25. The Interpretation of Statistics—The characteristic signs which usually accompany a low civilization are a high birth rate and a high death rate; or, in other words, early marriages and neglect of the laws of physical health. This fact, which has often been illustrated by statistical research, has not yet been fully apprehended by the general public because they have long been used to hearing more or less true tales of the remarkable health and longevity of barbarous peoples. For this reason the recent statistical research which reveals the large death rate among American Negroes is open to very general misapprehension. It is a remarkable phenomenon which throws much light on the Negro problems and suggests some obvious solutions. On the other hand, it does not prove, as most seem to think, a vast recent change in the condition of the Negro. Reliable data as to the physical health of the Negro in slavery are entirely wanting; and yet, judging from the horrors of the middle passage, the decimation on the West Indian plantations, and the bad sanitary condition of the Negro quarters on most Southern plantations, there must have been an immense death rate among slaves, notwithstanding all reports as to endurance, physical strength and phenomenal longevity. Just how emancipation has affected this death rate is not clear; the rush to cities, where the surroundings are unhealthful, has had a bad effect, although this migration on a large scale is so recent that its full effect is not yet apparent; on the other hand, the better care of children and improvement in home life has also had some favorable effect. On the whole, then, we must remember that reliable statistics as to Negro health are but recent in date and that as yet no important conclusions can be arrived at as to historic changes or tendencies. One thing we must of course expect to find, and that is a much higher death rate at present among Negroes than among whites: this is one measure of the difference in their social advancement. They have in the past lived under vastly different conditions and they still live under different conditions: to assume that, in discussing the inhabitants of Philadelphia, one is discussing people living under the same conditions of life, is to assume what is not true. Broadly speaking, the Negroes as a class dwell in the most unhealthful parts of the city and in the worst houses in those parts; which is of course simply saying that the part of the population having a large degree of poverty, ignorance and general social degradation is usually to be found in the worst portions of our great cities.

Therefore, in considering the health statistics of the Negroes, we seek first to know their absolute condition, rather than their relative status; we want to know what their death rate is, how it has varied and is varying and what its tendencies seem to be; with these facts fixed we must then ask, What is the meaning of a death rate like that of the Negroes of Philadelphia? Is it, compared with other races, large, moderate or small; and in the case of nations or groups with similar death rates, What has been the tendency and outcome? Finally, we must compare the death rate of the Negroes with that of the communities in which they live and thus roughly measure the social difference between these neighboring groups; we must endeavor also to eliminate, so far as possible, from the problem disturbing elements which would make a difference in health among people of the same social advancement. Only in this way can we intelligently interpret statistics of Negro health.

Here, too, we have to remember that the collection of statistics, even in Philadelphia, is by no means perfect. The death returns are to be relied upon, but the returns of births are wide of the true condition; the statistics of causes of death are also faulty.

26. The Statistics of the City—The mortality of Negroes in Philadelphia, according to the best reports, has been as follows:1

| DATE | AVERAGE ANNUAL DEATHS PER 1000 NEGROES |

| 1820–1830 | 47.6 |

| 1830–1840 | 32.5 |

| 1884–1890 | 31.25* |

| 1891–1896 | 28.02† |

*Including still-births; excluding still-births, 29.52.

†Including still-births and assuming the average Negro population, 1891–1896, at the low figure of 41,500.2 For this period, excluding still-births, 25.41.

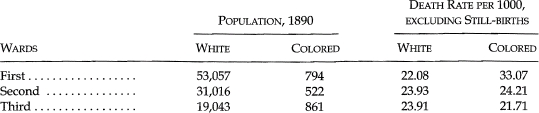

The average annual death rate, 1884 to 1890, in the wards having over 1,000 Negro inhabitants, was as follows:

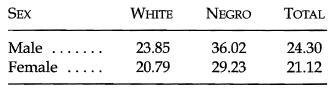

Separating the deaths by the sex of the deceased, we have:

| Total death rate of Negroes, 1890, (still-births included) | 32.42 per 1000 |

| For Negro males | 36.02 ” |

| For Negro females | 29.23 ” |

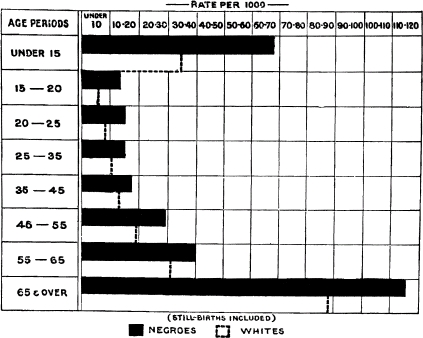

Separating by age, we have:

| Total death rate, 1890 (still-births included) all ages | 32.42 per 1000 |

| Under fifteen | 69.24 ” |

| Fifteen to twenty | 13.61 ” |

| Twenty to twenty-five | 14.50 ” |

| Twenty-five to thirty-five | 15.21 ” |

| Thirty-five to forty-five | 17.16 ” |

| Forty-five to fifty-five | 29.41 ” |

| Fifty-five to sixty-five | 40.09 ” |

| Sixty-five and over | 116.49 ” |

The large infant mortality is shown by the average annual rate of 171.44 (including still-births), for children under five years of age, during the years 1884 to 1890.

These statistics are very instructive. Compared with modern nations the death rate of Philadelphia Negroes is high, but not extraordinarily so: Hungary (33.7), Austria (30.6), and Italy (28.6), had in the years 1871–90 a larger average than the Negroes in 1891–96, and some of these lands surpass the rate of 1884–90. Many things combine to cause the high Negro death rate: poor heredity, neglect of infants, bad dwellings and poor food. On the other hand the age classification of city Negroes with its excess of females and of young people of twenty to thirty-five years of age, must serve to keep the death rate lower than its rate would be under normal circumstances. The influence of bad sanitary surroundings is strikingly illustrated in the enormous death rate of the Fifth Ward—the worst Negro slum in the city, and the worst part of the city in respect to sanitation. On the other hand the low death rate of the Thirtieth Ward illustrates the influences of good houses and clean streets in a district where the better class of Negroes have recently migrated.

The marked excess of the male death rate points to a great difference in the social condition of the sexes in the city, as it far exceeds the ordinary disparity; as, e. g., in Germany where the rates are, males 28.6, females 25.3.3 The young girls who come to the city have practically no chance for work except domestic service. This branch of work, however, has the great advantage of being healthful; the servant has usually a good dwelling, good food and proper clothing. The boy, on the contrary, usually has to live in a bad part of the city, on poorly prepared or irregular food and is more exposed to the weather. Moreover, his chances of securing any work at all are much smaller than the girls’. Consequently the female death rate is but 81 per cent of the male rate.

When we turn to the statistics of death according to age, we immediately see that, as is usual in such cases, the high death rate is caused by an excessive infant mortality, which ranks very high compared with other groups.

The chief diseases to which Negroes fall victims are:4

| DISEASE | DEATH RATE PER 100,000, 1890 |

| Consumption | 532.52 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 388.86 |

| Pneumonia | 356.67 |

| Heart disease and dropsy | 257.59 |

| Still-births | 203.10 |

| Diarrheal diseases | 193.19 |

| Diseases of the urinary organs | 133.75 |

| Accidents and injuries | 99.07 |

| Typhoid fever | 91.64 |

For the period, 1891–1896, the average annual rate was as follows:

| DISEASE | DEATH RATE PER 100,000, 1891–1896 |

| Consumption | 426.50 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 307.63 |

| Pneumonia | 290.76 |

| Heart disease and dropsy | 172.69 |

| Still and premature births | 210.12 |

| Typhoid fever | 44.98 |

The strikingly excessive rate here is that of consumption, which is the most fatal disease for Negroes. Bad ventilation, lack of outdoor life for women and children, poor protection against dampness and cold are undoubtedly the chief causes of this excessive death rate. To this must be added some hereditary predisposition, the influence of climate, and the lack of nearly all measures to prevent the spread of the disease.

We find thus a group of people with a high, but not unusual, death rate, which rate has been gradually decreasing, if statistics are reliable, for seventy-five years. This death rate is due principally to infantile mortality and consumption, and these are caused chiefly by conditions of life and poor hereditary physique.

How now does this group compare with the condition of the mass of the community with which it comes in daily contact? Comparing the death rates of whites and Negroes, we have:

| DATE | WHITES | NEGROES |

| 1820–1830 | 47.6 | |

| 1830–1840 | 23.7 | 32.5 |

| 1884–1890* | 22.69 | 31.25 |

| 1891–1896† | 21.20‡ | 25.41§ |

*Including still-births.

†Excluding still-births.

‡Assuming white population, 1891–96, has increased in the same ratio as 1880–90, and that it averaged 1,066,985 in these years.

§Assuming that the mean Negro population was 41,500.

This shows a considerable difference in death rates, amounting to nearly 10 per cent in 1884–1890, and to 4 per cent by the estimated rates of 1891–1896. If the estimate of population on which the latter rate is based is correct, then the difference in death rate is not larger than would be expected from different conditions of life.5

The absolute number of deaths (excluding still-births) has been as follows:

| YEAR | WHITES | NEGROES |

| 1891 | 22,384 | 983 |

| 1892 | 23,233 | 1,072 |

| 1893 | 22,621 | 1,034 |

| 1894 | 21,960 | 1,030 |

| 1895 | 22,645 | 1,151 |

| 1896 | 22,903 | 1,079 |

Comparing the death rate by wards we have this table:

POPULATION AND DEATH RATE, PHILADELPHIA, 1884–90

*Death rate included in that of the Twenty-fourth ward

From this table we may make some interesting comparisons; take first the worst wards:

| WARD | WHITES | NEGROES* |

| Fourth | 29.98 | 43.38 |

| Fifth | 25.67 | 48.46 |

| Seventh | 24.30 | 30.54 |

| Eighth | 24.26 | 29.25 |

*Total Negro population, 16,780.

In all these wards there is a large Negro population comprising a considerable per cent of new immigrants; and these wards contain the worst slum districts and most unsanitary dwellings “of the city”. However, there are in these same wards peculiar circumstances which decrease the death rate of the whites: First, in the Fourth and Fifth wards a large number of foreign immigrants whose death rate, on account of the absence of old people and children, is small; and of Jews whose death rate is, on account of their fine family life, also small; secondly, in the Seventh and Eighth wards there are, as all Philadelphians know, large sections inhabited by the best people of the city, with a death rate below the average.

Taking another set of wards, we have:

| WARD | WHITES | NEGROES* |

| Fourteenth | 21.47 | 22.38 |

| Fifteenth | 20.08 | 20.18 |

| Twenty-sixth | 19.48 | 18.15 |

| Twenty-seventh | 31.91 | 39.86 |

| Thirtieth | 22.12 | 21.74 |

*Total Negro population, 8,371.

Here we have quite a different tale. These are the wards where the best Negro families have been renting and buying homes in the last ten years, in order to escape from the crowded downtown wards. The Thirtieth and Twenty-sixth wards are the best sections; the statistics of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth wards show the same thing although their validity is somewhat vitiated by the large number of Negro servants there in the prime of life.

A last set of wards is as follows:

| WARD | WHITES | NEGROES* |

| Twentieth | 20.77 | 18.64 |

| Twenty-second | 17.77 | 15.91 |

| Twenty-third | 18.50 | 18.67 |

| Twenty-eighth | 15.56 | 15.96 |

| Twenty-ninth | 20.19 | 19.09 |

*Total Negro population, 6,277.

In most of these some exceptional circumstances make the Negro death rate abnormally low. Generally this arises from the fact that these are white residential wards and the Negro population is largely composed of servants. These, as has been before noted, have a small death rate because of their ages, and then too, when they are sick they go home to die in the Seventh Ward, or to the hospitals in the Twenty-seventh and other wards.

These tables would seem to adduce considerable proof that the Negro death rate is largely a matter of condition of living.

When we look at the comparative deaths of the races, by sex, we see that the forces operating among Negroes to make a disparity between the death rates of men and women are largely absent among the whites.

(1890, including still-births.)

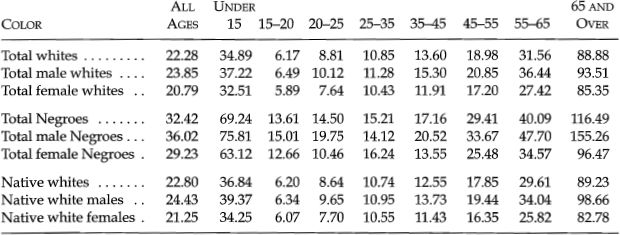

The age structure reveals partially the character of the great differences in death rate between the races. (See page 112.)

DEATH RATE OF PHILADELPHIA BY AGE PERIODS, FOR 1890.

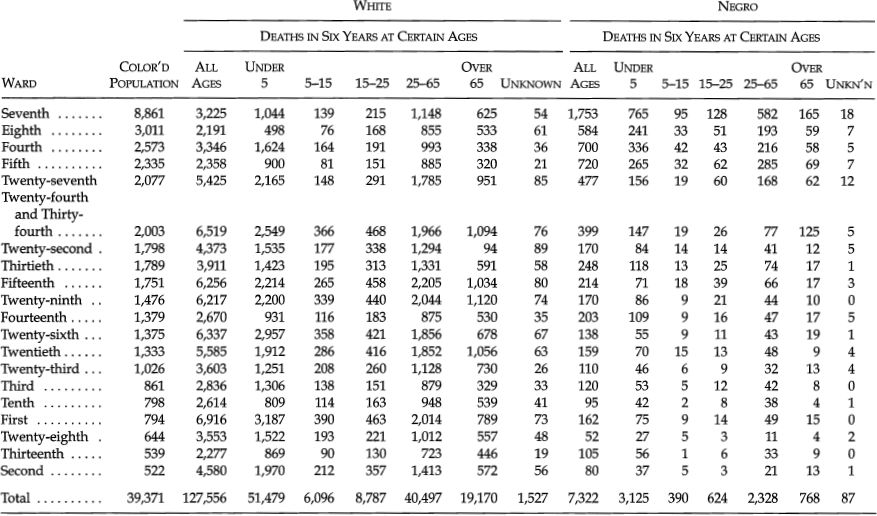

NUMBER OF DEATHS IN PHILADELPHIA, BY AGES, 1884–1890

DEATH RATE IN PHILADELPHIA, 1890, BY EIGHT AGE PERIODS

For children under five, including still-births, we find these average annual death rates, 1884–1890:

| RACE | CITY | SEVENTH WARD |

| Native white | 94.00 | 111.04 |

| Negro | 171.44 | 188.82 |

| Total population | 94.79 | 132.63 |

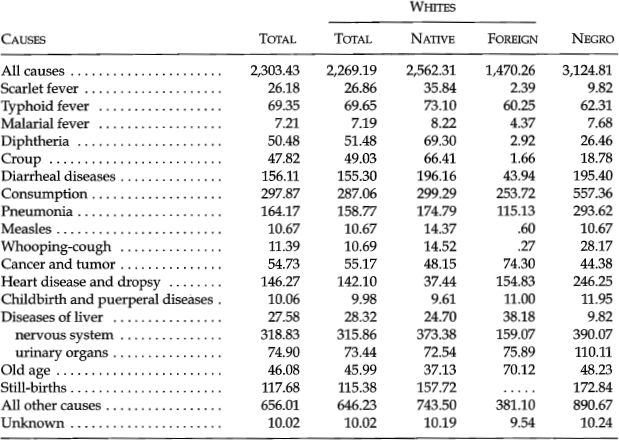

Nothing shows more plainly the poor home life of the Negroes than these figures. A comparison of the differences in death rate from various diseases will complete the picture:

DEATH RATE PER 100,000 FROM SPECIFIED DISEASES, 1890

For Whole City

| DISEASE | NEGRO | WHITE |

| Consumption | 532.52 | 269.42 |

| Pneumonia | 356.67 | 180.31 |

| Diarrheal diseases | 193.19 | 151.40 |

| Diseases of the nervous system | 388.86 | 302.01 |

| Diphtheria and croup | 44.58 | 82.06 |

| Diseases of the urinary system | 133.75 | 60.81 |

| Heart disease and dropsy | 257.59 | 157.16 |

| Cancer and tumor | 37.15 | 56.63 |

| Disease of the liver | 12.38 | 27.82 |

| Malarial fever | 7.43 | 5.66 |

| Typhoid fever | 91.64 | 72.82 |

| Still-births | 203.10 | 135.61 |

| Suicides | 3.20 | 12.99 |

| Other accidents and injuries | 99.07 | 78.78 |

AVERAGE ANNUAL DEATH RATE OF PHILADELPHIA, 1884–1890, PER EACH 100,000 OF POPULATION

For Specified Diseases

The Negroes exceed the white death rate largely in consumption, pneumonia, diseases of the urinary system, heart disease and dropsy, and in still-births; they exceed moderately in diarrheal diseases, diseases of the nervous system, malarial and typhoid fevers. The white death rate exceeds that of Negroes for diphtheria and croup, cancer and tumor, diseases of the liver, and deaths from suicide.

We have side by side and in intimate relationship in a large city two groups of people, who as a mass differ considerably from each other in physical health; the difference is not so great as to preclude hopes of final adjustment; probably certain social classes of the larger group are in no better health than the mass of the smaller group. So too there are without doubt classes in the smaller group whose physical condition is equal to, or superior to the average of the larger group. Particularly with regard to consumption it must be remembered that Negroes are not the first people who have been claimed as its peculiar victims; the Irish were once thought to be doomed by that disease—but that was when Irishmen were unpopular.

Nevertheless, so long as any considerable part of the population of an organized community is, in its mode of life and physical efficiency distinctly and noticeably below the average, the community must suffer. The suffering part furnishes less than its quota of workers, more than its quota of the helpless and dependent and consequently becomes to an extent a burden on the community. This is the situation of the Negroes of Philadelphia to-day: because of their physical health they receive a larger portion of charity, spend a larger proportion of their earnings for physicians and medicine, throw on the community a larger number of helpless widows and orphans than either they or the city can afford. Why is this? Primarily it is because the Negroes are as a mass ignorant of the laws of health. One has but to visit a Seventh Ward church on Sunday night and see an audience of 1500 sit two and three hours in the foul atmosphere of a closely shut auditorium to realize that long formed habits of life explain much of Negro consumption and pneumonia; again the Negroes live in unsanitary dwellings, partly by their own fault, partly on account of the difficulty of securing decent houses by reason of race prejudice. If one goes through the streets of the Seventh Ward and picks out those streets and houses which, on account of their poor condition, lack of repair, absence of conveniences and limited share of air and light, contain the worst dwellings, one finds that the great majority of such streets and houses are occupied by Negroes. In some cases it is the Negroes’ fault that the houses are so bad; but in very many cases landlords refuse to repair and refit for Negro tenants because they know that there are few dwellings which Negroes can hire, and they will not therefore be apt to leave a fair house on account of damp walls or poor sewer connections. Of modern conveniences Negro dwellings have few. Of the 2441 families of the Seventh Ward only 14 per cent had water closets and baths, and many of these were in poor condition. In a city of yards, 20 per cent of the families had no private yard and consequently no private outhouses.

Again, in habits of personal cleanliness and taking proper food and exercise, the colored people are woefully deficient. The Southern field-hand was hardly supposed to wash himself regularly, and the house servants were none too clean. Habits thus learned have lingered, and a gospel of soap and water needs now to be preached. Negroes are commonly supposed to eat rather more than necessary. And this perhaps is partially true. The trouble is more in the quality of the food than its quantity, in the wasteful method of its preparation, and in the irregularity in eating.6 For instance, one family of three living in the depth of dirt and poverty on a crime-stricken street spent for their daily food:

| CENTS | |

| Milk, for child | 4 |

| One pound pork chops | 10 |

| One loaf bread | 5 |

| 19 |

When we imagine this pork fried in grease and eaten with baker’s bread, taken late in the afternoon or at bedtime, what can we expect of such a family? Moreover, the tendency of the classes who are just struggling out of extreme poverty is to stint themselves for food in order to have better looking homes; thus the rent in too many cases eats up physical nourishment.

Finally, the number of Negroes who go with insufficient clothing is large. One of the commonest causes of consumption and respiratory disease is migration from the warmer South to a Northern city without change in manner of dress. The neglect to change clothing after becoming damp with rain is a custom dating back to slavery time.

These are a few obvious matters of habit and manner of life which account for much of the poor health of Negroes. Further than this, when in poor health the neglect to take proper medical advice, or to follow it when given, leads to much harm. Often at the hospital a case is treated and temporary relief given, the patient being directed to return after a stated time. More often with Negroes than with whites, the patient does not return until he is worse off than at first. To this must be added a superstitious fear of hospitals prevalent among the lower classes of all people, but especially among Negroes. This must have some foundation in the roughness or brusqueness of manner prevalent in many hospitals, and the lack of a tender spirit of sympathy with the unfortunate patients. At any rate, many a Negro would almost rather die than trust himself to a hospital.

We must remember that all these bad habits and surroundings are not simply matters of the present generation, but that many generations of unhealthy bodies have bequeathed to the present generation impaired vitality and hereditary tendency to disease. This at first seems to be contradicted by the reputed robustness of older generations of blacks, which was certainly true to a degree. There cannot, however, be much doubt, when former social conditions are studied, but that hereditary disease plays a large part in the low vitality of Negroes to-day, and the health of the past has to some extent been exaggerated. All these considerations should lead to concerted efforts to root out disease. The city itself has much to do in this respect. For so large and progressive a city its general system of drainage is very bad; its water is wretched, and in many other respects the city and the whole State are “woefully and discreditably behind almost all the other States in Christendom.”7 The main movement for reform must come from the Negroes themselves, and should start with a crusade for fresh air, cleanliness, healthfully located homes and proper food. All this might not settle the question of Negro health, but it would be a long step toward it.

The most difficult social problem in the matter of Negro health is the peculiar attitude of the nation toward the well-being of the race. There have, for instance, been few other cases in the history of civilized peoples where human suffering has been viewed with such peculiar indifference. Nearly the whole nation seemed delighted with the discredited census of 1870 because it was thought to show that the Negroes were dying off rapidly, and the country would soon be well rid of them. So, recently, when attention has been called to the high death rate of this race, there is a disposition among many to conclude that the rate is abnormal and unprecedented, and that, since the race is doomed to early extinction, there is little left to do but to moralize on inferior species.

Now the fact is, as every student of statistics knows, that considering the present advancement of the masses of the Negroes, the death rate is not higher than one would expect; moreover there is not a civilized nation to-day which has not in the last two centuries presented a death rate which equaled or surpassed that of this race. That the Negro death rate at present is anything that threatens the extinction of the race is either the bugbear of the untrained, or the wish of the timid.

What the Negro death rate indicates is how far this race is behind the great vigorous, cultivated race about it. It should then act as a spur for increased effort and sound upbuilding, and not as an excuse for passive indifference, or increased discrimination.