41. Pauperism—Emancipation and pauperism must ever go hand in hand; when a group of persons have been for generations prohibited from self-support, and self-initiative in any line, there is bound to be a large number of them who, when thrown upon their own resources, will be found incapable of competing in the race of life. Pennsylvania from early times, when emancipation of slaves in considerable numbers first began, has seen and feared this problem of Negro poverty. The Act of 1726 declared: “Whereas free Negroes are an idle and slothful people and often prove burdensome to the neighborhood and afford ill examples to other Negroes, therefore be it enacted * * * * that if any master or mistress shall discharge or set free any Negro, he or she shall enter into recognizance with sufficient securities in the sum of £30 to indemnify the county for any charge or incumbrance they may bring upon the same, in case such Negro through sickness or otherwise be rendered incapable of self-support.”

The Acts of 1780 and 1788 took pains to provide for Negro paupers in the county where they had legal residence, and many decisions of the courts bear upon this point. About 1820 when the final results of the Act of 1780 were being felt, an act was passed “To prevent the increase of pauperism in the Commonwealth;” it provided that if a servant was brought into the state over twenty-eight years of age (the age of emancipation) his master was to be liable for his support in case he became a pauper.1

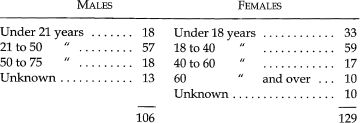

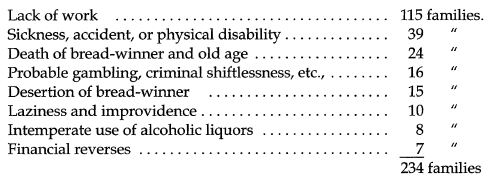

Thus we can infer that much pauperism was prevalent among the freedmen during these years although there are no actual figures on the subject. In 1837, 235 of the 1673 inmates of the Philadelphia County Almshouse were Negroes or 14 per cent of paupers from 7.4 per cent of the population. These paupers were classed as follows:2

Ten years later there were 196 Negro paupers in the Almshouse, and those receiving outdoor relief were reported as follows:3

In the City:

Of 2562 Negro families, 320 received assistance.

In Spring Garden:

Of 202 Negro families, 3 received assistance.

In Northern Liberties:

Of 272 Negro families, 6 received assistance.

In Southwark:

Of 287 Negro families, 7 received assistance.

In West Philadelphia:

Of 73 Negro families, 2 received assistance.

In Moyamensing:

Of 866 Negro families, 104 received assistance.

Total, of 4262 Negro families, 442 received assistance, or 10 per cent.

This practically covers the available statistics of the past; it shows a large amount of pauperism and yet perhaps not more than could reasonably be expected.

To-day it is very difficult to get any definite idea of the extent of Negro poverty; there is a vast amount of alms-giving in Philadelphia, but much of it is unsystematic and there is much duplication of work; and, at the same time, so meagre are the records kept that the real extent of pauperism and its causes are very hard to study.4

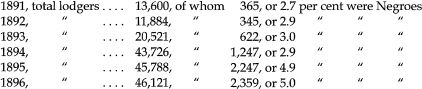

The first available figures are those relating to lodgers at the station houses—i. e., persons without shelter who have applied for and been given lodging:5

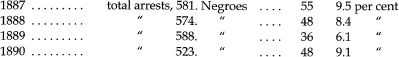

Somewhat similar statistics are furnished by the report of arrests by the vagrant detective for the last ten years:

The Negro vagrants arrested during the last six years were thus disposed of:

These records give a vague idea of that class of persons just hovering between pauperism and crime—tramps, loafers, defective persons and unfortunates—a class difficult to deal with because made up of diverse elements.

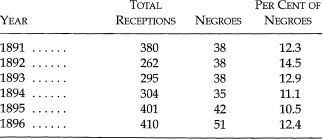

Turning to the true paupers, we have the record of the paupers admitted to the Blockley Almshouse during six years:

ADULTS–SIXTEEN YEARS OF AGE AND OVER

CHILDREN UNDER SIXTEEN YEARS OF AGE

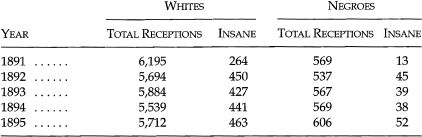

In 1891, 4.2 per cent of the whites admitted were insane and 2.3 per cent of the Negroes; in 1895, 8.3 per cent of the whites and 8.6 per cent of the Negroes:

We have already seen that in the Seventh Ward about 9 per cent of the Negroes can be classed as the “very poor,” needing public assistance in order to live. From this we may conclude that between three and four thousand Negro families in the city may be classed among the semi-pauper class. Thus it is plain that there is a large problem of poverty among the Negro problems; 4 per cent of the population furnish according to the foregoing statistics at least 8 per cent of the poverty. Considering the economic difficulties of the Negro, we ought perhaps to expect rather more than less than this. Beside these permanently pauperized families there is a considerable number of persons who from time to time must receive temporary aid, but can usually get on without it. In time of stress as during the year 1893 this class is very large.

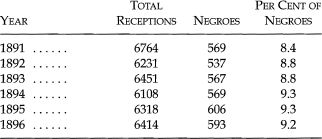

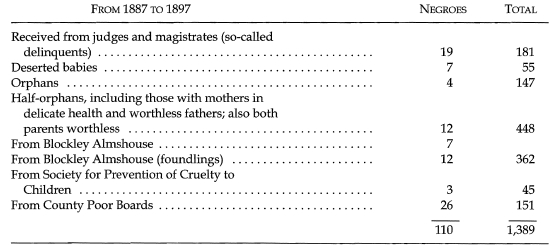

There is especial suffering and neglect among the children of this class of people: in the last ten years the Children’s Aid Society has received the following children:6

The total receptions during these ten years have been 1389, of which the Negroes formed 8 per cent. This but emphasizes the fact of poor family life among the lower classes which we have spoken of before.

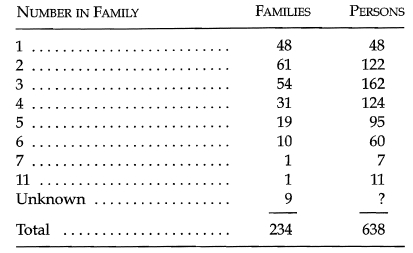

A little better light can be thrown on the problem of poverty by a study of concrete cases; for this purpose 237 families have been selected. They live in the Seventh Ward and are composed of those families of Negroes whom the Charity Organization Society, Seventh District, has aided for at least two winters.7 First, we must notice that this number nearly corresponds with the previously estimated per cent of the “very poor.” 8 Arranging these families according to size, we have:

The reported causes of poverty, which were in all cases verified by visitors so far as possible, were as follows:

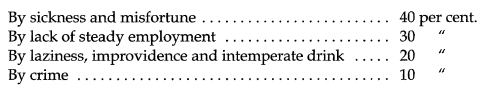

From as careful a consideration of these cases as the necessarily meagre information of records and visitors permit, it seems fair to say that Negro poverty in the Seventh Ward was, in these cases, caused as follows:

Of course this is but a rough estimate; many of these causes indirectly influence each other: crime causes sickness and misfortune; lack of employment causes crime; laziness causes lack of work, etc.

Several typical families will illustrate the varying conditions encountered:

No. 1.—South Eighteenth street. Four in the family; husband intemperate drinker; wife decent, but out of work.

No. 2.—South Tenth street. Five in the family; widow and children out of work, and had sold the bed to pay for expense of a sick child.

No. 3.—Dean street. A woman paralyzed; partially supported by a colored church.

No. 4.—Carver street. Worthy woman deserted by her husband five years ago; helped with coal, but is paying the Charity Organization Society back again.

No. 5.—Hampton street. Three in family; living in three rooms with three other families. “No push, and improvident.”

No. 6.—Stockton street. The woman has just had an operation performed in the hospital, and cannot work yet.

No. 7.—Addison street. Three in family; left their work in Virginia through the misrepresentations of an Arch street employment bureau; out of work.

No. 8.—Richard street. Laborer injured by falling of a derrick; five in the family. His fellow workmen have contributed to his support, but the employers have given nothing.

No. 9.—Lombard street. Five in family; wife white; living in one room; hard cases; rum and lies; pretended one child was dead in order to get aid.

No. 10.—Carver street. Woman and demented son; she was found very drunk on the street; plays policy.

No. 11.—Lombard street. Worthy woman sick with a tumor; given temporary aid.

No. 12.—Ohio street. Woman and two children deserted by her husband; helped to pay her rent.

No. 13.—Rodman street. A widow and child; out of work. “One very little room, clean and orderly.”

No. 14.—Fothergill street. Two in the family; the man sick, half-crazy and lazy; “going to convert Africa and didn’t want to cook;” given temporary help.

No. 15.—Lombard street. An improvident young couple out of work; living in one untidy room, with nothing to pay rent.

No. 16.—Lombard street. A poor widow of a wealthy caterer; cheated out of her property; has since died.

No. 17.—Ivy street. A family of four; husband was a stevedore, but is sick with asthma, and wife out of work; decent, but improvident.

No. 18.—Naudain street. Family of three; the man, who is decent, has broken his leg; the wife plays policy.

No. 19.—South Juniper street. Woman and two children; deserted by her husband, and in the last stages of consumption.

No. 20.—Radcliffe street. Family of three; borrowed of Charity Organization Society $1.00 to pay rent, and repaid it in three weeks.

No. 21.—Lombard street. “A genteel American white woman married to a colored man; he is at present in the South looking for employment; have one child;” both are respectable.

No. 22.—Fothergill street. Wife deserted him and two children, and ran off with a man; he is out of work; asked aid to send his children to friends.

No. 23.—Carver street. Man of twenty-three came from Virginia for work; was run over by cars at Forty-fifth street and Baltimore avenue, and lost both legs and right arm; is dependent on colored friends and wants something to do.

No. 24.—Helmuth street. Family of three; man out of work all winter, and wife with two and one-half days’ work a week; respectable.

No. 25.—Richard street. Widow, niece and baby; the niece betrayed and deserted. They ask for work.

42. The Drink Habit—The intemperate use of intoxicating liquors is not one of the Negro’s special offences; nevertheless there is considerable drinking and the use of beer is on the increase. The Philadelphia liquor saloons are conducted under an unusually well-administered system, and are not to so great an extent centres of brawling and loafing as in other cities; no amusements, as pool and billiards, are allowed in rooms where liquor is sold. This is not an unmixed good for the result is that much of the drinking is thus driven into homes, clubs and “speakeasies.” The increase of beer-drinking among all classes, black and white, is noticeable; the beer wagons deliver large numbers of bottles at private residences, and much is carried from the saloons in buckets.

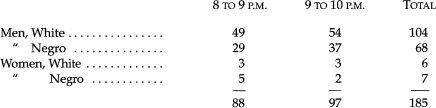

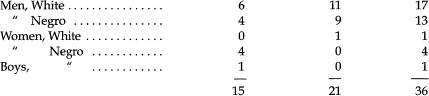

An attempt was made in 1897 to count the frequenters of certain saloons in the Seventh Ward during the hours from 8 to 10 on a Saturday night. It was impracticable to make this count simultaneously or to cover the whole ward, but eight or ten were watched each night.9 The results are a rough measurement of the drinking habits in this ward.

There are in the ward 52 saloons of which 26 were watched in districts mostly inhabited by Negroes. In these two hours the following record was made:

Persons entering the saloons:

Negroes—male, 1,373; female, 213. Whites—male, 1,445; female, 139.

Of those entering, the following are known to have carried liquor away:

Negroes—male, 238; female, 125. Whites—male, 275; female, 81.

3,170 persons entered half the saloons of the Seventh Ward in the hours from 8 to 10 of one Saturday night in December, 1897; of these, 1,586 were Negroes, and 1,584 were whites; 2,818 were males, and 352 were females.10 Of those entering these saloons at this time a part carried away liquor—mostly beer in tin buckets; of those thus visibly carrying away liquor there were in all 719; of these 363 were Negroes, and 356 were whites; 513 were males, and 206 were females.

The observers stationed near these saloons saw, in the two hours they were there, 79 drunken persons.

The general character of the saloons and their frequenters can best be learned from a few typical reports. The numbers given are the official license numbers:

No. 516. Persons entering saloon:

Men—white, 40; Negro, 68. Women—white, 12; Negro, 12.

Persons carrying liquor away:

Men—white, 8; Negro, 16. Women—white, 1; Negro, 3 Drunken persons seen, 12.

General character of saloon and frequenters:—“A small corner saloon, kept by a white man. The saloon appears to be a respectable one and has three entrances: one on Thirteenth street and the two on a small court. The majority of the colored patrons are poor people and of the working class. The white patrons are, for the greater part, of the better class. Among the latter very few were intoxicated.”

No. 488. Persons entering:

Men—white, 24; Negro, 102. Women—white, 2; Negro, 3.

Carrying liquor away, 12; drunken persons seen, 8.

General character:—“The saloon was none too orderly; policemen remained near all the time; the Negro men entering were as a rule well dressed—perhaps one-third were laborers; the white men were well dressed but suspicious looking characters.”

No. 515. Persons entering:

Men—white, 81; Negro, 59. Women—white, 4; Negro, 10.

Persons carrying liquor away:

Men—white, 15 (one a boy of 12 or 14 years of age); Negro, 11. Women—white, 4; Negro, 8.

Drunken persons seen, 2 (to one nothing was sold).

General character of saloon and frequenters:—“There were two Negro men and seven white men in saloon when the count was started. The place has three doors but all are easily observed. Trade is largely in distilled liquors, and a great deal is sold in bottles—a ‘barrel shop.’ ”

No. 527. Persons entering saloon:

Persons carrying liquor away:

Drunken persons seen, none.

General character of saloon and frequenters:—“Quiet, orderly crowd—quick trade—no loafing. Three boys were among those entering.”

No. 484. Persons entering saloon:

Men—white, 70; Negro, 32. Women—white, 10; Negro, 1.

Persons carrying liquor away:

Men—white, 10; Negro, 12. Women—white, 4; Negro, 0.

Drunken persons seen, 11, six of whom were white and five black. “I cannot say that the saloon was responsible for all of them, but they were all in or about it.”

This saloon is in the worst slum section of the ward and is of bad character. Frequenters were a mixed lot, “fast, tough, criminal and besotted.”

Men—white, 79; Negro, 129. Women—white, 13; Negro, 34.

Persons carrying liquor away:

Men—white, 15; Negro, 25. Women—white, 5; Negro, 8.

“No drunken men seen. Frequented by a sharp class of criminals and loafers. Near the notorious ‘Middle Alley.’ ”

No. 525.

Total Negroes entering, 14; total whites entering, 13.

“No loafers about the front of the saloon. Streets well lighted and neighborhood quiet, according to the policeman. There was a barber shop next door and a saloon on the corner ten doors below. Very few drunken people were seen. Trade was most brisk between eight and nine o’clock. In two hours one more Negro than white entered. Two more Negroes, men, than whites carried away liquor. One white man, a German, returned three times for beer in a kettle. Two Negro women carried beer away in kettles; one white woman (Irish) made two trips. All women entered by side door. The saloon is under a residence, three stories, corner of Waverly and Eleventh streets. Waverly street has a Negro population which fairly swarms—good position for Negro trade. Proprietor and assistant were both Irish. The interior of the saloon was finished in white pine stained to imitate cherry. Extremely plain. Barkeeper said, ‘A warm night, but we are doing very well.’ One beggar came in, a colored‘Auntie’ she wanted bread, not gin. Negroes were well dressed, as a rule, many smoking. The majority of frequenters by their bustling air and directness with which they found the place, showed long acquaintance with the neighborhood; especially this corner.”

No. 500. Persons entering saloon:

Men—white, 40; Negro, 73. Women—white 4; Negro, 6.

Persons carrying liquor away:

Men—white, 6; Negro, 23. Women—white, 5; Negro, 4.

Drunken persons seen, 1.

General character of saloon and frequenters:—“Four story building, plain and neat; three entrances; iron awning; electric and Welsbach lights. Negroes generally tidy and appear to be pretty well-to-do. Whites not so tidy as Negroes and generally mechanics. Almost all smoke cigars. Liquor carried away openly in pitchers and kettles. Three of the white women, carrying away liquor, looked like Irish servant girls. Some of the Negroes carried bundles of laundry and groceries with them.”

Few general conclusions can be drawn from this data. The saloon is evidently not so much a moral as an economic problem among Negroes; if the 1,586 Negroes who went into the saloons within two hours Saturday night spent five cents apiece, which is a low estimate, they spent $79.30. If, as is probable, at least $100 was spent that Saturday evening throughout the ward, then in a year we would not be wrong in concluding their Saturday night’s expenditure was at least $5,000, and their total expenditure could scarcely be less than $10,000, and it may reach $20,000—a large sum for a poor people to spend in liquor.

43. The Causes of Crime and Poverty—A study of statistics seems to show that the crime and pauperism of the Negroes exceeds that of the whites; that in the main, nevertheless, it follows in its rise and fall the fluctuations shown in the records of the whites, i. e., if crime increases among the whites it increases among Negroes, and vice versa, with this peculiarity, that among the Negroes the change is always exaggerated—the increase greater, the decrease more marked in nearly all cases. This is what we would naturally expect: we have here the record of a low social class, and as the condition of a lower class is by its very definition worse than that of a higher, so the situation of the Negroes is worse as respects crime and poverty than that of the mass of whites. Moreover, any change in social conditions is bound to affect the poor and unfortunate more than the rich and prosperous. We have in all probability an example of this in the increase of crime since 1890; we have had a period of financial stress and industrial depression; the ones who have felt this most are the poor, the unskilled laborers, the inefficient and unfortunate, and those with small social and economic advantages: the Negroes are in this class, and the result has been an increase in Negro crime and pauperism; there has also been an increase in the crime of the whites, though less rapid by reason of their richer and more fortunate upper classes.

So far, then, we have no phenomena which are new or exceptional, or which present more than the ordinary social problems of crime and poverty—although these, to be sure, are difficult enough. Beyond these, however, there are problems which can rightly be called Negro problems: they arise from the peculiar history and condition of the American Negro. The first peculiarity is, of course, the slavery and emancipation of the Negroes. That their emancipation has raised them economically and morally is proven by the increase of wealth and co-operation, and the decrease of poverty and crime between the period before the war and the period since; nevertheless, this was manifestly no simple process: the first effect of emancipation was that of any sudden social revolution: a strain upon the strength and resources of the Negro, moral, economic and physical, which drove many to the wall. For this reason the rise of the Negro in this city is a series of rushes and backslidings rather than a continuous growth. The second great peculiarity of the situation of the Negroes is the fact of immigration; the great numbers of raw recruits who have from time to time precipitated themselves upon the Negroes of the city and shared their small industrial opportunities, have made reputations which, whether good or bad, all their race must share; and finally whether they failed or succeeded in the strong competition, they themselves must soon prepare to face a new immigration.

Here then we have two great causes for the present condition of the Negro: Slavery and emancipation with their attendant phenomena of ignorance, lack of discipline, and moral weakness; immigration with its increased competition and moral influence. To this must be added a third as great—possibly greater in influence than the other two, namely the environment in which a Negro finds himself—the world of custom and thought in which he must live and work, the physical surrounding of house and home and ward, the moral encouragements and discouragements which he encounters. We dimly seek to define this social environment partially when we talk of color prejudice—but this is but a vague characterization; what we want to study is not a vague thought or feeling but its concrete manifestations. We know pretty well what the surroundings are of a young white lad, or a foreign immigrant who comes to this great city to join in its organic life. We know what influences and limitations surround him, to what he may attain, what his companionships are, what his encouragements are, what his drawbacks.

This we must know in regard to the Negro if we would study his social condition. His strange social environment must have immense effect on his thought and life, his work and crime, his wealth and pauperism. That this environment differs and differs broadly from the environment of his fellows, we all know, but we do not know just how it differs. The real foundation of the difference is the widespread feeling all over the land, in Philadelphia as well as in Boston and New Orleans, that the Negro is something less than an American and ought not to be much more than what he is. Argue as we may for or against this idea, we must as students recognize its presence and its vast effects.

At the Eastern Penitentiary where they seek so far as possible to attribute to definite causes the criminal record of each prisoner, the vast influence of environment is shown. This estimate is naturally liable to error, but the peculiar system of this institution and the long service and wide experience of the warden and his subordinates gives it a peculiar and unusual value. Of the 541 Negro prisoners previously studied 191 were catalogued as criminals by reason of “natural and inherent depravity.” The others were divided as follows:

This rough judgment of men who have come into daily contact with five hundred Negro criminals but emphasizes the fact alluded to; the immense influence of his peculiar environment on the black Philadelphian; the influence of homes badly situated and badly managed, with parents untrained for their responsibilities; the influence of social surroundings which by poor laws and inefficient administration leave the bad to be made worse; the influence of economic exclusion which admits Negroes only to those parts of the economic world where it is hardest to retain ambition and self-respect; and finally that indefinable but real and mighty moral influence that causes men to have a real sense of manhood or leads them to lose aspiration and self-respect.

For the last ten or fifteen years young Negroes have been pouring into this city at the rate of a thousand a year; the question is then what homes they find or make, what neighbors they have, how they amuse themselves, and what work they engage in? Again, into what sort of homes are the hundreds of Negro babies of each year born? Under what social influences do they come, what is the tendency of their training, and what places in life can they fill? To answer all these questions is to go far toward finding the real causes of crime and pauperism among this race; the next two chapters, therefore, take up the question of environment.