L. L. Shreve, first president of the L & N, from September 27, 1851, to October 2, 1854.

From its beginning Louisville was a city destined to prosper or perish on its commerce. Founded in 1779, the town scarcely exceeded a settlement for several decades; in 1800 it counted only 359 inhabitants. Even so, Congress recognized its potential enough to designate it a port of entry in 1799, the only such port not located on the Atlantic seaboard. The title meant very little at the time, for Louisville lacked that most necessary requisite for commerce: transportation facilities. Two possible arteries reached southward into the interior: the Ohio, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland river systems, and the crude overland trails like the Natchez Trace and the Louisville and Nashville turnpikes. Neither mode saw much traffic in the first decade of the nineteenth century.

After 1811, however, when the first steamboat appeared on the Ohio River, the scene changed quickly. Three years later Louisville welcomed its first steamboat, and by 1819 sixty-eight steamboats were plying western waters along with large numbers of barges and keelboats. Already Louisville was emerging as an export center to the South for such commodities as beef, pork, bacon, flour, whiskey, lard, rope and hemp, tobacco, steam engines, and other manufactured products. Most of this traffic moved south by water but some went overland, notably the stocks of hog and mule drovers, slave traders, and the goods of itinerant peddlers.

Expanding commerce meant growth and expansion. In 1820 the population reached 4,012; in 1840, 21,120; and by 1860 it totalled 68,033, twelfth largest in the United States. Manufacturing had come into the city as well. By 1850 the city had several iron and stove foundries and produced steam engines and other machinery. But Louisville remained primarily a distribution center despite the growth of manufacturing. A contemporary observer made this point clear in 1852:

Louisville contains twenty-five exclusively wholesale DRY GOODS houses, whose sales are made only to dealers and whose market reaches from Northern Louisiana to Northern Kentucky and embraces a large part of the States of Kentucky, Indiana, Tennessee, Alabama, Illinois, Mississippi and Arkansas. The amount of annual sales by these houses five million, eight hundred and fifty-three thousand (5,853,000) dollars. . . . There are thirty-nine wholesale grocery houses, whose aggregate sales reach ten million, six hundred and twenty-three thousand, four hundred (10,623,400) dollars.1

Such impressive growth did not come without problems. For its own needs as well as its livelihood Louisville depended heavily upon the fickle waterways. Some of the river’s problems it could solve. When expanding river traffic made the Ohio River falls an intolerable obstacle, a canal was built around them. Completed in 1833, the canal received some 1,585 steamboats, flatboats, and keelboats totaling 169,885 tons that same year. But no amount of enterprise could solve the major problems of low water, severe meandering, and physical obstacles.

The dry seasons left Louisville without any reliable connection with the outside world to obtain coal or other necessities. Improvements had been made in the overland routes and new projects abounded (at least on paper), but the turnpikes offered no permanent solution to the heavy flow of traffic.

To make matters worse, Louisville’s most bitter commercial rival, Cincinnati, had already cast an appraising glance at the potential of interior southern markets. Though founded 40 year later, the Queen City quickly outstripped Louisville. By 1840 Cincinnati boasted twice as many people and an impressive transportation system that included three canals, a river navigation project, several roads and turnpikes, and a few nascent railroads. Within a decade a contemporary observer could list fourteen macadamized roads, totaling 514 miles, and twenty railroads reaching the city. As yet all but two of these works traversed the region north of the Ohio River. Cincinnati’s primary commercial activity remained firmly rooted in the Ohio Valley, and that commitment was not likely to change. But more than one energetic businessman pondered the problem of how to reach the rich southern markets as well.

Confronted by this combination of internal frustration and external threat, ambitious Louisvillians grappled with their transportation problem. The successful advent of the railroad in the early 1830s offered a practical if expensive solution. A road from Louisville to Nashville would free the Kentucky city from the tyranny of low water—during which times Nashville actually became a serious competitor as distributing center for the border region. A railroad would not only avert commercial isolation, it would also neutralize Nashville and steal a march on Cincinnati in the quest for southern markets. This last point was no idle fancy, for a stupendous project to build a road from Charleston to Cincinnati had already been conceived.

The stakes of commercial rivalry were too high to dismiss such grandiose schemes out of hand. To survive Louisville needed to have a reliable connection to the interior. A road from Louisville to Nashville would be very expensive, risky, fraught with financial and engineering problems, and taxing upon the resources of all involved. It could conceivably lead to fantastic success, outright disaster, or the disillusioned abandonment that became the fate of so many opulent internal improvement projects. Regardless of the perils, several merchants, citizens, and editors understood clearly that the effort had to be made if Louisville wished to keep her future alive.

The agitation for a railroad from Louisville to the South began as early as 1832 and continued throughout the decade. One peripheral project, a road between Lexington and Louisville, made some headway, but other works received little support in Kentucky. The vast intersectional projects originating in Charleston and New Orleans absorbed considerable public attention even though neither road made significant progress. By the mid-1830s economic conditions had soured, and the panic of 1837 with its resulting seven-year depression dampened any lingering ardor for expensive projects. For over a decade the idea lay dormant.

The return of prosperity in the late 1840s changed the strategic situation abruptly. Tennessee in general and Nashville in particular renewed transportation schemes designed to capture southern markets for themselves. Two important lines, the first linking Nashville to Chattanooga and the second connecting Memphis and Chattanooga, were under construction. The strategically located Western & Atlantic Railroad between Chattanooga and Atlanta, completed in 1850, opened the rich interior of the Southeast and the Atlantic seaboard to Tennessee once the state finished its own roads. Nashville lavished aid on the railway projects in an attempt to end its dependence on the river and to advance its bid to become the great distributing center of the South if the Tennessee roads were built and Louisville remained inert. In addition Charleston and Savannah, through their railroad connections, were already seeking to strip Louisville of its domination of the tobacco market.

Other towns in Kentucky added to the pressure on Louisville. On December 17, 1849, a group of Glasgow citizens appointed a committee to ask the Tennessee legislature for a charter to construct a railroad from Nashville to the Kentucky state line. A week later a meeting in Bowling Green adopted resolutions urging the construction of a Louisville to Nashville railroad. If this were not enough, Nashville interests responded to such pleas by proposing a line far enough north to penetrate the Louisville market without actually entering the city. Such a road would effectively isolate Louisville between Cincinnati north of the Ohio and Nashville south of the river.

Louisville delayed no longer. A mass meeting of interested citizens early in 1850 adopted a resolution offering to subscribe $1,000,000 of city funds in a Louisville road and appointed a committee to investigate the proposal. One of the chief proponents of the road, Governor John L. Helm, who had advocated a north-south line for nearly fifteen years, used his influence to enlighten the state legislature. That body already had before it a bill seeking a charter for a railroad from Louisville to Bowling Green. To broaden its scope, the bill was amended to delete the town names and provide the company with complete freedom in locating the road. Eventually a bill passed the Kentucky senate approving several projects, including one connecting Louisville to the Mississippi River near the mouth of the Ohio.

On March 5,.1850, the legislature granted a second charter, this one to a company specifically interested in building a road between Louisville and Nashville. The charter authorized construction of a road from Louisville to the Tennessee state line, a capital stock of $3,000,000, and provisions for two branches. The first branch would leave the main line a few miles above the Rolling Fork River and extend to Lebanon; the second branch, located about five miles south of Bowling Green, would reach toward Clarksville and Memphis. The branch lines suggested the influence of downstate counties in protecting their interests, but the final charter owed more to the energetic Louisvillians than to anyone else.

The Tennessee legislature had already done its part. On February 9 it approved the charter for a road between Nashville and the present town of Guthrie, Kentucky, on the state line. But it guarded Nashville’s interests carefully by hedging the charter with restrictions: the road could approach Nashville only to the northern bank of the Cumberland River; it must pass through the town of Gallatin; and the railroad could convey freight across the river into Nashville only with horse-drawn wagons. Otherwise, the legislature reasoned, Nashville might become a mere way station instead of a terminus for traffic. Like their Louisville counterparts, Nashville merchants were all too aware of the stakes of commercial rivalry to overlook any detail. They envisioned a future in which Louisville would be an important satellite to the Tennessee capital, a relationship that might suddenly be reversed if Louisvillians gained control of the new company.

In short, the L & N Railroad was decidedly an offspring of the growing commercial rivalry between Louisville and Nashville. As the contrast between the company’s two charters reveals, both towns saw the road as their chief weapon in the battle not only against each other but against such potential outsiders as Cincinnati, Chattanooga, Atlanta, Memphis, and even New Orleans as well. Nor was the contest limited to the major competitors, for every hamlet and county in the vicinity between Louisville and Nashville viewed the project as a potential vehicle for its own prosperity. There ensued a mad scramble among these locales to persuade the new company to locate its line in their backyards. Increasingly the various factions interested in the road, especially the major towns, tended to view the yet unbuilt road as “their” company, whose chief duty was to advance the commercial ambitions of the community. Unhappily the company could not serve so many masters successfully, and it might one day develop goals of its own that differed and even conflicted with those of the various communities. But that day lay in the dim future, and meanwhile the road had yet to be built.

Construction of the L & N easily qualified as Kentucky’s biggest and most ambitious project of its time. Formidable engineering and construction problems awaited the contractors, and equally complex financial problems faced the new company. The proposed line would traverse an agricultural and mining region populated mostly by farmers, and it remained to be seen whether their local business could sustain so expensive an enterprise. Thus two immediate problems confronted the company: it had to choose the most practicable route, and it had to raise the necessary funds for so great a project. In a real sense the problems were related, for selection of the route depended not only upon engineering factors but also upon the competition among towns and counties to subscribe to the venture if they were included on the right of way.

That competition began at once. On June 17, 1851, the Louisville General Council approved a subscription of $1,000,000 to the new company. Subscription books were opened on September 4 and, after $100,000 had been subscribed, the company elected its first directors on September 27. The L & N’s first president, Levin L. Shreve, a prominent Louisville businessman, tried to deal simultaneously with the twin problems of money and location. Three surveying parties were put in the field, two working from Louisville and one from the north bank of the Cumberland. An early attempt to obtain federal aid for the road got nowhere. That left the directors with no choice but to solicit their funds from the welter of conflicting local sources.

L. L. Shreve, first president of the L & N, from September 27, 1851, to October 2, 1854.

A few subscriptions proved uncontroversial. Louisville later added $500,000 to its original subscription and private subscriptions ultimately totaled $928,700. Among the downstate counties, however, competition broke out between two alternative routes. The first, called the lower route, traversed Hardin, Grayson, Edmondson, Warren, and Simpson counties through such towns as Elizabethtown, Bowling Green, and Franklin. The upper or “air-line” route passed through Nelson, Larue, Hart, Barren, and Allen counties and included Bardstown, Glasgow, Scottsville, and New Haven as way stations. On September 29, 1851, the L & N board shrewdly passed a resolution stating that they had no preference for either route and that local subscription pledges should determine the decision.

Proponents of both routes took their cue and opened a hot bidding war. Among the lower route counties Hardin pledged $300,000, Grayson $300,000, Warren $300,000, and Simpson $100,000. The upper counties did not fare as well. Glasgow eventually offered $300,000, Hart County $100,000, and some of the other counties lesser amounts. But Nelson County, where Bardstown had so long advocated a north-south railroad, rejected a proposed $300,000 bond issue after a bitter fight. In Tennessee the fight went on no less energetically. Sumner and Davidson counties, through which either route might pass, each subscribed $300,000. A meeting at the Davidson County Courthouse on January 21, 1852, adopted a resolution favoring the upper route. As other meetings assembled elsewhere to adopt counter resolutions, local editors launched their own war of words.

Basically the dispute crystallized around the conflicting ambitions of Bowling Green on the lower route and Glasgow on the upper. The upper route was shorter but offered more serious engineering problems. The lower route passed through some large coal beds and could easily be linked to Memphis. This latter point grew increasingly important as citizens in the counties west of the lower route talked emphatically of the need for a road connecting Memphis to Louisville. Robertson County, Tennessee, went so far as to pledge $200,000 if the road went through its borders.

But the most dramatic step came from the town of Bowling Green. Painfully aware of the importance of the railroad to their future, certain of its citizens had obtained in 1850 a charter for the Bowling Green & Tennessee Railroad. Unwilling to tolerate the L & N’s vacillation over its route, these same citizens received a similar charter from the Tennessee legislature on February 13, 1852, and announced their intention of building a railroad from Bowling Green to Nashville. Such a parallel line would be an enormous waste of resources, but the company promptly put surveyors in the field and opened subscription books. When Bowling Green citizens approved a subscription of $1,000,000 to the company’s stock, the L & N board could no longer ignore the threat. On May 29, 1852, the board authorized Shreve to negotiate a consolidation of the two companies.

The independent action of Bowling Green may not have been the only factor in choosing the final route, but it certainly played a major part. The consolidation took place that same summer and the L & N gratefully absorbed the Bowling Green million dollar subscription. Soon afterward the other pieces fell into place. The company accepted Hardin County’s pledge and promised to put Elizabethtown on the line. Gallatin, Tennessee, received a similar assurance in return for the Sumner County subscription. The lower route had prevailed. A series of amendments to the charter, granted on March 20, 1851, legalized the public subscriptions and authorized the company to connect with the Mobile & Ohio, the proposed Memphis line, and the Ohio River just below the mouth of the Tennessee River. Even the suspicious Tennessee legislature relented somewhat and approved the amended charter in December.

Early in 1853 the situation looked promising for early completion of the road. The company had nearly $4,000,000 in subscriptions and its charter authorized the issue of $800,000 in bonds if necessary to complete construction. The surveying parties under chief engineer L. L. Robinson had declared the final route via Bowling Green “the only practicable route as regards cost, and ability to construct the Road, that can be found between Louisville and Nashville.”2 The survey estimated cost of construction at $5,000,000 and Robinson departed for England to let contracts. While there he negotiated the placing of $2,500,000 worth of bonds but could make no suitable construction deal. Turning closer to home, the L & N management on April 13, 1853, signed a contract with Morton, Seymour & Company to build the entire road. For the sum of $35,000 per mile that well known construction firm promised to complete the 185-mile road in thirty months.

Despite this auspicious start the project ground to a temporary halt almost immediately. The first iron contract, signed in June, 1853, called for 3,000 tons to be delivered during the first three months of 1854. Grading, masonry, bridge and railway superstructure work began in May, 1853, only to be suspended for lack of funds. The bonds Robinson placed had not been delivered immediately, and the Crimean War, coupled with crop failures in Europe, depressed the bond market enough to cause the L & N negotiation to collapse. Of the batch only $750,000 were eventually placed, and these in Paris. Subscription money from the various towns and counties was to be paid in installments over a period of time. Most of the pledges came in promptly but in too small amounts to meet immediate needs.

Steeped in gloom, Shreve had no choice but to order total suspension of work in June. Robinson, who had written a thorough analysis of the road’s potential revenue sources, returned from London and resigned as chief engineer. Dissatisfaction over the project arose in Louisville, where the board of aldermen expressed a lack of confidence in Shreve and his board. Part of the squabble involved certain Louisvillians who objected strenuously to the location of the L & N’s depot at 9th and Broadway. Determined to have their way, they threatened to scuttle the whole project if all else failed. The aldermen also resented the board’s inability to present an exact report of expenditures. During a convention on June 24 Shreve, absent in Europe, resigned by letter. Eventually the aldermen backed down, but Shreve insisted that his resignation stand. On October 2, 1854, he was replaced by none other than Governor Helm.

John L. Helm, president of the L & N from October 2, 1854, to October 2, 1860.

Efforts to revive work on the line went slowly and met endless frustration. Marion County had subscribed $200,000 for a branch to Lebanon, but unprecedented low waters during the late summer prevented the delivery of any iron. That delay further aggravated existing financial problems. The original contractor, Morton, Seymour & Company, grew disgusted and withdrew from their contract. The new contractor, Justin, Edsall & Hawley, began work in September, 1854, but could proceed no faster than funds trickled in. Both the city of Louisville and the Tennessee legislature took steps to furnish immediate financial aid.

The Louisville assistance was designed primarily to complete the Lebanon branch, and to that end the company sought to complete the first thirty-mile portion of road to New Haven. In July of 1855 the first rails went down and two months later the entire section of roadbed was ready for iron. During August a special train toured the completed eight-mile stretch of track. Still the work went slowly amidst an array of hardships. An epidemic of cholera depleted the labor force, a crop failure inflicted great suffering, another drought brought river traffic to a halt, and delayed the delivery of materials. Abroad Europe remained at war and at home sectional strife moved ever closer to the boiling point. At the local level the L & N found itself at war with some of its subscribers—notably the Tennesseans, who resented the fact that all construction work was taking place on the Louisville end. Many optimists had predicted completion of the road by 1855; that year had come and nearly gone, and some observers wondered whether the road would ever be finished.

According to Robinson’s thorough report of 1854 the construction crews would encounter no serious obstacles beyond a few minor rivers until the line reached Muldraugh’s Hill, a few miles north of Elizabethtown. The hill, a solid 500-foot limestone structure perpendicular to the route, presented the most imposing engineering problem on the road, and there was no good way around it. The tunnel proposed for it was to be 1,986 feet long and would pass 135 feet below the summit. Robinson estimated the cost of grading the five-mile stretch at $520,000.

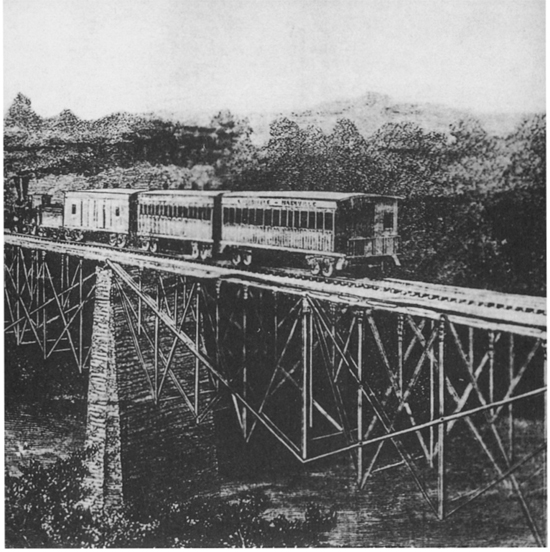

Beyond Muldraugh lay the Green River, rimmed by hills on the north and smaller knobs to the south. Any approach to the river would be high and difficult, and the cost of a bridge was figured at $140,000. But the finished product proved to be the largest iron bridge in the United States with a total length, including approaches, of 1,800 feet. Final cost ran closer to $165,000. Once past the Green, the crews would confront a landscape of undulating cavernous limestone formations until they crossed the Barren River. No other obstacles would delay work until the line reached Simpson County, where the countryside gradually rose to the summit of the Tennessee Ridge, which divided the Barren and Cumberland rivers. The Ridge lay perpendicular to any possible route, being unbroken between Clarksville and the Cumberland Mountains. Like Muldraugh’s Hill it had a gradual fall on one side and a sharp precipice on the other, with short, rapid drainage to the river. The rest of the route to Nashville offered little respite, running through heavy rolling limestone formations.

As the financial picture slowly brightened in 1856, the company pushed its crews forward and succeeded in restoring a semblance of public confidence. For one thing, the courts upheld the legality of the county bond issues to aid a private corporation. For another, Louisville approved a second $1,000,000 subscription to the company. By midyear the company had expended $1,212,137 on construction and opened twenty-six miles of road. With another $2,000,000 at hand the board put the whole road from Louisville to Nashville under contract and ordered 7,500 tons of iron for the main line. By October the line reached Lebanon Junction and work commenced on the branch to Lebanon. Completion of that link would be especially important, for it would provide a source of income to the struggling company from a potential market of about fifteen southern and eastern counties.

In driving the work forward Helm lost no opportunity to emphasize the importance of the road to local interests. Much of the grading and other work had been let to farmers along the route who took their pay in company bonds. Helm applauded this exchange as a significant step in making the road a home interest. In the Annual Report for 1857 he noted proudly,

That the people along the line should become the holders of these bonds is eminently proper. By such sale and purchase you secure for your road many active and influential friends, and secure for it the management of real friends. Such purchases are usually made by men whose business or property will be advanced by the road. ... It will be a proud achievement if Tennessee and Kentucky will, as they can, build this great connecting link in the chain of roads south and north, without subjecting it to liens and mortgages held by capitalists who have no other motive than that of profit and ultimate ownership.

Helm had more than regional patriotism for which to thank the local farmers and workmen, for the spiraling cost of labor and supplies put a severe strain on the company’s outside contractors. Moreover, work was delayed by low water and by the inability of Louisville bonds to attract buyers. Indeed the latter could not even be exchanged for goods and services, and at one point Helm personally redeemed $20,000 in Hardin County bonds. As usual expenses exceeded original estimates, and hurried requests for emergency funds led inevitably to charges of mismanagement. Disgruntled by the meager amount of iron laid at their end of the road, Nashville interests renewed their cries of conspiracy. Nevertheless, by autumn of 1857 the tide had turned. To ease the financial crisis several Louisville interests stepped in and purchased $300,000 worth of the L & N bonds. Their action kept the company in funds until the bond market loosened. At the same time two key men took positions with the L & N and did much to guide the last steps of construction. James Guthrie, former Secretary of the Treasury under Franklin Pierce, assumed the vice presidency. Born in Nelson County in 1792, Guthrie attended school in Bardstown before going into business at the age of twenty. For a time he hauled produce to New Orleans on flatboats. When that enterprise did not slake his ambitions, he returned to Bardstown, studied law, and opened a practice in Louisville in 1820. He accepted a position as prosecuting attorney for the county and pursued his duties so vigorously that on one occasion an incensed rival lawyer shot him. The wound left Guthrie lame for life but only reinforced his enormous energy, coarse demeanor, and powerful will.

James Guthrie, who as president completed the L & N and guided it during the difficult years of the Civil War, from October 2, 1860, to June 11, 1868.

During the 1820s Guthrie plunged into politics with gusto. He became an ardent Jacksonian Democrat, served nine years in the state legislature before declining renomination, and was president of Kentucky’s constitutional convention in 1851. Though business commitments increasingly absorbed his attention, he gravitated into national politics. While Secretary of the Treasury he gained some reputation as a reformer. He won election to the United States Senate in 1865 but retired after three years because of ill health. In business Guthrie played a vital role in raising funds for several Kentucky rail projects. He also helped secure charters for the Bank of Louisville and the University of Louisville. His political shrewdness and indomitable personality did much to remove the last financial obstacles confronting the L & N.

Albert Fink entered the company’s service as a construction engineer but soon rose to general superintendent. Born in 1827 in Lauterbach, Germany, he migrated to the United States in 1849 after completing college in Germany. Trained as an engineer, he won an impressive reputation as a bridge designer. He was the first engineer in America to attempt a 200-foot span, and his effort, the Baltimore & Ohio Bridge over the Monongahela River at Fairmont, Virginia, earned him lavish praise.

Fink remained in the service of the B & O until the road’s completion in 1857. His move to the L & N gave him the opportunity to display a variety of talents. His genius for engineering continued to be widely acclaimed. It was he who designed the Green River Bridge which, like the Fairmont span, utilized his own invention, the Fink Bridge Truss. With the L & N, however, he revealed great executive and administrative ability as well, though he remained deeply involved in the study of railroad problems. Standing six foot seven and dubbed the “Teutonic Giant,” Fink was destined to leave a deep imprint on the L & N’s history.

Under fresh leadership and with the financial crisis solved, work went forward rapidly. By November the company was operating seventy- four miles of road out of Louisville and twenty-seven miles north of Nashville. The Muldraugh’s Hill tunnel neared completion and only the several long bridges remained to be built. Lebanon welcomed its first train early in 1858, and on March 8 trains began running a regular schedule on the branch. An impressive new depot in Louisville, designed by Fink and far advanced of similar structures elsewhere, was dedicated in 1858. When Mayor John Barbee declared a half-holiday on the occasion a huge crowd turned out to hear the speeches and to watch President Helm roll the first barrel of freight into a freight car. After the small wood-burning locomotive chugged slowly away, the cheering crowd milled curiously around the 23-acre depot grounds.

Helm hoped to complete the road before Christmas of 1859. To insure ready cash for all remaining work Guthrie executed a $2,000,000 mortgage upon the main line. The company closed a contract with the federal government for handling the mails, and arranged to purchase the Kentucky Locomotive Works at Louisville. Shops were also being constructed in Louisville, a turntable forty-five feet in diameter had been installed, and a tank house went up along with two 12,000-gallon tanks. As of October 1, 1858, the company operated ten locomotives, seven passenger cars, three baggage cars, thirty-two box cars, and 102 miscellaneous cars. It had long ceased to be a paper enterprise.

Steadily the gap between the Louisville and Nashville crews narrowed. On August 10, 1859, the road opened from Nashville to Bowling Green, less than twenty miles from the approaching Louisville line. A great barbecue for 10,000 people at Nashville celebrated the road’s entry into Bowling Green, and already through trips to Louisville were being run by a combination of rail and stagecoach in only sixteen hours—some eleven hours faster than the old stagecoach time. The Green River Bridge had been completed, though the tunnel at Muldraugh’s Hill would not be finished until April, 1860. To avoid delay the crews put down temporary track for the ascent.

Part of the first L & N passenger station at 9th and Broadway in Louisville, opened in 1858.

It seemed clear that Helm would have his line completed before Christmas. On September 6 a delegation assembled in Nashville to celebrate the impending triumph. The Kentucky crews laid their last rail on October 8 and their Tennessee counterparts finished ten days later. On October 27 a special train with 200 passengers, including the L & N board of directors, the mayor of Louisville, various councilmen, newspapermen, and other notables, left the Kentucky city for the first run to Nashville. Crowds lined the track for much of the distance and numerous stops were made. About twenty miles from Nashville the special was met by a sister train bearing an equally heavy burden of dignitaries, including Helm and Vernon K. Stevenson, president of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad and a leading Tennessee railroad entrepreneur.

After an overnight stop at Edgefield the excursionists proceeded across the Cumberland River Bridge to a formal reception by Nashville’s mayor and city council. Later the governor entertained the entire party at the state capitol. This last leg of the journey, across the Cumberland River, had been made possible by a change of heart in the Tennessee legislature. Eventually that body had allowed the L & N to cross the river and establish a depot in Nashville, and in 1855 loaned the L & N and the Edgefield & Kentucky Railroad $100,000 jointly to construct the bridge. To demonstrate the bridge’s strength to the visiting parties, three locomotives were put on the span at one time. After a sumptuous round of wining and dining the train returned to Louisville on October 29. Two days later trains began running a regular schedule between the terminal cities: two passenger trains each way every day except Sunday, when only one was run, and one daily through freight train.

More than nine years after receiving its charter, the L & N had completed its line. The final cost amounted to $6,674,249 on the main stem and $1,007,736 on the Lebanon branch. The debt of the main line totaled $4,705,500 with annual interest of $279,830, and the company sorely lacked adequate rolling stock for its new role as a through line. Even the moment of jubilation was marred by the resurgence of demands that Helm resign the presidency.

For some time Helm had been under fire from certain stockholders who accused him of incompetence and exorbitant expenditures on constructing the road. Stubbornly Helm refused to resign until his line was finished, but once the through connection was made he could no longer fend off his detractors. On February 4, 1860, two L & N directors published an open letter demanding Helm’s resignation on the grounds that they had voted for his reelection only on condition that he step down once the road was completed. After a sharp exchange of words Helm got no support from his board and resigned on February 21, to be replaced by Guthrie. One other factor had contributed to his downfall, and had in fact been a storm center of controversy for a decade: the Memphis branch.

The Memphis branch originated in the clashing hopes and fears among merchants in Memphis, Louisville, and the towns between the two cities. In each city a substantial number of citizens argued that such a road would enrich the trade of both towns and, more important, free them from the tyranny of the river. This last point proved decisive, for by the late 1840s the Mississippi and Ohio rivers above Memphis had become dangerously unreliable. Perilously low during droughts and clogged with snags and treacherous sandbars, the waters took a frightful toll of the larger, heavier steamers of the era. And the situation grew worse every year. By the 1850s it was considered foolhardy to risk a valuable cargo on the river, where losses reached nearly a ship a day and the shells of grounded steamers littered the shoreline. One contemporary Cincinnatian estimated that losses of river craft during 1855–56 were high enough to build a railroad from Louisville to Memphis with enough left over to operate the road.

The opposition to a Louisville railroad, no less devoted to local interests than their Kentucky counterparts, feared that the project would result in a drain of Memphis trade to Nashville. These same interests had also opposed a proposed road from Memphis to Nashville but in vain. After three years of diverse agitation the Nashville & Tennessee Railroad Company obtained a charter from the legislature in 1852. The charter authorized construction of a road from Memphis to Paris, Tennessee, a distance of 130 miles. Beyond Paris the future was uncertain. The road might go on to Nashville, head directly for Louisville, or seek a connection with the yet incomplete L & N. Another road, the Memphis & Charleston, had already begun construction toward Chattanooga.

At about the same time certain Louisville interests, part of the L & N’s management, and the two counties southwest of Bowling Green (Logan and Simpson) developed their own interest in a Memphis branch connecting to the L & N at Bowling Green. To some this interest reflected a vision of bringing Memphis and its surrounding territory under Louisville’s commercial influence; to others the branch meant only a device to broaden support of the L & N project itself. Robinson made a preliminary survey between Louisville and Memphis and found the route very favorable. His line scarcely varied half a mile from an airline and had very modest grades. In his 1854 report Robinson recommended such a branch and Helm later supported it ardently, but for the time being nothing was done.

While the Louisvillians dawdled, the Tennessee towns seized the initiative. At once the familiar chess game commenced over both the proposed route to Paris and the destination beyond. Each of the three alternatives beyond Paris received support, with many merchants in both Memphis and Louisville leaning toward a connection with the L & N. The severe coal shortage in Louisville during November, 1853, caused by low water, spurred that city’s efforts to eliminate dependence upon the river as quickly as possible. Nearly half the population of Louisville depended for their livelihood upon industry, which in turn depended upon a regular supply of coal. The Memphis line promised to secure coal from western Kentucky mines much more cheaply than the cost of Pittsburgh coal.

At last the Louisville interests acted. On December 5, 1853, the Tennessee legislature authorized a charter for the “Memphis to Louisville Airline Railroad Company.” Eleven days later the Nashville & Memphis Company obtained amendments to its charter that facilitated connection to the Airline. Both companies received the right to connect with a third company, the Memphis, Clarksville & Louisville. This road, no less a product of commercial fears and ambitions, originated with the Bowling Green & Tennessee—the project used so effectively by Bowling Green interests to lure the L & N main line to their city. When the pretense of building to Nashville was dropped, the Tennessee legislature in January, 1852, chartered a new road from Memphis to Louisville via Clarksville. The new company, composed of both Kentucky and Tennessee interests, received the right to start construction at any time and connect with any other company, including the L & N at Bowling Green.

Coming as it did on top of the projects mentioned earlier, the Clarksville seemed like one more piece in a bewildering jigsaw puzzle. If the relationships of companies seeking a line between Louisville and Memphis seem hopelessly entangled, it is only because they were. The reasons for the confusion, overlapping, and outright duplication can only be touched on here. They include the fiercely conflicting commercial aspirations of all the towns and counties involved (especially Memphis), indecision among the Louisville interests, sharp disagreement over whether the road should go to Louisville or Nashville, the L & N’s absorption in its own problems, the hostility of some Nashville interests, and the eagerness of the State of Tennessee to get some system of roads linking Memphis to the rest of the state.

The importance of the Clarksville project lay in its strategic location almost directly between Paris and Bowling Green, the most feasible connection to the L & N. That fact alone rendered the connection alternative more attractive to most of the parties involved even though both Tennessee companies publicly professed their intention of building on to Louisville. On March 7, 1854, however, the Clarksville obtained from the Kentucky legislature the authority to make any advantageous connection it wished. Having formally organized the company in May, 1853, the Clarksville was well into a survey of its proposed line and had already appealed to the L & N for financial aid.

Accepting the drift of events, the Nashville & Memphis formally obtained a charter amendment allowing it to make connections to the north. Soon afterward the company changed its name to the Memphis & Ohio Railroad and plotted a final route toward Paris. An acrimonious dispute over location of the depot in Memphis helped delay work until August, 1854; by October of 1855 some twenty-five miles of track had been laid and thirty more were ready for iron. Ironically, the Memphis & Ohio faced a rather unique problem for its day: the indifference and outright hostility of citizens living along the route. Standing aloof from the commercial aspirations of the terminal cities, they saw no advantage for themselves in the coming of the Iron Horse. The factional squabble over location of the route flared up anew as the pro-Nashville interests reasserted their demands.

In 1856 the picture brightened considerably. After another long debate the Memphis & Ohio board decided to locate the road directly to Paris via Brownsville, and in April construction started again at several points on the line. The company also petitioned the legislature for the right to consolidate its charter with the Clarksville, but the latter showed no eagerness to merge. More important, Helm and the L & N now took a close interest in the work. Believing that an amalgamation of the two Tennessee roads would insure completion of both roads, the L & N surveyed the territory between Bowling Green and Guthrie, Kentucky, on the state line. By June of 1857 the Clarksville had fifty-six miles of road in operation and another fifty-nine miles under contract. The Memphis & Ohio was making steady if less spectacular progress.

If the two lines did consolidate and complete construction, only the gap between Guthrie and Bowling Green would remain to be closed. Helm decided the L & N could no longer shirk an active role. In his Annual Report for 1857 he argued that “This connection is too important to be longer delayed. When once begun it will be finished. It is, therefore, a duty which the friends of the several routes owe to themselves ... to present their subscriptions, have the route selected, and go at once to work.” Helm practiced exactly what he preached; the L & N board took steps toward financing the connection project. Not surprisingly, his action touched off another loud controversy.

Prior to 1858 part of the Louisville press had treated the whole Memphis problem with cavalier disdain. The steady progress of both companies, however, drove alarmists in Louisville and elsewhere to funnel their wrath onto the L & N management for aiding and abetting the enemy by committing itself to the branch. Most of those opposing the Memphis were merchants and related interests who saw the linking of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers as detracting from Louisville’s trade rather than enhancing it. Led by the Louisville Courier these interests insisted that the L & N should concentrate upon finishing its own line and forget about branches. Moreover, they demanded, where would the money for the branch come from? How could a company so strapped as the L & N justify such an expenditure? In portentous tones the Courier exclaimed, “We do not wish or intend to attack the past or present management of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, unless we are driven to it, though much, very much, might be truthfully said upon this subject which would startle the community.”2

Helm countered these charges in his Annual Report for 1858. He emphasized that the Memphis road was fast becoming a reality with or without L & N help, and to ignore that fact invited disaster. By building the branch Louisville could secure for itself at small cost valuable connections along both the major trade routes below the city: southeast to Nashville and the Atlantic coast and southwest to Memphis and the Gulf. More important, Helm argued that, with the Memphis branch complete, Louisville would become “the single link connecting the southern with the northern and eastern roads.”3 Such an opportunity, if ignored now, might never come again.

Part of the money for the project came from a Louisville city council ordinance providing $300,000, and part came from the counties through which the branch passed. Logan County led the subscription list with $300,000 and Helm later justified his defense of the branch in part as protecting that county’s interests. Contracts were let for grading and bridge masonry in December, 1858, and work toward Guthrie progressed steadily during the next year. During 1858, too, the Tennessee legislature ordered the Clarksville and Memphis & Ohio companies to consolidate and promised additional financial support after the merger. But a 24-mile section north of the Tennessee River remained unfinished, and the Clarksville balked at any consolidation until this gap had been closed.

On February 1, 1859, the Memphis & Ohio completed its line to the juncture with the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. Since the latter road ran to Columbus, Kentucky, on the river, the Memphis merchants need no longer fear low water. But considerable work remained for the road to reach the Tennessee River; by 1860 over thirty miles of road lay unfinished. The Clarksville had almost completed its road in 1859 except for the gap between Paris and Clarksville. Amidst the final push, however, the bridging problem arose to plague the company. Too late it was discovered that the bridge over the Cumberland River had been built too low. The passageway allotted for river craft proved too narrow and the current too swift for the pilots to hit it consistently. Steamer after steamer lost their stacks to the bridge and one of the larger vessels, the Minnetonka, was nearly demolished when she hit the bridge at high water. The ensuing stream of litigation left the company with no choice but to lift the existing bridge or rebuild it entirely.

Not even steady progress on the Memphis branch could save Helm’s deteriorating position. His resignation in February, 1860, came after the opening of the main line but before completion of the Memphis branch he had supported so vigorously. The L & N’s branch between Bowling Green and Guthrie opened on September 24, 1860, and trains began running to Clarksville that same day. On the 18th a special train carried the Louisville directors over the entire new road to Clarksville where, ironically enough, the Clarksville president, General William A. Quarles, shook hands not with the deposed Helm but with James Guthrie. The total cost of the L & N’s portion of the road amounted to $848,733, somewhat less than originally predicted.

Tracklaying on the gap between Paris and Clarksville did not commence until October 24, 1860. The last rail on the Memphis branch went down on March 21, 1861, but even then the bridge over the Tennessee River remained unfinished. Not until early April did trains run to Memphis on a regular basis. But by that time Confederate troops had already fired upon Fort Sumter.

Though completed during the closing years of the sectional crisis, the L & N obviously did not contemplate a future shaped by civil war. The company did envision a role in southern commerce for which it was admittedly unprepared and underequipped. That vision, though delayed and somewhat deranged by the war, did not change substantially in the years immediately after Appomattox. The goal of becoming the primary commercial artery to the Southeast and Southwest scarcely had time to assume shape in the sixteen months between the opening of the main line and the outbreak of hostilities. Even so, several major problems appeared in that brief period.

First of all, the road could hardly be called finished even after it had opened for business. After completing the Memphis branch, the L & N had 268 miles of road in operation. Most of the line had not yet been fully ballasted, and large portions had no ballast at all. Virtually all the company’s money had gone into construction work, and local banks hesitated to lend money for the ballasting. Several important stops lacked depots, and only hastily built platforms kept waiting freight off the ground.

The most perplexing problem, however, concerned rolling stock. By the spring of 1861 the company owned thirty locomotives, twenty-eight passenger and baggage cars, and 297 freight cars. Prior to the summer of 1860 this appeared to be more than enough equipment to do the business at hand, and there was no money for additional stock anyway. But it quickly became clear that the peculiar traffic of the L & N and its branches would not make very efficient use of existing equipment. For one thing, agricultural products naturally tended to create a heavily seasonal traffic that ran the road ragged at harvest time and left cars empty the rest of the year. Through freight and non-agricultural products pursued a more regular schedule, but it became painfully evident as early as 1860 that this traffic ran overwhelmingly in one direction. During the ten months ending June 30, 1861, 83 per cent of the L & N’s freight revenue derived from freight transported southward, while only 17 per cent came from northbound traffic. That meant a veritable crunch to handle business at Louisville and a lot of empty cars rolling back from Nashville.

To be sure, the traffic for 1860 involved certain abnormalities, but even the abnormalities pointed up the L & N’s traffic dilemma. Part of the freight involved the hoarding of provisions and supplies by southern states alarmed by the threat of war. Another part, however, arose from a bizarre sequence of events that created a crisis during the summer of 1860. A severe drought that season resulted in short crops and a heavy demand for foodstuffs from the northern grain states. Transshipped via Cincinnati, the crush of provisions descended upon transportation facilities at the worst possible time. The river was too low to be reliable, which threw virtually the entire burden upon the woefully understaffed L & N. At a time when the road’s capacity was barely 500 tons of freight a day, 400 through and 100 local, the demand for southbound through traffic suddenly jumped from about 200 to over 1,000 tons per day.

This avalanche of traffic could not have caught the L & N more disorganized. Naturally the rolling stock proved wholly inadequate to the demand. When the company rushed most of its help northward to deal with the mess in Louisville, it could not secure labor in Nashville to help unload freight cars. Nor did the Nashville city council help matters by passing ordinances that prohibited railroad employees from working on Sundays. As a crowning blow, both Guthrie and his superintendent fell ill and were hors d’combat during most of the crisis. In their absence the company’s billing system got thoroughly fouled up, agents were forced to refuse goods because they lacked bills of lading, and the storage of waiting consignments became a serious problem.

Into this sea of woes the press of Louisville, Nashville, Cincinnati, and numerous other towns waded with caustic glee. Denouncing the whole affair as the “Louisville and Nashville blockade,” they censured the L & N management for its pitifully inadequate rolling stock. Such a charge against a newly opened railroad subjected to an apparently freakish situation was obviously absurd, but more basic issues lay behind the vitriolic editorials. Specifically there lurked the ancient clash between Louisville and Cincinnati merchants. Viewing the L & N as their own special weapon in the commercial cold war, Louisville merchants complained bitterly that the road was actually discriminating against them in favor of Cincinnati interests. The company, they charged, would accept only local freight from them but would accept through freight from Cincinnati merchants.

In one sense the charge was true, but it was also largely irrelevant. Under the circumstances both cities wanted to monopolize the road. Unhappily for Louisville, many southern farmers were making large purchases in Cincinnati, subject to immediate delivery. The railroad could hardly be held responsible for that situation, and it faced the difficult task of making good on the deliveries between the millstones of outraged Louisville merchants and impatient customers southward. Things were no better at Nashville, where merchants fretted loudly over the uncertainty of freight shipments (and unloading). Some of the city’s merchants charged the L & N freight agent there with discriminating against their interests. They demanded the right to choose their own agent but the company refused, and the furor continued until the blockade eased.

Despite its relative innocence of the charges leveled against it, the L & N suffered grievously from the blockade episode. The most permanent damage probably lay in the area of public relations, for the incident marked the beginning of a relationship between the corporation and the public that would deteriorate steadily over the next fifty years. Part of the trouble could be dismissed as simple misunderstanding, but much of it involved such substantial issues as the growing power of the corporation within the state and the increasing divergence of goals between the corporation and the various interest groups of its terminal cities.

On the positive side, the blockade should have provided a valuable educational experience for the L & N management. Besides demonstrating the dangers of an aroused public, it underscored in bold relief the chronic dilemma of calculating rolling stock for a heavily seasonal and one- directional traffic. The fact that nearly all southern railroads confronted this problem offered little consolation to the L & N in its search for means to furnish maximum service with minimum equipment. The attempt to find cargoes for empty northbound cars would play an especially important role in the L & N’s future. The blockade also clearly revealed the railroad’s delicate political role as a pawn in the fierce commercial rivalries of its tributary towns. Finally, the incident reinforced the familiar adage that the railroad business consisted largely of expecting the unexpected and dealing with it successfully.

In short, the L & N, during the brief period 1859–61, groped for some kind of norm on which it could estimate prospects for the future. But there was not enough time to calculate a norm, and if anything the prewar experience suggested that no such reliable guide existed. As a result the L & N found itself swept into the maelstrom of war before it had defined its goals, pinpointed its basic strategy, or even achieved a sense of identity. Problems remained unsolved and questions unanswered, but the heat of battle swept them out of sight until another, calmer day.