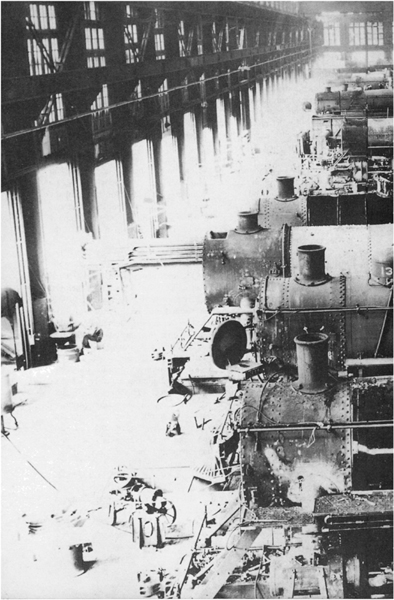

Nos. 196 and 244, both 2–8–0 Consolidation types which first appeared on the L & N in 1883. These engines are standing in the 10th and Kentucky streets shops in this 1888 photograph.

During the frenetic expansion of the 1870s and 1880s expenditures upon the sinews of transportation naturally received a low priority. The defensive scramble for position, the race for new markets, and the short-term profit interests of the financiers all tended to neglect upkeep and equipment. In pure strategic terms the point was to possess or acquire a vital route regardless of what kind of facilities it had or what kind of service it provided. Operational problems could always be handled on a makeshift basis or even through sheer improvisation, especially in a monopolized territory. Obviously survival preceded service, and survival meant expansion. Furthermore, those financiers concerned with transactional profits showed little desire to allocate earnings to equipment and improvements when it might better be used for dividends.

For these reasons, any serious emphasis upon upgrading service and equipment had to await the passing of the speculators. But the unhappy circumstances of their departure threw the company into an awkward position. The combination of expansion and financial embarrassment left the L & N with few resources to allot to a much enlarged system. This dilemma of less funds to cover more mileage meant that betterments would have to be selective and painfully slow. The board readily approved a shift in financial policy that provided more earnings for improvements, but in broader terms even the most conscientious developmental policy could not afford to ignore expansion entirely. Slowly the level of expenditures upon extensions and acquisitions rose, and as they did the flow of funds for badly needed facilities fell off. As a result the L & N slipped from its position of leadership among southern roads. It no longer set the pace, and in fact was by the late 1880s being forced to respond to advances made by rival systems.

In this process the important transitional figure was once again Milton Smith. Here too he resembled a salmon battling his way upstream. During the period 1881–84 Smith persistently advocated an extensive program of betterments. His concept of sound management hinged upon close attention to upkeep of the road, adequate facilities and rolling stock, and efficient service. In 1883 he had forecast a bright future for the company if these policies were pursued (see Chapter 9), but his pleas went largely unheeded. Such projects held little appeal for Newcomb or Baldwin, embroiled as they were in the whirligig of expansion. Their negligence left the L & N in peril after the financial crisis of 1884, for during that year expenditures on equipment and betterments virtually ceased. Once in the presidency, Smith devoted much of his energy to reversing this trend. The result was a continuing uphill struggle against financial stringency, stubborn directors, impatient stockholders, fast-moving rivals, and a variety of other forces in a fast-changing economic environment.

No operational problem illustrated these trends more clearly than the long controversy over converting the L & N to standard gauge. The road’s 5-foot gauge was similar to that of most southern roads but differed from the standard or 4-foot 8½-inch gauge utilized by a vast majority of northern lines. During the earlier territorial era this diversity caused little inconvenience and in fact served useful purposes. Since most roads were originally built to cater to local needs, the commercial interests in their terminal cities encouraged the lines to break bulk there. A direct connection with other roads entering the city would only enable traffic to speed through without stopping and might eventually reduce the terminal cities to mere way stations.

This calamity could be averted in two ways. The town fathers could insure that different roads entering their city did not make direct physical connection, and they could insist that the roads have different gauges. Either condition prevented the flow of through traffic and in fact helped to delineate the boundaries of a company’s territory. This practice was entirely consistent with the territorial strategy and its emphasis upon local markets and local control. The commercial interests of Louisville fought such a battle in 1870–71 when they staunchly opposed L & N control of the Louisville, Cincinnati and Lexington unless the latter road was changed from 5-foot to standard gauge. Only after this conversion was approved, which forced traffic to break bulk in Louisville instead of passing through to Cincinnati, did the L & N obtain permission to make direct connections with the Short Line (see Chapter 5).

As the territorial strategy became increasingly outmoded and inapplicable, so did the rationale behind the diversity of gauges. By 1880 the lack of easy connections had become an anachronism and a positive nuisance. The growing importance of through traffic rendered smooth transfers imperative, not only among southern roads but with northern lines across the Ohio River as well. The fiercely competitive nature of through business forced every major road to seek immediate and effective solutions to the problem. Obviously the intersectional transfers could best be accomplished by bridging the river. Despite the high costs and engineering difficulties, the L & N took the lead among southern roads by constructing a bridge between Newport and Cincinnati in 1870. Fifteen years later it completed a second span at Henderson. Despite stubborn resistance from merchants, tavern keepers, porters, teamsters, hotelmen, forwarding agents, and other vested interests, the cumbersome and time-consuming river transfer was eliminated.

The intrasectional problem did not yield so easily. The suspicions generated by competitive rivalries made agreement difficult on both the desirability of through connections and on the specific gauge to be adopted as common. The cost and magnitude of conversion naturally inclined every company to favor its own gauge as the standard for the region. Years passed with no resolution of the problem. Meanwhile, each road resorted to several expedients to permit interchange of equipment. The most simple was the so-called “compromise car,” which had wheels with 5-inch surfaces permitting it to run over tracks with gauges between standard and 4 feet 10 inches. Although widely used, the compromise cars were disliked by many railroad men who attributed numerous accidents to the broad threads. Moreover, they could not be adapted to fit southern 5-foot gauges. Another device, the sliding wheel, could operate on standard and broad gauges by loosening the wheels, sliding them to a new position on the axle, and locking them into place. The sliding wheels achieved popularity on some northern roads but also proved accident-prone because the wheels were too often fastened carelessly or worked loose in transit.

Disenchanted by these devices, most major southern roads relied upon car hoists or “elevating machines.” Installed at key transfer points, the hoists lifted the car bodies (freight or passenger) so that trucks of one gauge could be substituted for those of another without unloading the cars. By 1886 the L & N alone had steam hoists or similar equipment at Louisville, East Louisville, Mobile, Rowland, Kentucky, New Orleans, Milan, Tennessee, Nortonville, Kentucky, Evansville, and Henderson. The tracks at these junction points contained three or four rails to accommodate cars of different gauges. In the yards beyond were lined row upon row of extra trucks for every needed gauge.

For a time the hoists kept the transfer problem at bay. The trucks of a car could be switched in about four minutes, which sufficed so long as traffic was relatively light. As the volume of business swelled, however, long delays and maddening tie-ups became commonplace. Scheduling delays and complications could divert cargoes to competing lines, and as early as April, 1881, the L & N officers were already discussing the merits of changing to standard gauge. By 1880 nearly 8i per cent of all American railroad mileage could handle rolling stock of standard gauge. Of the remaining trackage, southern 5-foot gauge lines comprised about 11.4 per cent, with the remainder consisting of narrow and miscellaneous gauges. The change would actually involve a shift to only 4 feet 9 inches since standard-gauge rolling stock could traverse that width as well. After considerable debate, the question was left in limbo.

While the L & N hesitated, some of its competitors seized the initiative. In July, 1881, the Kentucky Central converted from 5-foot to standard to conform with the rest of Huntington’s eastern system. Long an advocate of conversion, Smith in September, 1883, strongly urged the L & N board to make the switch by no later than the following June. Still the directors showed little interest and the matter lapsed. In 1884 the Illinois Central’s southern lines adopted standard gauge to conform with the northern end of the system and thereby eliminated its transfer delays at Cairo. The L & N was then immersed in financial woes, but even before the waters cleared Smith returned to the problem. On March 5, 1885, he finally obtained the board’s permission to prepare the change for June, 1886, and to contract for thirty-three new locomotives to ease the problem of converting rolling stock. He estimated the total cost of the change and the new engines at $579,160, a substantial sum for a floundering company.

In short order Smith summoned managers of all connecting 5-foot roads to a meeting in New York on July 31, 1885. Pleading competitive pressure, the Mobile & Ohio had already changed to standard gauge that same month. The ranks of the recalcitrants were dwindling, but the managers of two major lines wanted to postpone any universal conversion for some months. As Smith later confided to the board, “it required some active efforts on my part to overcome their opposition.”1 A committee of six men, including General Manager Reuben Wells of the L & N, was appointed by the executive committee of the Southern Railway and Steamship Association to study the merits of standard versus the 4-foot 9-inch gauge. The committee recommended the latter figure and its report was adopted. On February 2, 1886, representatives of the broad-gauge roads convened in Atlanta to work out the final details. The managers agreed to synchronize their conversion, which would involve nearly 13,000 miles of track. They agreed upon Monday, May 31, and Tuesday, June 1, as the dates for the changeover.

Having won over his fellow managers, Smith pressed his subordinates to perfect the details. To Wells went the task of preparing detailed plans, specifications, and instructions. Once his work was finished the General Manager, J. T. Harahan, would command the operation. There were two broad areas of responsibility: the physical movement of the track, which would be handled by the Road Department, and the conversion of all rolling stock to the new gauge, which would fall to the Mechanical Department. The former would require extra help, additional tools, and some parts. The latter faced a more complex situation. Since most rolling stock bore a relatively simple design, the cars would be converted with little difficulty. Moreover, the L & N had for several years purchased or built its equipment to specifications that allowed its use on narrower gauges. The locomotives presented a more serious problem because of their driving wheels. Some could not be converted and were later sold along with unswitchable cars, third rails, steam hoists, and other displaced equipment.

Since a few L & N subsidiary roads were already standard gauge and could accommodate rolling stock from the 4-foot 9-inch width, the actual trackage to be converted amounted to about 2,000 miles. It was decided to make the change on Sunday, May 30, when the interruption would least affect traffic movements. Harahan mapped his plans as if preparing for a military campaign. Extra help was employed to bring the road crews to a strength of 8,000 men, or about four to a mile. The west rail would be moved three inches east except at points of close clearance such as tunnels, where each rail would be shifted an inch and a half. A week before the change the crews drove new spikes to receive the rail. Since tie plates were seldom used at that time, the change presented few problems except for switches. Old spikes on the inside were removed from alternate pairs of crossties and the shoulders worn into the ties by the rails were adzed off to ease the movement.

Claw bars, spike mauls, spikes, jacks, track gauges, and other necessary equipment were issued to the troops. At difficult points, such as bridges, trestles, or extensive curves, Harahan assigned an extra man to the crew. In both shops and field performance rivalries were encouraged among the men. The company promised cash prizes to the section foremen whose crews made the switch in the shortest time. The foremen in turn offered a barbecue or free drinks or both to their men for a good showing. On some of the less travelled branches the change was made on May 28 and 29 in order to throw a larger force onto the main lines.

As Sunday dawned, all train schedules were suspended and the crews scrambled to their posts. The plan was for each team to move rail until it met the adjacent forces, but this fell victim to the competitive surge. Spurring his troops on with bellows of encouragement, one foreman and his gang changed eleven miles of track in only four and a half hours. The early finishers savored their victory by retiring triumphantly to the water buckets for refreshment while alternately cheering their feat and braying loudly on the glacial pace of the neighboring crews. A holiday atmosphere prevailed as large crowds flocked to the scene to observe the event. By 6 P.M. the essential work was done, the track was tested, and the trains commenced to roll.

The shops performed no less heroically. In twelve hours most of the L & N’s rolling stock was converted and ready for use. One shop alone changed nineteen locomotives, eighteen passenger coaches, 1,721 freight cars of all kinds, and numerous service cars between sun-up and sun-down. It would take another few weeks for the two departments to dispose of the miscellaneous, non-essential pieces and the untouched siding and passing track, but all the basic work was completed on that frenetic Sunday. Good weather favored the work everywhere except near Memphis, where heavy showers slowed the crews. The cost of the change totalled $195,056, with the track absorbing $91,978, locomotives $53,481, and cars $49,577. The sale of equipment rendered obsolete reduced this figure by $29,605.

It was a remarkable performance by any measure, and Smith praised his officers and men lavishly. “Every one directly employed, from the trackmen up,” he reported proudly, “seemed to take a personal interest in accomplishing the work in accordance with the programme, and in a manner to cause the least possible interruption to traffic and inconvenience to the public.”2 Some men in the Road and Mechanical departments had even contributed the day’s work to the company without pay. Unfortunately the board proved unequal to the generosity of its employees. Through an incredibly inept oversight in labor relations or simple courtesy, the directors neglected to adopt any resolutions of thanks or recognition for the personnel involved. Rankled by this lack of consideration and diplomacy, Smith was urging the board to take action four months after the event. “It might have had a somewhat better effect if this had been done soon after the work was performed,” he observed sourly. “I think, however, it would still be appreciated.”3

The belated change of gauge integrated the L & N with the other major systems in the South and in the nation as a whole. The effect was to neutralize a host of logistic and operational problems as factors in the competitive struggle for business. In the long run, of course, it would help speed the effort to eliminate serious competition among the larger systems and substitute for it a policy of cooperation. Every step toward integration served to reduce the number of variables from which some competitive advantage might be gained. A decade later steps were taken to complete the change of gauge. In October, 1896, the American Railway Association’s committee on standard wheel and track gauges recommended that all member roads adopt standard gauge. When 195 of 242 roads, including the L & N, approved the recommendation, Smith directed that the company’s lines be moved the remaining half inch. The change occurred gradually and was apparently completed in 1900.

Another conspicuous change marked the L & N’s integration into the national railroad system: the adoption on November 11, 1883, of Standard Time. Previously all roads based their operatons upon the solar time of each community along its line. Based upon the sun’s passage across the meridian, solar time varied according to the season and so provided no reliable basis for schedules. Sun time in two villages only a few miles apart might vary by several minutes. In an earlier era of small independent lines, the time problem could be dismissed as a nuisance, but the rise of vast systems reaching into every corner of the South created a much different situation where the time differences were multitudinous and irreconcilable. To bring order from chaos, railroads were forced to select one or more local solar times as standard and gear all operations to them. Obviously this posed more serious difficulties for east-west lines, some of which had to use as many as a dozen different solar times as standards for their schedules.

From the beginning the L & N based all its operations on Louisville solar time. Rule 27 of the timetable issued in September, 1858, instructed all engineers and conductors to synchronize their watches with the clock in the Louisville depot, which was designated as standard time. As the system expanded, however, this became an impossibility. Problems multiplied and missed trains and connections became commonplace. Since the dilemma embraced every major American railroad, leading railroad men summoned a convention on the subject in October, 1883. Held in Chicago, the General Time Convention adopted a plan for standardizing time. The United States and Canada were divided into five zones called Intercolonial (now Atlantic), which covered the eastern Canadian provinces, Eastern, Central, Mountain, and Pacific. The latter four, which embraced the entire United States, were calculated upon mean solar time on the 75th, 90th, 105th, and 120th meridians west of Greenwich. The time in each zone differed from its neighbor by precisely one hour.

After this arrangement was approved, all railroads were instructed to set their clocks and watches to the new standard time at exactly twelve noon on November 18, 1883. D. W. C. Rowland, the L & N’s general superintendent, took charge of the company’s preparations. Since the new Central standard time, which covered most of the L & N’s lines, was eighteen minutes slower than Louisville solar time, Rowland took every precaution to avoid accidents resulting from confused schedules. Before the conversion hour he issued a circular to all trainmen and operating department personnel explaining the procedure to be followed:

Should any train or engine be caught between telegraph stations at 10:00 A.M. on Sunday, November 18, they will stop at precisely 10:00 o’clock wherever they may be and stand still and securely protect their trains and engines in the rear and front until 10:18 A.M., and then turn their watches back to precisely 10:00 o’clock, new standard time, and then proceed on card rights or on any special orders they may have … for the movement of their trains to the first telegraph station where they will stop and compare watches with the clock and be sure they have the correct new standard time before leaving.…4

Like the gauge change, the time switch went smoothly. Nearly all the communities on the L & N’s lines adopted the new time, as did the federal government even though Congress did not officially recognize it until March, 1918. The plan approved at the Chicago convention remains the basis for standard time even today. It met with universal approval throughout the nation and drew only a few disgruntled protests from such critics as one northern editor who preferred to run his watch on “God’s time—not Vanderbilt’s.”5 A decade later, in 1893, the L & N went one step further by adopting standarized inspection and maintenance of all timepieces. Never questioning the ineffable handiwork of Almighty God and the majesty of His solar system, Milton Smith was nevertheless willing to improve upon it wherever possible if it increased business efficiency.

Like other aspects of the company, the L & N’s rolling stock expanded tremendously between 1880 and 1920 and in the process lost much of its individualistic flavor and colorful personality. As the stables filled, the new breeds grew ever bigger, stronger, and more specialized. The depersonalization born of rapid growth permeated the yards no less than the administration. Locomotives had long since surrendered their names for numbers, freight cars proliferated far beyond the level of individuality, and service cars retained a semblance of identity derived almost entirely from their specialized functions. Only some of the passenger cars resisted this trend for a time, but then passenger traffic was never very popular with the Smith administration.

The new era especially affected the iron ponies. In an earlier era the perky little 4–4–0 American locomotives and even the 2–6–0 Moguls managed to preserve an aura of distinctiveness through their design, their emphasis upon adornment, and the tradition of assigning an engineer to one particular locomotive. Often embellished with brass and other trim, the early Americans and Moguls usually received loving attention from their operators. The vital task of polishing the brass fell to the fireman, who risked a storm of wrath if he neglected his duty. But the close relationship between engineer and locomotive faded steadily as the stable expanded. Moreover, the newer, heavier engines were more utilitarian and austere. They bore the stamp of managers increasingly bedeviled by costs and less interested in color or personality. Brass trimming or wood paneling did nothing to improve performance and so were jettisoned along with painted wheels and diamond or Laird-type stacks. The handwriting was well on the wall by the early 1880s when the parsimonious Hetty Green was reputed to have lectured Smith for his extravagant use of brass on L & N locomotives.

The new breed of iron horses were heavier, more rugged, and moved relentlessly toward standardization of design. During the late nineteenth century the L & N never achieved even a semblance of uniformity among its motive power simply because many of its engines were secured when other lines were acquired. However, virtually all the locomotives purchased or built by the company after 1880 conformed to a few standard types. One of these newcomers, the 2–8–0 Class-H or Consolidation engine, made its debut on the L & N in 1883. Designed for heavy freight hauls, the Consolidations were the first major retreat from the sprightly iron ponies of the L & N’s early years. Brutish and coldly utilitarian in appearance, they were neither handsome nor glamorous except in their performance. The Consolidations developed 25,000 pounds of tractive force compared to 22,000 pounds for the Moguls and were characterized by their long fireboxes and rather short boiler barrels. The L & N purchased them and also produced a large number in its own shops. Some of the home-made Consolidations were among the first American locomotives to utilize the Belpaire fire-box, which remained standard until the radial stay type replaced it around 1903.

While the Consolidations dominated freight service, a new 10-wheeled locomotive gradually displaced the Americans on major passenger runs. The L & N purchased its first lot of these 4–6–0 Class-G engines in 1890 from the Rogers Locomotive Works. They boasted driving wheels with a diameter of sixty-seven inches and developed a third more tractive force than the heaviest Americans. The L & N brought modified versions from several manufacturers, culminating in an order of eleven Class-G locomotives from the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1903. Subsequently designated as Class G-13, a few of the Baldwin engines remained in use until the 1940s. One earlier Baldwin ten-wheeler, No. 500 or “Queen Lil” as the crews called it, was built for the L & N in 1897 and exhibited at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. After rebuilding and renumbering, “Queen Lil” ran in local passenger service until 1937.

Nos. 196 and 244, both 2–8–0 Consolidation types which first appeared on the L & N in 1883. These engines are standing in the 10th and Kentucky streets shops in this 1888 photograph.

The Consolidations and the G-13 ten-wheelers dominated L & N motive power at the turn of the century. The two types were in fact closely related, but the former proved more enduring. Embodying several improvements and modifications, the Consolidations were turned out in large numbers by Rogers, Baldwin, and the company’s own shops. Some of the later models, the H-28, H-28A, H-29, and H-29A, had superheaters, utilized Walschaerts valve gear, developed tractive forces reaching 49,000 pounds, and carried eighteen tons of coal and 8,500 gallons of water. The South Louisville shops built ninety-four of these models between 1911 and 1914, and the H-29A remained the L & N’s most powerful freight engine until World War I. In 1914 a new freight locomotive, the 2–8–2 Class J-1 Mikado, made its first appearance. The early Mikados boasted a tractive force of 57,000 pounds or 16 per cent more than the H-29A Consolidations. During the war years the South Louisville shops turned out sixty-two of this model. A later version, the J-2A, built in 1921, was the first locomotive built at South Louisville with stokers, though nearly all the Mikados were later so equipped.

No. 1480, a 2–8–2 J-2 Mikado. Designed and built by the South Louisville shops between 1914 and 1921 (the largest class of locomotive ever built at South Louisville), these monster engines were used to haul coal in southeastern Kentucky.

Heavy 4–6–0 G-13 built by Baldwin in 1903. Used on passenger runs, this class represented the ultimate development of the 4–6–0 type.

A more powerful passenger locomotive, the 4–6–2 Class-K or Pacific, first emerged in 1905. The Pacifies had 10 per cent more tractive force than the ten-wheelers and soon displaced the latter on major speed runs. The L & N bought its first five Pacific locomotives at Rogers and then constructed forty more at South Louisville between 1905 and 1910. Like the freight engines, the Pacific went through several models before 1920, culminating in the K-4, K-4A, and K-4B locomotives. Even later versions, the K-5, K-7, and K-8, were built by Baldwin and the American Locomotive Company. Together the later Consolidations, Mikados, and Pacifies remained the L & N’s most powerful locomotives until the postwar (and post-Smith) era.

Rolling stock underwent the same strengthening of the breed. By the 1890s the early wooden freight cars with their small ten or fifteen ton capacities were being replaced by larger models capable of hauling twenty to thirty tons. In 1874 manufacturers first began to use iron or steel underframes in freight cars, although the first steel-framed superstructures did not appear until about 1908. Six years later the L & N erected an adjunct shop at its South Louisville installation solely for the building and repair of steel freight and passenger cars. The heavier, stronger cars carried larger payloads with less damage and loss.

Not only were the new cars heftier and more durable, but they came in a greater variety as well. Crude refrigeration cars had been around for some time but usually consisted of a boxcar with a mound of ice heaped on the platform in its interior. Later models used double sides and doors packed with sawdust for insulation, but the chill still came from a box filled with ice and placed inside the door. In about 1871 the ice was shifted to bunkers at both ends of the car. This arrangement, improved and modified, ushered in the modern refrigerated car. A decade later Alonzo C. Mather, a Chicago businessman, patented his Mather Palace Stock Car equipped with feeding bins and watering troughs. Mather was primarily interested in relieving the suffering of cattle on long journeys, but cattlemen and packers alike quickly saw other advantages in maintaining the weight and health of stock enroute to market.

First L & N 4—6–2S or Pacifies: Numbered 150–154, they were delivered by Rogers Locomotive in 1905. Company shops duplicated the design in forty more Pacifies built between 1906 and 1910.

Another specialty car, the tanker, was also improved and put to new uses. The first Pennsylvania oil carriers consisted merely of wooden tubs fastened to flat cars. In 1868 the first crude horizontal tanker fitted with a dome was introduced, and by the 1890s the improved tank cars carried vinegar, tar, molasses, milk, and other products in addition to oil. Coal-carrying cars, a vital piece of rolling stock for mineral roads like the L & N, had been around since the antebellum era, but by the 1880s the first all-metal hoppers were being built. Gradually their capacities increased, reaching up to fifty tons by the 1890s. Similar improvements were made on other specialty cars. Only the staunchly traditional and familiar caboose retained the same basic design it had assumed during the Civil War.

Many of the specialty cars were developed by firms or individuals outside the railroad industry. Stung early by investment in specialty cars that quickly became obsolete, railroads grew reluctant to risk large sums in their development. Their sluggish response to an urgent demand led increasingly to an arrangement whereby private shippers provided their own specialized cars. In this way a substantial amount of rolling stock was privately owned and therefore supplemented the road’s own collection. The reasons for the trend varied in each specific case. Most tank cars belonged to private firms because some railroads suffered an unhappy experience investing heavily in an early model, the Densmore car, which was rendered obsolete in only four years. When the railroads balked at providing tankers, private shippers furnished them and thereby cut their transportation and distribution costs.

The refrigerator car also confronted railroad obstinancy. Many roads at first refused to invest in refrigeration because they feared disruption of their stake in the shipment of live cattle, which included stock cars, terminals, and stockyards. Southern roads were more amenable to experimenting because they envisioned a large potential traffic in fruits, vegetables, and other perishables. Nevertheless, most refrigerator cars were in private hands until early in the twentieth century, when numerous railroads ceased their opposition and acquired their own refrigerator cars either directly or through subsidiary firms.

Coal cars, too, fell into private hands at first, but for a different reason. Since most mines could not store their coal economically, it was imperative that the operators have an adequate supply of cars at all times. Coal moved directly from the shaft through the grading and processing operations into the waiting cars, which meant that if the cars ran out the mine might well have to shut down. The railroads were perfectly willing to furnish these cars but could not always keep pace with rising demand. Larger operators soon began to acquire their own car supply, which in turn gave them a decided advantage over smaller competitors at times when cars were in short supply. This problem plagued the L & N more than once before the federal government passed legislation in 1920 requiring that in times of shortage all cars supplied to a mine be counted against its quota, whether the cars were privately or railroad owned. After 1920 the number of privately owned coal cars declined steadily until 1963, when the emergence of unit trains reinvigorated the practice.

Passenger cars developed in the opposite direction from their freight counterparts. Their design and layout shifted from austerely functional to the luxuriousness of what Kincaid Herr called the “Victorian fecundity of ornamentation.”6 The retreat from Spartan accomodations commenced in 1887, when the L & N first experimented with enclosed vestibules. The early models proved impractical but in 1893 a wider version, similar to that still in use, was introduced. The wide vestibule utilized an anti-telescoping feature still basic to coach construction.

In 1887, too, gas lighting began to replace the kerosene lamps. Twelve years later the first axle generators and storage-battery systems for car lighting went into use, and the gas lamps gave way to electricity. By 1903 the first patent had been secured on a vapor system of steam heating, which converted steam from the locomotive into steam at atmospheric pressure and thus eliminated the hazard of high-pressure heating. The earliest steam heating systems had arrived around 1881 but were subject to scalding accidents when pipes burst under pressure. Not until the 1920s would a thermostatic control device for vapor heating be devised. In 1893 the first air-pressure water systems were installed; the original design was modified several times over the years. During these years padded seats, carpets, and other accouterments were gradually added to some passenger cars.

While still no den of comfort, the passenger coach had come a long way from its counterpart of 1870. That vehicle was built entirely of wood, weighed about 50,000 pounds, and carried some sixty passengers. In 1879 steel-tired wheels began to replace the older cast-iron ones, and by 1912 the solid wrought-steel wheel was being used. Experiments with all-steel underframing, center sills, and platforms were attempted at the turn of the century. Eight years later the first all-steel cars were adopted, although the L & N did not acquire any until 1913.

The L & N’s dining-car department was born in 1901 when the company purchased three wooden models from the Pullman Company. Equipped to seat thirty patrons and placed on main line passenger runs, the early diners served 57,908 meals in their first year of operation with a staff of one steward, two cooks, and three waiters. The company added new diners slowly, by both purchase and construction, and acquired its first all-steel diner in 1914. Seating capacity for diners was standardized at thirty-six in 1921. For a time, between 1901 and 1905, the L & N also operated four café cars. These proved popular but were converted to full diners in 1905, although the company ran cafeteria cars during World War I. These cars catered largely to troops and were capable of serving complete meals utilizing the soldiers’ own mess kits.

The L & N’s contract with the Pullman Southern Car Company in 1872 guaranteed the latter exclusive parlor-and sleeping-car privileges on the company’s lines for fifteen years. Before the contract expired, Pullman Southern was absorbed by the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1882. The latter was in turn succeeded by the Pullman Company in 1899, which held a virtual monopoly on sleeping cars throughout the American railroad system. The models used on the L & N in the late nineteenth century featured facing sofas that served as seats during the day. Herr described the transformation into sleeping accommodations thusly:

At night, the sofa became the lower berth, its lowered cushioned back permitting double occupancy. A partially permanent partition separated the sofas by day and this was made a complete headboard at night by extracting from under the cushions a hinged portion that made a solid wall. There were also upper and center berths, but these were for single occupancy only. The porter pulled out the center berth from above the upper berth, which was hinged, and the former was held in position by slots in the uprights that supported the curtain rods between sections. Both of these berths were “staggered” with relation to each other and the lower berth and it was thus possible for the occupant of each berth to partially see his neighbors… . The conductors of that day insisted that the occupants of the three levels invariably minded their own business.7

Though superior to most southern roads in the quantity and variety of its rolling stock, the L & N perpetually lagged behind the demand for cars. The situation grew critical during the expansion years 1880–84 when most of the company’s resources were devoted to acquisitions. The financial crisis of 1884 brought matters to a head. For some time the board had refused to authorize funds for new rolling stock, and the retrenchment in 1884 led to sizable layoffs in the car shops. Between June, 1884, and February, 1885, for example, the company destroyed 370 cars and rebuilt only thirty-four. Once in command, Smith quickly got the board to approve a gradual increase in the work force to “nearly or quite their full capacity for building freight cars.”8 Even so, the L & N’s supply of freight cars declined steadily from 10,909 in 1882 to 9,967 in 1886 before the trend was reversed.

Part of the problem lay in the decrepit condition of much of the rolling stock inherited from acquired lines. For some years the supply rate barely exceeded the condemnation rate; in 1887, for example, the company added fourteen locomotives and 779 new cars but also condemned eleven engines and broke up 505 cars. The financial squeeze, extension projects, acquisitions, economic depression, and the clamor for dividends all impeded the attempt to replenish the supply of rolling stock. Confronted by a limited purse, Smith had to assign strict priorities and he unhesitatingly funneled most of his resources into motive power and freight cars.

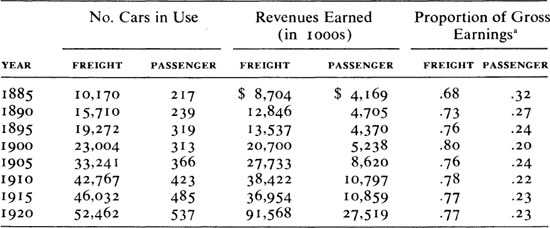

Smith had never cared much for passenger business anyway because, as he was reputed to have said, “You can’t make a g—— d—— cent out of it.”9 What the traveller saw as increased comfort, convenience, and luxuriousness Smith saw as needless expense for a losing cause. He sanctioned the trend toward more opulent passenger accomodations grudgingly and improved the quality and quantity of L & N coaches at a miserly rate. Passenger equipment on many runs was allowed to decay into antiquity. Cursing the segregation statute that forced him to spend money dividing coaches to provide separate accomodations, Smith wrung every possible mile of service from his dilapidated coaches. The result was that passenger business assumed a progressively smaller proportion of the company’s business even though the revenues derived from it increased in absolute terms. Table 4 illustrates this point by showing a comparison of the number of freight and passenger cars in service between 1885 and 1920, the revenue obtained from each source, and the relative proportion of that figure.

Comparative Data on L & N Freight and Passenger Rolling Stock Growth and Revenue Production, 1885-1920

Note: a Percentage of operational gross earnings derived from freight and passenger only; does not include income from mail, express, or non-operational sources.

Source: Poor, Manual of Railroads, 1885–1921.

These figures make clear the L & N’s disinterest in the retreat from passenger business prior to 1915. The demand of war generated an abnormal rise in passenger revenues between 1916 and 1920, and it was no accident that the number of passenger cars operated by the company reached a peak of 653 in 1916 and 666 in 1917 only to fall off to 433 in 1918. Certain new developments during the 1920s caused the L & N to maintain a semblance of cultivating travellers, but the grand withdrawal was already underway. Over the entire period 1885–1920 motive power and freight rolling stock increased at roughly similar proportional rates, as Chart 1 indicates. By contrast the passenger fleet grew slowly and its relative contribution to operational earnings shrank steadily. Except for a few brief and determined spurts, this trend has never been reversed.

The long list of innovations in railway equipment underscored the fact that travel by rail was still considered dangerous in the late nineteenth century. The accident rate was high and the casualties heavy. The causes were many and far-reaching. Simple human error, improper or faulty equipment, and proliferating traffic frequently led to costly rear-end collisions. Bridges built for an era of lighter trains and traffic collapsed beneath unaccustomed loads or from negligent maintenance. Heavier trains and higher speeds imposed severe strains upon obsolete roadbeds and resulted in numerous derailments. Fire usually figured in any wreck with heavy fatalities, whether from kerosene lamps, car stoves, defective wooden bridges, or inflammable rolling stock. The sheer volume of traffic mushroomed so rapidly as to swamp the technology of safety and its human components such as dispatching and signaling.

In the wake of several grisly disasters there emerged a campaign to make rail travel safer. Many roads responded by strengthening or rebuilding bridges, improving roadbeds, and refining the techniques of train control. A closed electric track circuit to set block signals was introduced in 1871. Five years later the invention of manual mechanical interlocking vastly improved train movements by making it impossible for signalmen to line up signals and switches in conflict with each other. This early system was soon supplanted by pneumatic and electric interlocking, but nothing resembling automatic train control emerged until the 1920s.

On the trains themselves the most significant safety innovations were the automatic coupler and automatic air brakes. The benefits of these devices extended to railroad employees even more than to the travelling public. The old link-and-pin coupler harvested a fearful crop of brakemen’s fingers. Technically it could function without the brakemen getting between the cars, but in practice brakemen were too often impatient and couplers obstinate. Hundreds of patents for improved couplers were issued during the postwar era, but none won widespread acceptance. In 1868 Major Eli Janney, a Confederate veteran, patented a coupler whose design he had whittled while clerking in a dry-goods store. The Janney coupler was improved within five years and looked essentially like its modern offspring, but railroads were slow to adopt it. In 1885 the Master Car Builders’ Association began an extensive series of tests on all available coupling designs. Two years later it approved the modified Janney version as standard for the country and urged its adoption.

The early handbrakes posed even greater hazards to brakemen. Scrambling atop the cars, equipped with sand or salt to secure their footing against snow, ice, or rain, the brakemen survived by agility, skill, and raw nerve. The L & N usually carried three of these operatives to a train, which seldom exceeded an average of eighteen or twenty cars in the late nineteenth century. As cars grew larger, the clearance beneath overpasses and on bridges shrank correspondingly. More than one railroad man conceded that hand braking was the most dangerous work in the profession. Well might the profession have hailed the brilliance of young George Westing-house, who patented his first version of the air brake in 1869 at the age of twenty-two. Some brakemen, however, sensed that the new device might put them out of a job. Railroad men were equally skeptical but for different reasons. The legendary Commodore Vanderbilt, visited by the earnest inventor, bellowed in response, “Do you pretend to tell me that you could stop trains with wind? I’ll give you to understand, young man, that I am too busy to have any time taken up in talking to a damned fool.”10

But Westinghouse kept at it. In 1872 he added a triple valve providing air pressure to each car and automatically setting the brake if the train were accidentally separated. By the mid-1880s extensive tests proved the worth of air brakes beyond dispute, but still most railroads hung back because of the large costs involved. At this point an Iowa railroad commissioner, Lorenzo S. Coffin, lent his weight to the fight for increased safety. Moved by a coupling accident in which a brakeman lost the last two fingers on his right hand, Coffin had been crusading for railroad safety since the 1870s. He wrote, travelled, and spoke extensively on the subject, arguing that railway managers refused to equip their trains with the new automatic couplers and air brakes because of the expense. Most managers, he insisted, simply assumed that railroad work was risky and expected their employees to shoulder the hazards.

Coffin’s agitation led Iowa to pass laws requiring all trains to use the new devices. At a national meeting of state railroad commissioners in 1888 he outlined his position and helped mobilize a lobby for safety legislation at the national level. His efforts bore fruit in March, 1893, when President Benjamin Harrison signed into law the Railroad Safety Appliance Act, which required all railroads to equip their trains with automatic couplers and air brakes. The law gave the railroads until January 1, 1898, to comply, but numerous extensions were granted. By 1900 about 75 per cent of the rolling stock had automatic couplers. The emphasis on safety helped reduce the railroad employee accident rate by almost 60 per cent, and passenger safety improved threefold between 1890 and 1915.

The L & N came early to both these devices but equipped its rolling stock at a disappointingly slow pace. As early as 1871, only two years after the patent was secured, the company purchased twenty-six sets of air-brake equipment for locomotives and ninety-four sets for cars. In December, 1880, the L & N installed its first automatic air-brake equipment, and it extended the use of improved versions. But the federal safety act caught the road at a bad time financially. Weakened by the Depression, a yellow fever epidemic in 1897, and other financial commitments, Smith successfully appealed for an extension late in 1897 and again a few years later. Not until 1902 was all L & N rolling stock equipped with automatic couplers. The more expensive air brakes took even longer. By 1905 all but 4.1 per cent of the rolling stock had the new brakes, but it took nine more years to complete the coverage. At that point the lengendary scrambling brakeman passed into history, and once more efficiency replaced color.

The safety campaign extended to the roadbed as well, and here too the L & N had a mixed record. The burden of increased traffic and heavier trains escalated the need for careful road inspection, for replacement of iron by heavy steel rails, and for decent ballasting. Smith had vigorously advocated such a program since the early 1880s, but he got little response from the financiers on the board. In June, 1886, the L & N system embraced approximately 1,757 miles of main stem and 266 miles of lightly travelled branches, not including controlled lines such as the Owensboro & Nashville, Pensacola & Atlantic, Nashville & Florence, and Birmingham Mineral. Of these amounts ninety-nine miles of main stem and an incredible 262 miles of branch lines were still laid with obsolete and badly worn iron rails. If the controlled lines had been included the proportion of iron would have been even higher, since many of these roads were poorly built and had little traffic.

The ballast situation was no better. Despite Smith’s entreaties, management assigned this work low priority. Of the 2,546 miles in the L & N system as of June, 1888, 965 miles were completely unballasted. Only 679 miles of the remainder were fully ballasted, with 601 miles being partly ballasted and 301 miles being secured by sand ballast. Under the Smith administration this work was pressed more energetically with a variety of materials including not only rock and gravel but cinders from company locomotives or adjacent industries, slag from the Birmingham furnaces, chatt, sand, and copper slag from the Copperhill, Tennessee, mines. Even so, it took many years before even main-stem lines were fully ballasted.

The rail-replacement problem went even more slowly despite the best of intentions. Since many of the lines acquired by the L & N had considerable iron on their roadbeds, the elimination of that antiquated metal dragged out interminably. By 1909 only a little more than half a mile of iron track remained in the L & N system—it was located on the Shelby & Columbiana branch of the Birmingham division—but it was not replaced until 1914. The mere removal of iron did not solve the problem, however, for the early steel rails proved too light for the swelling traffic thrust upon them. Some of the original 58-pound steel lasted only about fourteen years and was replaced by 68-pound rails. The L & N ordered its first batch of these heavier rails in 1885 but continued to buy the 58-pound steel until 1891. By June, 1892, the original main stem consisted of seventy-four miles laid in 58-pound steel, seven miles in 67-pound steel, sixty-one miles in 68-pound steel, and forty-four miles in the newer 70-pound steel. Most of the system’s remaining mileage contained either 58-or 68-pound steel.

The Depression delayed further progress for some years, but in 1898 the company laid eight miles of new 80-pound steel. This weight proved so satisfactory that by 1906 about 1,189 of the system’s 4,016 miles were laid with it. The rapid growth of traffic after 1900 brought even heavier weights into service. Some 90-pound steel made its first appearance in 1906 and was placed on 1,791 miles of track by 1918. Even heavier rails were used on small portions of some subsidiary lines, but it was not until 1922 that the L & N first commenced laying 100-pound steel in any quantity. Meanwhile, the lighter weight steels disappeared steadily from mainline routes, and the trend toward heavier rails continued over the ensuing decades. Crossties changed little from the earlier era, though such woods as cypress, red oak, and sap pine began to replace the cedar, black locust, and white oak once used. Although the L & N developed the art of creosoting bridge timbers at an early date, it did not extend this practice to crossties until 1912.

The emphasis upon safety, more durable facilities, and more powerful engines coincided with a heightened interest in speed, particularly on passenger runs. The opening of the Henderson Bridge in 1885, for example, cut the time for the 444-mile trip between Chicago and Nashville to sixteen hours or nearly twenty-eight miles an hour. By 1898 this figure was reduced to less than fourteen hours, and in that same year a special train made the run in an astonishing eight hours and forty-four minutes. The run was made at the instigation of the Chicago Times-Herald to carry a commemorative edition of the paper to the Tennessee Centennial Exposition at Nashville. The L & N joined forces with the Chicago & Eastern Illinois and the Evansville & Terre Haute railroads to provide a special train for the occasion.

Dubbed the Dixie Hummer, the train carried only a small group of railroad and newspaper officials and 200,000 copies of the special edition aboard two baggage cars and a private coach. The engineers were given free rein and all stops were eliminated except those needed for changing engines or taking on water. The Hummer rattled from Chicago to Evansville, where the L & N took over, in 321 minutes for a 288-mile journey. A contemporary pamphlet recounted that “Evansville was reached at 9:23 and at 9:26 Colonel E. H. Mann, superintendent of the division, signalled ‘Billy’ Rowe, the Adonis of the Louisville & Nashville, to give engine No. 33 her head. In the full glory of a southern spring morning the train rolled over the long trestle, over the muddy Ohio and into old Kentucky.”11 Adonis Billy rumbled into Nashville at 12:44, forty-six minutes ahead of schedule and three hours faster than any previous run. His feat caught the Nashville citizenry and welcoming committee still at the dinner table.

As suggested earlier, the faster speeds, heavier rolling stock, and swelling volume of traffic taxed the L & N’s facilities to the limit. One obvious form of relief on the roadbed was the construction of second tracks in densely travelled areas. After considerable discussion the board authorized the system’s first parallel track in 1888, and within two years forty-three miles were built. By the same token, the incessant demand for rolling stock compelled an expansion of the company’s shops. The L & N had major shop facilities at Louisville and Mobile and minor facilities at Bowling Green, Rowland, and a few other points. In 1890 the company opened two new major installations, one at Decatur, Alabama, and one at Howell, Indiana, near Evansville. The two facilities cost the company about $560,000 and did yeoman service, but they could not relieve the glaring inadequacy of the Louisville shops.

The shop situation in Louisville neared the crisis level by 1890. The original shops at 10th and Kentucky streets had been acquired from the Kentucky Locomotive Works in 1858. Several new buildings were added between 1868 and 1872, but the expansion of business quickly outstripped the productive capacity of the shops. To remedy the situation the L & N purchased forty-four acres of land at South Louisville in 1890, primarily for yards to relieve traffic congestion. The Depression blighted any further development, and it was not until July, 1902, that the board authorized the construction of shops on the site. The work was completed in August, 1905, and most of the old structures at 10th and Kentucky were razed.

South Louisville represented a vast improvement over the old facilities. The site housed more than thirty-five buildings on fifty acres of ground, to which was added in 1914 the steel car shop. The original complex cost $2,396,645 and in its first decade of operation produced 282 locomotives, 184 passenger train cars of all types, 400 box cars, 9,430 gondolas, 1,600 coal hoppers, 250 ore cars, 1,200 flat cars, 200 refrigerator cars, 300 stock cars, 300 coke cars, seventy-eight acid cars, and 451 cabooses in addition to the repair and maintenance of existing equipment. South Louisville quickly became the hub of L & N shop activity, but it was supplemented by new major shops at Paris, Tennessee, Etowah, Tennessee, and Boyles, Alabama. In addition, the L & N inherited and improved shop facilities from auxiliary roads at Corbin, Kentucky, Covington, Kentucky, Knoxville, Atlanta, and Blue Ridge, Georgia.

The burdens of expansion affected the officers and paper-pushers no less than the shop and field personnel. By 1890 the L & N’s main office building at 2nd and Main had become hopelessly overcrowded. It had also succumbed to integration of the sexes in 1882, when the company hired its first female secretary. To relieve this congestion the L & N commenced construction in 1902 on an 11-story structure at 9th and Broadway adjacent to the company’s passenger and freight station. Delayed by a steel-workers’ strike in 1905, the new building was not completed until January, 1907. For the first time in decades all of the company’s main administrative staff were brought together under one roof. The edifice cost about $650,000, and remains the site of the company’s offices to the present day, although it has since been enlarged.

Despite Smith’s aversion to passenger business, the travelling public received its share of new facilities during his administration. In November, 1885, the board authorized construction of a new passenger station at Birmingham. Smith justified the expense by noting that all roads entering the city would use this facility and thus share the expense. On the home grounds, the company had purchased land at 10th and Broadway in Louisville as early as 1880 for a new passenger station. Acquisition of the Short Line in 1881, however, caused work to be suspended for nearly a decade. Construction resumed in 1889, and on September 7, 1891, the company formally opened its new Union Station for traffic. Extravagantly praised by the press, the new facility was inspected by a huge throng of curious visitors on opening day. Union Station featured, among other attractions, a novel heating system capable of regulating its temperature by pumping either hot or cold water through the pipes. The station’s location largely determined the site of the L & N’s new office building a decade later. Built at a cost of $310,056, the massive stone exterior with its high clock tower has changed little in eighty years.

The L & N’s other original terminus, Nashville, also received a new Union Station. In 1893 the company joined with its subsidiary Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis to incorporate the Louisville & Nashville Terminal Company. The new corporation was to hold the terminals, depots, tracks, real estate, and other property of the two systems and lease them to the parent roads. The lease became effective in 1896 after some modifications, and was intended as the vehicle for constructing a new passenger station. The parent systems finally agreed on specific terms of the project in June, 1898, but promptly met resistance from the city of Nashville on questions relating to right-of-way and other concessions.

The inadequacy of passenger facilities at Nashville had been notorious for years. For nearly forty years the Nashville had scraped along in a cramped depot built in the 1850s. That situation became intolerable in 1886 when the L & N depot burned down and the latter company squeezed into its subsidiary line’s decaying premises while it sought a suitable location for new facilities. The search dragged on dismally while the railroads, the mayor, the city council, the press, and influential bodies of citizens wrangled over terms. One bill passed the city council in June, 1896, only to be vetoed by the mayor and rejected by the railroads. A bill acceptable to all parties finally passed in June, 1898, and construction began soon afterward.

General office building at 9th and Broadway in Louisville. The original 11-story structure was completed in 1907. The annex, extending the frontage to 368 feet, was completed in 1930.

The new Union Station opened September 3, 1900, to rave reviews in the local press. Designed in the prevailing Romanesque style of the era, it was built of Tennessee marble and Bowling Green stone. The main building was 150 feet square, and the central tower soared to a height of 219 feet. Atop its peak stood a 20-foot bronze statue of Mercury, a leftover relic from the Commerce Building at the Tennessee Centennial Exposition. The usual crowd of spectators flowed through the main waiting room, dressed in light oak and Tennessee marble, and the hall to observe the tinted bas-relief figures above the clocks on the north and south walls. Two young ladies, representing Nashville and Louisville girls, adorned the south wall with outstretched hands. Opposite them on the north wall, two other figures personified the more abstract concepts of Time and Progress.

Progress. That was the connotation, indeed the definition, of every improvement in the sinews of transportation. More facilities, better services, faster schedules, more efficient performance, more luxurious and convenient accouterments, and more handsome appointments—all these betokened the L & N’s obeisance and dedication to the notion of progress so cherished by Americans. Sometimes succeeding, often falling short, and always scrambling to keep pace, the L & N strove valiantly to meet the demands of progress. Like the age itself, the company bore little resemblance to its youthful self of thirty years earlier. Nor would the metamorphosis soon cease, for change was the essential hallmark of progress. The next half century harbored even greater transformations for the sinews of transportation.