1. Michael B. Katz and Thomas J. Sugrue, “The Context of The Philadelphia Negro: The City, the Settlement House Movement, and the Rise of the Social Sciences,” in W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and the City: “The Philadelphia Negro” and Its Legacy, edited by Michael B. Katz and Thomas J. Sugrue (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), p. 26.

2. Elliot Rudwick, “Note on a Forgotten Black Sociologist: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Sociological Profession,” American Sociologist 4 (1969): 303–306; Dan S. Green and Edwin D. Driver, “W. E. B. Du Bois: A Case in the Sociology of Sociological Negation,” Phylon 37 (1976): 308–333; and R. Charles Key, “Society and Sociology: The Dynamics of Black Sociological Negation,” Phylon 39 (1978): 35–48.

3. Quoted in David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868–1919 (New York: Holt, 1993), p. 188.

4. Martin Bulmer, “W. E. B. Du Bois as a Social Investigator: The Philadelphia Negro, 1899,” in The Social Survey in Historical Perspective, 1880–1940, edited by Martin Bulmer, Kevin Bales, and Kathryn Kish Sklar (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pp. 170–188.

5. Mia Bay, “ ‘The World Was Thinking Wrong about Race’: The Philadelphia Negro and Nineteenth-Century Science,” in W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and the City: “The Philadelphia Negro” and Its Legacy, edited by Michael B. Katz and Thomas J. Sugrue (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), pp. 41–60.

6. Jacqueline Jones, “ ‘Lifework’ and Its Limits: The Problem of Labor in The Philadelphia Negro,” in W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and the City: “The Philadelphia Negro” and Its Legacy, edited by Michael B. Katz and Thomas J. Sugrue (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1998), and Alice O’Connor, Poverty Knowledge: Social Science, Social Policy, and the Poor in Twentieth-Century U.S. History (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2001).

7. See essays in Obie Clayton, Ronald B. Mincy, and David Blankenhorn, editors, Black Fathers in Contemporary American Society: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Strategies for Change (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2003).

8. Mary Patillo, “Black Middle Class Neighborhoods,” Annual Review of Sociology 31 (2005): 305–329.

9. Omar M. McRoberts, Streets of Glory: Church and Community in a Black Urban Neighborhood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

10. Lawrence D. Bobo, “Reclaiming a Du Boisian Perspective on Racial Attitudes,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 568 (2000): 186–202.

11. Alford A. Young, The Minds of Marginalized Black Men: Making Sense of Mobility, Opportunity, and Future Life Chances (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004).

12. Michael C. Dawson, Black Visions: The Roots of Contemporary African-American Political Ideologies (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); Melissa Victoria Harris-Lacewell, Barbershops, Bibles, and BET: Everyday Talk and Black Political Thought (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2004).

13. Howard Winant, “Race and Race Theory,” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000): 169–185, and Tukufu Zuberi, Thicker Than Blood: How Racial Statistics Lie (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

14. George M. Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind: The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817–1914 (New York: Harper and Row, 1971), and Jonathan H. Turner and Royce Singleton, “A Theory of Ethnic Oppression: Toward a Reintegration of Cultural and Structural Concepts in Ethnic Relations Theory,” Social Forces 56 (1978): 1001–1018.

15. W. E. B. Du Bois, “The Study of Negro Problems,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 11 (1898): 1–23.

1. I shall throughout this study use the term “Negro,” to designate all persons of Negro descent, although the appellation is to some extent illogical. I shall, moreover, capitalize the word, because I believe that eight million Americans are entitled to a capital letter.

2. See Appendix A for form of schedules used.

3. The appended study of domestic service was done by Miss Isabel Eaton, Fellow of the College Settlements Association. Outside of this the work was done by the one investigator.

1. Cf. Scharf-Westcott’s “History of Philadelphia,” I, 65, 76. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 24.

2. Hazard’s “Annals,” 553. Thomas’ “Attitude of Friends Toward Slavery,” 266.

3. There is some controversy as to whether these Germans were actually Friends or not; the weight of testimony seems to be that they were. See, however, Thomas as above, p. 267, and Appendix. “Pennsylvania Magazine,” IV, 28–31; The Critic, August 27, 1897. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 20, 203. For copy of protest, see published fac-simile and Appendix of Thomas. For further proceedings of Quakers, see Thomas and DuBois, passim.

4. “Colonial Records,” I, 380–81.

5. Thomas, 276; Whittier Intro. to Woolman, 16.

6. See Appendix B.

7. “Statutes-at-Large,” Ch. 143, 881. See Appendix B.

8. “Statutes-at-Large,” III, pp. 250, 254; IV, 59 ff. See Appendix B.

9. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 23, note. U. S. Census.

10. See Appendix B. Cf. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” passim.

11. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 206.

12. Scharf-Westcott’s “History of Philadelphia,” 1,200.

13. Watson’s “Annals,” (Ed. 1850) 1, 98.

14. See Appendix B.

15. Cf. Chapter XIII.

16. “Colonial Records,” VIII, 576; DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 23.

17. Cf. Pamphlet: “Sketch of the Schools for Blacks,” also Chapter VIII.

18. Cf. Thomas’ “Attitude of Friends,” etc., p. 272.

19. Dallas’ “Laws,” 1, 838, Ch. 881; DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 225.

20. Cf. Watson’s “Annals” (Ed. 1850), 1, 557, 101–103, 601, 602, 515.

21. The American Museum, 1789, pp. 61–62.

22. For life of Allen, see his “Autobiography,” and Payne’s “History of the A. M. E. Church.”

23. For life of Jones, see Douglass’ “Episcopal Church of St. Thomas.”

24. The testimonial was dated January 23, 1794, and was as follows: “Having, during the prevalence of the late malignant disorder, had almost daily opportunities of seeing the conduct of Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, and the people employed by them to bury the dead, I, with cheerfulness give this testimony of my approbation of their proceedings as far as the same came under my notice. Their diligence, attention and decency of deportment, afforded me at the time much satisfaction.

WILLIAM CLARKSON, Mayor.”

From Douglass’ “St. Thomas’ Church.”

26. See Allen’s “Autobiography,” and Douglass’ “St. Thomas.’ ”

27. Douglass’ “St. Thomas.’ ”

28. There is on the part of the A. M. E. Church a disposition to ignore Allen’s withdrawal from the Free African Society, and to date the A. M. E. Church from the founding of that society, making it older than St. Thomas. This, however, is contrary to Allen’s own statement in his “Autobiography.” The point, however, is of little real consequence.

29. Carey & Bioren, Ch. 394. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” p. 231.

30. The constitution, as reported, had the word “white,” but this was struck out at the instance of Gallatin. Cf. Ch. XVII.

31. Cf. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” Chapter VII.

32. “Annals of Congress,” 6 Cong., I Sess., pp. 229–45. DuBois’ “Slave Trade,” pp. 81–83.

33. Quoted by W. C. Bolivar in Philadelphia Tribune.

34. Delany’s “Colored People,” p. 74.

35. Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser, July 4, 1791. William White had a large commission-house on the wharves about this time. Considerable praise is given the Insurance Society of 1796 for its good management. Cf. “History of the Insurance Companies of North America.” In 1817 the first convention of Free Negroes was held here, through the efforts of Jones and Forten.

1. These laws were especially directed against kidnapping, and were designed to protect free Negroes. See Appendix B. The law of 1826 was declared unconstitutional in 1842 by the U. S. Supreme Court. See 16 Peters, 500 ff.

2. A meeting of Negroes held in 1822, at the A. M. E. Church, denounced crime and Negro criminals.

3. Scharf-Westcott’s “History of Philadelphia,” I, 824. There was at this time much lawlessness in the city which had no connection with the presence of Negroes, and which led to rioting and disorder in general. Cf. Price’s “History of Consolidation.”

4. Southampton was the scene of the celebrated Nat Turner insurrection of Negroes.

5. Letter to Nathan Mendelhall, of North Carolina.

6. Hazard’s “Register,” XIV, 126–28, 200–203.

7. Ibid., XVI. 35–38.

8. Scharf-Westcott’s “Philadelphia,” I, 654–55.

9. Price, “History of Consolidation,” etc., Ch. VII. The county eventually paid $22,658.27, with interest and costs, for the destruction of the hall.

10. Scharf-Westcott, I, 660–61.

11. Case of Fogg vs. Hobbs, 6 Watts, 553–560. See Chapter XII.

12. See Chapter XII and Appendix B.

13. Appeal of 40,000 citizens, etc., Philadelphia, 1838. Written chiefly by the late Robert Purvis, son-in-law of James Forten.

14. See Minutes of Conventions; the school was to be situated in New Haven, but the New Haven authorities, by town meeting, protested so vehemently that the project had to be given up. Cf. also Hazard, V, 143.

15. Hazard’s “Register,” IX, 361–62.

16. Biddle’s “Ode to Bogle,” is a well-known squib; Bogle himself is credited with considerable wit. “You are of the people who walk in darkness,” said a prominent clergyman to him once in a dimly lighted hall. “But,” replied Bogle, bowing to the distinguished gentleman, “I have seen a great light.”

17. See in Philadelphia Times, October 17, 1896, the following notes by “Megargee:” Dorsey was one of the triumvirate of colored caterers—the other two being Henry Jones and Henry Minton—who some years ago might have been said to rule the social world of Philadelphia through its stomach. Time was when lobster salad, chicken croquettes, deviled crabs and terrapin composed the edible display at every big Philadelphia gathering, and none of those dishes were thought to be perfectly prepared unless they came from the hands of one of the three men named. Without making any invidious comparisons between those who were such masters of the gastronomic art, it can fairly be said that outside of his kitchen, Thomas J. Dorsey outranked the others. Although without schooling, he possessed a naturally refined instinct that led him to surround himself with both men and things of an elevating character. It was his proudest boast that at his table, in his Locust street residence, there had sat Charles Sumner, William Lloyd Garrison, John W. Forney, William D. Kelley and Fred Douglass.… Yet Thomas Dorsey had been a slave; had been held in bondage by a Maryland planter. Nor did he escape from his fetters until he had reached a man’s estate. He fled to this city, but was apprehended and returned to his master. During his brief stay in Philadelphia, however, he made friends, and these raised a fund of sufficient proportion to purchase his freedom. As a caterer he quickly achieved both fame and fortune. His experience of the horrors of slavery had instilled him with an undying reverence for those champions of his down-trodden race, the old-time Abolitionists. He took a prominent part in all efforts to elevate his people, and in that way he came in close contact with Sumner, Garrison, Forney and others.

18. Henry Jones was in the catering business thirty years, and died September 24, 1875, leaving a considerable estate.

19. Henry Minton came from Nansemond County, Virginia, at the age of nineteen, arriving in Philadelphia in 1830. He was first apprenticed to a shoemaker, then went into a hotel as waiter. Finally he opened dining rooms at Fourth and Chestnut. He died March 20, 1883.

20. This band was in great demand at social functions, and its leader received a trumpet from Queen Victoria.

21. See Spiers’ “Street Railway System of Philadelphia,” pp. 23–27; also unpublished MS. of Mr. Bernheimer, on file among the senior theses in the Wharton School of Finance and Economy, University of Pennsylvania.

22. Pamphlet on “Enlistment of Negro Troops,” Philadelphia Library.

23. Cf. Scharf-Westcott, I, 837.

24. The following account of an eye-witness, Mr. W. C. Bolivar, is from the Philadelphia Tribune, a Negro paper: “In the spring election preceding the murder of Octavius V. Catto, there was a good deal of rioting. It was at this election that the United States Marines were brought into play under the command of Col. James Forney. Their very presence had the salutary effect of preserving order. The handwriting of political disaster to the Democratic party was plainly noticed. This galled ‘the unterrified,’ and much of the rancor was owing to the fact that the Negro vote would guarantee Republican supremacy beyond a doubt. Even then Catto had a narrow escape through a bullet shot at Michael Maher, an ardent Republican, whose place of business was at Eighth and Lombard streets. This assault was instigated by Dr. Gilbert, whose paid or coerced hirelings did his bidding. The Mayor, D. M. Fox, was a mild, easygoing Democrat, who seemed a puppet in the hands of astute conscienceless men. The night prior to the day in question, October 10, 1871, a colored man named Gordon was shot down in cold blood on Eighth street. The spirit of mobocracy filled the air, and the object of its spleen seemed to have been the colored men. A cigar store kept by Morris Brown, Jr., was the resort of the Pythian and Banneker members, and it was at this place on the night prior to the murder that Catto appeared among his old friends for the last time. When the hour arrived for home going, Catto went the near and dangerous way to his residence, 814 South street, and said as he left, ‘I would not stultify my manhood by going to my home in a roundabout way.’ When he reached his residence he found one of its dwellers had his hat taken from him at a point around the corner. He went out and into one of the worst places in the Fourth Ward and secured it.

“Intimidation and assault began with the opening of the polls. The first victim was Levi Bolden, a playfellow, as a boy, with the chronicler of these notes. Whenever they could conveniently catch a colored man they forthwith proceeded to assail him. Later in the day a crowd forced itself into Emeline street and battered in the brains of Isaac Chase, going into his home, wreaking their spite on this defenceless man, in the presence of his family. The police force was Democratic, and not only stood idly by, but gave practical support. They took pains to keep that part of the city not in the bailiwick of the rioters from knowing anything of what was transpiring. Catto voted and went to school, but dismissed it after realizing the danger of keeping it open during the usual hours. Somewhere near 3 o’clock as he neared his dwelling, two or three men were seen to approach him from the rear, and one of them, supposed to have been either Frank Kelly or Reddy Dever, pulled out a pistol and pointed it at Catto. The aim of the man was sure, and Catto barely got around a street car before he fell. This occurred directly in front of a police station, into which he was carried. The news spread in every direction. The wildest excitement prevailed, and not only colored men, but those with the spirit of fair play, realized the gravity of the situation, with a divided sentiment as to whether they ought to make an assault on the Fourth Ward or take steps to preserve the peace. The latter prevailed, and the scenes of carnage, but a few hours back, when turbulence was supreme, settled down to an opposite state of almost painful calmness. The rioting during that day was in parts of the Fifth, Seventh and Fourth wards, whose boundary lines met. It must not be supposed that the colored people were passive when attacked, because the records show’ an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,’ in every instance. No pen is graphic enough to detail the horrors of that day. Each home was in sorrow, and strong men wept like children, when they realized how much had been lost in the untimely death of the gifted Catto.

“Men who had sat quietly unmindful of things not directly concerning themselves, were aroused to the gravity of the situation, wrought by the spirit of a mob, came out of their seclusion and took a stand for law and order. It was a righteous public sentiment that brought brute force to bay. The journals not only here, but the country over, with one voice condemned the lawless acts of October 10, 1871. Sympathetic public gatherings were held in many cities, with the keynote of condemnation as the only true one. Here in Philadelphia a meeting of citizens was held, from which grew the greater, held in National Hall, on Market street, below Thirteenth. The importance of this gathering is shown by a list its promoters. Samuel Perkins, Esq., called it to order, and the eminent Hon. Henry C. Carey presided. Among some of those in the list of vice-presidents were Hon. William M. Meredith, Gustavus S. Benson, Alex. Biddle, Joseph Harrison, George H. Stuart, J. Effingham Fell, George H. Boker, Morton McMichael, James L. Claghorn, F. C. and Benjamin H. Brewster, Thomas H. Powers, Hamilton Disston, William B. Mann, John W. Forney, John Price Wetherill, R. L. Ashhurst, William H. Kemble, William S. Stokley, Judge Mitchell, Generals Collis and Sickel, Congressmen Kelley, Harmer, Myers, Creely, O’Neill, Samuel H. Bell and hundreds more. These names represented the wealth, brains and moral excellence of this community. John Goforth, the eminent lawyer, read the resolutions, which were seconded in speeches by Hon. William B. Mann, Robert Purvis, Isaiah C. Weirs, Rev. J. Walker Jackson, Gen. C. H. T. Collis and Hon. Alex. K. McClure. These all breathed the same spirit, the condemnation of mob law and a demand for equal and exact justice to all. The speech of Col. McClure stands out boldly among the greatest forensic efforts ever known to our city. His central thought was ‘the unwritten law,’ which made an impression beyond my power to convey. In the meanwhile, smaller meetings were held in all parts of the city to record their earnest protest against the brute force of the day before. That was the end of disorder in a large scale here. On the sixteenth of October the funeral occurred. The body lay in state at the armory of the First Regiment, Broad and Race streets, and was guarded by the military. Not since the funeral cortege of President Lincoln had there been one as large or as imposing in Philadelphia. Outside of the Third Brigade, N. G. P., detached commands from the First Division, and the military from New Jersey, there were civic organizations by the hundreds from Philadelphia, to say nothing of various bodies from Washington, Baltimore, Wilmington, New York and adjacent places. All the city offices were closed, beside many schools. City Councils attended in a body, the State Legislature was present, all the city employees marched in line, and personal friends came from far and near to testify their practical sympathy. The military was under the command of General Louis Wagner, and the civic bodies marshaled by Robert M. Adger. The pall-bearers were Lieutenant Colonel Ira D. Cliff, Majors John W. Simpson and James H. Grocker, Captains J. F. Needham and R. J. Burr, Lieutenants J. W. Diton, W. W. Morris and Dr. E. C. Howard, Major and Surgeon of the Twelfth Regiment. This is but a mere glance backward at the trying days of October, 1871, and is written to refresh the minds of men and women of that day, as well as to chronicle a bit of sad history that this generation may be informed. And so closed the career of a man of splendid equipment, rare force of character, whose life was so interwoven with all that was good about us, as to make it stand out in bold relief, as a pattern for those who have followed after.”

25. Cf. Appendix B.

26. See Appendix C. The inquiry of 1838 was by the Philadelphia Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery, and the report was in two parts, one a register of trades and one a general report of forty pages. The Society of Friends, or the Abolition Society, undertook the inquiry of 1849, and published a pamphlet of forty-four pages. There was also the same year a report on the health of colored convicts. A pamphlet by Edward Needles was also published in 1849, comparing the Negroes in 1837 and 1848. Benjamin C. Bacon, at the instance of the Abolition Society, made the inquiry in 1856, which was published that year. In 1859, a second edition was issued with criminal statistics. All these pamphlets may be consulted at the Library Company of Philadelphia, or the Ridgway branch.

1. The unit for study throughout this essay has been made the county of Philadelphia, and not the city, except where the city is especially mentioned. Since 1854, the city and county have been coterminous. Even before that the population of the “districts” was for our purposes an urban population, and a part of the group life of Philadelphia.

2. My attention was first called to this fact by Professor Kelly Miller, of Howard University; cf. “Publications of American Negro Academy,” No.1. There is probably, in taking censuses, a larger percentage of omissions among males than among females; such omissions would, however, go but a small way toward explaining this excess of females.

3. In a good many of the Eleventh Census tables, “Chinese, Japanese and civilized Indians,” were very unwisely included in the total of the Colored, making an error to be allowed for when one studies the Negro. In most cases the discrepancy can be ignored. In this case this fact but serves to decrease the excess of females, as these other groups have an excess of males. The city of Philadelphia has 1003 Chinese, Japanese and Indians. The figures for the whole United States show that this excess of females is probably confined to cities:

NEGROES ACCORDING TO SEX

| SECTION | MALES | FEMALES |

| United States | 3,725,561 | 3,744,479 |

| North Atlantic | 133,277 | 136,629 |

| South Atlantic | 1,613,769 | 1,648,921 |

| North Central | 222,384 | 208,728 |

| South Central | 1,739,565 | 1,739,686 |

| Western | 16,566 | 10,515 |

4. Figures for other years have not been found.

5. In social gatherings, in the churches, etc., men are always at a premium, and this very often leads to lowering the standard of admission to certain circles, and often gives one the impression that the social level of the women is higher than the level of the men.

6. The age groupings in these tables are necessarily unsatisfactory on account of the vagaries of the census.

7. “In the Fifth Ward only there are 171 small streets and courts; Fourth Ward, 88. Between Fifth and Sixth, South and Lombard streets, 15 courts and alleys.” “First Annual Report College Settlement Kitchen.” p. 6.

8. In a residence of eleven months in the centre of the slums, I never was once accosted or insulted. The ladies of the College Settlement report similar experience. I have seen, however, some strangers here roughly handled.

9. It is often asked why do so many Negroes persist in living in the slums. The answer is, they do not; the slum is continually scaling off emigrants for other sections, and receiving new accretions from without. Thus the efforts for social betterment put forth here have often their best results elsewhere, since the beneficiaries move away and others fill their places. There is, of course, a permanent nucleus of inhabitants, and these, in some cases, are really respectable and decent people. The forces that keep such a class in the slums are discussed further on.

10. Gulielma street, for instance, is a notorious nest for bad characters, with only one or two respectable families.

11. The almost universal and unsolicited testimony of better class Negroes was that the attempted clearing out of the slums of the Fifth Ward acted disastrously upon them; the prostitutes and gamblers emigrated to respectable Negro residence districts, and real estate agents, on the theory that all Negroes belong to the same general class, rented them houses. Streets like Rodman and Juniper were nearly ruined, and property which the thrifty Negroes had bought here greatly depreciated. It is not well to clean a cess-pool until one knows where the refuse can be disposed of without general harm.

12. The majority of these were brothels. A few, however, were homes of respectable people who resented the investigation as unwarranted and unnecessary.

13. Twenty-nine women and four men. The question of race intermarriage is discussed in Chapter XIV.

14. There may have been some duplication in the counting of servant girls who do not lodge where they work. Special pains was taken to count them only where they lodge, but there must have been some errors. Again, the Seventh Ward has a very large number of lodgers; some of these form a sort of floating population, and here were omissions; some were forgotten by landladies and others purposely omitted.

15. There is a wide margin of error in the matter of Negroes’ ages, especially of those above fifty; even of those from thirty-five to fifty, the age is often unrecorded and is a matter of memory, and poor memory at that. Much pains was taken during the canvass to correct errors and to throw out obviously incorrect answers. The error in the ages under forty is probably not large enough to invalidate the general conclusions; those under thirty are as correct as is general in such statistics, although the ages of children under ten is liable to err a year or so from the truth. Many women have probably understated their ages and somewhat swelled the period of the thirties as against the forties. The ages over fifty have a large element of error.

1. There are many sources of error in these returns: it was found that widows usually at first answered the question “Are you married?” in the negative, and the truth had to be ascertained by a second question; unfortunate women and questionable characters generally reported themselves as married; divorced or separated persons called themselves widowed. Such of these errors as were made through misapprehension, were often corrected by additional questions; in case of designed deception the answer was naturally thrown out if the deception was detected, which of course happened in few cases. The net result of these errors is difficult to ascertain: certainly they increase the apparent number of the truly widowed to some extent at the expense of the single and married.

2. The number of actually divorced persons among the Negroes is naturally insignificant; on the other hand the permanent separations are large in number and an attempt has been made to count them. They do not exactly correspond to the divorce column of ordinary statistics and therefore take something from the married column. The number of widowed is probably exaggerated somewhat, but even allowing for errors, the true figure is high. The markedly higher death rate for males has much to do with this. Cf. Chapter X.

3. Unfortunately Philadelphia has no reliable registration of births, and the illegitimate birth rate of Negroes cannot be ascertained. This is probably high judging from other conditions.

4. And, to tell the truth, contact with some very unsavory phases of it.

5. There can be no doubt but what sexual looseness is to-day the prevailing sin of the mass of the Negro population, and that its prevalence can be traced to bad home life in most cases. Children are allowed on the street night and day unattended; loose talk is often indulged in; the sin is seldom if ever denounced in the churches. The same freedom is allowed the poorly trained colored girl as the white girl who has come through a strict home, and the result is that the colored girl more often falls. Nothing but strict home life can avail in such cases. Of course there is much to be said in palliation: the Negress is not respected by men as white girls are, and consequently has no such general social protection; as a servant, maid, etc., she has peculiar temptations; especially the whole tendency of the situation of the Negro is to kill his self-respect which is the greatest safeguard of female chastity.

1. The chief source of error in the returns as to birthplace are the answers of those who do not desire to report their birthplace as in the South. Naturally there is considerable social distinction between recently arrived Southerners and old Philadelphians; consequently the tendency is to give a Northern birthplace. For this reason it is probable that even a smaller number than the few reported were really born in the city.

2. Compare “The Negroes of Farmville: A Social Study,” in Bulletin of U. S. Labor Bureau, January, 1898.

3. In the case of lodgers not at home and sometimes of members of families answers could not be obtained to this question. There were in all 862 persons born outside the city from whom answers were not obtained.

4. Absalom Jones, Dorsey, Minton, Henry Jones and Augustin were none of them natives of Philadelphia.

5. Chinese, Japanese and Indians are included in these tables. The exact figures are:

| Negro population of Pennsylvania | 107,626 |

| Of these, born in Pennsylvania | 58,681 |

| Virginia | 19,873 |

| Maryland | 12,202 |

| Delaware | 4,851 |

| New Jersey | 1,786 |

| New York | 891 |

| North Carolina | 1,362 |

| District Columbia | 1,131 |

| Unknown | 1,804 |

1. This account is mainly from the pamphlet: “A Brief Sketch of the Schools for Black People,” etc. Philadelphia, 1867.

2. Within a few years a Negro had to fight his way through a prominent dental college in the city.

3. Philadelphia Ledger, August 13, 1897.

4. The chief error in the school returns arises from irregularity in attendance. Those reported in school were there sometime during the year, and possibly off and on during the whole year, but many were not steady attendants.

5. Of 647 school children 62 were in school less than nine months—some less than three. Probably many more than this did not attend the full term.

6. As has before been noted, the Negroes are less apt to deceive deliberately than some other peoples. The ability to read, however, is a point of pride with them, and especial pains was taken in the canvass to avoid error; often two or more questions on the point were asked. Nevertheless all depended in the main on voluntary answers.

7. This looks small and yet it probably approximates the truth. My general impression from talking with several thousand Negroes in the Seventh Ward is that the percentage of total illiteracy is small among them.

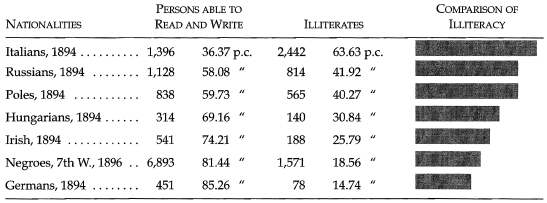

8. The Seventh Special Report of the United States Commissioner of Labor enables us to make some comparison of the illiteracy of the foreign and Negro populations of the City:

The foreigners here reported include all those living in certain parts of the Third and Fourth Wards of Philadelphia. They are largely recent immigrants. The Russians and Poles are mostly Jews.—ISABEL EATON.

9. Data furnished by two principals of colored schools. At present (1897) there are 58 Negro students in the following schools: Central High, Girls’ Normal, Girls’ High, Central Manual Training and North East Manual Training; or about one per cent of the total school enrollment.

10. Probably the percentage of children promoted from primary to grammar grades in this case is unusually small.

11. The following report from a member of the Committee on Schools of the City Councils is taken from the Philadelphia Ledger, December 2, 1896: On the matter of the needs of the colored population in connection with the schools, Mr. Meehan had to say: “Young women of the colored race are qualifying themselves for public school teachers by taking the regular course through our Normal School. No matter how well qualified they may be to teach, directors do not elect them to positions in the schools. It is taken for granted that only white teachers shall be placed in charge of white children. The colored Normal School graduates might be given a chance by appointments in the centre of some colored population, so that colored people might support their own teachers if so disposed, as they support their own ministers in their separate colored churches. The good result of this arrangement is shown by the experience in the Twenty-second Section, where there are two schools with seven colored teachers, ranking among the most popular in the section.”

12. Negroes in the city raised $2000 toward this.

1. The returns as to occupations are on the whole reliable. There was in the first place little room for deception, since the occupations of Negroes are so limited that a false or indefinite answer was easily revealed by a little judicious probing; moreover there was little disposition to deceive, for the Negroes are very anxious to have their limited opportunities for employment known; thus the motives of pride and complaint balanced each other fairly well. Some error of course remains: the number of servants and day workers is slightly understated; the number of caterers and men with trades is somewhat exaggerated by the answers of men with two occupations: e.g., a waiter with a small side business of catering returns himself as caterer; a carpenter who gets little work and makes his living largely as a laborer is sometimes returned as a carpenter, etc. In the main the errors are small and of little consequence.

2. A more detailed list of the occupations of male Negroes, twenty-one years of age and over, living in the Seventh Ward in 1896, is as follows:

ENTREPRENEURS

| Caterers | 65 |

| Hucksters | 37 |

| Proprietors Hotels and Restaurants | 22 |

| Merchants: Fuel and Notions | 22 |

| Proprietors of Barber Shops | 15 |

| Expressmen owning outfit | 14 |

| Merchants, Cigar Stores | 7 |

| Merchants, Grocery Stores | 4 |

| Proprietors of Undertaking Establishments | 2 |

| Employment Agents | 3 |

| Lodging House Keepers | 3 |

| Proprietors of Pool Rooms | 3 |

| Real Estate Agencies | 3 |

| Job Printers | 1 |

| Builder and Contractor | 1 |

| Sub-landlord | 1 |

| Milk Dealer | 1 |

| Publisher | 207 |

| Clergymen | 22 |

| Students | 17 |

| Teachers | 7 |

| Physicians | 6 |

| Lawyers | 5 |

| Dentists | 3 |

| Editors | 1 |

| 61 |

IN THE SKILLED TRADES

| Barbers | 64 |

| Cigar Makers | 39 |

| Shoemakers | 18 |

| Stationary Engineers | 13 |

| Bricklayers | 11 |

| Printers | 10 |

| Painters | 10 |

| Upholsterers | 7 |

| Carpenters | 6 |

| Bakers | 4 |

| Tailors | 4 |

| Undertakers | 4 |

| Brickmakers | 3 |

| Framemakers | 3 |

| Plasterers | 3 |

| Rubber Workers | 3 |

| Stone Cutters | 3 |

| Bookbinders | 2 |

| Candy | 2 |

| Chiropodists | 2 |

| Ice Carvers | 2 |

| Photographers | 2 |

| Apprentice | 1 |

| Boilermaker | 1 |

| Blacksmit | 1 |

| China Repairer | 1 |

| Cooper | 1 |

| Cabinetmaker | 1 |

| Dyer | 1 |

| Furniture Polisher | 1 |

| Gold Beater | 1 |

| Kalsominer | 1 |

| Locksmith | 1 |

| Laundryman (steam) | 1 |

| Paper Hanger | 1 |

| Roofer | 1 |

| Tinsmith | 1 |

| Wicker Worker | 1 |

| Horse Trainer | 1 |

| Chemist | 1 |

| Florist | 1 |

| Pilot | 1 |

| 236 |

CLERKS, SEMI-PROFESSIONAL AND RESPONSIBLE WORKERS

| Messengers | 33 |

| Stewards | 31 |

| Musicians | 20 |

| Clerks | 18 |

| Agents | 15 |

| Clerks in Public Service | 8 |

| Managers and Foremen | 6 |

| Actors | 6 |

| Bartenders | 5 |

| Policemen | 5 |

| Sextons | 4 |

| Shipping Clerks | 3 |

| Dancing Masters | 3 |

| Inspector in Factory | 1 |

| Cashier | 1 |

| 159 |

SERVANTS

| Domestics | 582 |

| Hotel Help | 457 |

| Public Waiters | 38 |

| Nurses | 2 |

| 1,079 |

| Stevedores | 164 |

| Teamsters | 134 |

| Janitors | 94 |

| Hod Carriers | 79 |

| Hostlers | 44 |

| Elevator Men | 22 |

| Sailors | 21 |

| China Packers | 14 |

| Watchmen | 14 |

| Drivers | 12 |

| Oyster Openers | 4 |

| 602 |

LABORERS (ORDINARY)

| Common Laborers | 493 |

| Porters | 274 |

| Laborers for City | 47 |

| Bootblacks | 22 |

| Casual Laborers | 12 |

| Miscellaneous Laborers | 4 |

| 852 |

MISCELLANEOUS

| Rag Pickers | 6 |

| “Politicians” | 2 |

| Root Doctors | 2 |

| Prize Fighter | 1 |

| 11 |

3. This includes 12 housewives who also work.

4. A more detailed list of the occupations of female Negroes, twenty-one years of age and over, living in the Seventh Ward in 1896, is as follows:

ENTREPRENEURS

| Caterers | 18 |

| Restaurant Keepers | 17 |

| Merchants | 17 |

| Employment Agents | 5 |

| Undertakers | 3 |

| Child-Nursery Keepers | 3 |

| 63 |

LEARNED PROFESSIONS

| Teachers | 22 |

| Trained Nurses | 8 |

| Students | 7 |

| 37 |

SKILLED TRADES

| Dressmakers | 204 |

| Hairdressers | 6 |

| Milliners | 3 |

| Shrouders of Dead | 4 |

| Apprentice | 1 |

| Manicure | 1 |

| Barber | 1 |

| Typesetter | 1 |

| 221 |

CLERKS, SEMI-PROFESSIONAL AND RESPONSIBLE WORKERS

| Musicians | 12 |

| Clerks | 10 |

| Stewardesses | 4 |

| Housekeepers | 4 |

| Agents | 3 |

| Stenographers | 3 |

| Matrons | 2 |

| Actress | 1 |

| Missionary | 1 |

| 40 |

| Housewives and Day Workers | 937 |

| Day Workers | 128 |

| Public Cooks | 72 |

| Seamstresses | 48 |

| Waitresses in Restaurants, etc. | 14 |

| Janitresses | 22 |

| Factory Employee | 1 |

| Office Maids | 12 |

| 1,234 |

SERVANTS

| Domestic Servants | 1,262 |

5. A better comparison here would be made by finding the percentages of the population above 10 years of age; statistics unfortunately are not available for this.

6. This has been the case only in comparatively recent times.

7. Negroes also buy immense quantities of patent medicines, etc.

8. In Norfolk, Va., I once saw the advertisement on a street sign calling for colored “clerks, saleswomen, stenographers,” etc., for Northern cities!

9. This total includes a large number of men and women who do some private catering, but for the most part work under other caterers; strictly a large part of them are waiters rather than caterers.

10. Mr. Stevens died in 1898—he was an honest, reliable, business man—of pleasant address, and universally respected. He was easily the successor of Dorsey, Jones and Minton in the catering business.

11. When the caterer Henry Jones died his funeral procession was actually turned back from the cemetery by the refusal of the authorities of Mt. Moriah Cemetery to allow him interment there; he had before his death bought and paid for a lot in the cemetery and the Supreme Court eventually confirmed his title. To-day this absurd prejudice is not so strong and Negroes own lots in the Episcopal Cemetery of St. James the Less and in perhaps one other.

12. The following clipping from the Philadelphia Ledger, November 2, 1896, illustrates a typical life:

“Robert Adger, a colored Abolitionist, died on Saturday, at his home, 835 South street. He was born a slave, in Charleston, S. C., in 1813. His mother, who was born in New York, went to South Carolina about 1810, with some of her relatives, and while there was detained as a slave.

“When his master died, Mr. Adger, together with his mother and other members of the family, were sold at auction, but, through the assistance of friends, legal proceedings were instituted, and their release finally secured. Mr. Adger then came to this city about 1845, and secured a position as a waiter in the old Merchants’ Hotel. Later he was employed as a nurse, and while working in that capacity, saved enough money to start in the furniture business on South street, above Eighth, which he continued to conduct with success until his death. Mr. Adger always took an active interest in the welfare of the people of his race.”

13. One enterprising capitalist hires and sub-rents eight different houses with furnished apartments, paying $1,944 annually in rent; he has a bicycle shop which brings in $1,000 a year for an expense of about $330. He also owns a barber shop which brings in about $1,000 a year; one-half the gross receipts of this he pays to a foreman, who pays his journeymen barbers; the owner pays for rent and material. “If I had an education,” he said, “I could get on better.”

14. Several storekeepers have had white persons enter the store, look at the proprietors and say “Oh! I—er—made a mistake,” and go out.

15. Here was a case where some persons sought to drive an enterprising and talented Negro out of business simply because he was colored. A Chestnut street property owner made a special effort to give him a start and now he conducts a business of which no merchant need be ashamed.

16. The large steel manufactory known as the “Midvale Steel Works” is located at Nicetown, near Germantown, in Philadelphia County. This establishment was visited by the writer, and the manager of the establishment interviewed as to the success of the experiment made by him in employing Negroes as workmen along with whites.

About 1,200 men are employed altogether, and fully 200 of these are Negroes. About 40 per cent of the whole number of employes are American-born, but generally of Irish, English or German parentage. The remaining 43 per cent are foreign-born, chiefly English, Irish and German, with a few Swedes.

“Our object in putting Negroes on the force,” said the manager, “was twofold. First, we believed them to be good workmen; secondly, we thought they could be used to get over one difficulty we had experienced at Midvale, namely, the clannish spirit of the workmen and a tendency to form cliques. In steel manufacture much of the work is done with large tools run by gangs of men; the work was crippled by the different foremen trying always to have the men in their gang all of their own nationality. The English foreman of a hammer gang, for instance, would want only Englishmen, and the Irish Catholics only Irishmen. This was not good for the works, nor did it promote friendliness among the workmen. So we began bringing in Negroes and placing them on different gangs, and at the same time we distributed the other nationalities. Now our gangs have, say, one Negro, one or two Americans, an Englishman, etc. The result has been favorable both for the men and for the works. Things run smoothly, and the output is noticeably greater.”

“The manager was especially questioned about the grade of work done by Negroes and their efficiency as skilled workmen. He said: “They do all the grades of work done by the white workmen. Some of this work is of such a nature that it had been supposed that only very intelligent English and American workmen could be trusted with it. We have 100 colored men doing that skilled work now, and they do it as well as any of the others.”

As to wages, the manager said no discrimination was made between Negroes and whites. They start as laborers at $1.20 a day and “we try to treat them as individuals, not as a herd; they know that good work gives them a chance for better work and better pay. Thus their ambition is aroused; yesterday, for instance, four Negroes saved a furnace worth $30,000. The furnace was full of molten steel, which had become clogged, so that it could not be gotten out in the usual way. A number of powerful men were required to open the side of the furnace. Four colored men volunteered and saved the steel.”

With regard to the relations between white and black workmen the manager said: “We have had no trouble at all. The unions generally hold potential strikes over their employers’ heads to keep the Negro out of employment. There has, however, been no strike in this establishment for seventeen years, and Negroes have been employed for the last seven years.”

Finally the manager declared that according to his belief the Negro workman does not have half a chance to show his ability. “He does good work and betters his condition when he has any inducement to do so.”

ISABEL EATON

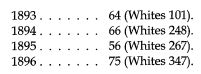

1. The earlier figures are from Dr. Emerson’s reports, in the “Condition,” etc., of the Negro, 1838, and from the pamphlet, “Health of Convicts.” All the tables, 1884 to 1890, are from Dr. John Billings’ report in the Eleventh Census. Later reports are compiled from the City Health Reports, 1890 to 1896.

2. This figure is conjectural, as the real Negro population is unknown. Estimated according to the rate of increase from 1880 to 1890, the average annual population would have been 42,229; I think this is too high, as the rate of increase has been lower in this decade.

3. This and other comparisons are mostly taken from Mayo-Smith, “Statistics and Sociology.”

4. For death rate, 1884–1890, Cf. below, p. 159.

5. The official figures of the Board of Health give no estimate of the Negro death-rate alone. They give the following death rate for the city including both whites and blacks, and excluding stillbirths:

| YEAR | TOTAL NUMBER OF DEATHS | DEATH RATE PER 1000 OF POPULATION |

| 1891 | 23,367 | 21.85 |

| 1892 | 24,305 | 22.25 |

| 1893 | 23,655 | 21.20 |

| 1894 | 22,680 | 19.90 |

| 1895 | 23,796 | 20.44 |

| 1896 | 23,982 | 20.17 |

Average death rate for the six years, 20.97; by my calculation, the rate for the whole population would be 21.63.

6. Cf. Atwater & Woods: “Dietary Studies with reference to the Food of the Negro in Alabama.” (Bulletin No. 38, U. S. Dept. of Agriculture), p. 21, and passim.

7. Dr. Dudley Pemberton before the State Homeopathic Medical Society.—Philadelphia Ledger, October 1, 1896.

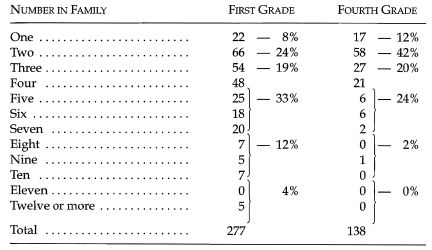

1. Families who were lodging—and there were many—were counted as families, not as lodgers. They were mostly young couples with one or no children. The lodgers were not counted with the families because of their large numbers, and the shifting of many of them from month to month.

2. This figure is obtained by dividing the total population of the ward by the number of homes directly rented, viz., 1675. There is an error here arising from the fact that some sub-renting families are really lodgers and should be counted with the census family, while others are partially separate families and some wholly separate. This error cannot be eliminated.

3. The excessive infant mortality also has its influence on the average size of families. Cf. Chapter X. Whether infanticide or fœticide is prevalent to any extent there are no means of knowing. Once in a while such a case finds its way to the courts.

4. During the last ten years I have been bidden to a dozen or more weddings among the better class of Negroes. In no case was the bridegroom under 30, or the bride under 20. In most cases the man was about 35, and the woman 25 or more.

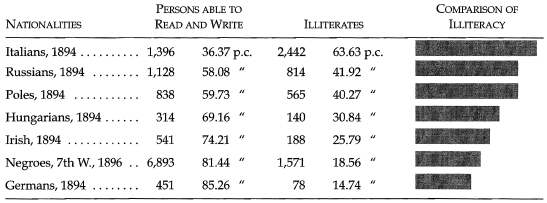

5. The figures relative to other groups of city Negroes as collected by the conference at Atlanta University are as follows:

These figures apply to only 1,137 families in the above named and other cities. Cf. “U. S. Bulletin of Labor,” May, 1897.

6. The birth rate for the city is given in official returns as follows:

1894. Total for city: males, 16,185; females, 14,552. Negroes: males, 536; females, 476.

1895. Total for city: males, 15,618; females, 14,220. Negroes: males, 568; females, 524.

1896. Total for city: males, 15,534; females, 14,219. Negroes: males, 572; females 514.

Average per year for whites, 29,013.

Average per year for Negroes, 1,063.

White birth rate, 27.2 per thousand.

Negro birth rate, 25.1 per thousand.

Assuming white population as 1,066,985.

Assuming Negro population as 41,500.

The Department of Health declares these returns considerably below the truth, and the omissions among Negroes are of course large. Nevertheless, the Negro birth rate in Philadelphia is probably not high.

7. There were many families who were undoubtedly tempted to exaggerate their income so as to appear better off than they were; others, on the contrary, understated their resources. In most cases, however, the testimony so far as it went appeared to be candid and honest.

8. Cf. Booth’s “Life and Labor of the People,” II, 21. In this case I have combined Booth’s two lower classes, “lowest” and “very poor.” I shall discuss the criminal and lowest class in Chapters XIII and XIV. The separation of the “poor” and “very poor” in the Seventh Ward is somewhat arbitrary. I have called all those receiving $150 and less a year “very poor.”

9. Only a few reliable budgets are subjoined, and they are typical. A large number might have been gathered, but they would hardly have added much to these.

10. These estimates are by lifelong residents of Philadelphia, who have had unusual opportunity of knowing the men of whom they speak. One says, “I have prepared an estimate which I herein enclose. I have endeavored to be as conservative as possible. There are, doubtless, several omitted because they are not known, or if known are not now thought of; but I believe the estimate is approximately correct.”

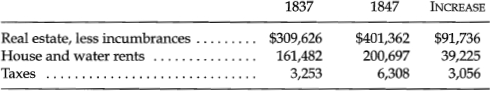

11. The figures for 1821 are from assessors’ reports, quoted in the investigation of 1838. The figures for 1832 are from a memorial to the Legislature, in which the Negroes say that by reference to the receipts of taxpayers which were “actually produced,” they paid at least $2,500 in taxes, and had also $100,000 in church property. From this the inquiry of 1,838 estimates that they owned $357,000 outside church property. The same study estimates the property of Negroes in 1838 as follows:

| REAL ESTATE (TRUE VALUE) | PERSONAL PROPERTY | |

| City | $241,962 | $505,322 |

| Northern Liberties | 26,700 | 35,539 |

| Kensington | 2,255 | 3,825 |

| Spring Garden | 5,935 | 21,570 |

| Southwark | 15,355 | 26,848 |

| Moyamensing | 30,325 | 74,755 |

| $322,532 | $667,859 | |

| Encumbrances | 12,906 | |

| $309,626 |

The report says: “This amount must, of course, be received as only an approximation of the truth.” Fifteen church edifices, a cemetery and hall are not included in the above. “Condition,” etc., 1838. pp. 7, 8.

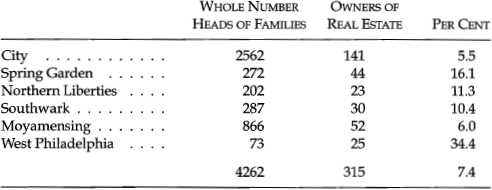

The investigation in 1847–18, gave the following results:

| VALUE REAL ESTATE | ENCUMBRANCES | |

| City | $368,842 | $78,421 |

| Spring Garden | 27,150 | 11,050 |

| Northern Liberties | 40,675 | 13,440 |

| Southwark | 31,544 | 5,915 |

| Moyamensing | 51,973 | 20,216 |

| West Philadelphia | 11,625 | 1,400 |

| $531,809 | $130,442 |

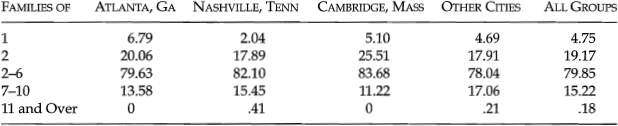

This property was distributed as follows:

| The occupations of the 315 freeholders was as follows: |

| 78 laborers |

| 49 traders |

| 41 mechanics |

| 35 coachmen and hackmen |

| 28 waiters |

| 20 barbers |

| 11 professional men |

| 53 females |

| 315 |

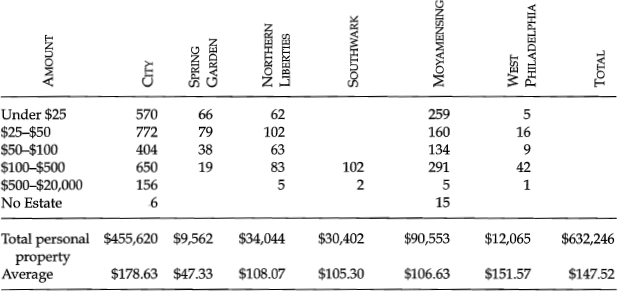

The personal property was as follows.

”Statistical Inquiuy,” etc. p.15.

A comparison between 1838 and 1848 was made by Needles’ “Progress,” etc., pp. 8, 9.

The Inquiry of 1856, pp.15, 16, declares that the previous year the Negroes owned:

| Real and personal property (true value) | $2,685,693.00 |

| Taxes paid | 9,766.42 |

| House, water and ground rent | 396,782.27 |

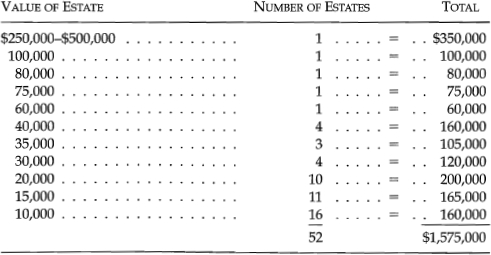

A detailed estimate for 1897 gives the following:

The total of $1,575,000 is the estimated wealth of the well-to-do.

This estimate is as reliable as can be obtained, and is probably nor far from the real facts.

12. There is more property than this owned, but only the answers that seemed reliable and definite were recorded. Most of this property is in the country districts of the South.

13. Many efforts were made to get official data on the matter of property, but the authorities had no way of even approximately distinguishing the races.

14. For an account of a partial investigation of this subject and some attempts at reform, see “Report of Citizens’ Permanent Relief Committee, etc., 1893–4,” pp. 31, ff. Cf. Also the work of the Star Kitchen at Seventh and Lombard streets, Philadelphia.

15. Once in a while the affairs of one of these companies are revealed to the public, as for instance, the following noted in the Public Ledger, October 20, 1896. The company became bankrupt, and its affairs were found hopelessly involved.

“This was the scheme, according to the former agent and some of the certificate holders. Upon the payment of ten cents a week for seven years, the subscriber was promised $100, to be paid at the end of the seventh year. In a year ten cents a week would amount to $5.20; in seven years to $36.40. The Keystone Investment Company promised to give $100 for $36.40.

“Later the assessment was raised to fifteen cents a week. This would amount in seven years to $54.60, for which sum $100 was promised in return. Some few of the certificate holders paid twenty cents a week, it is said. This, in seven years, would amount to $72.80, for which sum, according to the agreement, the certificate holder was to be paid $100.

“Just how many subscribers the company had it is impossible to learn from the officers. A gentleman, who has a store next door to the company’s office, said yesterday that a great many people went there each week to pay their assessments. They appeared to be poor people, he said. There were a great many Negroes among them, and some of them, he said, came from New Jersey.

“The concern started in business in 1891, and has always occupied its present quarters, which are very unpretentious, by the way, for a financial company of any standing. A lady residing on Girard avenue, east of Hanover street, yesterday related her experience with the company as follows:

“ ‘I invested in certificates for my mother and my little daughter, paying fifteen cents a week on each. The agreement was that each was to receive $100 at the end of seven years. I have been paying for my little girl nearly three years, and for my mother nearly two years. It will be two years next Christmas. The payments were made regularly. On both certificates I have paid in about $35.’ ”

16. As before noted, I am aware that a few of these societies do not wholly deserve this sweeping condemnation, and that all of them are defended by certain short-sighted persons as encouraging savings. My observation convinces me, however, of the substantial truth of my conclusions. Of course, all this has nothing to do with the legitimate life insurance business.

1. Cf. Chapter III.

2. St. Thomas’, Bethel and Zoar. The history of Zoar is of interest. It “extends over a period of one hundred years, being as it is an offspring of St. George’s Church, Fourth and Vine streets, the first Methodist Episcopal church to be established in this country, and in whose edifice the first American Conference of that denomination was held. Zoar Church had its origin in 1794, when members of St. George’s Church established a mission in what was then known as Campingtown, now known as Fourth and Brown streets, at which place its first chapel was built. There it remained until 1883, when economic and sociological causes made necessary the selection of a new site. The city had grown, and industries of a character in which the Negroes were not interested had developed in the neighborhood, and, as the colored people were rapidly moving to a different section of the city, it was decided that the church should follow, and the old building was sold. Through the liberality of Colonel Joseph M. Bennett a brick building was erected on Melon street, above Twelfth.

“Since then the congregation has steadily increased in numbers, until in August of this year it was found necessary to enlarge the edifice. The corner-stone of the new front was laid two months ago. The present membership of the church is about 550.”—Public Ledger, November 15, 1897.

3. See Douglass’ “Annals of St. Thomas’.”

4. It was then turned into a private school and supported largely by an English educational fund.

5. St. Thomas’ has suffered often among Negroes from the opprobrium of being “aristocratic,” and is to-day by no means a popular church among the masses. Perhaps there is some justice in this charge, but the church has nevertheless always been foremost in good work and has many public spirited Negroes on its rolls.

6. Cf. U. S. Census, Statistics of Churches, 1890.

7. In 1809 the leading Negro churches formed a “Society for Suppressing Vice and Immorality,’’ which received the endorsement of Chief Justice Tilghman, Benjamin Franklin, Jacob Rush, and others.

8. “Condition of Negroes, 1838,” pp. 39–40.

9. Cf. Robert Jones’ “Fifty years in Central Church.” John Gloucester began preaching in 1807 at Seventh and Bainbridge.

10. In 1847 there were 19 churches; 12 of these had 3974 members; 11 of the edifices cost $67,000. “Statistical Inquiry,” 1848, pp. 29, 30.

In 1854 there were 19 churches reported and 1677 Sunday-school scholars. Bacon, 1856.

11. See Inquiry of 1867.

12. Cf. Publications of Atlanta University No. 3, “Efforts of American Negroes for Social Betterment”.

13. An account of the present state of the A. M. E. Church from its own lips is interesting, in spite of its somewhat turgid rhetoric. The following is taken from the minutes of Philadelphia Conference, 1897:

REPORT ON STATE OF THE CHURCH

“To the Bishop and Conference: We your Committee on State of the Church beg leave to submit the following:

“Every truly devoted African Methodist is intensely interested in the condition of the church that was handed down to us as a precious heirloom from the hands of a God-fearing, self-sacrificing ancestry; the church that Allen planted in Philadelphia, a little over a century ago has enjoyed a marvelous development. Its grand march through the procession of a hundred years has been characterized by a series of brilliant successes, completely refuting the foul calumnies cast against it and overcoming every obstacle that endeavored to impede its onward march, giving the strongest evidence that God was in the midst of her; she should not be moved.

“From the humble beginnings in the little blacksmith shop, at Sixth and Lombard streets, Philadelphia, the Connection has grown until we have now fifty-five annual conferences, beside mission fields, with over four thousand churches, the same number of itinerant preachers, near six hundred thousand communicants, one and a half million adherents, with six regularly organized and well-manned departments, each doing a magnificent work along special lines, the whole under the immediate supervision of eleven bishops, each with a marked individuality and all laboring together for the further development and perpetuity of the church. In this the Mother Conference of the Connection, we have every reason to be grateful to Almighty God for the signal blessings. He has so graciously poured out upon us. The spiritual benedictions have been many. In response to earnest effort and faithful prayers by both pastors and congregations, nearly two thousand persons have professed faith in Christ, during this conference year. Five thousand dollars have been given by the membership and friends of the Connectional interests to carry on the machinery of the church, besides liberal contributions for the cause of missions, education, the Sunday-school Union and Church Extension Departments, and beside all this, the presiding elder and pastors have been made to feel that the people are perfectly willing to do what they can to maintain the preaching of the word, that tends to elevate mankind and glorify God.

“The local interests have not been neglected; new churches have been built, parsonages erected, church mortgages have been reduced, auxiliary societies to give everybody in the church a chance to work for God and humanity, have been more extensively organized than ever before.

“The danger signal that we see here and there cropping out, which is calculated to bring discredit upon the Church of Christ, is the unholy ambition for place and power. The means oft-times used to bring about the desired results, cause the blush of shame to tinge the brow of Christian manhood. God always has and always will select those He designs to use as the leaders of his Church.

“Political methods that are in too many instances resorted to, are contrary to the teaching and spirit of the Gospel of Christ. Fitness and sobriety will always be found in the lead.

“Through mistaken sympathy we find that several incompetent men have found their way into the ministerial ranks; men who can neither manage the financial nor spiritual interests of any church or bring success along any line, who are continuously on the wing from one conference to the other. The time has come when the strictest scrutiny must be exercised as to purpose and fitness of candidates, and if admitted and found to be continuous failures, Christian charity demands that they be given an opportunity to seek a calling where they can make more success than in the ministry. These danger signals that flash up now and then must be observed and everything contrary to the teachings of God’s word and the spirit of the discipline weeded out. The church owes a debt of gratitude to the fathers who have always remained loyal and true; who labored persistently and well for the upbuilding of the connection, that they can never repay.

“Particular care should be taken that no honorable aged minister of our great Church should be allowed to suffer for the necessaries of life. We especially commend to the consideration of every minister the Ministers’ Aid Association, which is now almost ready to be organized, the object of which is to help assuage the grief and dry the tears of those who have been left widowed and fatherless.

“Our Publication Department is making heroic efforts for the larger circulation of our denominational papers and literature generally. These efforts ought to be, and must needs be heartily seconded by the Church. Lord Bacon says: ‘Talking makes a ready man, writing an exact man, but reading makes a full man.’ We want our people at large to be brimful of information relative to the growth of the church, the progress of the race, the upbuilding of humanity and the glory of God.

“Our missionary work must not be allowed to retrograde. The banner that Allen raised must not be allowed to trail, but must go forward until the swarthy sons of Ham everywhere shall gaze with a longing and loving look upon the escutcheon that has emblazoned on it, as its motto: ‘The Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of man,’ and the glorious truth flashing over the whole world that Jesus Christ died to redeem the universal family of mankind. Disasters and misfortunes may come to us, but strong men never quail before adversities. The clouds of to-day may be succeeded by the sunshine of to-morrow.”

14. Cf., e.g., the account of the founding of new missions in the minutes of the Philadelphia Conference, 1896.

15. Baptists themselves recognize this. One of the speakers in a recent association meeting, as reported by the press, “deprecated the spirit shown by some churches in spreading their differences to their detriment as church members, and in the eyes of their white brethren; and he recommended that unworthy brethren from other States, who sought an asylum of rest here, be not admitted to local pulpits except in cases where the ministers so applying are personally known or vouched for by a resident pastor. The custom of recognizing as preachers men incapable of doing good work in the pulpit, who were ordained in the South after they had failed in the North, was also condemned, and the President declared that the times demand a ministry that is able to preach. The practice of licensing incapable brethren for the ministry, simply to please them, was also looked upon with disfavor, and it was recommended that applicants for ordination be required to show at least ability to read intelligently the Word of God or a hymn.”

16. One movement deserves notice—the Woman’s Auxiliary Society. It consists of five circles, representing a like number of colored Baptist churches in this city, viz., the Cherry Street, Holy Trinity, Union, Nicetown and Germantown, and does general missionary work.

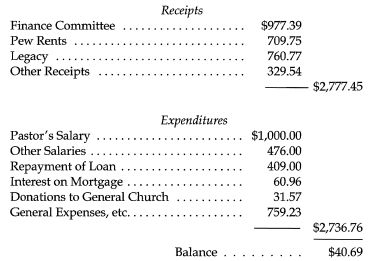

17. See, Jones’ “Fifty Years in Central Street Church,” etc. The system and order in this church is remarkable. Each year a careful printed report of receipts and expenditures is made. The following is an abstract of the report for 1891:

18. For history and detailed account of this work see Anderson’s “Presbyterianism and the Negro.”

19. Rev. Charles Daniel, in the Nazarene. The writer hardly does justice to the weird witchery of those hymns sung thus rudely.

20. Cf. report of inquiries in above years.

21. From Report of Fourth Annual Meeting of the District Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, G. U. of O. F., 1896.

22. This association has issued a valuable little pamphlet called “Helpful Hints on Home,” which it distributes. This explains the object and methods of building and loan associations.

24. The College Settlement was interested in this organization, but the movement was evidently premature.

25. See supra, p. 117 and p. 119.

26. An interesting advertisement of this venture is appended; it is a curious mixture of business, exhortation and simplicity. The present state of the enterprise is not known:

“NOTICE TO ALL.

“WE CALL YOUR ATTENTION

“TO THIS WORK.

“THE UNION TIN-WARE MANUFACTURING CO.

“Is now at work, chartered under the laws of the States of New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

“The purpose of said Company is to manufacture everything in the TIN-WARE LINE that the law allows, and to sell stock all over the United States of America; and put in members enough in every city to open a Union Tin-Ware Store, and if the promoter finds that he has not enough members in a city to open a Tin-Ware Store, then he shall open it with money from the factory. SHARES are $10.00, they can be paid on installment plan; and you do not have any monthly dues to pay, but on the 20th of every December or whenever the Stockholders appoint the time, the dividend will be declared.

“We will make this one of the grandest organizations ever witnessed by the Race, if you lend us your aid. This Store will contain Groceries, Dry Goods and Tin-Ware, and you can do your dealing at your own store. This factory will give you work, and learn you a trade.”

27. Since the opening of the hospital colored nurses have had less trouble in white institutions, and one colored physician has been appointed intern in a large hospital. Dr. N. F. Mossell was chiefly instrumental in founding the Douglass Hospital.

28. In connection with this work, Bethel Church often holds small receptions for servant girls on their days off, when refreshments are served and a pleasant time is spent. The following is a note of a similar enterprise at another church: “The members of the Berean Union have opened a ‘Y’ parlor, where young colored girls employed as domestics can spend their Thursday afternoon both pleasantly and profitably. The parlor is open from 4 until 10 p. m., every Thursday, and members of the Union are present to welcome them. A light supper is served for ten cents. The evening is spent in literary exercises and social talk. The parlor is in the Berean Church, South College avenue, near Twentieth street.”

1. Throughout this chapter the basis of induction is the number of prisoners received at different institutions and not the prison population at particular times. This avoids the mistakes and distortions of the latter method. (Cf. Falkner: “Crime and the Census,” Publications of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, No. 190). Many writers on Crime among Negroes, as e.g., F. L. Hoffman, and all who use the Eleventh Census uncritically, have fallen into numerous mistakes and exaggerations by carelessness on this point.

2. “Pennsylvania Colonial Records,” I, 380–81.

3. See Chapter III, and Appendix B.

4. Cf. “Pennsylvania Statutes at Large,” Ch. 56.

5. Watson’s “Annals,” I, 62.

6. Ibid.

8. “Pennsylvania Colonial Records,” II, 275; IX, 6; “Watson’s Annals,” I, 309.

9. Cf. Chapter IV.

10. Reports Eastern Penitentiary.

11. Average length of sentences for whites in Eastern Penitentiary during nineteen years, 2 years 8 months 2 days; for Negroes, 3 years 3 months 14 days. Cf. “Health of Convicts” (pam.), pp. 7, 8.

12. Ibid., “Condition of Negroes,” 1838, pp. 15–18; “Condition,” etc., 1848, pp. 26, 27.

13. “Condition of Negroes,” 1849, pp. 28, 29. “Condition,” etc., 1838, pp. 15–18.

14. “The large proportion of colored men who, in April, had been before the criminal court, led Judge Gordon to make a suggestion when he yesterday discharged the jurors for the term. ‘It would certainly seem,’ said the Court, ‘that the philanthropic colored people of the community, of whom there are a great many excellent and intelligent citizens sincerely interested in the welfare of their race, ought to see what is radically wrong that produces this state of affairs and correct it, if possible. There is nothing in history that indicates that the colored race has a propensity to acts of violent crime; on the contrary, their tendencies are most gentle, and they submit with grace to subordination.’ ” Philadelphia Record, April 29, 1893; Cf. Record, May 10 and 12; Ledger, May 10, and Times, May 22, 1893.

15. Except as otherwise noted, the statistics of this section are from the official reports of the police department.

16. Cf. Chapters IV and VII.

17. The chief element of uncertainty lies in the varying policy of the courts, as for instance, in the proportion of prisoners sent to different places of detention, the severity of sentence, etc. Only the general conclusions are insisted on here.

18. For the collection of the material here compiled, I am indebted to Mr. David N. Fell, Jr., a student of the Senior Class, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania, in the year ‘96–’97. As before noted the figures in this Section refer to the number of prisoners received at the Eastern Penitentiary, and not to the total prison population at any particular time.

19. Witness the case of Marion Stuyvesant accused of the murder of the librarian Wilson, in 1897.

20. The following Negroes were measured by the Bertillon system in Philadelphia during the last three years:

The arrests by detectives for five years are given below.

CRIMES OF NEGROES ARRESTED BY DETECTIVES, 1887–1892

21. Although the police lieutenants have reported to the Superintendent that few policy shops exist, the Ledger has information which leads it to state that such is not the fact. Many complaints against the evil have been received at this office. A reporter found it easy to locate and gain admittance to a number of houses where policy is written. A policy writer who is thoroughly informed as to the inside working of the system is authority for the statement that at no time in recent years has policy playing been so prevalent or the business carried on as openly as it is now.

While the locations of the policy shops are well known and the writers familiar to many persons, the backers, who, after all, are the substantial part of the system, are hard to reach, for they exercise an unusual cunning in the direction of the business. There are several backers in Philadelphia of greater or less pretensions, but a young man who resides uptown and operates principally in the territory north of Girard avenue, is said to be the heaviest backer of the game in this city. He owns sixty or seventy “books,” and his income from their combined receipts is sufficient to support himself and several relatives in magnificent style.

A Ledger reporter spent one day last week looking up the policy shops in one of the sections where this backer operates. He found, in addition to several places where policy is written, the rendezvous of the writers and the headquarters of the policy king himself.

The writers who hold “books” from the backer in question meet twice every day, Sundays excepted, in a mean, dirty little house overlooking the Reading tracks, just below Montgomery avenue. They enter by the rear through a narrow alley leading off Delhi street, several yards below Montgomery avenue. At noon and at 6 o’clock in the evening the writers hurry to this rendezvous.

The unusual number of men gathering at this point at regular intervals, and the business-like manner in which they go through the alley and back gate is enough to attract the attention of the Twelfth District policeman on this beat and arouse his suspicions. Whether he notices it or not, these proceedings have been going on for months.

Each writer, when he reaches this central point, turns in his “book” and receipts. There are two drawings daily, hence the two meetings. Two relatives of the backer receive the “books” and the money. A copy of each writer’s “book” and all the money are carried by one of these men to the house of an ex-special policeman, a few squares away, and there turned over to the backer, who has received a telegram from Cincinnati stating the numbers that have come out at that drawing.

The “books” are carefully gone over, to see if there are any “hits.” If there are they are computed, and the backer sends to each writer the amount necessary to pay his losses. The numbers that appear at each drawing are printed with rubber stamps in red ink, on slips of white paper and given to the writers to distribute among the players.

These drawings are usually carried to the rendezvous by the ex-policeman. The backer pockets the half day’s receipts, mounts his bicycle and rides away.

To establish beyond a doubt the character of the building in which the writers meet, the reporter made his way into it on the afternoon in question. It is a well-known policy shop, conducted by a colored man, who has been writing policy for years. He is president of a colored political club, with headquarters near by. On the occasion of the visit the back gate was ajar. Pushing it open, the reporter walked in without challenge—From the Public Ledger, December 3, 1897.

1. See Appendix B for these various laws.

2. “Condition,” etc., 1838.

3. “Condition,” etc., 1848.

4. Cf. The “Civic Club Digest” for general information.

5. From reports of police department. Many other official reports might be added to these, but they are easily accessible.

6. From the Society records, by courtesy of the officers.

7. From the C. O. S. records, Seventh District, by courtesy of Miss Burke.

8. This coincidence in figures was entirely unnoticed until both had been worked out by independent methods.

9. I am indebted to Dr. S. M. Lindsay and the students of the Wharton School for the carrying out of this plan.

10. No comparison of the number of Negroes and whites for the ward can be made, because many of the saloons omitted are frequented by whites principally.

1. “Condition,” etc., 1848, p. 16.

2. Not taking into account sub-rent repaid by sub-tenants; subtracting this and the sum would be, perhaps, $1,000,000—see infra, p. 291. That paid by single lodgers ought not, of course, to be subtracted as it has not been added in.

3. The returns as to rents paid are among the most reliable of the statistics gathered. The amount of rent is always well known, and there are few motives for deception. Moreover in Philadelphia there is a tendency to build rows and streets of houses with the same general design. These rent for the same sum, and thus particular instances of false report are easily detected. One feature of the returns must be noted, i.e., the large number of cases where high rents are paid for one- and two-room tenements. In nearly all of these cases this rent is paid for large front bedrooms in good localities, and often includes furniture. Sometimes a limited use of the family kitchen is also included. In such cases it is misleading to call these one-room tenements. No other arrangement, however, seemed practical in these tables.

4. Here, again, the proportion paid by single lodgers must not be subtracted as it has not been added in before.

5. The sentiment has greatly lessened in intensity during the last two decades, but it is still strong; cf. section 47.

6. At the same time, from long custom and from competition, their wages for this work are not high.

7. One room under such circumstances may not by any means denote excessive poverty or indecency; the room is usually rented in a good locality and is well furnished. Cf. note 3.

8. During the plague of that year a census of the inhabitants remaining in the city was taken. Fivesixths of the Negroes remained, so the census gives a good idea of the distribution of the Negro population. The results are published in the report printed afterward by order of Councils.

9. The figures for 1838 and 1848 are from the inquiries of those dates; cf. census of 1840.

10. “Condition of Negroes,” 1848, pp. 34–41.

11. “Mysteries and Miseries of Philadelphia.” (Pamphlet.)

12. Dr. Frances Van Gasken in a tract published by the Civic Club.

13. Ibid.

14. It will be noted that this classification differs materially from the economic division in Chapter XI. In that case grade four and a part of three appear as the “poor;” grade two and the rest of grade three, as the “fair to comfortable;” and a few of grade two and grade one as the well-to-do. The basis of division there was almost entirely according to income; this division brings in moral considerations and questions of expenditure, and consequently reflects more largely the personal judgment of the investigator.

15. The investigator resided at the College Settlement, Seventh and Lombard streets, some months, and thus had an opportunity to observe this slum carefully.

16. These figures were taken during the inquiry by the visitor to the houses.