Chapter Three

Spiritual Empathy

Training in empathy not only helps one acquire a true understanding of others, but also bestows a wider humanness. It gives an insight into the wonder and mystery of human nature.

—Roberto Assagioli

As outlined earlier, the optimum unfolding of human being is a function of the deep union of “I” and Self, a union in altruistic, empathic love or agape, as this is revealed via authentic unifying centers. This unity not only gives birth to personal identity—“I”—but allows the expression of this identity in the world via one's unique gifts and callings—the blossoming of authentic personality and the journey of Self-realization.

We have seen too how this journey of the human spirit can be interrupted by an experienced break in the I-Self relationship—that is, by primal wounding—which leads to the formation of survival personality. Here unifying centers fail to embody the empathic love of Self, and so threaten an experience of nonbeing and annihilation rather than a sense of existence. Accordingly, one is not invited into authentic expression of oneself but instead is forced to live a life designed to survive and manage this primal wounding.

Clinical theory in psychosynthesis supports the potent impulse of Self-realization arising from altruistic love while recognizing that this impulse has been to a large extent concealed by wounding and the formation of survival personality. Survival personality obscures the journey of Self-realization, and the underlying wounding is involved in many, if not all, psychological disturbances presented to the clinician (see Firman and Gila 2002).

Given the centrality of empathic love in the emergence of personal identity, and the devastating effect of the experienced loss of this love, psychosynthesis therapy seeks most essentially to provide an authentic unifying center by which the love of Self is again realized. If a failure of love creates the wounding, it is only through love that healing can occur. Psychiatrist Scott Peck puts it quite plainly:

For the most part, mental illness is caused by an absence of or defect in the love that a particular child required from its particular parents for successful maturation and spiritual growth. It is obvious, then, that in order to be healed through psychotherapy the patient must receive from the psychotherapist at least a portion of the genuine love of which the patient was deprived. If the psychotherapist cannot genuinely love a patient, genuine healing will not occur. (Peck 1978, 175)1

Functioning as an embodiment of altruistic empathic love is what we are calling the expression of spiritual empathy, and is the central job of the psychosynthesis therapist. This means that the therapist joins clients on their journey of Self-realization. Therapists assume an impulse toward Self-realization in their clients, however hidden, and have faith that by remaining grounded in the spiritual union with them, this path will begin to reveal itself, however dimly. As in developmental and personality theory, spiritual empathy is again fundamental to psychosynthesis clinical theory. This chapter will examine the nature of spiritual empathy and begin to explore the task of the therapist in providing this.

THE NATURE OF SPIRITUAL EMPATHY

Before we discuss spiritual empathy, it can be helpful to understand what is meant by the term “empathy” alone.2 The word comes from the German word einfulung (May 1980, 75) or einfühlung (Margulies 1989; Shlien 1997), meaning “in-feeling” or “feeling into.” This “feeling into” can be seen in Martin Buber's definition of empathy: “to glide with one's own feeling into the dynamic structure of an object, a pillar, or a crystal or the branch of a tree, or even an animal or man, and as it were, to trace it from within” (Buber 2002, 114–115).

Thus the person who can skillfully maneuver an automobile is using empathy to in effect “become” the automobile; and the adept horseback rider “becomes one” with the horse, knowing and understanding the horse's experience; or we “feel into” art, music, and drama as we are absorbed in these (Adler 1957; Jung 1971); or the nature lover feels united with the life of the forest and the pain of its destruction.3

As many have pointed out, empathy so defined is a neutral capacity, one that may be used for good or ill (Kohut 1991; Moursund and Erskine 2004; Shlien 1997). For example, an all-too-common destructive use of empathy is using knowledge of another person's vulnerability to make precisely the mean remark that will “push a button” and cause an upset. Or as Kohut put it, “I figure out where your weak spots are so I can put the dagger in you” (Kohut 1985, 222). So the ability to “feel into” can be used to help or harm. This is one important reason that psychosynthesis therapy is not so concerned with plain empathy but focuses upon spiritual empathy.

Spiritual empathy denotes a “feeling into” the spirit that is the other. This is not essentially knowing the other person's physical experience, emotional reactions, or thought patterns, not simply knowing what the other is sensing, feeling, or thinking; rather, spiritual empathy is a recognition of the other as “I”—distinct, though not separate, from any content or form of experience.

In order for therapists to make contact at this level—to love at this level—they need to move toward recognizing that they too are distinct-but-not-separate from content; that is, they need to let go of roles, agendas, techniques, diagnoses, anything that would blind them to the other. It is at this level that a solidarity and even union with the other is realized—a connection in and through the Ground of Being, Self. In other words, spiritual empathy is a sense of unconditional love, an expression of agape, of altruistic love.

Carl Rogers (1961) approached this understanding of spiritual empathy by including “unconditional positive regard” and “prizing of the other” along with empathy among the necessary conditions for therapy.4 However, Assagioli believed that empathy itself gave rise to love, compassion, and communion:

Training in empathy not only helps one acquire a true understanding of others, but also bestows a wider humanness. It gives an insight into the wonder and mystery of human nature … we are induced to drop the ordinary attitude of passing judgment on others. Instead a sense of wide compassion, fellowship, and solidarity pervades us. (Assagioli 1973b, 89–90)

“Wide compassion, fellowship, and solidarity” indicates that for Assagioli empathy is not a neutral capacity to be used for good or ill. His empathy is a spiritual empathy, a realization of a profound union with other people in Spirit, the union of altruistic love. Expressing this love in spiritual empathy is the major task of the psychosynthesis therapist.5

SPIRITUAL EMPATHY IN ACTION: CINDY AND PHILIP

So spiritual empathy is not essentially a “feeling into” the experience of the other but instead a “feeling into” the spirit, the I-amness, that is the other. More accurately, it is the intentional recognition of a union with the other in altruistic love. But what does this actually mean in practice?

The difficulty in describing spiritual empathy is that we are not talking about specific types of interventions but about an attitude or stance, a way of being, that expresses altruistic love. Thus the forms of spiritual empathy are virtually infinite; everything depends on the particular individuals involved and their relationship. That said, we shall attempt to trace the operation of spiritual empathy in an interaction between Cindy, a distraught nineteen-year-old freshman premedical student, and her therapist, Philip.6

CINDY: You know, tests really, really freak me out. I go, “I'm going to fail.” Totally stressed out, heart pounding. Like it's the end of the world. It's way too much.

Listening to Cindy, Philip could feel himself inwardly preparing to treat the diagnosis “Specific Phobia, Situational Type” and so to perform well as a new employee of the counseling center. In rapid succession he thought of systematic desensitization, of addressing the negative cognitions, of focusing experientially on feelings and body, of exploring the childhood roots of the fear of failure, or of recommending a meditation practice.

Philip, however, bolstered by his ongoing spiritual practice and his own personal therapy, was able to remain disidentified from any of these options. Instead of seizing on any of them he simply allowed them to pass through his mind. He thus remained anchored in his empathic connection to Cindy and curious about where she wanted to go:

PHILIP: How would you like to be as you face your tests?

Philip's response clearly shows he is not focused simply on Cindy's experience, but more centrally on Cindy herself. He is obviously addressing the one with consciousness and will, the one who is having the experience (again this is only one of an infinite variety of responses that might express this attitude, including silence; it depends completely on the unique relationship involved). Consequently Cindy is able to look a little deeper at what it is she is seeking:

CINDY: Hmm, I dunno … calm, you know, peaceful. Not so like, “life and death.”

PHILIP: What would that be like?

CINDY: Awesome. I could relax, rest, not be so hyper. It'd be totally awesome. But then …

Here we see Cindy initially reaching for what it is she truly wants for herself in this situation, her own direction—a movement of Self-realization. This is a turning toward a deeper level in herself, a level of value and meaning to which she aspires, to which she feels called in this situation. As she attempts to pursue this direction further, however, she encounters something unexpected, saying, “But then.” Philip responds:

PHILIP: Then?

CINDY: Yeah, hmm. That's so weird.

PHILIP: What?

CINDY: My stomach jumped. I got afraid.

PHILIP: Yeah?

CINDY: Uh huh. You know, if I got all “whatever” about tests, maybe I wouldn't study so hard. Then I might really fail! That's scary.

PHILIP: So to relax would be scary?

CINDY: I guess so, yeah. That's too weird. I totally need to stress out. So I don't fail!

[Both sit in silence.]

So here Cindy realized that her presenting experience of stress was a surface feature of a deeper pattern, an identification or subpersonality within her that had been conditioned to use this stress in order to function, to succeed, to survive. At this point in the session, she is still free to choose any direction—a direction coming from her own sense of meaning and not Philip's. For example, she might find herself drawn to explore the fear of failure, the tightness in her chest, or the notion of the end of the world. The point is that Philip's way of being with her gives her the space to become conscious and volitional in the process. Yet—note well—Philip is active, although all of his activity seeks to support Cindy's own sense of direction. Let us see where she goes.

CINDY: So let's see, I actually need my nervousness. Yeah. What a trip. But ugh, this sucks. It's way too hard on me. There has to be another way to get myself going.

PHILIP: Another way?

CINDY: Yeah, I don't know. People I look up to don't seem to need to terrorize themselves to get things done!

PHILIP: Like?

CINDY: Hmm, maybe my best friend, Clara. There's Schweitzer. Eleanor Roosevelt. They all have passion, a purpose.

PHILIP: And you?

CINDY: Yeah, that's right. I do really care about being a doctor, you know. I've wanted to help people since I was little. That's the only reason I'm in school at all.

PHILIP: Do you remember when you first wanted to be a doctor?

CINDY: For sure, yes, when my mother was so sick and I got to know Dr. Levenson, her doctor. The way he was with her was awesome. I loved Dr. Levenson and just knew that's what I wanted to do with my life. It was my dream, still is.

PHILIP: If you stay with this, with this dream, how do you imagine you might be with your papers and tests?

CINDY: Hmm. Yes, I'd just be in touch with this the whole time. I'd know I was following my dream. It would be like having Dr. Levenson with me the whole time. Maybe I wouldn't feel so scared about failing then.

PHILIP: Take a moment and imagine how that would be.

CINDY: [Closing her eyes.] Yeah, much more peaceful, but passionate at the same time. I can even hear Dr. Levenson saying, “You can do it.” I feel sort of like there is this larger thing going on and I don't have to sweat the small stuff. Tests don't feel so scary from this place.

So in spiritual empathy Philip actively addresses the person and not simply the contents of consciousness, the process, or the experience. He knows her as someone with the potential to access her own inner wisdom and direction. He is “feeling into” her spirit and her path of Self-realization with love and respect. Accordingly, Cindy's consciousness and will emerge, her I-amness blossoms. As this happens, she begins to reconnect to a deeper motivation that she has somewhat forgotten, and to an authentic unifying center (Dr. Levenson) that supports this motivation.

Over the course of therapy, Cindy subsequently discovered that this fear of failure was rooted in her relationship with an emotionally distant and disapproving father, worked with related feelings of abandonment and grief, and also effectively used imagery and relaxation techniques to access more peace in facing school tests. But let us maintain a focus on the role spiritual empathy played at this critical point in the therapy.

THE ROLE OF SPIRITUAL EMPATHY

In the above dialogue Philip avoided the temptation to react from his own therapeutic agenda—which would have made Cindy into an object of his own conclusions and plans—and instead attuned to her as “in but not of” these experiences. Thus safely held in love, Cindy was free to explore her experience of the pattern, and gradually disidentified from it, uncovering the core dynamic that had been controlling her. In technical terms, “I” emerged with consciousness and will, transcendent-immanent within the contents of experience.

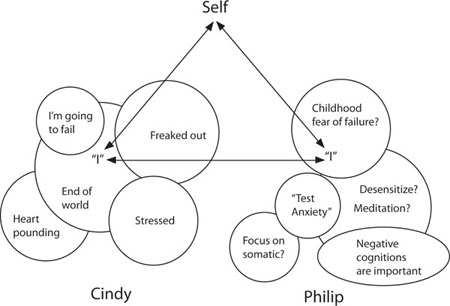

Spiritual empathy not only facilitated an emergence of “I” but also an engagement with Self-realization. That is, discovering her wish for peace and calm in facing tests drew upon her own sense of direction and meaning, a call or invitation from something deeper within her. Responding to this call led to the subsequent encounter with the fear—the obstacle to that direction—and so to working with that fear. Clearly Cindy's path of healing and growth was unfolding within the empathic field between her and Philip. Their encounter is diagrammed in Figure 3.1.

This figure shows Philip and Cindy within a field of spiritual empathy, held in altruistic love. Via his own connection to Self—a lived connection to the deeper truth of life beyond his identifications and roles—Philip remained disidentified from the designs of his professional ego. He thereby could see through his own experience and so through Cindy's experience as well, addressing Cindy and not simply the content of her experience. As he contacted her in this I-Thou way, she found a “secure base” (Bowlby 1988) from which to discover and pursue her path—the consciousness and will of “I” emerged and Self-realization unfolded.

FIGURE 3.1

The triangle depicted in this illustration can be seen as fundamental to psychosynthesis therapy. The therapist's job is to remain in conscious contact with Self and, thus rooted in this “empathic ground” (Blackstone 2007), find the wherewithal to see, understand, and love clients at this spiritual level—as they themselves, not as objects to be diagnosed and treated. Clients are thereby given the opportunity to awaken and tread their path of Self-realization more consciously. Therapists operate from this “love triangle” as the context of therapy, even though the triangle may be hidden from clients struggling with their issues.

CONTINUITY OF BEING, RESISTANCE, AND SELF-REALIZATION

Since Philip was completely with Cindy in each step she took, she experienced a “continuity of being” (Winnicott 1987), that is, she experienced herself as present and volitional through each moment of her self-exploration. Held continuously in being, she had the space and time to listen to herself, hear deeper currents within her, and begin to follow her own sense of what was right for her—her Self-realization.

However, if Philip had decided unilaterally to treat her stress, this continuity would have been disturbed. Philip would have missed the sequence of steps Cindy needed to take on her path, missing in this case the step of her discovering she was using the stress as a motivator. Philip's subsequent therapeutic efforts would then have been at odds with Cindy's unfolding path, he seeking to treat the stress and she unconsciously holding onto it. Cindy would then be left with the choice to submit or resist.

SUBMITTING TO THE THERAPIST

If Cindy decided to submit to Philip and work immediately with the stress, she would do so with a diminished sense of her own consciousness and will; she would be following Philip's agenda and not her own sense of direction. Philip would have assumed the role of the expert responsible for understanding and managing her emerging experience. Swept into the therapist's world like this, the client becomes the dependent object of the therapist-as-god.

Moreover, if Cindy had been led into the underlying childhood wounding from this impoverished position, she may well have found herself prematurely deep in painful feelings with little knowledge of how she arrived there, no direct understanding of how this related to her life issues, and with diminished personal power to engage and integrate the experience. Such an experiential leap can be confusing, and can even lead to feeling overwhelmed, flooded, and re-traumatized.

Such a capitulation to the authority of the therapist can eventually lead to what has been called a “pseudoalliance,” a relationship that is “based on the patient's compliant identification with the analyst's point of view in order to safeguard the therapeutic relationship” (Stolorow, Brandchaft, and Atwood 1987, 11). In a pseudoalliance, the client forms a survival personality playing to the therapist as survival unifying center—precisely the way the client survived earlier nonempathic environments. The client here trades one survival unifying center for another.

Ironically, however, submitting to the therapist can also produce positive experiences. For example, Philip might have unilaterally taken Cindy into the underlying abandonment and grief, or focused on her somatic experience, or addressed the negative thoughts, and thereby brought her some relief from her distress. What would have been lost, however, is Cindy. Cindy would have missed the experience of herself as a responsible “I am” who has the wisdom and will to find her own way, drawing on resources she chooses to trust. In short, her continuity of being would be disrupted even though she experienced insight and relief.

However seemingly positive the effect of such interventions, they nevertheless are empathic failures and amount to oppression—the client is here seduced to submit. This is not the liberation of “I” in authentic personality but rather the creation of another type of survival personality. Thus nonempathic interventions like these—however seemingly beneficial they may appear—are not only antitherapeutic but, we believe, constitute an unethical use of the therapist's power (see chapter 6).

RESISTING THE THERAPIST

Cindy on the other hand might have refused to submit to Philip's nonempathic interventions. She might then be considered a “resistant” client. This is perhaps a correct term to use here, as long as it is understood that what the client is resisting is not the process itself but the therapist's pushing the process. That is, Cindy would not be resisting an encounter with her fear of failure and abandonment, but the loss of her own sequence, pace, and timing in dealing with these. She is resisting the violation of her world, a breaking of her continuity of being, a re-traumatization of primal wounding.7

Therapists who do not fully appreciate the power of primal wounding, who believe that defenses are simply illusions or veils that can be torn asunder, can be tempted here to deal with resistance simply as clients' misguided attachment to their early conditioning. Here the survival patterns are seen as mere problems in awareness, of being lost in illusions that need to be dispelled by any means available. When this superficial understanding is coupled with the power the therapist (or spiritual teacher) has vis-à-vis the client, one has a recipe for placing the client in precisely this oppressive resist-or-submit dilemma.8

Resistance to the therapist's authority can eventually lead to an impasse in which the therapy grinds to a “mysterious” halt, and eventually to the client terminating therapy altogether. And throughout, unknowing therapists can lay the blame squarely on the “client's resistance” and so remain oblivious to their central role in creating this resistance. One wise counseling textbook admonishes therapists: “If you are too intent on your own agenda, too concerned with hurrying up the process or with proving that you know what is wrong and what should be done about it, you are very likely to create such an impasse” (Moursund and Kenny 2002, 92).

But in Cindy's case Philip's empathic love supported her own personal awareness and choices (her will) each step of the way. This continuity of being meant she was aware of each incremental step moment-by-moment and so could maintain a connection to her own power, meaning, and direction throughout. She was empowered to continue her journey, both within therapy and outside of it. Her sense of self and her sense of her own truth guided her healing and growth—not Philip—and so her journey of Self-realization was facilitated.

Note again that Philip's work was not fundamentally about his professional role, therapeutic techniques, or diagnostic insight, but about knowing himself as deeper than all of these. To the extent he was not caught up in the machinations of his own inner world, Cindy had in effect a lifeline into her world, one that she used to gradually find her own way. His disidentification allowed her disidentification, his detachment allowed her detachment, his love allowed her love—in effect, Philip facilitated her journey of Self-realization by walking his own journey.

THE TASK OF THE PSYCHOSYNTHESIS THERAPIST

So spiritual empathy involves realizing our connection with the other beyond any condition of the personality, yet manifest in all conditions of the personality. This is an act of love, a recognition of the essential oneness of ourselves and the other in Self, in Spirit. In Assagioli's words, this is an altruistic love deriving from “a sense of essential identity with one's brothers [and sisters] in humanity” (Assagioli 1973b, 94).

Knowing this union allows the therapist to express spiritual empathy and so to function as an authentic unifying center—“an indirect but true link, a point of connection between the personal man and his higher Self” (Assagioli 2000, 22). It is as if being “flows through” the therapist from Self, nurturing the I-amness of the other, or, more accurately, the therapist's realization of a communion in Spirit—empathic love—allows the client to access that union as well, and thus a relationship with Self can be emergent for the client.

However we conceptualize it, spiritual empathy offers the client increased self-empathy, disidentification, personal power, and a sense of meaning and direction—“I” emerges and Self-realization unfolds.9

INTERNALIZING THE THERAPIST

Furthermore, following the developmental theory described in chapter 2, the therapist as an authentic unifying center allows clients to form an internal authentic unifying center, thereby beginning to function as an authentic unifying center for themselves. In effect, the client internalizes the empathic presence of the therapist. Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Willard Gaylin's (2000, 284) psychotherapy text puts it poignantly: “Whatever the symptom, the patient is no longer alone with it. He has a secret and silent ally who is always with him. One of the most profound facets of therapy is the internalization of the therapist” (quoted in Moursund and Kenny 2002, 109). And said from a neuroscience perspective:

A patient doesn't become generically healthier; he becomes more like the therapist…. The person of the therapist will determine the shape of the new world a patient is bound for; the configuration of his limbic Attractors fixes those of the other. Thus the urgent necessity for a therapist to get his emotional house in order. His patients are coming to stay, and they may have to live there for the rest of their lives. (Lewis, Amini, and Lannon 2001, 186–187)

Assagioli writes quite explicitly about this process, saying that the therapist “represents or constitutes a model or a symbol and is introjected in some measure by the patient” (Assagioli 2000, 5). He goes on to say that this internalization allows the therapist to become less important as a link to Self, and that the therapist is gradually “replaced by the Self, with whom the patient establishes a growing relationship, a ‘dialogue,’ and an increasing (although never complete) identification.” In other words, clients begin to discern and follow their own values and direction in life—the client's own path of Self-realization emerges (as illustrated in Figures 2.3 and 2.4).

BEING AN AUTHENTIC UNIFYING CENTER

If healing and growth are a function of internalizing the empathic love of the therapist, it is crucial the therapist function as an authentic unifying center in a consistent way—“the urgent necessity for a therapist to get his emotional house in order.” What does this mean?

As seen in the work of Philip and Cindy, a key factor in being able to function as an authentic unifying center is the ability to relinquish one's own frame of reference. Only in this way can we be free to love clients within their frame of reference, their world of experience and meaning. This ability to disidentify from one's experiential world is an essential responsibility of the psychosynthesis therapist (and yes, of parents, lovers, and friends, but those are other books). Assagioli addressed this disidentification when he wrote of relinquishing the “self-centeredness that prevents understanding others”:

While less obvious and crude than selfishness, it [self-centeredness] is also a great hindrance because of its tendency to refer everything to the personal self, to consider everything from the angle of one's own personality, to concentrate solely on one's own ideas and emotional reactions. It can be well hidden, since it can coexist with wholehearted attachment to others and with acts of sacrifice. The self-centered individual may not be and often is not at all selfish. He may be altruistic and sincerely want to do good. But he wants to do it in his own way…. Thus, with the best of intentions, he can do actual harm, like the kindly monkey in the story, who, seeing a fish in the water, rushes to rescue it from drowning by carrying it up into the branches of a tree. (Assagioli 1973b, 87–86)

Thus our best intentions for our clients, our true caring and love, and our most skillful therapeutic interventions, all can be misdirected and even harmful if we are centered within our own “ideas and emotional reactions”—our own frame of reference, our own experiential world. Clearly, if Philip had remained centered in his own world, however well-intentioned and loving he might have been, he would not have been able to love Cindy as he did. Thus therapists must always ask themselves if they are joining the client in the client's world or standing apart in their own world. Only the former allows for empathic love, for altruistic love, for spiritual empathy.

So it comes to this: providing altruistic love in spiritual empathy, functioning as an authentic unifying center, demands dying to one's own frame of reference, dying to one's own experiential world. Spiritual empathy is not essentially about knowing the experience of the client, feeling warm and loving toward the client, or about a sincere intention to help the client (although these may be involved)—it is much more fundamentally about the therapist “dying to self.” This may be the most difficult task of the psychosynthesis therapist, as we shall see in the next chapter.