Why Science and Reason Are the Drivers of Moral Progress

Science, the partisan of no country, but the beneficent patroness of all, has liberally opened a temple where all may meet. Her influence on the mind, like the sun on the chilled earth, has long been preparing it for higher cultivation and further improvement. The philosopher of one country sees not an enemy in the philosophy of another: he takes his seat in the temple of science, and asks not who sits beside him.

—Thomas Paine, 17781

In the 1970s, the NBC comedy series Saturday Night Live featured skits by the comedian and author Steve Martin, whose recurring roles as Theodoric of York, Medieval Barber and Medieval Judge, tapped into the tacit knowledge of moral progress since the Middle Ages—assumed to be held by even late-night viewers. Martin played a barber surgeon who employed bloodletting and other barbaric practices to cure any and all illnesses; as he explained to the mother of one of his patients, “You know, medicine is not an exact science, but we are learning all the time. Why, just fifty years ago they thought a disease like your daughter’s was caused by demonic possession or witchcraft. But nowadays we know that Isabelle is suffering from an imbalance of bodily humors, perhaps caused by a toad or a small dwarf living in her stomach.” The mother didn’t buy it and blasted him for his still-barbaric bloodletting ways until Theodoric had a moment of scientific enlightenment … almost:

Wait a minute. Perhaps she’s right. Perhaps I’ve been wrong to blindly follow the medical traditions and superstitions of past centuries. Maybe we barbers should test these assumptions analytically, through experimentation and a “scientific method.” Maybe this scientific method could be extended to other fields of learning: the natural sciences, art, architecture, navigation. Perhaps I could lead the way to a new age, an age of rebirth, a Renaissance.… Nah!

As the Medieval Judge, Theodoric of York had a similar near-awakening after passing judgment on an accused witch based on the classic trial by ordeal—specifically, in this instance, the ordeal by water. This particular test involved tying up the accused and then dunking her into a body of water. If the accused sank (and drowned) that meant she was innocent; but if she managed to float, she was obviously guilty—either because the pure element of water naturally expels evil or because, in the words of an observer at the time, “the witch, having made a compact with the devil, hath renounced her baptism, hence the antipathy between her and water,”2 or because only by employing her demonic powers could she overcome the weight of the stones with which some of the hapless accused were unfairly burdened. In the case of the accused in Theodoric’s court, the woman proves to be innocent, and thus sinks to her death. The mother, naturally, is furious, proclaiming, “You call this justice!? An innocent girl dead?” Theodoric ponders the mother’s protestations, thinking:

Wait a minute—perhaps she’s right. Maybe the King doesn’t have a monopoly on the truth. Maybe he should be judged by his peers. Oh! A jury! A jury of his peers … everyone should be tried by a jury of their peers and be equal before the law. And perhaps, every person should be free from cruel and unusual punishment.… Nah!3

THE WITCH THEORY OF CAUSALITY

Compressed into these comedic vignettes are centuries of intellectual advancement, from the medieval worldview of magic and superstition to the modern age of reason and science. It is evident that most of what we think of as our medieval ancestors’ barbaric practices were based on mistaken beliefs about how the laws of nature actually operate. If you—and everyone around you, including ecclesiastical and political authorities—truly believe that witches cause disease, crop failures, sickness, catastrophes, and accidents, then it is not only a rational act to burn witches, it is also a moral duty. This is what Voltaire meant when he wrote that people who believe absurdities are more likely to commit atrocities. An even more pertinent translation of his famous quote is relevant here: “Truly, whoever is able to make you absurd is able to make you unjust.”4

Consider a popular thought experiment and how you would respond in the following scenario: You are standing next to a fork in a railroad line and a switch to divert a trolley car that is about to kill five workers on the track unless you throw the switch and divert the trolley down a side track, where it will kill one worker. Would you throw the switch to kill one but save five? Most people say that they would.5 We should not be surprised, then, that our medieval ancestors performed the same kind of moral calculation in the case of witches. Medieval witch burners torched women primarily out of a utilitarian calculus—better to kill the few to save the many. Other motives were present as well, of course, including scapegoating, the settling of personal scores, revenge against enemies, property confiscation, the elimination of marginalized and powerless people, and misogyny and gender politics.6 But these were secondary incentives grafted on to a system already in place that was based on a faulty understanding of causality.

The primary difference between these premodern people and us is, in a word, science. Frankly, they often had not even the slightest clue what they were doing, operating as they were in an information vacuum, and they had no systematic method to determine the correct course of action either. The witch theory of causality, and how it was debunked through science, encapsulates the larger trend in the improvement of humanity through the centuries by the gradual replacement of religious supernaturalism with scientific naturalism. In his sweeping survey of traditional societies, The World Until Yesterday, the evolutionary biologist and geographer Jared Diamond explains how our prescientific ancestors dealt with the problem of understanding causality:

An original function of religion was explanation. Pre-scientific traditional peoples offer explanations for everything they encounter, of course without the prophetic ability to distinguish between those explanations that scientists today consider natural and scientific, and those others that scientists now consider supernatural and religious. To traditional peoples, they are all explanations, and those explanations that subsequently became viewed as religious aren’t something separate. For instance, the New Guinea societies in which I have lived offer many explanations for bird behavior that modern ornithologists consider perceptive and still accurate (e.g., the multiple functions of bird calls), along with other explanations that ornithologists no longer accept and now dismiss as supernatural (e.g., that songs of certain bird species are voices of former people who became transformed into birds).7

In my book Why People Believe Weird Things I review the extensive scientific literature concerning the role of superstition in pre- or nonscientific societies. The Trobrianders, for example, who live on islands near Papua New Guinea, employed weather magic, healing magic, garden magic, dance magic, love magic, sailing and canoe magic, and especially fishing magic. In the calm waters of the inner lagoon where a catch is much more likely and safer, there are few superstitious rituals. By contrast, in preparation for the uncertain waters of deep sea fishing the Trobrianders perform many magical rituals, including whispering and murmuring magical formulas. The anthropologist Gunter Senft has cataloged many such verbal utterances, such as one called Yoya’s fish magic, which he recorded in 1989 and that involved the repetition of certain phrases:8

Totwaieee |

Tokwai |

kubusi kuma kulova |

come down, come, come inside |

o bwalita bavaga |

to the sea I will return |

kubusi kuma kulova |

come down, come, come inside |

o bwalita a’ulova |

at sea I put a spell in [it] |

A seven-second pause is then followed by another series of related phrases, all toward an end of “ordering and commanding their addressees to do or change something, or by foretelling changes, processes, and developments that are necessary for reaching these aims,” Senft writes. The anthropologist who published the first and definitive ethnography on the Trobriand Islanders, Bronislaw Malinowski, concluded that his charges were misinformed, not ignorant. Magic, he said, is “to be expected and generally to be found whenever man comes to an unbridgeable gap, a hiatus in his knowledge or in his powers of practical control, and yet has to continue in his pursuit.”9 The solution to magical thinking, then, is to close those unbridgeable gaps with scientific thinking.

Other anthropologists have made similar discoveries about their subjects, such as E. E. Evans-Pritchard in his classic study Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic Among the Azande, a traditional society in the southern Sudan in Africa. After a survey of the many bizarre beliefs about witches held by the Azande, Evans-Pritchard explains the psychology behind witchcraft beliefs, starting with the fact that “Witches, as the Azande conceive them, clearly cannot exist. Nonetheless, the concept of witchcraft provides them with a natural philosophy by which the relations between men and unfortunate events are explained and a ready and stereotype means of reacting to such events.” Here we see in a premodern society what happens when magical thinking goes unchecked by critical thinking:

Witchcraft is ubiquitous. It plays its part in every activity of Zande life; in agricultural, fishing, and hunting pursuits; in domestic life of homesteads as well as in communal life of district and court; it is an important theme of mental life in which it forms the background of a vast panorama of oracles and magic;… there is no niche or corner of Zande culture into which it does not twist itself. If blight seizes the ground-nut crop it is witchcraft; if the bush is vainly scoured for game it is witchcraft; if women laboriously bale water out of a pool and are rewarded by but a few small fish it is witchcraft; if a wife is sulky and unresponsive to her husband it is witchcraft; if a prince is cold and distant with his subject it is witchcraft; if, in fact, any failure or misfortune falls upon anyone at any time and in relation to any of the manifold activities of his life it may be due to witchcraft.10

Nowadays, science has all of these problems covered. We know that crops can fail due to disease, which we study through the science of agronomy and the etiology of disease; or they fail due to insects that we can investigate through the science of entomology and further control through chemistry; or they fail due to inclement weather that we can understand through the science of meteorology. Ecologists and biologists can tell us why populations of fish rise and fall and what we can do to prevent a region being fished out or decimated by disease or climate change. Psychologists specializing in marital counseling can explain why a wife might not be as responsive as her husband may wish (and vice versa); and though there may not be a big call for this sort of thing these days, psychologists who study personality and temperament could explain why some princes are cold and distant while others are warm and connected to their subjects. Statisticians and risk analysts can assess the rates of failure and misfortune that might befall anyone at any time in relation to any number of activities of life, well captured in the ne plus ultra of pop-culture, bumper-sticker philosophy—“Shit Happens.”

Tellingly, Evans-Pritchard notes that the Zande do not attribute everything that happens to witchcraft—only those things for which they do not have a plausible-sounding causal explanation. “In Zandeland sometimes an old granary collapses. There is nothing remarkable in this. Every Zande knows that termites eat the supports in course of time and that even the hardest woods decay after years of service.” But when a group of people are sitting inside the granary when it collapses and they are injured, the Zande wonder, in Evans-Pritchard’s description, “why should these particular people have been sitting under this particular granary at the particular moment when it collapsed? That it should collapse is easily intelligible, but why should it have collapsed at the particular moment when these particular people were sitting beneath it?” Evans-Pritchard then draws the distinction between prescientific and scientific worldviews:

To our minds the only relationship between these two independently caused facts is their coincidence in time and space. We have no explanation of why the two chains of causation intersected at a certain time and in a certain place, for there is no interdependence between them. Zande philosophy can supply the missing link. The Zande knows that the supports were undermined by termites and that people were sitting beneath the granary in order to escape the heat and glare of the sun. But he knows besides why these two events occurred at a precisely similar moment in time and space. It was due to the action of witchcraft. If there had been no witchcraft people would have been sitting under the granary and it would not have fallen on them, or it would have collapsed but the people would not have been sheltering under it at the time. Witchcraft explains the coincidence of these two happenings.11

A witch is a causal theory of explanation. And it’s fair to say that if your causal theory to explain why bad things happen is that your neighbor flies around on a broom and cavorts with the devil at night, inflicting people, crops, and cattle with disease, preventing cows from giving milk, beer from fermenting, and butter from churning—and that the proper way to cure the problem is to burn her at the stake—then either you are insane or you lived in Europe six centuries ago, and you even had biblical support, specifically Exodus 22:18: “Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live.” Witches were believed to be able to inflict harm on others just by staring at them—giving them “the evil eye”—thereby releasing an invisible but potent emanation, especially if she was menstruating.

Figure 3-1.

Four women being interrogated for witchcraft in the attempted murder of King James I.

Figure 3-1 shows four women being interrogated for witchcraft in the attempted murder of King James I. One of them, a woman named Agnes Sampson, confessed under torture that she had danced counterclockwise, which was believed to lead to disaster. Witch-hunters developed techniques to determine the guilt or innocence of accused witches, including searching their bodies for telltale marks of their cavorting with the devil.

Again, the point is not that our medieval ancestors were irrational in their magical thinking. To the contrary, they fully believed that what they were doing in employing various magical incantations, spells, and superstitions of various sorts would have the desired effect. As the medieval historian Richard Kieckhefer notes, the people of medieval Europe thought of magic as rational for two reasons: “first of all, that it could actually work (that its efficacy was shown by evidence recognized within the culture as authentic) and, secondly, that its workings were governed by principles (of theology or of physics) that could be coherently articulated.”12 It was the Roman Catholic Church that first articulated the witch theory of causality in medieval Europe with the Papal Bull of Innocent VIII in 1484, Summis Desiderantes Affectibus (Desiring with Supreme Ardor), followed two years later with the Catholic clergyman Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of the Witch). The latter was a how-to manual on finding and prosecuting witches, who, it alleged, were able to copulate with the devil, steal men’s penises, wreck ships, ruin crops, eat babies, turn men into frogs, shed no tears, cast no shadow in the sun, have hair that could not be cut, and pretty much anything considered to be “devilish” and “wicked.”

The manual instructed investigators on how to look for the witch’s mark—a spot or excrescence on her body that supposedly did not bleed when pricked (giving rise, as one can imagine, to inappropriate touching by the mostly male investigators of the mostly female suspects). Finding witches not only explained evil, it also was tangible evidence of God’s existence. As the sixteenth-century Cambridge theologian Roger Hutchinson argued, in a polished bit of circular reasoning, “If there be a God, as we most steadfastly must believe, verily there is a Devil also; and if there be a Devil, there is no surer argument, no stronger proof, no plainer evidence, that there is a God.”13 And, conversely, as noted in a seventeenth-century witch trial, “Atheists abound in these days and witchcraft is called into question. If neither possession nor witchcraft [exists], why should we think that there are devils? If no devils, no God.”14

Figure 3-2 is a woodcut illustration from the title page of a pamphlet titled Witches Apprehended, Examined and Executed, published in 1613. It shows the classic “trial by ordeal” or “ordeal by water.” Pictured is a woman named Mary Sutton being put to the test in 1612.

Today, the witch theory of causality has fallen into disuse, with the exception of a few isolated pockets in Papua New Guinea, India, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Ghana, Gambia, Tanzania, Kenya, or Sierra Leone, where “witches” are still burned to death. A 2002 World Health Organization study, for example, reported that every year more than 500 elderly women in Tanzania alone are killed for being “witches.” In Nigeria, children by the thousands are being rounded up and torched as “witches,” and in response the Nigerian government arrested a self-styled bishop named Okon Williams, who it accused of killing 110 such children.15 Another study found that as many as 55 percent of sub-Sahara Africans believe in witches.16 And such wrong beliefs can kill. On February 6, 2013, a twenty-year-old woman and mother of two named Kepari Leniata was burned alive in the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea because she was accused of sorcery by the relatives of a six-year-old boy who died on February 5.17 As in witch hunts of old, the conflagration on a pile of rubbish was preceded by torture with a hot iron rod, after which Kepari was bound and doused in gasoline and ignited while surrounded by gawking crowds that prevented police and authorities from rescuing her. A 2010 Oxfam study explains why sorcery and witchcraft are not uncommon in this part of the world in which many people still “do not accept natural causes as an explanation for misfortune, illness, accidents or death,” and instead place the blame for their problems on supernatural sorcery and black magic.18

Figure 3-2.

From the title page of Witches Apprehended, Examined and Executed, published in 1613. It shows the classic “ordeal by water.”

Are these people evil or misinformed? By modern Western moral standards, of course, they’re morally reprehensible and, if living in places where witchcraft and the burning of alleged witches is illegal, they are also criminal. But given the fact that Europeans and Americans abandoned their belief in witches when science supplanted superstition as a better explanation for evil (and it was outlawed), the generous assessment is that these witch-hunters are merely misinformed. In short, they hold a wrong theory of causality. That said, it is not just a matter of improving science education, although an education of any sort would be a good start for all sorts of reasons, both moral and practical. For starters, governments must outlaw the burning of witches. Jared Diamond tells me that in Papua New Guinea the extraordinarily high rate of violence—including witch burning—was greatly attenuated by government agents going from village to village and outlawing such diabolical practices, confiscating weapons, and laying down the law.

A poignant example of what it often takes to bring about an end to a superstitious barbaric act may be seen in the Indian practice of suttee, or the burning of widows. The British government abolished suttee by outlawing it, and followed up by severely punishing transgressors. As the nineteenth-century British commander in chief in India, General Charles Napier, told his charges who complained that suttee was their cultural custom that the British should respect: “Be it so. This burning of widows is your custom; prepare the funeral pile. But my nation has also a custom. When men burn women alive we hang them, and confiscate all their property. My carpenters shall therefore erect gibbets on which to hang all concerned when the widow is consumed. Let us all act according to national customs.”19

In the long run, however, external restrictions in the form of laws must be supplemented with internal controls in the form of ideas. An example of how the witch theory of causality was tested and debunked in Germany is recounted by Charles MacKay in his classic work Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. At the height of the witch craze the Duke of Brunswick invited two learned and famous Jesuits—both of whom believed in witchcraft and in torture as a means of eliciting a confession—to join him in the Brunswick dungeon to witness the torture of a woman accused of witchcraft. Suspecting that people will say anything to stop the pain, the duke told the woman on the rack that he had reasons to believe that the two men accompanying him were warlocks and that he wanted to know what she thought, instructing her torturers to jack up the pain a little more. The woman promptly “confessed” that she had seen both men turn themselves into goats, wolves, and other animals, that they had sexual relations with other witches, and that they had fathered many children with heads like toads and legs like spiders. “The Duke of Brunswick led his astounded friends away,” MacKay narrates. “This was convincing proof to both of them that thousands of persons had suffered unjustly; they knew their own innocence, and shuddered to think what their fate might have been if an enemy instead of a friend had put such a confession into the mouth of a criminal.”20

One of these Jesuits was Friedrich Spee, who in response to this shocking display of induced false confessions published a book in 1631 called Cautio Criminalis, which exposed the horrors of the torturous witch trials. This led the archbishop and elector of Menz, Schonbrunn, to abolish torture entirely, which in turn led to the abolition of torture for witchcraft elsewhere—a catalyst in the cascading effect that caused the witch mania to collapse. “This was the beginning of the dawn after the long-protracted darkness,” Mackay writes. “The tribunals no longer condemned witches to execution by hundreds in a year. A truer philosophy had gradually disabused the public mind. Learned men freed themselves from the trammels of a debasing superstition, and governments, both civil and ecclesiastical, repressed the popular delusion they had so long encouraged.”21

Before the dawn broke, however, thousands of people were senselessly murdered. Precise figures are hard to come by—given the spottiness of the record—but the historian Brian Levack puts the figure at sixty thousand, based on the number of trials and the rate of convictions (often close to 50 percent),22 while the medieval historian Anne Llewellyn Barstow adjusts that figure upward to one hundred thousand, based on lost records.23 Figure 3-3 is a depiction by the Dutch artist Johannes Jan Luyken of a woman named Anneken Hendriks who is about to be burned to death as a witch in 1571.

Figure 3-3.

Anneken Hendriks, a woman accused of witchcraft, about to be burned to death in 1571.

Whatever the tally, it was a tragically high number, and after the immediate solution of banning it, the ultimate solution to ending witchcraft everywhere proved to be a better understanding of causality: science. As the historian Keith Thomas concludes in his sweeping history Religion and the Decline of Magic, the first and most important factor in the decline “was the series of intellectual changes which constituted the scientific and philosophical revolution of the seventeenth century. These changes had a decisive influence upon the thinking of the intellectual élite and in due course percolated down to influence the thought and behavior of the people at large. The essence of the revolution was the triumph of the mechanical philosophy.”24

By “mechanical philosophy” Thomas means the Newtonian clockwork universe, the worldview that holds that all effects have natural causes and the universe is governed by natural laws that can be examined and understood. In this worldview there is no place for the supernatural, and that is what ultimately doomed the witch theory of causality, along with other supernatural explanations. “The notion that the universe was subject to immutable natural laws killed the concept of miracles, weakened the belief in the physical efficacy of prayer, and diminished faith in the possibility of direct divine inspiration,” Thomas concludes. “The triumph of the mechanical philosophy meant the end of the animistic conception of the universe which had constituted the basic rationale for magical thinking.”25

There were other factors at work besides reason and science that I discuss below, but my point here is that beliefs such as witchcraft are not immoral so much as they are mistaken. In the West, science debunked the witch theory of causality, as it has and continues to discredit other superstitious and religious ideas. We refrain from burning women as witches not because our government prohibits it, but because we do not believe in witches and therefore the thought of incinerating someone for such practices never even enters our minds. What was once a moral issue is now a nonissue, pushed out of our consciousness—and our conscience—by a naturalistic, science- and reason-based worldview.

LIFE BEFORE SCIENCE

The witch theory of causality—a catchall explanation for the miseries of life—was hardly up to the formidable task of elucidation given that there was just so much misery to explain. To fully feel the change let’s go back to a time when civilization was lit only by fire, five centuries ago when populations were sparse and 80 percent of people lived in the countryside and were engaged in food production, largely for themselves. Cottage industries were the only industries in this preindustrial and highly stratified society, in which a third to half of the population lived at subsistence level and were chronically underemployed, underpaid, and undernourished. Food supplies were unpredictable, and plagues decimated weakened populations. In the century spanning 1563 to 1665, for example, there were no fewer than six major epidemics that swept through London, each of which annihilated between a tenth and a sixth of the population. The death tolls are almost unimaginable by today’s standards: 20,000 in 1563, 15,000 in 1593, 36,000 in 1603, 41,000 in 1625, 10,000 in 1636, and 68,000 in 1665, all in one of the world’s major metropolitan cities whose population was around 120,000 in 1550, 200,000 in 1600, and 400,000 in 1650, so the percentage of deaths during each plague was substantial. Childhood diseases were unforgiving, felling 60 percent of children before age 17. As one observer noted in 1635, “We shall find more who have died within thirty or thirty-five years of age than passed it.”26 The historian Charles de La Roncière provides examples from fifteenth century Tuscany in which lives were routinely cut short:

Many died at home: children like Alberto (aged ten) and Orsino Lanfredini (six or seven); adolescents like Michele Verini (nineteen) and Lucrezia Lanfredini, Orsino’s sister (twelve); young women like beautiful Mea with the ivory hands (aged twenty-three, eight days after giving birth to her fourth child, who lived no longer than the other three, all of whom died before they reached the age of two); and of course adults and elderly people.27

And this does not include, La Roncière adds parenthetically, the deaths of newborns, which historians estimate could have been as high as 30 to 50 percent.28

Since magical thinking is positively correlated with uncertainty and unpredictability,29 we should not be surprised at the level of superstition given the grim vagaries of premodern life. There were no banks for people to set up personal savings accounts during times of plenty to provide a cushion of comfort during times of scarcity. There were no insurance policies for risk management, and few people had much personal property to insure anyway. With homes constructed of thatched roofs and wooden chimneys in a night lit only by candles, fires would routinely devastate entire neighborhoods. As one chronicler noted, “He which at one o’clock was worth five thousand pounds and, as the prophet saith, drank his wine in bowls of fine silver plate, had not by two o’clock so much as a wooden dish left to eat his meat in, nor a house to cover his sorrowful head.”30 Alcohol and tobacco became essential anesthetics for the easing of pain and discomfort that people employed as a form of self-medication, along with the belief in magic and superstition to mitigate misfortune.

Under such conditions it’s no wonder that almost everyone believed in sorcery; werewolves; hobgoblins; astrology; black magic; demons; prayer; providence; and, of course, witches and witchcraft. As Bishop Hugh Latimer of Worcester explained in 1552, “A great many of us, when we be in trouble, or sickness, or lose anything, we run hither and thither to witches, or sorcerers, whom we call wise men … seeking aid and comfort at their hands.”31 Saints were invoked and liturgical books provided rituals for blessing cattle, crops, houses, tools, ships, wells, and kilns, along with special prayers for sterile animals, the sick and infirm, and even infertile couples. In his 1621 book Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton noted, “Sorcerers are too common; cunning men, wizards, and white witches, as they call them, in every village, which, if they be sought unto, will help almost all infirmities of body and mind.”32

Was everyone in the prescientific world so superstitious? They were. As the historian Keith Thomas notes, “No one denied the influence of the heavens upon the weather or disputed the relevance of astrology to medicine or agriculture. Before the seventeenth century, total skepticism about astrological doctrine was highly exceptional, whether in England or elsewhere.” And it wasn’t just astrology. “Religion, astrology and magic all purported to help men with their daily problems by teaching them how to avoid misfortune and how to account for it when it struck.” With such sweeping power over people, Thomas concludes, “If magic is to be defined as the employment of ineffective techniques to allay anxiety when effective ones are not available, then we must recognize that no society will ever be free from it.”33

That may well be, but the rise of science diminished this near universality of magical thinking by proffering natural explanations where before there were predominately supernatural ones. The decline of magic and the rise of science was a linear ascent out of the darkness and into the light. As empiricism gained status there arose a drive to find empirical evidence for superstitious beliefs that previously needed no propping up with facts.

This attempt to naturalize the supernatural carried on for some time and spilled over into other areas. The analysis of portents was often done meticulously and quantitatively, albeit for purposes both natural and supernatural. As one diarist privately opined on the nature and meaning of comets, “I am not ignorant that such meteors proceed from natural causes, yet are frequently also the presages of imminent calamities.”34 Yet the propensity to portend the future through magic led to more formalized methods of ascertaining causality by connecting events in nature—the very basis of science. In time, natural theology became wedded to natural philosophy and science arose out of magical beliefs, which it ultimately displaced. By the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, astronomy replaced astrology, chemistry succeeded alchemy, probability theory displaced luck and fortune, insurance attenuated anxiety, banks replaced mattresses as the repository of people’s savings, city planning reduced the risks from fires, social hygiene and the germ theory dislodged disease, and the vagaries of life became considerably less vague.

FROM THE PHYSICAL SCIENCES TO THE MORAL SCIENCES

To the debunking of the witch theory of causality and the general improvement in living conditions, we can add as promoters of moral progress the general application of reason and science to all fields, including governance and the economy. This shift was the result of two intellectual revolutions: (1) the Scientific Revolution, dated roughly from the publication of Copernicus’s On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres in 1543 to the publication of Isaac Newton’s Principia in 1687; and (2) the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment, dated from approximately 1687 to 1795 (Newton to the French Revolution). The Scientific Revolution led directly to the Enlightenment, as intellectuals in the eighteenth century sought to emulate the great scientists of the previous centuries in applying the rigorous methods of the natural sciences and philosophy to explaining phenomena and solving problems. This marriage of philosophies resulted in Enlightenment ideals that placed supreme value on reason, scientific inquiry, human natural rights, liberty, equality, freedom of thought and expression, and on a diverse, cosmopolitan worldview that most people today embrace—a “science of man,” as the great Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume called it.

From an intellectual history perspective, I have described this shift as the “battle of the books”—the book of authority vs. the book of nature.35 The book of authority—whether it was the Bible or Aristotle in the Western world—is grounded in the cognitive process called deduction, or making specific claims from generalized principles, or arguing from the general to the specific. By contrast, the book of nature is grounded in induction, or the cognitive process of drawing generalized principles from specific facts, or arguing from the specific to the general. None of us—nor any tradition—practices pure induction or pure deduction, but the Scientific Revolution was revolting against the overemphasis on the book of authority, and instead promoted an insistence on checking one’s assumptions with the book of nature.

For example, one of the giants of the Scientific Revolution—Galileo Galilei—got himself in hot water with the Church partly for insisting on observation as the gold standard, rather than blind acceptance, in order to determine if the ancient authorities were correct in their conjectures. “The authority of Archimedes was of no more importance than that of Aristotle,” he said. “Archimedes was right because his conclusions agreed with experiment.”36

It’s a matter of balance between deduction and induction—between reason and empiricism—and in 1620 the English philosopher Francis Bacon published his Novum Organum, or “new instrument,” which described science as a blend of sensory data and reasoned theory. Ideally, Bacon argued, one should begin with observations, then formulate a general theory from which logical predictions can be made, then check the predictions against experiment.37 If you don’t give yourself a reality check you end up with half-baked (and often fully baked) ideas, such as the ancient Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder’s “Remedies for Ulcerous Sores and Wounds” from his first-century CE book The Natural History, which reads like a skit from Monty Python:

With sheep’s dung, warmed beneath an earthen pan and kneaded, the swellings attendant upon wounds are reduced, and fistulous sores and epinyctis are cleansed and made to heal. But it is in the ashes of a burnt dog’s head that the greatest efficacy is found; as it quite equals spodium in its property of cauterizing all kinds of fleshy excrescences, and causing sores to heal. Mouse-dung, too, is used as a cautery, and weasels’ dung, burnt to ashes.38

In France, the philosopher and mathematician René Descartes—considered to be the founder of modern philosophy—set himself the momentous (and one should have thought impossible) task of unifying all knowledge so as to “give the public … a completely new science which would resolve generally all questions of quantity.” In his 1637 skeptical work Discourse on Method, Descartes instructed readers to take as false what was probable, to take as probable what was certain, and to discard everything else that relied on old books and authorities.

Doubting everything, Descartes famously concluded that there was one thing he could not doubt, and that was his own thinking mind: “Cogito, ergo sum—I think, therefore I am.” Building from this first principle he turned to mathematical reasoning and from there built not only a new branch of mathematics (the Cartesian coordinate system in common use today) but also a new and powerful science that could be applied to any subject. Descartes’s work generated an esprit géométrique and an esprit du mechanism (a spirit of geometry and a spirit of mechanical causation) to find mathematical and mechanical explanations for everything. This mechanical philosophy gained international credibility through Newton’s clockwork universe. This embrace of mathematical precision is still visible today in the gardens of France with their geometric regularity. There Descartes became fascinated with the mechanical automata he saw operating under hydraulic pressure, and this esprit led to his (and others) turning to mechanical explanations for animals and humans.39

The watershed event that changed everything, however, was the publication in 1687 of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, which synthesized the physical sciences and which his contemporaries declared to be “the premier production of the human mind” (Joseph-Louis Lagrange) and a work that “has a pre-eminence above all other productions of the human intellect” (Pierre-Simon Laplace). Upon Newton’s death, Alexander Pope eulogized Newton thusly: “Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night. God said let Newton be! And all was light.” The Enlightenment luminary David Hume described Newton as “the greatest and rarest genius that ever rose for the adornment and instruction of the species.”40

Newton showed that the rigorous methods of mathematics and science could be applied to all fields. And he practiced what he preached, making significant contributions to pure and applied mathematics (he invented the calculus), optics, the law of universal gravity, tides, heat, the chemistry and theory of matter, alchemy, chronology, interpretation of Scripture, the design of scientific instruments, and even the minting of money. After the precisely predicted return of Halley’s comet confirmed Newton’s theory of universal gravitation, the race was on to apply Newtonian methods of science to all fields. “Men and women everywhere saw a promise that all of human knowledge and the regulation of human affairs would yield to a similar rational system of deduction and mathematical inference coupled with experiment and critical observation,” notes the great historian of science Bernard Cohen. “Newton was the symbol of successful science, the ideal for all thought—in philosophy, psychology, government, and the science of society.”41

The Scientific Revolution that culminated in Newtonian science led scientists in diverse fields to strive to be the Newton of their own particular science. In his 1748 work Esprit des Lois (The Spirit of the Laws), for example, the French philosophe Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu—known simply as Montesquieu—consciously invoked Newton when he compared a well-functioning monarchy to “the system of the universe” that includes “a power of gravitation” that “attracts” all bodies to “the center” (the monarch). And his method was the deductive method of Descartes: “I have laid down first principles and have found that the particular cases follow naturally from them.” By “spirit” Montesquieu meant “causes” from which one could derive “laws” that govern society. “Laws in their most general signification, are the necessary relations derived from the nature of things,” he wrote. “In this sense all beings have their laws, the Deity has his laws, the material World its laws, the intelligences superior to man have their laws, the beast their laws, man his laws.”

As a young man Montesquieu published a number of scientific papers on a wide range of topics—tides, fossil oysters, the function of kidneys, causes of echoes—and in Esprit des Lois he applied his naturalistic talents to produce a theory of the natural conditions that led to the development of the different governments and legal systems throughout the world, such as the climate, the quality of the soil, the religion and occupation of the inhabitants, their numbers, commerce, manners, customs, and the like. His typology included four types of societies: hunting, herding, agriculture, and trade or commerce, with legal systems becoming ever more complex. “The laws have a very great relation to the manner in which the several nations procure their subsistence,” he wrote. “There should be a code of laws of a much larger extent for a nation attached to trade and navigation than for people who are content with cultivating the earth. There should be a much greater for the latter than for those who subsist by their flocks and herds. There must be a still greater for these than for such as live by hunting.” This led Montesquieu to become one of the earliest proponents of the trade theory of peace when he observed that hunting and herding nations often found themselves in conflict and wars, whereas trading nations “became reciprocally dependent,” making peace “the natural effect of trade.” The psychology behind the effect, Montesquieu speculated, was exposure of different societies to customs and manners different from their own, which leads to “a cure for the most destructive prejudices.” Thus, he concluded, “we see that in countries where the people move only by the spirit of commerce, they make a traffic of all the humane, all the moral virtues.”42

Following in the natural law tradition of Montesquieu, a group of French scientists and scholars known as the physiocrats declared that all “social facts are linked together in necessary bonds eternal, by immutable, ineluctable, and inevitable laws” that should be obeyed by people and governments “if they were once made known to them” and that human societies are “regulated by natural laws … the same laws that govern the physical world, animal societies, and even the internal life of every organism.” One of these physiocrats, François Quesnay—a physician to the king of France who later served as an emissary to Napoleon for Thomas Jefferson—modeled the economy after the human body, in which money flowed through a nation like blood flows through a body, and ruinous government policies were like diseases that impeded economic health.43 He argued that even though people have unequal abilities, they have equal natural rights, and so it was the government’s duty to protect the rights of individuals from being usurped by other individuals, while at the same time enabling people to pursue their own best interests. This led them to advocate for private property and a free market. It was, in fact, the physiocrats who gave us the term “laissez-faire”—translated as “leave alone”—the economic practice of minimum government interference in the economic interests of citizens and society.

The physiocrats asserted that people operating in a society were subject to knowable laws of both human and economic nature not unlike those discovered by Galileo and Newton, and this movement grew into the school of classical economics championed by David Hume, Adam Smith, and others and that forms the basis of all economic policy today. The very title of Adam Smith’s monumental 1776 work reveals its scientific emphasis: An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith employed the terms “nature” and “causes” in the scientific sense of identifying and understanding the cause-and-effect relationships in the natural system of an economy, with the underlying premise that natural laws govern economies, that humans are rationally calculating economic actors whose behaviors can be understood, and that markets are self-regulating by an “invisible hand.” The origin of Smith’s famous metaphor was astronomical in nature. As Smith wrote in his little-known work on the history of astronomy,

For it may be observed, that in all Polytheistic religions, among savages, as well as in the early ages of heathen antiquity, it is the irregular events of nature only that are ascribed to the agency and power of the gods. Fire burns, and water refreshes; heavy bodies descend, and lighter substances fly upwards, by the necessity of their own nature; nor was the invisible hand of Jupiter ever apprehended to be employed in those matters.44

Here Smith was describing the invisible hand of gravity, but his later application of the metaphor in the Wealth of Nations implied that an invisible hand appears to guide markets and economies. Smith, it should be noted, was a professor of moral philosophy, and his first great work, published in 1759, was titled A Theory of Moral Sentiments, in which he laid the foundation for the theory that we have an innate sense of morality: “How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others.” The emotion of empathy—what Smith called sympathy—allows us to feel someone else’s joy or agony by imagining ourselves as that person and sensing how we would feel: “As we have no immediate experience of what other men feel, we can form no idea of the manner in which they are affected, but by conceiving what we ourselves should feel in the like situation.”45 This is the principle of interchangeable perspectives at work.

In the arena of governance, another Enlightenment luminary who consciously applied the principles and methods of the physical sciences to the moral sciences was the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose 1651 book Leviathan is considered to be one of the most influential works in the history of political thought. In it Hobbes deliberately modeled his analysis of the social world after the work of Galileo and the English physician William Harvey, whose 1628 De Motu Cordis (On the Motion of the Heart and the Blood) outlined a mechanical model of the workings of the human body. As Hobbes later immodestly reflected, “Galileus … was the first that opened to us the gate of natural philosophy universal, which is the knowledge of the nature of motion.… The science of man’s body, the most profitable part of natural science, was first discovered with admirable sagacity by our countryman, Doctor Harvey. Natural philosophy is therefore but young; but civil philosophy is yet much younger, as being no older … than my own de Cive.”

Hobbes even patterned his Elements of Law after Euclid’s Elements of Geometry, classifying all previous philosophers into two camps: the dogmatici, who for two millennia had failed to create a viable moral or political philosophy; and the mathematici, who proceeded “from most low and humble principles … going on slowly, and with most scrupulous ratiocinations” to create a system of useful knowledge about the social world. And this new system of thought is not “that which makes philosophers’ stones, nor that which is found in the metaphysic codes,” he proclaimed in an epistle to his readers, “but that it is the natural reason of man, busily flying up and down among the creatures, and bringing back a true report of their order, causes and effects.”46

Hobbes self-consciously applied both the esprit géométrique and the esprit du mechanism to the study of nature, man, and “civil governments and the duties of subjects.”47 Here we see both the connection from the physical and biological sciences to the social sciences, and also the point of my focusing on this period in the history of science—our modern concepts of governance arose out of this drive to apply reason and science to any and all problems, including human social problems.

According to the historian of science Richard Olson (my doctoral adviser who first introduced me to these links between science and society), “Hobbes’s theories of nature, man, and society clearly derived their form from a Hobbesian version of the Cartesian esprit géométrique.” Not only that, Olson continues, “Hobbes believed that the sciences of man and society could, like the science of inanimate natural bodies, be constructed on the geometrical or hypothetico-deductive model.”48 The latter is the science philosopher’s term for the modern scientific method, which can be summarized in three steps: (1) formulating a hypothesis based on initial observations, (2) making a prediction based on the hypothesis, and (3) checking or testing whether the prediction is accurate.

Hobbes’s theory of how to build a civil society is a purely naturalistic argument that employed the best science of his day, and Hobbes, along with his Enlightenment colleagues, considered themselves to be practicing what today we call science (but what they called natural philosophy).49 He begins with the assumption that the universe is composed only of material objects that are in motion (such as atoms and planets). The brain detects the movement of these objects through the senses—either directly through, say, touch, or indirectly via the transmission of some energy, as in vision—and all ideas come from these basic sense movements. Humans can sense matter in motion, and humans themselves are in motion (like “the motion of the blood, perpetually circulating” he notes, citing William Harvey), constantly driven by the passions: appetites (pleasures) and aversions (pain). When motion ceases (e.g., blood circulation), life ceases, so all human action is directed toward maintaining the vital motions of life. Pleasure (or delight or contentment), he says, “is nothing really but motion about the heart, as conception is nothing but motion about the head, and the objects which cause it are called pleasant or delightful.”

What we think of as good and bad, then, are directly related to a person’s desires or fears in response to a given stimulus. To gain pleasure and avoid pain one needs power: “The power of a man is his present means to obtain some future apparent good,” Hobbes continues. In a state of nature everyone is free to exert their power over others to gain greater pleasures. This Hobbes calls the Right of Nature. Even though humans have equal ability, they have unequal passions that, he says, “during the time men live without a common power to keep them all in awe, they are in that condition which is called war; and such a war as is of every man against every man.” By war, Hobbes does not just mean actual fighting, but a constant state of fear of fighting, which makes it impossible to plan for the future. As he concluded in one of the most famous (and oft-quoted) passages in all of political theory:

In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.50

But we do not live in a state of nature, says Hobbes, because humans have one more mental property that enables us to rise above the Right of Nature, and that is reason. It is reason that led people to realize that to be free they must surrender all rights to a sovereign in a social contract. This sovereign Hobbes calls the Leviathan, after the powerful Old Testament sea monster.51

Half a century after Hobbes, no scholar of political or economic thought was taken seriously unless they overtly employed a scientific approach to their study, that is, some combination of reason and empiricism to derive conclusions about how humans behave (descriptive observations) and how humans should behave (prescriptive morals) in society. As the Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume colorfully declared toward the end of his classic 1749 work An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding: “If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number? No. Does it contain any experimental reasoning concerning matter of fact and existence? No. Commit it then to the flames: for it can contain nothing but sophistry and illusion.”52 As well, Hobbes’s mechanical model imagined people as atoms—interchangeable particles in a social universe governed by natural laws that can be studied in the same manner as physicists measure atoms or astronomers track planets, and from which general theories can be derived to explain their motions. The eminent modern political philosopher Michael Walzer clarifies what this new way of studying the social world meant: “For two hundred years there is hardly an English writer, hardly a coffee house conversationalist, who is not a successor to Hobbes.”53

FROM IS TO OUGHT: SOCIAL SCIENCE AND MORAL PROGRESS

Whether or not Hobbes was right about the Leviathan origins of the social contract (it’s a mixed history because humans are social creatures and have never lived in isolation), the fact is that the Leviathan state is what emerged over the past half millennium as thousands of tiny municipalities, duchies, baronies, and the like coalesced into ever larger political organizations during the early modern period of state building.

Political scientists estimate that in Europe there were about five thousand political units in the fifteenth century, five hundred in the seventeenth century, two hundred by the eighteenth century, and less than fifty in the twentieth century.54 This coalescence resulted in two major trends: (1) the decline of individual violence in which the percentage of people who die violently in states is significantly lower than that of traditional, prestate societies; and (2) an increase and a decrease in total death counts from 1500 until 1950, in that there was a decrease in the number and duration of great-power wars, but an increase in their intensity (the number of people killed per country per year)—with these two trends pushing in opposite directions, the total death count rose and fell. After the Second World War, however, both the frequency and the intensity of war decreased until, essentially, the world’s great powers quit fighting.

Let’s look at the logic of how the Leviathan works to reduce violence, and transition here from is (how science and reason developed historically) to ought (how this knowledge was—and ought to be—used to bend the moral arc). The Leviathan reduces violence by asserting a monopoly on the legitimate use of force, thereby replacing what criminologists call “self-help justice”—in which individuals settle their own scores and disputes, often violently (such as the Mafia)—with criminal justice, leading overall to a decrease in violence. But there are other factors at work as well.

Trade, Commerce, and Conflict

Hobbes was only partially right in advocating top-down state controls to keep the inner demons of our nature in check. Trade and commerce were also major factors, given the moral and practical benefits of trading for what you need instead of killing to get it. I call this Bastiat’s Principle (after the nineteenth-century French economist Frédéric Bastiat, who first articulated the concept): where goods do not cross frontiers, armies will, but where goods do cross frontiers, armies will not.55 I call it a principle instead of a law because there are exceptions both historically and today. Trade does not prevent war and interstate violence, but it attenuates its likelihood.

As I documented in The Mind of the Market, trade breaks down the natural animosity between strangers while simultaneously elevating trust between them, and as the economist Paul Zak has demonstrated, trust is among the most powerful factors affecting economic growth. In his neuroeconomics lab at Claremont Graduate University, for example, Zak has shown that the trust hormone oxytocin is released during exchange games between strangers, thereby enhancing trust and setting off a positive feedback loop. In addition, the neurotransmitter dopamine is released, a chemical that controls the brain’s motivation, reward, and pleasure centers, thereby encouraging an organism to repeat a particular behavior. Thus the learned behavior of exchange is reinforced through a chemical pleasure hit. When playing Prisoner’s Dilemma games, the brain scans of the subjects revealed that when they were cooperating, the same areas of the brain were activated as in response to stimuli such as sweets, money, cocaine, and attractive faces. The neurons that were most responsive were those rich in dopamine located in the anteroventral striatum in the “pleasure center” of the brain.56

The effects of trade have been documented in the real world as well as in the lab. In a 2010 study published in Science titled “Markets, Religion, Community Size, and the Evolution of Fairness and Punishment,” the psychologist Joseph Henrich and his colleagues engaged more than two thousand people in fifteen small communities around the world in two-player exchange games in which one subject is given a sum of money equivalent to a day’s pay and is allowed to keep or share some of it, or all of it, with another person. You might think that most people would just keep all the money, but in fact the scientists discovered that people in hunter-gatherer communities shared about 25 percent, while people in societies who regularly engage in trade gave away about 45 percent. Although religion was a modest factor in making people more generous, the strongest predictor was “market integration,” defined as “the percentage of a household’s total calories that were purchased from the market, as opposed to homegrown, hunted, or fished.” Why? Because, the authors conclude, trust and cooperation with strangers lowers transaction costs and generates greater prosperity for all involved, and thus market fairness norms “evolved as part of an overall process of societal evolution to sustain mutually beneficial exchanges in contexts where established social relationships (for example, kin, reciprocity, and status) were insufficient.”57

Trade, Democracy, and Conflict

Instead of configuring the issue of the complex interaction between trade and politics at the global level in terms of categorical binary logic—either you trade or you do not trade, either you are a democracy or you are not a democracy—using a continuous scale reveals more subtle but very real effects. A particular country may trade with other countries very little, some, or a lot, and it may be less or more democratic. This continuous rather than categorical approach enables researchers to treat each case as a datapoint on a continuum rather than as an example or an exception in an artificial choice in which one is tempted to cherry-pick the data to force fit them into preconceived models.

Employing a continuous style of analysis to address this question are the political scientists Bruce Russett and John Oneal in their book Triangulating Peace, in which they use a multiple logistic regression model on data from the Correlates of War Project, which recorded twenty-three hundred militarized interstate disputes between 1816 and 2001.58 Assigning each country a democracy score between 1 and 10 (based on the Polity Project, which measures how competitive its political process is, how openly its leaders are chosen, how many constraints on a leader’s power are in place, the transparency of the democratic process, the fairness of its elections, etc.), Russett and Oneal found that when two countries are fully democratic (that is, they score high on the Polity scale), disputes between them decrease by 50 percent; but when one member of a county pair was either a low-scoring democracy or a full autocracy, it doubled the chance of a quarrel between them.59

When you add a market economy and international trade into the equation it decreases the likelihood of conflict between nations. Russett and Oneal found that for every pair of at-risk nations, when they entered the amount of trade (as a proportion of GDP) they found that countries that depended more on trade in a given year were less likely to have a militarized dispute in the subsequent year, controlling for democracy, power ratio, great power status, and economic growth. In general, the data show that liberal democracies with market economies are more prosperous, more peaceful, and fairer than any other form of governance and economic system. In particular, they found that democratic peace happens only when both members of a pair are democratic, but that trade works when either member of the pair has a market economy.60 In other words, trade was even more important than democracy (although the latter is important for other reasons as well).

Finally, the third vertex of Russett and Oneal’s triangle of peace is membership in the international community, a proxy for transparency. Evil is more likely to thrive in secret. Openness and transparency make it harder for dictators and demagogues to commit violence and genocide. To test this hypothesis, Russett and Oneal counted the number of Intergovernmental Organizations (IGOs) that every pair of nations jointly belonged to and ran a regression analysis with democracy and trade scores, finding that, overall, democracy, trade, and membership in IGOs all favor peace, and that a pair of countries that are in the top tenth of the scale on all three variables are 83 percent less likely than an average pair of countries to have a militarized dispute in a given year.61

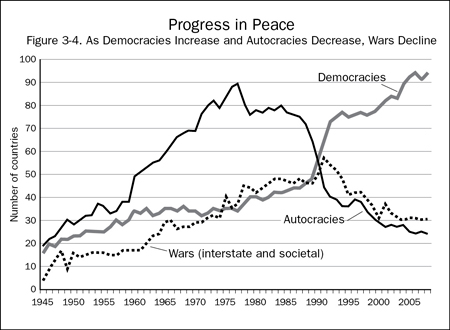

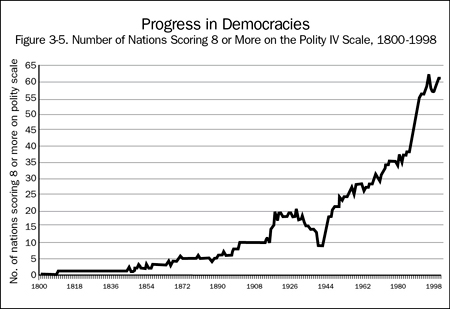

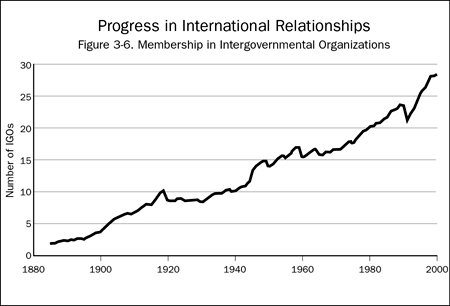

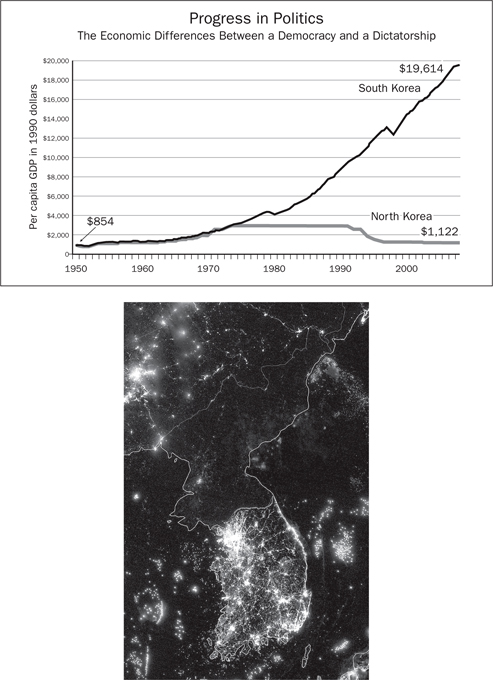

Figure 3-4 presents data showing that as democracies increase and autocracies decrease, war declines.62 Figure 3-5 shows the number of nations scoring 8 or more on the Polity IV scale from 1800 to 2003, revealing a hockey-stick-like improvement in the number of nations after the Second World War who made the transition from autocracies or corrupt democracies to fair and transparent liberal democracies.63 Figure 3-6 shows membership in Intergovernmental Organizations shared by a pair of countries from 1885 to 2000.64 Figure 3-7 brings all these datasets together into a “Trifecta of Peace”: Democracy + Economic Interdependence +Membership in Intergovernmental Organizations = More Peace.

Figure 3-4

Figure 3-5

Figure 3-6

Figure 3-7

Figures 3-4 to 3-7. The Trifecta of Peace: Liberal Democracy, Trade, Transparency.

Figure 3-4 presents data showing that as democracies increase and autocracies decrease, wars decline. Figure 3-5 shows the number of nations scoring 8 or more on the Polity IV scale from 1800 to 2003, showing a hockey-stick-shaped improvement in the number of nations after the Second World War who made the transition from autocracies or corrupt democracies to fair and transparent liberal democracies. Figure 3-6 shows membership in Intergovernmental Organizations shared by a pair of countries from 1885 to 2000. Figure 3-7 brings all these datasets together into a “Trifecta of Peace”: Democracy + Economic Interdependence + Membership in International Organizations = More Peace.

In a 1989 essay on “The Causes of War” Jack Levy noted that the “absence of war between democratic states comes as close as anything we have to an empirical law in international relations.”65 In 2010 Russett and Oneal updated their research and concluded that “the period since World War II has seen progressive realization of the classical-liberal ideal of a security community of trading states.” Since 2010 there has been much conflict around the world, so how has the democratic peace theory held up? In a 2014 special issue of the Journal of Peace Research, the Uppsala University political scientist Håvard Hegre reassessed all of the evidence on “Democracy and Armed Conflict,” concluding “the empirical findings that pairs of democratic states have a lower risk of interstate conflict than other pairs holds up, as does the conclusion that consolidated democracies have less conflict than semi-democracies.”66

* * *

Thinking about the problem of how to reduce conflict between Leviathans in a continuous rather than categorical way also enables us to deal with the apparent exceptions in a more scientific manner because science traffics in continuums and probabilities more than it does in black-and-white categories. For example, when the argument is made that no two democracies ever go to war (the democratic peace theory) or that no two countries who trade with one another ever fight (the McDonald’s peace theory), skeptics reach into the bin of history for the exceptions, such as the United States vs. Great Britain in the War of 1812, the American Civil War, or the India-Pakistan wars—all democracies of a sort—or the great powers on the eve of the First World War, all of whom traded with one another just before the guns of August in 1914. This leads proponents to counter that, say, the United States was not really a democracy because at the time of the War of 1812, and also during the Civil War, slavery was practiced and women couldn’t vote, so it doesn’t count as a true democracy. But treating all historical examples as datapoints on a continuum allows us to perceive nuances in the cause-and-effect relationships at work in the messiness of the real world.

The misreading of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Norman Angell is a case in point. His 1910 book The Great Illusion—in which he argued for the futility of war as a means to greater economic prosperity compared to trade—was pilloried as a fool’s errand in prediction. In 1915, with the Great War ramping up to a full head of steam, the New York Times opined that Angell had “written books in the endeavor to prove that war has been made impossible by modern economic conditions … [but] events have shown their fallacy. Ten nations, more or less closely bound a short time ago by economic ties, are now involved in war.” Nearly a century later, in a 2013 article in the National Interest, Jacob Heilbrunn wrote, “Angell had wrongly deprecated the centrality of power in international relations. In 1914, for example, he announced that ‘There will never be another war between European powers.’”67 And Heilbrunn was defending Angell!

In fact, notes Ali Wyne in a rebuttal in War on the Rocks, what Angell actually said in his pre–World War I edition of the book was that “War is not impossible, and no responsible [p]acifist ever said it was; it is not the likelihood of war which is the illusion, but its benefits.” Angell further clarified his position in a 1913 letter to the Sunday Review (which was included in his 1921 sequel titled The Fruits of Victory) by noting, “not only do I regard war [between Britain and Germany] as possible, but extremely likely.” As Wyne notes, this misreading of Angell blinded subsequent analysts to his additional observations that have relevance to the topic of moral progress: “At least two of them merit reexamination today: ‘national honor’ should not be invoked to justify war, and ‘human nature’ does not make it inevitable.”68 The second observation was especially prescient given what science has learned about the malleability of human behavior, which Angell expressed in his 1935 Peace Prize acceptance speech as clearly as any scientist working today:

Figure 3-8

Figure 3-9

Figure 3-10

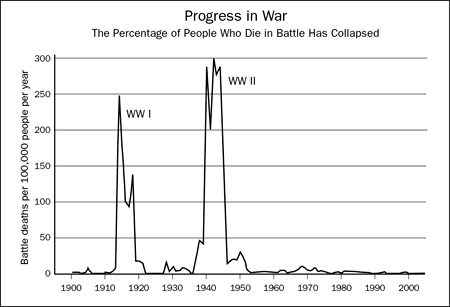

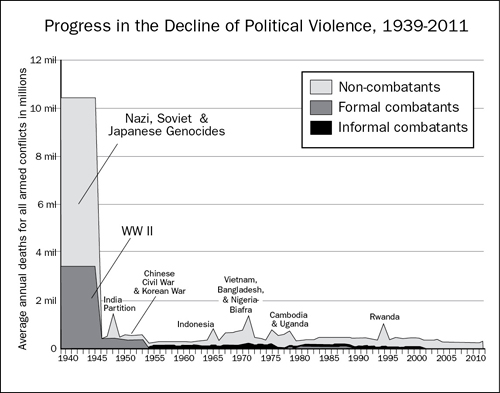

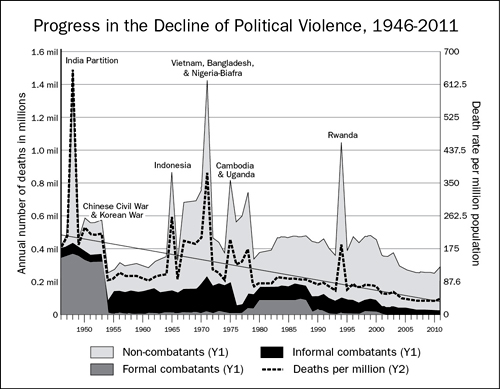

Figures 3-8 to 3-10. Progress in the Decline of War

Figure 3-8 presents data showing the percentage of people who die in battle decreased dramatically in the second half of the twentieth century.70 Figure 3-9 puts that second half century into perspective by tracking the average annual deaths for all armed conflicts in millions, showing how small the spikes are in comparison to the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and the genocides in Cambodia, Uganda, and Rwanda.71 Figure 3-10 expands the death spikes to show the decline even in these wars and genocides between 1946 and 2010.72

Perhaps you cannot “change human nature”—I don’t indeed know what the phrase means. But you can certainly change human behavior, which is what matters, as the whole panorama of history shows.… The more it is true to say that certain impulses, like those of certain forms of nationalism, are destructive, the greater is the obligation to subject them to the direction of conscious intelligence and of social organization.69

Exactly. Whatever your view of human nature—blank slate, genetic determinism, or a realistic nature-nurture interactive model—it is human action that should most concern us when it comes to morality. The way in which people interact with others is what ultimately matters and, when it comes to conflict, at long last we are beginning to understand the conditions under which we can drive war into extinction. Figures 3-8 through 3-10 show just how much progress we have made toward this end.

Leviathans Better and Worse

Hobbes’s Leviathan (or sovereign) required a degree of control over its “subjects” that when put into practice in the twentieth century by various totalitarian regimes failed utterly. Hobbes’s theory fell victim to the tyranny of categorical thinking: either people live in a state of anarchy in a war of all against all, or they give up all their rights and freedoms to a sovereign who controls what people should or should not do. Hobbes proposed, for example, that “every man should say to every man I authorize and give up my right of governing myself to this man, or to this assembly of men, on this condition, that thou give up the right to him, and authorize all his actions in like manner.” This “great Leviathan … may use the strength and means of them all, as he shall think expedient, for their peace and common defence.” The rights and power of this sovereign over the people is almost absolute: subjects cannot change their form of government or transfer their rights to another sovereign. Dissenting minorities must consent to the sovereign and submit to the decrees of the majority “or be left in the condition of war he was before.”

The sovereign is “unpunishable” by his subjects and he is the sole judge in determining the “Peace and Defence” of his subjects, which includes “what opinions and doctrines are averse” to the Commonwealth and thus what may or may not be published. “The sovereignty has the whole power of prescribing the rules whereby every man may know what goods he may enjoy, and what actions he may do, without being molested by any of his fellow subjects; These rules of propriety … and of good, evil, lawful, and unlawful in the actions of subjects are the civil laws.” The sovereign alone decides when and where to wage war, whom it will be waged against, the size of the armies to be deployed, which weapons will be used, and of course the sovereign has the right to tax the subjects to finance the whole operation.

If that’s not extreme enough for our modern Western taste for freedom, Hobbes proposed that the sovereign ought even to control the subjects’ “liberty to buy, and sell, and otherwise contract with one another; to choose their own abode, their own diet, their own trade of life, and institute their children as they themselves think fit, and the like.”73

The problem of giving up so much control and autonomy to a state is that the people running it have the same flaws, biases, prejudices, aspirations, and temptations to cheat as everyone else. The “Hobbesian trap” of the Prisoner’s Dilemma exists in government no less than in business and sports. Granting someone—anyone—too much power leads to the temptation to take advantage and to treat other people like suckers, a temptation that seems to be just too much for most people to resist. An excess of power led to the profound abuses by European monarchs against which the American and French revolutionaries revolted. This is what James Madison had in mind in Federalist Paper Number 51 when he explained why checks and balances between the different branches of government were needed: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.”74 It is what Edmund Burke was thinking when he reflected on the French Revolution: “The restraints on men, as well as their liberties, are to be reckoned among their rights.”75

Democracies developed in response to the monarchic autocracies of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and to the dictatorship regimes of the twentieth century because democracies empower individuals with a methodology instead of an ideology, and it is to this extent that we can see that the scientific values of reason, empiricism, and antiauthoritarianism are not the products of liberal democracy but the producers of it. Democratic elections are analogous to scientific experiments: every couple of years you carefully alter the variables with an election and observe the results. If you want different results, change the variables.76 The political system in the United States is often called the “American experiment,” and the founding patriarchs referred to it as such, and thought of this experiment in democracy as a means to an end, not an end in itself.

Many of the Founding Fathers were, in fact, scientists who deliberately adapted the method of data gathering, hypothesis testing, and theory formation to their nation building. Their understanding of the provisional nature of findings led them to develop a social system in which doubt and dispute were the centerpieces of a functional polity. Jefferson, Franklin, Paine, and the others thought of social governance as a problem to be solved rather than as power to be grabbed. They thought of democracy in the same way that they thought of science—as a method, not an ideology. They argued, in essence, that no one knows how to govern a nation, so we have to set up a system that allows for experimentation. Try this. Try that. Check the results. Repeat. That is the very heart of science. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1804, “No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth.” However, he noted, as in science, where open peer criticism and the freedom to debate increase the probability of discovering provisional truths, Jefferson added that this daring new political experiment being tried in the New World depended unconditionally on open access to knowledge and the freedom of its citizens to see and to think for themselves: “Our first object should therefore be, to leave open to him all the avenues to truth. The most effectual hitherto found, is the freedom of the press. It is therefore, the first shut up by those who fear the investigation of their actions.”77

Even the fundamental principles underlying the Declaration of Independence, which is usually thought of as a statement of political philosophy, were in fact grounded in the type of scientific reasoning that Jefferson and Franklin employed in all the other sciences in which they worked. Consider the foundational line, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.…” In his biography of Benjamin Franklin, Walter Isaacson recounts the story of how the term “self-evident” came to be added to Jefferson’s original draft by Franklin, on Friday, June 21, 1776.

The most important of his edits was small but resounding. He crossed out, using heavy backslashes that he often employed, the last three words of Jefferson’s phrase, “We hold these truths to be sacred and undeniable” and changed them to the words now enshrined in history: “We hold these truths to be self-evident.”

The idea of “self-evident” truths was one that drew less on John Locke, who was Jefferson’s favored philosopher, than on the scientific determinism espoused by Isaac Newton and on the analytic empiricism of Franklin’s close friend David Hume. In what became known as “Hume’s fork,” the great Scottish philosopher, along with Leibniz and others, had developed a theory that distinguished between synthetic truths that describe matters of fact (such as “London is bigger than Philadelphia”) and analytic truths that are self-evident by virtue of reason and definition (“The angles of a triangle equal 180 degrees”; “All bachelors are unmarried.”) By using the word “sacred,” Jefferson had asserted, intentionally or not, that the principle in question—the equality of men and their endowment by their creator with inalienable rights—was an assertion of religion. Franklin’s edit turned it instead into an assertion of rationality.78

The hypothesis that reason-based Enlightenment thinking leads to moral progress is one that can be tested through historical comparison and by examining what happens to countries that hold anti-Enlightenment values. Countries that quash free inquiry, distrust reason, and practice pseudoscience, such as Revolutionary France, Nazi Germany, Stalinist Russia, Maoist China, and, more recently, fundamentalist Islamist states, stagnate, regress, and often collapse. Theists and postmodernist critics of science and reason often label the disastrous Soviet and Nazi utopias as “scientific,” but their science was a thin patina covering a deep layer of counter-Enlightenment, pastoral, paradisiacal fantasies of racial ideology grounded in ethnicity and geography, as documented in Claudia Koonz’s book The Nazi Conscience79 and in Ben Kiernan’s book Blood and Soil.80