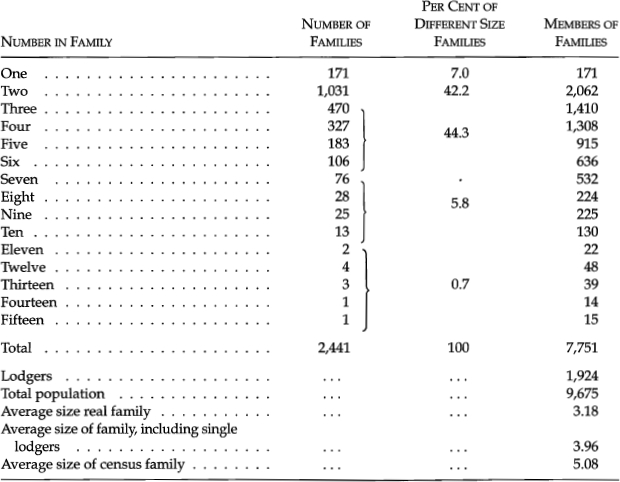

27. The Size of the Family—There were in the Seventh Ward, in 1896, 7,751 members of families (including 171 persons living alone), and 1,924 single lodgers.1 The average size of the family, without lodgers and boarders, was 3.18.

FAMILIES ACCORDING TO SIZE

With the whole population of the ward included, the average size was about four, and counting married and single lodgers as part of the renting family, the average size is about five.2 In any case the smallness of the families is remarkable, and is probably due to local causes in the ward, to the general situation in the city and to development in the race at large. The Seventh Ward is a ward of lodgers and casual sojourners; newly married couples settle down here until they are compelled, by the appearance of children, to move into homes of their own, and these in later years are being chosen in the Twenty-sixth, Thirtieth and Thirty-sixth wards, and uptown. Some couples leave their families in the South with grandmothers and live in lodgings here, returning to Virginia or Maryland only temporarily in summer or winter; a good many men come here from elsewhere, live as lodgers and support families in the country; then, too, childless couples often work out, the woman at service and the man lodging in this ward; the woman joins her husband once or twice a week, but does not lodge regularly there, and so is not a resident of the ward; such are the local conditions that affect greatly the size of families.3

The size of families in cities is nearly always smaller than elsewhere, and the Negro family follows this rule; late marriages among them undoubtedly act as a check to population; moreover, the economic stress is so great that only the small family can survive; the large families are either kept from coming to the city or move away, or, as is most common, send the breadwinners to the city while they stay in the country. It is of course but conjecture to say how far these causes are working among the general Negro population of the country; but considering that the whole race has to-day begun its great battle for economic survival, and that few of the better class, male or female, can expect to get married early in life, it is fair to expect that for several decades to come the average size of the Negro family will decrease until economic well-being can keep pace with the demands of a rising standard of living; and that then we shall have another era of goodsized though not very large Negro families.4

As has before been intimated, the difficulty of earning income enough to afford to marry, has had its ill effects on the sexual morality of city Negroes, especially, too, since their hereditary training in this respect has been lax. It is, therefore, fair to conclude that a number of the families of two are simply more or less permanent cohabitations; and that a large number of families are centres of irregular sexual intercourse. Observation in the ward bears out this conclusion, and shows that fifty-eight of the families of two were certainly unmarried persons.

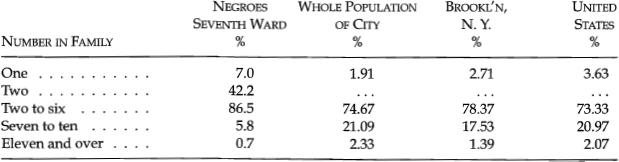

The result of all these causes is shown in the following table, although the comparison is not strictly allowable; the real family of the Negroes is compared with the census family of other groups, and this exaggerates the proportion of the smaller families among the Negroes:

Further comparison with France may be made:5

| NUMBER IN FAMILY | NEGROES SEVENTH WARD | FRANCE |

| One | 7.0 | 14.0 |

| Two to three | 61.5 | 41.3 |

| Four to five | 20.9 | 29.8 |

| Six or more | 10.6 | 14.5 |

Making allowance for the errors of this comparison, it nevertheless seems true that the conditions of family life in the ward are abnormal and characterized by an unusually large number of families of two persons.

There are no statistics for the Negro families of the whole city such as would serve to eliminate the local peculiarities of the Seventh Ward. General observation would indicate in the Fifth and Eighth wards similar conditions to the Seventh. In most of the other wards conditions are different, and in all probability vary widely from these crowded central wards. Nevertheless, throughout all of them large families are not the rule, the number of bachelors and lodgers is considerable, and there is some cohabitation, although this is, in the city at large, much less prevalent than in the Seventh Ward. It would seem, therefore, that the indications of our study of conjugal condition were here emphasized, and that the Negro urban home has commenced a revolution which will either purify and raise it or more thoroughly debauch it than now; and that the determining factor is economic opportunity. The full picture of this change demands statistics of births and marriages from year to year. These unfortunately are not so registered as to be even partially reliable. Both the birth and marriage rate, however, are in all probability steadily decreasing.6 The death rate also comes in here as a factor, not only by reason of the great infant mortality but also on account of the excessive death rate of the men. In all this one catches a faint glimpse of the intricacy and far-reaching influence of the Negro problems.

28. Incomes—The economic problem of the Negroes of the city has been repeatedly referred to. We now come directly to the question, What do Negroes earn? In a year about what is the income of an average family? Such a question is difficult to answer with anything like accuracy. Only returns based on actual written accounts would furnish thoroughly reliable statistics; such accounts cannot be had in this case. The few that keep accounts would in many cases naturally be unwilling to produce them. On the other hand, the great mass of people in the lower walks of life scarcely know how much they earn in a year. The tables here presented, therefore, must be regarded simply as careful estimates. These estimates are based on three or more of the following items: (1) The statement of the family as to their earnings. Some of the better class gave a general estimate of their average yearly income; most gave the wages earned per week or month at their usual occupation. (2) The occupations followed by the several members of the family; (3) the time lost from work in the last year or the time usually lost; (4) the apparent circumstances of the family judging from the appearance of the home and inmates, the rent paid, the presence of lodgers, etc.

In most cases the first item was given the greatest weight in settling the matter, but was modified by the others; in other cases, however, either this statement could not be obtained or was vague, and in a few instances evidently false. In such circumstances the second item was decisive: the occupations followed by the mass of Negroes are paid according to a pretty well-known scale of prices; a hotel waiter’s income could be pretty accurately fixed without further data. The third item was important in many occupations; stevedores, for instance, receive generally twenty cents per hour; nevertheless, few if any earn $600 a year, because they lose much time between ships and in winter. Finally, as a general corrective to deception or inadvertence the circumstances of home life as seen by the investigator on his visit, the rent paid—an item which could be pretty accurately ascertained—the number of lodgers, the occupation of the housewife and children—all these items served to confirm or throw doubt on the conclusions indicated by the other data, and were given some weight in the final judgment.

Thus it can easily be seen that these returns may contain, and probably do contain, considerable error. On the one hand they cannot be as accurate as returns based on income tax reports, and on the other hand they are probably more reliable than data founded solely on the bare statements of those asked. The personal judgment of the investigator enters into the determination of the figures to a larger extent than is desirable, and yet it has been limited as carefully as the nature of the inquiry permitted.7

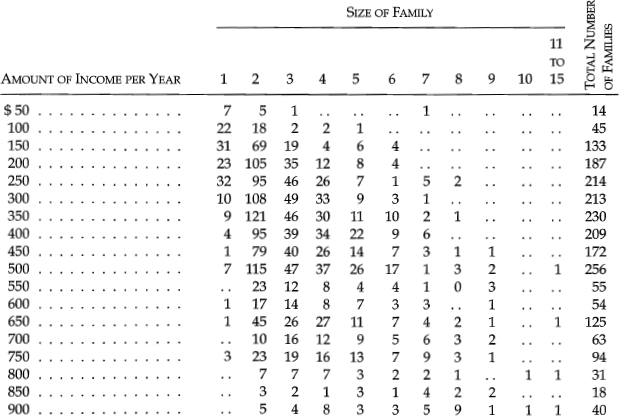

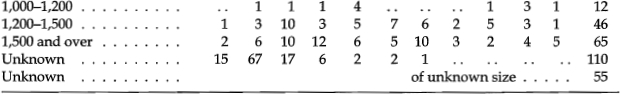

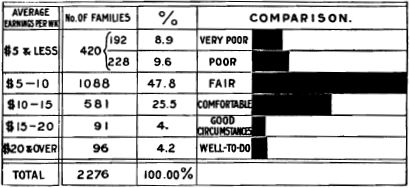

The income according to size of family is indicated in the next table. From this, making the standard a family of five, and making some allowance for larger and smaller families, we can conclude that 19 per cent of the Negro families in the Seventh Ward earn five dollars and less per week on the average; 48 per cent earn between $5 and $10; 26 percent, $10–$15, and 8 per cent over $15 per week. Tabulating this we have:

INCOMES, ACCORDING TO SIZE OF FAMILY IN SEVENTH WARD, 1896

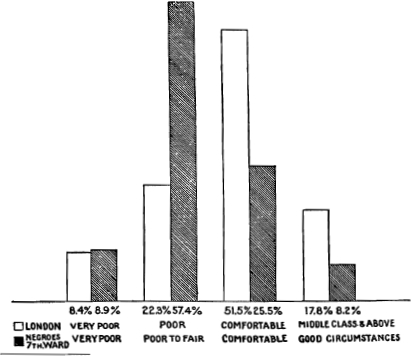

It is difficult to compare this with other groups because of the varying meaning of the terms poor, well-to-do, and the like. Nevertheless, a comparison with Booth’s diagram of London will, if not carried too far, be interesting:8

POVERTY IN LONDON AND AMONG THE NEGROES OF THE SEVENTH WARD OF PHILADELPHIA.

The chief difficulty of this comparison lies in the distribution of the population between the “poor” and “comfortable;” probably the former class among the Negroes is here somewhat exaggerated. At any rate, the division between these two grades is in the Seventh Ward much less stable than in London since their economic status is less fixed. In good times perhaps 50 per cent of the Negroes could well be designated comfortable, but in time of financial stress vast numbers of this class fall below the line into the poor and go to swell the number of paupers, and in many cases of criminals. Indeed this whole division into incomes of different classes is, among the Negroes, much less stable than among the whites, just as it used to be less stable among the whites of fifty years ago than it is among those of to-day.

The whole division into “poor,” “comfortable” and “weIl-to-do” depends primarily on the standard of living among a people. Let us, therefore, note something of the income and expenditure of certain families in different grades.9 The very poor and semi-criminal class are congregated in the slums at Seventh and Lombard Streets, Seventeenth and Lombard, and Eighteenth and Naudain, together with other small back streets scattered over the ward. They live in one- and two-room tenements, scantily furnished and poorly lighted and heated; they get casual labor, and the women do washing. The children go to school irregularly or loaf on the streets. This class does not frequent the large Negro churches, but part of them fill the small noisy missions. The vicious and criminal portion do not usually go to church. Those of this class who are poor but decent are next-door neighbors usually to pronounced criminals and prostitutes. The income and expenditure of some of these families follow.

Family No. 1 lives in one of the worst streets of the ward, surrounded by thieves and prostitutes. There are three persons in the family: a woman of thirty-four, with a son of sixteen and a second husband of twenty-six. Both the husband and son are out of work, the former being a waiter and the latter a bootblack. They live in one filthy room, twelve feet by fourteen, scantily furnished and poorly ventilated. The woman works at service and receives about three dollars a week. They pay twelve dollars a month for three rooms, and sub-rent two of them to other families, which makes their rent about three dollars.

Their food costs them about $1.00 a week and the fuel 56 cents a week during the winter. Their expenditure for other items is varying and indefinite; beer, however, comes in for something. Their whole expenditure is probably $125–$150 a year, of which the woman earns at least $100.

Family No. 2 has a yearly budget as follows for two persons:

| Rent, @ $4 a month | $48.00 |

| Food—Bread, pork, tea, etc., @ $1.44 a week | 74.88 |

| Fuel, 20–47 cents a week | 16.60 |

| $139.48 |

Other items would bring this up to about $150 to $175.

Family No. 3, consisting of one person, reports the following budget, not including rent:

| Food | $30.00 |

| Fuel | 15.00 |

| Clothing | 10.00 |

| Amusements | 1.50 |

| Sickness, etc | 10.00 |

| Other purposes | 15.00 |

| Total, per year | $81.50 |

The rent of such a family would not exceed $40, making the total expenditure about $121.50.

Family No. 4—four persons—man and wife and two babies, living in one room, spend as follows:

| Rent, @ $3 a month | $36.00 | |

| Food—Weekly: milk | $0.28 | |

| pork | .70 | |

| bread | .35 | |

| 1.33 | 69.16 | |

| Fuel, 20–98 cents a week | 18.00 | |

| $123.16 |

The man has work one and one-half weeks in the month as a wire fence maker, when regularly employed, which is about half the time. The rest of the time he takes care of the babies while his wife works at service. The last two families seem respectable, but unfortunate. The other two are doubtful.

The “poor” are a degree above these cases; they are composed of the inefficient, unfortunate and improvident, and just manage to get enough to eat, a little to wear, and shelter. A specimen family is composed of six persons—man and wife, a widowed daughter, two grandsons of thirteen and eleven, and a nephew of twenty-eight. They live in three rooms, with poor furniture and of fair cleanliness. The father and nephew are laborers, often out of work. The mother does day’s work and the daughter is at service. They spend for:

| Rent—$8 per month | $96.00 |

| Food—$2.16 a week | 112.32 |

| Fuel—50–84 cents a week | 31.20 |

| $239.52 |

Clothing, etc., will bring this total to $250–$275. This is an honest family, belonging to one of the large Baptist churches.

Family No. 5, a mother and child, expends for

| Food | $96.00 |

| Fuel | 30.00 |

| Clothing | 30.00 |

| Amusements | 10.00 |

| Sickness | 15.00 |

| Other purposes | 25.00 |

| Total | $206.00 |

To this must be added house-rent, bringing the total to $250 or $275.

We next come to the great hard-working laboring class—the 47 per cent of the population which is, on the whole, most truly representative of the mass. They live in houses with three to six rooms, nearly always well furnished; they spend considerable for food and dress, and for churches and beneficial societies. They are honest and good-natured for the most part, but are not used to large responsibility.

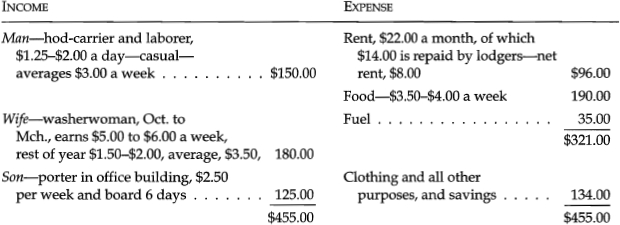

No. 6, a family of three from this class—man, wife and seventeen-year-old son—earn and spend as follows:

This family occupies a seven-room house, but rents out three of the rooms to lodgers. They have a nicely furnished parlor.

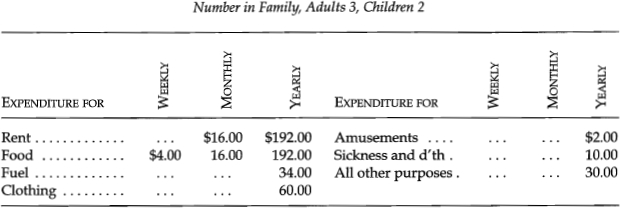

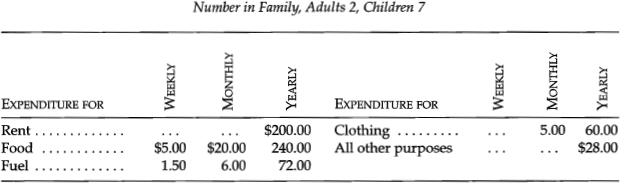

Three other families of the same class follow:

No. 7. Expenditure for one year, $338 (not including rent). Number in family, adults 2, children 2.

| Food | $110.00 |

| Fuel | 40.00 |

| Clothing | 50.00 |

| Amusements | 35.00 |

| Sickness | 40.00 |

| Other purposes | 63.00 |

NO. 8. EXPENDITURE FOR ONE YEAR, $520.00

NO. 9. EXPENDITURE FOR ONE YEAR, ABOUT $600.00

Three other budgets are appended, representing a still better class:

No. 10.

| Total income, $840.00 | |

| Rent | $192.00 |

| Food | 260.00 |

| Fuel | 50.00 |

| Clothing | 25.00 |

| Amusements | 15.00 |

| $542.00 |

This is a small family—mother and daughter—who are evidently saving money. The daughter is a teacher.

No. 11. Total expenditure, exclusive of rent, $683.

| Food | $378.00 |

| Fuel | 45.00 |

| Clothing | 100.00 |

| Amusements | 20.00 |

| Sickness | 50.00 |

| Other purposes | 90.00 |

There are four adults and three children in this family.

No. 12. Total expenditure, exclusive of rent, $805.

| Food | $420.00 |

| Fuel | 60.00 |

| Clothing | 150.00 |

| Amusements | 20.00 |

| Sickness | 5.00 |

| Travel, and other purposes | 150.00 |

This is one of the best families in the city; they keep one servant. There are three adults and two children in the family.

The class to which these last families belong is often lost sight of in discussing the Negro. It is the germ of a great middle class, but in general its members are curiously hampered by the fact that, being shut off from the world about them, they are the aristocracy of their own people, with all the responsibilities of an aristocracy, and yet they, on the one hand, are not prepared for this role, and their own masses are not used to looking to them for leadership. As a class they feel strongly the centrifugal forces of class repulsion among their own people, and, indeed, are compelled to feel it in sheer self-defence. They do not relish being mistaken for servants; they shrink from the free and easy worship of most of the Negro churches, and they shrink from all such display and publicity as will expose them to the veiled insult and depreciation which the masses suffer. Consequently this class, which ought to lead, refuses to head any race movement on the plea that thus they draw the very color line against which they protest. On the other hand their ability to stand apart, refusing on the one hand all responsibility for the masses of the Negroes and on the other hand seeking no recognition from the outside world, which is not willingly accorded—their opportunity to take such a stand is hindered by their small economic resources. Even more than the rest of the race they feel the difficulty of getting on in the world by reason of their small opportunities for remunerative and respectable work. On the other hand their position as the richest of their race—though their riches are insignificant compared with their white neighbors—makes unusual social demands upon them. A white Philadelphian with $1500 a year can call himself poor and live simply. A Negro with $1500 a year ranks with the richest of his race and must usually spend more in proportion than his white neighbor in rent, dress and entertainment.

In every class thus reviewed there comes to the front a central problem of expenditure. Probably few poor nations waste more money by thoughtless and unreasonable expenditure than the American Negro, and especially those living in large cities like Philadelphia. First, they waste much money in poor food and in unhealthful methods of cooking. The meat bill of the average Negro family would surprise a French or German peasant or even an Englishman. The crowds that line Lombard street on Sundays are dressed far beyond their means; much money is wasted in extravagantly furnished parlors, dining-rooms, guest chambers and other visible parts of the homes. Thousands of dollars are annually wasted in excessive rents, in doubtful “societies” of all kinds and descriptions, in amusements of various kinds, and in miscellaneous ornaments and gewgaws. All this is a natural heritage of a slave system, but it is not the less a matter of serious import to a people in such economic stress as Negroes now are. The Negro has much to learn of the Jew and Italian, as to living within his means and saving every penny from excessive and wasteful expenditures.

29. Property—We must next inquire what part of these incomes have been turned into real property. Philadelphia keeps no separate account of her white and Negro real estate owners and it is very difficult to get reliable data on the subject. Even the house-to-house inquiry could but approximate the truth on account of the number of houses owned by Negroes but rented out through white real estate agents. From the returns it appears that 123 of the 2441 families in the Seventh Ward or 5.3 per cent own property in that ward; seventy-four other families own property outside the ward, making in all 197 or 8 per cent of the families who are property holders. It is possible that omissions may raise this total to 10 per cent. The total value of this property is partly conjectural but a careful estimate would place it at about $1,000,000, or 4½ per cent of the valuation of a ward where the Negroes form 42 per cent of the population.

Two estimates for the whole city represent the holdings of the well-to-do Negroes, that is, those having $10,000 and more of property, as follows:10

| From | $10,000 to $15,000 | 27 |

| ” | 15,000 to 25,000 | 10 |

| ” | 25,000 to 50,000 | 11 |

| ” | 50,000 to 100,000 | 4 |

| ” | 100,000 to 500,000 | 1 |

| 53 |

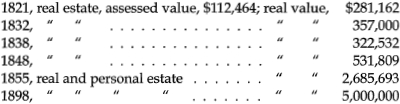

In all, these persons represent an ownership of at least $1,500,000. The other property holders can only be estimated; the total ownership of property by Philadelphia Negroes must be at least five millions, not including church property. Comparing this with estimates in the past, we have:11

In 1849 the returns of the investigation showed that 7.4 per cent of the Negroes in the county owned property, and 5.5 per cent in the city proper, compared with 5.3 per cent in the Seventh Ward to-day. In this comparison, however, we must consider the enormous increase in the value of Philadelphia real estate.

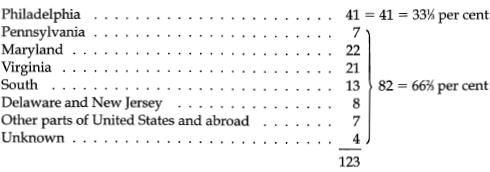

Taking the heads of the 123 families known to live in the Seventh Ward and to own real estate we find that they were born as follows:

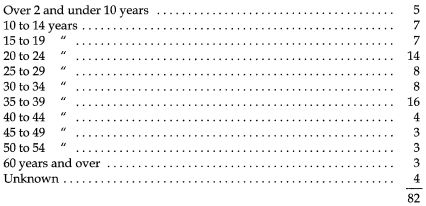

The eighty-two not born in Philadelphia have lived there as follows:

Nineteen have lived less than twenty years in the city and fifty-nine, twenty years or more.

The occupations of the 123 property owners were as follows:

| Caterers | 22 |

| Waiters | 12 |

| Porters and Janitors | 10 |

| Housewives | 9 |

| Laundresses | 8 |

| Mechanics | 7 |

| Coachmen | 6 |

| Clerks in public service | 4 |

| Drivers and teamsters | 4 |

| Upholsterers | 3 |

| Employment agents | 3 |

| Merchants | 3 |

| Stewards | 3 |

| Ministers | 3 |

| Hod-carriers and laborers | 2 |

| Policemen and watchmen | 2 |

| Hotel keepers and restaurateurs | 3 |

| Cooks | 2 |

| Undertakers | 2 |

| School-teachers | 2 |

| Barbers | 2 |

| Physicians | 2 |

| Shrouder of dead | 1 |

| Newspaper publisher | 1 |

| Real estate dealer | 1 |

| Sexton | 1 |

| No occupation | 3 |

| Unknown | 2 |

| 123 |

This shows that the real estate owners are either Philadelphia born or old residents and that the mass of them are caterers and house servants, with a sprinkling of those representing the newer employments as clerks in public service, merchants, and the like.

Of these one hundred and twenty-three families

| 62 | own the houses they occupy. |

| 20 | own the houses they occupy, and also other real estate in the city. |

| 7 | own the houses they occupy, own other real estate in the city, and also own real estate elsewhere. |

| 5 | own homes outside the city, and other real estate elsewhere. |

| 22 | own real estate in the city. |

| 7 | own real estate in the city and elsewhere also. |

In other words, 89 own homes in the city, and 34 own real estate somewhere.

Returns from forty of these holders indicate a total holding of $250,000, or if we add in one large estate, $650,000. Other less definite but fairly reliable returns raise the total ownership of property in the Seventh Ward to $1,000,000 or more. Sixty-three of the seventy-four owning property outside the city report $49,010 in real estate.12 In none of these returns has there been any account of the mortgage indebtedness taken, nor is there any means of ascertaining this debt.13

On the whole the statistics show comparatively few Negro property holders in Philadelphia. In a city where the percentage of home owners is unusually large, over 94 per cent of the Negroes appear from the imperfect returns available to be renters. There are several reasons for this: first, the Negroes distrust all saving institutions since the fatal collapse of the Freedmen’s Bank; secondly, they have difficulty in buying homes in decent neighborhoods; thirdly, the rising price of real estate, and the falling off of wage and industrial opportunity for the Negro must be taken into account. Finally a curious effect of color prejudice, to be discussed later, has had enormous influence in concentrating Negro population in localities where it was hard to buy homes. All these are cogent reasons, and yet they are not enough to excuse the Negroes from not buying much more property than they have. Much of the money that should have gone into homes has gone into costly church edifices, dues to societies, dress and entertainment. If the Negroes had bought little homes as persistently as they have worked to develop a church and secret society system, and had invested more of their earnings in savings-banks and less in clothes they would be in a far better condition to demand industrial opportunity than they are to-day.

This does not mean that the Negro is lazy or a spend-thrift; it simply means misdirected energies which cause the Negro people yearly to waste thousands of dollars in rents and live in poor homes when they might with proper foresight do much better.

There are some signs of awakening to this fact among the Negroes. Lately they are just beginning to understand and profit by the Building and Loan Associations. Forty-one families in the Seventh Ward, or about 2 per cent, belong now to such associations and the number is increasing. Outside the Seventh Ward as large and probably a larger percentage belong to co-operative home-buying societies. The peculiar phenomenon among the colored people, however, is the wide development of beneficial and secret orders. Three hundred and six families, or 17 per cent of the Negroes of the ward, are reported as belonging to beneficial societies and probably 25 per cent or more actually belong. Beside these there are the petty insurance societies, to which 1021 families or 42 per cent belong. In more prosperous times this membership may reach 50 or 60 per cent or a total of at least 4000 men, women and children. The beneficial and secret societies, being organizations of Negroes, will be spoken of later. The petty insurance societies are for the most part conducted by whites. Some of these are reliable enterprises, and by careful management and honest dealing do something to encourage the saving spirit among the Negroes. It is doubtful, however, if they form the best kind of incentive, and probably they stand in the way of the savings-bank and building association. Only a few deserve this qualified approval. The large majority are little better than licensed gambling operations; it is a disgrace that a great municipality allows them to prey upon the people in the manner they do.14 They usually rest on no sound business principles; they take any and all risks, generally without medical examination and depend on lapses in payments and bold cheating to make money. Even the best conducted of these societies have to depend on the unreturned contributions of persons who cannot keep up their payments, to make both ends meet.

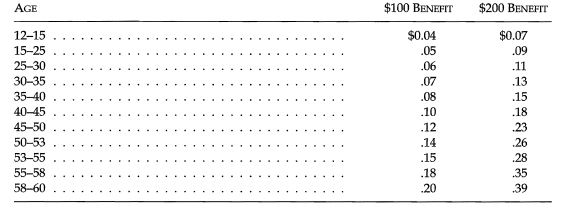

There were in 1897 thirty-one insurance societies doing business in the Seventh Ward. The following table gives the weekly premiums required for sick and death benefits in one society:

RATES AND DEATH BENEFITS

Weekly Dues for Benefits Payable at Death only

This is at the rate of $46.80 to $52 for a $1000 life policy at the age of 43, which can be had in regular companies for about $35. The excess represents the expense of collection and the gambler’s risk.

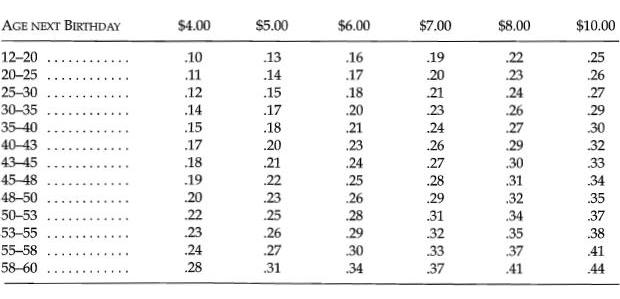

SICKNESS AND ACCIDENT BENEFITS

Weekly Dues for Specified Sums per Week

Amount payable to children after their certificates have been issued for the following periods:

Three months, one-third; six months, one-half; nine months, three-fourths; one year, full amount.

Death benefits, $40.

Weekly dues, 5 cents.

Upon payment of 10 cents weekly dues, children from six to eleven years will be paid weekly sick benefits of $2.50.

Membership fee for children, 50 cents.

Membership fee for adults, $1.

Into these companies a large part of the income of many families goes. For instance, let us examine the expenditures of certain actual families for such insurance, remembering that the total income of these families is in most cases $20 to $40 a month.

| MONTHLY | ||

| 1. | A family of 2 adults and 2 children (stevedore) | $3.29 |

| 2. | A family of 2 adults have for 10 years paid | 1.00 |

| 3. | A family of 4 adults | 2.20 |

| 4. | A family of 4 adults | 2.40 |

| 5. | A family of 1 adult and 1 child | 2.00 |

| 6. | A family of 4 adults | 1.84 |

| 7. | A family of 1 adult | $2.57 |

| 8. | A family of 2 adults (waiter) | 2.20 |

| 9. | A family of 2 adults (servant) | 1.50 |

| 10. | A family of 5 adults and 2 children (laborer) | 3.00 |

| 11. | A family of 2 adults and 3 children (stevedore) | 1.44 |

| 12. | A family of 9 adults and 1 child | 5.00 |

| 13. | A family of 8 adults and 4 children | 4.20 |

| 14. | A family of 9 adults | 4.43 |

| 15. | A family of 2 adults | 2.50 |

| 16. | A family of 2 adults (stevedore) | 3.00 |

| 17. | A family of 2 adults (stevedore) | 3.00 |

| 18. | A family of 10 adults | 8.50 |

| 19. | A family of 2 adults, 1 child (stevedore) | 5.00 |

| 20. | A family of 5 adults, child | 5.00 |

| 21. | A family of 3 adults | 3.90 |

| 22. | A family of 4 adults, 1 child (laborer) | 5.00 |

| 23. | A family of 2 adults, 3 children (waiter) | 4.60 |

It is impossible to get accurate returns as to the total amount spent by the Negroes of the Seventh Ward for insurance in such societies, but answers to questions on this point indicate a total expenditure of approximately $25,000 annually. For this enormous outlay something comes back in the benefits, but probably much less than half. The method of conducting these societies puts a premium on dishonesty and misrepresentation and a tax on honesty and health. A certain class of the insured get sick regularly and draw benefits and are winked at by the societies as a paying advertisement on the street. Their honest neighbors on the other hand will struggle on and work for years, paying regularly—in some cases five, ten and fifteen or more years in various societies—only to be cheated out of their insurance by rascally agents, or conniving home offices, or their own failure at the last moment to keep up payments. Of course the sum involved is too small, and the cheated persons too unknown and lowly to lead to litigation. Let us take some examples:15

In many other cases the matter of age is made a loophole for cheating; numbers of the Negroes do not know their exact ages; in such cases the insurance agent will suggest an age, usually below the evident truth, and insert it in the policy; if the insured dies the physician guesses at another age nearer the truth, and inserts it in the death certificate. Thereupon the insurance company points to the discrepancy, alleges an attempt to deceive on the part of the insured, and either refuses to pay any of the policy or generally offers to compound for a half or a third of the amount promised. This is perhaps the most common form of cheating outside the failure to account for the payments of lapsed members. In some cases the home office pays the death claim, and the local office or agent cheats the insured.

Without doubt such societies meet outrageous attempts at deception on the part of the insured; and yet since their methods of business put a premium on this sort of cheating they can hardly complain. The whole business is nothing more than gambling, where one set of sharpers bet against another set, and the honest hard-working but ignorant toilers pay the bill.16 With all the harm that open policy-playing and other sorts of gambling do, it is to be doubted if their effects on character are more deleterious than this form of insurance business. The Negroes by the crime of the Freedmen’s Bank have been long prejudiced against banks, and this business encourages their aversion to the slow, sure methods of saving. If the colored people are ever to learn “forehandedness,” in place of the slip-shod chance methods of living, the savings-bank must soon replace the insurance society; and that they could support savings-banks in abundance is shown by the fact that they annually invest between $75,000 and $100,000 in insurance societies in the city of Philadelphia.

It is not generally known how lucrative a business the exploitation of the Negro in various lines has become. In ornaments, clothes, entertainments, books and investment schemes, the shrewd and unscrupulous have a broad field of work, and it is being industriously cultivated, especially by whites and to some extent by certain classes of Negroes. Instead then of a struggling people being met by aid in the direction of their greatest weakness, they are surrounded by agencies which tend to make them more wasteful and dependent on chance than they are now. One has only to watch the pawn-brokers’ shops on Saturday night in winter to see how largely Negroes support them; and it is but a step from the insurance society to the pawnshop and thence to the policy shop.

30. Family Life—Among the masses of the Negro people in America the monogamic home is comparatively a new institution, not more than two or three generations old. The Africans were taken from polygamy and transplanted into a plantation where the home life was protected only by the caprice of the master, and practically unregulated polygamy and polyandry was the result, on the plantations of the West Indies. In States like Pennsylvania the marriage institution among slaves was early established and maintained. Consequently one meets among the Philadelphia Negroes the result of both systems—the looseness of plantation life and the strictness of Quaker teaching. Among the lowest class of recent immigrants and other unfortunates there is much sexual promiscuity and the absence of a real home life. Actual prostitution for gain is not as widespread as would at first thought seem natural. On the other hand, there are two widespread systems among the lowest classes, viz., temporary cohabitation and the support of men. Cohabitation of a more or less permanent character is a direct offshoot of the plantation life and is practiced considerably; in distinctly slum districts, like that at Seventh and Lombard, from 10 to 25 per cent of the unions are of this nature. Some of them are simply common-law marriages and are practically never broken. Others are compacts, which last for two to ten years; others for some months; in most of these cases the women are not prostitutes, but rather ignorant and loose. In such cases there is, of course, little home life, rather a sort of neighborhood life, centering in the alleys and on the sidewalks, where the children are educated. Of the great mass of Negroes this class forms a very small percentage and is absolutely without social standing. They are the dregs which indicate the former history and the dangerous tendencies of the masses. The system of supporting men is one common among the prostitutes of all countries, and widespread among the Negro women of the town. Two little colored girls walking along South street stopped before a gaudy pair of men’s shoes displayed in a shop window, and one said: “That’s the kind of shoes I’d buy my fellow!” The remark fixed their life history; they were from among the prostitutes of Middle Alley, or Ratcliffe street, or some similar resort, where each woman supports some man from the results of her gains. The majority of the well-dressed loafers whom one sees on Locust street near Ninth, on Lombard near Seventh and Seventeenth, on Twelfth near Kater, and in other such localities, are supported by prostitutes and political largesse, and spend their time in gambling. They are absolutely without home life, and form the most dangerous class in the community, both for crime and political corruption.

Leaving the slums and coming to the great mass of the Negro population we see undoubted effort has been made to establish homes. Two great hindrances, however, cause much mischief: the low wages of men and the high rents. The low wages of men make it necessary for mothers to work and in numbers of cases to work away from home several days in the week. This leaves the children without guidance or restraint for the better part of the day—a thing disastrous to manners and morals. To this must be added the result of high rents, namely, the lodging system. Whoever wishes to live in the centre of Negro population, near the great churches and near work, must pay high rent for a decent house. This rent the average Negro family cannot afford, and to get the house they sub-rent a part to lodgers. As a consequence, 38 per cent of the homes of the Seventh Ward have unknown strangers admitted freely into their doors. The result is, on the whole, pernicious, especially where there are growing children. Moreover, the tiny Philadelphia houses are ill suited to a lodging system. The lodgers are often waiters, who are at home between meals, at the very hours when the housewife is off at work, and growing daughters are thus left unprotected. In some cases, though this is less often, servant girls and other female lodgers are taken. In such ways the privacy and intimacy of home life is destroyed, and elements of danger and demoralization admitted. Many families see this and refuse to take lodgers, and move where they can afford the rent without help. This involves more deprivations to a socially ostracized race like the Negro than to whites, since it often means hostile neighbors or no social intercourse. If a number of Negroes settle together, the real estate agents dump undesirable elements among them, which some enthusiastic association has driven from the slums.

There are a large number of waiters, porters and servant girls in the city who naturally have no home life and are exposed to peculiar temptations. The church is the rallying place of the best class of these young people, and it attempts to furnish their amusements. Loafing and promenading the streets is the only other entertainment most of these young folks have. They form a serious problem, to which the lodging system is the only attempted answer, and that a dangerous one. Homes and clubs properly conducted ought to be opened for them. A Young Men’s Christian Association which would not degenerate into an endless prayer meeting might meet the wants of the young men.

The home life of the middle laboring class lacks many of the pleasant features of good homes. Traces of plantation customs still persist, and there is a widespread custom of seeking amusement outside the home; thus the home becomes a place for a hurried meal now and then, and lodging. Only on Sundays does the general gathering in the front room, the visits and leisurely dinner, smack of proper home life. Nevertheless, the spirit of home life is steadily growing. Nearly all the housewives deplore the lodging system and the work that keeps them away from home; and there is a widespread desire to remedy these evils and the other evil which is akin to them, the allowing of children and young women to be out unattended at night.

In the better class families there is a pleasant family life of distinctly Quaker characteristics. One can go into such homes in the Seventh Ward and find all the quiet comfort and simple good-hearted fare that one would expect among well-bred people. In some cases the homes are lavishly furnished, in others they are homely and old-fashioned. Even in the best homes, however, there is easily detected a tendency to let the communal church and society life trespass upon the home. There are fewer strictly family gatherings than would be desirable, fewer simple neighborhood gatherings and visits; in their place are the church teas, the hall concerts, or the elaborate parties given by the richer and more ostentatious. These things are of no particular moment to the circle of families involved, but they set an example to the masses which may be misleading. The mass of the Negro people must be taught sacredly to guard the home, to make it the centre of social life and moral guardianship. This it is largely among the best class of Negroes, but it might be made even more conspicuously so than it is. Such emphasis undoubtedly means the decreased influence of the Negro church, and that is a desirable thing.

On the whole, the Negro has few family festivals; birthdays are not often noticed, Christmas is a time of church and general entertainments, Thanksgiving is coming to be widely celebrated, but here again in churches as much as in homes. The home was destroyed by slavery, struggled up after emancipation, and is again not exactly threatened, but neglected in the life of city Negroes. Herein lies food for thought.