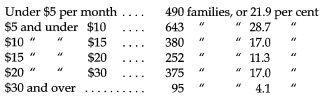

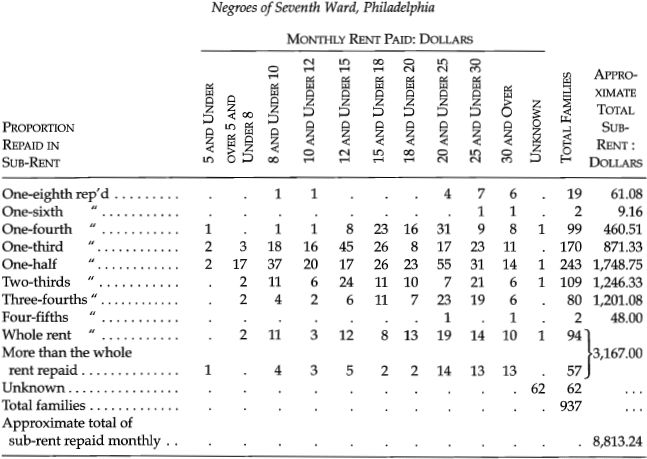

44. Houses and Rent—The inquiry of 1848 returned quite full statistics of rents paid by the Negroes.1 In the whole city at that date 4019 Negro families paid $199,665.46 in rent, or an average of $49.68 per family each year. Ten years earlier the average was $44 per family. Nothing better indicates the growth of the Negro population in numbers and power when we compare with this the figures for 1896 for one ward; in that year the Negroes of the Seventh Ward paid $25,699.50 each month in rent, or $308,034 a year, an average of $126.19 per annum for each family. This ward may have a somewhat higher proportion of renters than most other wards. At the lowest estimate, however, the Negroes of Philadelphia pay at least $1,250,000 in rent each year.2

The table of rents for 1848 is as follows (see page 206):

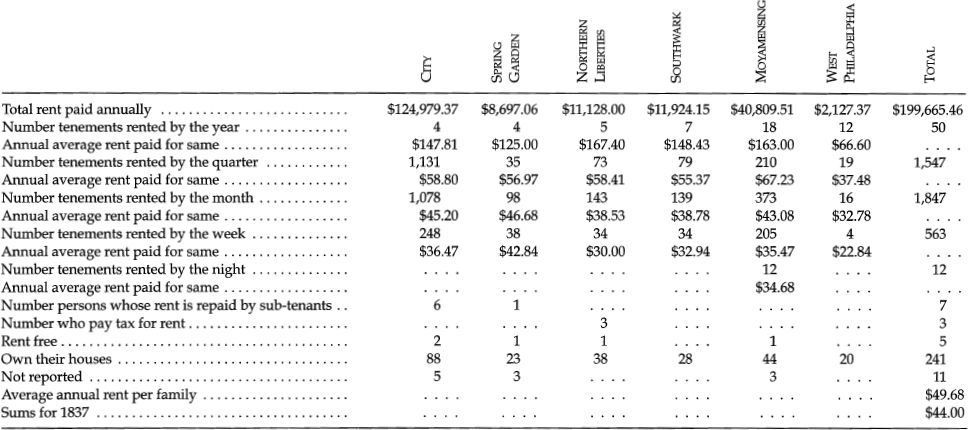

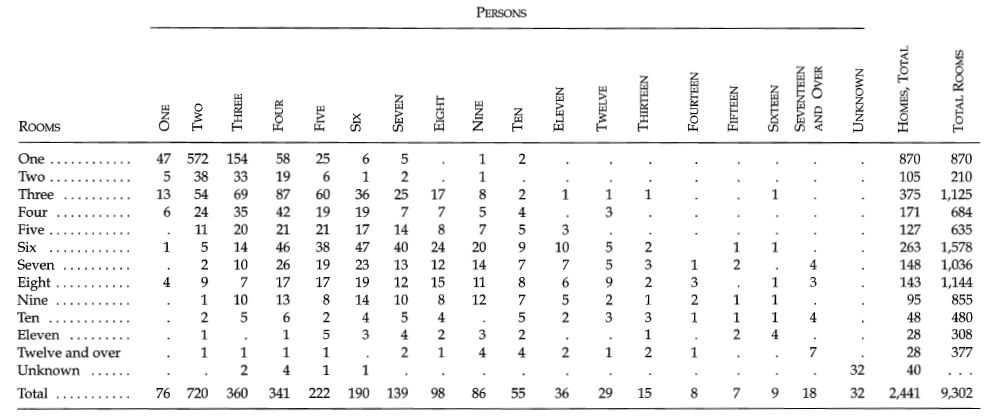

We see that in 1848 the average Negro family rented by the month or quarter, and paid between four and five dollars per month rent. The highest average rent for any section was less than fifteen dollars a month. For such rents the poorest accommodations were afforded, and we know from descriptions that the mass of Negroes had small and unhealthful homes, usually on the back streets and alleys. The rents paid to-day in the Seventh Ward, according to the number of rooms, are tabulated on page 207.

Condensing this table somewhat we find that the Negroes pay rent as follows:

The lodging system so prevalent in the Seventh Ward makes some rents appear higher than the real facts warrant. This ward is in the centre of the city, near the places of employment for the mass of the people and near the centre of their social life; consequently people crowd here in great numbers. Young couples just married engage lodging in one or two rooms; families join together and hire one house; and numbers of families take in single lodgers; thus the population of the ward is made up of

RENTS PAID BY NEGROES OF PHILADELPHIA,1848

NEGRO HOMES, ACCORDING TO RENTS AND ROOMS3

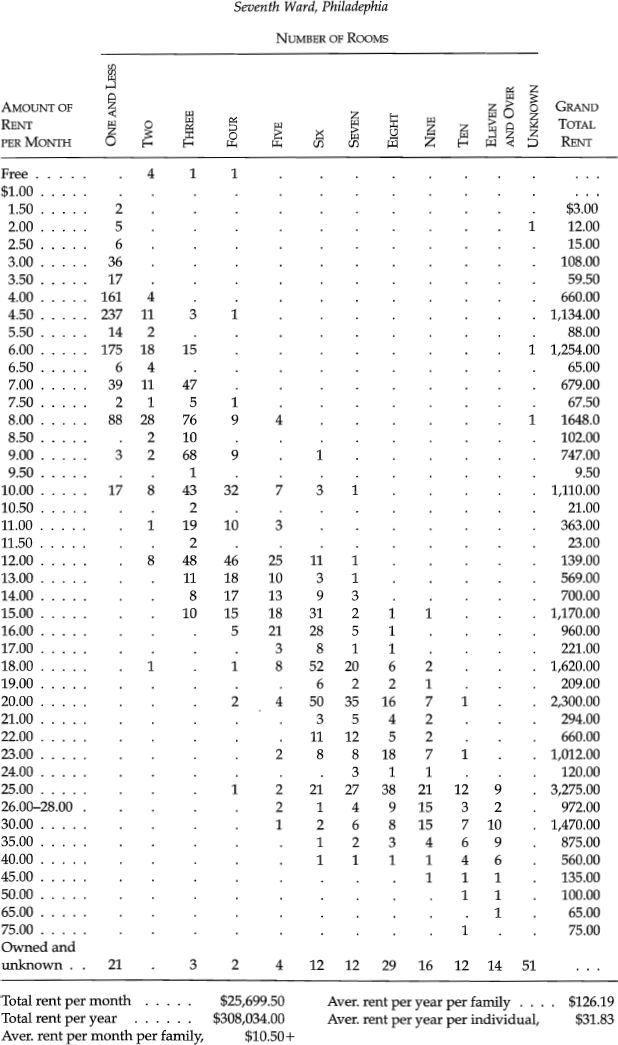

The practice of sub-renting is found of course in all degrees: from the business of boarding-house keeper to the case of a family which rents out its spare bed-chamber. In the first case the rent is practically all repaid, and must in some cases be regarded as income; in the other cases a small fraction of the rent is repaid and the real rent and the size of the home reduced. Let us endeavor to determine what proportion of the rents of the Seventh Ward are repaid in subrents, omitting some boarding and lodging-houses where the sub-rent is really the income of the housewife. In most cases the room-rent of lodgers covers some return for the care of the room. The next table gives detailed statistics:

PROPORTION OF RENT REPAID IN SUB-RENT

It appears from this table that nearly $9,000 is paid by the sub-renting families and lodgers to the renting families. A part of this ought to be subtracted from the total rent paid if we would get at the net rent; just how much, however, should be called wages for care of room, or other conveniences furnished subrenters, it is difficult to say. Possibly the net rent of the ward is $20,000, and of the city about $1,000,000.4

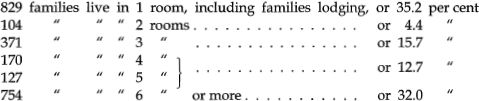

The accommodations furnished for the rent paid must now be considered. The number of rooms occupied is the simplest measurement, but is not very satisfactory in this case owing to the lodging system which makes it difficult to say how many rooms a family really occupies. A very large number of families of two and three rent a single bedroom and these must be regarded as one-room tenants, and yet this renting of a room often includes a limited use of a common kitchen; on the other hand this sub-renting family cannot in justice be counted as belonging to the renting family. The figures are:

The number of families occupying one room is here exaggerated as before shown by the lodging system; on the other hand the number occupying six rooms and more is also somewhat exaggerated by the fact that not all sub-rented rooms have been subtracted, although this has been done as far as possible.

Of the 2,441 families only 334 had access to bathrooms and water-closets, or 13.7 per cent. Even these 334 families have poor accommodations in most instances. Many share the use of one bathroom with one or more other families. The bath-tubs usually are not supplied with hot water and very often have no water-connection at all. This condition is largely owing to the fact that the Seventh Ward belongs to the older part of Philadelphia, built when vaults in the yards were used exclusively and bathrooms could not be given space in the small houses. This was not so unhealthful before the houses were thick and when there were large back yards. To-day, however, the back yards have been filled by tenement houses and the bad sanitary results are shown in the death rate of the ward.

Even the remaining yards are disappearing. Of the 1,751 families making returns, 932 had a private yard 12 × 12 feet, or larger; 312 had a private yard smaller than 12 × 12 feet; 507 had either no yard at all or a yard and outhouse in common with the other denizens of the tenement or alley.

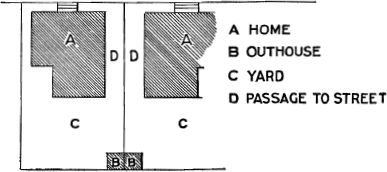

Of the latter only sixteen families had water-closets. So that over 20 per cent and possibly 30 per cent of the Negro families of this ward lack some of the very elementary accommodations necessary to health and decency. And this too in spite of the fact that they are paying comparatively high rents. Here too there comes another consideration, and that is the lack of public urinals and water-closets in this ward and, in fact, throughout Philadelphia. The result is that the closets of tenements are used by the public. A couple of diagrams will illustrate this; the houses of older Philadelphia were built like this:

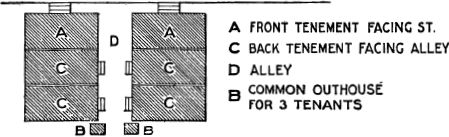

When, however, certain districts like the Seventh Ward became crowded and given over to tenants, the thirst for money-getting led landlords in large numbers of cases to build up their back yards like this:

This is the origin of numbers of the blind alleys and dark holes which make some parts of the Fifth, Seventh and Eighth Wards notorious. The closets in such cases are sometimes divided into compartments for different tenants, but in many cases not even this is done; and in all cases the alley closet becomes a public resort for pedestrians and loafers. The back tenements thus formed rent usually for from $7 to $9 a month, and sometimes for more. They consist of three rooms one above the other, small, poorly lighted and poorly ventilated. The inhabitants of the alley are at the mercy of its worst tenants; here policy shops abound, prostitutes ply their trade, and criminals hide. Most of these houses have to get their water at a hydrant in the alley, and must store their fuel in the house. These tenement abominations of Philadelphia are perhaps better than the vast tenement houses of New York, but they are bad enough, and cry for reform in housing.

The fairly comfortable working class live in houses of 3–6 rooms, with water in the house, but seldom with a bath. A three room house on a small street rents from $10 up; on Lombard street a 5–8 room house can be rented for from $18 to $30 according to location. The great mass of comfortably situated working people live in houses of 6–10 rooms, and sub-rent a part or take lodgers. A 5–7 room house on South Eighteenth street can be had for $20; on Florida street for $18; such houses have usually a parlor, dining room and kitchen on the first floor and two to four bedrooms, of which one or two are apt to be rented to a waiter or coachman for $4 a month, or to a married couple at $6–10 a month. The more elaborate houses are on Lombard street and its cross streets.

The rents paid by the Negroes are without doubt far above their means and often from one-fourth to three-fourths of the total income of a family goes in rent. This leads to much non-payment of rent both intentional and unintentional, to frequent shifting of homes, and above all to stinting the families in many necessities of life in order to live in respectable dwellings. Many a Negro family eats less than it ought for the sake of living in a decent house.

Some of this waste of money in rent is sheer ignorance and carelessness. The Negroes have an inherited distrust of banks and companies, and have long neglected to take part in Building and Loan Associations. Others are simply careless in the spending of their money and lack the shrewdness and business sense of differently trained peoples. Ignorance and carelessness however will not explain all or even the greater part of the problem of rent among Negroes. There are three causes of even greater importance: these are the limited localities where Negroes may rent, the peculiar connection of dwelling and occupation among Negroes and the social organization of the Negro. The undeniable fact that most Philadelphia white people prefer not to live near Negroes5 limits the Negro very seriously in his choice of a home and especially in the choice of a cheap home. Moreover, real estate agents knowing the limited supply usually raise the rent a dollar or two for Negro tenants, if they do not refuse them altogether. Again, the occupations which the Negro follows, and which at present he is compelled to follow, are of a sort that makes it necessary for him to live near the best portions of the city; the mass of Negroes are in the economic world purveyors to the rich—working in private houses, in hotels, large stores, etc.6 In order to keep this work they must live near by; the laundress cannot bring her Spruce street family’s clothes from the Thirtieth Ward, nor can the waiter at the Continental Hotel lodge in Germantown. With the mass of white workmen this same necessity of living near work, does not hinder them from getting cheap dwellings; the factory is surrounded by cheap cottages, the foundry by long rows of houses, and even the white clerk and shop girl can, on account of their hours of labor, afford to live further out in the suburbs than the black porter who opens the store. Thus it is clear that the nature of the Negro’s work compels him to crowd into the centre of the city much more than is the case with the mass of white working people. At the same time this necessity is apt in some cases to be overestimated, and a few hours of sleep or convenience serve to persuade a good many families to endure poverty in the Seventh Ward when they might be comfortable in the Twenty-fourth Ward. Nevertheless much of the Negro problem in this city finds adequate explanation when we reflect that here is a people receiving a little lower wages than usual for less desirable work, and compelled, in order to do that work, to live in a little less pleasant quarters than most people, and pay for them somewhat higher rents.

The final reason of the concentration of Negroes in certain localities is a social one and one peculiarly strong: the life of the Negroes of the city has for years centred in the Seventh Ward; here are the old churches, St. Thomas’, Bethel, Central, Shiloh and Wesley; here are the halls of the secret societies; here are the homesteads of old families. To a race socially ostracised it means far more to move to remote parts of a city, than to those who will in any part of the city easily form congenial acquaintances and new ties. The Negro who ventures away from the mass of his people and their organized life, finds himself alone, shunned and taunted, stared at and made uncomfortable; he can make few new friends, for his neighbors however well-disposed would shrink to add a Negro to their list of acquaintances. Thus he remains far from friends and the concentred social life of the church, and feels in all its bitterness what it means to be a social outcast. Consequently emigration from the ward has gone in groups and centred itself about some church, and individual initiative is thus checked. At the same time color prejudice makes it difficult for groups to find suitable places to move to—one Negro family would be tolerated where six would be objected to; thus we have here a very decisive hindrance to emigration to the suburbs.

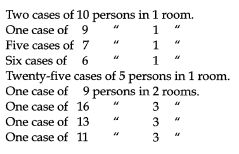

It is not surprising that this situation leads to considerable crowding in the homes, i.e., to the endeavor to get as many people into the space hired as possible. It is this crowding that gives the casual observer many false notions as to the size of Negro families, since he often forgets that every other house has its subrenters and lodgers. It is however difficult to measure this crowding on account of this very lodging system which makes it very often uncertain as to just the number of rooms a given group of people occupy. In the following table therefore it is likely that the number of rooms given is somewhat greater than is really the case and that consequently there is more crowding than is indicated. This error however could not be wholly eliminated under the circumstances; a study of the table (page 213) shows that in the Seventh Ward there are 9,302 rooms occupied by 2,401 families, an average of 3.8 rooms to a family, and 1.04 individuals to a room. A division by rooms will better show where the crowding comes in.

Families occupying five rooms and less: 1,648, total rooms per family, 2.17; total individuals per room, 1.53.

Families occupying three rooms and less: 1,350, total rooms per family, 1.63; total individuals per room, 1.85.

The worst cases of crowding are as follows:

As said before, this is probably something under the real truth, although perhaps not greatly so. The figures show considerable overcrowding, but not nearly as much as is often the case in other cities. This is largely due to the character of Philadelphia houses, which are small and low, and will not admit many inmates. Five persons in one room of an ordinary tenement would be almost suffocating. The large number of one-room tenements with two persons should be noted. These 572 families are for the most part young or childless couples, sub-renting a bedroom and working in the city.7

HOMES ACCORDING TO ROOMS AND PERSONS LIVING IN THEM

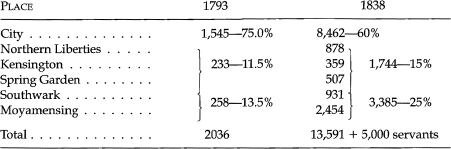

45. Sections and Wards—The spread of Negro population in the city during the nineteenth century is worth studying. In 1793,8 one-fourth of the black inhabitants—or 538 persons—lived north of Market street and south of Vine, and were either in the homes of white families as servants, or in the alleys, as Shively’s, Pewter Platter, Croomb’s, Sugar, Cresson’s, etc. Between Market and South lived one-half of the blacks, crowded in a region that centred at Sixth and Lombard: in Strawberry alley and lane, Elbow lane, Grey’s alley, Shippen’s alley, etc., besides in the families of the whites on Walnut, Spruce, Pine, etc. The remaining fourth of the population was in Southwark, south of South street, and in the Northern Liberties, north of Vine. Details are given in the next table:

NUMBER AND DISTRIBUTION OF THE NEGRO INHABITANTS OF PHILADELPHIA IN 1793—OCTOBER TO DECEMBER

(Taken from the Census of the Plague Committee)

BETWEEN MARKET AND VINE STREETS

| STREETS, ETC. | NEGROES |

| Market | 63 |

| Water | 31 |

| Front | 40 |

| Second | 29 |

| Third | 37 |

| Fourth | 42 |

| Fifth | 24 |

| Sixth | 32 |

| Seventh | 8 |

| Eighth | 13 |

| Ninth | 3 |

| Arch | 56 |

| Race | 38 |

| Vine (south side) | 9 |

| New | 3 |

| Church alley | 2 |

| Quarry | 4 |

| Cherry alley | 25 |

| South alley | 1 |

| North alley | 4 |

| Sugar alley | 14 |

| Appletree alley | 7 |

| Cresson’s alley | 10 |

| Shively’s alley | 11 |

| Pewter Platter alley | 3 |

| Croomb’s alley | 5 |

| Baker’s alley | 7 |

| Brooks’ court | 1 |

| Priest’s alley | 6 |

| Says alley | 6 |

| Total | 538 |

BETWEEN MARKET AND SOUTH STREETS

| STREETS, ETC. | NEGROES |

| Water | 12 |

| Front | 129 |

| Second | 116 |

| Third | 66 |

| Fourth | 81 |

| Fifth | 63 |

| Sixth | 37 |

| Seventh | 0 |

| Eighth | 16 |

| Ninth | 0 |

| Penn | 11 |

| Chestnut | 50 |

| Walnut | 83 |

| Spruce | 66 |

| Pine | 31 |

| South (north side) | 32 |

| Strawberry lane | 4 |

| Strawberry alley | 2 |

| Elbow lane | 10 |

| Beetles’ alley | 5 |

| Grey’s alley | 13 |

| Norris alley | 4 |

| Dock | 5 |

| Union | 32 |

| Cypress alley | 1 |

| Pear | 5 |

| Lombard | 57 |

| Emslie’s alley | 6 |

| Laurel court | 1 |

| Shippen’s alley | 26 |

| Willing’s alley | 1 |

| Blackberry alley | 2 |

| Carpenter | 7 |

| Gaskill | 7 |

| Georges to South | 5 |

| Little Water | 5 |

| Stamper’s alley | 8 |

| Taylor’s alley | 1 |

| York court | 7 |

| Total | 1,007 |

NORTHERN LIBERTIES

| STREETS, ETC. | NEGROES |

| Water | 1 |

| Front | 59 |

| Second | 41 |

| Third | 1 |

| Fourth | 3 |

| Fifth | 1 |

| Vine (north side) | 18 |

| Callowhill | 10 |

| Noble, or Bloody lane | 4 |

| Artillery lane (or Duke) | 26 |

| Green | 6 |

| Coates | 32 |

| Brown | 15 |

| Cable lane | 1 |

| St. John | 6 |

| St. Tammany | 2 |

| Willow | 1 |

| Wood’s alley | 1 |

| Crown | 3 |

| Total | 233 |

DISTRICT OF SOUTHWARK

| STREETS, ETC. | NEGROES |

| Swanson | 22 |

| South Penn | 3 |

| Front | 15 |

| Second | 22 |

| Third | 34 |

| Fifth | 5 |

| Cedar court (south side) | 19 |

| Shippen | 50 |

| Almond | 9 |

| Catharine | 33 |

| Christian | 6 |

| Queen | 5 |

| Meade’s alley | 10 |

| German | 3 |

| Plumb | 5 |

| Moll Tuller’s alley | 4 |

| George | 8 |

| Ball alley | 3 |

| Crabtree alley | 2 |

| Total | 258 |

SUMMARY

| Between Market and Vine streets | 538 |

| Between Market and South streets | 1,007 |

| North of Vine street | 233 |

| South of South street | 258 |

| Total | 2,036 |

| Total inhabitants of county by census of 1790 | 2,489 |

The changes from 1793 to 1838, nearly a half century, may thus be shown:

Thus we see in 1838 that the centre of Negro population had gone southward toward Moyamensing. The Cedar, Locust, Newmarket, Pine and South Wards, as they were then called, had the bulk of the population, and they corresponded approximately to the Fourth, Fifth, Seventh and Eighth Wards of to-day.

Ten years later than this, in 1848,9 we have a more detailed account of the distribution of the Negroes in the various sections of the city. They were mostly crowded into narrow courts and alleys. The colored population north of Vine and east of Sixth streets consisted of 272 families with 1,285 persons. One hundred and one families of these (415 persons) lived on Apple street and its courts, and in Paschall’s alley (now Lynd street). Apple street itself, including Hick’s court, had 37 families, with 138 persons, living in 16 houses; Shotwell’s row, on the same street, had 16 families with 65 persons in 7 houses; the rooms were about 8 feet square. Paschall’s alley contained 48 families with 212 persons, in 28 houses; one house had 7 families, 33 persons, living in 13 rooms, 8 feet square. The rent of the whole house was $266 per year; “yet all of them [i.e., these families] have comfortable beds and bedding.”

About a third of the total Negro population of Moyamensing (the district “south of Cedar street and west of Passyunk road”) was crowded into the space between Fifth and Eighth streets, and South and Fitzwater; for instance:

| FAMILIES | |

| Shippen street | 55 |

| Freytag’s alley | 63 |

| Small street | 73 |

| Baker street | 21 |

| Seventh and South streets | 14 |

| Spafford street | 16 |

| Freytag’s alley | 9 |

| Prosperous alley | 11 |

| Black Horse alley | 5 |

| Hutton’s court | 9 |

| Yeager’s court | 9 |

| Dickerson’s court | 5 |

| Britton’s court | 5 |

| Cryder’s court | 4 |

| Sherman’s court | 13 |

| Total | 302 |

“It is in this district and in the adjoining portion of the city, especially Mary street and its vicinity, that the great destitution and wretchedness exist.” The personal property of 176 of the above 302 families is returned as $603.50, or $3.43 per family; 15 families (42 persons) on Small street (Alaska street) above Sixth, have their whole property valued at $7. Most of these Negroes were ragpickers, and 29 out of 42 families were not natives of the State. Mary street and its courts had 80 families, with 281 persons living in 35 houses. Some were industrious and temperate, but there was “much surrounding misery.” In Gile’s alley (from Cedar to Lombard street) were 42 families, 147 persons, in 20 houses. Eighty-three of these persons were not natives of the State, and 13 of the families received public charity. A description of this district in 1847 is interesting:

“The vicinity of the place we sought was pointed out by a large number of colored people congregated on the neighboring pavements. We first inspected the rooms, yards and cellars of the four or five houses next above Baker street on Seventh. The cellars were wretchedly dark, damp and dirty, and were generally rented for twelve and a half cents per night. These are occupied by one or more families at the present time, but in the winter season when the frost drives those who in summer sleep abroad in fields, in boardyards and in sheds, to seek more effectual shelter, they often contain from twelve to twenty lodgers per night. Commencing at the back of each house are small wooden buildings roughly put together, about six feet square, without windows or fireplaces, a hole about a foot square being left in front along side of the door to let in fresh air and light, and to let out foul air and smoke. These desolate pens, the roofs of which are generally leaky, and their floors so low that more or less water comes in on them from the yard in rainy weather, would not give comfortable winter accommodations to a cow. Although as dismal as dirt, damp and insufficient ventilation can make them, they are nearly all inhabited. In one of the first we entered, we found the dead body of a large Negro man who had died suddenly there. This pen was about eight feet deep by six wide. There was no bedding in it, but a box or two around the sides furnished places where two colored persons, one said to be the wife of the deceased, were lying either drunk or fast asleep. The body of the dead man was on the wet floor beneath an old torn coverlet.”10

In 1853 a similar description of the crime, filth and poverty of this district shows us that the present slums do not compare with those in misfortune and depravity.11 Much of this poverty and degradation could in 1847 be laid at the door of the new immigrants, and although some of the immigrants were in good circumstances, yet in general most of the poverty was found where most of the immigrants were. The immigrants formed the following percentages of the total population in 1847:

| City | 47.7 | per cent |

| Moyamensing | 46.3 | ” |

| Southwark | 35.9 | ” |

| West Philadelphia | 34.3 | ” |

| Spring Garden | 31.4 | ” |

| Northern Liberties | 14.2 | ” |

The historic centre of Negro settlement in the city can thus be seen to be at Sixth and Lombard. From this point it moved north, as is indicated for instance by the establishment of Zoar Church in 1794. Immigration of foreigners and the rise of industries, however, early began to turn it back and it found outlet in the alleys of Southwark and Moyamensing. For a while about 1840 it was bottled up here, but finally it began to move west. A few early left the mass and settled in West Philadelphia; the rest began a slow steady movement along Lombard street. The influx of 1876 and thereafter sent the wave across Broad street to a new centre at Seventeenth and Lombard. There it divided into two streams; one went north and joined remnants of the old settlers in the Northern Liberties and Spring Garden. The other went south to the Twenty-sixth, Thirtieth and Thirty-sixth Wards. Meantime the new immigrants poured in at Seventh and Lombard, while Sixth and Lombard down to the Delaware was deserted to the Jews, and Moyamensing partially to the Italians. The Irish were pushed on beyond Eighteenth to the Schuylkill, or emigrated to the mills of Kensington and elsewhere. The course may be thus graphically represented (see page 219):

This migration explains much that is paradoxical about Negro slums, especially their present remnant at Seventh and Lombard. Many people wonder that the mission and reformatory agencies at work there for so many years have so little to show by way of results. One answer is that this work has new material continually to work upon, while the best classes move to the west and leave the dregs behind. The parents and grandparents of some of the best families of Philadelphia Negroes were born in the neighborhood of Sixth and Lombard at a time when all Negroes, good, bad and indifferent, were confined to that and a few other localities. With the greater freedom of domicile which has since come, these slum districts have sent a stream of emigrants westward. There has, too, been a general movement from the alleys to the streets and from the back to the front streets. Moreover it is untrue that the slums of Seventh and Lombard have not greatly changed in character; compared with 1840, 1850 or even 1870 these slums are much improved in every way. More and more every year the unfortunate and poor are being sifted out from the vicious and criminal and sent to better quarters.

And yet with all the obvious improvement, there are still slums and dangerous slums left. Of the Fifth Ward and adjoining parts of the Seventh, a city health inspector says:

“Few of the houses are underdrained, and if the closets have sewer connections the people are too careless to keep them in order. The streets and alleys are strewn with garbage, excepting immediately after the visit of the street cleaner. Penetrate into one of these houses and beyond into the back yard, if there is one (frequently there is not), and there will be found a pile of ashes, garbage and filth, the accumulation of the winter, perhaps of the whole year. In such heaps of refuse what disease germ may be breeding?”12

To take a typical case:

“Gillis’ Alley, famed in the Police Court, is a narrow alley, extending from Lombard street through to South street, above Fifth street, cobbled and without sewer connections. Houses and stables are mixed promiscuously. Buildings are of frame and of brick. No.—looks both outside and in like a Southern Negro’s cabin. In this miserable place four colored families have their homes. The aggregate rent demanded is $22 a month, though the owner seldom receives the full rent. For three small dark rooms in the rear of another house in this alley, the tenants pay, and have paid for thirteen years, $11 a month. The entrance is by a court not over two feet wide. Except at midday the sun does not shine in the small open space in the rear that answers for a yard. It is safe to say that not one house in this alley could pass an inspection without being condemned as prejudicial to health. But if they are so condemned and cleaned, with such inhabitants how long will they remain clean?”13

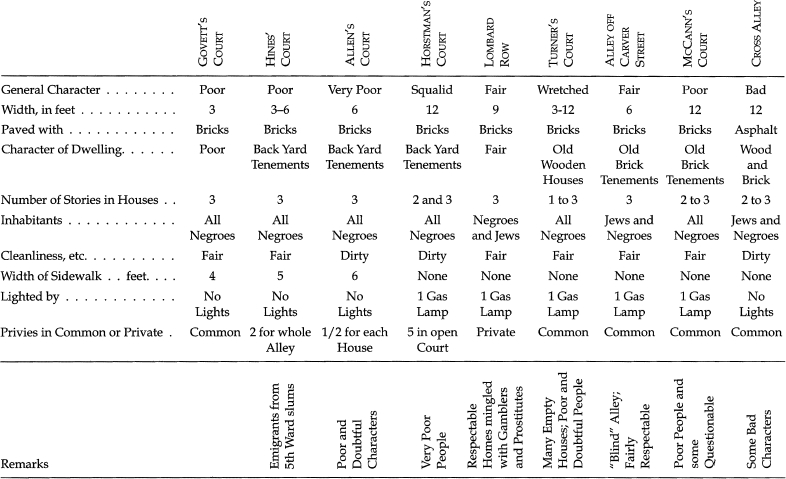

SOME ALLEYS WHERE NEGROES LIVE

Some of the present characteristics of the chief alleys where Negroes live are given in the following table:

The general characteristics and distribution of the Negro population at present in the different wards can only be indicated in general terms. The wards with the best Negro population are parts of the Seventh, Twenty-sixth, Thirtieth and Thirty-sixth, Fourteenth, Fifteenth, Twenty-fourth, Twenty-seventh and Twenty-ninth. The worst Negro population is found in parts of the Seventh, and in the Fourth, Fifth and Eighth. In the other wards either the classes are mixed or there are very few colored people. The tendency of the best migration to-day is toward the Twenty-sixth, Thirtieth and Thirty-sixth Wards, and West Philadelphia.

46. Social Classes and Amusements—Notwithstanding the large influence of the physical environment of home and ward, nevertheless there is a far mightier influence to mold and make the citizen, and that is the social atmosphere which surrounds him: first his daily companionship, the thoughts and whims of his class; then his recreations and amusements; finally the surrounding world of American civilization, which the Negro meets especially in his economic life. Let us take up here the subject of social classes and amusements among Negroes, reserving for the next chapter a study of the contact of the Whites and Blacks.

There is always a strong tendency on the part of the community to consider the Negroes as composing one practically homogeneous mass. This view has of course a certain justification: the people of Negro descent in this land have had a common history, suffer to-day common disabilities, and contribute to one general set of social problems. And yet if the foregoing statistics have emphasized any one fact it is that wide variations in antecedents, wealth, intelligence and general efficiency have already been differentiated within this group. These differences are not, to be sure, so great or so patent as those among the whites of to-day, and yet they undoubtedly equal the difference among the masses of the people in certain sections of the land fifty or one hundred years ago; and there is no surer way of misunderstanding the Negro or being misunderstood by him than by ignoring manifest differences of condition and power in the 40,000 black people of Philadelphia.

And yet well-meaning people continually do this. They regale the thugs and whoremongers and gamblers of Seventh and Lombard streets with congratulations on what the Negroes have done in a quarter century, and pity for their disabilities; and they scold the caterers of Addison street for the pickpockets and paupers of the race. A judge of the city courts, who for years has daily met a throng of lazy and debased Negro criminals, comes from the bench to talk to the Negroes about their criminals: he warns them first of all to leave the slums and either forgets or does not know that the fathers of the audience he is speaking to, left the slums when he was a boy and that the people before him are as distinctly differentiated from the criminals he has met, as honest laborers anywhere differ from thieves.

Nothing more exasperates the better class of Negroes than this tendency to ignore utterly their existence. The law-abiding, hard-working inhabitants of the Thirtieth Ward are aroused to righteous indignation when they see that the word Negro carries most Philadelphians’ minds to the alleys of the Fifth Ward or the police courts. Since so much misunderstanding or rather forgetfulness and carelessness on this point is common, let us endeavor to try and fix with some definiteness the different social classes which are clearly enough defined among Negroes to deserve attention. When the statistics of the families of the Seventh Ward were gathered, each family was put in one of four grades as follows:

Grade 1. Families of undoubted respectability earning sufficient income to live well; not engaged in menial service of any kind; the wife engaged in no occupation save that of house-wife, except in a few cases where she had special employment at home. The children not compelled to be bread-winners, but found in school; the family living in a well-kept home.

Grade 2. The respectable working-class; in comfortable circumstances, with a good home, and having steady remunerative work. The younger children in school.

Grade 3. The poor; persons not earning enough to keep them at all times above want; honest, although not always energetic or thrifty, and with no touch of gross immorality or crime. Including the very poor, and the poor.

Grade 4. The lowest class of criminals, prostitutes and loafers; the “submerged tenth.”

Thus we have in these four grades the criminals, the poor, the laborers, and the well-to-do.14 The last class represents the ordinary middle-class folk of most modern countries, and contains the germs of other social classes which the Negro has not yet clearly differentiated. Let us begin first with the fourth class.

The criminals and gamblers are to be found at such centres as Seventh and Lombard streets, Seventeenth and Lombard, Twelfth and Kater, Eighteenth and Naudain, etc. Many people have failed to notice the significant change which has come over these slums in recent years; the squalor and misery and dumb suffering of 1840 has passed, and in its place have come more baffling and sinister phenomena: shrewd laziness, shameless lewdness, cunning crime. The loafers who line the curbs in these places are no fools, but sharp, wily men who often outwit both the Police Department and the Department of Charities. Their nucleus consists of a class of professional criminals, who do not work, figure in the rogues’ galleries of a half-dozen cities, and migrate here and there. About these are a set of gamblers and sharpers who seldom are caught in serious crime, but who nevertheless live from its proceeds and aid and abet it. The headquarters of all these are usually the political clubs and pool-rooms; they stand ready to entrap the unwary and tempt the weak. Their organization, tacit or recognized, is very effective, and no one can long watch their actions without seeing that they keep in close touch with the authorities in some way. Affairs will be gliding on lazily some summer afternoon at the corner of Seventh and Lombard streets; a few loafers on the corners, a prostitute here and there, and the Jew and Italian plying their trades. Suddenly there is an oath, a sharp altercation, a blow; then a hurried rush of feet, the silent door of a neighboring club closes, and when the policeman arrives only the victim lies bleeding on the sidewalk; or at midnight the drowsy quiet will be suddenly broken by the cries and quarreling of a half-drunken gambling table; then comes the sharp, quick crack of pistol shots—a scurrying in the darkness, and only the wounded man lies awaiting the patrol-wagon. If the matter turns out seriously, the police know where in Minster street and Middle alley to look for the aggressor; often they find him, but sometimes not.15

The size of the more desperate class of criminals and their shrewd abettors is of course comparatively small, but it is large enough to characterize the slum districts. Around this central body lies a large crowd of satellites and feeders: young idlers attracted by excitement, shiftless and lazy ne’er-do-wells, who have sunk from better things, and a rough crowd of pleasure seekers and libertines. These are the fellows who figure in the police courts for larceny and fighting, and drift thus into graver crime or shrewder dissoluteness. They are usually far more ignorant than their leaders, and rapidly die out from disease and excess. Proper measures for rescue and reform might save many of this class. Usually they are not natives of the city, but immigrants who have wandered from the small towns of the South to Richmond and Washington and thence to Philadelphia. Their environment in this city makes it easier for them to live by crime or the results of crime than by work, and being without ambition—or perhaps having lost ambition and grown bitter with the world—they drift with the stream.

One large element of these slums, a class we have barely mentioned, are the prostitutes. It is difficult to get at any satisfactory data concerning such a class, but an attempt has been made. There were in 1896 fifty-three Negro women in the Seventh Ward known on pretty satisfactory evidence to be supported wholly or largely by the proceeds of prostitution; and it is probable that this is not half the real number;16 these fifty-three were of the following ages:

| 14 to 19 | 2 |

| 20 to 24 | 11 |

| 25 to 29 | 9 |

| 30 to 39 | 17 |

| 40 to 49 | 3 |

| 50 and over | 2 |

| Unknown | 9 |

| —— | |

| Total | 53 |

Seven of these women had small children with them and had probably been betrayed, and had then turned to this sort of life. There were fourteen recognized bawdy houses in the ward; ten of them were private dwellings where prostitutes lived and were not especially fitted up, although male visitors frequented them. Four of the houses were regularly fitted up, with elaborate furniture, and in one or two cases had young and beautiful girls on exhibition. All of these latter were seven- or eight-room houses for which $26 to $30 a month was paid. They are pretty well-known resorts, but are not disturbed. In the slums the lowest class of street walkers abound and ply their trade among Negroes, Italians and Americans. One can see men following them into alleys in broad daylight. They usually have male associates whom they support and who join them in “badger” thieving. Most of them are grown women though a few cases of girls under sixteen have been seen on the street.

This fairly characterizes the lowest class of Negroes. According to the inquiry in the Seventh Ward at least 138 families were estimated as belonging to this class out of 2,395 reported, or 5.8 per cent. This would include between five and six hundred individuals. Perhaps this number reaches 1000 if the facts were known, but the evidence at hand furnishes only the number stated. In the whole city the number may reach 3,000, although there is little data for an estimate.17

The next class are the poor and unfortunate and the casual laborers; most of these are of the class of Negroes who in the contact with the life of a great city have failed to find an assured place. They include immigrants who cannot get steady work; good-natured, but unreliable and shiftless persons who cannot keep work or spend their earnings thoughtfully; those who have suffered accident and misfortune; the maimed and defective classes, and the sick; many widows and orphans and deserted wives; all these form a large class and are here considered. It is of course very difficult to separate the lowest of this class from the one below, and probably many are included here who, if the truth were known, ought to be classed lower. In most cases, however, they have been given the benefit of the doubt. The lowest ones of this class usually live in the slums and back streets, and next door or in the same house often, with criminals and lewd women. Ignorant and easily influenced, they readily go with the tide and now rise to industry and decency, now fall to crime. Others of this class get on fairly well in good times, but never get far ahead. They are the ones who earliest feel the weight of hard times and their latest blight. Some correspond to the “worthy poor” of most charitable organizations, and some fall a little below that class. The children of this class are the feeders of the criminal classes. Often in the same family one can find respectable and striving parents weighed down by idle, impudent sons and wayward daughters. This is partly because of poverty, more because of the poor home life. In the Seventh Ward 30½ per cent of the families or 728 may be put into this class, including the very poor, the poor and those who manage just to make ends meet in good times. In the whole city perhaps ten to twelve thousand Negroes fall in this third social grade.

Above these come the representative Negroes; the mass of the servant class, the porters and waiters, and the best of the laborers. They are hard-working people, proverbially good-natured; lacking a little in foresight and forehandedness, and in “push.” They are honest and faithful, of fair and improving morals, and beginning to accumulate property. The great drawback to this class is lack of congenial occupation especially among the young men and women, and the consequent wide-spread dissatisfaction and complaint. As a class these persons are ambitious; the majority can read and write, many have a common school training, and all are anxious to rise in the world. Their wages are low compared with corresponding classes of white workmen, their rents are high, and the field of advancement opened to them is very limited. The best expression of the life of this group is the Negro church, where their social life centres, and where they discuss their situation and prospects.

A note of disappointment and discouragement is often heard at these discussions and their work suffers from a growing lack of interest in it. Most of them are probably best fitted for the work they are doing, but a large percentage deserve better ways to display their talent, and better remuneration. The whole class deserves credit for its bold advance in the midst of discouragements, and for the distinct moral improvement in their family life during the last quarter century. These persons form 56 per cent or 1,252 of the families of the Seventh Ward, and include perhaps 25,000 of the Negroes of the city. They live in 5–10-room houses, and usually have lodgers. The houses are always well furnished with neat parlors and some musical instrument. Sunday dinners and small parties, together with church activities, make up their social intercourse. Their chief trouble is in finding suitable careers for their growing children.

Finally we come to the 277 families, 11.5 per cent of those of the Seventh Ward, and including perhaps 3,000 Negroes in the city, who form the aristocracy of the Negro population in education, wealth and general social efficiency. In many respects it is right and proper to judge a people by its best classes rather than by its worst classes or middle ranks. The highest class of any group represents its possibilities rather than its exceptions, as is so often assumed in regard to the Negro. The colored people are seldom judged by their best classes, and often the very existence of classes among them is ignored. This is partly due in the North to the anomalous position of those who compose this class; they are not the leaders or the ideal-makers of their own group in thought, work, or morals. They teach the masses to a very small extent, mingle with them but little, do not largely hire their labor. Instead then of social classes held together by strong ties of mutual interest we have in the case of the Negroes, classes who have much to keep them apart, and only community of blood and color prejudice to bind them together. If the Negroes were by themselves either a strong aristocratic system or a dictatorship would for the present prevail. With, however, democracy thus prematurely thrust upon them, the first impulse of the best, the wisest and richest is to segregate themselves from the mass. This action, however, causes more of dislike and jealousy on the part of the masses than usual, because those masses look to the whites for ideals and largely for leadership. It is natural therefore that even to-day the mass of Negroes should look upon the worshipers at St. Thomas’ and Central as feeling themselves above them, and should dislike them for it. On the other hand it is just as natural for the well-educated and well-to-do Negroes to feel themselves far above the criminals and prostitutes of Seventh and Lombard streets, and even above the servant girls and porters of the middle class of workers. So far they are justified; but they make their mistake in failing to recognize that, however laudable an ambition to rise may be, the first duty of an upper class is to serve the lowest classes. The aristocracies of all peoples have been slow in learning this and perhaps the Negro is no slower than the rest, but his peculiar situation demands that in his case this lesson be learned sooner. Naturally the uncertain economic status even of this picked class makes it difficult for them to spare much time and energy in social reform; compared with their fellows they are rich, but compared with white Americans they are poor, and they can hardly fulfill their duty as the leaders of the Negroes until they are captains of industry over their people as well as richer and wiser. To-day the professional class among them is, compared with other callings, rather over-represented, and all have a struggle to maintain the position they have won.

This class is itself an answer to the question of the ability of the Negro to assimilate American culture. It is a class small in numbers and not sharply differentiated from other classes, although sufficiently so to be easily recognized. Its members are not to be met with in the ordinary assemblages of the Negroes, nor in their usual promenading places. They are largely Philadelphia born, and being descended from the house-servant class, contain many mulattoes. In their assemblies there are evidences of good breeding and taste, so that a foreigner would hardly think of ex-slaves. They are not to be sure people of wide culture and their mental horizon is as limited as that of the first families in a country town. Here and there may be noted, too, some faint trace of careless moral training. On the whole they strike one as sensible, good folks. Their conversation turns on the gossip of similar circles among the Negroes of Washington, Boston and New York; on questions of the day, and, less willingly, on the situation of the Negro. Strangers secure entrance to this circle with difficulty and only by introduction. For an ordinary white person it would be almost impossible to secure introduction even by a friend. Once in a while some well-known citizen meets a company of this class, but it is hard for the average white American to lay aside his patronizing way toward a Negro, and to talk of aught to him but the Negro question; the lack, therefore, of common ground even for conversation makes such meetings rather stiff and not often repeated. Fifty-two of these families keep servants regularly; they live in well-appointed homes, which give evidence of taste and even luxury.18

Something must be said, before leaving this subject, of the amusements of the Negroes. Among the fourth grade and the third, gambling, excursions, balls and cake-walks are the chief amusements. The gambling instinct is widespread, as in all low classes, and, together with sexual looseness, is their greatest vice; it is carried on in clubs, in private houses, in pool-rooms and on the street. Public gambling can be found at a dozen different places every night at full tilt in the Seventh Ward, and almost any stranger can gain easy access. Games of pure chance are preferred to those of skill, and in the larger clubs a sort of three-card monte is the favorite game, played with a dealer who gambles against all comers. In private houses in the slums, cards, beer and prostitutes can always be found. In the public pool-rooms there is some quiet gambling and playing for prizes. For the new comer to the city the only open places of amusement are these pool-rooms and gambling clubs; here are crowds of young fellows, and once started in this company no one can say where they may not end.

The most innocent amusements of this class are the balls and cake-walks, although they are accompanied by much drinking, and are attended by white and black prostitutes. The cake-walk is a rhythmic promenade or slow dance, and when well done is pretty and quite innocent. Excursions are frequent in summer, and are accompanied often by much fighting and drinking.

The mass of the laboring Negroes get their amusement in connection with the churches. There are suppers, fairs, concerts, socials and the like. Dancing is forbidden by most of the churches, and many of the stricter sort would not think of going to balls or theatres. The younger set, however, dance, although the parents seldom accompany them, and the hours kept are late, making it often a dissipation. Secret societies and social clubs add to these amusements by balls and suppers, and there are numbers of parties at private houses. This class also patronizes frequent excursions given by churches and Sunday schools and secret societies; they are usually well conducted, but cost a great deal more than is necessary. The money wasted in excursions above what would be necessary for a day’s outing and plenty of recreation, would foot up many thousand dollars in a season.

In the upper class alone has the home begun to be the centre of recreation and amusement. There are always to be found parties and small receptions, and gatherings at the invitations of musical or social clubs. One large ball each year is usually given, which is strictly private. Guests from out of town are given much social attention.

Among nearly all classes of Negroes there is a large unsatisfied demand for amusement. Large numbers of servant girls and young men have flocked to the city, have no homes, and want places to frequent. The churches supply this need partially, but the institution which will supply this want better and add instruction and diversion, will save many girls from ruin and boys from crime. There is to-day little done in places of public amusement to protect colored girls from designing men. Many of the idlers and rascals of the slums play on the affections of silly servant girls, and either ruin them or lead them into crime, or more often live on a part of their wages. There are many cases of this latter system to be met in the Seventh Ward.

It is difficult to measure amusements in any enlightening way. A count of the amusements reported by the Tribune, the chief colored paper, which reports for a select part of the laboring class, and the upper class, resulted as follows for nine weeks:19

| Parties at homes in honor of visitors | 16 |

| ” ” homes | 11 |

| ” ” ” with dancing | 10 |

| Balls in halls | 10 |

| Concerts in churches | 7 |

| Church suppers, etc. | 7 |

| Weddings | 7 |

| Birthday parties | 7 |

| Lectures and literary entertainments at churches | 6 |

| Card parties | 4 |

| Fairs at churches | 3 |

| Lawn parties and picnics | 3 |

| 91 |

These, of course, are the larger parties in the whole city, and do not include the numerous small church socials and gatherings. The proportions here are largely accidental, but the list is instructive.