Chapter One

Psychosynthesis Personality Theory

This conception of the structure of our being offers us a wider and more comprehensive understanding of the human drama, and points the way to our liberation.

—Roberto Assagioli

In 1910, a young psychiatrist-in-training named Roberto Assagioli (1888–1974) conceived of a psychology he called psychosynthesis. By “psycho-synthesis” he meant to denote the realization of wholeness or synthesis both within oneself and with the world—a counterpoint to Sigmund Freud's “psycho-analysis” that implied the analysis of the person into component parts.

Assagioli had been quite active in early psychoanalytic circles, so much so that C. G. Jung had written to Freud about him as “our first Italian” (McGuire 1974, 241). However, Freud (1948) felt strongly that “psycho-synthesis” occurred automatically as analysis proceeded, so for him there was no need to focus on synthesis per se.

For Assagioli on the other hand, synthesis was fundamental to human nature; it was an intrinsic impulse toward integration, wholeness, and actualization and deserving of study in its own right. While accepting the need for analytic exploration of the personality, Assagioli sought to understand the movement of synthesis as it occurs within the individual, among couples and groups (inter-individual psychosynthesis), and in the world at large. He understood synthesis as a powerful evolution toward “union, beauty, and harmony” that arose from “links of love” among individualities (Assagioli 2000, 27).

Assagioli subsequently developed psychosynthesis as a broad point of view, a way of looking at human beings from the standpoint of this evolution toward integration, relationship, and wholeness. As he wrote, psychosynthesis is “first and foremost a dynamic, even a dramatic conception of our psychological life” (Assagioli 2000, 26). Psychosynthesis is thus not a particular technique or method, but a context for technique and method; nor is it a psychotherapy, but a way of practicing psychotherapy; nor is it a spiritual path, but a perspective on the experiential terrain of spiritual paths.

This chapter presents a personality theory that recognizes the workings of this impulse toward synthesis at the very core of the human being, while the next chapter traces this impulse as it forms the axis of growth over the human life span. The remainder of the book is then devoted to a psychosynthesis clinical approach that can be called psychosynthesis therapy. Here the nurture of this impulse toward synthesis is seen as empathic love, and thus the therapeutic task and the role of the therapist is essentially about synthesis, relationship, and love.

ASSAGIOLI'S MODEL OF THE PERSON

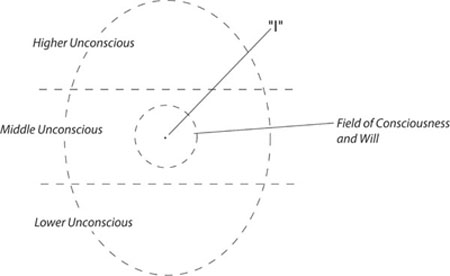

The earliest and most widely known psychosynthesis model of the human personality is Assagioli's oval-shaped or “egg” diagram illustrating what he called “a pluridimensional conception of the human personality” (Assagioli 2000, 14). This model was first published in the 1930s (Assagioli 1931; 1934), later becoming the lead chapter in his book Psychosynthesis (2000), and it remains an integral and vital part of psychosynthesis theory to this day.1

Mindful of Assagioli's statement that this model was “far from perfect or final” (Assagioli 2000, 14), we here present his model with one change: we do not represent Self (or Transpersonal Self) on the diagram. While Assagioli's original diagram depicted Self at the apex of the higher unconscious, half inside and half outside the oval, the diagram that follows does not do so; in this rendering, Self is not assigned to any one particular sphere at all, and instead should be imagined as pervading all the areas of the diagram and beyond. The need for this change will be discussed later. Figure 1.1 is then a rendering of Assagioli's diagram with this one modification.

One general comment about this diagram is that Assagioli understood the oval to be surrounded by what C. G. Jung termed the collective unconscious (unlabeled) or “a common psychic substrate of a suprapersonal nature which is present in every one of us” (Jung 1969, 4). This realm surrounds and underpins the personal levels of the unconscious and represents innate propensities or capacities for particular forms of experience and action shared by the species and developed over the course of evolution. Let us now describe each element in the diagram in turn.

THE MIDDLE UNCONSCIOUS

The middle unconscious … is formed of psychological elements similar to those of our waking consciousness and easily accessible to it. In this inner region our various experiences are assimilated, our ordinary mental and imaginative activities are elaborated and developed in a sort of psychological gestation before their birth into the light of consciousness. (Assagioli 2000, 15)

FIGURE 1.1

The middle unconscious is depicted in the oval diagram as immediately surrounding the field of consciousness and will. This is meant to symbolize that this area of the unconscious immediately underpins our ongoing daily awareness and behavior. The middle unconscious is not a repressed area of the personality dissociated from awareness, but rather an unconscious area that is in direct association with awareness. The field of neuroscience has used the term “nonconscious” with much the same meaning:

Huge amounts of evidence support the view that the “conscious self” is in fact a very small portion of the mind's activity. Perception, abstract cognition, emotional processes, memory, and social interaction all appear to proceed to a great extent without the involvement of consciousness. Most of the mind is nonconscious. These “out-of-awareness” processes do not appear to be in opposition to consciousness or to anything else; they create the foundation for the mind in social interactions, internal processing, and even conscious awareness itself. Nonconscious processing influences our behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. Nonconscious processes impinge on our conscious minds: we experience sudden intrusions of elaborated thought processes (as in “Aha!” experiences) or emotional reactions (as in crying before we are aware that we are experiencing a sense of sadness). (Siegel 1999, 263)

The phrase, “sudden intrusions of elaborated thought processes (as in ‘Aha!’ experiences),” echoes Assagioli's statement quoted earlier, “mental and imaginative activities are elaborated and developed in a sort of psychological gestation before their birth into the light of consciousness.” Here is a level of the unconscious that is not in opposition to consciousness, but which contains the complex processes and structures from which we operate in our daily lives. It is in direct association with consciousness and supports conscious functioning in a number of ways.

STRUCTURALIZATION OF THE MIDDLE UNCONSCIOUS

One way the middle unconscious supports consciousness and will is that we here assimilate our unfolding inherited endowment and our interactions with the environment to form patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior by which we express ourselves in the world. Assagioli affirms the neurobiology involved in this process, referring to it as developing “new neuromuscular patterns”:

This process is apparent in the work of acquiring some such technical accomplishment as learning to play a musical instrument. At first, full attention and conscious direction of the execution are demanded. Then, little by little, there comes the formation of what might be called the mechanisms of action, i.e., new neuromuscular patterns. The pianist, for example, now reaches the point at which he no longer needs to pay conscious attention to the mechanics of execution, that is, to directing his fingers to the desired places. He can now give his whole conscious attention to the quality of the execution, to the expression of the emotional and aesthetic content of the music that he is performing. (Assagioli 1973b, 191)

Assagioli's “neuromuscular patterns” would in today's neuroscience be understood as neurons firing together and so becoming organized into neural networks: “In a process called long-term potentiation (LTP), excitation between cells is prolonged, allowing them to become synchronized in their firing patterns and organized into neural networks (Hebb 1949)” (Cozolino 2006, 42). These neural networks can then interconnect, “allowing for the evolution and development of increasingly complex skills, abilities, and abstract functions” (42).

Whether learning to walk, talk, or play an instrument; developing roles within family and society; or forming particular philosophical or religious beliefs, we create these complex expressions by synthesizing our innate gifts and environmental experience into a larger whole. In this way, areas of what Assagioli (1973b; 2000) so aptly and so early called the “plastic unconscious” become structuralized into what he called the “structuralized” or “conditioned” unconscious.2 Perhaps one of the most complex expressions of this structuralization is the formation of what Assagioli called subpersonalities (Assagioli 2000).

SUBPERSONALITIES

Among the most sophisticated of the integrated patterns structuralizing the middle unconscious are subpersonalities. Subpersonalities are like some of the “atoms” that make up the “molecule” of the personality, or the “organs” that make up the “body” of the personality.

Subpersonalities are patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior, developed in relationship to various environments, that have advanced to the level at which they can operate as distinct, semi-independent entities. In neuroscience terms, these are discrete neural networks functioning as “specialized selves” or “self-states” in which “various modules of the mind cluster together in the service of specialized activity” (Siegel 1999, 230). Psychiatrist and author Daniel Stern sums up the current state of thinking on these “multiple selves”: “It is now largely accepted that there are multiple (context-specific) selves that can interact with each other, observe each other, and converse together out of consciousness. This is normal, not limited to pathological dissociative states” (Stern 2004, 128).

Awareness of subpersonalities may occur, for example, in noticing trains of thought “speaking” inwardly (“You really did well,” “You shouldn't do that”), or in characteristic attitudes that arise in some situations and not others (“Being with you brings out my playful side,” “When I'm with my father I feel like a child again”), or perhaps in feeling a strong, discrete impulse to a specific type of behavior (“Whenever I'm around an authority figure, I want to rebel,” “On a day like this I really want to be outdoors”). Often too, in therapy especially, subpersonalities emerge in inner conflicts: “I have a part of me who wants to do it and another who is afraid,” or, “I feel ambivalent—part of me likes it and another hates it.”

In carefully exploring all such experiences, we can discover that these are not simply passing thoughts and feelings, but expressions of discrete complexes characterized by a specific motivation and mode of expression, a consistent worldview and range of feelings, and a particular life history with roots in our personal history.

Most often subpersonalities do not emerge into awareness because in normal functioning they are working together seamlessly in the middle unconscious. But if there is a conflict among them—as between a fearful child and harsh critic, or a hard worker and a fun-lover, or a solitude seeker and a social extravert—one will quickly become aware of the inner turmoil this conflict will produce.

In cases of inner conflict, it can be quite worthwhile to work with the conflicting parts in an intentional, conscious way, bringing empathic love to them. We have described subpersonality work in detail elsewhere (Firman and Gila 1997; 2002). This type of work has been a strong component of psychosynthesis therapy since the 1970s (Carter-Haar 1975; Vargiu 1974), and more recently has been addressed by other approaches as well (Polster 1995; Rowan 1990; Schwartz 1995; Sliker 1992; Stone and Winkelman 1985; Watkins and Watkins 1997).

So subpersonalities are quite the norm even in psychologically healthy people, and while their conflicts can be the source of pain and even psychological symptoms, they themselves should not be seen as pathological. They are simply discrete patterns of feeling, thought, and behavior that often operate out of awareness—in the middle unconscious—and that form the “colors” of the “palette” from which we paint our life. They may also have roots in the higher and lower unconscious, and in the archetypes of the collective unconscious (Firman and Gila 2002; Meriam 1994).

UNCONSCIOUS STRUCTURALIZATION OF SELF AND WORLD

Although the middle unconscious can receive patterns that are consciously formed, it can also be structured without the intercession of consciousness at all (this holds for subpersonality formation as well). Such unconscious learning is a function of what neuroscience calls “implicit memory” (Cozolino 2002; Lewis, Amini, and Lannon 2001; Siegel 1999; Stern 2004). This structuralization of the middle unconscious allows us, for example, to learn all the many complex rules of grammar without ever being conscious of these rules; that is, when we hear proper grammar we simply know it “sounds right,” remaining unaware of the complex learning that underpins that knowing. In fact, this structuralization begins before we are born:

Bathed for nine months in his mother's vocalizations, a baby's brain begins to decode and store them—not just the speaker's tone, but her language patterns. Once born, a baby orients to the familiar sounds of his mother's voice and her mother tongue, and favors them over any other. In doing so, he demonstrates the nascent traces of both attachment and memory. (Lewis, Amini, and Lannon 2001, 112)

This unconscious structuralization allows us to automatically and quickly respond to the environment based on past experience, bypassing the slower, more deliberate, or unavailable response moderated by consciousness. We here form patterns based on our experience of ourselves in relationship to our world, unconsciously learning ways of being and acting from interaction with different environments. This adaptive structuralization of the middle unconscious can be seen in the concept of the “adaptive unconscious” (Wilson 2002).

Unconscious structuralization is not then experienced as consciously recalling something that has happened in the past. Instead, it is experienced simply as “the way things are,” as “reality.” We have, through our connections with the environment, built up an inner map of the world and of ourselves by which we live our lives for better or worse (see the discussion of internal unifying centers in chapter 2). So our experience of self and world is profoundly conditioned by the structuralization of the middle unconscious. Siegel writes of implicit memory, “We act, feel, and imagine without recognition of the influence of past experience on our present reality” (Siegel 1999, 29).

This understanding of the middle unconscious becomes crucial for psychosynthesis therapy because it is into this world of the client that empathic love takes the therapist. Therapists seeking to attune to their client's world need to be prepared to enter an idiosyncratic, unpredictable world perhaps starkly different from their own.

Furthermore, the therapist must realize that since this inner landscape was gradually built up via early relationships with others, it is only the therapist's presence and resonance in the relationship that can allow transformation of that landscape. For example, a therapist cannot simply talk the client out of a negative self-image, but must be prepared to be with the client in an exploration of a world experienced from this negative self-image. In the parlance of neuroscience, “When a limbic connection has established a neural pattern, it takes a limbic connection to revise it” (Lewis, Amini, and Lannon 2001, 177).

Conscious technique, assigned exercises, interpretations, insight, or the surfacing of memories does not, then, facilitate healing and growth at this level; rather, healing and growth can only come by empathically joining clients in the unique world of their middle unconscious. This will be discussed more fully in the presentation of clinical theory next.

THE EXPERIENTIAL RANGE

This inner structuring of self and world in relationship to significant others—this formation of the middle unconscious—also forms the normal range of our potentially conscious experience. That is, it demarcates those types of experience that are easily accessible to our normal awareness, that range of experience we recognize as a part of our lived reality. In neuroscience, this range of experience is akin to what is termed the “window of tolerance,” that is, the range that constitutes a person's experiential comfort zone (Siegel 1999).

Life experiences that we have successfully integrated into the middle unconscious allow us to be more ready and able to engage these same types of experience when we encounter them again. If we have integrated various experiences of, for example, joy and wonder, anger and fear, success and failure, or loss and grief, we will be able to feel and express these experiences as life brings them to us. Gradually all of these integrations together begin to form the range of experience to which we are normally available on a daily basis—in other words, our experiential range is developing. Experiences along this range are by definition not foreign and disturbing to us, nor threatening or overwhelming to our sense of self, but are experiences—pleasant or unpleasant—that we know how to engage as a part of life.

This structuralization of the middle unconscious is thus like developing experiential “eyes,” an organ of consciousness, through which we perceive and act in the world. It is not that we are operating along this entire range at all times, but that we are sensitive and responsive along this entire spectrum as we meet life events; we are aware when we are loving or grieving, happy or sad, joyous or scared, tense or relaxed, unitive or isolated, and can by the same token be empathic with others who are having these experiences.

Over time, then, we engage and integrate our life experiences such that our experiential range develops. We find ourselves able to be conscious of, and respond to, all the various aspects of human experience that present themselves to us. On the other hand, as we shall now see, relating to nonempathic environments leaves us with an experiential range that is constricted and broken.

PRIMAL WOUNDING

The middle unconscious allows learned patterns of perception and action (consciously learned or not) to remain unconscious so that we may creatively draw upon these patterns in the living of our lives. By remaining unconscious yet available, the middle unconscious supports our ongoing functioning.

However there are other layers of the unconscious that are not simply and naturally unconscious, but are actively repressed. That is, these are sectors of the unconscious that support ongoing functioning by remaining unconscious and not accessible. But why should one find it necessary to cut off and disown areas of natural human experience? This is done in response to what can be called primal wounding (Firman and Gila 1997; 2002):

Primal wounding results from violations of the person's sense of self, as seen most vividly in physical mistreatment, sexual molestation, and emotional battering. Wounding may also occur from intentional or unintentional neglect by those in the environment, as in physical or emotional abandonment; or from an inability of significant others to respond empathically to the person (or to aspects of the person); or from a general unresponsiveness in the surrounding social milieu. … All such wounding involves a breaking of the empathic relationships by which we know ourselves as human beings; it creates an experience in which we know ourselves not as intrinsically valuable human persons, but instead as non-persons or objects. In these moments we feel ourselves to be “It”s rather than “Thou”s, to use Martin Buber's (1958) terms. Primal wounding thus produces various experiences associated with facing our own potential non-existence or nonbeing: isolation and abandonment, disintegration and loss of identity, humiliation and low self-worth, toxic shame and guilt, feelings of being overwhelmed and trapped, or anxiety and depression/despair. (Firman and Gila 2002, 27)

In order to avoid this personal annihilation, we will disown those areas of experience deemed unacceptable by the environment. By eliminating these ranges of experience from ongoing functioning, we form a personality that allows us to survive in the nonempathic environment.3 But what then is the nature of these disowned aspects of ourselves, these dissociated neural networks, these lost levels of our experiential range?

THE HIGHER AND LOWER UNCONSCIOUS

The first thing that must be disowned in order to survive within a nonempathic environment is the fact that we are being wounded at all. Our wounding will not receive an empathic ear in such an environment because for the environment to accept our wounding it would need to acknowledge its role in this wounding and begin its own process of self-examination, healing, and growth. (Good-enough parenting, like good-enough friendship and good-enough psychotherapy, seeks to acknowledge empathic failures past and present so the wounding can be held.)

In order to survive in a nonempathic environment, we develop a personality that eliminates primal wounding from our awareness (what is called survival personality in the next chapter). We enter a trance that in effect breaks off our awareness of wounding and any experiences associated with annihilation and nonbeing, forming what is called the lower unconscious (see Figure 1.1).

The lower unconscious is then the disowned range of our experience that would normally attune us to experiences most directly related to the pain of primal wounding—experiences such as anxiety and disintegration; lack of meaning in self or world; feeling lost, trapped, or buried; isolation, abandonment, banishment; feeling overwhelmed, helpless, or hopeless; emptiness or hollowness; despair, shame, and guilt (see chapter 2). Under the threat of personal annihilation, significant sectors of our ability to experience pain and suffering are here split off from ongoing awareness.

HIDING THE GIFTS

But there is something else that cannot be held by the nonempathic environment and thus must be disowned so as to survive in that environment: those positive aspects of ourselves, those authentic gifts, that are unseen and rejected by the nonempathic environment. These gifts are in effect under attack within the environment, and their possession places us under constant threat of annihilation.

As with the wounding experiences, these gifts must be hidden in what psychosynthesis psychotherapist Frank Haronian (1974) wrote about as the “repression of the sublime.” So we do much the same here. We break off that range of our experience related to whatever positive qualities of being are threatened by the environment—qualities that might include beauty, compassion, courage, creativity, wonder, humor, joy, bliss, light, love, patience, truth, faith, and wisdom.4

Such qualities, termed transpersonal qualities in psychosynthesis, are characteristic of the higher unconscious (Figure 1.1). These are the types of qualities that are eliminated from our experiential range, rendering us safe in the nonempathic environment, but also leaving us with an impoverished sense of ourselves and the world.

SPLITTING AND REPRESSION

So in primal wounding, if there is not an alternative environment that can hold the person in both gifts and wounding (in empathic love), these two very opposed types of experience—experiences of the delight in being and the terror of nonbeing—cannot be held as a whole, cannot be synthesized. They are therefore in effect broken away from each other and banished from the experiential world of the middle unconscious.

Another way to say this is that the gifts and wounds have been split and then repressed, forming the higher and lower unconscious. One then lives in a truncated middle unconscious world, overarched by the “paradise” of the higher unconscious and underpinned by the “netherworld” of the lower unconscious. Such splitting of “good” and “bad” has long been recognized in psychoanalytic circles (Fairbairn 1986; Kernberg 1992; Klein 1975; Masterson 1981).5

In splitting and repression of these levels of experience we disown the heights and depths of ourselves deemed unacceptable by the nonempathic environment. Note that the unacceptable ranges are not here simply unrecognized by the environment, as, for example, when caregivers may not share the heights or depths of experience available to the child; here these areas of experience would remain available to the child and could be easily nurtured by relationships with others. Rather, splitting and repression occur only when a particular range of experience represents an emotional or mental threat to the caregivers—a result of their own wounding. In this case, the child engaging these levels of experience faces not mere puzzlement and curiosity from caregivers, but active rage, shame, and emotional abandonment.

In the following chapter we shall further explore the nature of primal wounding, but let us now return to Assagioli's model of the person and examine “I,” the mysterious “who” to whom all of these levels of the unconscious belong.

“I” OR PERSONAL SELF

“I” or personal self (with a lowercase “s”), with the attendant field of consciousness and will, is pictured at the very center of the oval-shaped diagram (Figure 1.1). “I” could also be called “you.” When you are loved beyond the content and process of your personality, you emerge; you are the one who can experience all these different inner and outer realms, can make choices about these experiences, and can blend them into meaningful expressions in the world.6

But the nature of “I” is profoundly mysterious and by no means self-evident. As Assagioli points out, “the self, the I-consciousness, devoid of any content … does not arise spontaneously but is the result of a definite inner experimentation” (Assagioli 2000, 99). “I” needs to be pointed to, understood, and loved; you need to be invited out from among the content and process of your personality. And a psychology of love would have an understanding and a method for seeking, knowing, and loving you in this way. Here is Assagioli offering one way:

The procedure for achieving self-identity, in the sense of the pure self-consciousness at the personal level, is an indirect one. The self is there all the time; what is lacking is a direct awareness of its presence. Therefore, the technique consists in eliminating all the partial self-identifications. The procedure can be summarized in one word which was much used formerly in psychology but which recently has been more or less neglected, i.e., introspection. It means, as its terminology clearly indicates, directing the mind's eye, or the observing function, upon the world of psychological facts, of psychological events, of which we can be aware. (Assagioli 2000, 101)

He further suggests that such a sustained introspection (an aspect of meditation or contemplation in spiritual traditions) focus on three levels of experience: physical sensations, feelings, and thoughts. He writes of this method, “This objective observation produces naturally, spontaneously and inevitably a sense of dis-identification from any and all of those psychological contents and activities. By contrast, the stability, the permanency of the observer is realized” (103). The reader is invited to perform this inner experimentation as we go.7

A DISIDENTIFICATION EXERCISE

Assagioli first invites you to observe the ever-changing flow of your physical sensations: the fluctuations of temperature within your body, the passing experiences of constriction or relaxation, changes in breathing, the parade of tastes and smells. To each and all of these changing sensations you can be present, ergo, you are distinct but not separate from your sensations. Otherwise you would be unable to be fully present to each new sensation as it arises. This phenomenon can be called transcendence-immanence (Firman 1991; Firman and Gila 1997; 2002). Something about who you are is distinct from—transcendent of—sensations, yet you are engaged with—immanent within—sensations. You are transcendent-immanent with respect to sensations.

Assagioli next suggests becoming aware of “the kaleidoscopic realm of emotions and feelings” (102). Here you will notice the constant flow of different emotions: sadness, joy, grief, calm, arousal, happiness, despair, hope. But here again, since you can engage each and every one of these, remaining present to each successive feeling, you must be somehow transcendent-immanent with respect to feelings too. Or in Assagioli's words, “After a certain period of practice we come to the realization that the emotions and feelings also are not a necessary part of the self, of our self, because they too are changeable, mutable, fleeting and sometimes show ambivalence” (102).

Lastly, Assagioli invites you to become conscious of your thoughts in the same way: “mental activity is too varied, fleeting, changeable; sometimes it shows no continuity and can be compared with a restless ape, jumping from branch to branch. But the very fact that the self can observe, take notice and exercise its powers of observation on the mental activity proves the difference between the self and the mind” (102). In our terms, “I” is distinct-but-not-separate from, transcendent-immanent with respect to, the thinking process as well.

In this type of inner exploration, you can begin to plumb the mysterious nature of “I,” of you. Again, this nature is not self-evident and is realized only as you are held in empathic love. You must be seen, known, and loved as distinct-but-not-separate from your experience, and so free to be open to whatever arises in you—an invitation to authenticity directly opposed to the truncated experiential range conditioned by the need to survive in a nonempathic environment.

In other words, you can discover you are “in but not of the world” of soma and psyche, of body and mind, distinct from both yet engaged in both. You can begin to realize that you are transcendent-immanent of any and all experiences you may encounter, that you can remain present and volitional within all experiences that life can bring you.

So it seems accurate to refer to human being as transcendent-immanent spirit. This use of the word “spirit” is helpful if it is understood that this does not refer to another “thing” among “things,” nor a substance or object within us, nor a tiny homunculus living within the psyche-soma, but rather refers to our ability to remain distinct-but-not-separate or transcendent-immanent of any and all experiences of psyche and soma.

“YOU” ARE NOT AN EXPERIENCE

Furthermore, disidentification from contents and forms of experience can extend to deeper and more pervasive structures of the personality as well. These might include such things as subpersonalities, complexes, habitual feeling states, and even lifelong images and beliefs about who you are—all things that tend to become confused with “I,” things with which “I” can become identified. (Disidentification at these more ingrained levels may involve psychological work in order to uncover and address the wounds underlying the identifications.)

Pursued at depth, this disidentification means “I” is transcendent of any experience that “I exist” at all! Disidentifying from any notion of “I,” “me,” or “self,” we will discover that even the “who” we secretly thought we were behind all the identifications is not even us. Assagioli writes, “the last and perhaps most obstinate identification is with that which we consider to be our inner person, that which persists more or less during all the various roles we play” (107).

So note that “I” is not another experience among others. “I” is the experiencer, never the experience. Even though a particular moment of disidentification may produce an experience of “I don't exist” and “noself,” of freedom and spaciousness, of peace and stillness, of clear light and pure consciousness, of witnessing and observing, these remain experiences that “I” may or may not have.8

In fact, it is quite common that disidentification leads not to serene observation but to chaotic and confusing experiences. This can be seen, for example, in what we call a crisis of transformation (chapter 7) when one disidentifies from a long-standing identity and is unsettled by the sensations, feelings, and thoughts that had been repressed by the identification.

But throughout all changing experience, you are you—“I”—whether identified or disidentified, peaceful or chaotic, centered or off center. Looked at more closely, it can be seen that you not only have the ability to remain present to, and conscious of, ongoing experience, but can be active in affecting these ongoing experiences as well. That is, “I” has not only consciousness but also will.

CONSCIOUSNESS AND WILL

One of the two functions of “I” according to Assagioli is consciousness. This notion is based on the observation that in disidentification from limiting structures of experience, your consciousness becomes free to engage a much wider experiential range. That is, when you are identified with a single part of yourself, your consciousness is controlled by that identification, almost as if you look out at the world through that single “lens.” If you are identified with the parent part of yourself, for example, you will experience the world as a parent and be out of touch with perhaps the hurt or playful child in you, the fun-loving adolescent within, or the spontaneous artistic side of yourself. Here you may relate to your adult children (and other people) as if they were children or teenagers, and be unable to bring other parts of yourself into the relationship.

In disidentification from such a role, however, your consciousness is free to engage these other parts of yourself; you become open to the full richness of your inner community, and can experience the world unshackled by the blinders of a single identification. Here it is clear that consciousness partakes of transcendence-immanence: it can be free to engage any and all experiences, any and all parts of ourselves. So as “I” disidentifies, the consciousness of “I” becomes free, and you find that an essential fact about who you are seems to be: “I have awareness (or consciousness).”

Another thing that occurs in disidentification is that you become increasingly free to make a variety of different choices—this points to the second function of “I,” will. Trapped in a particular identification, you can only make choices from within the perspective of that single part of you. If you are trapped in a constricted people-pleasing role, for example, you will only make choices that are pleasing to others, and will perhaps have difficulty making choices to be candid, spontaneous, or self-assertive. In disidentification, however, you find you can make choices from beyond any single identification, that you can make choices from the full range of who you are, drawing on the complete “palette” of your rich human potential.

As with consciousness, you find that your will, your ability to affect the contents and structures of consciousness, is freed in stepping out of any limited identification with a single part of yourself. As Assagioli wrote, “Then the observer becomes aware that he can not only passively observe but also influence in various degrees the spontaneous flow, the succession of the various psychological states” (103).

Will too is then transcendent-immanent, potentially able to affect all the various passing contents of experience without being dominated by any. So a second important fact about who you are seems to be: “I have will.” Therefore “I” in the oval diagram is seen as surrounded by the field of consciousness and will, representing these two most intimate functions of our essential selves.

But be careful here too not to equate the functions of consciousness and will with the experiences of being conscious and willing. These functions of “I” may be completely obscured if you are identified with, for example, a strong part of you that fills your consciousness and dominates your will. Again, you are still “you” in this state of identification; you still have the functions of consciousness and will, even though your consciousness and will are presently submerged within, in a sense possessed by, the identification.

EMPATHIC LOVE

As you proceed over time with this type of inner observation, you can find that since you are not any particular experience, you can embrace any and all experiences as they arise. These experiences can include moments of ecstasy, creative inspiration, and spiritual insight (higher unconscious); feelings of anxiety, despair, and rage (lower unconscious); as well as ongoing engagement with various patterns of thought, feeling, and behavior that you have formed over the course of living (middle unconscious). By virtue of your transcendence-immanence, it would seem there is no experience you cannot embrace. In the words of one early psychosynthesis writer: “There are no elements of the personality which are of a quality incompatible with the ‘I.’ For the ‘I’ is not of the personality, rather it transcends the personality” (Carter-Haar 1975, 81).

You discover, in other words, that you are fundamentally empathic and loving toward all aspects of your personality. You can love, accept, and include a vast range of experience, take responsibility for the healing and growth of this range, and even over time form these experiences into a rich, cohesive expression in the world. You have the ability to have “selfless love” or “agape” toward all of your personality aspects—not taking sides with any, understanding and respecting all, embracing all. The tremendous healing and growth of one's personality from this emergence of empathic love—from the emergence of “I”—are common occurrences in psychosynthesis practice; indeed, this is at the heart of psychosynthesis therapy in general. As Assagioli affirms, “I am a living, loving, willing self” (Assagioli 1973b, 176).

Note that “I” does not imply the experience of oneself as some sort of rugged, separate individual as is often the ideal implicit in much of Western culture. The emergence of “I” (see chapter 9) can manifest in as many different ways as there are cultures. You may experience yourself as a free and independent agent in relationship to the wider society or, quite the contrary, as not an “individual” at all but rather an expression of your ancestry, family, and community. However it is that you do experience yourself, you have the ability to understand and act from within the subjectivity of your own body, feelings, and mind.

Finally, in order to complete our discussion of psychosynthesis personality theory, let us consider the source of this loving, empathic, transcendent-immanent, willing, and conscious spirit—to wit, loving, empathic, transcendent-immanent, willing, and conscious Spirit, or Self.

SELF

For Assagioli's contemporaries Freud and Jung the ego was a composite or complex of various psychological elements that formed over the course of development. Whereas a Freudian or Jungian might, for example, consider ego arising from a gradual differentiation of the “id” or a de-integrate of the “self,” respectively, Assagioli held that “I” was a direct “reflection” or “projection” of deeper, transpersonal, or higher Self.9

Thus, in pondering the nature of Self, we can begin with an examination of Self's reflection or image: we can return to our insight into the nature of human spirit, of “I.” Since “I” is not “ego,” not an organization of content within the personality, we cannot logically posit a source that is composed of content, even a totality of all content. If “I” is loving, empathic, transcendent-immanent spirit, it would rather seem that the source of “I” must be a greater or deeper loving, empathic, transcendent-immanent Spirit (capital “S”).

Thus we may assume logically that Self is simply a more profound empathic transcendence-immanence than “I.” Just as “I” is distinct-but-not-separate from the flow of immediate experience, so Self can be thought of as distinct-but-not-separate from any and all content and layers of the personality, both conscious and unconscious. Self is transcendent and so may be immanent anywhere, any time, within the entire personality and beyond.

Practically what this means is that we are held in being no matter what type of experiences we might have. Our life-giving connection with Self is not intrinsically about any particular experience or state of consciousness but holds us in being so that we may engage experiences throughout our entire experiential range.

A loving empathic transcendent-immanent Self can therefore be thought of as present and potentially active whether one is experiencing a traumatic memory from the lower unconscious, a peak experience in the higher unconscious, working with middle unconscious patterns, engaging existential issues of mortality and meaning, or expressing oneself in the world. As the direct and immediate source of “I,” Self is always potentially available to us for dialogue, support, and guidance no matter what our experience, no matter what our stage of development, no matter what our life situation.

This profound transcendence-immanence of Self is a reason we have not followed Assagioli in representing Self at the apex of the higher unconscious. We believe that his earlier rendering of Self on the oval diagram can lead to the mistaken assumption that Self somehow belongs to “higher realms” and is not as directly present to the “lower realms.”10

The notion of Self as more deeply or more broadly transcendent-immanent also allows us to recognize the vast array of forms through which Self can express—from individuals and groups, to spiritual practices and religious forms, to the natural world, to inner psychological structures. How might one describe the empathic, loving, holding power that is manifest through all such contexts, both inner and outer, animate and inanimate, to empower empathic, loving, transcendent-immanent “I”? It would have to be some empathic presence that can express in all of these contexts yet be identified with none, a transcendent-immanent Source operating through different forms both inner and outer. The notion of loving, empathic, spiritual, transcendent-immanent Self seems quite useful in this regard.

Just as in the discussion of human spirit or “I,” however, we should be clear that by “Self” or “Spirit” we are not positing a particular “thing” among “things.” Self is not an object of consciousness, but the source of consciousness. Self is not “a being,” but the Ground of Being. Thus we shall never discover an objective Self within different forms any more than we shall find an objective “I” among contents of the personality. Inasmuch as “I” can be termed “noself,” so Self can be termed “NoSelf.” Each are no-thing.11

Finally, note that “I” and Self are from a certain point of view one: “There are not really two selves, two independent and separate entities. The Self is one” (Assagioli 2000, 17). Assagioli considered this nondual unity a fundamental aspect of this level of human being, although he also understood that there could and should be a meaningful relationship between the person and Self as well. Here is Albert Einstein in a similar vein:

A human being is a part of a whole, called by us “universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separate from the rest—a kind of optical delusion of consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. (quoted in Levine 1982, 183)

SELF-REALIZATION

Many psychological thinkers besides Assagioli have recognized within the human being a sense of wisdom and direction that operates beyond, and often in spite of, the conscious personality. This has been called “the inner voice” and “Self” (Jung 1954), the “will to meaning” (Frankl 1962; 1967), the “destiny drive” (Bollas 1989), the “soul's code” (Hillman 1996), “the actualizing tendency” (Rogers 1980), and the “nuclear program” (Kohut 1984). In psychosynthesis, the source of this transpersonal impetus is considered to be Self.

Self-realization then has to do with our relationship to this deeper, transpersonal wisdom and direction within us, a relationship that can be characterized as that between the personal will of “I” and the transpersonal will of Self. Self-realization is the story of our contact and response to Self, our forgetting and remembering Self, our union and relatedness to Self, our movement in and out of alignment with the deepest currents of our being. Self-realization is the ongoing, lived, loving relationship between ourselves and our most cherished values, meanings, and purposes in life.

And if Self is transcendent-immanent throughout all levels of the personality and beyond, then such an ongoing love relationship may well take us into any and all levels of human experience. Relating to deeper Self may, for example, lead us to an engagement with our addictions and compulsions; or to the heights of creative and religious experience; or to the mysteries of noself and unitive experience; or to issues of meaning and mortality; or to a grappling with early childhood wounding. But throughout, whether in union or dialogue, the relationship is the thing. Self-realization is not here an arrival point, a particular state of consciousness, not something we must search far to attain. It is right here. Now.

So the dynamics of Self-realization have to do with how we perceive—or ignore—the deeper truth of our lives, and how we respond—or not—to this in the practical decisions of everyday life. It is fair to say that all theory and practice in psychosynthesis ultimately has to do with uncovering, clarifying, and responding to our own deeper sense of who we are and what our lives are about.

PERSONAL AND TRANSPERSONAL PSYCHOSYNTHESIS

Understanding Self-realization as a relationship with Self allows Self-realization to be distinguished from psychological or spiritual growth. While such growth can and does occur as we walk our path of Self-realization, it is a byproduct of this journey and not the goal. Accordingly, Self-realization can be differentiated from two important lines of human development discussed by Assagioli: personal psychosynthesis and spiritual or transpersonal psychosynthesis. Assagioli writes that personal psychosynthesis “includes the development and harmonizing of all human functions and potentialities at all levels of the lower and middle area in the diagram of the constitution of man” (Assagioli 1973b, 121). He is here referring to the oval diagram and to working with the lower and middle unconscious, a process leading toward a clearer sense of autonomy, personality integration, and personal power. The path of Self-realization may well lead us into this type of work because Self is transcendent-immanent throughout these levels and may invite us to engage them.

Distinct from personal psychosynthesis is the task of transpersonal psychosynthesis: “arriving at a harmonious adjustment by means of the proper assimilation of the inflowing superconscious energies and of their integration with the pre-existing aspects of the personality” (Assagioli 2000, 49). So transpersonal psychosynthesis is a process of integrating the contents and energies of the higher unconscious, of learning to contact and express transpersonal qualities, spiritual insights, and unitive states of consciousness. Here too, our ongoing relationship with Self may lead us to this type of integration because Self is transcendent-immanent throughout this level as well.12

As fundamental as personal and transpersonal psychosynthesis are, each has a limitation—each can leave out the other dimension. For example, an exclusive involvement with personal psychosynthesis may lead eventually to the existential crisis (Firman and Vargiu 1996) in which there is a loss of meaning and purpose in one's personal life. Likewise, an exclusive involvement with transpersonal psychosynthesis may lead to a crisis of duality (Firman and Gila 1997; 2002) in which there is the realization that higher unconscious experience does not automatically lead to a stable, embodied expression of this higher potential. Each crisis of transformation indicates an imbalance that is often righted as the missing dimension is included.

The journey of Self-realization will usually involve both personal and transpersonal growth at some point, and, more often perhaps, include them both in an ongoing way. But again, Self-realization is distinct from both types of growth. That is, if we, for example, ask a question such as, “To which type of growth am I called at this moment in my life?” we are thrown back on our sense of what is right for ourselves—to our relationship to Self, a relationship that is more fundamental than either of these two dimensions of growth. To answer such a question we can consult theories and therapists, teachers and sages, but even then it is up to us, based on our own sense of “rightness,” to follow our path as it wends its way through different dimensions of growth.

EXPANSION OF THE MIDDLE UNCONSCIOUS

Over time, it is common to find interplay between personal and transpersonal psychosynthesis such that both the higher and lower unconscious begin to be integrated. In this process we may find ourselves enjoying experiences of creativity, spiritual insight, and joy in our artistic or spiritual practice; then find ourselves joining a self-help program for a compulsion and thereby increasing our personal freedom; and perhaps entering therapy to uncover and heal aspects of experience related to childhood wounding.

All such exploration opens to, and integrates, the higher and lower unconscious into the middle unconscious. These heights and depths of ourselves are no longer sealed off from us, but begin to find their rightful place as structures supportive of our ongoing functioning, i.e., in the middle unconscious.

An expansion of the middle unconscious is also then an expansion of our experiential range. We hereby become more open to being touched by the beauty and joys of life, more open to the pain and suffering of ourselves and others, more able to live a life that embraces the heights and depths of human existence. In other words, our window of tolerance is widening.

But even then, while this expansion of the middle unconscious is often a product of following our path of Self-realization, the two processes yet remain distinct. Again, Self-realization is about our relationship with Self, a transcendent-immanent relationship that abides whether we are identified or disidentified, entranced or disentranced, on the heights or in the depths, functioning from an expanded middle unconscious or not. Self-realization refers to our loving journey with Self, not to any particular terrain the journey may take us through.