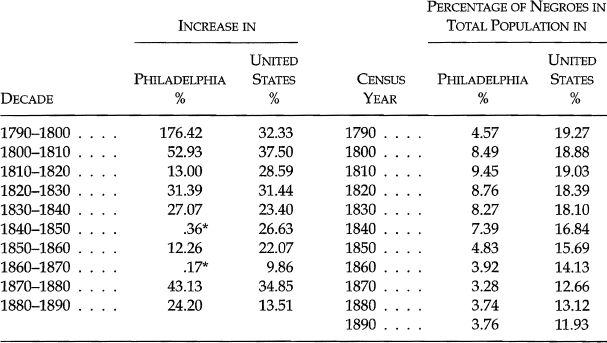

13. The City for a Century—The population of the county1 of Philadelphia increased about twenty-fold from 1790 to 1890; starting with 50,000 whites and 2500 Negroes at the first census, it had at the time of the eleventh census, a million whites and 40,000 Negroes. Comparing the rate of increase of these two elements of the population we have:

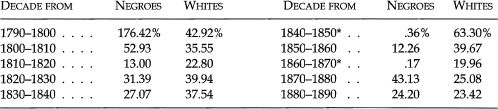

RATES OF INCREASE OF NEGROES AND WHITES

*Decrease for Negroes.

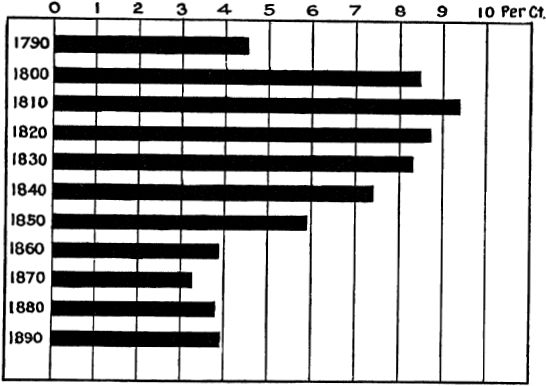

The first two decades were years of rapid increase for the Negroes, their number rising from 2489 in 1790 to 10,552 in 1810. This was due to the incoming of the new freedmen and of servants with masters, all to some extent attracted by the social and industrial opportunities of the city. The white population during this period also increased largely, though not so rapidly as the Negroes, rising from 51,902 in 1790 to 100, 688 in 1810. During the next decade the war had its influence on both races although it naturally had its greatest effect on the lower which increased only 13 per cent against an increase of 28.6 per cent among the Negroes of the country at large. This brought the Negro population of the county to 11,891, while the white population stood at 123,746. During the next two decades, 1820 to 1840, the Negro population rose to 19,833, by natural increase and immigration, while the white population, feeling the first effects of foreign immigration, increased to 238,204. For the next thirty years the continued foreign arrivals, added to natural growth, caused the white population to increase nearly three-fold, while the same cause combined with others allowed an increase of little more than 2000 persons among the Negroes, bringing the black population up to 22,147. In the last two decades the rush to cities on the part of both white and black has increased the former to 1,006,590 souls and the latter to 39,371. The following table gives the exact figures for each decade:

POPULATION OF PHILADELPHIA, 1790–1890

*These totals include Chinese, Indians, etc.

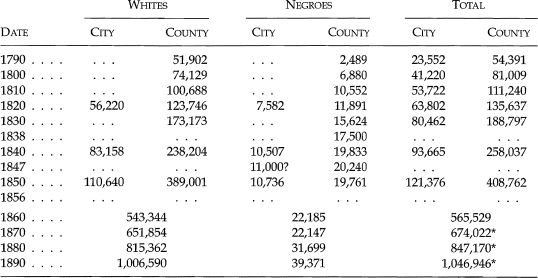

INCREASE OF THE NEGRO POPULATION IN PHILADELPHIA FOR A CENTURY.

[NOTE.—Each horizontal line represents an increment of 2500 persons in population; the upright lines represent the decades. The broken diagonal shows the course of Negro population, and the arrows above recall historic events previously referred to as influencing the increase of the Negroes. At the base of the upright lines is a figure giving the percentage which the Negro population formed of the total population.]

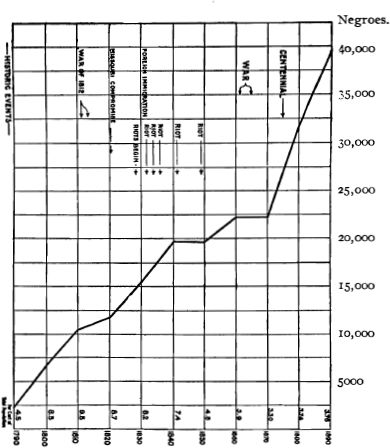

The Negro has never formed a very large percent of the population of the city, as this diagram shows:

PROPORTION OF NEGROES IN TOTAL POPULATION OF PHILADELPHIA.

A glance at these tables shows how much more sensitive the lower classes of a population are to great social changes than the rest of the group; prosperity brings abnormal increase, adversity, abnormal decrease in mere numbers, not to speak of other less easily measurable changes. Doubtless if we could divide the white population into social strata, we would find some classes whose characteristics corresponded in many respects to those of the Negro. Or to view the matter from the opposite standpoint we have here an opportunity of tracing the history and condition of a social class which peculiar circumstances have kept segregated and apart from the mass.

If we glance beyond Philadelphia and compare conditions as to increase of Negro population with the situation in the country at large we can make two interesting comparisons: the rate of increase in a large city compared with that in the country at large; and the changes in the proportion of Negro inhabitants in the city and the United States.

INCREASE OF NEGROES IN THE UNITED STATES AND IN THE CITY OF PHILADELPHIA COMPARED

*Decrease.

A glance at the proportion of Negroes in Philadelphia and in the United States shows how largely the Negro problems are still problems of the country. (See diagram of the proportion of Negroes in the total population of Philadelphia and of the United States on next page.)

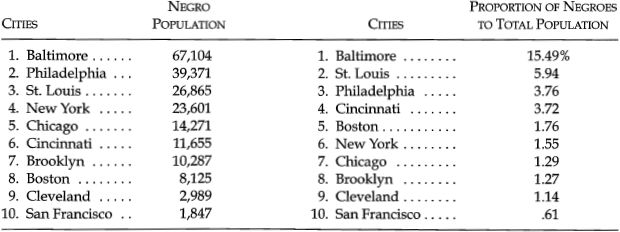

This is even more striking if we remember that Philadelphia ranks high in the absolute and relative number of its Negro inhabitants. For the ten largest cities in the United States we have:

TEN LARGEST CITIES IN THE UNITED STATES ARRANGED ACCORDING TO NEGRO POPULATION

Of all the large cities in the United States, only three have a larger absolute Negro population than Philadelphia: Washington, New Orleans and Baltimore. We seldom realize that none of the great Southern cities, except the three mentioned, have a colored population approaching that of Philadelphia:

COLORED* POPULATION OF LARGE SOUTHERN CITIES

* Includes Chinese, Japanese and civilized Indians, an insignificant number in these cases.

Taken by itself, the Negro population of Philadelphia is no insignificant group of men, as the foregoing diagrams show. (See page 33.)

In other words, we are studying a group of people the size of the capital of Pennsylvania in 1890, and as large as Philadelphia itself in 1800.

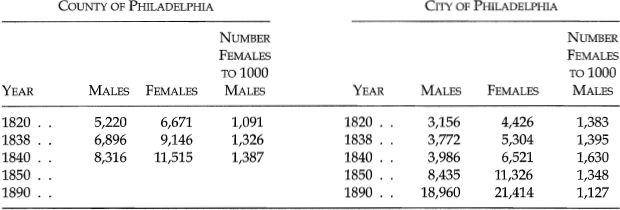

Scanning this population more carefully, the first thing that strikes one is the unusual excess of females. This fact, which is true of all Negro urban populations, has not often been noticed, and has not been given its true weight as a social phenomenon.2 If we take the ten cities having the greatest Negro populations, we have this table:3

COLORED* POPULATION OF TEN CITIES BY SEX

| CITES | MALES | FEMALES |

| Washington | 33,831 | 41,866 |

| New Orleans | 28,936 | 35,727 |

| Baltimore | 29,165 | 38,131 |

| Philadelphia | 18,960 | 21,414 |

| Richmond, Va. | 14,216 | 18,138 |

| Nashville | 13,334 | 16,061 |

| Memphis | 13,333 | 15,396 |

| Charleston, S. C. | 14,187 | 16,849 |

| St. Louis | 13,247 | 13,819 |

| Louisville, Ky. | 13,348 | 15,324 |

| Total | 192,557 | 232,725 |

| Proportion | 1,000 | 1208.5 |

*Includes Chinese, Japanese and civilized Indians—an element that can be ignored, being small.

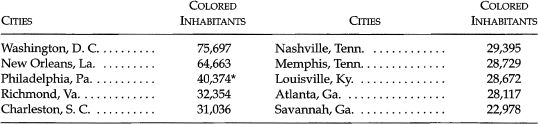

This is a very marked excess and has far-reaching effects. In Philadelphia this excess can be traced back some years

PHILADELPHIA NEGROES BY SEX4

The cause of this excess is easy to explain. From the beginning the industrial opportunities of Negro women in cities have been far greater than those of men, through their large employment in domestic service. At the same time the restriction of employments open to Negroes, which perhaps reached a climax in 1830–1840, and which still plays a great part, has served to limit the number of men. The proportion, therefore, of men to women is a rough index of the industrial opportunities of the Negro. At first there was a large amount of work for all, and the Negro servants and laborers and artisans poured into the city. This lasted up until about 1820, and at that time we find the number of the sexes approaching equality in the county, although naturally more unequal in the city proper. In the next two decades the opportunities for work were greatly restricted for the men, while at the same time, through the growth of the city, the demand for female servants increased, so that in 1840 we have about seven women to every five men in the county, and sixteen to every five in the city. Industrial opportunities for men then gradually increased largely through the growth of the city, the development of new callings for Negroes and the increased demand for male servants in public and private. Nevertheless the disproportion still indicates an unhealthy condition, and its effects are seen in a large percent of illegitimate births, and an unhealthy tone in much of the social intercourse among the middle class of the Negro population.5

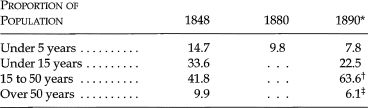

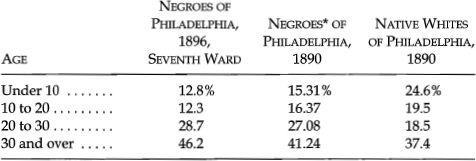

Looking now at the age structure of the Negroes, we notice the disproportionate number of young persons, that is, women between eighteen and thirty and men between twenty and thirty-five. The colored population of Philadelphia contains an abnormal number of young untrained persons at the most impressionable age; at the age when, as statistics of the world show, the most crime is committed, when sexual excess is more frequent, and when there has not been developed fully the feeling of responsibility and personal worth. This excess is more striking in recent years than formerly, although full statistics are not available:

*Including Chinese, Japanese and Indians.

†15 to 55.

‡Over 55.

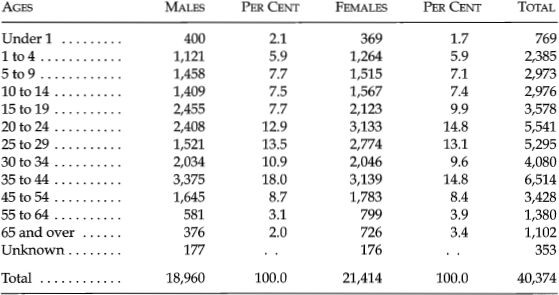

This table is too meager to be conclusive, but it is probable that while the age structure of the Negro urban population in 1848 was about normal, it has greatly changed in recent years. Detailed statistics for 1890 make this plainer:

NEGROES* OF PHILADELPHIA BY SEX AND AGE, 1890

*Includes 1003 Chinese, Japanese and Indians.

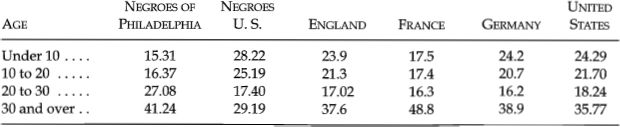

Comparing this with the age structure of other groups we have this table:6

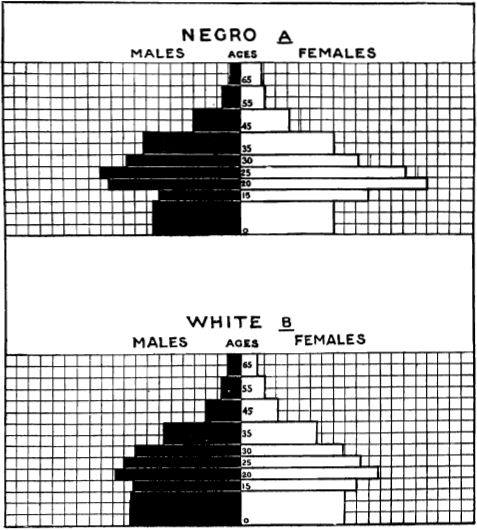

In few large cities does the age structure approach the abnormal condition here presented; the most obvious comparison would be with the age structure of the whites of Philadelphia, for 1890, which may be thus represented:

We find then in Philadelphia a steadily and, in recent years, rapidly growing Negro population, in itself as large as a good-sized city, and characterized by an excessive number of females and of young persons.

14. The Seventh Ward, 1896—We shall now make a more intensive study of the Negro population, confining ourselves to one typical ward for the year 1896. Of the nearly forty thousand Negroes in Philadelphia in 1890, a little less than a fourth lived in the Seventh Ward, and over half in this and the adjoining Fourth, Fifth and Eighth Wards:

| WARD | NEGROES | WHITES |

| Seventh | 8,861 | 21,177 |

| Eighth | 3,011 | 13,940 |

| Fourth | 2,573 | 17,792 |

| Fifth | 2,335 | 14,619 |

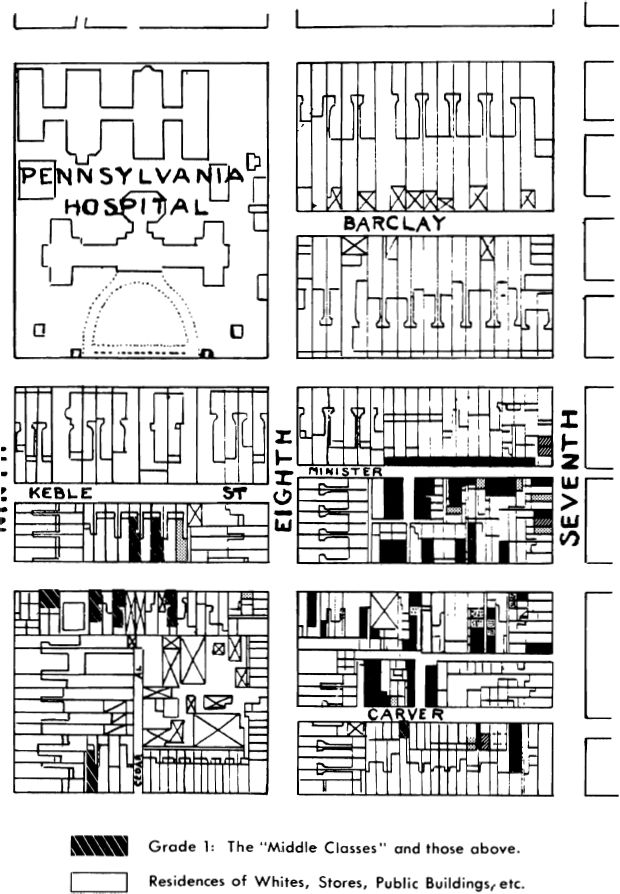

The distribution of Negroes in the other wards may be seen by the accompanying map. (See opposite page.)

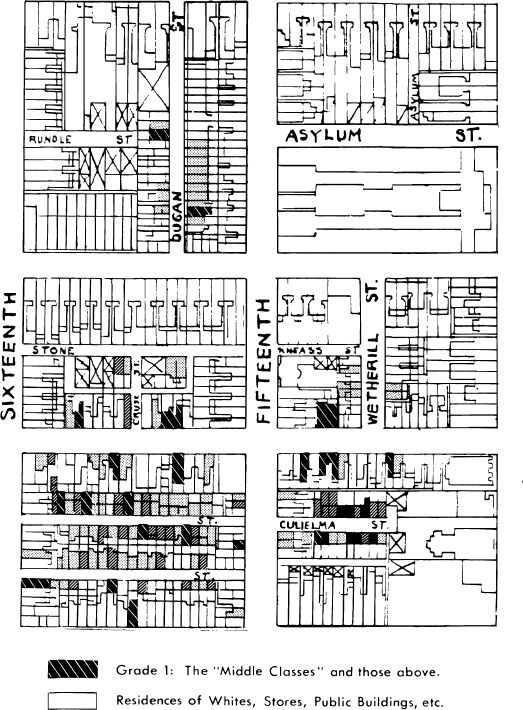

The Seventh Ward starts from the historic centre of Negro settlement in the city, South Seventh street and Lombard, and includes the long narrow strip, beginning at South Seventh and extending west, with South and Spruce streets as boundaries, as far as the Schuylkill River. The colored population of this ward numbered 3621 in 1860, 4616 in 1870, and 8861 in 1890. It is a thickly populated district of varying character; north of it is the residence and business section of the city; south of it a middle class and workingmen’s residence section; at the east end it joins Negro, Italian and Jewish slums; at the west end, the wharves of the river and an industrial section separating it from the grounds of the University of Pennsylvania and the residence section of West Philadelphia.

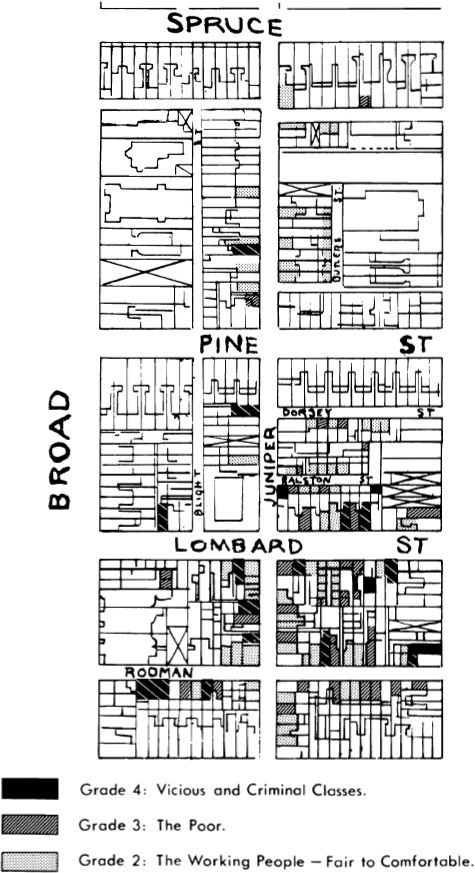

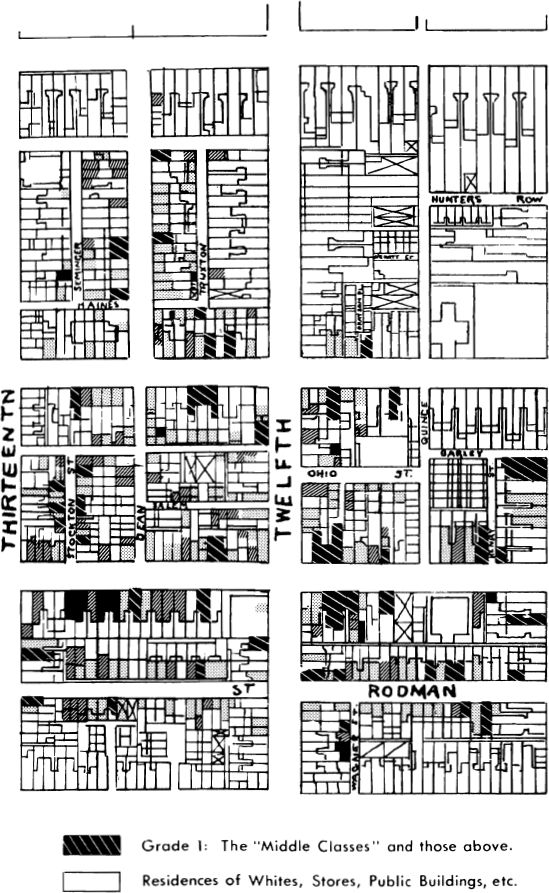

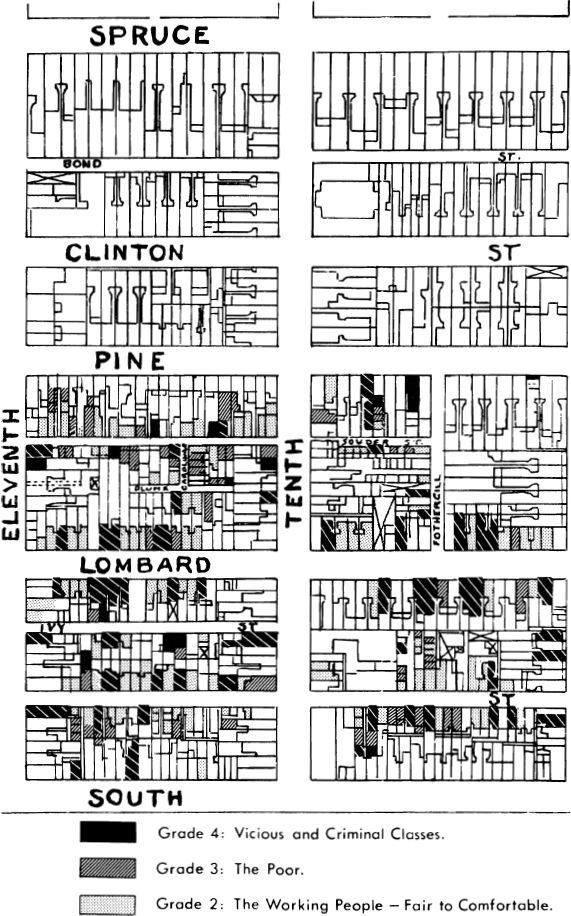

Starting at Seventh street and walking along Lombard, let us glance at the general character of the ward. Pausing a moment at the corner of Seventh and Lombard, we can at a glance view the worst Negro slums of the city. The houses are mostly brick, some wood, not very old, and in general uncared for rather than dilapidated. The blocks between Eighth, Pine, Sixth and South have for many decades been the centre of Negro population. Here the riots of the thirties took place, and here once was a depth of poverty and degradation almost unbelievable. Even to-day there are many evidences of degradation, although the signs of idleness, shiftlessness, dissoluteness and crime are more conspicuous than those of poverty. The alleys7 near, as Ratcliffe street, Middle alley, Brown’s court, Barclay street, etc., are haunts of noted criminals, male and female, of gamblers and prostitutes, and at the same time of many poverty-stricken people, decent but not energetic. There is an abundance of political clubs, and nearly all the houses are practically lodging houses, with a miscellaneous and shifting population. The corners, night and day, are filled with Negro loafers—able-bodied young men and women, all cheerful, some with good-natured, open faces, some with traces of crime and excess, a few pinched with poverty. They are mostly gamblers, thieves and prostitutes, and few have fixed and steady occupation of any kind. Some are stevedores, porters, laborers and laundresses. On its face this slum is noisy and dissipated, but not brutal, although now and then highway robberies and murderous assaults in other parts of the city are traced to its denizens. Nevertheless the stranger can usually walk about here day and night with little fear of being molested, if he be not too inquisitive.8

Passing up Lombard, beyond Eighth, the atmosphere suddenly changes, because these next two blocks have few alleys and the residences are good-sized and pleasant. Here some of the best Negro families of the ward live. Some are wealthy in a small way, nearly all are Philadelphia born, and they represent an early wave of emigration from the old slum section.9 To the south, on Rodman street, are families of the same character. North of Pine and below Eleventh there are practically no Negro residences. Beyond Tenth street, and as far as Broad street, the Negro population is large and varied in character. On small streets like Barclay and its extension below Tenth—Souder, on Ivy, Rodman, Salem, Heins, Iseminger, Ralston, etc., is a curious mingling of respectable working people and some of a better class, with recent immigrations of the semi-criminal class from the slums. On the larger streets, like Lombard and Juniper, there live many respectable colored families—native Philadelphians, Virginians and other Southerners, with a fringe of more questionable families. Beyond Broad, as far as Sixteenth, the good character of the Negro population is maintained except in one or two back streets.10 From Sixteenth to Eighteenth, intermingled with some estimable families, is a dangerous criminal class. They are not the low, open idlers of Seventh and Lombard, but rather the graduates of that school: shrewd and sleek politicians, gamblers and confidence men, with a class of well-dressed and partially undetected prostitutes. This class is not easily differentiated and located, but it seems to centre at Seventeenth and Lombard. Several large gambling houses are near here, although more recently one has moved below Broad, indicating a reshifting of the criminal centre. The whole community was an earlier immigration from Seventh and Lombard. North of Lombard, above Seventeenth, including Lombard street itself, above Eighteenth, is one of the best Negro residence sections of the city, centring about Addison street. Some undesirable elements have crept in even here, especially since the Christian League attempted to clear out the Fifth Ward slums,11 but still it remains a centre of quiet, respectable families, who own their own homes and live well. The Negro population practically stops at Twenty-second street, although a few Negroes live beyond.

We can thus see that the Seventh Ward presents an epitome of nearly all the Negro problems; that every class is represented, and varying conditions of life. Nevertheless one must naturally be careful not to draw too broad conclusions from a single ward in one city. There is no proof that the proportion between the good and the bad here is normal, even for the race in Philadelphia; that the social problems affecting Negroes in large Northern cities are presented here in most of their aspects seems credible, but that certain of those aspects are distorted and exaggerated by local peculiarities is also not to be doubted.

In the fall of 1896 a house-to-house visitation was made to all the Negro families of this ward. The visitor went in person to each residence and called for the head of the family. The housewife usually responded, the husband now and then, and sometimes an older daughter or other member of the family. The fact that the University was making an investigation of this character was known and discussed in the ward, but its exact scope and character was not known. The mere announcement of the purpose secured, in all but about twelve cases,12 immediate admission. Seated then in the parlor, kitchen, or living room, the visitor began the questioning, using his discretion as to the order in which they were put, and omitting or adding questions as the circumstances suggested. Now and then the purpose of a particular query was explained, and usually the object of the whole inquiry indicated. General discussions often arose as to the condition of the Negroes, which were instructive. From ten minutes to an hour was spent in each home, the average time being fifteen to twenty-five minutes.

Usually the answers were prompt and candid, and gave no suspicion of previous preparation. In some cases there was evident falsification or evasion. In some cases there was evident falsification or evasion. In such cases the visitor made free use of his best judgment and either inserted no answer at all, or one which seemed approximately true. In some cases the families visited were not at home, and a second or third visit was paid. In other cases, and especially in the case of the large class of lodgers, the testimony of landlords and neighbors often had to be taken.

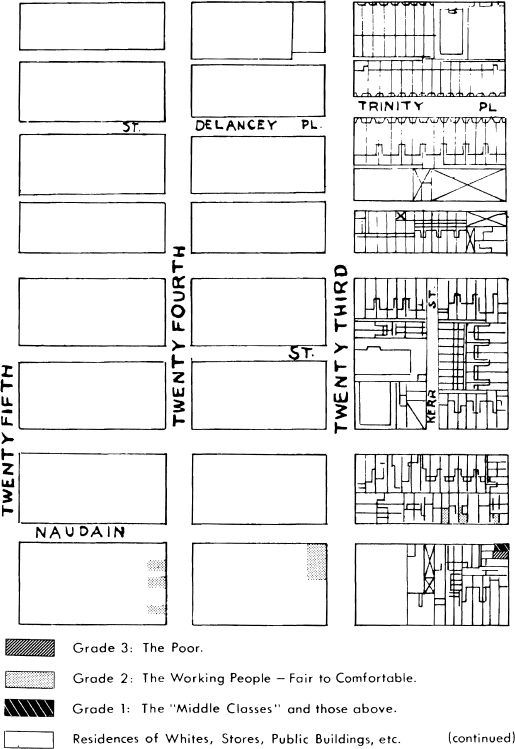

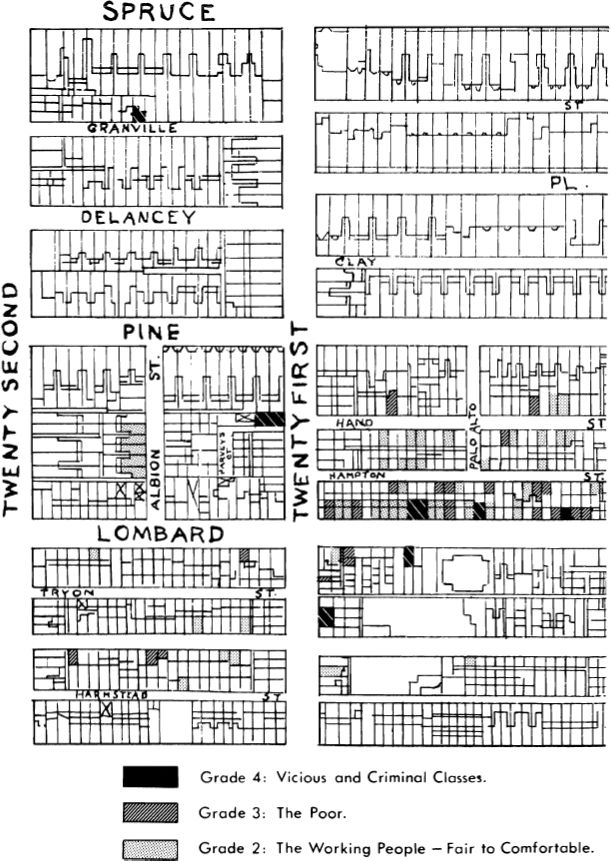

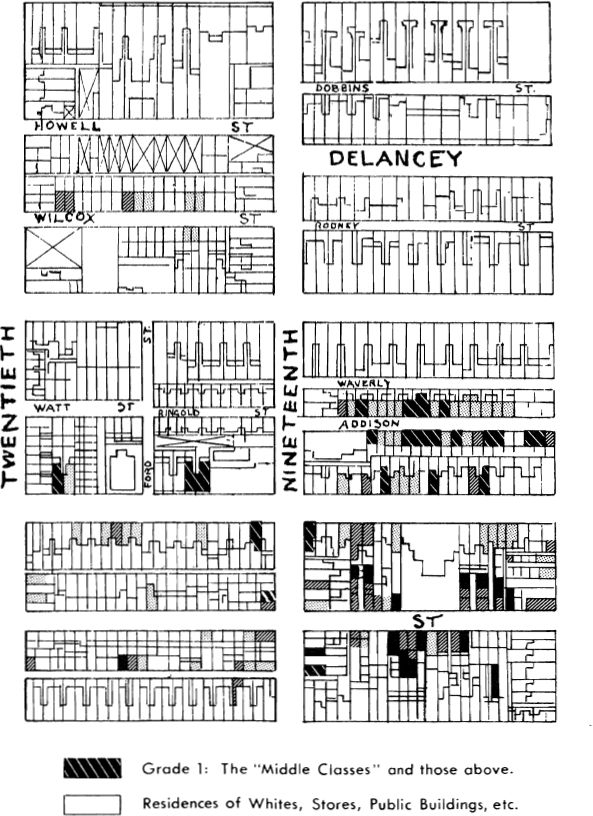

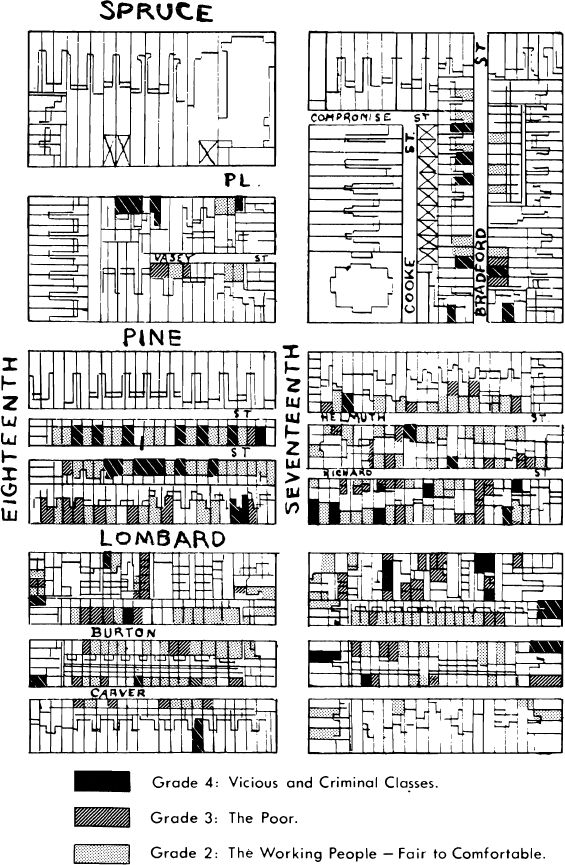

The Seventh Ward of Philadelphia

The Distribution of Negro Inhabitants Throughout the Ward, and their social condition

(For a more detailed explanation of the meaning of the different grades, see § 46, chap. xv)

No one can make an inquiry of this sort and not be painfully conscious of a large margin of error from omissions, errors of judgment and deliberate deception. Of such errors this study has, without doubt, its full share. Only one fact was peculiarly favorable and that is the proverbial good nature and candor of the Negro. With a more cautious and suspicious people much less success could have been obtained. Naturally some questions were answered better than others; the chief difficulty arising in regard to the questions of age and income. The ages given for people forty and over have a large margin of error, owing to ignorance of the real birthday. The question of income was naturally a delicate one, and often had to be gotten at indirectly. The yearly income, as a round sum, was seldom asked for; rather the daily or weekly wages taken and the time employed during the year.

On December 1, 1896, there were in the Seventh Ward of Philadelphia 9675 Negroes; 4501 males and 5174 females. This total includes all persons of Negro descent, and thirty-three intermarried whites.13 It does not include residents of the ward then in prisons or in almshouses. There were a considerable number of omissions among the loafers and criminals without homes, the class of lodgers and the club-house habitués. These were mostly males, and their inclusion would somewhat affect the division by sexes, although probably not to a great extent.14 The increase of the Negro population in this ward for six and a half years is 814, or at the rate of 14.13 per cent per decade. This is perhaps somewhat smaller than that for the population of the city at large, for the Seventh Ward is crowded and overflowing into other wards. Possibly the present Negro population of the city is between 43,000 and 45,000. At all events it is probable that the crest of the tide of immigration is passed, and that the increase for the decade 1890–1900 will not be nearly as large as the 24 per cent of the decade 1880–1890.

NEGRO POPULATION OF SEVENTH WARD

| AGE | MALE | FEMALE | |

| Under 10 | 570 | 641 | |

| 10 to 19 | 483 | 675 | |

| 20 to 29 | 1,276 | 1,444 | |

| 30 to 39 | 1,046 | 1,084 | |

| 40 to 49 | 553 | 632 | |

| 50 to 59 | 298 | 331 | |

| 60 to 69 | 114 | 155 | |

| 70 and over | 41 | 96 | |

| Age unknown | 120 | 116 | |

| Total | 4,501 | 5,174 | |

| Grand total | 9,675 |

The division by sex indicates still a very large and, it would seem, growing excess of women. The return shows 1150 females to every 1000 males. Possibly through the omission of men and the unavoidable duplication of some servants lodging away from their place of service, the disproportion of the sexes is exaggerated. At any rate it is great, and if growing, may be an indication of increased restriction in the employments open to Negro men since 1880 or even since 1890.

The age structure also presents abnormal features.15 Comparing the age structure with that of the large cities of Germany, we have:

| AGE | NEGROES OF PHILADELPHIA | LARGE CITIES OF GERMANY |

| Under 20 | 25.1 | 39.3 |

| 20 to 40 | 51.3 | 37.2 |

| Over 40 | 23.6 | 23.5 |

Comparing it with the Whites and Negroes in the city in 1890, we have:

* Includes 1003 Chinese, Japanese and Indians.

As was noticed in the whole city in 1890, so here is even more striking evidence of the preponderance of young people at an age when sudden introduction to city life is apt to be dangerous, and of an abnormal excess of females.