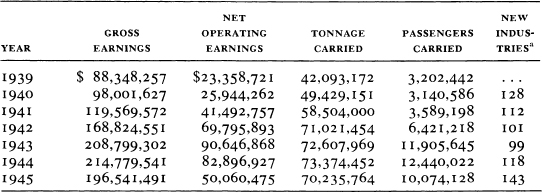

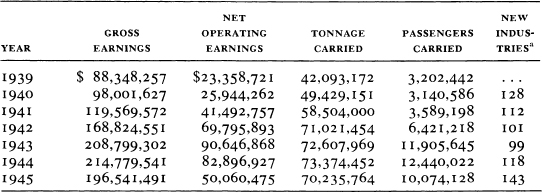

TABLE 6

Selected Data on L & N Operations, 1939-45

Note: a This figure refers to the number of new firms locating along the company’s lines during the year.

Source: Annual Reports of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company, 1939-45.

Like a phoenix risen from the ashes, the L & N shook off the clogs of depression and, under the powerful stimulus of war, achieved performance peaks that would have been considered impossible a few years earlier. Year after year it shattered financial and operational records that had gone unchallenged since the prosperity of the mid-1920s. For a few years at least, World War II solved nearly all the L & N’s major problems. It brought the company more business than could be handled comfortably, drastically reversed the decline in passenger revenues, sharply curtailed the threat posed by the new competitors, and expedited the company’s drive to streamline its operations. Only the worsening dilemma of labor relations resisted the invigorating tonic of wartime conditions, but even here differences were at least ameliorated in the name of patriotism.

Of course the war created its own difficulties and aggravated existing ones, especially in the realm of maintaining or upgrading equipment and physical facilities. But these were minor compared to its positive effects. Once the conflict ended, however, it was widely feared that the inevitable postwar economic dislocation would thrust the L & N (and other railroads) back into that sea of troubles from which it had so recently emerged. The painful experience of 1920-21 had not been forgotten, and the turbulent conditions encountered in 1946 seemed to confirm that suspicion. For a time the road to readjustment looked to be long, tortuous, and uncertain in its destination.

There seemed to be good reasons for these apprehensions. Scarcely had the victory cheers faded when most of the prewar problems reappeared in virulent form. Equity capital was desperately needed but remained scarce to the point of extinction. Rival modes of transportation regained fresh vigor and commenced a period of unprecedented growth. Their impact upon the L & N’s traditional sources of business was profound enough to drive the company into a furious effort to retain old markets and seek new ones. In that quest governmental regulation and taxation policies once more became an intolerable burden to the L & N management. Labor relations assumed new dimensions that made them progressively more critical and costly.

To the unadjusted eye the postwar situation seemed grimly reminiscent of the company’s prewar dilemma. In that context the fight for survival looked to be a discouragingly uphill one. A rampant inflation was developing momentum, and the labor unions had grown powerful and restive. Against these twin pressures on costs the L & N could offer only a feeble response. The rigid federal regulation of rates made it impossible for railroads to react swiftly to rising expenses, and whatever tariff increases the ICC eventually granted could never compensate the company for revenue lost in the interim. Taxation policies, especially the provisions on amortization of equipment, further aggravated the shortage of capital. The bitter competition with other transportation modes underscored the latter’s numerous advantages, such as flexibility, relative lack of regulation, and especially the benefit of public subsidies.

Despite this bleak picture, the times were in fact changing. The railroads would never retrieve their earlier prosperity and superiority, but neither would they suffer the catastrophe of elimination prophesied by many observers. Several factors account for their survival in reasonably good shape. For one thing the postwar years, after the brief trauma of reconversion, ushered in a long term period of prosperity. The railroads gleaned a somewhat unequal share of this economic bonanza but it was sufficient to keep the stronger systems healthy and to buttress them against short-term slumps.

A second factor concerned the nature and sources of this new prosperity. Contrary to expectations the high level of wartime industrial productivity did not fall off sharply after 1945; instead it merely shifted direction to meet new sources of demand. The most obvious wellspring was the tremendous craving for consumer goods that had been unobtainable during the war years. To meet these needs industrial firms in turn required new and replacement equipment which had also been in short supply under wartime priorities. The production stimulated by these demands insured the railroads of a growing base of industrial and manufacturing business. It also reinvigorated the market for raw materials. For example, the astonishing increase in demand for electricity generated a voracious demand for coal, which assured the L & N a thriving business in that commodity.

But consumer demand was not the only stimulus for continued high productivity. Government spending remained at unprecedented levels and increased steadily. Much of the impetus for federal expenditure derived from the uncertain contours of the international situation and the lengthening nexus of American foreign policy. The economic repercussions of defense spending and the expanding concern over national security were to profoundly influence the railroad system. In fact the stimulus of wartime never fully ended; rather it was prolonged indefinitely by the vagaries of the Cold War broken intermittently by the Korean War and, later, the war in Southeast Asia. The phrase “industrial-military complex” had not yet been coined, but the reality it described was to play a vital role in the destiny of the L & N and other major systems.

Together these problems and prospects helped shape a new economic environment for the L & N, one that required readjustment and a redirection of strategy. The era of expansion was long gone, and any strategy founded upon its obsolete assumptions invited disaster. The basic problem now was to meet the massive challenge posed not by rival railroads but by other transportation modes blessed with innumerable competitive advantages. The cornerstone of any new strategy had to be a ruthless quest for efficiency—one that would maximize the railroad’s assets and neutralize its many traditional liabilities.

A strategy based upon efficiency had to begin with a rigorous paring of costs. Labor comprised the largest and most stubborn cost item. Since the strength of the unions guaranteed that the per capita cost of workers would rise steadily, the only alternatives were to fight for changes in the work rules and, more important, reduce the labor force by replacing men with machines. On several fronts, in fact, modernization meant mechanization, whether it be computerization, centralized train control, or a host of other innovations that would revolutionize operational techniques. In each case a large investment in machinery would result in continuing reductions of cost. By the same token huge sums of money had to be spent in enlarging and upgrading rolling stock, and this task soon became the L & N’s primary concern.

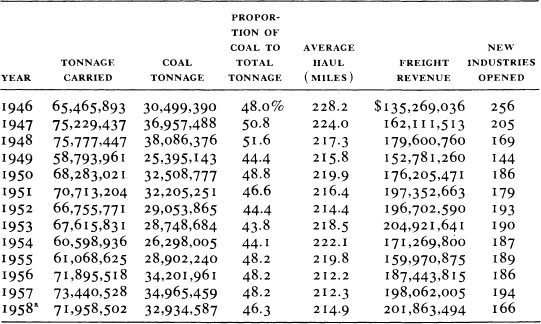

The drive for efficiency extended beyond capital investment. Management sought to refine the company’s techniques in marketing as well as operations. New sources of traffic had to be found, and more sophisticated methods adopted to attract them to the railroad. To remain healthy the company needed to diversify its tonnage. For many years coal had dominated the traffic statistics. It would continue to do so for a long time to come, but in the new era no major system could afford to depend heavily upon one commodity. In the postwar period the declining proportion of coal to other tonnage would serve as a crude measurement of the L & N’s concerted attempts at diversification. Here, as elsewhere, management quickly learned that efficiency and innovation went hand in hand.

While the clouds of war spread across Europe, the L & N was putting its financial house in order. The company’s $69,243,000 unified 4 per cent bond issue of 1890 fell due on July 1, 1940. Faced with some financing difficulties and anxious to reduce the funding debt, management took a somewhat novel tack to the refunding problem. It bought $9,243,000 worth of the bonds with treasury cash and thereby lowered the funded debt by that amount. The remaining $60,000,000 was raised by selling $60,000,000 worth of collateral trust bonds; half of these were 10-year 3.5 per cent bonds and the other half 20-year 4 per cent bonds. The transaction marked the beginning of a decade-long effort to reduce the funded debt and fixed charges.

One piece of national legislation vital to the railroads was passed about this same time. The Transportation Act of 1940 lacked the breadth of its 1920 predecessor, and ultimately it failed to provide the benefits sought by the railroads. The Act made interstate commerce by waterway subject to jurisdiction by the ICC for the first time, but it subjected water carriers to a much looser regulatory framework than that governing railroads. As a result it did little to lessen the advantages possessed by the L & N’s water competitors. Yet the Act did declare as policy its intent to make provision for “fair and impartial regulation of all modes of transportation subject to the provisions of this Act, so administered as to recognize and preserve the inherent advantages of each.”1

By 1940 the L & N was experiencing a dramatic revival of business which management attributed directly to “activity incident to the war abroad and the National Defense Program.”2 New plants and industries streamed into the territory adjacent to L & N lines. These included such diverse installations as the Gadsden ordnance plant; a huge 24,000-acre ordnance works at Milan, Tennessee; an air depot at Mobile; a naval ordnance plant at Louisville; a TVA phosphate drying plant at Godwin, Tennessee; and a flour and feed mill at Decatur. In addition, such industries as Tennessee Coal & Iron in Birmingham, Reynolds Metals in Louisville, ALCOA in Alcoa, Tennessee, Republic Steel in Alabama City, and Ingalls Iron in Pascagoula, Mississippi, rapidly expanded their existing facilities to meet the new demand. Several new military camps and installations also came into the territory and promised a large flow of freight and passenger traffic.

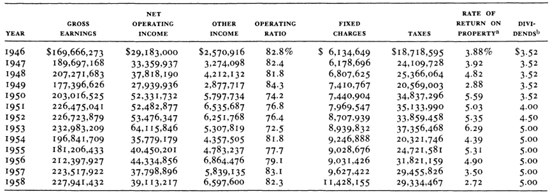

In short order the L & N shook free from the staggering effects of the 1938 recession. The tempo of recovery increased in 1941 as defense spending soared, and after Pearl Harbor it accelerated at a maddening pace. As the data in Table 6 indicates, the company turned in one record-breaking performance after another during the war years.

TABLE 6

Selected Data on L & N Operations, 1939-45

Note: a This figure refers to the number of new firms locating along the company’s lines during the year.

Source: Annual Reports of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad Company, 1939-45.

The effect upon passenger traffic was particularly striking. For these few years troop movements helped to reverse completely the downward trend. Passenger-miles, for example, totalled 2,517,857,634 in 1944 compared to 884,124,595 in 1920. Between 1939 and 1945 the L & N actually reduced its passenger train car fleet from 704 to 587, but much of the loss consisted of obsolete rolling stock. This decline in equipment was offset by a concerted efficiency program. Coaches and diners had their seating capacity enlarged to get maximum use of space. Even seats in lounges and observation cars were sold, and more personnel were added to the dining service. The latter underwent a terrific expansion of business. The prewar record for number of meals served was 642,433 in 1926; in 1943 the company served nearly 2,400,000 meals, 60 per cent more than the previous year and about 400 per cent over 1941. Nearly half this amount was served on government orders.

Operational techniques also felt the effects of the new emphasis upon efficiency. Grades were reduced to permit movement of heavier tonnage, and special trains, known as “symbol” freights and “mains” for carrying troops, were established. The symbol trains were fast through freights hauling only terminal business. Devoted primarily to war materials and designed to run ahead of their schedules whenever possible, they were identified by symbols such as LN-i or ED-7. The “mains” consisted of unusually long passenger trains devoted entirely to troops and were augmented by extra cars added to regular trains. Though the overall service worked well, one such train brought the L & N’s proud passenger safety record to an end. On July 6, 1944 several cars of a long troop train were derailed at Highcliff, Tennessee, killing thirty-five and injuring ninety-one. These were the first passenger fatalities on the L & N since the Shepherdsville wreck on December 20, 1917.

Employment, too, expanded rapidly under wartime conditions. In 1939 the L & N averaged about 28,000 employees; that average rose steadily to a peak of 34,303 in 1945. Some 6,936 company workers went into the armed forces, 112 of whom lost their lives. One unit in particular, the 728th Railway Operating Battalion, was staffed largely by L & N officers and employees and performed creditably in Europe.

Those employees on the home front duplicated their predecessors’ achievements during World War I. The demand for labor and loss of men to military duty brought a fresh composition to the L & N “family.” Many older men came out of retirement to fill vacant positions, and women streamed into the company in unprecedented numbers reaching nearly 3,500 by 1945. Once again the ladies performed as clerks and stenographers, but this time they breached hitherto exclusively male domains as well. Women were hired as agents, ticket sellers, messengers, operators, and draftswomen. Some, known patriotically as the “L & N Wacs,” ventured into the shops to serve as cleaners, sweepers, material handlers, rivet catchers, turntable operators, and engine cleaners.3 The South Louisville shops alone boasted a force of over 200 women.

During the war L & N employees purchased $25,255,000 worth of war bonds through the company’s payroll deduction plan. They put in plenty of overtime, donated blood, served as air-raid wardens, organized car pools to save fuel, and made a host of sacrifices large and small. They participated in scrap drives and joined the company in economizing on the use of priority metals. The shops did more welding to restore worn parts, and substituted iron or steel for copper wherever possible. Such pieces as old axles and journal box wedges were reforged, and efforts were made to reclaim grease and packing.

The vigorous drive for scrap provided a neat stimulus for hastening the abandonment of unprofitable mileage, the fixtures of which could then be requisitioned by the government. Between 1941 and 1945 the L & N cheerfully abandoned about 201 miles of track. The largest portions involved sixty-three miles of the Evansville division, forty-seven miles of the branch between Winchester and Fincastle, Kentucky, the 16-mile Harriman branch, and the 17-mile Swan Creek branch. Significantly, management admitted that the Evansville division mileage, all of which lay in Kentucky, was being abandoned because “prior to 1940 considerable revenue came from the movement of crude oil over these branches which has since been diverted to pipe lines and barges.”4

On the eve of the war years the Hill administration continued to lament the inroads made by publicly subsidized competitors. In 1940 Hill itemized his complaints. Trucks were cutting into the L & N’s movement of cotton, livestock, fruits, vegetables, forest products, fertilizer, and even sand and gravel. Pipelines diverted huge quantities of crude oil and its products. Barges on inland waterways also hauled crude oil along with salt, grain, iron and steel, automobiles, coffee, sugar, and other staples. And, of course, there were the passengers lost to automobiles, buses, and airplanes.

The L & N took several steps to counter this threat. The more obvious ones included such improvements in service as faster schedules, more efficient loading and unloading techniques, and better car placement. With ICC approval a coordinated rail-truck service was introduced into part of the main-line territory. The ICC lent some assistance in September, 1940, through changes in classification that had the effect of reducing rates on more than 5,000 items. Several staples, including fertilizer, sand, and gravel were affected by this reclassification, and rates on forest products, fruits, and vegetables were also lowered.

Ultimately, however, the exigencies of war dramatically strengthened the L & N’s competitive position, at least for a time. To be sure, the need for oil stimulated the rapid growth of a pipeline network in the Southeast. On the other hand, shortages of gasoline, rubber, and vehicles themselves sharply curtailed the activity of highway competitors. Coastal shipping virtually disappeared beneath the submarine threat and the urgent need for ships elsewhere. Air competition still existed but was severely hampered by military needs for aircraft and facilities, to say nothing of pilots. Common carrier traffic on inland waterways declined although tonnage carried by contract and private water carriers increased. Except for the pipelines, the company ceased to worry about its rivals for the moment. As Hill put it in 1943, “competition with busses, trucks and airplanes is at the moment academic because, like railroads, they are handling the maximum traffic the available equipment can accommodate.”5

This welcome reprieve from competitive pressure was but one of the blessings conferred upon the L & N by wartime conditions. The need for maximum efficiency spurred several developments with long-term benefits. In the thorny labor area, for example, the growing shortage of skilled workers intensified the company’s campaign to supplant men with machines. In operations new innovations were adopted, the most important of which perhaps was Centralized Train Control (CTC). This new control method allowed a single dispatcher sitting at a control panel to set switches and signals for all trains moving over distances ranging up to 400 miles. Some railroads had installed CTC as early as 1929, though only 2,163 miles of the nation’s lines were covered by it in 1941. The L & N completed its first CTC installation, covering the ninety-six miles between Brentwood, Tennessee and Athens, Alabama in June, 1942. By the war’s end the company had extended CTC to 400 miles of track and had commenced work on another 137-mile stretch.

Relations with the federal government also proved generally beneficial to the company. Since the roads remained under private control for all but about three weeks of the war, the L & N’s management could etch its contribution to the war effort in sharper detail than in 1918. During the period 1942-45 it paid more than $165,000,000 in federal taxes and spent another $50,000,000 on improving and enlarging its facilities. In return, of course, it received the greatest flow of traffic ever handled by the system. In addition, the L & N benefited from certain tax arrangements instituted during the war crisis. One such provision, section 124 of the Internal Revenue Code, approved February 3, 1941, allowed corporations to amortize over sixty months the cost of any facility certified as necessary for national defense by either the secretary of war or secretary of the Navy, “with a corresponding deduction for income tax purposes.”6 Between 1941 and 1945 the L & N obtained certification for equipment and property totalling $32,864,622.

In some areas the L & N suffered from the exigencies of war. It could seldom procure enough rail and other materials necessary for maintenance. Yet the property was kept in far superior condition than it had been during World War I, and its officers voiced remarkably few complaints. Hill was in fact pleased with the company’s wartime performance, and he did not hesitate to draw the proper moral from the experience:

To summarize the contribution by the railroads of the United States … is but to repeat the abundant praise heaped upon them by military authorities and the public. … With less equipment and fewer employes than during World War I, they carried a much greater volume of military freight and personnel, and at the same time met the demands of a large domestic commerce, all without serious delays, congestion, or embargoes.

Their successful accomplishments in World War II, in which this Railroad contributed its share, constitutes an enduring tribute to the proven system of free, private enterprise.7

Scarcely had he penned these words, however, than he was compelled to acknowledge a discouraging signpost of the future: “The war’s ending caused a disturbing decline in this Company’s traffic.… ”8 The question that faced management in 1945 was simply this: What would be required to restore that business?

The basic contours of the postwar economic environment emerged shortly after the fighting stopped. In broad terms the economic trend could be characterized as prosperity disturbed by severe fluctuations induced by such factors as defense spending on the stimulant side and labor disruptions on the depressant side. A fearful postwar depression comparable to the dislocations of 1921 had been freely predicted by men at every level of business, labor, and government once the wartime demand ceased. Doleful prophecies flooded the popular magazines and more serious media, but the dreaded depression never materialized. Instead there developed quite a different problem—that of rampant inflation.

With impressive haste the emergency economic apparatus of wartime was dismantled after VJ-Day. The War Production Board lifted most of its controls, the Office of Price Administration removed price controls, and federal taxes were sharply reduced. Consumer demand, stoked by full employment, steady wages, and high savings levels induced by wartime shortages, spurred the conversion process with an incessant clamor for goods unaffordable before the war and unobtainable during it. The result was a chaotic year of dislocation in 1946 followed by a surge of economic activity. Freed from OPA restrictions, prices shot upward at an alarming rate. The consumer price index for all items had risen from 59.4 in 1939 to 76.9 in 1945; by 1948 it reached 102.8. Wholesale prices jumped even more dramatically, going from 50.1 in 1939 to 68.8 in 1945 and soaring to 104.4 by 1948.

Price levels stabilized somewhat after 1948 as the backlog of consumer demand diminished, but by 1950 increased government spending, especially in the military-defense area, helped generate another inflationary push. Despite periodic fluctuations, it became apparent that an inflationary trend would characterize the economy for some years to come. This long-term trend posed two serious problems for the railroads. Since their rate structures were tightly regulated by the ICC, they could not readily adjust their income to meet rising costs. This deadly lag in closing the gap between revenues and expenses aggravated the carriers’ already grave difficulty in raising investment capital. Secondly, the inflationary trend added further pressure to that most sensitive cost area, labor. A steadily rising cost-of-living index insured that the railway unions would take a hard line in their demands for higher wages.

John E. Tilford, president from July I, 1950, to April 1, 1959, confronted the difficult problems of adjustment posed by the postwar era.

If the overall economic landscape appeared unpromising for the railroads, the competitive situation looked positively bleak. After VJ-Day the steady flow of traffic and passengers to rival modes of transportation, dammed up temporarily by the war, resumed at a disheartening pace. The number of private automobiles, trucks, and buses on the highways multiplied steadily. Pipelines and barges cut into bulk cargoes, and the airlines, invigorated by wartime technological developments and growing postwar government subsidies for airports and other facilities, emerged as major rivals. Though federal regulation slowly embraced these other forms of transportation, it remained well short of that imposed upon the railroads.

The perils of so treacherous an economic environment required prompt and decisive response from the L & N’s management if the company were to survive. As it had in the past, the L & N received solid, competent leadership during these transition years. Hill remained in the presidency until July 1, 1950, when he gave way to John E. Tilford. A native of Atlanta, Tilford held various positions with the Atlanta, Birmingham & Atlantic Railroad (now part of the Atlantic Coast Line) until 1920, when he became assistant to the L & N’s freight traffic manager. He retained that position until March, 1928, when he was elected chairman of the Southern Freight Association. In February, 1937, he returned to the L & N as assistant vice president in charge of traffic. He moved up to vice president of traffic in 1945 and then to executive vice president in 1947, which put him in position to succeed Hill. Tilford had been a member of the L & N board since 1946. Like most of his predecessors, he had come up through enough offices to be thoroughly imbued with railroading.

The chairman of the board, Lyman Delano, died on July 23, 1944, and was replaced by Frederick B. Adams, who in turn gave way to A. L. M. Wiggins in September, 1948. Born April 9, 1891, in Durham, North Carolina, the son of a plumbing contractor who died when his son was still very young, Wiggins worked his way through the University of North Carolina. After graduation he developed a career in banking and became an executive for a printing company. Railroading formed no part of his background, but he became a successful financier and business executive. In January, 1947, he was appointed undersecretary of the Treasury. He held that post until September, 1948, when he left to accept the chairmanships of the boards of the Atlantic Coast Line Company, Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, and the L & N. Since 1902 the three positions had always been held by the same man, but Wiggins would turn out to be the L & N’s last chairman of the board.

Between 1946 and 1959 the L & N’s management fashioned their strategy for the postwar environment and followed it with remarkable consistency. Its basic tenet was neither original nor very new; it consisted simply of the gospel of modernization and efficiency pursued with unyielding vigilance. Every major L & N officer paid obeisance to modernization as his primary objective, and most of them took the vow seriously. Wiggins summarized the prevailing attitude well when he addressed the L & N board for the first time in September, 1948:

I recognize that the railroad industry faces a difficult future. It must meet the challenge of modernization, efficiency and service or it will die of revenue malnutrition. On the other hand, retained earnings, above reasonable dividends plus depreciation charges, are grossly inadequate for the capital outlays required for plant, equipment, and service. New equity money seems to be a thing of the past. Therefore, it will be necessary to finance some of our capital needs through loans. These loans must be repaid in part out of working capital. Our task and responsibility is to chart a judicious course, looking ahead as best we can and neither let our enthusiasm for needed improvements lead us into a false optimism that will seriously weaken our financial position nor, on the other hand, fail to show the courage that may be required for appropriate action to carry on the progressive development of this railroad.9

The situation was reasonably clear, the difficulties glaring, and the task obvious. Everything depended upon execution.

Any drive for modernization and efficiency had to begin with capital equipment, especially rolling stock, and the postwar economic environment posed special problems in this area. Though car shortages remained an eternal problem, it was no longer merely one of numbers. Technology and industrial diversification were fast changing freight car requirements. Newer engines were capable of hauling longer trains of much larger cars, and young industries with peculiar needs demanded more specialized rolling stock. What the L & N needed to do, then, was not simply to increase its stable of cars; in fact it wished to let older and smaller cars serve out their years without replacing them. Instead the company invested heavily in a select line of modern cars with large capacities. Though not entirely satisfactory, this tactic seemed appropriate to an era where the pace of technological innovation kept shipping needs in a perpetual state of flux.

The figures bear out the L & N management’s faithful adherence to this tactic. Between 1946 and 1959 the company invested $304,514,831 in new rolling stock, most of it financed by equipment trust issues. Yet, as the data in Appendix III shows, the number of engines of all kinds declined from 961 to 733, freight cars from 60,491 to 59,184, and passenger cars from 613 to 545 during that same period. Newer, larger cars and more powerful engines meant considerably more tonnage hauled by less equipment. Only in this manner could the twin goals of efficiency and economy be achieved.

In motive power the L & N gained these results by a slow, deliberate process of dieselization. Despite the obvious advantages and economies of diesel engines, the company abandoned steam power with great reluctance. Such a trend would shrink the market for bituminous coal in which the L & N had a large stake. To forestall that eventuality, the L & N in 1944 joined several other coal-carrying railroads in funding projects designed to develop an improved coal-burning locomotive and even a coal-burning steam electric turbine locomotive. This research continued into the mid-1950s, though by that time it had broadened its scope to include “the promotion of a wider acceptance and use of coal.”10 By 1956 mention of the work was dropped from the company’s annual reports. This was hardly a surprise, for that same year the L & N had retired its last steam engine and boasted completely dieselized motive power.

The crucial decision to go with diesel power seems to have been made around 1949. Prior to that date the L & N had acquired seventy-four diesels but used them mostly as yard engines. After extensive studies, management concluded that “substantial savings could be effected through installation of freight diesel power on the lines between Cincinnati and Montgomery and St. Louis and Nashville.”11 During the next seven years the board intensified its conversion process, increasing the diesel fleet to 596 by 1956. The total cost of dieselization came to approximately $87,000,000.

This rapid transformation created some difficulties. Crash training programs in repair, servicing, and maintenance practices had to be instituted, fuel stations had to be established, and roundhouse and shop facilities converted. Bridges needed to be strengthened and passing tracks lengthened to accomodate the heavier and longer trains hauled by the diesels. Older fixtures such as coaling stations and water tanks were scrapped along with the engines they served. But the enormous savings of diesel power were worth the bother. As its final gesture to a departed era the L & N donated some 400 of its old engine bells to small rural churches along its lines.

Freight cars underwent a similar transformation. The 50-ton boxcars and hoppers remained dominant until the postwar era, when they began to give way to 70-ton hoppers. The latter soon became the workhorse for hauling coal and were supplemented by a 70-ton covered hopper used for such commodities as talc, alumina, and dry phosphate rock. Gondolas of the same capacity were acquired to carry steel and coal. In 1954 the L & N purchased a specially designed fleet of 250 95-ton hoppers to haul Venezuelan iron ore from Mobile to Birmingham. Three years later the company put into operation its first DF or “damage free” boxcars and its first 70-ton “airslide” hoppers designed especially to carry such bulk cargoes as flour and sugar. Other specialized cars, such as automobile and other types of flatcars, also made their appearances. Sometimes the L & N improvised to meet some specialized need. On one occasion, for example, it simply converted some 500 older freight cars of several types into flatcars with bulkheads to accomodate a growing traffic in pulpwood.

The L & N’s commitment to modernizing and upgrading its rolling stock was an impressive one, but it fell short. Despite every effort there were not enough cars. An annoying and elusive equipment gap continued to be one of the company’s most pressing problems. The lack of adequate investment capital accounted in part for this dilemma along with the twin devils of inflation and depreciation. The rising cost of replacing worn-out cars got no assistance from existing tax regulations on depreciation. As management complained in 1958:

Accrued depreciation on the old cars retired is based on the original cost when built many years ago, and provides for recovery of original cost only.

This basis is wholly inadequate under present conditions, because the original cost thus recovered is but one-third to one-half of current replacement cost.

Therefore, merely to maintain transportation capacity at the existing level, the large difference between old and new freight car prices must be supplied by reinvestment of a portion of the Company’s earnings … together with borrowing that must be repaid from future earnings.12

To handle this new equipment efficiently the L & N also made substantial investments to expand and improve yard facilities. Most of the company’s yards received some attention, often to accomodate them for particular needs. About $146,500 was spent relocating the tracks at the Choctaw yards near Mobile in 1953 to handle growing imports of Venezuelan iron ore. Modernization proceeded across the board, however, and three brand-new yards were constructed: Radnor yard (Nashville), Hills Park, later named Tilford (Atlanta), and Boyles yard (Birmingham). Actually Boyles had served as the Birmingham yard since 1904 but had become so inadequate to current needs that virtually a new yard was built around the old facilities, which formed a part of the new receiving yards.

The cost of these three yards alone exceeded $34,000,000, but the L & N considered it money well spent. All three handled classification by gravity and featured car retarders; at Boyles and Tilford both retarding and classification were done electronically. Each yard utilized automated equipment, radio, radar, and television wherever feasible. Tilford received a new freight house adjacent to the yard which was shared by the L & N and Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis. The two systems shared the entire Radnor complex, which had 100 miles of track and could handle 3,0 cars a day. Boyles could accommodate 3,500 cars daily in normal operation and 4,200 cars in peak conditions. It was also designed to handle the Atlantic Coast Line’s freight traffic as well. In March, 1959, the company broke ground for a new yard and terminal complex, the Wauhatchie yard, near Chattanooga.

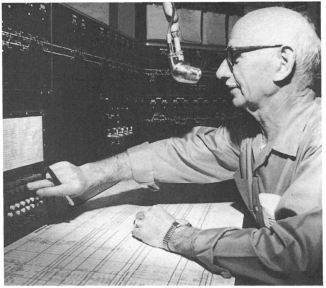

On the road itself Centralized Train Control was installed at a quickening pace. One of the great virtues of CTC, as the L & N soon realized, was that it could serve in effect as a second track without the high cost of construction and maintenance. On one 67-mile stretch of the Cumberland Valley division, between Corbin and Loyall, Kentucky, the L & N took up the second track once CTC was installed. By 1959 the company had 1,250 miles of main line covered by CTC and work was proceeding on the mileage between Mobile and New Orleans. The Nashville had another 522 miles of road covered by CTC as well.

An operator at the signal and switch controls of a modern CTC installation.

This growing network represented only one of the more spectacular forms of mechanization being utilized by the L & N. The drive to achieve the economics of efficiency meant not only new and better equipment but also increasing use of machines to replace costly and less efficient men. To that end the L & N eagerly sought out every improvement it could find. Teletype facilities were introduced in the 1950s to speed communications, and two-way radios were put into freight trains for end-to-end transmission. Specialized tools and machines were acquired to expedite the work of the renewal and track surfacing gangs. By 1958 every division had one of these specially mechanized gangs.

All along the line bridges were strengthened and modernized and lighter rail replaced with 132-pound rail. In 1958 the L & N began laying its first continuous welded rail sections, an innovation that cut maintenance expenses. Trackside electronic “hot-box” detectors were installed to help spot overheated journals before a derailment occurred. Mechanization extended into the general offices as well where accounting, bookkeeping, and payroll procedures were delivered over to new generations of sophisticated machines. In 1955 the L & N instituted centralized hiring of employees in Louisville and later extended it to four branch offices. One welcome intrusion of technology came in the summer of 1955 when the company air-conditioned its general office building.

The tactics of modernization went beyond technology to techniques as well. New methods and ideas were no less vital than machines in keeping the company afloat. On this score the L & N owned a mixed record. It turned readily to certain new techniques, especially when they furthered the grand strategy of diversifying the company’s business. In this respect it inaugurated the Trailer On Train Express (TOTE), later known as “piggyback,” in August, 1955. Adopting the adage that if you can’t beat them, join them, the company offered to carry loaded trailer trucks on specially designed flatcars between stations for a charge equal to the trucker’s tariff for the same run. So successful did it become that in July, 1959, the L & N joined several other railroads in purchasing a separate corporation, Trailer Train Company, which was established to own and maintain a pool of flatcars for the carriers to use in piggyback service.

In the passenger realm the L & N resorted to any and every device to reverse the decline. A substantial portion of available capital went to new passenger cars. New terminals, built jointly by the L & N and several other roads, opened in New Orleans and Mobile. Symbolically enough, the $41,000,000 New Orleans facility, completed in 1954, required the L & N to abandon its main line tracks along Elysian Fields Avenue. The loss of any Elysian fields in passenger revenues was painfully evident in a tactic the L & N reluctantly extended during the postwar period: a sharp reduction in passenger trains and passenger service on mixed trains. Between 1950 and 1959 no less than seventy-four of the former and thirty-four of the latter were eliminated for an estimated aggregate saving of $5,700,000 a year.

By this tactic management indicated not a wholesale retreat from all passenger business but a concentration on the stronger major runs. Two new “name” trains, the Humming Bird running between Cincinnati and New Orleans and the Georgian operating between St. Louis and Atlanta, had been inaugurated in 1946. These became the focal point of L & N passenger service, and got first priority on new equipment. To condition the younger generation to rail travel, the L & N launched an annual running of “Kiddie Special” trains. Begun modestly in 1948 and extended in 1951, these outings took grammar school children on a 60-mile round trip between Louisville and Lebanon Junction. By 1959 the “specials” had carried nearly 75,000 youngsters on such journeys. Special trains were also run for groups of financiers, industrialists, civic leaders, and other interest groups. Perhaps the ultimate public relations gimmick came in 1954 when the company shot a 25-minute color film entitled “The Old Reliable” depicting the system and the territory served by it.

Beyond the gimmickry lay some ambitious efforts to lure new industries to L & N territory. A rapidly spreading phenomena, the industrial park, proved vital in this quest. To attract groups of new plants into regions adjacent to its lines, the L & N bought land and offered to sell it to interested firms at reasonable prices. The company then undertook to assure these sites of adequate water and utilities, and constructed spur lines to the plants when necessary. During the 1950s industrial parks burgeoned at Louisville (where the L & N built a 5.2-mile spur largely to service the General Electric plant there), Birmingham, Frankfort, Eden-wold, Tennessee, and Jackson, Tennessee.

Once new industries located in the South, the problem became one of persuading them to use rail transportation instead of other forms. In this difficult assignment the L & N achieved only limited success. Part of the problem lay in the diversity of needs among the new industrial and manufacturing concerns. The proliferation of specialized car and schedule requirements compounded the L & N’s capital shortage dilemma. It also aggravated the problem of empty car mileage. In an earlier, simpler era, when most freight was hauled by general purpose cars, rolling stock could carry like or similar commodities in both directions. But as cars became more specialized, it grew increasingly difficult to fill them on return trips. By the 1950s the L & N found it almost impossible to get more than 50 per cent loaded mileage, to say nothing of idleness caused by leisurely loading or unloading and seasonal fluctuations of use. In short, the investment in equipment was rising and the maximum return from usage was falling.

But that was only part of the problem. Another crucial aspect concerned marketing techniques, and here the L & N adapted slowly to changing conditions. Traditionally marketing for railroads, especially prior to 1920, “consisted primarily of soliciting tonnage from customers away from other railroads and, later, from other modes of transportation. Confronted by potent competitive pressures, the L & N in the postwar era slowly grasped the notion that marketing had to extend beyond mere solicitation to a vigorious sales effort that stressed the advantages of services offered by the company. Perhaps the conservative tradition of the company helped retard its progress toward this realization, but after 1945 the need for new marketing techniques was urgently underscored by the competitive situation and the growing complexity of industrial production. It would be a long road to reform, however, and the full effects would not be felt until the 1960s.

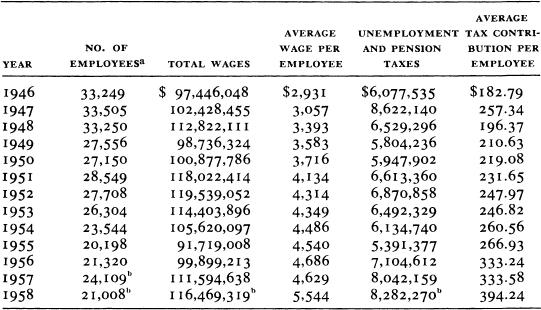

Of all the pitfalls awaiting the L & N after 1945, none proved more baffling or insoluble than the labor question. Seemingly simple in structure, it resisted every attempt at solution by frontal assault and betrayed practical difficulties of labyrinthian complexity. The basic situation can be outlined easily. Since 1940 the unions had grown progressively more powerful. Wracked like everyone else by the inflationary trend of the economy, they pressed wage and benefits demands upon the railroads with mounting vigor. Conflict eventually led to compromise settlements, which inflicted two kinds of spiraling costs upon the railroads: the expense of higher wages and similar benefit programs.

To these soaring labor costs were added the burden of obsolete work rules that both increased company expenses and impaired efficiency of operations. Since labor costs comprised the largest financial outlay for railroads, management logically adopted the policy of substituting machines for men wherever possible. Despite their high initial costs, machines had the indisputable virtues of being efficient and never demanding higher wages or extended benefits. Moreover, they were oblivious to work rules. Sensing the specter of enforced obsolescence by automation, labor clung all the more desperately and tenaciously to the old rules and the bargaining leverage of their unions. Quite naturally they had no desire to sacrifice themselves to the engines of progress.

The situation was equally desperate for both sides. Neither intended deliberate malevolence toward the other. Management had no desire to drive its employees to the wall; on the contrary it ardently sought harmony, good will, and mutual understanding. Labor did not wish to destroy the companies upon which its livelihood depended. It was ready to embrace reconciliation if only terms agreeable to both could be arranged. It was not personal or institutional malignance that spawned their perpetual conflicts; rather it was the furious momentum of those compelling forces that defined the postwar economic environment. In the crucible wrought by those forces the needs of both sides proved to be decisively and profoundly incompatible. All the good will and public relations in the world could not alter the brutal fact that both sides were fighting for their lives, and the road to survival bred conflict rather than conciliation.

The basic structure of this clash was evident in the negotiations of June, 1941. The rail unions demanded substantial raises in pay rates and certain other benefits, to which the railroads responded with proposals for changing the overly rigid work classification rules that had developed out of World War I and since become fossilized. Bargaining was done at the national level by both labor and management. With fine precision they advanced through every step in the ritual prescribed by the Railway Labor Act except arbitration, which the unions rejected. When no settlement was reached, the unions threatened to strike and thereby prompted President Roosevelt to appoint an emergency board on September 10.

After due investigation the board published its findings on November 5 only to have the unions reject them. To prevent a strike Roosevelt reconvened the board and persuaded both sides to accept it as a mediating body. After further hearings a compromise agreement was reached. Basically it gave operating employees a raise of nine and a half cents an hour and non-operating employees a boost of ten cents an hour. A minimum wage of forty-six cents an hour was established, varying paid vacations were granted, and similar raises were given to those employees not represented by the union negotiators. Consideration of the proposed work rule changes was deferred for eighteen months. To achieve this settlement Roosevelt had in effect bypassed the Railway Labor Act by offering a better solution from the White House. The precedent was an ominous one, for in future years labor leaders would continually threaten to go to the White House if a board decision displeased them.

In broad terms this ritual became the basic scenario for railway labor negotiations for the next three decades. Each one varied in its terms, specific issues, and range of emotional dynamics, but the plot remained about the same. Goaded by inflationary pressures, the unions inevitably won some degree of wage hikes. More important, they shrewdly traded some of their demands to keep any major changes in work rules buried in limbo. Try as they might, the carriers could not shake loose from these restrictions which they considered no less suffocating than governmental regulation. At the same time railway payments for unemployment and retirement taxes mounted steadily as the rates increased and the provisions were broadened.

Over every negotiation the unions wielded the Damoclean sword of the strike, which left management-labor relations ever poised on the razor’s edge. Since the railroads could find no way to halt advancing labor costs, they sought desperately to reduce the working force by mechanization. The result was a seeming paradox wherein the payroll rose steadily while the number of employees declined. This uneasy situation undercut much of the L & N’s continuing effort to improve employee relationships. The program of special meetings with the “family” at selected points along the line, inaugurated by Hill, remained in effect after the war. In 1947 it was augmented by a comprehensive training program for all officers and employees designed to inspire “a more active interest in the efficient and courteous performance of duty and to improve relations with the public.”13

Aimed specifically at personnel who had contact with the public, the program was an amalgam of better public relations, improved service, and a fostering of internal good will. The company drew upon the College of Education facilities at the University of Kentucky and University of Alabama for expertise in devising and evaluating the course training. Salesmanship was a prime subject, especially for personnel in the traffic department. In addition a general course entitled “Living Better” was introduced at thirty points along the line. Staffed by members of the operating department who had taken special training at the University of Alabama, the 18-hour course attempted to meet “the urgent need for employees in industry to have a better understanding of the functioning of the American Economic System.”14 The principles of free enterprise, not the least of which was the necessity for management and labor to work together in harmony for their mutual interest, were further espoused through the “family meetings,” the press, and civic organizations. One notable company meeting, replete with entertainment, drew 15,0 employees with families and friends to Louisville on June 7, 1950, to celebrate the company’s Tooth anniversary. For this special occasion the L & N published 200,000 copies of a 24-page illustrated brochure describing the L & N’s history, 175,000 copies of a billfold calendar, playing cards with the centennial insignia, and several other forms of printed matter including newspaper advertisements.

Management lauded the effects of its Friendly Service meetings and related public relations work, but it did not rely upon them alone. Contacts were extended into civic, industrial, and educational organizations. The press was especially cultivated. Speakers and promotional literature travelled a wide circuit. Committees were formed on every operating division to:

acquire by personal contacts a better understanding of community interests, ambitions, and problems. Often there are matters in which L & N personnel may be of assistance. With a closer understanding and knowledge of the community, L & N personnel can at the same time be of greater service in civic and community matters and also can aid in a greater understanding of some of the railroad’s problems on the part of the public.15

This community orientation was recognized as an effective tool for bettering the company’s external relationships, and as such it was good business. But it also helped advance internal relationships by promoting “family” solidarity and fostering a vision of mutual interest and progress. To further that aim the L & N expanded its activities program. Such groups as the Cooperative Club, the Veterans Club, and the athletic clubs continued to flourish. The Golf Club received a new home in Coral Ridge, Kentucky, equipped with clubhouse, nine-hole golf course, and swimming pool. A fishing club was established in 1955 at LaGrange, Kentucky, and bowling and golf tournaments sponsored by the company president became annual affairs. In 1956 the L & N offered to pay tuition for supervisory personnel taking selected courses in adult education at any college or university.

The attempt to preserve and promulgate the “family” vision simply did not reflect the realities of relationships within a large corporation, and it could not possibly affect bread-and-butter issues which were fought at a national level and therefore transcended individual workers and even corporations. The clashes over these issues mounted steadily in intensity between 1941 and 1959. When negotiations broke down in 1943, Roosevelt took possession of the railroads on December 27 to forestall a strike that might injure the war effort. The carriers continued to operate under their own managements, however, and after a settlement was finally reached the government relinquished control on January 18, 1944.

During 1944 the five operating unions drew up a long series of rule changes which were negotiated with the carriers during the early months of 1945. No agreement was reached, and on July 24, 1945, the unions served formal demands for the rule changes and for wage increases amounting to $2.50 a day. The non-operating unions followed with a demand for raises of thirty cents an hour. The ensuing conferences produced no results and the National Mediation Board was enlisted in December. All the unions except the trainmen and engineers agreed to arbitration; the latter groups announced a strike vote, prompting President Truman to appoint an emergency board to consider their requests.

On April 3, 1946, the arbitration boards granted a 16-cent-an-hour increase for the other unions, but the latter organizations rejected this figure as inadequate and demanded another fourteen cents an hour. Two weeks later the emergency board recommended the same 16-cent increase for engineers and trainmen and met a similar rebuff. With all five operating unions unhappy, the engineers and firemen called a strike for May 18. The president intervened personally but got no results. Accordingly, on May 17 he took over the railroads and put them under control of the Office of Defense Transportation.

A 5-day strike truce was negotiated, but a series of tense conferences proved fruitless. On May 23 the two unions struck and paralyzed the nation’s railroads. The next evening Truman delivered a radio address appealing for a return to work. He announced his intention of appearing before a joint session of Congress on May 25, at which he asked specifically for legislation allowing him to draft the engineers and trainmen into the armed forces. He also outlined a program designed to prevent the recurrence of such a crisis. Even before he spoke, however, the recalcitrant unions came to terms. The terms granted a total increase of eighteen and a half cents an hour, which eventually was extended to all the unions, and declared a moratorium on work rule changes for one year. Truman’s request for legislation was then ignored and the railroads were surrendered by the government on May 26. But the basic cleavages remained, and the growing legacy of bitterness received fresh fuel. A strike that same spring by the United Mine Workers further crippled the coal-dependent L & N.

During the next few years this familiar scenario continued to unfold. In 1947 both operating and non-operating unions gained raises of fifteen and a half cents. The dispute over work rules continued. Once again mediation failed, the engineers and firemen rejected arbitration, and an emergency board was appointed. The board made its report on March 27, 1948, but the unions rejected its findings and renewed their strike threat. In April the non-operating unions, joined by the yardmasters, compounded the problem by demanding a 40-hour week with no reduction in wages, overtime pay for weekends and holiday work, and a 25-cent wage increase. When they too declined arbitration, the president created another emergency board to study their controversy.

Meanwhile a strike by the operating unions loomed on the horizon. Once again, on May 10, 1948, the president seized the railroads and retained control until July 9. The final settlement allotted the operating unions fifteen and a half cents along with some rule changes in their favor. Eventually the non-operating organizations got their 40-hour week and a 7-cent-ρer-hour increase. The 40-hour-week provision with no pay reduction in effect amounted to a wage increase of about 23½ cents an hour. Other demands of less importance by several unions were handled through the normal machinery of the Railway Labor Act. However, by 1949 it was manifest that the Act was an inadequate piece of legislation to mediate the escalating strife between management and labor.

This dismal pattern continued unabated into the 1950s. When a renewed controversy over wages and a 40-hour week with 48-hours’ pay for conductors, trainmen, and yardmen erupted in 1950, the government took possession of the railroads again on August 27 and did not return them until May 23, 1952. In the furious welter of negotiations, no union remained dormant for very long. By 1952 wage agreements were beginning to incorporate automatic cost-of-living adjustments which, ironically, led to slight decreases in pay early in 1953. By that time the focus of bargaining was shifting toward the area of fringe benefits such as paid vacations and holidays, medical and life insurance, and free transportation on the employer road and other lines. An emergency board opened hearings on the differences in January, 1954. In little over a year these issues, which seemed only to be following what was by now a familiar plot, exploded into the most savage and violent labor dispute in L & N history.

For nearly fifteen years the L & N management had watched expenditures for wage and benefit increases spiral upward. Apparently helpless to deflect this trend, management could only pare down the rate of climb wherever possible and make gloomy observations that “as economies in operation are effected, the savings are absorbed by increases in wage rates and vacation, welfare and pension fringe benefits.”16 In 1954 the company elected to make some effort to stem the tide. An emergency board report had recommended that the railroads grant to non-operating unions two new fringe benefits: seven paid holidays and three weeks’ paid vacation (instead of two) for employees with fifteen years’ continuous service, and compulsory hospital, medical, and surgery insurance under a national plan at a cost of $6.80 per month, which was to be divided equally between carrier and employee. All the railroads signed agreements accepting these provisions except the L & N and its affiliates.

The company’s management conceded the vacation and holiday benefits but refused the compulsory insurance. It raised strenuous objections to any plan that compelled mandatory deductions from employees. In place of the national plan the L & N offered a voluntary plan which it claimed provided equal benefits at a cost of only $1.85 a month to employees instead of the $3.40 required by the national plan. This was possible because southern industries could obtain cheaper health insurance policies since hospital costs were lower in that region than elsewhere.

Defending both principle and cheaper costs, the L & N stuck adamantly to its own voluntary plan. The voluntary arrangement may indeed have been the preferable one from a logical viewpoint, but the unions would have none of it. On March 9 the ten non-operating unions, representing over 70 per cent of the L & N’s work force, announced they would strike the L & N, the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis, and the Clinch-field on Monday, March 14.17 Although Tilford later claimed the L & N received no official notice of the strike or the reasons for it, the company filed suit that same day to enjoin the workers from striking. The stage was set for a dramatic showdown.

On March 14 the unions went out as scheduled. Tilford announced confidently that the company had enough supervisory personnel to man key non-operating positions, but his position was eroded when some operating crews agreed to honor the picket lines. The L & N promptly sought and obtained a temporary injunction in Kentucky to order operating personnel to cross the picket lines. The order produced confusion and mixed results. Some of the six operating unions refused to cross the lines, yet 1,235 of the 1,384 employees in the general office building reported for work as did about 50 per cent of the South Louisville shop employees and 40 per cent of the mechanical employees. The engineers declared their intention to work, but the firemen hung back.

Grudgingly the L & N curtailed its passenger schedules. The operating unions promptly filed suit to dissolve the temporary order while the L & N, denouncing the strike as illegal, sued two unions for $645,000 damages plus another $215,000 for each day the strike continued. At once the slowdown hit the Harlan County coal mines, where lack of cars shut down twenty-eight mines and idled 14,000 miners. By March 17 the L & N was forced to suspend passenger operations entirely. Governor Lawrence Wetherby proclaimed an emergency and pleaded with President Eisenhower to intervene personally and reconvene the emergency board. Unlike his Democratic predecessors, however, Eisenhower declined. He left matters in the hands of the National Mediation Board, refused to appoint an emergency board, and remained aloof from personal contacts with either side. That left only Wetherby to hold the fort, scurrying among his fellow governors in the affected states in search of a solution.

The L & N professed willingness to put the matter before an emergency board but George E. Leighty, chairman of the negotiating committee for the unions, rebuffed the suggestion as a waste of time and money. Shortly afterward the union announced that they rejected the recommendations of the recent emergency board and considered all the issues present in May, 1953, reopened. Specifically they now pressed for the L & N’s acceptance of the national medical plan with the railroad bearing the entire cost of $6.80. This would, the unions noted wryly, satisfy the company’s objection to compulsory contributions by employees. Management blanched at this news. By Tilford’s estimate the board’s original findings would cost the L & N about $2,000,000 a year; the May, 1953, demands would amount to approximately $10,000,000 a year.

Everything depended on the operating unions, and there the L & N blundered. Late in March the company sent out letters warning members of those unions who were honoring the picket lines to return to work or lose their jobs. A howl of protest went up. The engineers, who were not formally honoring the picket lines, threatened to strike if layoffs were made. Hastily, management back-pedaled on its stand but did not retract it entirely. The National Mediation Board held constant conferences, jointly and separately, with both sides in Washington but got nowhere. The board’s chairman, Francis A. O’Neill, Jr., observed wearily, “In my eight years on the board this is the most stubborn case I’ve seen.”18

The deadlock deepened. In a Louisville speech Leighty proclaimed to his cheering supporters that there would be no settlement without the railroads paying the full cost of medical insurance. Exhorting the faithful to brace themselves for a long ordeal, a spokesman for the maintenance-of-way men cried out, “Before we will submit and return to work without an honorable agreement, we’ll let the L & N grow up in ragweed higher than our heads. God bless you, we’re at war, and we’re going to win that war.”19

Amidst this martial rhetoric the conflict worsened and escalated toward violence. On April 1 a section of L & N track eleven miles southeast of Lebanon Junction was dynamited. That same day communication lines in the Birmingham yards were cut and a home and café owned by two non-striking employees were damaged by explosions. These blasts injured no one, but the next day a nine-month-old baby suffered a brain concussion when an explosion ripped the front porch of a non-striking switchman in Nashville. During the next few days incident piled upon incident. A small bridge on the L & N main line was blown up; a non-striking electrician reported harassing telephone calls and found his car smeared with white paint with “scab” lettered on it; employees in the South Louisville shops had the tires on their cars slashed; a Birmingham car inspector found a stick of dynamite with a fizzled fuse on his porch; and another bridge just south of Kenton County, Kentucky, was set on fire.

As these events multiplied, state, county, and local police along with the FBI opened investigations but met little success. The unions strenuously denied that their men were responsible. One union representative stated flatly that “We don’t condone anything of that nature. It’s against the policy of the Union. Everybody has been cautioned against any violence.”20 Complaining that it lacked adequate police protection, the L & N resorted to the courts for injunctive relief. On one occasion management sought to limit the number of pickets to two at each entrance to the general office building after working employees leaving for lunch were surrounded by pickets and subjected to epithets, catcalls, and a verse “Scabby, Scabby Rats” sung to the tune of “Davy Crockett.”21 Several employees in different locations reported being attacked and beaten, and near Louisville a bullet fired through the cab of a locomotive wounded one man slightly.

For the L & N the main problem was to keep some semblance of service going. Having cancelled all passenger trains, the company concentrated upon freight. Permits were issued for cargoes on a priority basis. Supervisory personnel and shopmen familiar with diesels were drafted and trained in train operation and transportation rules. Other supervisory employees from the engineering and maintenance-of-way departments were spread along the line to operate signals, draw bridges, and man repair squads. Even so, the L & N failed to get traffic movement above 25 per cent of normal operations.

By April 15 the situation deteriorated sharply. The firemen struck the L & N and were soon followed by the trainmen and enginemen. These operating unions gave two related reasons for their decision: they had to protect the seniority of their members and they were protesting the dismissal of members who refused to report for work. The engineers did not go out formally, though all the operating unions respected the picket lines. The new strike complicated the overall situation and crippled the company’s attempt to keep traffic moving. That same night, April 15, the Nashville’s only operating passenger train, the Dixie Flyer, was derailed near Nashville. None of the crew or sixteen passengers were injured seriously, but the company promptly labelled the accident as deliberate sabotage. The FBI moved in to investigate. Later the ICC investigation confirmed the railroad’s allegation.

On April 17 both sides agreed to the National Mediation Board’s recommendation for arbitration but differed widely over the details. Leighty expressed the union’s doubts succinctly when he declared that the “unions felt they could not trust the railroad to carry out an arbitrator’s recommendations.”22 Nevertheless the non-operating unions agreed to submit all unresolved issues to a neutral referee whose decision would be binding on both parties. When the L & N balked, the unions took out an advertisement in The New York Times twitting management for its obstinance and insisting that “only the L & N and its allied roads have refused to settle this dispute.”23

Management naturally took a different view. It believed that the unions planned to win a war of sheer attrition. Tilford put the matter bluntly in his later report:

It was evident from the beginning the unions were not ready to settle and were sparring for time. They wanted to wear down the railroads and force settlement on their own terms. When the railroads continued to operate (although under limitations), burning, dynamiting and other forms of sabotage were used to interrupt operations.24

This strategy was made possible, management noted bitterly, by the fact that the strikers received unemployment pay from a fund administered by the Railroad Retirement Board (see Chapter 19). Most of the non-operating men got $8.50 per day, approximately 75 per cent of then-average pay. This money was tax-free and had been contributed to the retirement board by the railroads themselves. Operating union men also obtained the same amount even though they were “unemployed” only because they refused to cross any picket lines.

The savage irony of this situation stung management to the quick. In acid tones Tilford summarized the dilemma facing his side:

… They [non-operating unions] could take turns upsetting every proposition offered. Why should they worry, their members on strike were getting nearly as much “rocking chair” money as when working and without income tax or payroll tax deductions. And all the while the operating employees, who would not cross the picket lines but who had no grievances against the company, were winning the strike for them.25

Firm in its convictions, management ran its own ad in the Times proclaiming its willingness to settle but declining to surrender “the principle that it has no right to become a party to any contract or agreement that forces any employee, against his will, to pay any part of his wages for something he does not want.”26 In language that surely drew applause from the shade of Milton Smith, the company issued its manifesto:

•that wages of an employee belong to him.

•that the fruits of a man’s labor are his property and that no man, no employer, no organization, other than government itself, has any right to command his property without his consent.

•that this principle is embedded in the Declaration of Independence and in the Constitution … and is a priceless heritage of free Americans.

•that it is treasured by our employees as it is by all other freedom-loving citizens.

WE SHALL DO EVERYTHING WITHIN OUR POWER TO DEFEND THESE SACRED HUMAN RIGHTS.

Still the White House remained aloof, and organized efforts by Governors Wetherby of Kentucky and Clement of Tennessee to end the strike failed. Public opinion, especially among affected industries and businesses, mounted steadily but found no effective way to exert pressure. Meanwhile the incidents of violence spread. A fracas at Evansville caused the company to shut down operation there entirely. Clashes between pickets and non-strikers became commonplace at numerous points. On April 23 four engines and twenty-seven cars of a 95-car coal train were derailed south of Barbourville when the train hit an open switch and plowed into a string of empty coal cars parked on a siding. Six crewmen were injured. More bridges were fired and signal installations dynamited. A total of twenty-one bridges were damaged, six of which were completely destroyed. Tilford later estimated total property damage at $851,000 on the L & N alone. Traffic interchange with connecting lines grew progressively more difficult, and two smaller roads ceased to interchange with the L & N altogether.

The pressures for a settlement intensified. The operating unions grew restive because their unemployment pay represented only about half their regular wages. By late April both sides were ready to accept arbitration, but the details of agreement proved difficult to arrange. A final act of violence in Tennessee briefly delayed proceedings when a striking employee was shot to death by a non-striker who claimed self-defense. This first strike-related death led the union representative to walk out of the negotiations. Conferences resumed quickly, however, and on May 9, fifty-seven days after the strike began, the adversaries signed an arbitration pact. Thus ended one of the longest railroad strikes in American railroad history. The pact stipulated a return to work on May 11 and the commencement of binding arbitration the next day.

Freight service commenced on May 11 and passenger runs on May 16. Francis J. Robertson, a Washington lawyer, was named arbitrator. The L & N agreed not to file any civil suits against the unions or individual employees for violence or sabotage, but possible criminal charges were left in the hands of law enforcement agencies. Seniority remained unaffected. Having no grievances to arbitrate, the operating unions dropped out of the dispute altogether. On May 19 Robertson presented his decision. It gave management little to cheer about. Robertson ruled that the L & N must foot the entire cost of the disputed medical insurance. He gave three reasons: an improvement in the earnings outlook; a national trend toward employer-supported plans; and the L & N’s opposition to compulsory employee contributions.

In this fashion the L & N preserved its principle but financially was hoisted by its own petard. Tilford drew some meaningful lessons from the experience. First, he denounced the use of retirement funds to support strikers as legally and morally unacceptable. He also questioned the latitude given union officials in utilizing strike votes. In this instance the strike vote had been taken eighteen months before the call-out, during which time much had happened. “In such circumstances,” he concluded, “a new strike vote should be taken under the direction of neutral persons before a strike can be called.”27 Thirdly, he deplored the failure of law-enforcement officials to protect company property from sabotage and violence. Finally, he condemned the inadequacy of the Railway Labor Act to handle such a crisis. It had protected neither the disputants nor the inconvenienced public, and the ultimate force of public opinion had failed miserably. “The experience in the L & N strike indicates that the time has come to give administrative procedure in labor disputes the force of law, subject to judicial review. … Settlement by the law of the jungle can no longer be tolerated in labor disputes of transportation agencies and utilities serving important and indispensable public interests.”28

The L & N board formally extended Tilford its congratulations and vote of confidence on his handling of the strike. Under a 3-year national agreement, labor relations remained stable and tranquil through 1959. But the strike of 1955 cast a long shadow over the thinking of management and labor alike. If nothing else it demonstrated the extent to which their interests and needs had tracked onto a collision course. Well into the foreseeable future the family would remain a house divided. By 1959 both sides were bracing themselves for the next showdown. By then management had resorted to the innovation of taking out insurance to cover payment “of a sum equal to certain limited and unavoidable expenses which continue to accrue despite any work stoppage.”29

During the postwar years the L & N continued the process of pruning its administrative structure and reorganizing it where necessary to fit new conditions. While the basic organs of management, the board, the executive committee, and the two finance committees, remained intact, the company underwent several revisions of its by-laws. In 1950 the board created a new committee known as the Advisory Committee, to be composed of the chairman of the board, chairman of the executive committee, and a third member selected from the board. The new committee was given a vague definition of function and thereby became a handy and flexible adjunct to the board. Hill became the third member upon retiring from the presidency in 1950.

Structurally the L & N tried to reorganize its holdings for maximum efficiency and usefulness. Older subsidiaries that had outlived their usefulness were discarded. The old Gulf Transit Company, for example, which had done no business since 1930, remained on the company’s books until 1954, when the L & N finally dissolved it. The physical system also underwent some changes. Slightly more than sixty miles of track, including the Elkton & Guthrie and Bloomfield branches, were abandoned during the early 1950s. At the same time a modest but productive amount of new mileage was built. Two branches in eastern Kentucky, the 10-mile Leather-wood Creek (Perry County) completed in January, 1945, and the 10-mile Clover Fork (Harlan County) completed in May, 1947, opened up about 12,200 acres of coal land and provided access to another 47,800 acres. These branches were built “in anticipation of loss of traffic due to depletion of coal mines.”30 By the same logic the L & N constructed about forty-eight miles of spur line in eastern and western Kentucky. Another thirteen miles was built to accomodate new industries, including the 5.2-mile General Electric spur completed in 1952.

By far the most important addition to the system involved not construction but merger. In 1957 the L & N finally absorbed the 1,043-mile Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis after having controlled that company for seventy-seven years. The merger had long been anticipated and made good sense, but it took the goad of the troublesome postwar economic environment to bring about the formal integration. Upon inaugurating the action in 1954 management observed that “better control of mounting operating costs would be achieved and the single organization could meet more effectively competition from other modes of transportation, especially those using highways, waterways, and airways.”31

As usual the road to merger was far from smooth. Two centers of opposition rose to challenge it. One involved about 5 per cent of the Nashville’s stockholders who questioned only the proposed stock exchange ratio of one and a half L & N shares for one share of Nashville. The second source of dissent came from the city of Nashville, which disputed the merger itself. Both challenges led to lengthy litigation that resulted in decisions favorable to the L & N. The absorption of the Nashville on August 30, 1957, made the L & N the third largest railroad in the South and sixteenth largest in the nation. By 1959 the company operated 5,697 miles of track.

In one other area, that of officer compensation, the L & N adopted some new practices in the 1950s. Since most officers remained outside the pale of collective bargaining agreements, they lacked any fixed process for determining their salary and raises in pay. The company remedied this in 1957 by authorizing the president and executive committee to establish a policy on the method of compensation for persons with salaries of $12,000 a year or more. Every new appointment in that category was to be reported to the board.