Inspired by the spirals and meandering lines of the natural world, this rhythmic hand embroidery is largely composed of various couched spiral forms. A variety of hand-made and commercial cords and threads were used on a silk background. Additional colour interest is obtained by contrasting the couching threads with the laid ones.

‘Once is an instance Twice may be an accident But three or more times makes a pattern.’

Diane Ackerman (American poet, essayist and naturalist, b.1948)

The widely held perception that to be called a pattern a design has to repeat exactly is simply not true. Our notion about the need for exactness of repeat is possibly born out of, and influenced by, our immediate experiences of a whole host of patterned goods, such as fabrics for furnishings and garments, knitwear, wallpaper etc., all of which have been factory-manufactured in quantity for the mass market. To satisfy demand and for economic viability, over the years the power of increasingly sophisticated machinery has been used to print, knit or weave designs in great volume. By their nature, machines from the simplest early looms to the recent digital and computerized versions for stitching, printing and weaving, are based on mathematical units that have to be planned and programmed accurately. They therefore reproduce precise designs repeatedly. But, in addition to the machine-made, the nature of some textile methods always dictate the type of pattern produced; so the regularity of the warps and wefts, even in early weaving on simple looms, the stitches in a knitting pattern, or the fabric used in counted-thread embroidery, for example, lead to precision in the patterns worked. Designs made from other materials, such as ceramic tiles in Islamic designs, also produce regular repeating patterns. Many other examples can be found too. Their methods may result in less precise patterns, but they are patterns nonetheless, as can be seen from examples later in the book.

The stimulus and starting point for most design, whether mass-produced by machine or one-off originals, is usually nature which, among its many inspirational attributes, is particularly rich in pattern. Due to our reliance on our environment for food, shelter and general survival, human beings have long needed to maintain a close relationship with nature in all its broad diversity. In earliest times man’s understanding of his surroundings, of nature’s rhythms and repetitions, the changing seasons, weather patterns, growth of plants and life cycles within the animal kingdom, have all been recorded in terms of patterns. These meaningful designs, which we can see scratched, painted and carved on cave walls, in museums on weapons, fragments of pottery and many other old artefacts, were often used in worship, rituals and magic.

For many of us, particularly those living ‘sophisticated’ urban lives, our relationship with and dependency upon nature may seem detached and remote as we have grown to expect that our need for water, food, shelter and heat can be purchased from, and provided by, various agencies and other sources. Certainly for most people, reliance on nature is perceived less directly than for our ancient ancestors, whose very existence and survival was regulated by their understanding of weather, seasonal change and by the careful use of their surroundings. It is little wonder then that earlier peoples worshipped natural phenomena, imbuing nature with magical powers to be celebrated ritualistically.

Inspiration from nature showing drawings and paintings of various natural patterns, including: 1) Buzzard feather; 2) Studies from shells; 3) Veins and colours in a coleus leaf; 4) Mosaic of dried, fragmented earth and rocks; 5) Peacock butterfly; 6) Details of microscopic patterns from another species of butterfly.

Cell Patterns by Wendy Cooke. A second piece (see also here) from a group of works based on cell patterns. Machine embroidered on soluble film, the units were dipped into fine paper pulp before hand-stitched assembly. The unit edges of covered fine wire allow for manipulation, creating an undulating surface.

Through science, we have accrued more knowledge about all aspects of our Earth. Nevertheless, we continue to be intrigued by and to marvel at the many visual wonders of nature that have inspired artists and designers since the earliest times.

In nature we find all the elements needed for interesting design: differences in line, shape and rhythm, and contrasts of scale, density, colour and tone. Also the natural world demonstrates great variety, vitality and energy that can continually inform and inspire us in our work.

‘The human brain is hardwired for pattern recognition.’

Kit White (American artist, b.1951)

In nature, pattern is characteristically rhythmic rather than necessarily repeating exactly. A good description could be ‘the same but different’. Although natural pattern is often interpreted solely as a series of surface shapes and colours, it should be noted that sometimes pattern in nature is related directly to the structure of an object. The linear and cellular features that give form and strength also, usually, create interesting designs. Depending on its function, natural pattern varies hugely from the very subtle to extremely bold and vivid. It can be matched to habitat and used by animals as camouflage. In plants pattern and colour can be used to attract pollinating insects, whilst it is also used by animals, insects and fish to intimidate and exhibit warning signals to predators. Conversely, pattern and colour are sometimes used for conspicuous display purposes in order, for example, to attract a mate.

Natural patterns, reflective of the divergence in nature, are generally categorized into detailed family groups. For clarity and expediency, these can be divided into the groups given in this chapter.

I find it helpful to think of natural patterns as belonging to one of the following groups: meandering forms; explosive patterns; branching forms; packing and cracking patterns; angular shapes; breaking and separating patterns; cloud forms; mazes and labyrinths; concentric and circular patterns; and dune and rippling patterns. These are explained briefly here, with examples of each form, and I shall end this chapter with a look at fractals, which are particularly fascinating patterns comprised of forms repeated at progressively smaller or larger scales.

Rhythmic, meandering pattern based on an aerial view of a river and its tributaries. Couched variegated cotton threads, split stitch and seeding worked on commercially dyed cotton.

These irregular natural forms are found in diverse places, their scale varying from very large to microscopic. They occur in sections of the brain, in certain animal markings and in some fossils for example. Familiar meandering patterns can be seen in maps showing winding mountain pathways and rivers. Some patterns in the group depend on their origin: perhaps movements of air and water can be transitory as rivers may change direction very slowly over time; while others may be considered more permanent as any changes occur very slowly over time. Meandering patterns are generally gentle and rhythmic.

Winding patterns found in brain tissue. Couched cords worked on a hand-dyed cotton background.

Lines that radiate in all directions from a central point in a direct path, form explosive patterns. As the name suggests, these patterns are particularly dynamic, suggest strong movement and can cover quite a large area. Examples are splashes of water, petals radiating from the centre of a flower and groups of spikes on cacti. The most energetic explosive patterns contain lines that follow direct routes out from the centre, as shown here. When the route is curved, as on petals, the effect is softer and more relaxed.

Explosive design of overlapping fine canes and flat, pointed wooden sticks. These were positioned on sticky soluble fabric, and then randomly woven together at the centre with cotton threads. Once the soluble fabric had dissolved, the work was mounted on a circle of fabric to support the centre, and more bundles of wrapped sticks were added.

Overlapping spiky motifs in satin and stem stitch worked in silks on a mono-printed silk background.

These are widespread in nature because their form provides an efficient way to distribute water, nutrients or oxygen to complex forms; a tree is a good example of branching pattern. Not only do the branches grow out of the main trunk, but they divide into smaller branches and twigs, which diminish in size the further they reach out from the centre. Similar outward-branching patterns may be seen in leaf veins, plant root systems beneath the ground and, in the human body, in blood vessels and the central nervous system. An example of an inward branching pattern is a river where springs, streams and tributaries gradually join together to form the main river body.

A hand-stitched interpretation of magnified drawings of the branching vein patterns on a drying coleus leaf. Embellishing was used to build up the mottled, brightly coloured surface from dyed cotton scrims, silk rovings and chiffon layered on low-loft wadding. Stem and split stitches delineate the branching forms, while random blocks of straight stitches and seeding are used to create the dappled background.

Stylized tree stitched on a silk background with cords and cotton threads. Couching was used for the trunk and main branches, with fly and straight stitches for the twigs.

Packing and squeezing produce a kind of natural geometry that can be seen in the arrangement of sweet corn as it grows on the cob, in bubbles pressed together in a container, in rock forms and in small pebbles that have settled together in a small space.

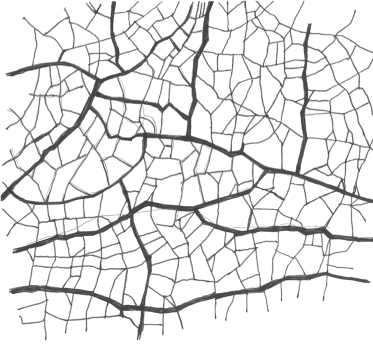

Cracking occurs in nature when elements come under stress and force, such as cooling rock, drying and shrinking mud, or in a tree’s growth when the uneven molecules making up the bark cannot expand consistently resulting in a pattern of deep cracks. In ceramics, crackle or crazing patterns occur when there is a difference in the shrinkage of the pot’s body and the glaze.

Small padded balls made from cotton-covered wadding were firmly joined invisibly to squeeze them together. Paint and seed stitch highlight each element so that the darker, negative cracks between form the pattern.

A small frame was used to create tension on criss-crossing fine Japanese paper threads. A knot was tied as each thread crossed another. Several layers of these meshes were combined to form this cracking design. The type of thread, even though fine, and the tension created make for a delicate, crisp mesh.

Pieces of blue, turquoise and black silk were trapped between a white cotton background and two layers of crisp white organdie. Sharply angled lines of straight and satin machine stitching in dark turquoise and white thread were stitched across the work before areas of the organdie (sometimes one layer, sometimes two) were cut back to reveal the silk below. White seeding and lines were hand-stitched onto the surface.

Although there is usually some order in these patterns, they are characterized in appearance by a confusion of overlapping geometric shapes criss-crossed with lines, creating sharp angles. Angled patterns can be found in cracked ice, shattered glass and in some crystalline geological elements as they disintegrate under extreme conditions such as frost and rain.

Triangles of varying sizes were cut from silks and chiffon then overlapped to form a solid background. Numerous lines of hand-stitching (couching and Romanian couching) were worked in silk and cotton threads, emphasizing the sharp angles of the design, and then some shapes were filled with crossing straight stitches. Stronger lines were made from thin natural sticks, which were also couched in place.

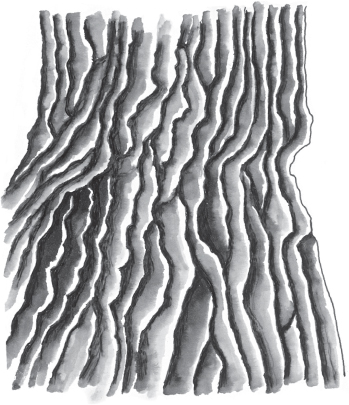

Often rich in colour, these patterns give the impression of movement frozen in time. Associated with marble and similar veined and decorative stones, the patterns have been formed through the application of extreme geological heat and pressure on the Earth’s crust, causing minerals to recrystallize and merge. Fossils and other organic debris that have been trapped in the rock are broken down by the process and turned into small calcite crystals.

A lacy surface based on scraps of black, terracotta and pink cotton was made from machine embroidery on soluble fabric. When completed and dry it was cut and torn apart, making uneven ‘broken’ fragments that were then arranged on a second piece of soluble fabric and rejoined with hand-stitched wrapped threads and straight stitches. Care was taken to join the elements securely while retaining the diagonal flow of the design and irregular spaces between.

Brown wrapping paper was partially painted with melted paraffin wax, and then crumpled to form creases. After mounting it on sticky soluble fabric, the paper was stitched in strata-like horizontal and vertical lines of straight and satin machine stitching. After dissolving the soluble fabric, and in the process allowing the paper to disintegrate slightly, it was further creased and manipulated to form the breaking patterns. Note that when working with zigzag or satin stitch on soluble fabric, a line of straight machine stitching must be worked first to stabilize the elasticity of the zigzag stitch above it.

The many different and amorphous patterns seen in the sky are full of movement as clouds billow and change according to the atmospheric conditions and the forces that affect them. Nevertheless, certain cloud forms occur often enough to be recognizable and to be given names (mackerel sky, for example). Cloud patterns range from calm and gentle to vigorously dynamic, and although always moving (sometimes quite swiftly), the repeating rhythms are recognizable. These forms can also be considered as waves, and are similar to the rippling patterns shown on pages here.

Billowing stormy clouds are interpreted in vigorous curves that are hand-stitched in couching, running stitch, stem stitch and chain stitch. Fine cotton and silk threads were used on a background painted with fabric dyes.

Rhythmic lines seen near the horizon inspired this piece. On a printed cotton background, lines of couched threads of different weights and stem stitches are offset and softened with fine vertical straight stitches. Hand-stitching in cotton threads.

Pattern created with two layers of silk. The top, gold-coloured layer was cut back (reverse appliqué) in visually related but disconnected shapes to reveal the lower, purple layer. Cords, heavy cotton threads and gold passing thread were couched on using space-dyed threads. A fabric and thread-covered wire, formed into similar shapes, was stitched in an asymmetric position above the main design.

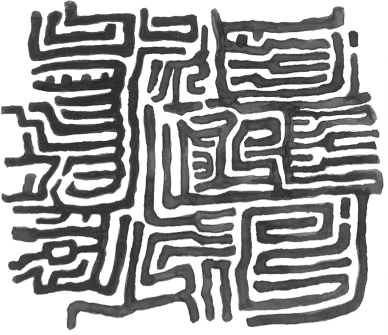

These complex, dislocated patterns are endlessly fascinating because they seem to demand that we continue to study them, following their rhythms and perhaps trying to solve their mysteries. In nature they may be seen in certain crystal formations, in corals and in the fragmented patterns on the surface of some viscous liquids, for example.

This all-white sample was worked in wrapped cords and fine paper thread couched with silk thread on a delicate synthetic mesh.

Characterized by sharply defined forms, these beautiful patterns, which are often very rich in colour, grow from a centre. The circular elements often cluster together, giving a strong impression of density and movement contrasting with the spaces sometimes seen between the groups. These patterns are found in various places, such as the growth patterns of some lichens and the rings in the cross-section of a tree trunk as well as in semi-precious stones like agates, where they are gradually formed by mineral deposits left behind as a result of water seepage.

Bold pattern of circles densely hand-stitched with silk and cotton threads on a painted cotton background. The stitches used were couching, buttonhole stitch, running stitch, split stitch and small straight stitches.

Subtle design of overlapping circles built up entirely from different sizes of straight stitches radiating outwards. Some centres had a small piece of painted silk applied before the stitching was carried out.

Some features of the patterns in this group have much in common with meandering patterns but they are constantly changing. Due to natural forces, such as wind and tide currents working upon the sand from which they are formed, the raised surface of these patterns have a surprising sense of order and repeating rhythms. They are usually found on the shore once the tide has receded and also in desert regions. Some rock formations have similar patterns. These are mostly the sedimentary rocks, formed layer upon layer over time, with the weight of further layers pressing down on them until they are basically compressed into rock. The wonderful sandstone rock formations found in places like Arizona are excellent examples.

Sample worked in the Kantha quilting style on lightly padded, space-dyed silk. Many close rows of tightly tensioned running stitch were worked in a fine thread horizontally across the work. The stitches are slightly shorter than the spaces between them so that the plain background fabric stands up as ripples. The meandering vertical lines were formed by gradually moving each line of stitches over a little, rather than placing them exactly below those of the preceding line.

Sample worked by both hand- and machine stitching. Stretched shirring elastic was hand-wound onto a machine bobbin for the lower thread and a normal machine thread was used as the top thread. Several parallel, shallow zigzag lines were then stitched on cotton fabric that was tightly stretched in an embroidery hoop. Once released the raised chevrons formed as the elastic relaxed were gently touched with gold paint (see right-hand side of sample). These ripples were further enhanced by small, tightly worked whip stitches hand-stitched in fine cotton.

‘The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious.

It is the source of all true art and science.’

Albert Einstein (German physicist 1879–1955)

It would be remiss, when thinking of pattern in nature if reference, albeit brief, was not made to fractals, the study of which has been called a ‘new geometry’. The name derives from the Latin fractus, which means ‘fractured, fragmented or broken’.

Although the concept had been known for some time, the term was not used until 1975 when Polish-born mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot (1924–2010), in his extensive studies of the subject, described it:

‘A geometry able to include mountains and clouds now exists. I put it together in 1975, but of course it incorporates numerous pieces that have been around for a very long time. Like everything in science, this new geometry has very deep and long roots.’

Since then scientists have used the theory of fractals to find and demonstrate mathematically the order in natural structures that had previously been thought of as merely irregular. Not all irregular shapes are fractals – indeed, to fit the category, a shape or pattern must have what Mandelbrot called ‘self similarity’, meaning that every detail, irrespective of scale, must resemble the whole picture. So enlarged or magnified details of an object or a shape will look very much like the larger full-scale view. This means that when graduating from large to small, or vice versa, the details of a pattern or form are countlessly repeated. When these are very large, for example cloud or coastline formations, they may be difficult to recognize, or when very small they may not be apparent when viewed with the naked eye.

The new classification, fractal geometry, has allowed some familiar pattern characteristics in nature, such as branching, undulating, swirling and rippling patterns, to be analyzed and quantified mathematically. Once we understand the order and distinctive qualities of fractal forms, and recognize in their intricacy that they are not simply random or irregular patterns, we can begin to identify many in our surroundings. Good examples are snowflakes as well as the growth forms in ferns and lichens.

The mystery and visual beauty of many fractals, particularly those very colourful ones produced digitally, readily presents the possibly for them to be used as inspiration for our work in stitched textiles. For those who are interested in mathematics and working with the computer, the hugely complex calculations involved in accurately generating fractal design can more easily be managed digitally.

FURTHER WORK

• Take note of examples of natural pattern in your surroundings. Look closely, perhaps with the aid of a magnifying glass.

• Begin your own Pattern Archive, in a sketchbook or folder, with drawings and photographs of natural patterns you observe.

• Using the pattern groups given in this chapter, can you identify where your examples belong?

• Try interpreting your pattern examples by making small exploratory stitch samples.