31. History of the Negro Church in Philadelphia—We have already followed the history of the rise of the Free African Society, which was the beginning of the Negro Church in the North.1 We often forget that the rise of a church organization among Negroes was a curious phenomenon. The church really represented all that was left of African tribal life, and was the sole expression of the organized efforts of the slaves. It was natural that any movement among freedmen should centre about their religious life, the sole remaining element of their former tribal system. Consequently when, led by two strong men, they left the white Methodist Church, they were naturally unable to form any democratic moral reform association; they must be led and guided, and this guidance must have the religious sanction that tribal government always has. Consequently Jones and Allen, the leaders of the Free African Society, as early as 1791 began regular religious exercises, and at the close of the eighteenth century there were three Negro churches in the city, two of which were independent.2

St. Thomas’ Church has had a most interesting history. It early declared its purpose “of advancing our friends in a true knowledge of God, of true religion, and of the ways and means to restore our long lost race to the dignity of men and of Christians.”3 The church offered itself to the Protestant Episcopal Church and was accepted on condition that they take no part in the government of the general church. Their leader, Absalom Jones, was ordained deacon and priest, and took charge of the church. In 1804 the church established a day school which lasted until 1816.4 In 1849 St. Thomas’ began a series of attempts to gain full recognition in the Church by a demand for delegates to the Church gatherings. The Assembly first declared that it was not expedient to allow Negroes to take part. To this the vestry returned a dignified answer, asserting that “expediency is no plea against the violation of the great principles of charity, mercy, justice and truth.” Not until 1864 was the Negro body received into full fellowship with the Church. In the century and more of its existence St. Thomas’ has always represented a high grade of intelligence, and to-day it still represents the most cultured and wealthiest of the Negro population and the Philadelphia born residents. Its membership has consequently always been small, being 246 in 1794, 427 in 1795, 105 in 1860, and 391 in 1897.5

The growth of Bethel Church, founded by Richard Allen, on South Sixth Street, has been so phenomenal that it belongs to the history of the nation rather than to any one city. From a weekly gathering which met in Allen’s blacksmith shop on Sixth near Lombard, grew a large church edifice; other churches were formed under the same general plan, and Allen, as overseer of them, finally took the title of bishop and ordained other bishops. The Church, under the name of African Methodist Episcopal, grew and spread until in 1890 the organization had 452,725 members, 2,481 churches and $6,468,280 worth of property.6

By 18137 there were in Philadelphia six Negro churches with the following membership:8

| St. Thomas’, P. E | 560 |

| Bethel, A. M. E | 1,272 |

| Zoar, M. E. | 80 |

| Union, A. M. E. | 74 |

| Baptist, Race and Vine Streets | 80 |

| Presbyterian | 300 |

| 2,366 |

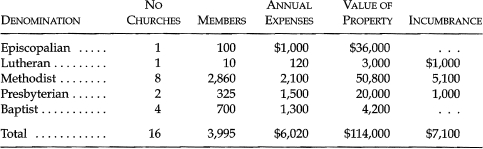

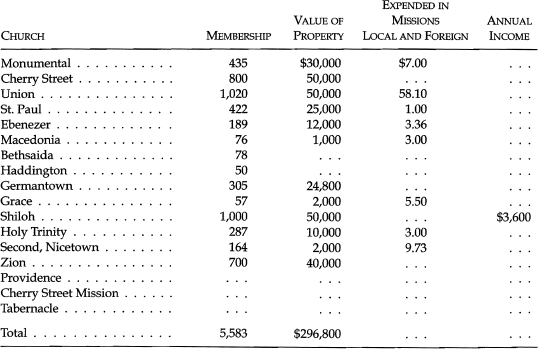

The Presbyterian Church had been founded by two Negro missionaries, father and son, named Gloucester, in 1807.9 The Baptist Church was founded in 1809. The inquiry of 1838 gives these statistics of churches:

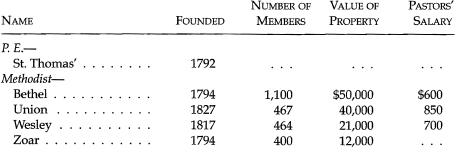

Three more churches were added in the next ten years, and then a reaction followed.10 By 1867 there were in all probability nearly twenty churches, of which we have statistics of seventeen:11

STATISTICS OF NEGRO CHURCHES, 1867

Since the war the growth of Negro churches has been by bounds, there being twenty-five churches and missions in 1880, and fifty-five in 1897.

So phenomenal a growth as this here outlined means more than the establishment of many places of worship. The Negro is, to be sure, a religious creature—most primitive folk are—but his rapid and even extraordinary founding of churches is not due to this fact alone, but is rather a measure of his development, an indication of the increasing intricacy of his social life and the consequent multiplication of the organ which is the function of his group life—the church. To understand this let us inquire into the function of the Negro church.

32. The Function of the Negro Church—The Negro church is the peculiar and characteristic product of the transplanted African, and deserves especial study. As a social group the Negro church may be said to have antedated the Negro family on American soil; as such it has preserved, on the one hand, many functions of tribal organization, and on the other hand, many of the family functions. Its tribal functions are shown in its religious activity, its social authority and general guiding and co-ordinating work; its family functions are shown by the fact that the church is a centre of social life and intercourse; acts as newspaper and intelligence bureau, is the centre of amusements—indeed, is the world in which the Negro moves and acts. So far-reaching are these functions of the church that its organization is almost political. In Bethel Church, for instance, the mother African Methodist Episcopal Church of America, we have the following officials and organizations:

Or to put it differently, here we have a mayor, appointed from without, with great administrative and legislative powers, although well limited by long and zealously cherished custom; he acts conjointly with a select council, the trustees, a board of finance, composed of stewards and stewardesses, a common council of committees and, occasionally, of all church members. The various functions of the church are carried out by societies and organizations. The form of government varies, but is generally some form of democracy closely guarded by custom and tempered by possible and not infrequent secession.

The functions of such churches in order of present emphasis are:

1. The annual budget is of first importance, because the life of the organization depends upon it. The amount of expenditure is not very accurately determined beforehand, although its main items do not vary much. There is the pastor’s salary, the maintenance of the building, light and heat, the wages of a janitor, contributions to various church objects, and the like, to which must be usually added the interest on some debt. The sum thus required varies in Philadelphia from $200 to $5,000. A small part of this is raised by a direct tax on each member. Besides this, voluntary contributions by members, roughly gauged according to ability, are expected, and a strong public opinion usually compels payment. Another large source of revenue is the collection after the sermons on Sunday, when, amid the reading of notices and a subdued hum of social intercourse, a stream of givers walk to the pulpit and place in the hands of the trustee or steward in charge a contribution, varying from a cent to a dollar or more. To this must be added the steady revenue from entertainments, suppers, socials, fairs, and the like. In this way the Negro churches of Philadelphia raise nearly $100,000 a year. They hold in real estate $900,000 worth of property, and are thus no insignificant element in the economics of the city.

2. Extraordinary methods are used and efforts made to maintain and increase the membership of the various churches. To be a popular church with large membership means ample revenues, large social influence and a leadership among the colored people unequaled in power and effectiveness. Consequently people are attracted to the church by sermons, by music and by entertainments; finally, every year a revival is held, at which considerable numbers of young people are converted. All this is done in perfect sincerity and without much thought of merely increasing membership, and yet every small church strives to be large by these means and every large church to maintain itself or grow larger. The churches thus vary from a dozen to a thousand members.

3. Without wholly conscious effort the Negro church has become a centre of social intercourse to a degree unknown in white churches even in the country. The various churches, too, represent social classes. At St. Thomas’ one looks for the well-to-do Philadelphians, largely descendants of favorite mulatto house servants, and consequently well-bred and educated, but rather cold and reserved to strangers or newcomers; at Central Presbyterian one sees the older, simpler set of respectable Philadelphians with distinctly Quaker characteristics—pleasant but conservative; at Bethel may be seen the best of the great laboring class—steady, honest people, well dressed and well fed, with church and family traditions; at Wesley will be found the new arrivals, the sight-seers and the strangers to the city—hearty and easy-going people, who welcome all comers and ask few questions; at Union Baptist one may look for the Virginia servant girls and their young men; and so on throughout the city. Each church forms its own social circle, and not many stray beyond its bounds. Introductions into that circle come through the church, and thus the stranger becomes known. All sorts of entertainments and amusements are furnished by the churches: concerts, suppers, socials, fairs, literary exercises and debates, cantatas, plays, excursions, picnics, surprise parties, celebrations. Every holiday is the occasion of some special entertainment by some club, society or committee of the church; Thursday afternoons and evenings, when the servant girls are free, are always sure to have some sort of entertainment. Sometimes these exercises are free, sometimes an admission fee is charged, sometimes refreshments or articles are on sale. The favorite entertainment is a concert with solo singing, instrumental music, reciting, and the like. Many performers make a living by appearing at these entertainments in various cities, and often they are persons of training and ability, although not always. So frequent are these and other church exercises that there are few Negro churches which are not open four to seven nights in a week and sometimes one or two afternoons in addition.

Perhaps the pleasantest and most interesting social intercourse takes place on Sunday; the weary week’s work is done, the people have slept late and had a good breakfast, and sally forth to church well dressed and complacent. The usual hour of the morning service is eleven, but people stream in until after twelve. The sermon is usually short and stirring, but in the larger churches elicits little esponse other than an “Amen” or two. After the sermon the social features begin; notices on the various meetings of the week are read, people talk with each other in subdued tones, take their contributions to the altar, and linger in the aisles and corridors long after dismission to laugh and chat until one or two o’clock. Then they go home to good dinners. Sometimes there is some special three o’clock service, but usually nothing save Sunday school, until night. Then comes the chief meeting of the day; probably ten thousand Negroes gather every Sunday night in their churches. There is much music, much preaching, some short addresses; many strangers are there to be looked at; many beaus bring out their belles, and those who do not gather in crowds at the church door and escort the young women home. The crowds are usually well behaved and respectable, though rather more jolly than comports with a puritan idea of church services.

In this way the social life of the Negro centres in his church—baptism, wedding and burial, gossip and courtship, friendship and intrigue—all lie in these walls. What wonder that this central club house tends to become more and more luxuriously furnished, costly in appointment and easy of access!

4. It must not be inferred from all this that the Negro is hypocritical or irreligious. His church is, to be sure, a social institution first, and religious afterwards, but nevertheless, its religious activity is wide and sincere. In direct moral teaching and in setting moral standards for the people, however, the church is timid, and naturally so, for its constitution is democracy tempered by custom. Negro preachers are often condemned for poor leadership and empty sermons, and it is said that men with so much power and influence could make striking moral reforms. This is but partially true. The congregation does not follow the moral precepts of the preacher, but rather the preacher follows the standard of his flock, and only exceptional men dare seek to change this. And here it must be remembered that the Negro preacher is primarily an executive officer, rather than a spiritual guide. If one goes into any great Negro church and hears the sermon and views the audience, one would say: either the sermon is far below the calibre of the audience, or the people are less sensible than they look; the former explanation is usually true. The preacher is sure to be a man of executive ability, a leader of men, a shrewd and affable president of a large and intricate corporation. In addition to this he may be, and usually is, a striking elocutionist; he may also be a man of integrity, learning, and deep spiritual earnestness; but these last three are sometimes all lacking, and the last two in many cases. Some signs of advance are here manifest: no minister of notoriously immoral life, or even of bad reputation, could hold a large church in Philadelphia without eventual revolt. Most of the present pastors are decent, respectable men; there are perhaps one or two exceptions to this, but the exceptions are doubtful, rather than notorious. On the whole then, the average Negro preacher in this city is a shrewd manager, a respectable man, a good talker, a pleasant companion, but neither learned nor spiritual, nor a reformer.

The moral standards are therefore set by the congregations, and vary from church to church in some degree. There has been a slow working toward a literal obeying of the puritan and ascetic standard of morals which Methodism imposed on the freedmen; but condition and temperament have modified these. The grosser forms of immorality, together with theatre-going and dancing, are specifically denounced; nevertheless, the precepts against specific amusements are often violated by church members. The cleft between denominations is still wide, especially between Methodists and Baptists. The sermons are usually kept within the safe ground of a mild Calvinism, with much insistence on Salvation, Grace, Fallen Humanity and the like.

The chief function of these churches in morals is to conserve old standards and create about them a public opinion which shall deter the offender. And in this the Negro churches are peculiarly successful, although naturally the standards conserved are not as high as they should be.

5. The Negro churches were the birthplaces of Negro schools and of all agencies which seek to promote the intelligence of the masses; and even to-day no agency serves to disseminate news or information so quickly and effectively among Negroes as the church. The lyceum and lecture here still maintain a feeble but persistent existence, and church newspapers and books are circulated widely. Night schools and kindergartens are still held in connection with churches, and all Negro celebrities, from a bishop to a poet like Dunbar, are introduced to Negro audiences from the pulpits.

6. Consequently all movements for social betterment are apt to centre in the churches. Beneficial societies in endless number are formed here; secret societies keep in touch; co-operative and building associations have lately sprung up; the minister often acts as an employment agent; considerable charitable and relief work is done and special meetings held to aid special projects.12 The race problem in all its phases is continually being discussed, and, indeed, from this forum many a youth goes forth inspired to work.

Such are some of the functions of the Negro church, and a study of them indicates how largely this organization has come to be an expression of the organized life of Negroes in a great city.

33. The Present Condition of the Churches—The 2,441 families of the Seventh Ward were distributed among the various denominations, in 1896, as follows:

| FAMILIES | |

| Methodists | 842 |

| Baptists | 577 |

| Episcopalians | 156 |

| Presbyterians | 74 |

| Catholic | 69 |

| Shakers | 2 |

| Unconnected and unknown | 721 |

| 2,441 |

Probably half of the “unconnected and unknown” habitually attend church.

In the city at large the Methodists have a decided majority, followed by the Baptists, and further behind, the Episcopalians. Starting with the Methodists, we find three bodies: the African Methodist Episcopal, founded by Allen, the A. M. E. Zion, which sprung from a secession of Negroes from white churches in New York in the eighteenth century; and the M. E. Church, consisting of colored churches belonging to the white Methodist Church, like Zoar.

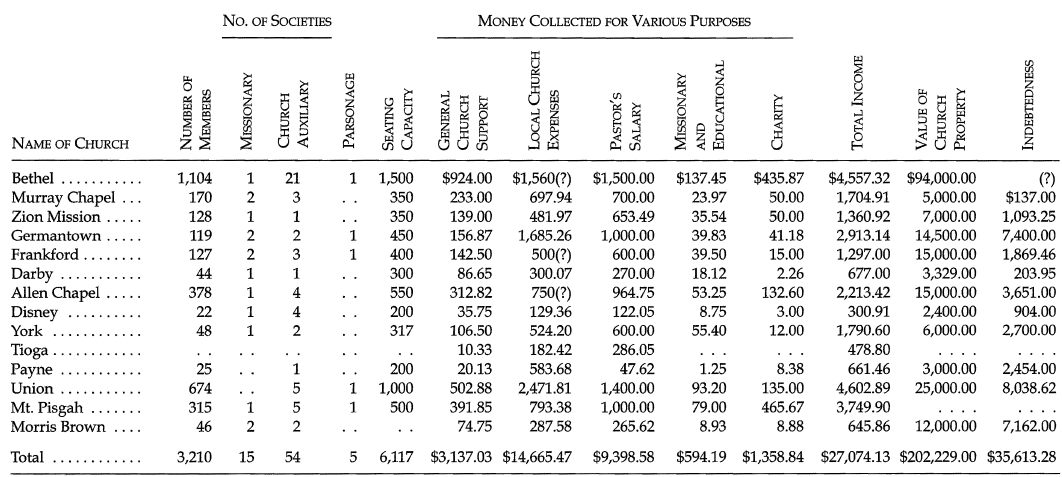

The A. M. E. Church is the largest body and had, in 1897, fourteen churches and missions in the city, with a total membership of 3,210, and thirteen church edifices, seating 6,117 persons. These churches collected during the year, $27,074.13. Their property is valued at $202,229 on which there is a mortgage indebtedness of $30,000 to $50,000. Detailed statistics are given in the table on the next page.

These churches are pretty well organized, and are conducted with vim and enthusiasm. This arises largely from their system. Their bishops have been in some instances men of piety and ability like the late Daniel A. Payne. In other cases they have fallen far below this standard; but they have always been men of great influence, and had a genius for leadership—else they would not have been bishops. They have large powers of appointment and removal in the case of pastors, and thus each pastor, working under the eye of an inspiring chief, strains every nerve to make his church a successful organization. The bishop is aided by several presiding elders, who are traveling inspectors and preachers, and give advice as to appointments. This system results in great unity and power; the purely spiritual aims of the church, to be sure, suffer somewhat, but after all this peculiar organism is more than a church, it is a government of men.

The headquarters of the A. M. E. Church are in Philadelphia. Their publishing house, at Seventh and Pine, publishes a weekly paper and a quarterly review, besides some books, such as hymnals, church disciplines, short treatises, leaflets and the like. The receipts of this establishment in 1897 were $16,058.26, and its expenditures $14,119.15. Its total outfit and property is valued at $45,513.64, with an indebtedness of $14,513.64.

An episcopal residence for the bishop of the district has recently been purchased on Belmont avenue. The Philadelphia Conference disbursed from the general church funds in 1897, $985 to superannuated ministers, and $375 to widows of ministers. Two or three women missionaries visited the sick during the year and some committees of the Ladies’ Mission Society worked to secure orphans’ homes.13 Thus throughout the work of this church there is much evidence of enthusiasm and persistent progress.14

There are three churches in the city representing the A. M. E. Zion connection. They are:

| Wesley | Fifteenth and Lombard Sts. |

| Mount Zion | Fifty-fifth above Market St. |

| Union | Ninth St. and Girard Ave. |

No detailed statistics of these churches are available; the last two are small, the first is one of the largest and most popular in the city; the pastor receives $1500 a year and the total income of the church is between $4,000 and $5,000. It does considerable charitable work among its aged members, and supports a large sick and death benefit society. Its property is worth at least $25,000.

Two other Methodist churches of different denominations are: Grace U. A. M. E., Lombard street, above Fifteenth; St. Matthew Methodist Protestant, Fifty-eighth and Vine streets. Both these churches are small, although the first has a valuable piece of property.

A. M. E. CHURCHES IN PHILADELPHIA, 1897

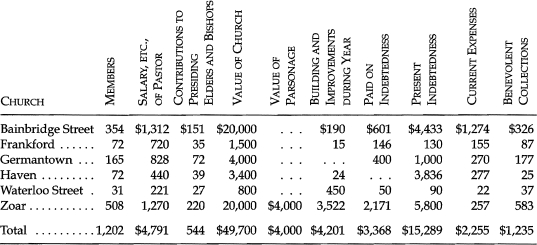

The Methodist Episcopal Church has six organizations in the city among the Negroes; they own church property valued at $53,700, have a total membership of 1,202, and an income of $16,394 in 1897. Of this total income, $1,235, or 7½ per cent, was given for benevolent enterprises. These churches are quiet and well conducted, and although not among the most popular churches, have nevertheless a membership of old and respected citizens.

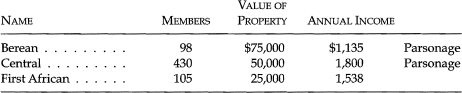

COLORED M. E. CHURCHES IN PHILADELPHIA, 1897

There were in 1896 seventeen Baptist churches in Philadelphia, holding property valued at more than $300,000, having six thousand members, and an annual income of, probably, $30,000 to $35,000. One of the largest churches has in the last five years raised between $17,000 and $18,000.

COLORED BAPTIST CHURCHES OF PHILADELPHIA, 1896

The Baptists are strong in Philadelphia, and own many large and attractive churches, such as, for instance, the Union Baptist Church, on Twelfth street; Zion Baptist, in the northern part of the city; Monumental, in West Philadelphia, and the staid and respectable Cherry Street Church. These churches as a rule have large membership. They are, however, quite different in spirit and methods from the Methodists; they lack organization, and are not so well managed as business institutions. Consequently statistics of their work are very hard to obtain, and indeed in many cases do not even exist for individual churches. On the other hand, the Baptists are peculiarly clannish and loyal to their organization, keep their pastors a long time, and thus each church gains an individuality not noticed in Methodist churches. If the pastor is a strong, upright character, his influence for good is marked. At the same time, the Baptists have in their ranks a larger percentage of illiteracy than probably any other church, and it is often possible for an inferior man to hold a large church for years and allow it to stagnate and retrograde. The Baptist policy is extreme democracy applied to church affairs, and no wonder that this often results in a pernicious dictatorship. While many of the Baptist pastors of Philadelphia are men of ability and education, the general average is below that of the other churches—a fact due principally to the ease with which one can enter the Baptist ministry.15 These churches support a small publishing house in the city, which issues a weekly paper. They do some charitable work, but not much.16

There are three Presbyterian churches in the city:

Central Church is the oldest of these churches and has an interesting history. It represents a withdrawal from the First African Presbyterian Church in 1844. The congregation first worshiped at Eighth and Carpenter streets, and in 1845 purchased a lot at Ninth and Lombard, where they still meet in a quiet and respectable house of worship. Their 430 members include some of the oldest and most respectable Negro families of the city. Probably if the white Presbyterians had given more encouragement to Negroes, this denomination would have absorbed the best elements of the colored population; they seem, however, to have shown some desire to be rid of the blacks, or at least not to increase their Negro membership in Philadelphia to any great extent. Central Church is more nearly a simple religious organization than most churches; it listens to able sermons, but does little outside its own doors.17

Berean Church is the work of one man and is an institutional church. It was formerly a mission of Central Church and now owns a fine piece of property bought by donations contributed by whites and Negroes, but chiefly by the former. The conception of the work and its carrying out, however, is due to Negroes. This church conducts a successful Building and Loan Association, a kindergarten, a medical dispensary and a seaside home, beside the numerous church societies. Probably no church in the city, except the Episcopal Church of the Crucifixion, is doing so much for the social betterment of the Negro.18 The First African is the oldest colored church of this denomination in the city.

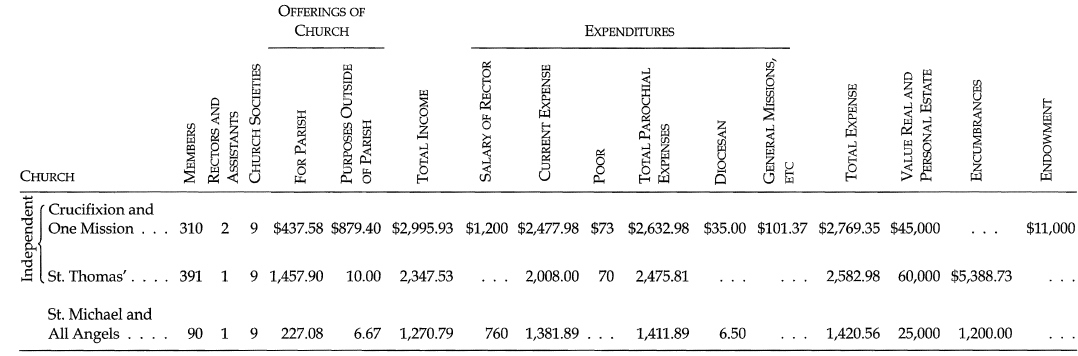

The Episcopal Church has, for Negro congregations, two independent churches, two churches dependent on white parishes, and four missions and Sunday schools. Statistics of three of these are given in the table on page 153.

The Episcopal churches receive more outside help than others and also do more general mission and rescue work. They hold $150,000 worth of property, have 900–1,000 members and an annual income of $7,000 to $8,000. They represent all grades of the colored population. The oldest of the churches is St. Thomas’. Next comes the Church of the Crucifixion, over fifty years old and perhaps the most effective church organization in the city for benevolent and rescue work. It has been built up virtually by one Negro, a man of sincerity and culture, and of peculiar energy. This church carries on regular church work at Bainbridge and Eighth and at two branch missions; it helps in the Fresh Air Fund, has an ice mission, a vacation school of thirty-five children, and a parish visitor. It makes an especial feature of good music with its vested choir. One or two courses of University Extension lectures are held here each year, and there is a large beneficial and insurance society in active operation, and a Home for the Homeless on Lombard street. This church especially reaches after a class of neglected poor whom the other colored churches shun or forget and for whom there is little fellowship in white churches. The rector says of this work:

“As I look back over nearly twenty years of labor in one parish, I see a great deal to be devoutly thankful for. Here are people struggling from the beginning of one year to another, without ever having what can be called the necessaries of life. God alone knows what a real struggle life is to them. Many of them must always be ‘moving on,’ because they cannot pay the rent or meet other obligations.

“I have just visited a family of four, mother and three children. The mother is too sick to work. The eldest girl will work when she can find something to do. But the rent is due, and there is not a cent in the house. This is but a sample. How can such people support a church of their own? To many such, religion often becomes doubly comforting. They seize eagerly on the promises of a life where these earthly distresses will be forever absent.

“If the other half only knew how this half is living—how hard and dreary, and often hopeless, life is—the members of the more favored half would gladly help to do all they could to have the gospel freely preached to those whose lives are so devoid of earthly comforts.

“Twenty or thirty thousand dollars (and that is not much), safely invested, would enable the parish to do a work that ought to be done and yet is not being done at present. The poor could then have the gospel preached to them in a way that it is not now being preached.”

The Catholic church has in the last decade made great progress in its work among Negroes and is determined to do much in the future. Its chief hold upon the colored people is its comparative lack of discrimination. There is one Catholic church in the city designed especially for Negro work—St. Peter Clavers at Twelfth and Lombard—formerly a Presbyterian church; recently a parish house has been added. The priest in charge estimates that 400 or 500 Negroes regularly attend Catholic churches in various parts of the city. The Mary Drexel Home for Colored Orphans is a Catholic institution near the city which is doing much work. The Catholic church can do more than any other agency in humanizing the intense prejudice of many of the working class against the Negro, and signs of this influence are manifest in some quarters.

COLORED PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCHES IN PHILADELPHIA*, 1897

*Besides these, there are the following Churches, from which statistics were not obtained: St. Mark’s, Zion Sunday school, St. Faith’s Mission, and St. Simon’s Chapel. The first is supported mainly by a white parish, and has a new building; the second and third are small Missions; the fourth is a promising outgrowth of the Church of the Crucifixion.

We have thus somewhat in detail reviewed the work of the chief churches. There are beside these continually springing up and dying a host of little noisy missions which represent the older and more demonstrative worship. A description of one applies to nearly all; take for instance one in the slums of the Fifth Ward:

“The tablet in the gable of this little church bears the date 1837. For sixty years it has stood and done its work in the narrow lane. What its history has been all this time it is difficult to find out, for no records are on hand, and no one is here to tell the tale.

“The few last months of the old order was something like this: It was in the hands of a Negro congregation. Several visits were paid to the church, and generally a dozen people were found there. After a discourse by a very illiterate preacher, hymns were sung, having many repetitions of senseless sentiment and exciting cadences. It took about an hour to work up the congregation to a fervor aimed at. When this was reached a remarkable scene presented itself. The whole congregation pressed forward to an open space before the pulpit, and formed a ring. The most excitable of their number entered the ring, and with clapping of hands and contortions led the devotions. Those forming the ring joined in the clapping of hands and wild and loud singing, frequently springing into the air, and shouting loudly. As the devotions proceeded, most of the worshipers took off their coats and vests and hung them on pegs on the wall. This continued for hours, until all were completely exhausted, and some had fainted and been stowed away on benches or the pulpit platform. This was the order of things at the close of sixty years’ history. * * * When this congregation vacated the church, they did so stealthily, under cover of darkness, removed furniture not their own, including the pulpit, and left bills unpaid.”19

There are dozens of such little missions in various parts of Philadelphia, led by wandering preachers. They are survivals of the methods of worship in Africa and the West Indies. In some of the larger churches noise and excitement attend the services, especially at the time of revival or in prayer meetings. For the most part, however, these customs are dying away.

To recapitulate, we have in Philadelphia fifty-five Negro churches with 12,845 members owning $907,729 worth of property with an annual income of at least $94,968. And these represent the organized efforts of the race better than any other organizations. Second to them however come the secret and benevolent societies, which we now consider.

34. Secret and Beneficial Societies, and Co-operative Business—The art of organization is the one hardest for the freedman to learn, and the Negro shows his greatest deficiency here; whatever success he has had has been shown most conspicuously in his church organizations, where the religious bond greatly facilitated union. In other organizations where the bond was weaker his success has been less. From early times the precarious economic condition of the free Negroes led to many mutual aid organizations. They were very simple in form: an initiation fee of small amount was required, and small regular payments; in case of sickness, a weekly stipend was paid, and in case of death the members were assessed to pay for the funeral and help the widow. Confined to a few members, all personally known to each other, such societies were successful from the beginning. We hear of them in the eighteenth century, and by 1838 there were 100 such small groups, with 7,448 members, in the city. They paid in $18,851, gave $14,172 in benefits, and had $10,023 on hand. Ten years later about eight thousand members belonged to 106 such societies. Seventy-six of these had a total membership of 5,187. They contributed usually 25 cents to 37½ cents a month; the sick received $1.50 to $3.00 a week, and death benefits of $10.00 to $20.00 were allowed. The income of these seventy-six societies was $16,814.23; 681 families were assisted.20

These societies have since been superceded to some extent by other organizations; they are still so numerous, however, that it is impractical to catalogue all of them; there are probably several hundred of various kinds in the city.

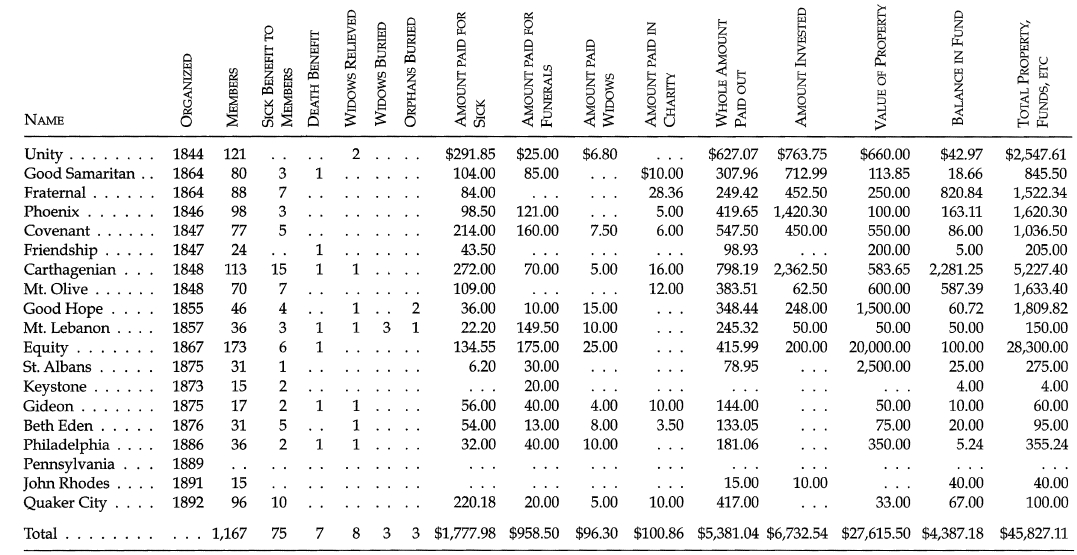

To these were early added the secret societies, which naturally had great attraction for Negroes. A Boston lodge of black Masons received a charter direct from England, and independent orders of Odd Fellows, Knights of Pythias, etc., grew up. During the time that Negroes were shut out of the public libraries there were many literary associations with libraries. These have now disappeared. Outside the churches the most important organizations among Negroes to-day are: Secret societies, beneficial societies, insurance societies, cemeteries, building and loan associations, labor unions, homes of various sorts and political clubs. The most powerful and flourishing secret order is that of the Odd Fellows, which has two hundred thousand members among American Negroes. In Philadelphia there are 19 lodges with a total membership of 1,188, and $46,000 worth of property. Detailed statistics are in the table on page 156.21

This order owns two halls in the city worth perhaps $40,000. One is occupied by the officers of the Grand Lodge, which employs several salaried officials and clerks. The order conducts a newspaper called the Odd Fellows’ Journal.

There are 19 lodges of Masons in the city, 6 chapters, 5 commanderies, 3 of the Scottish Rite, and 1 drill corp. The Masons are not so well organized and conducted as the Odd Fellows, and detailed statistics of their lodges are not available. They own two halls worth at least $50,000, and probably distribute not less than $3,000 to $4,000 annually in benefits.

Beside these chief secret orders there are numerous others, such as the American Protestant Association, which has many members, the Knights of Pythias, the Galilean Fishermen, the various female orders attached to these, and a number of others. It is almost impossible to get accurate statistics of all these orders, and any estimate of their economic activity is liable to considerable error. However, from general observation and the available figures, it seems fairly certain that at least four thousand Negroes belong to secret orders, and that these orders annually collect at least $25,000, part of which is paid out in sick and death benefits, and part invested. The real estate, personal property and funds of these orders amount to no less than $125,000.

COLORED ODD FELLOWS’ LODGES IN PHILADELPHIA, 1896

The function of the secret society is partly social intercourse and partly insurance. They furnish pastime from the monotony of work, a field for ambition and intrigue, a chance for parade, and insurance against misfortune. Next to the church they are the most popular organizations among Negroes.

Of the beneficial societies we have already spoken in general. A detailed account of a few of the larger and more typical organizations will now suffice. The Quaker City Association is a sick and death benefit society, seven years old, which confines its membership to native Philadelphians. It has 280 members and distributes $1,400 to $1,500 annually. The Sons and Daughters of Delaware is over fifty years old. It has 106 members, and owns $3,000 worth of real estate. The Fraternal Association was founded in 1861; it has 86 members, and distributes about $300 a year. It “was formed for the purpose of relieving the wants and distresses of each other in the time of affliction and death, and for the furtherance of such benevolent views and objects as would tend to establish and maintain a permanent and friendly intercourse among them in their social relations in life.” The Sons of St. Thomas was founded in 1823 and was originally confined to members of St. Thomas’ Church. It was formerly a large organization, but now has 80 members, and paid out in 1896, $416 in relief. It has $1,500 invested in government bonds. In addition to these there is the Old Men’s Association, the Female Cox Association, the Sons and Daughters of Moses, and a large number of other small societies.

There is arising also a considerable number of insurance societies, differing from the beneficial in being conducted by directors. The best of these are the Crucifixion connected with the Church of the Crucifixion, and the Avery, connected with Wesley A. M. E. Z. Church; both have a large membership and are well conducted. Nearly every church is beginning to organize one or more such societies, some of which in times past have met disaster by bad management. The True Reformers of Virginia, the most remarkable Negro beneficial organization yet started, has several branches here. Beside these there are numberless minor societies, as the Alpha Relief, Knights and Ladies of St. Paul, the National Co-operative Society, Colored Women’s Protective Association, Loyal Beneficial, etc. Some of these are honest efforts and some are swindling imitations of the pernicious white petty insurance societies.

There are three building and loan associations conducted by Negroes. Some of the directors in one are white, all the others are colored. The oldest association is the Century, established October 26, 1886. Its board of directors is composed of teachers, upholsterers, clerks, restaurant keepers and undertakers, and it has had marked success. Its income for 1897 was about $7,000. It has $25,000 in loans outstanding.

The Berean Building and Loan Association was established in 1888 in connection with Berean Presbyterian Church; 13 of the 19 officers and directors are colored. Its income for 1896 was nearly $30,000, and it had $60,000 in loans; 43 homes have been bought through this association.22

The Pioneer Association is composed entirely of Negroes, the directors being caterers, merchants and upholsterers. It was founded in 1888 and has an office on Pine street. Its receipts in 1897 were $9,000, and it had about $20,000 in loans. Nine homes are at present being bought in this association.

There are arising some loan associations to replace the pawn-shops and usurers to some extent. The Small Loan Association, for instance, was founded in 1891, and has the following report for 1898:

| Shares sold ................................ $1,144.00 |

| Assessments on shares ...................... 114.40 |

| Repaid loans ............................... 4,537.50 |

| Interest ................................... 417.06 |

| Cash in treasury ............................ 275.54 |

| Dividends paid ............................ 222.67 |

| Loans made ............................... 4,626.75 |

| Expenses .................................. 82.02 |

The Conservative is a similar organization, consisting of ten members.

This account has attempted to touch only the chief and characteristic organizations, and makes no pretensions to completeness. It shows, however, how intimately bound together the Negroes of Philadelphia are. These associations are largely experiments, and as such, are continually reaching out to new fields. The latest ventures are toward labor unions, co-operative stores and newspapers. There are the following labor unions, among others: The Caterers’ Club, the Private Waiters’ Association, the Coachmen’s Association, the Hotel Brotherhood (of waiters), the Cigar-makers’ Union (white and colored), the Hod-Carriers’ Union, the Barbers’ Union, etc.

Of the Caterers’ Club we have already heard.23 The Private Waiters’ Association is an old beneficial order with well-to-do members. The private waiter is really a skilled workman of high order, and used to be well paid. Next to the guild of caterers he ranked as high as any class of Negro workmen before the war—indeed the caterer was but a private waiter further developed. Consequently this labor union is still jealous and exclusive and contains some members long retired from active work. The Coachmen’s Association is a similar society; both these organizations have a considerable membership, and make sick and death benefits and social gatherings a feature. The Hotel Brotherhood is a new society of hotel waiters and is conducted by young men on the lines of the regular trades unions, with which it is more or less affiliated in many cities. It has some relief features and considerable social life. It strives to open and keep open work for colored waiters and often arranges to divide territory with whites, or to prevent one set from supplanting the other. The Cigar-makers’ Union is a regular trades union with both white and Negro members. It is the only union in Philadelphia where Negroes are largely represented. No friction is apparent. The Hod-Carriers’ Union is large and of considerable age but does not seem to be very active. A League of Colored Mechanics was formed in 1897 but did not accomplish anything. There was before the war a league of this sort which flourished, and there undoubtedly will be attempts of this sort in the future until a union is effected.24

The two co-operative grocery stores, and the caterers’ supply store have been mentioned.25 There was a dubious attempt in 1896 to organize a co-operative tin-ware store which has not yet been successful.26

With all this effort and movement it is natural that the Negroes should want some means of communication. This they have in the following periodicals conducted wholly by Negroes:

A. M. E. Church Review, quarterly, 8vo, about ninety-five pages.

Christian Recorder, eight-page weekly newspaper. (Both these are organs of the A. M. E. Church.)

Baptist Christian Banner, four-page weekly newspaper. (Organ of the Baptists.)

Odd Fellows’ Journal, eight-page weekly newspaper. (Organ of Odd Fellows.)

Weekly Tribune, eight-page weekly newspaper, seventeen years established.

The Astonisher, eight-page weekly newspaper (Germantown).

The Standard-Echo, four-page weekly newspaper (since suspended).

The Tribune is the chief news sheet and is filled generally with social notes of all kinds, and news of movements among Negroes over the country. Its editorials are usually of little value chiefly because it does not employ a responsible editor. It is in many ways however an interesting paper and represents pluck and perseverance on the part of its publisher. The Astonisher and Standard Echo are news sheets. The first is bright but crude. The Recorder, Banner and Journal are chiefly filled with columns of heavy church and lodge news. The Review has had an interesting history and is probably the best Negro periodical of the sort published; it is often weighted down by the requirements of church politics, and compelled to publish some trash written by aspiring candidates for office; but with all this it has much solid matter and indicates the trend of thought among Negroes to some extent. It has greatly improved in the last few years. Many Negro newspapers from other cities circulate here and widen the feeling of community among the colored people of the city.

One other kind of organization has not yet been mentioned, the political clubs, of which there are probably fifty in the city. They will be considered in another chapter.

35. Institutions—The chief Negro institutions of the city are: The Home for Aged and Infirmed Colored Persons, the Douglass Hospital and Training School, the Woman’ s Exchange and Girls’ Home, three cemetery companies, the Home for the Homeless, the special schools, as the Institute for Colored Youth, the House of Industry, Raspberry street schools and Jones’s school for girls, the Y.M.C.A., and University Extension Centre.

The Home for the Aged, situated at the corner of Girard and Belmont avenues, was founded by a Negro lumber merchant, Steven Smith, and is conducted by whites and Negroes. It is one of the best institutions of the kind; its property is valued at $400,000, and it has an annual income of $20,000. It has sheltered 558 old people since its foundation in 1864.

The Douglass Memorial Hospital and Training School is a curious example of the difficult position of Negroes: for years nearly every hospital in Philadelphia has sought to exclude Negro women from the course in nurse-training, and no Negro physician could have the advantage of hospital practice. This led to a movement for a Negro hospital; such a movement however was condemned by the whites as an unnecessary addition to a bewildering number of charitable institutions; by many of the best Negroes as a concession to prejudice and a drawing of the color line. Nevertheless the promoters insisted that colored nurses were efficient and needed training, that colored physicians needed a hospital, and that colored patients wished one. Consequently the Douglass Hospital has been established and its success seems to warrant the effort.27

The total income for the year 1895–96 was $4,656.31; sixty-one patients were treated during the year, and thirty-two operations performed; 987 out-patients were treated. The first class of nurses was graduated in 1897.

The Woman’s Exchange and Girls’ Home is conducted by the principal of the Institute for Colored Youth at 756 South Twelfth street. The exchange is open at stated times during the week, and various articles are on sale. Cheap lodging and board is furnished for a few school girls and working girls. So far the work of the exchange has been limited but it is slowly growing, and is certainly a most deserving venture.28

The exclusion of Negroes from cemeteries has, as before mentioned, led to the organization of three cemetery companies, two of which are nearly fifty years old. The Olive holds eight acres of property in the Twenty-fourth Ward, claimed to be worth $100,000. It has 900 lot owners; the Lebanon holds land in the Thirty-sixth Ward, worth at least $75,000. The Merion is a new company which owns twenty-one acres in Montgomery County, worth perhaps $30,000. These companies are in the main well-conducted, although the affairs of one are just now somewhat entangled.

The Home for the Homeless is a refuge and home for the aged connected with the Church of the Crucifixion. It is supported largely by whites but not entirely. It has an income of about $500. During 1896, 1,108 lodgings were furnished to ninety women, 8,384 meals given to inmates, 2,705 to temporary lodgers, 2,078 to transients, and 812 to invalids.

The schools have all been mentioned before. The Young Men’s Christian Association has had a checkered history, chiefly as it would seem from the wrong policy pursued; there is in the city a grave and dangerous lack of proper places of amusement and recreation for young men. To fill this need a properly conducted Young Men’s Christian Association, with books and newspapers, baths, bowling alleys and billiard tables, conversation rooms and short, interesting religious services is demanded; it would cost far less than it now costs the courts to punish the petty misdemeanors of young men who do not know how to amuse themselves. Instead of such an institution however the Colored Y. M. C. A. has been virtually an attempt to add another church to the numberless colored churches of the city, with endless prayer-meetings and loud gospel hymns, in dingy and uninviting quarters. Consequently the institution is now temporarily suspended. It had accomplished some good work by its night schools, and social meetings.

Since the organization of the Bainbridge Street University Extension Centre, May 10, 1895, lectures have been delivered at the Church of the Crucifixion, Eighth and Bainbridge streets, by Rev. W. Hudson Shaw, on English History; by Thomas Whitney Surette, on the Development of Music; by Henry W. Elson, on American History, and by Hilaire Belloc, on Napoleon. Each of these lecturers, except Mr. Belloc, has given a course of six lectures on the subject stated, and classes have been held in connection with each course. The attendance has been above the average as compared with other Centres in the city.

Beside these efforts there are various embryonic institutions: A day nursery in the Seventh Ward by the Woman’s Missionary Society, a large organization which does much charitable work; an industrial school near the city, etc. There are, too, many institutions conducted by whites for the benefit of Negroes, which will be mentioned in another place.

Much of the need for separate Negro institutions has in the last decade disappeared, by reason of the opening of the doors of the public institutions to colored people. There are many Negroes who on this account strongly oppose efforts which they fear will tend to delay further progress in these lines. On the other hand, thoughtful men see that invaluable training and discipline is coming to the race through these institutions and organizations, and they encourage the formation of them.

36. The Experiment of Organization—Looking back over the field which we have thus reviewed—the churches, societies, unions, attempts at business cooperation, institutions and newspapers—it is apparent that the largest hope for the ultimate rise of the Negro lies in this mastery of the art of social organized life. To be sure, compared with his neighbors, he has as yet advanced but a short distance; we are apt to condemn this lack of unity, the absence of carefully planned and laboriously executed effort among these people, as a voluntary omission—a bit of carelessness. It is far more than this, it is lack of social education, of group training, and the lack can only be supplied by a long, slow process of growth. And the chief value of the organizations studied is that they are evidences of growth. Of actual accomplishment they have, to be sure, something to show, but nothing to boast of inordinately. The churches are far from ideal associations for fostering the higher life—rather they combine too often intrigue, extravagance and show, with all their work, saving and charity; their secret societies are often diverted from their better ends by scheming and dishonest officers, and by the temptation of tinsel and braggadocio; their beneficial associations, along with all their good work, have an unenviable record of business inefficiency and internal dissension. And yet all these and the other agencies have accomplished much, and their greatest accomplishment is stimulation of effort to further and more effective organization among a disorganized and headless host. All this world of co-operation and subordination into which the white child is in most cases born is, we must not forget, new to the slave’s sons. They have been compelled to organize before they knew the meaning of organization; to co-operate with those of their fellows to whom co-operation was an unknown term; to fix and fasten ideas of leadership and authority among those who had always looked to others for guidance and command. For these reasons the present efforts of Negroes in working together along various lines are peculiarly promising for the future of both races.