once the conceptual apparatus needed to create them is in place, it is likely that the religions themselves as conceptual and ritual phenomena have much deeper roots.

Given the role of organized religion in coercing populations to toe the communal line, the most plausible explanation for the rise of these kinds of religion is the social and psychological stress imposed by large communities. If settled life is to survive, two problems need to be solved. The first is to dissipate the stresses of living in close proximity, where escape is difficult because the hunter’s solution of walking away is far from easy. The second is to manage and control the activities of those looking for a ‘free ride’. The activities of free-riders, getting something for nothing, threaten to undermine the communal contract on which large-scale village life necessarily depends.

Whether agriculture was a solution to an ecological problem or an accidental discovery that opened up novel opportunities is not an immediate issue for us. Our concern here is with the fact that living in settlements created new tensions that might have prevented the subsequent development of modern human life as we know it with all its cultural ramifications. Had humans not been able to find solutions to social constraints, the modern world would never have happened.

One feature that probably became of particular importance was the phenomenon of charismatic leaders, a topic that has been of particular interest to our collaborator Mark van Vugt (see his book, co-authored with Anjana Ahuja, Selected: Why Some People Lead, Why Others Follow, and Why It Matters, 2010). Although hunter-gatherer societies eschew any social distinctions (everyone is equal), charismatic leaders have come to play an especially important role in all post-Neolithic societies and in the doctrinal religions that these gave rise to. At one level, they provide leadership; at another, they provide a focus around which the community can gather.

At community sizes of 150, where everyone knows everyone else, leaders are probably unnecessary in the sense that, with only around 20 or 25 adult males in the group, arriving at a consensus on what to do is inevitably a great deal easier than in a community of 1500 individuals with ten times as many adult males. What exacerbates the situation in such large groups is the inevitable differentials among the males in terms of age, skills, experience and reputation – criteria on which males compete and which create rivalries. Too many males, and the risk of fractiousness and fragmentation increases because too many of them are of approximately equal standing. In such situations charismatic leaders provide a natural focus around which everyone can gather and sign up to whatever particular masthead the leader happens to espouse.

Charismatic leaders play a particularly important role in religion. Most of the doctrinal religions were founded by a single charismatic leader, from Zoroaster to Gautama Buddha and Jesus Christ to the Prophet Mohammed. Each of today’s major religions began life as a minority sect of some predecessor religion. In fact, it is one of the features of religions that they seem to have a natural propensity to spawn sects. In most cases, these begin on a very small scale, but their survival ultimately depends on how quickly they can attract committed members. It is a feature of religious belief that it can rouse intense emotional commitment irrespective of the actual beliefs to which people sign up. It is as though the spirit world has a peculiar emotional hold over the human mind.

The skills that allow some individuals (usually men, but not always – think Joan of Arc) to become charismatic leaders continued to play an important role in the secular (i.e. political) world as the forces unleashed in the Neolithic revolution gradually gave rise to increasingly large political units over the ensuing millennia. By 3000 BC, city states had kings and viziers. Such people continue to contribute to the success of secular organizations of many different kinds, from businesses to schools to hospitals to charities.

Charismatic leaders become important in the context of super-large communities because they allow the group to impose some discipline on itself, to cut through the different levels of its huge numbers. Having a leader to coordinate and manage community behaviour has obvious advantages. But it comes at a cost since every individual has slightly different interests, and, in the end, an individual that emerges as a leader will always pursue the strategies that are more in line with his or her interests than anyone else’s – not least because it is inevitable that everyone in the community will have slightly different views about the best thing to do. A charismatic leader who can persuade everyone else to act in concert, despite what each of them might prefer to do individually, might be beneficial in the long run if the net benefits of doing so exceed those that derive from everyone acting in their own personal interests.

Protection against marauders has been proposed as a major factor selecting for a steady increase in the size of polities (political units or societies), which is observable from the Neolithic onwards. Sociologist Alan Johnson and archaeologist Timothy Earle explicitly argued for this in their seminal book The Evolution of Human Societies: From Foraging Group to Agrarian State (1987). In their view, and that of an increasing number of evolutionary social scientists, warfare has been the principal driver of the ever larger settlements (villages, towns, cities, city states) that developed historically over the 7000–8000 years following the first villages. Raiding itself is a form of free-riding – gaining at someone else’s expense. Why work, when for a very modest expenditure of energy and a small risk you can acquire all your needs from the products of others’ toil? Defence against raiding becomes increasingly necessary as the advantages (and hence temptations) of this kind of free-riding increase. And organized military units with a clear line of command and organized direction are invariably more successful than ragtag armies that lack coordination. The charismatic leader comes into his or her own in just this kind of context.

In one sense, the rise of charismatic leaders takes us over the boundary of deep-history into history, and so beyond the main concerns of this book. Our point, however, is that the seeds of much that happened between the Neolithic and the modern day owe their origins to attempts to circumvent the stresses and strains created when humans first began to live in large settlements. Secular charismatic leaders, with their trappings of status such as bodyguards and conspicuous display, are similar to religious leaders with their priests, rites and ritual spaces. Both seek to coerce their followers to toe the communal line in order to make a more effective collaboration. Such collaborations are intrinsically unstable, because the communal line never suits everyone equally – some always imagine that they pay a disproportionate share of the common effort and eventually feel sufficiently aggrieved or empowered to revolt.

Just as religions constantly fragment into new sects built around charismatic leaders, so polities collapse in factional rivalry and revolution in the same way. As a species our solutions to the problems posed by the economic changes of the Neolithic are at best imperfect, mostly because the psychology we use to solve them is the psychology of mobile hunter-gatherers living in their dispersed communities, as our ancestors did for the previous 7 million years.

Picking and choosing

Powerful factors such as charismatic leadership and organized religion have played a large part in assisting the expansion of humanity. But there are other ‘old’ characteristics that also have helped to organize the new large societies. The numbers that we can deal with individually, as we have seen, do not change. ‘Dunbar’s number’ is as much a reality for us as for the people of 100,000 years ago. What we have learnt to do is have selective personal networks. Two chimpanzees will have almost identical networks in their community – everyone knows everyone else. But in our world, we probably know most of the same people in the village or the street, and yet have completely different networks at work, in sports or in our hobbies. We switch selectively with ease.

The trades and hierarchies noted by Gordon Childe in the Neolithic hint at the origins of this switching. Merchants would want and need to deal with other merchants, perhaps hundreds of miles from home. Potters and metalworkers would want to discuss techniques with others who had the same skills. Leaders deal with leaders: when William the Conqueror divided England between 180 of his followers, he was following the principles of the social brain in brutal simplicity.

Charismatic leadership, religion and selective networks remain powerful forces whose deep-history we do not fully understand, as Göbekli Tepe shows. What we emphasize is that archaeology allows us to see the great sweep of human history often in close-up detail. Nobody who has seen an ancient city mound, a pyramid or the megalithic avenues of Carnac can fail to marvel at this tangible evidence of immense past social efforts. Whether collaborations of equals, or ventures collaboratively driven from the top, these collective monuments show how people regularly came together in numbers far exceeding their ancestors. These societies worked because their ‘old’ brains could deal with the new scale of social life. The selective hierarchical networks provided a framework for the growth of institutions and polities. At this point, the baton of documentation passes from archaeology to written history, sociology and psychology.

The technology of distributed minds: writing and texting

Fiona Coward, in her study of the networks of things in the Near East, makes the point that objects provided a framework for thinking big and then bigger. This is a good example of a distributed mind (see ‘Types of mind’ in Chapter 4) amplifying technology to meet new challenges, which in this case meant numbers of people. Before this explosion in things, we argued in Chapter 5 that language filled the grooming gap as brains and communities increased in size. Two further technologies have filled similar gaps, but this time to help organize and coordinate the huge populations of the last 11,000 years. These are writing and texting.

We would suggest that writing arose as a mechanism to ease the pressures of living in larger societies. Formal notation allowed commands to be sent, niceties of diplomacy to be shared and the accounts to be done. It was also the extension of communication that allowed formal institutions to come into being. In medieval times, St Francis of Assisi, an archetypal charismatic leader, cared nothing for property or organization. But the Catholic Church that he dealt with insisted on imposing some administrative control and the key to that was a written record.

Writing, indeed, has been the guarantor of historical continuity through the last 5000 years. We know the Chinese, Greeks and Romans far better than any other peoples of their age on account of their written records, which often detail their own struggles with organization and administration. The other great aids to social cohesion are improvements in communication and technology. The two come together in the archaeological evidence in a ship that sank at Sinan off the southern coast of Korea in AD 1323. On its way along the silk route from China to Japan, the ship was carrying thousands of ceramic pieces. The preserved goods, invoices and labels speak of merchants on their way from China to Japan, as well as monks making other journeys. Myriad other details are preserved for us throughout the last few thousand years, but few are as compelling as those that archaeology has recovered from time capsules such as Sinan, Pompeii and Herculaneum or Henry VIII’s flagship the Mary Rose, and all give tantalizing glimpses into networks of the past.

Writing also made possible the Digital Age. And like writing, the arrival of the Internet has offered us the prospect of greatly widening our social circles. Indeed, this is exactly what the founders of many social networking sites initially promised. But has the promissory note on the tin can proved true? The answer seems to be a resounding ‘no’. Despite the opportunity to create new connections at the click of a ‘friending’ button, in fact most people’s Facebook pages list only between 100 and 250 names, as one study of 1 million Facebook pages recently revealed. In one of our studies, Tom Pollet and Sam Roberts asked whether regular Facebook users had larger social networks than casual Facebook users. They did not. Two other online studies that looked at message exchanges within email and Twitter communities also found that they too were typically between 100 and 200 people in size.

It seems that we cannot radically increase the number of relationships we have, even when technology would appear to allow it. The constraint on what we do is not time or our memory for the events in which we or our friends have been involved, but rather the limited space we have in our minds for friends. But there is another reason why the Internet won’t allow us to have more, or more complex, social networks, and this is the fact that we don’t find building new relationships via text-based media very satisfying. In a study carried out by Tatiana Vlahovic and Sam Roberts, subjects were asked to rate their satisfaction with interactions with their five best friends over a two-week period. Face-to-face interactions and those using Skype were rated as much more satisfying than interactions with the same friends via the phone, texting, instant messaging or social networking sites. In part, this was because these other media are slow and clunky – the reply to a witty comment, if it comes at all, follows an unavoidable delay. By the time it comes, the excitement of the exchange has faded. Skype seems to win out because it creates a sense of being in the same room together, a sense of co-presence. And that means the pace of the exchange is much faster than it can ever be in text-based media: I see the smile already breaking on your face as I tell my joke. This is such a powerful effect that jokes we would find hilarious in the pub fall flat in an email. In addition, like face-to-face encounters, Skype is channel-rich (we hear and see), allowing communication redundancy.

What the digital world and the billions of people it now connects has done is amplify existing technologies of communication. One example will suffice: the number of words. In 1950 world population stood at 2.5 billion and the number of words in the English language numbered half a million. Some 50 years later, as Google NGRAM shows us, the number of words has grown to over 1 million, or 8000 new words a year. Over the same period population grew even faster to reach almost 7 billion. Word growth was powered by population growth and amplified by the possibilities of HTML, which was invented by Tim Berners-Lee in 1993. A combination of massive populations and a new technology cranked up, through the ancient process of amplification, the number of words we now use to connect us across our myriad social communities. The same has happened for images but at the moment, rather like archaeological objects, these cannot be so easily measured as words. One inevitable consequence of this will be the fragmentation of English into several new languages, because each person, and each community of interacting people, can cope with only a limited vocabulary (around 60,000 words) that they know and use regularly.

There is something else that is lacking in the digital world, and that is touch. Touch is a genuinely important part of our social world, even with strangers. All that fingertip grooming from our primate heritage is still very much with us. How we touch someone can say more about what we really mean than any words that we might utter. Words are slippery things: given the right emphasis, intonation or accompanying gesture, a sentence can mean exactly the opposite of what its words seem to say. So far, no one has cracked the problem of virtual touch, but if and when they do, it might represent a major advance in our ability to create super-large, well-bonded communities on the Internet.

Twitter has, of course, been a novel feature in the digital world and many have hailed it as a great democratizing innovation. Now we can create flash mobs and mass protests at a keystroke. In one sense, it is true: Twitter played a seminal role in coordinating the Arab Spring uprisings. But Twitter doesn’t create relationships – it is more like a lighthouse flashing away in the dark, irrespective of whether there is a ship out there to see it. Those who have studied this phenomenon are clear that what lay at the root of the Arab Spring was not Twitter as such, but actual face-to-face networks between a small number of charismatic leaders who set the whole thing in motion. Twitter will allow us to coordinate a gathering at a particular place and time, but not a social or political movement. Like cultural icons, these arise from personal relationships between leaders and followers, and this has been the pattern throughout our history.

Epilogue: thinking big

With our backgrounds in evolutionary psychology and archaeology, our privilege, as authors of this book, is that we can stand back and take the long view. We can indulge in thinking big. We can see in the huge diversity of modern human behaviour ancient patterns that recur. The growth in size of the human brain through 2 million years is a response to pressures that were certainly social, and that operated within our species rather than in direct relation to the external world. This growth in brain size correlates with an increase in size of human groups – the observation that stands at the heart of the social brain idea, but far from the whole story. The correlation with brain size is bound to be approximate. The human physique is now less rugged than it was 30,000 years ago during the last Ice Age, and today we have slightly smaller brains. But all modern humans share a size and structure of brain that gives them common capabilities, and also makes them operate with common constraints. What really matter in our everyday lives are the things that have always mattered since the very dawn of time, the circumstances of our births and growing up, the friendships we make and the opportunities that we take.

We asked at the beginning of this book, ‘When did hominin brains become human minds?’ There is a catch in the question that we can trace back to Linnaeus’ first labelling of our species as Homo sapiens – the ‘clever humans’. Homo the genus appears more than 2 million years ago. We should probably refer to those ancestors as humans, rather than separating them from us with rather mystic names such as ‘archaics’. If our own species name sapiens is given on biological grounds, then genetics places it after the division from Neanderthal ancestors, and the skeletal evidence puts it somewhere in Africa about 200,000 years ago. If we ask whether we would invite the people of Herto (among the earliest anatomically modern humans) round to dinner, we have to admit how artificial such questions become. Even in the present day, modern human culture allows such diversity that the modern Western reader could not easily feel comfortable with the rigours of life among the Yanomamo of Brazil or even pastoralists on the Eurasian steppe. When the people from small-scale societies are plucked out into larger ones, they too feel confusion – as did the native British prince Caractacus, who, dragged in chains to Rome in the 1st century AD, declared to his captors, ‘You who have this [Rome with its grand buildings]… why do you come to our poor hovels?’ These differences do not undercut the fundamental unity of cultural capability in all living humans. If we return to the Herto question, they too must be with us. The diaspora of modern humans is traceable back to common roots less than 200,000 years ago, and in a sense we are all cousins, if very distant cousins. The 200,000-year expanding cone represents humanity in the fullest sense.

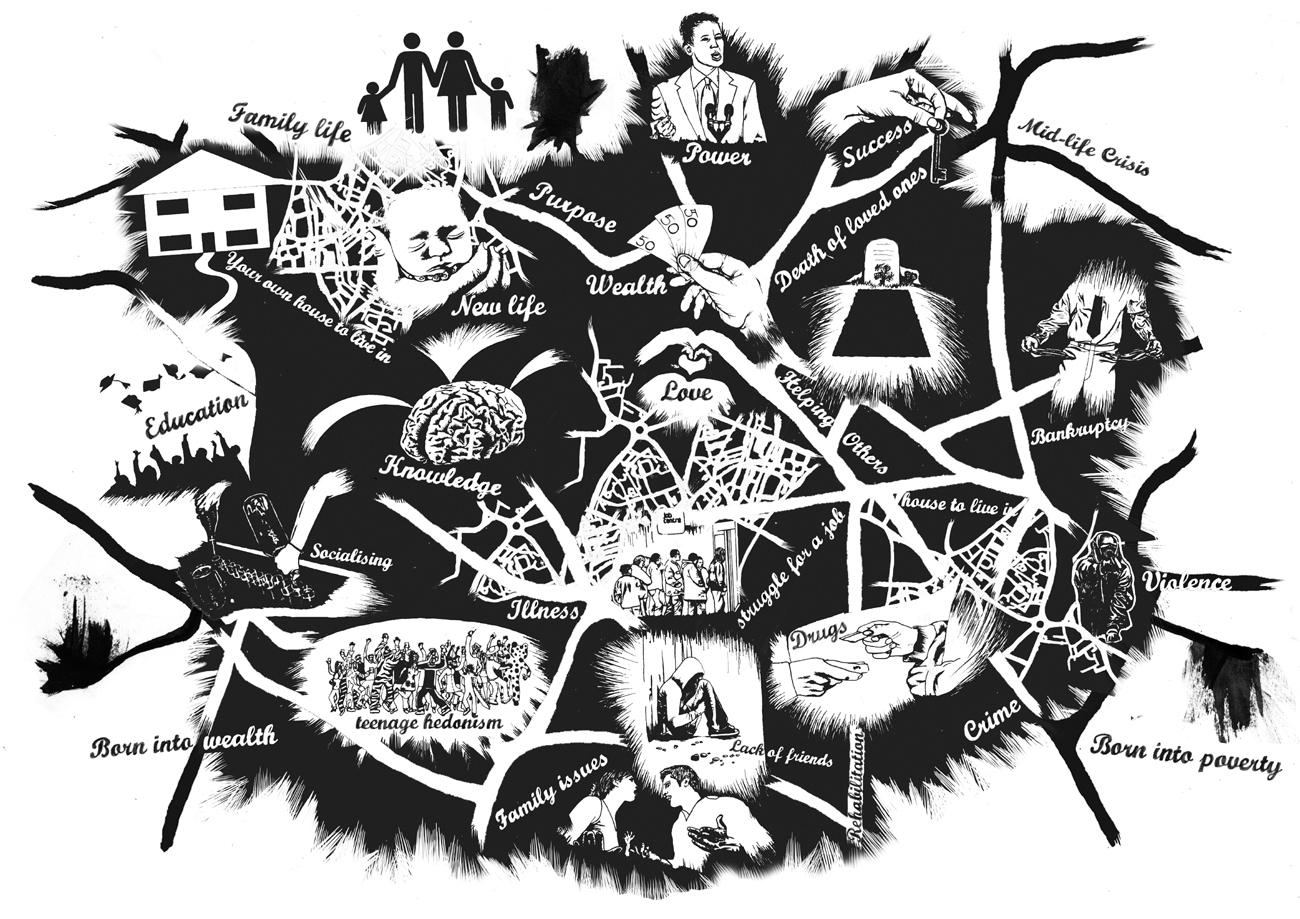

Figure 7.2: The scale and complexity of modern life requires a new selectivity in the operation of the social brain: individuals use old network principles to chart their pathways through life.

Can the social brain help resolve the next big paradox – that these modern humans did relatively little that was modern for their first 100,000 years? Even were we to subscribe fully to a modern ‘human revolution’ 50,000 years ago – which in this book we have not done – there is a further 40,000 years and more before humans scale up to farming, villages, cities and civilization. The social brain helps us to see that this scaling up was only possible because humans had already acquired the orders of intentionality, the language, the means of bonding, that would allow them to live in larger societies. Farming, however it began, would inevitably generate the larger numbers. From then on, operation of the organizational principles outlined in these pages became inevitable in the species that we call Homo sapiens.

A dramatic contemporary example of the forces for change is the Internet. Only a very small number of people foresaw its potential power (and no-one could have foreseen all its consequences). At one level, the Internet represents a human behaviour-changing phenomenon on a world- and even species-wide scale, all delivered in one generation since 1993. As individual citizens, we are free to ignore this electronic revolution, but that is becoming less and less possible day by day. It pervades our lives, from the home to the workplace, from the beach to the restaurant.

At another level, however, the social networks we have been discussing in this book still seem to rule. Internet giants such as Facebook and Twitter depend for their success on the human desire for social contact and networking. And in the political sphere, those who represent governments in a sense ‘personify’ them – making them personal. Meetings such as the G8 or G20 are the tip of this iceberg. It is interesting to note that there are around 200 countries in the world (within the natural range of variation around Dunbar’s number), but running down the scale, the top 12 of them, and to a lesser extent the top 36, have by far the biggest say. They are networked by their heads of state, but also by conclaves of ministers and officials who have their own select networks. The world functions because of this networking. Part of what we can show by studying the deep-history of the social brain is that networking exists necessarily on certain scales and with certain intensities. It works now only because of the past, shaped by the fireside, in the hunt and on the grasslands where we evolved. Social networking captures the techno-chic of the moment, that ‘Vorsprung durch Technik’. But for all its glitz as the latest new technology to bind, bond and communicate, the principles it enshrines originated deep in our evolutionary past.