Chapter 17. Computer Troubleshooting 101

This chapter covers the following A+ 220-1001 exam objective:

• 5.1 – Given a scenario, use the best practice methodology to resolve problems.

Excellent troubleshooting ability is vital; it’s probably the most important skill for a computer technician to possess. It’s what we do—troubleshoot and repair problems! So, it makes sense that an ever-increasing number of questions about this subject are on the A+ exams. To be a good technician, and to pass the exams, you need to know how to troubleshoot hardware, software and network-related issues. The key is to do it methodically. One way to do that is to use a troubleshooting process. In this chapter we will focus on the CompTIA A+ six-step troubleshooting methodology.

5.1 – Given a scenario, use the best practice methodology to resolve problems.

ExamAlert

Objective 5.1 concentrates on the CompTIA A+ 6-step troubleshooting methodology.

It is necessary to approach computer problems from a logical standpoint, and to best do this, we use a troubleshooting process. Several different troubleshooting methodologies are out there; this book focuses on the CompTIA A+ six-step troubleshooting theory.

This six-step process included within the A+ objectives is designed to increase the computer technician’s problem-solving ability. CompTIA expects the technician to take an organized, methodical route to a solution by memorizing and implementing these steps. Incorporate this six-step process into your line of thinking as you read through this book and whenever you troubleshoot a desktop computer, mobile device, or networking issue.

Step 1. Identify the problem.

Step 2. Establish a theory of probable cause. (Question the obvious.)

Step 3. Test the theory to determine cause.

Step 4. Establish a plan of action to resolve the problem and implement the solution.

Step 5. Verify full system functionality and if applicable implement preventative measures.

Step 6. Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

ExamAlert

Before you do anything, always consider organizational and corporate policies, procedures, and impacts before implementing any changes.

Let’s talk about each of these six steps in a little more depth.

Step 1: Identify the Problem

In this first step, you already know that there is a problem; now you have to identify exactly what it is. This means gathering information. You do this in several ways:

• Question the user. Ask the person who reported the problem detailed questions about the issue. You want to find out about symptoms, un-usual behavior, or anything that the user might have done of late that could have inadvertently or directly caused the problem. Of course, do this without accusing the user. If the user cannot properly explain a computer’s problem, ask simple questions to further identify the issue.

• Identify any changes made to the computer. Look at the computer. See if any new hardware has been installed or plugged in. Look around for anything that might seem out of place. Listen to the computer—even smell it! For example, a hard drive might make a peculiar noise, or a power supply might smell like something is burning. Use all your senses to help identify what the problem is. Define if any new software has been installed or if any system settings have been changed. In some cases, you might need to inspect the environment around the computer. Perhaps something has changed outside the computer that is related to the problem.

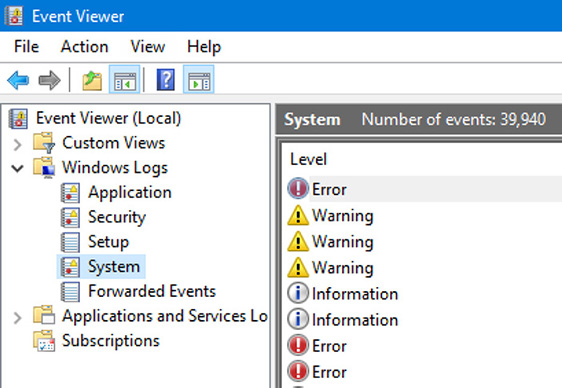

• Review log files. Review any and all log files that you have access to that can tell you more information about the problem. For example, in Windows use the Event Viewer to analyze the System and Application logs, and perhaps the Security log. Figure 17.1 shows an example of the System log within the Event Viewer.

Figure 17.1 The Event Viewer - System Log in Windows.

• Inquire as to any environmental or infrastructural changes. Perhaps there was a change on the computer network, or a new authentication scheme is in place. Maybe the environment has changed in some way: higher temperatures, more or less humidity, or a user now works in a dustier/dirtier location. Perhaps there has been recent changes to the HVAC system or the electrical system. Changes such as these will often affect more than one computer, so be ready to extend your troubleshooting across multiple systems.

• Review documentation. Your company might have electronic or written documentation that logs past problems and solutions. Perhaps the issue at hand has happened before. Or perhaps other related issues can aid you in your pursuit to find out what is wrong. Maybe another technician listed in the documentation can be of assistance if he or she has seen the problem before. Perhaps the user has documentation about a specific process or has a manual concerning the computer, individual component, software, or other device that has failed. Documentation is so important; the more technology there is, the more documentation that is created to support it. A good technician knows some details by heart, but a technician doesn’t need to know every single specification—those can be looked up. A great technician needs to understand how to locate the right documentation, how to read it, and how to update it as necessary.

Keep in mind that you’re not taking any direct action at this point to solve the problem. Instead, you are gleaning as much information as you can to help in your analysis. However, in this stage it is important to back up any critical data before you do make any changes in the following steps.

ExamAlert

Perform backups before making changes!

Step 2: Establish a Theory of Probable Cause (Question the Obvious)

In Step 2, you theorize as to what the most likely cause of the problem is. Start with the most probable or obvious cause. For example, if a computer won’t turn on, your theory of probable cause would be that the computer is not plugged in! This step differs from other troubleshooting processes in that you are not making a list of causes but instead are choosing one probable cause as a starting point. In this step, you also need to define whether it is a hardware or software-related issue.

If necessary, conduct external or internal research based on symptoms. This means that you might need to consult your organization’s documentation (or your own personal documentation), research technical websites, and make calls to various tech support lines—all depending on the severity of the situation. It also means that you might inspect the inside of a computer or the software of the computer more thoroughly than in the previous step.

The ultimate goal is to come up with a logical theory explaining the root of the problem.

Step 3: Test the Theory to Determine Cause

In Step 3, test your theory from Step 2. Back to the example, go ahead and plug in the computer. If the computer starts, you know that your theory has been confirmed. At that point move on to Step 4. But what if the computer is plugged in? Or what if you plug in the computer and it still doesn’t start? An experienced troubleshooter can often figure out the problem on the first theory but not always. If the first theory fails during testing, go back to Step 2 to establish a new theory and continue until you have a theory that tests positive. If you can’t figure out what the problem is from any of your theories, it’s time to escalate. Bring the problem to your supervisor so that additional theories can be established.

Step 4: Establish a Plan of Action to Resolve the Problem and Implement the Solution

Step 4 might at first seem a bit redundant, but delve in a little further. When a theory has been tested and works, you can establish a plan of action. In the previous scenario, it’s simple: plug in the computer. However, in other situations, the plan of action will be more complicated; you might need to repair other issues that occurred due to the first issue. In other cases, an issue might affect multiple computers, and the plan of action would include repairing all those systems. Whatever the plan of action, after it is established, have the appropriate people sign off on it (if necessary), and then immediately implement it.

Step 5: Verify Full System Functionality and, If Applicable, Implement Preventative Measures

At this point, verify whether the computer works properly. This might require a restart or two, opening applications, accessing the Internet, or actually using a hardware device, thus proving it works. As part of Step 5, you want to prevent the problem from happening again if possible. Yes, of course, you plugged in the computer and it worked. But why was the computer unplugged? The computer being unplugged (or whatever the particular issue) could be the result of a bigger problem that you would want to prevent in the future. Whatever your preventative measures, make sure they won’t affect any other systems or policies; if they do, get permission for those measures first.

ExamAlert

Make sure it works! Always remember to verify full system functionality.

Step 6: Document Findings, Actions, and Outcomes

In this last step, document what happened. Depending on the company you work for, you might have been documenting the entire time (for example, by using a trouble-ticketing system). In this step, finalize the documentation, including the issue, cause, solution, preventive measures, and any other steps taken.

Documentation is extremely important and helps in two ways. First, it provides you and the user with closure to the problem; it solidifies the problem and the solution, making you a better troubleshooter in the future. Second, if you or anyone on your team encounters a similar issue in the future, the history of the issue will be at your fingertips. Most technicians don’t remember specific solutions to problems that happened several months ago or more. Plus, having a written account of what transpired can help to protect all parties involved in case there is an investigation and/or legal proceeding.

So that’s the six-step A+ troubleshooting process. Try to incorporate this methodology into your thinking when covering the chapters in this book. In the upcoming chapters, apply it to hardware, software, and network-related issues.

Note

I also have a video on my website that discusses this six-step process:

https://dprocomputer.com/blog/?p=2941

Cram Quiz

Answer these questions. The answers follow the last question. If you cannot answer these questions correctly, consider reading this section again until you can.

1. What is the second step of the A+ troubleshooting methodology?

![]() A. Identify the problem.

A. Identify the problem.

![]() B. Establish a theory of probable cause.

B. Establish a theory of probable cause.

![]() C. Test the theory.

C. Test the theory.

![]() D. Document.

D. Document.

2. When you run out of possible theories for the cause of a problem, what should you do?

![]() A. Escalate the problem.

A. Escalate the problem.

![]() B. Document your actions so far.

B. Document your actions so far.

![]() C. Establish a plan of action.

C. Establish a plan of action.

![]() D. Question the user.

D. Question the user.

3. What should you do before making any changes to the computer? (Select the best answer.)

![]() A. Identify the problem.

A. Identify the problem.

![]() B. Establish a plan of action.

B. Establish a plan of action.

![]() C. Perform a backup.

C. Perform a backup.

![]() D. Escalate the problem.

D. Escalate the problem.

4. Which of the following is part of Step 5 in the six-step troubleshooting process?

![]() A. Identify the problem.

A. Identify the problem.

![]() B. Document findings.

B. Document findings.

![]() C. Establish a new theory.

C. Establish a new theory.

![]() D. Implement preventative measures.

D. Implement preventative measures.

5. What should you do next after testing the theory to determine cause?

![]() A. Establish a plan of action to resolve the problem.

A. Establish a plan of action to resolve the problem.

![]() B. Verify full system functionality.

B. Verify full system functionality.

![]() C. Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

C. Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

![]() D. Implement the solution.

D. Implement the solution.

6. There is a problem with the power supplied to a group of computers and you do not know how to fix the problem. What should you do first?

![]() A. Establish a theory of why you can’t figure out the problem.

A. Establish a theory of why you can’t figure out the problem.

![]() B. Contact the building supervisor or your manager.

B. Contact the building supervisor or your manager.

![]() C. Test the theory to determine cause.

C. Test the theory to determine cause.

![]() D. Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

D. Document findings, actions, and outcomes.

Cram Quiz Answers

1. B. The second step is to establish a theory of probable cause. You need to look for the obvious or most probable cause for the problem.

2. A. If you can’t figure out why a problem occurred, it’s time to get someone else involved. Escalate the problem to your supervisor.

3. C. Always perform a backup of critical data before making any changes to the computer.

4. D. Implement preventative measures as part of Step 5 to ensure that the problem will not happen again.

5. A. After testing the theory to determine cause (Step 3), you should establish a plan of action to resolve the problem (Step 4). Memorize the six-step troubleshooting process! You will use it often.

6. B. If you can’t figure out a cause to a problem and have exhausted all possible theories, escalate the problem to the appropriate persons. It happens—no one of us knows everything; and sometimes, we have to ask for help!