William H. Kendall, president of the L & N from April 1, 1959, to April 1, 1972.

The history of the L & N since 1959 can only be summarized here. Such recent events fall logically to the charge of that historian who takes up the company’s second century of operations. Recent events lack sufficient perspective to evaluate them clearly, and some of the sources are not yet available for inspection and analysis. Moreover, the pace of change in the modern world is such that any effort, however earnest, to place the past decade in some accurate context is doomed to failure. It is not only the L & N but the railroad industry itself that straddles the threshold of a new era. Under these circumstances the historian becomes little more than a thinly disguised soothsayer. What follows, then, is simply an attempt to describe the major developments since 1959.

Insofar as a general pattern emerges from these busy years, it is one of past policies pursued at an ever accelerating pace. Confronted by the demands of a new economic environment after World War II, the L & N responded with a broad strategy based primarily upon the pursuit of modernization. In struggling to improve its deteriorating competitive position and combat a long-term inflationary trend, the company undertook a determined campaign to cut costs, improve its physical plant, and provide broader and more efficient services for its customers.

The basic tactics for this campaign were forged and honed in the decade or so after 1945. They served the company well and proved successful in maintaining the L & N’s position as one of the nation’s strongest carriers. That same strategy proved a reliable guide after 1959 as management, taking advantage of favorable economic conditions and a veritable explosion in technological innovation, extended the scope of modernization with unhesitating vigor. In a single decade the L & N transformed the procedures of operations more profoundly than all the developments since 1900 had. Yet, when the smoke cleared, the company still found itself locked in a feverish and seemingly endless quest for security. In a world rampant with change, success remained as elusive as ever.

It was perhaps only fitting that the L & N should acquire a new president at the beginning of its second century of operations. On April 1, 1959 Tilford retired as chief executive and was replaced by William H. Kendall. A native of Somerville, Massachusetts, Kendall graduated from Dartmouth and its Thayer School of Engineering in 1933. Despite the inauspicious times, he obtained a job in the maintenance-of-way department of the Pennsylvania Railroad. He rose to division engineer with the Pennsylvania before leaving to accept a position with the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad in Wilmington.

The Coast Line connection proved to be a permanent one. In January, 1949, Kendall became assistant to the general manager, and shortly thereafter was made assistant to the president. That assignment was brief, for in October, 1950, he was named general manager of the Clinchfield. His first appointment with the L & N came in December, 1954, when he was made assistant to the president. Three years later he became vice president and general manager of the L & N, and in October, 1957, was elected to the board.

A stocky, soft-spoken man with a gift for stripping problems to their essentials and making hard decisions, Kendall has upheld the enviable L & N tradition of vigorous executive leadership. Upon taking office he was perhaps better acquainted with the inner workings of the system than any president since Mapother, an invaluable asset in an era of rapid change that allowed little time for remedial homework. His lines of authority were clarified and strengthened in April, 1961, when Wiggins stepped down as chairman of the Atlantic Coast Line and L & N boards. The office of chairman was abolished, leaving the president as sole chief executive, and the board ceased to meet at 71 Broadway in New York, where it had been convening since 1902. This administrative change was symbolic of the new age in which the L & N found itself, one that was rapidly severing its ties with the past.

William H. Kendall, president of the L & N from April 1, 1959, to April 1, 1972.

As president Kendall followed the basic strategy of modernization shaped by Hill and Tilford. He pushed the program for expanding and updating the L & N’s equipment; he sought to introduce new techniques and methods in every area; he replaced men with machines wherever possible and pushed the company into progressively more sophisticated computerization; he modernized plant, operational, and office procedures; he made some key additions to the system; and he continued the fight against restrictive governmental regulation, the labor dilemma, and subsidized competitors. He upheld the “Four Freedoms” advanced by the Association of American Railroads as a:

Magna Carta for Transportation …

Freedom from discriminatory legislation

Freedom from discriminatory taxation

Freedom from subsidized competition

Freedom to provide a diversified transportation service1

Late in 1959 Kendall echoed his predecessors in diagnosing the company’s dilemma:

The most important problem of the L. & N. is still that of reducing costs so we can stay competitive. Everything we’re doing is aimed at effecting economies and getting business back. It’s difficult to say whether we’ll gain on the problem or just hold our own… .2

What Kendall did in pursuit of this objective did not differ significantly from the policies of Hill and Tilford except in scope. During his administration the modernization program proceeded at a pace and on a scale that dwarfed previous efforts. The generally favorable economic conditions of the 1960s helped make this possible, but management’s fierce commitment to the strategy played a major role as well. Whether or not that strategy would ultimately prove successful can only be determined by some future historian. The remainder of this epilogue attempts to outline the recent contours of the modernization program. Some of its dimensions are illuminated or extended by direct quotations from William Kendall, which are given in italics.

As always, top priority in capital expenditures went to rolling stock and plant equipment. Between 1960 and 1968 the L & N spent roughly $407,000,000 on new equipment and another $99,000,000 on improvements to roadway property. The result of this outlay was to reduce the age of L & N rolling stock steadily. In 1960 the average age of the company’s freight train equipment was 13.08 years. That figure declined to 10.67 years by 1964 and dropped to 8.16 years by 1969, giving the L & N one of the youngest car fleets in the industry. Evidence that the trend would continue was provided in 1969 when the L & N launched the largest equipment-acquisition program in its history: the addition of sixty locomotives and 7,014 cars in little over a year at a cost of about $100,000,000.

Motive power showed a different trend, advancing from an average age of 10.22 years in 1960 to 14.10 years in 1969. In part, however, this reflected the newness of the diesel fleet itself and the durability of the locomotives. During that same period the size of the fleet increased from 733 to 834, and the later models were heavier, more powerful, and capable of hauling larger loads on less fuel. The L & N’s first replacement diesels, obtained in 1962, had 2,250 h.p. and were 50 per cent more powerful than the units they replaced. By 1966 the company was adding to its roster 6-axle diesels with horsepower ranging up to 3,000. An operational innovation occurred in 1964 when the L & N became the first railroad to use electronically regulated diesel units, unmanned and automatically controlled, in the middle of a freight train.

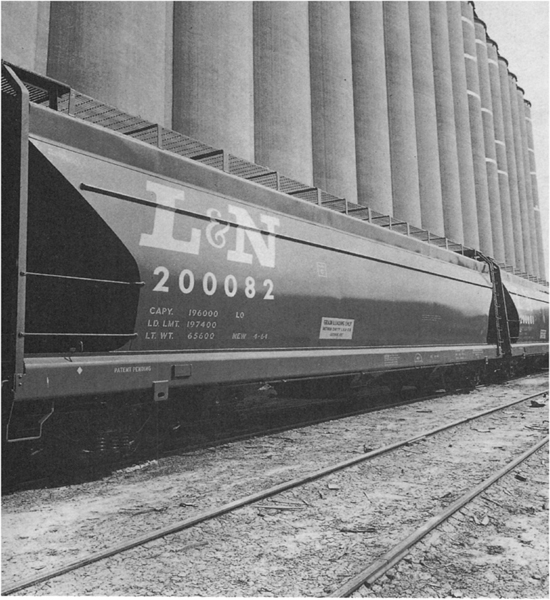

Freight cars continued to undergo transformation in size and function. New models included several varieties with 80- and 100-ton capacities. A 100-ton coal hopper capable of being unloaded automatically in half a minute was developed, as were open and covered hoppers of the same size. The L & N was one of the nation’s first railroads to employ the big covered hoppers, which featured long trough hatches on top for continuous bulk loading. Known as the “Boca Grandes” and “Big Blues,” these hoppers carried such commodities as grain, cement, and silica sand. The L & N also pioneered in the use of 60-foot, 100-ton boxcars for hauling iron, paper, steel, and automotive products as well as manufactured goods. Another innovation, the jumbo boxcar, 86.5 feet in length with a cushioned underframe and a capacity of 10,000 cubic feet, was used for carrying automotive stampings.

OPPOSITE: No. 3007, an EMD GP-40 diesel acquired in 1967 from Electro- Motive, typical of the “second-generation” high horsepower diesels which began to replace the older models in 1962.

“Big Blue” the 100-ton covered hopper with a capacity of 4,650 cubic feet.

The development of freight cars reflected the increasingly diverse and specialized needs of shippers. The jumbo boxcars became an integrated segment of automotive assembly lines and were shuttled between northern parts plants and southern assembling plants. Three types of bulkhead flatcars, with 70-, 90-, and 100-ton capacities, performed a variety of functions. One type was adapted to carry cast-iron pipe and fittings, which were palletized for shipping and loaded and unloaded by fork lifts. One giant 12-axle, 300-ton flat was acquired to transport oversized loads, and the L & N purchased a handful of 11 o-ton depressed center flats for moving packaged boilers. Some jumbo open hoppers were designed for carrying woodchips, and gondolas were converted into coke carriers. This willingness to adapt and improvise made possible such prodigious feats as the hauling in 1963 of a 1,330,000-pound refinery reactor vessel belonging to Standard Oil of Kentucky.

Even relatively standardized cars took on new jobs. The L & N used 60-foot, 100-ton boxcars to haul a wide variety of cargoes, and several hundred DF (damage free) boxcars were equipped with load-retaining devices to expedite the movement of less-than-carload traffic. No less a bastion of tradition than the caboose underwent striking design changes, including new color schemes, bay windows on both sides, and numerous new facilities for comfort, convenience, and safety. In 1967 the L & N began testing a new automatic side-dumping car developed in collaboration with Pullman-Standard. What the L & N could not acquire or develop it leased, a conspicuous example being a fleet of 70-ton insulated, bunker- less refrigerator cars owned by Fruit Growers Express, of which L & N is part owner.

One of the most striking innovations concerned the emergence in 1962 of unit trains for hauling coal. The early version used 70-ton hoppers to move thirty-eight carloads every weekday from coalfields in western Kentucky 225 miles to Florence, Alabama, where it was dumped into barges for delivery to a TVA power plant. Gradually the trains were lengthened to seventy cars, hoppers were increased to 100 tons, and new runs were installed wherever customers, usually power plants, required large and regular coal supplies. Special chutes were designed to pour coal into the hoppers at the rate of thirty-five tons a minute, which enabled trains to be loaded fully in less than three hours and without coming to a complete stop. In 1963 eight unit trains handled with 3,000 cars a volume of coal that once would have required 4,000 cars. Small wonder that the L & N expanded the program to sixteen trains by 1969 and eagerly planned further growth. In that year the trains were carrying a third of the company’s coal traffic using less than 10 per cent of its available cars.

In this modernization program the company shops played an important role. They were responsible for converting a considerable amount of rolling stock for specialized purposes. One of their more spectacular feats involved some stretching surgery on boxcars in 1962. The shopmen cut 100 standard 40-foot, 50-ton boxcars in half and converted them into 50-foot, 50-ton cars with increased capacity. Another 100 cars were sliced in half and stretched, but these were also given larger doors and 70-ton trucks to shoulder heavier loads. The passenger-car shop made its contribution in the form of a new counter-lounge car designed to replace the diner by serving more customers counter-style with fewer attendants.

The purpose of every innovation was to maximize service and minimize cost. More cargo had to be hauled by fewer cars at faster speeds. Turnaround time had to be reduced sharply, and existing equipment had to be utilized as fully as possible. The L & N bent every effort to achieve these goals and made remarkable strides, but it still fell substantially short of its goals. Despite every effort the supply of rolling stock lagged behind the demands of an ever expanding traffic. The significant improvement in service failed to still the protests of impatient shippers, especially during periods of peak shipments. In 1963, for example, the L & N experienced one of its worst shortages of coal cars and drew a fusillade of complaints and even threats of litigation. The recurring problem involved several interrelated components: too few cars, poor utilization of existing cars, and a correlation between car utilization and quality control.

(Well, we need rolling stock, that’s our greatest requirement today. As the economy generally grows and the tonnage handled by the railroad increases, we’re going to need more physical facilities to handle it… . Generally speaking, we just need to do a better job in moving goods and moving them on time and being able to keep our customers informed of the location of their shipments so that they can plan their production, their distribution without experiencing delays in receipt of their goods. We have a long way to go in that respect and it’s going to take modern techniques to do it.)3

Unit coal train being loaded automatically with 5,000 tons of coal at Paradise, Kentucky.

This same pattern extended to improvements to property and maintenance as well. Innovations in rolling stock meant little if the facilities handling it were not upgraded at the same time; accordingly, the L & N intensified its efforts in this area. Large sums went for expanding and modernizing yards. The new Wauhatchie yard opened in the summer of 1961 and boasted eighteen tracks accommodating 1,444 freight cars with a maximum capacity of 2,500 cars a day. A much larger project, the enlarging of the DeCoursey yard in Cincinnati, was begun in 1960 and completed in December, 1963. For an investment of about $11,500,000 the L & N obtained a yard with eighty-nine tracks capable of holding 7,370 standard-length cars and possessing a daily capacity of 7,000 cars or nearly twice that of the old yard. An enlarged yard at Atkinson, Kentucky, completed in September, 1963, replaced three smaller yards and became an assembly point for unit trains. The Leewood yard at Memphis and the Tilford yard were also expanded.

To service its growing fleet, the L & N invested $5,000,000 in expanding the facilities of its South Louisville shops. Since all heavy maintenance work was done there, the company rearranged the basic layout, added new facilities, and installed a variety of modern equipment, some of it designed and built by the L & N itself. The new equipment, such as a machine that trued diesel wheels without removing them from the locomotive, repaid its initial investment by lowering maintenance and repair costs. At most of its major yards the L & N installed a “one-spot” car-repair facility for its rip tracks, each of which was equipped with “Link-Belt double-drum continuous car hauls with dog sleds; jib cranes with three electric hoists each; oxygen-acetylene hose reels; whiting Rip- jacks, electric traversing screw jacks; welding machine with electric cable reel, and Whiting Trackmobiles.”4

Such innovations were by no means a cure-all or final solution, for the new equipment brought new problems. The heavier and more travelled freight cars spent more time in the shops; the 100-ton hoppers, for example, tended to produce more flange wear than lighter cars, and the new diesels proved less reliable than anticipated. C. N. Wiggins, the assistant vice president-mechanical, observed that the newer high-horsepower diesel- electric “is a sophisticated unit, compared to the units that came before. And power is not performing as dependably as it should.”5 To cope with these new problems the L & N intensified programs in three areas: shop- craft training (including apprentice training), increased and improved preventative maintenance, and a revision of repair-shop facilities. On the last point Wiggins noted that it was time to “look at a second generation of repair facilities. We want our industrial engineers to take a look, to see if we can improve on what we have.”6

On the line itself the L & N instituted several new practices. The roadway was improved by expanded use of 132-pound welded rail and better ballasting techniques. In 1964 the company introduced its Rail Test Car No. 1, a mobile unit equipped with electronic devices for detecting imperfections in rail joints where most rail defects occur. Six years later a second test car, built at a cost of $100,000, was acquired. The new model featured more sophisticated hardware and relied upon ultrasonic waves rather than magnetism to uncover flaws. On a more prosaic level, the L & N increased its maintenance-of-way expenditures and devised new procedures for its work gangs. The trend was toward increasing mechanization and faster replacement of worn facilities, a task made all the more urgent by the toll taken on the roadbed by heavier, longer trains.

New DeCoursey yard, completed in 1963.

An automatic tie inserter at work.

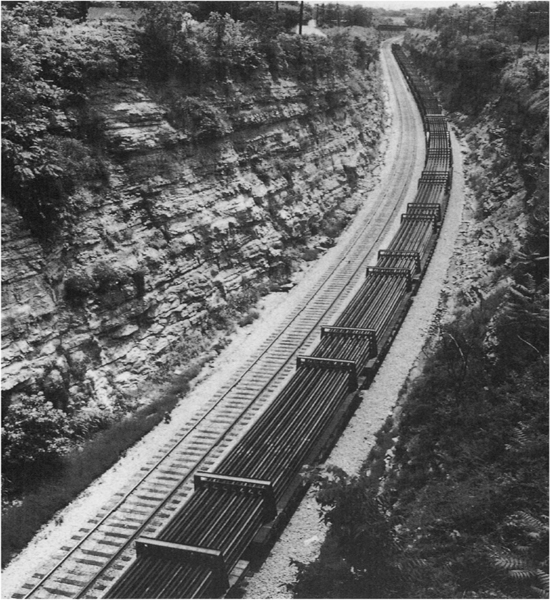

A welded rail train en route to the field laying site..

The use of CTC was extended steadily during these years. By 1963 the entire main line between Cincinnati and New Orleans was under CTC control. Four years later CTC operated over 1,976 miles of the system, with more to come. Here, as elsewhere, success depended upon utilizing the most modern equipment, and that meant not only alert management but continuing access to capital. (I would say that the major problem today is economic, the matter of obtaining capital… . We’ve not been too successful in the past in attracting capital to this industry. We need to have a better basis for earnings; we’re not earning enough on our fixed assets to make it attractive for private capital to invest in railroad securities. We’ve not had a great deal of difficulty in recent years in borrowing money through bond issues and equipment trust certificates, which are the classic ways of railroad financing, but we do need to have a better base for borrowing and a better opportunity for earnings in order to attract investment capital… .

I think that in the last ten years, or more particularly in the years prior to that, we have gone to many, many different kinds of equipment, different applictions of techniques … and certainly from a technological standpoint we’re not lacking in progress. The principal problem again is the one I referred to in the beginning—the money to do this… .) 7

If the L & N’s massive and diversified fleet embodied the signs of change, its employment of new electronic equipment expressed a revolution. During the 1960s the company plunged into the age of computerization with a vengeance. The result was a sweeping change in the techniques of management and operations as well as new ways of thinking about all the traditional problems of running a railroad.

The electronics revolution reached into every department. Communications especially underwent a transformation. As early as 1963 the L & N possessed one of the nation’s largest independent railroad communications systems, including 3,000 miles of teletype circuits and 10,000 miles of carrier telephone circuits, to say nothing of an extensive microwave network. By 1967 the company owned some 5,000 miles of pole lines which carried 18,687 carrier voice circuits and 5,626 circuit miles of data communications. It also leased another 2,105 voice circuit miles and 687 circuit miles of data communications. This network has continued to grow steadily.

These communication systems found a plethora of uses, especially when used in conjunction with computers. Beginning in 1960 the L & N acquired a Univac computer to trace and account for all cars on the line. Two years later the Univac gave way to an IBM system which was itself supplanted by another IBM system in 1964. Within three years the company had advanced to a third generation of computers, the IBM 360 system. The new complex of machines, coupled with the sprawling communications network, enabled the L & N to revolutionize its procedures in the areas of payroll and accounting, billing and collection, customer service (especially car-location inquiries), car, locomotive, and train data transmission, and the broad category of management science.

The L & N completed its central data-processing center at Louisville in July, 1962. Within a short time the new complex was handling all payroll information, and by 1964 it had replaced 314 freight accountng stations with twenty-four regional offices. All billing and collection was thereafter centralized in Louisville. In 1961 the L & N added a new vice president—accounting and taxation—and commenced a total reorganization of accounting functions to tackle increasingly sophisticated needs and to take advantage of the new machines. Tax and electronic data-processing functions were separated from the accounting department and given to new departments with appropriate officers.

Some of the more spectacular advances came in the area of car handling and customer service. When the Louisville data-processing center opened in 1962, the L & N installed electronic processing and transmission equipment in seven major freight yards. Linked to the home records center, these machines replaced manual operations for such tasks as preparing train consists, demurrage reports, carload freight bills, car record books, switch lists, and interchange reports. In 1964 the L & N began to install the new IBM 1050/360 system and thereby took its first step toward a “real time” system capable of obtaining exact location and movement data on a given car instantly in response to a customer inquiry.

By 1967 that goal had been largely realized. During that year, the company noted proudly, it “installed a comprehensive ‘real time,’ on-line computerized information and control system. With instant information on hand concerning not only cars and their contents, but yards, trains, locomotives and other types of equipment, the system is being programmed ultimately to display instantly critical situations on television-like tubes.”8 This system covered only special purpose cars in assigned service—about 20 per cent of the L & N’s fleet—but the company was busily devising linear programs to control the general purpose cars as well.9

By the end of 1967 some seventy-five large shippers and over seventy L & N yard and traffic offices could make direct daily inquiries to the central computers through Telex and TWX terminals in their own offices. Customer service centers were opened at East St. Louis, Mobile, Memphis, and Nashville for this purpose. The new techniques were utilized extensively in yard operations as well. Here the emphasis was upon quality control and forecasting movements and humping procedures according to priorities arrived at by computer calculations. A pilot program at the Radnor yard, utilizing an IBM 1130 computer and real-time data, demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. By establishing classification priorities through forecasts of freight-tonnage accumulations far enough in advance to schedule outbound movements ahead of congestion, Radnor moved steadily toward its objective of saving three hours per car per day.

Automatic Car Identification (ACI) unit on L & N main line at South Park, Kentucky.

Basically the Radnor project worked this way. The program identified all cars in the receiving yard with a numerical value based on their destination and length of time on hand. These values and other data were fed into the 1130; the resulting printout gave a current inventory of the receiving yard every two hours based on advance consists along with the proper sequence for humping the cars on hand. This sequence was based upon a numerical value per car, with the cut having the highest per car value being first. The result, as William J. Herndon, assistant manager- equipment, noted, was that “the yard master’s printout has everything— how the yard inventory has changed, the listing of cuts on hand, the fast track, the extra track, the city track, and so on.”10

The Radnor project was in effect a computer-simulated model of yard operations designed to measure and improve the efficiency of operations. The use of simulation increased steadily to the point where the L & N contemplated the completion by spring of 1971 of a network model “with simulation capabilities surpassing those which any other U.S. road has come up with thus far.”11 The developing model’s first test produced uncomfortably precise results. Simulation of an operating change told researchers that a service improvement of 48.7 hours would result if it were put into effect. The change was made, and a month later investigation of the operation reported a service improvement of exactly 48.7 hours. Small wonder that management eagerly anticipated putting the completed model to work, though the researchers were careful to keep it reasonably simple and limit the number of major points (where cars can enter or leave the reporting system) to twenty-six.

These developments, and others not touched upon, justly established the L & N as a front-runner among American railroads in employing the new electronic gadgetry. Internal structural changes illuminated the pace of progress in this area. In 1968 the data-processing center, then only six years old, was reorganized, realigned, and renamed the Management Information Services (MIS). The reorganization created three service divisions (general disbursements and cost accounting; operation, communication, and engineering; and traffic, revenue, and car accounting) and one production division, computer operations. Broadly speaking, the three service divisions developed computerized programs for various L & N departments while the production division, which had direct responsibility over all computers and other equipment, actually ran the programs. The immediate work force of MIS, including supervisory and administrative personnel, numbered almost 200, which suggests the department’s growing importance. The machine population has not yet been calculated.

In January, 1969, the L & N went beyond the mere use of computer techniques to become a purveyor of them. It established a subsidiary corporation, Cybernetics & Systems, Inc., “which will be used by it to take advantage of its position in the field of computerization by entering the so-called ‘software’ industry. Our belief is that this subsidiary offers a meaningful investment opportunity for the L & N in a growth industry.”12 The new company offered computer counseling, programming, and comprehensive management information systems to perspective customers. Though failing to make a profit its first year, the subsidiary was cultivating a clientele for its services.

The impact of computerization obviously affected the L & N’s labor dilemma, but it by no means resolved or disposed of the problem. Machines continued to replace men, but there were clear indications that this process was reaching its outer limits. (We’ve gone into data processing in a very substantial way, and this has made great changes in the methods of doing the paperwork, let’s say, of the railroad industry. But it’s still being done by the same people but they’re doing it in a different way.)13

During the 1960s management and labor continued to skirt the brink of direct collision, but nothing resembling the disaster of 1955 occurred. In 1960 the carriers and operating unions agreed to submit work rules and practices to a presidential commission for study. The commission announced its findings in February, 1962. Basically it recommended the gradual elimination of firemen in both freight and yard service, revision of wage bases to place more emphasis upon time consumed than upon miles run, and some lesser changes. Since the major provisions pleased the carriers by striking at two of the most flagrant “featherbedding” practices, the railroads accepted the recommendations.

Predictably the unions rejected them and, after the usual round of negotiations and mediation, declined arbitration as well. When the carriers proclaimed their intention of putting the orders into effect, both sides took refuge in the courts. The case drifted upward to the Supreme Court which, on March 4, 1963, decided 8–0 in favor of the railroads. Still the unions balked, and negotiations over both primary and secondary work rules issues broke down. Congress resorted to a joint resolution providing for compulsory arbitration to break the deadlock. On November 26, 1963, the arbitration board, with slight modification, sustained the carriers’ position on firemen in its Award No. 282. The decision also set guidelines for determination of the crew consist issue.

Immediately the unions attacked both the award and the law behind it in the courts. The case marched steadily toward the Supreme Court, which in April, 1964, refused to review a lower court decision upholding the award. In May the L & N began eliminating firemen and by the year’s end was operating 70 per cent of all assignments without them. Crew sizes in branch and yard service were also reduced. Here, as with the firemen, the process was ameliorated by the inducement of voluntary early retirements. But the union continued to demand the restoration of firemen and even asked for an apprenticeship program for firemen. Their efforts were to no avail. To that extent the ancient work rules were modified, but they had by no means been modernized to meet current conditions.

Aside from the traditional jousting over wages and fringe benefits, no other serious labor disputes marred the decade. The number of L & N employees declined steadily from 19,318 in 1960 to 14,940 in 1968. The figure rose to 15,669 in 1969 only because the L & N acquired part of the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad. The essential dilemmas of the 1950s remained pressing and unresolved in 1970, as did the fundamental cross-purposes of management and labor. And no promising solutions loomed on the horizon.

(For many years we’ve sort of been leveled off in many areas of productivity. We’ve mechanized to the greatest extent possible in some of our procedures, but we’ve not changed our operating regulations at all in recent years. We’re still operating trains today with crews that are paid on a basis of running a hundred miles. When those rules were put into effect back in the early part of the century, a hundred miles constituted nearly a day’s work. Today it’s substantially less than a day’s work, and until we can really get a day’s productivity from the people that are operating the trains and pay for that day, I think we are going to have difficulty in making economic progress.

We look to the future as an opportunity to sit down with the organizations that represent our people and work out new rules and regulations under which they can work comfortably and prosperously and so can we. Together, why I believe that the two can find a way or find a solution to the railroad industry continuing to operate efficiently and economically in the transportation field.)14

(Our principal commodity for many years has been coal, and it still maintains a very important part of our revenue picture. About 40 per cent of our originated tonnage is coal, and that reduces to about 25 per cent of our gross freight revenue. Looking down the road, we see at least five years of continuation of the growth in coal. This is primarily, of course, for the electric generating industry.)15

Though the amount of coal carried by the L & N increased steadily, its proportion of total L & N traffic continued to decline. This fact reflected two trends: a growing demand for coal and a widening diversification of business obtained by the company. The importance of coal was reasserted in 1970, when earnings in virtually every other area followed the downward trend of the economy. By contrast coal jumped from 40,572,400 to 48,146,273 tons, and carloadings from 578,837 to 666,861. The commodity actually reversed its downward proportional trend by accounting for about 45 per cent of total tonnage. In 1970 about 53 per cent of this coal went to electric utilities, 17 per cent for other industrial uses, another 17 per cent for coking, and the remaining 13 per cent for export.

For the moment coal remained king, but challengers were emerging everywhere. During the 1960s new industries streamed into the South at a rate well above the national average. Between 1960 and 1967, some 1,726 firms located along the L & N’s lines. Together they represented an investment of approximately $1,800,000,000. In addition, existing industries spent more than $1,200,000,000 expanding their facilities. The newcomers represented an incredible diversity of industries ranging from a second large Ford Motor Company plant to chemicals, paper products, rubber, processed foods, steel, marble, metalware, and a host of others.

By providing specialized equipment and other assistance, the L & N developed important new sources of business where none has existed before. The most spectacular example of this was in piggyback and automobile traffic. Inaugurated in 1955, piggyback (formerly TOTE) took advantage of new equipment and facilities to achieve tremendous growth. The first major breakthrough came in the summer of 1960, when the L & N put its first bi-level rack cars in service to carry automobiles. So popular did the service become that in October, 1961, the company scheduled its first all-automobile piggyback train, running from Nashville to Atlanta. Two years later it offered piggyback service for less-than-carload freight, “with door-to-door pick up and delivery at point of origin and destination provided by contract carriers.”16

The results were impressive. Trailerloads increased 362 per cent from 1959 to 1960. Automobile movements grew from less than $1,000,000 in 1960 to $3,500,000 in 1961, while other piggyback operations jumped from $750,000 to more than $2,000,000. Automobiles reached 15,553 trailerloads in 1962 and other piggyback traffic 16,553 trailerloads. During the next five years the combined trailerloads tripled, going from 32,700 in 1963 to 96,700 in 1967. Total revenue produced soared from $9,500,000 to $25,800,000 in that same period. Since 1967 the upward trend has continued at a less gaudy pace. For most piggyback work the L & N utilized 89-foot flatcars with cushioned underframes and hitches. The multi-level automobile transports used 85- to 89-foot flats with two or three racks. In the fall of 1963 the company commenced running two fast freight trains, known as “auto vans,” which travelled from Cincinnati to Jacksonville in about twenty-seven hours. The trains carried only automobiles and piggyback trailers southward and returned with more piggyback traffic and perishables. As of 1970 the piggyback system included sixty-eight permanent and fifteen portable ramp-points with a leased trailer fleet of 2,700 vans.

To encourage new industries and solicit business the L & N resorted to new techniques. The policy of abetting the development of industrial parks was pursued vigorously. For this and other work the L & N had created a department of industrial development under the administrative wing of the vice president-traffic. In 1961, for example, the Louisville Chamber of Commerce helped form a corporation to promote the development of an industrial park. Anxious to secure the business such a park would produce, the L & N’s director of industrial development surveyed the region adjacent to company lines and recommended a 200-acre tract west of the Strawberry yards. The board was urged to purchase it because “if this property is acquired by the Company there is a likelihood the site will be adopted as the location of said industrial park … but that in any event the President feels that the 200-acre tract should be acquired by the Company because of its industrial potential.”17

A multi-level auto transport unit at the Radnor yard, Nashville.

This sort of planning became commonplace. By 1963 the L & N found it desirable to incorporate a subsidiary company with broad powers to undertake “urban and industrial development and redevelopment, the leasing of personal and real property, equipment purchasing and rebuilding, equipment leasing… .”18 The subsidiary would be able to undertake certain functions not allowed the parent company in its charter. From this thinking emerged the Houston-McCord Realty Company, which specialized in acquiring acreage for industrial development. The subsidiary’s work required considerable capital, which had to come from the L & N. Nevertheless management deemed it money well spent. As Kendall observed to the board contemplating a transaction in 1967, “It is essential to the growth of this Company that there be available along its lines suitable sites for industrial development; that if Houston-McCord acquires the properties under option the prospects are good that a substantial portion … can be sold on satisfactory terms to industries which will generate substantial freight traffic for movement over the lines of the Company.”19

To procure business the L & N modernized its marketing techniques and launched the most sophisticated and aggressive sales campaigns in its history. As always the emphasis was on service, but the performance tools were refined. By the early 1960s the company’s salesmen were working out of fifty-one regional offices. Backed by the constant flow of computerized data, the sales force was trained to solve shipping problems for their customers and obtain business through a persuasive blend of expertise, concern, and service. Salesmen were prodded to become transportation experts knowledgeable not only in traffic capability but also in the related fields of economics, rates, regulatory law, and government. “We’re devoted to making every man able to sell total transportation or distribution—we want every salesman to know everything about his customers,” observed Douglas McKellar, vice president-sales. “We find shippers to be very receptive to our men when they ask to study the shipper’s distribution problems, including the movement of commodities moving non-rail.”20

The field work was buttressed by an advertising campaign in various media stressing a “we can solve your problem” approach. Customer Service Centers were opened in Nashville, Memphis, Mobile, and St. Louis to provide a central source for information on rates, car tracing, car supply, and other data. As new service functions developed and administrative units proliferated, the problem of effective integration threatened to become a major obstacle. Accordingly, the L & N took an important stride toward centralization by opening on February 1, 1970, its System Service Center. Headquartered in Louisville, the new office unified several previously disparate functions to achieve four basic objectives: establish and maintain good customer service; furnish real-time solutions to any operating problems that could not be solved at the local level; provide an adequate supply of equipment to meet whatever demands arose; and achieve maximum utilization and profit from all freight equipment.

“The General,” 4–4–0 American type rebuilt and reactivated by the L & N in April, 1962. As part of the Civil War Centennial activities that year, “The General” visited twelve states, travelled 9,000 miles under its own power, was inspected or ridden by nearly 700,000 people, and took part in a re-creation of Andrews’s Raid at Kennesaw, Georgia.

In one area the L & N’s ambitions were restrained by long-standing legislation. The competitive pressure upon railroads, as well as increasing complexity of their traffic, logically pointed to the carriers diversifying not only their business but their modes of transport. It seemed natural for railroads to follow the lead of other industries and redefine their function—to become transportation corporations instead of merely rail carriers. The low return on rail investment further supported this notion.

Unfortunately, the ICC saw otherwise. (About the only diversification that has occurred in this country today has taken place under the “grandfather clause” of the Motor Carriers Act back in 1935. Some railroads were permitted to continue operating highway transportation over routes that were in existence at that time).27 Since then numerous carriers tried unsuccessfully to gain the privilege of establishing highway transportation; others failed in their attempt to set up complementary water service. Some railroads had actually participated in air service before the regulatory authorities forced them to quit the field in the early 1930s. That left the carriers with nowhere to go. They could arrange coordinating operations with other forms of transportation, and the L & N created an extensive network of bulk-distribution terminals where such commodities as chemicals were unloaded directly into trucks and distributed further to those customers needing smaller quantities. But beyond that the company could not go.

Early in 1961 management made a major effort to change this situation. The company supported a movement to obtain federal legislation permitting diversification. Meanwhile, to prepare itself for possible success, the board authorized and the stockholders ratified an amendment to the charter giving the company broad powers “to acquire, own, lease, operate, maintain, pledge and dispose of any and all motor vehicles, aircraft, water craft and any other equipment or property of whatsoever kind necessary… .”22 The new amendment waited in vain, however, for the federal legislation has never materialized. Unlike virtually every other industry the railroads remain prisoners of their originally defined function. They can diversify into other businesses but not into other forms of transportation.

Does the L & N still want to diversify? (We definitely would. We think it’s in the public interest that transportation of commodities be performed by the most economical method to suit the needs of the customer. Whether it be the cost in money or time, certainly no one mode of transportation can do everything. And we believe that under one management shipments can be handled via different modes of transportation, interchanging at strategic points perhaps; but nevertheless the customer should be offered the variety of services that would best suit his needs and one transportation company could do that… .)23

One conspicuous area resisted the general upward performance trend on the L & N. Passenger traffic continued to shrivel at a disheartening rate. In 1960 passenger revenues totalled $8,440,949. With inexorable consistency they slid downward to a paltry $1,717,476 in 1969. Passenger cars owned by the L & N dropped from 530 to 204 during the same period. More trains were discontinued, schedules were cut, and smaller stations closed or refitted for other duties.

Still the L & N clung doggedly to the vestiges of its service. Improvements were made on several cars, the most important being disk brakes and newer air-conditioning units. Two new diner-lounge cars were added to the fleet in January, 1960, and that same June a new $500,000 passenger station was dedicated at Birmingham. But it was all in vain. Travellers continued to flee the railroad in droves, and on a carrier like the L & N, which served a large territory with widely spaced population centers and no commuter traffic, extinction was only a matter of time.

(I think the day of passenger operation by the individual railroad is ended. We’ve seen this steady downward progress of patronage of our passenger trains, and we’re just about at the end of it. We only have three trains operating on the L & N today. They’re scheduled to be discontinued by the middle of next year… . Long-distance passenger travel, certainly in the next decade, is in my opinion gone. It will not be restored.)24

The L & N’s absorption of the Nashville in 1957 presaged a period of modest growth by the company. During the 1960s the L & N acquired portions of two roads, the Chicago & Eastern Illinois and the Tennessee Central, and began the process of absorbing a third, the Monon.

As early as 1961 the L & N tried to buy or at least acquire trackage rights over the Chicago’s line between Evansville and Chicago. This acquisition would give the L & N a secure line into Chicago and open up an important new territory as well as a vital terminus. For various reasons matters hung fire until February, 1967, when the ICC authorized the Missouri Pacific to acquire control of the Chicago but required it to sell the 287-mile Chicago-Evansville line to the L & N. The Monon promptly objected that such an acquisition by the L & N would hurt the former’s business between Louisville and Chicago. After further negotiations the L & N submitted on March 21, 1968, two applications to the ICC: one to acquire the Chicago-Evansville line and the other to merge the Monon into the L & N.

The C & E I purchase was approved by the ICC in October, 1968, and completed in June, 1969. The L & N acquired the line from Evansville to Woodland Junction, Illinois, outright; shared ownership with the Chicago of the line from Woodland Junction to Dolton Junction; and acquired half interest in the Chicago & Western Indiana and the Belt Railway of Chicago terminal switching lines at Chicago. The L & N also picked up half of the Chicago’s motive power, 37.5 per cent of its freight cars, and 86 per cent of its passenger cars. In return the L & N paid $6,500,000 in cash, $18,000,000 in bonds, assumed certain of the Chicago’s obligations, and surrendered to the Chicago 368,860 shares of its stock owned by the L & N.

The Monon merger moved more slowly and remained unconsummated as of April, 1971. Though part of the road paralleled the Chicago- Evansville line, it could also be used to complement an integrated service. The 573-mile Monon consisted of two lines which formed an uneven X across the State of Indiana. The main line ran 324 miles from Louisville to Chicago, with a 60-mile branch to Michigan City and a 95-mile branch to Indianapolis. The two branches intersected the main line at Monon, which ultimately prevailed as the corporate name over the more prosaic Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville. Another 47-mile branch extended from Wallace Junction to Midland, and still another one ran seventeen miles from Orleans to French Lick. These latter branches reached important mineral deposits.

The ultimate integration of these roads into single-line service promised something of a resurgence in agricultural traffic for the L & N. Both tapped rich areas of corn and soybean production, which was being shipped into the South in rapidly increasing quantities. The two roads operating separately had been unable to provide adequate equipment and sufficiently profitable rates to capitalize on this traffic but their acquisition by the L & N, with its resources and access to the grain- and feed-hungry markets of Georgia and Alabama, boded a distinct change in that situation.

The Tennessee Central presented a different problem. That troubled road, extending from Hopkinsville, Kentucky, through Nashville to Harriman, had actually filed application with the ICC to abandon operations. When hearings in Nashville revealed that between 6,600 and 8,400 industrial jobs would be lost and several industries rendered non-competitive or isolated from markets, the courts eventually decided upon a plan that divided the Tennessee’s trackage into three segments. The Southern took one portion, the Illinois Central a second one, and the L & N purchased the 130-mile segment from Nashville to Crossville. The L & N absorbed its portion in 1969.

These acquisitions caused the L & N management considerably less anxiety than a surprisingly stiff contest over a line already controlled by the company, the strategically located Western & Atlantic Railroad. That road had been leased by the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis for nearly seventy-five years, and the current lease was due to expire in 1969. As early as November, 1964, the L & N board formally approved negotiations for renewal of the lease. Unexpectedly, however, the Southern, under its aggressive, hard-hitting president, D. W. Brosnan, showed interest in bidding against the L & N for the lease. The precise motives of the Southern remain controversial, but the effect of its action was unmistakeable. The Southern already controlled two of the three lines between Chattanooga and Atlanta; if it acquired the Western & Atlantic it would possess a monopoly of the route and could effectively shut the L & N out of that vital market.

What followed resembled nothing less than a reincarnation of the flamboyant tactical struggles fought by such colorful and romantic combatants as Victor Newcomb and “King” Cole. The bids were to be opened in Atlanta on December 12, 1966. The Southern submitted a bid calling for a flat annual rental of $995,000. The L & N countered with a two-part bid. The first part called for a fixed annual rental of $900,000; the second part proposed a fixed annual rental of $600,000 plus a percentage of the Western’s revenues which, by the L & N’s calculations, would increase the total rental to more than $1,000,000 a year over the 25-year span of the new lease.

The president of the Georgia Properties Control Commission ruled that the revenue-sharing proposal was not a legitimate bid and therefore accepted the higher Southern bid. However, the Georgia General Assembly, convening on January 16, 1967, declined to approve the commission’s actions. Operating out of his private rail car, Brosnan wined and dined and lobbied legislators and other influential officials in a vain effort to stem the tide. Instead both houses adopted a resolution returning the matter to the commission with instructions to take new bids. The commission later set the date for those bids at December 21, 1967.

Once again the campaign resumed. When the Southern continued to manifest interest, the L & N countered with a substantial advertising campaign. One pamphlet published by the company quoted Henry Clay on the virtues of competition and stressed the consequences of monopoly that would ensue if the Southern were to win the lease. It also quoted Brosnan on the necessity of competition. Meanwhile the L & N board authorized Kendall to make a new bid for the Western at whatever figure he deemed necessary to secure the lease.

The L & N’s offer was a complicated one. It proposed a base annual rental of $1,000,000 plus an amount each year “equal to the product obtained by multiplying the base annual rental by an escalation factor of 2.5 percentum times the number of calendar years that the lease has run through the end of the preceding year.”25 In addition the company agreed to pay, after the first calendar year, the necessary amount to cause the total payment for that year to equal that percentage of the L & N’s operating revenues for the year which the base annual rental constituted of the company’s 1966 operating revenues. Ironically, the Southern chose not to submit another bid, so the L & N offer went unchallenged.

During the 1960s the L & N built some new mileage, mostly coal spurs. An 11-mile spur in eastern Kentucky was completed in 1963, and in 1967 authority was sought to build a 15-mile spur in Bell and Harlan counties. Two small spurs were under construction in 1971. Other mileage was built for manufacturing firms of all kinds; in 1962, for example, the L & N completed a 9-mile spur to serve the Bowaters Paper Corporation plant at Calhoun, Tennessee. On the other side of the ledger, relatively little mileage was abandoned. The largest loss came in 1965, when the board approved abandonment of sixty-five miles of line between Jackson and Cordova, Tennessee.

(I think the trend in the future will be toward less mileage rather than more. Certainly in our part of the country we have enough railroads. … I don’t foresee any large centers of population growing up away from railroads in the future, so we think we have enough facilities for handling the production of industry from now on… . But it could well be that this prediction would fall flat on its face in 25 to 50 years from now.)26

The necessity to pay for new acquisitions, as well as its general quest for efficiency, led the L & N to devote considerable attention to its financial situation in these years. In November, 1968, the company sold $40,000,000 in collateral trust bonds to pay for the Chicago-Evansville line, to construct the 15-mile spur in Bell and Harlan counties, and to replenish its shrinking working capital. Throughout the 1960s the company picked up some cash by selling off assorted parcels of land it no longer needed.

By 1968 the L & N could label itself a billion-dollar corporation as total assets reached $1,025,764,307. At the same time funded debt stood at $428,921,406, interest payments at $19,875,453, and current liabilities at $57,243,909. Gross earnings climbed steadily during the decade toward a record high of $340,594,027 in 1969. Tonnage carried followed roughly the same pattern, reaching a record 108,215,786 in 1969. Net operating earnings, the key indicator in the minds of many L & N officials, did not behave so consistently. They peaked at $69,625,528 in 1966, fell off to $54,140,683 the next year, and climbed back to $68,703,965 by 1969.

Management’s major financial concern involved the steady drop in working capital (current assets less current liabilities), which fell from $51,097,636 in 1960 to $25,411,750 in 1964. After a period of resurgence it dropped again to $29,626,089 in 1967 and rose to $50,239,999 by 1969 only through the sale of securities and net increases in the long-term debt. (Our working capital position has been declining, as has the industry’s generally. While we’re not in a deficit position, we’re not in a real comfortable position either. The cash drain we foresee from new wage settlements will make our cash problem one of the more serious problems we’ll have to face.)21

Uncertainty loomed at the higher corporate level as well. On July 1,

1967, the parent Atlantic Coast Line merged with the Seaboard Air Line to form the new Seaboard Coast Line. Speculation immediately arose as to the future of the L & N. As early as 1960, when the merger was underway, the L & N management felt compelled to deny rumors that the company would consolidate with the Illinois Central. These stories derived from reports that the ICC would force the Atlantic Coast Line to sell its interest in the L & N if its merger with the Seaboard went through. Nothing came of the matter.

In 1970 the situation took a new turn when the Seaboard Coast Line announced on December 17 that it would seek to acquire the remaining two-thirds of L & N stock not already owned by it. The matter is still pending. Whether the Seaboard’s action was to be a prelude to absorption of the L & N by the parent company remains unclear, but at least a wisp of cloud hangs over the L & N’s future as an independent system. The Seaboard-Atlantic Coast Line merger had not changed the L & N’s fundamental relationship with the parent holding company, which had always been one of independent operation and general coordination of policies. On the possibility of absorption, however, Kendall refused to speculate. (Well, that’s an economic matter that might well take on a different significance in the future. It’d be impossible to say whether it would happen or whether it wouldn’t happen.)28

On the delicate issues of taxation, wage demands, and government regulation the L & N management mellowed but did not substantially change its traditional posture. The complaints of every administration since World War I continued unabated, but fresh tones of patience and perspective crept into the lament, as evidenced by Kendall’s remarks early in 1970:

However, we cannot look forward to the new decade without the hope that in Washington and in state capitols throughout the nation there is a new awareness of the scope of the problems our industry faces.

Impatient as we are to be released from discriminatory regulations, we know this is a long-term objective and progress can only be accomplished a step at a time… .29

Well into its second century, the L & N faced no more certain a future than it had confronted in those hard years of the 1850s. Unlike those formative years, however, the perils and pitfalls awaited the entire industry rather than individual companies within it. As it had usually been, the L & N was better prepared than most of its peers to accept whatever challenge lay ahead. But the strength of a single system no longer counted for what it once did. Where once the L & N had been a major piece in a game of reasonably comprehensible dimensions, it was now a pawn maneuvering upon a board of vast proportions and complexity, helpless to determine its ultimate fate except within a restricted perimeter.

(The railroad industry is sort of at the crossroads today. I believe the economic factors that are responsible for our situation right now are perhaps solvable and we will continue as a free enterprise transportation industry. Certainly the country needs the railroad as a means of transportation. … So looking down the road, I would see railroads here in the future. I would see railroads operated by the owners as free enterprise. I can foresee many changes in that ownership or in groups that might work together. I can see other possible changes in types of service offered by the railroads, perhaps as transportation companies rather than just railroads. But in general I would certainly predict railroads will be here for a long time to come.

The L & N is a very major part of the railroad transportation system of America today, and I think we will continue as a major part.)30