Albert Fink, engineer and strategist who did more to shape the early destiny of the L & N than any other individual.

The defeat of the Confederacy thrust a host of decisions upon the shoulders of southern railroad managers. Wartime demands had so twisted the business and functioning of every line as to destroy any workable definition of normal peacetime operations. Part of the distortion involved simply the abnormal press of military traffic which would gradually disappear as regular trade relations resumed. Another part involved a more permanent alteration in the economic environment itself and would require major policy adjustments by every company. Indeed the South’s economic environment in 1865 scarcely resembled that of 1860, though many of its characteristics were but the accelerated development of trends already evident in the 1850s.

The most obvious difference was the South’s ravaged economy. Exhausted and trampled by four years of conflict, the section needed massive doses of capital, strong leadership, and much patience to reconstruct the agricultural prosperity of the 1850s. Plantations were overrun and in disrepair, the labor supply was uncertain, banking and credit facilities were nonexistent, and state governments lacked cohesion or direction. Commercial relations disrupted by the war had to be restored, and the industrial potential of the region, so vital to economic diversification, remained pitifully unrealized. Over every activity hung the uncertain political atmosphere of Reconstruction. The crippled transportation system shared all these defects and added a disheartening dilemma of its own: restoration of the transportation system was needed to rehabilitate the South’s economy, but by the same token the financial survival of the railroads depended upon a revived economy capable of supporting them.

For nearly all southern roads, the task of restoration superseded all other problems and absorbed most of the officers’ attention until 1868. As already noted, the L & N faced no such difficulties and so possessed an enormous advantage over other southern roads. But it had no immunity from some basic adjustments required by the altered economic environment. Unlike the more established southern companies, the L & N lacked any real prewar model upon which to calculate its future strategy. Whether or not the absence of a traditional set of policies hurt the company in a changing environment, it did force L & N officers to make some momentous decisions within a year after Appomattox.

Though the debate over policy began as early as 1863, the balm of wartime profits tended to dampen serious differences of opinion. But the disappearance of that abnormal prosperity soon underscored the urgency of fashioning a new strategy for peacetime. Inevitably the debate produced a sharp clash of positions between those advocating a bold, aggressive policy and those favoring a prudent consolidation of the company’s existing strategic advantages. Since the two positions were based upon opposing interpretations of the postwar economic environment, it is helpful to consider that environment briefly.

With few exceptions, the control of southern railroads remained in the hands of the same men who dominated them before the war. Like the leadership of the L & N, they had built the early railroads and represented powerful commercial and financial interests in the territory drained by the road, especially the key terminal city. Since their economic horizon rarely extended beyond that city, they assumed a naturally provincial attitude toward the road’s function. They conceived it primarily as their most potent weapon in the growing rivalry between the various commercial and distributing centers of the South.

Possessing strong community and regional ties, antebellum southern railroad leaders sought to achieve three basic goals. First, they hoped to make the road a profitable long-term investment in itself. Secondly, they wished to localize traffic, and thereby commercial activity, at the principal terminus. Finally, they saw their road as the essential tool for developing the economic resources of the region tributary to the road. In one sense, the latter two points melded together, for extension of the road both opened adjacent areas to the marketplace and prevented rival lines from tapping the area’s resources for some other terminal city. Since nearly all southern railroad leaders had external investments, their transportation work became a logical extension of their other financial interests.

From this localized perspective emerged two closely related concepts, labeled for our purposes territorial and developmental, that guided southern railroad policy-making prior to the Civil War. The first formulated a definition of the road’s marketplace and tributary region; the second delineated the basic principles upon which the company should be managed. Together the twin concepts comprised the essence of what became popularly known as local control. It assumed that the road existed mainly to service its key terminus and tributary region. The welfare of city, territory, and company alike required that all concerned recognize their mutally dependent relationship and the need to perpetuate it. That meant, among other things, keeping the company out of the hands of “outsiders,” whose economic interests were not directly related to the road’s territory. “Foreign” investors and bondholders could be tolerated, even cultivated, so long as they acquiesced in a policy of localizing traffic at the chief terminus. But outside parties with interests in competing lines or cities were anathema.

The territorial concept presupposed the basic tenet of one road for one territory. The region drained by the road constituted its realm of control, much like a feudal barony, with boundaries determined by the line’s terminals and connecting points. Julius Grodinsky’s succinct description of western territorial strategy aptly fits southern conditions as well:

To serve a territory with no railroad competition was the ambition of every railroad operator. . . . An exclusively controlled local territory was a valuable asset, as long as it lasted. A monopoly of this kind was perhaps the most important strategic advantage of a railroad, provided, of course, the monopolized area either originated valuable traffic or served as a market for goods produced in other areas. Territory thus controlled was looked upon as “natural” territory. It belonged to the road that first reached the area. The construction of a line by a competitor was an “invasion.” Such a construction, even by a business friend of the “possessing” road, was considered an unfriendly act. The former business friend became an enemy.1

In like fashion southern railroad men conceived of their road as having exclusive possession of the commerce in its territory. Referring to this right as “the natural channels of trade,” they resented any encroachment upon it and fought bitterly to seal it off from any invasion. To protect the interests of their companies, they did not hesitate to enter directly or indirectly into state and local politics. Virtually every road counted influential political figures among its officers and board members. In the confused political turmoil of Reconstruction, these officers usually stood out as prominent representatives of local interests.

The developmental concept involved several considerations. In broad terms it required that profits and development be conceived as long-term goals, that the company be run primarily to satisfy investors rather than speculators, and consequently that the stock be tightly held and protected from rapid turnover and fluctuation in value. This last goal could be more easily achieved in those cases where the state, the terminal cities, or counties along the route held sizable portions of the outstanding equity. Long-term success depended heavily upon the cultivation of economic resources along the line, whether agricultural, mineral, or manufacturing. For that reason the managers of most roads worked actively to stimulate immigration into the regions along their right-of-way. They built branches and spur lines to provide access to market for infant industries and mining endeavors. Some even devised special traffic arrangements to foster the development of certain products.

Traditional developmental policy embodied specific attitudes toward dividends and maintenance as well. Obviously regular dividend payments were essential to any policy stressing long-term investment, and most southern officers favored such a schedule. But the need for capital to refurbish and equip the lines often clashed with dividend goals and forced difficult choices upon the decision makers. In most cases the officers tended to subordinate dividends to the necessity of plowing back earnings into maintenance and improvements. Since the pressure from stockholders for income remained persistently intense, most managers walked a delicate line in proportioning their income. Thus, the stronger southern lines paid regular dividends in prosperous times but promptly cut back when business dropped off. In such situations the dividend rate frequently became a tactical device for gaining stockholder approval on other issues deemed vital by management.

Finally, the territorial and developmental concepts converged to define the antebellum attitude toward expansion. The territorial concept assumed the primacy of local traffic, with its higher rates, as a source of income for the company, with each road serving a secondary function as links in a larger system for through traffic. The developmental concept emphasized a logical pattern of growth for the company, primarily in the form of constructing small branch lines as feeders to the parent road. The effect of this combination was to define expansion as an essentially intraterritorial activity for both offensive and defensive purposes. On this basis new mileage would be added in an orderly fashion and usually on a small scale. It would exploit hitherto untapped resources and protect them from ambitious encroachers. And it would not involve an excessive drain upon that scarcest of commodities, capital.

Because the territorial-developmental concept had worked so well before the war, and because men do not easily discard proven formulas for success, southern railroad leaders invariably resorted to it as their standard for devising postwar policies. Unfortunately, many of the assumptions behind the traditional conceptual framework no longer held true. For most roads, the cost of rehabilitation disrupted antebellum policies by burdening the roads with additional debt and thereby enlarging fixed costs. To service this extra financial load the companies would require more traffic at higher rates, but both proved difficult to obtain in the impoverished postwar South. In fact, the trend of southern freight rates had been downward even before the war. The old reliance upon patient development of local traffic would continue, but obviously it could not provide immediate relief from pressing financial needs.

For most managers, therefore, the only feasible alternative lay in securing more through traffic to augment local income. But there, too, the environment was changing drastically. The traditional primacy of local traffic, and indeed of the whole territorial concept itself, derived in large part from the fact that competition within the skeletal southern network scarcely existed for through traffic and was virtually absent at the local level. Except for the omnipresent steamboats, most of the early southern roads had their territories pretty much to themselves. The spurt of construction during the 1850s posed some threats to this general insulation, but none serious enough to warrant rethinking of the basic strategy. However, by 1860 the possibility of fierce competition for through traffic had become a reality; by 1865 it had become a necessity for survival. Behind that transformation lay a combination of geographical factors, strategical considerations, and a rapidly changing economic environment.

The years immediately following the war witnessed a striking reversal in the relative priorities between through and local traffic. On the one hand the urgent need for income heightened the willingness of roads to vie for through traffic just at the time when the total interregional flow of commodities was increasing rapidly. On the other hand, the growing network of available rail and water routes dueled savagely for a share of that traffic and thereby created a competitive situation radically different from the largely noncompetitive nature of local traffic. The dichotomy between the two sources of traffic profoundly influenced the rate structure of every southern road and played a major role in the movement for public regulation.

The gradual shift in emphasis from local to through traffic constituted the most significant factor in postwar southern railway strategy. It deeply influenced the development of large, integrated systems, which evolved not from coherent planning but through a process of piecemeal expansion based upon momentary needs. It stimulated the expansion and consolidation movements characteristic of the 1870s and 1880s. The economic factors behind it affected policy decisions in most companies and often resulted in bitter fights for control. Perhaps most important, the financial difficulties spawned by it led to a change in profit motivation. In 1860 most southern railroad managers sought to realize profits through efficient operation of the property. By the late 1880s, though, the operation of most southern roads had ceased to be profitable. The source of individual rewards then shifted to manipulation of the road’s financial structure, often to the detriment of the company.

During the period 1865–73 the basic framework of competition for through traffic emerged clearly. In broad terms both interregional and intraregional traffic moved along three basic trade routes. The first of these travelled north and south along the Mississippi River. A second route traversed the cotton belt on a northeast-southwest diagonal between Washington and New Orleans, while the third, lying perpendicular to the second, connected the Ohio-Mississippi river system to the southeastern seaboard ports. North of the Ohio River, the east-west trunk lines hauled freight to northeastern ports for transshipment to the South. Along each of these basic routes there arose numerous combinations of all-rail, rail- water, and all-water carriers eager to vie for southern freight.

The proliferation of combinations along these routes spawned four distinct arenas of competition for through traffic. The first of these pitted the Mississippi River carriers and railroads against each other. Despite the frenetic growth of the railway network, river traffic between St. Louis and New Orleans did not decline significantly until the mid-1870s. Since freight rates on the river remained near antebellum levels until about 1873, the water carriers exerted a powerful influence on rail rates. Only during low-water season could the railroads assert their supremacy, and even then the growing use of barges minimized their independence.

A second struggle revolved around the rail and water-rail combinations north of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi rivers. Most of these freight lines sent their cargoes from New York southward to Atlanta. Competition along this route was especially cutthroat because of the seemingly limitless number of possible combinations. But the high stakes, consisting of cotton moving north and manufactured goods south, provided ample rewards for victorious lines. Most of this traffic went by water from New York and other eastern ports to any one of several South Atlantic ports and thence to Atlanta by rail. A portion of it travelled an all-rail route along the seaboard, but the lack of unified, efficient through service hampered this route.

The third arena of competition, closely related to the second, centered upon the huge grain and other foodstuffs traffic of the Midwest. Competition for this business evolved at two separate levels. The first involved the efforts of all-rail routes along the northwest-southeast axis (including the L & N) to dominate the shipment of grain, flour, meat, and other products into the South. Rivals for this freight included the various north-south routes on both sides of the Appalachians and eastern rail- water-rail combinations. The latter easily proved the most formidable contenders. The east-west trunk lines hauled their cargoes to northern ports, where they were dispatched on coastal steamers to southern ports and then carried inland by rail. Despite the apparently fatal roundabout nature of the route, it dominated the flow of traffic and resulted in fierce rate wars. At the same time, the east-west trunk lines pulled an ever- increasing amount of the grain traffic away from the north-south lines to New Orleans and Mobile. This diversionary influence could not help but wreak havoc on rate structures throughout the South.

The final major competitive struggle centered upon the various all-rail, rail-water, and all-water routes within the South itself. From a regional point of view these clashes were the most severe, for they involved the ambitions of leading commercial centers to dominate markets and establish themselves as gateways. In addition to the contest between Louisville and Cincinnati there were bitter rivalries between New Orleans and Mobile, Atlanta and Montgomery, Savannah and Charleston, and among the South Atlantic ports in general. Occasionally an outside line could enter the struggle as well. For example, the L & N had to contend with freight moving down the Illinois Central to New Orleans and then to Montgomery by rail. Traffic also reached Montgomery from Mobile after shipment to the latter point on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

In most cases the construction of a new railroad served to create at least one new competitive combination. The postwar spurt of construction, coupled with the spiralling need for through traffic income, virtually revolutionized rate structures in the South. For reasons already mentioned, the South had consistently higher tariff rates than northern roads, even though its rates declined steadily after 1850. A high rate structure pertained to local traffic, however, and depended upon the lack of competition. This vital premise disappeared entirely in the quest for through traffic, where cutthroat competition made it impossible for any one line to control its tariff or stabilize the rate structure. Though southern managers chafed bitterly at the wild fluctuations, they had the choice of either submitting to the mad scramble or surrendering any claim to through traffic. For most roads this was no real choice.

The erratic behavior of through rates made it virtually impossible to predict even approximate income from through business. That uncertainty in turn prompted managers to evolve a controversial view of the relationship between through and local business. Local traffic must necessarily remain the primary source of income for the company, and rates for it could be kept stable and relatively high. Through business then became a sort of marginal income upon which the company could not rely. It could be obtained only by offering much lower tariffs, and so the structure of through rates would bear no logical resemblance to that of local rates. To fill empty cars (a crucial factor in the lopsided flow of southern traffic), the road would be willing to offer extremely low rates. Since through cargoes usually went into already scheduled (and unfilled) trains, little extra service was needed. Any added income garnered from this business increased the company’s overall take and might even permit a reduction in local rates. In this indirect fashion local customers would benefit from the battle for through business.

From this rationale emerged one absolutely essential principle: that the two tariff structures, local and through, bore no logical relationship to each other. Local rates derived from a calculation of the cost in providing transportation service plus a reasonable profit. As essential income it could largely be controlled by the company and could not slip below the cost level without threatening the road with bankruptcy. Through rates were based not upon rational calculations but upon the competitive situation at any given moment. They were determined not by the company but by the marketplace. If forced to depend upon through traffic as a primary source of income few railroads could survive. As a source of marginal income, however, the business proved important and indirectly might nudge local rates downward. In any specific situation, though, the road faced the simple choice of accepting through cargoes at the going rate or withdrawing from the business entirely.

Unhappily, this rationale was extremely difficult to sell to the public in general or to irate local customers in particular. Regardless of how reasonable or truthful the explanation, the discrepancies between the two rate structures offered a choice target for critics of the railroads, as did the practices generated by the emergence of through business: long-short haul discriminations, the basing point system, the growing complexity of freight classification, the use of separate terminal charges and joint-line differentials, prorating agreements with water lines, and the establishment of carload and less than carload rates.

The total impact of these issues drastically altered the postwar economic environment. It intensified the already virulent disputes between the carriers and local-interest groups. The fact that certain community interests dominated the management of most roads did not mean that any road served all local interests satisfactorily. Indeed no line could possibly do so because of the conflicting goals held by local-interest groups. As a result disputes arose not only between interest groups in competing cities but also among groups within each city. These conflicts eventually made it evident that a railroad’s corporate goals often differed sharply from those of civic-interest groups.

In surprisingly short order this labyrinthian web of conflicts was transmuted into a host of live political issues. The result would be a successful campaign for public regulation of the railroads, which itself wrought a significant change in the economic environment. In the oversimplified political rhetoric of the era these clashes were described as occurring between the “selfish corporations” and the “public.” In reality, however, the public active in the struggle consisted overwhelmingly of various interest groups deeply affected by the economic impact of the railroads. They ranged from civic leaders of communities seeking commercial supremacy to such economic and occupational groups as farmers, merchants, manufacturers, distributors, and other major shippers. Nevertheless, the agitation of such groups profoundly affected the policies of every company and did much to shape their corporate destiny.

Finally, the growing importance of through business reduced southern freight rates to a state of chaos. A rather perverse equation developed from this unsettled milieu: the desire of carriers for more through cargoes grew in inverse proportion to their ability to stabilize rates. This atmosphere of unbridled competition left its own great imprint upon policy making. It fostered an almost desperate desire to stabilize rates through any of several possible mechanisms, most of which revolved around expansion policy. The need to assure stable through routes forced managers to reconsider the territorial concept. As an integral part of traditional policy they could not easily disavow it, nor did they wish to. Unable to abandon the old strategy entirely, they tended to recast it into the notion of an enlarged territory suitable for controlling a through line but still capable of being sealed off from enchroaching rivals. To achieve this end three alternative tactics seemed possible: cooperation, construction, and consolidation. The primary goals of all three were the same: to achieve stability by monopoly control over rates and to promote an orderly growth pattern.

Cooperation assumed many forms. On the simplest level it involved agreements with connecting lines to promote through traffic at common rates. Sometimes the alliance sought to provide the road with entry into a hitherto untapped territory, but more often it aimed at uniting several companies into a competitive through line. Occasionally such alliances extended to river and coastal steamers. On a grander scale managers attempted cooperation in two vital areas: fast freight service and maintenance of rates. The first occurred with the formation of the Green Line in 1868 and the second with the founding of the Southern Railway and Steamship Association in 1875.

While the Association proved to be the most successful major railway pool, it could not completely stifle rate-cutting and other abuses. Nor could it put an end to competition. As commercial rivalries, aided to some degree by Reconstruction politics, spurred construction of new lines, managers soon realized that cooperation alone was too tenuous a foundation for defense of the territory. Alliances once made could be easily unmade if better opportunities arose. The temptation to eschew long-term stability for short-term profits became especially irresistible to the hungrier roads. The opening of a new and “invading” line tended to alter existing relationships dramatically and to cause a shuffling of alliances. And the stakes were high. Loss of a vital connector meant serious diversion of business and sometimes even a fatal blow to the company.

Fearful of isolation, managers naturally resorted to securing their connections on a more permanent basis. Hence began the growing reliance upon construction and consolidation as methods of achieving stability. Heretofore expansion consisted mainly of constructing small feeder lines to develop local resources; now it came to be seen as the building or acquisition of larger roads to ensure through connections. But such a strategy of territorial expansion, either by construction or consolidation, proved expensive. It often meant passed or reduced dividends; more subtly it meant spending large sums on a business that operated at much lower rates than the staple of local traffic. Stockholders and local shippers naturally demanded to know why their money should be spent to improve service for “foreign” customers, who also received the benefit of lower tariffs.

It was a tough question for managers to field. Perhaps the most striking aspect of their answer was its essentially defensive nature. Most managers conceded freely that new acquisitions would not be a source of direct profit for some time. They had acted from necessity rather than choice, and they sought mainly to protect instead of expand. Additions to the system drained valuable capital and usually brought more problems than benefits to the company, but they were needed to survive in the new environment. Once again, however, the argument fell between the widely spaced stools of logic and self-interest. As a rationale for formulating a new strategy it was reasonably lucid; as a response to the clamor of various interest groups within and without the company it was wholly inadequate.

The postwar development of the L & N followed the model of this broad framework remarkably closely. Indeed, under the astute leadership of Guthrie, Fink, and H. D. Newcomb, the company did not so much pursue this general pattern as it pioneered in the creation of it. For that reason, the general contours of postwar strategy provide extremely valuable insights into the L & N’s early history.

In 1865 the L & N possessed a railroad in relatively superior physical condition, a secure financial status, top credit standing, and an undefined future. During its short life the company had functioned primarily as a local road and done quite well at it. For the more conservative directors, that same pattern of success held the key for future strategy. They advocated a continuing emphasis on local business, a minimal outlay of capital on expansion, and the maintenance of a high dividend rate. As part of their program they suggested a relatively isolationist policy toward neighboring lines.

Opponents of this viewpoint certainly had no quarrel about the desirability of high dividends or close attention to local business. But they insisted that a changing economic environment precluded exclusive attention to those goals and required a careful selection of priorities. Moreover, they added, the new environment demanded a fresh strategy to cope with its problems, and any new strategy would place a heavier demand upon the company’s resources. Under this strain not every corporate goal could be pursued with equal vigor; critical choices would have to be made in the allocation of resources. Invariably the company “progressives” gave territorial expansion their top priority and attempted to divert large amounts of capital to its pursuit. Only in this fashion, they argued, could the road’s territory be defended successfully, its business increased, and the future made secure. In short, they linked future prosperity directly with expansion and the need for through business. Any other course, in their thinking, would lead to decay and competitive suffocation.

The formulation of L & N postwar strategy fell largely to Fink and Guthrie. While it would in later years be referred to as “Mr. Guthrie’s policy,” Fink became its most articulate spokesman and doubtless played a leading role in its genesis. In his annual reports to the company Fink detailed his overall strategy and the tactics necessary to achieve the desired goals. In them he also lobbied earnestly for acceptance of his position by the stockholders. Despite considerable deep-rooted opposition and occasional open rebellions, the genial giant succeeded in persuading the directors to implement his strategic thinking for more than a decade. For that reason and many others, Fink deserves recognition as the man most responsible for the L & N’s destiny in the late nineteenth century.

Albert Fink, engineer and strategist who did more to shape the early destiny of the L & N than any other individual.

Even before the war ended Fink perceived the rising importance of through connections, and he geared his strategic thinking around that basic principle. In his mind the mere desirability of the unbridled competition for through business was no longer a relevant question. The volume of business would grow at a startling rate, and with it the ferocity of the struggle, regardless of any company’s feelings about the matter. The real question, then, concerned the most feasible response to this new development. An orderly program of territorial expansion seemed to Fink the best long-term solution. If it acted quickly enough, the L & N could use its superior postwar strength to good advantage. Delay coúld only fritter away any edge the company had over its recovering competitors. In 1865 Fink openly launched his crusade for territorial expansion.

The existing state of through connections, or lack of them, helped strengthen Fink’s arguments. No rail line linked Louisville to Cincinnati (a situation that pleased many Louisville merchants), and the Ohio River Bridge to Jeffersonville was still under construction. Conditions south of Nashville were even more unsatisfactory. For through traffic to Atlanta and the Southeast the L & N depended upon its connection with the Nashville & Chattanooga. The management of the Tennessee road, however, had taken over the Nashville & Northwestern as well. In an effort to divert through business to the latter road, the N & C openly discriminated against the L & N. It delayed Louisville cargoes and plagued them with various subtle hindrances. More obviously it forced the L & N to break bulk at Nashville and charged the company ten dollars per carload for use of the half-mile road between the depots, a charge equal to the cost of transporting the same carload over forty-three miles of the L & N. At the same time, through freight from the Northwestern went through Nashville without break of bulk or any transfer charge. Understandably this situation provoked loud protests from shippers in both Louisville and Nashville.

Shrewdly Fink played upon these and other complaints against the N & C to push his primary expansion project: extension of the Lebanon branch. That branch remained essentially a local spur line, although as early as 1863 Fink and Guthrie had envisioned its potential as a connector for through traffic. Despite the continued extension of the road late in the war, no authorization for constructing it to the state line had been obtained. Such a project would require an outlay of nearly $3,000,000, but Fink insisted that the investment would pay enormous returns. In pleading for approval of the project he organized his arguments around three major points: that the extension would eliminate dependence upon the N & C south of Nashville; that it would open the rich coal fields of eastern Kentucky to the company; and that it would complete the great Northwest-Southwest through line envisioned thirty years earlier by the visionary Cincinnati & Charleston project.

In glowing terms Fink painted a rosy future unfolding upon completion of the extension. Together with connecting roads from Chattanooga and Knoxville, it would open a through line to Atlanta forty-three miles shorter than the route via Nashville. At Knoxville the shortest route to Norfolk, Charleston, Wilmington, and the entire Atlantic seaboard would spring into existence once the roads in Virginia and North Carolina finished their work. To conservative directors he put the issue bluntly:

A more direct communication between the North-west and the South-west has almost become a matter of necessity. Louisville is now in a position to establish this connection with much less outlay of capital than any other city, and should not hesitate to avail herself of this advantage.2

Matters to the Southwest also concerned Fink. The Clarksville, debilitated by the war, lacked the means to restore the road to operating condition. Shut out of Memphis for this reason, the L & N offered to run the Clarksville and apply all net earnings to redeeming its debt. The Clarksville refused, however, and for a year the L & N did no Memphis business. Finally the Tennessee road obtained $400,000 in state bonds, surrendered them to the L & N for cash, and began to restore the line. Freight and passengers would soon be able to reach Memphis, but the arrangement was far from perfect. The L & N still had to deal with the Clarksville and the Memphis & Ohio, both of which remained financially weak. And connections with the Mississippi Central Railroad south of Memphis still required the use of seventeen miles of Mobile & Ohio track. These arrangements Fink regarded as entirely too tenuous; he recommended that steps be taken to secure them on a permanent basis.

To the north Fink urged the completion of two key projects: the Ohio River Bridge and a road between Louisville and Cincinnati. The first he considered vital to diverting the flow of midwestern cereals and other goods onto southern lines. The second he advocated for two reasons: it would provide the shortest transportation route between Cincinnati and the Southwest, and it would discourage Cincinnati interests from building a rival line southward through central Kentucky. Realizing that many Louisville interests opposed such a road because they feared it would transform their city into a mere way station, Fink neatly reversed their logic. Construction of the line would bring to Louisville an immense amount of business now by-passing it, whereas failure to build it would drive traffic onto other lines and insure Louisville’s isolation. As matters stood, he observed, existing water rates discriminated against Louisville in Cincinnati’s favor in such a way that only a rail connection could overcome them.

Other projects received Fink’s encouragement as well. He advocated company aid for the railroads seeking to connect Nashville with Decatur, Alabama, and Decatur with Montgomery. He envisioned an all-rail route directly to Montgomery, Mobile, and points along the Gulf Coast to capture the interior markets now dominated by roundabout water shipments to the Gulf ports and rail shipments inland. He advised encouragement of the Mississippi Central’s extension to Humboldt, Tennessee, on the Memphis & Ohio, to eliminate dependence upon the Mobile & Ohio.

Fink spelled out his entire program for the stockholders in 1866 and reiterated it year after year. His reports became part box-score, listing what had already been accomplished, and part polemic, emphasizing what remained to be done. To his credit he seldom strayed from the main issues. Sensing that opponents of his program centered their objections around the cost of expansion and the related issues of through-local rate differentials, he met the questions with a typically trenchant analysis. On the differing rate structures he emphasized the ways in which local shippers benefitted from a large through business. The objections of local interests, he reasoned, were based upon false premises:

They argue—and to those who are ignorant of the principles which govern the case their arguments must appear plausible enough —that the people who contributed their means toward the building of the road should have the preference over those who never furnished a dollar for its construction. Were it merely a question of preference, this should certainly be the case. But in reality the question is this: Shall the through business be secured to the road, or shall it be permitted to pass over other routes? It is evident that if the rates are not made to meet competing lines of transportation, this class of business must be lost to the Company altogether.3

Such a loss would be irreplaceable, Fink contended. It netted the company a substantial portion of its income, much of which was spent in the road’s territory. Thus, distant customers helped make the company a success and indirectly poured capital into the region. Without this income the company must either raise local rates sharply to compensate for it, cut dividends, or perhaps even curtail operations. Therefore, every effort should be made to augment that business by building connecting lines. Fink advanced the basic principle that the greater the volume of business, the cheaper would be the cost of transportation. He noted that the Baltimore & Ohio, operating roughly the same total mileage as the L & N, averaged about $1,000,000 a month in receipts to the L & N’s $250,000. At the same time it cost the B & O less than a cent per ton-mile to haul its freight while the L & N’s cost ran to 2.28 cents.

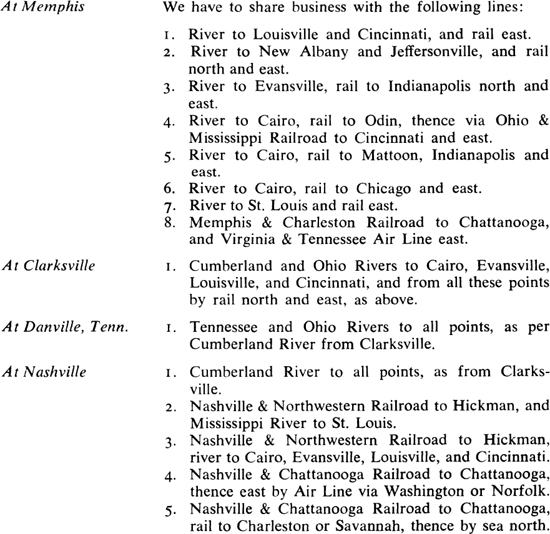

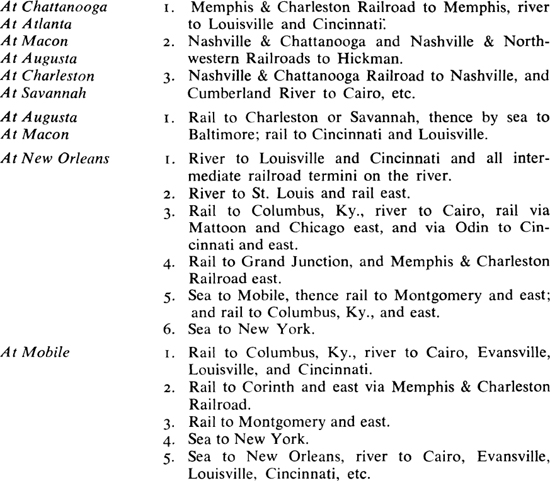

What was needed, Fink concluded, was a greater awareness by the stockholders of the changing economic environment and its influence upon company policy. Especially was this true on the question of the road’s new competitive function: “Formerly a mere local road, doing business between Louisville and Nashville, we are now competing with the various other transportation companies for the through traffic of the entire South.”4 To stress the complex dimensions of that new status, Fink in 1868 listed the existing competitive agencies for the traffic sought by the L & N. His findings are reproduced in Table 2.

TABLE 2

Competitive Agencies for Potential L & N Traffic As Compiled by Albert Fink in 1868

Nor could the tabulation be considered comprehensive, for new lines were under construction everywhere and each new entrant broadened the spectrum of possible combinations. As examples Fink cited three major projects that threatened the L & N’s entire territory once completed: the Henderson & Nashville, the Selma & Dalton, and the Kentucky Central. In advocating his program to meet these threats, Fink did not hesitate to stress their defensive aspects as well:

By carrying out the liberal and far-sighted policy inaugurated under the administration of our former president, the Hon. James Guthrie . . . the interests of the company would soon be placed upon so secure a basis that scarcely any future contingencies could seriously affect them.5

TABLE 2

Competitive Agencies for Potential L & N Traffic As Compiled by Albert Fink in 1868

Source: Annual Report of the President and Directors of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company (Louisville, 1868), 42–43.

In their quest for a winning postwar strategy, the L & N management did not overlook the telling advantage of superior service. If through traffic did represent the wave of the future, expansion policy could solve only some of the many problems involved. Immediate action had to be taken to expedite freight shipments and divert traffic from competitive routes. The most feasible approach seemed to be a cooperative one in which connecting lines provided a joint service to guarantee speedy delivery of cargoes. From this realization arose the fast freight lines that dominated southern shipping from about 1868 to the mid-1870s.

The fast freight lines were created to solve certain problems inherent in the competition for through traffic. Obviously the railroads involved hoped, by combined service, to cut costs and thereby reduce rates below those of competing lines. Equally important, they were designed to permit through service over several roads without the delays caused by break of bulk. Since southern and western agricultural products were especially vulnerable to loss and damage during transshipment, and since storage, insurance, and handling absorbed a major portion of transportation expense, the perfection of through lines offered an immense competitive advantage. Fast freight lines could also increase the rolling stock available for seasonal traffic flow by means of pooling arrangements, and eventually they could simplify customer service by offering joint bills of lading with clearly specified liability assignments.

Predictably, the L & N took the lead in organizing fast freight service for the South. On January 1, 1868, after a series of conferences among several railroad managers, five southern roads established the Green Line Transportation Company. The pool had two major goals: to control freight rates on certain commodities carried by member roads, and to create a system of freight car exchange that would expedite traffic moving between the South and West. The five charter members pledged ninety-six cars to the new organization, to be divided among the roads according to the revenue derived from existing through business between the sections over each road. By this formula the L & N contributed twenty- five cars, the Western & Atlantic twenty-eight, and the remaining three lines forty-three. The administrative structure of the new company consisted of only two officers, a general claim agent and a general agent. It was not incorporated and distributed no earnings or dividends. For policy purposes it created several committees composed of officers from the member lines.

Within a short time the Green Line became the most powerful body in southern freight transportation. By 1873 it contained twenty-one companies boasting a total mileage of 3,317 and included virtually every important southern railroad southeast of the Mississippi Valley. It exerted a near dictatorial influence over territorial freight rates and used its cooperative leverage to discourage ambitious rivals within and without the South. The key Green Line committee, composed of six representatives elected by delegates of the member roads, prescribed rates frankly on the basis of meeting competitive routes. To protect its competitive position the organization did not hesitate to wage ruthless rate wars in which vanquished foes often succumbed to bankruptcy. In addition it worked out reliable car-exchange systems, reapportioned the allocation of freight cars, speeded up shipping schedules, and handled reparation claims for damaged cars and cargoes.

Throughout the Green Line’s brief existence, the L & N dominated its management and therefore its polices. Other southern fast freight lines emerged during the same period, some of which also fell under L & N influence. One such line, the Louisville and Gulf Line, provided through service southwest to New Orleans and Mobile similar to the southeastern service furnished by the Green Line. In each case Fink seems to have played a pivotal role in organizing and administering the operations, and his motives in each case appear to have been the stabilization and improvement of the competitive struggle for through traffic. Southern railroads as a whole benefited from his efforts, as did the L & N in particular. When the Green Line proved inadequate for achieving his goals, Fink pioneered the formation in 1875 of the Southern Railway and Steamship Association, one of the nation’s first and most successful transportation pools.

In responding to the problems of the postwar economic environment, the Green Line profoundly influenced its development. Perhaps its most important legacy was the establishment of guiding principles for the structure of freight rates. The organization based its tariffs on what were known as initial points, which included Cincinnati, Louisville, St. Louis, Chicago, and Nashville. No rate could be made to the seaboard except from these initial points. The rates to interior points such as Atlanta were left to the competing roads, though Green Line members opposed any attempt to undercut through rates by local rates. As a result of these policies, rates to the seaboard were usually lower than those to closer points such as Atlanta. The line also tried to redress the imbalance in southern traffic flow by charging cheaper rates on westbound tonnage than on eastbound cargoes.

The development of Green Line rate structures provided the model upon which the notorious basing point system, which later dominated southern freight rates, would be constructed. The L & N’s management played no small role in shaping that model because it suited the company’s purposes nicely. Through its position of leadership in the Green Line the L & N naturally made Louisville a favored initial point, which enabled the company to discriminate against Cincinnati in the competition for freight moving to the southeastern seaboard. Fourth- and fifth-class freight from Cincinnati to Atlanta were twenty-two and twelve cents higher than the rate from Louisville to Atlanta for only a slightly greater distance. Moreover, by setting lower rates on traffic passing through Atlanta to the seaboard than on freight terminating at Atlanta, the Green Line (and the L & N) deeply antagonized Atlanta’s commercial interests. In later years Georgia’s hostility to the L & N would prove a formidable obstacle for the expanding company to overcome.

The Green Line, and later the Southern Railway and Steamship Association, represented Fink’s most concerted efforts at creating stability through cooperation. The freight line promoted an increase in the number of joint rates between southern roads and between southern and western roads. This stability, along with the improved service it provided, greatly enhanced the competitive position of southern roads. But, like similar cooperative ventures, the southern pools lacked the teeth to insure stability on a permanent basis. No one understood that unhappy fact better than Fink and the officers of the L & N. As a result their quest for stability led them to use the cooperative ventures as a springboard for their version of a final solution: expansion through consolidation and construction.