Chapter 4. The Centralized Partnership

CORPORATE ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES ARE often employed without intentionality. People use what’s worked for them in the past, typically some form of hierarchical bureaucracy, broken up into functional departments. Design teams embed themselves in these structures, modeling themselves on the other functional departments.

These structures, though, are products of 19th- and 20th-century industrial thinking.[13] Design, which has emerged as a primary discipline because of 21st-century concerns of connected software and services, will be stymied if it simply conforms to these outdated practices. To realize design’s potential, design leaders must be thoughtful and intentional about how the design organization is structured and shaped.

Organizational Models for Design Teams

When the design team is small, say just five members, its organizational model is straightforward—it’s the design team. The team is focused on a couple of key projects, and doesn’t have to think too hard about how to tackle them—at that size, just do what feels right.

As the team grows, if something isn’t done about this structure, everyone will report to one boss, and there will be one undifferentiated mass of designers trying to work together. That is not sustainable. The design team must evolve into a design organization, with explicit consideration around structure, project work, and cross-functional collaboration. Historically, there have been two ways that design organizations have typically operated: either as centralized internal services, or decentralized and embedded. Each has benefits and drawbacks, which we’ll explore in some detail. We’ll then introduce a third way, what we call the Centralized Partnership. Though unorthodox, it potentially leads the way for thinking about how functional teams (not just design!) should be structured to tackle 21st-century challenges.

Centralized Internal Services

Given that most companies’ initial experience with design is by working with an external design agency, it’s not surprising that when they first started building in-house design teams, the common organizational model was a centralized internal services firm, operating essentially as an in-house agency.

In the agency model, the organization is led by a director (who may have a design background, or may just be a professional manager tasked with overseeing the operations of the design team) who oversees a series of teams organized by functions such as interaction design, information architecture, visual design, usability, and project management. Each team is led by a manager, whose qualification was that they were the most senior practitioner of that particular function. These in-house agencies are typically placed inside a marketing organization (if the website was seen primarily as a marketing vehicle), an IT organization (because the Web was delivered on computers), or a newly created “digital” or “ecommerce” team.

This internal services group is seen as a pool of talent upon which to draw as needed by projects. Someone from “the business” (a product group, or a line of business, or marketing), would reach out to the director with a request for design work. Often this takes the shape of a creative brief that makes clear what is needed and in what time frame.

After some back and forth between the director and business representative, a project plan is settled upon, and the director then works with an internal resourcing manager to figure out who is available from which functional teams, and assigns them to do the work. That team tackles the problem in the given time frame (as varied as two days to two months to two years), and when the project is finished, the designers return to the pool, waiting for their next assignment.

Many companies go so far as to literally treat their internal design team as if it were an external firm, where the business unit requesting design pays chargebacks to the internal team, and where the business may opt to work with a design agency if it found it a preferable relationship.

Benefits of centralization

This form of centralization is so out of favor, it can be hard to remember why anyone would operate this way. That said, it’s worth recognizing that it offers some very real benefits:

Supports an internal design community and culture

Provides clear lines of authority and control

Allows designers to work on a range of projects

Encourages a consistent user experience

Create efficiencies in doing the work

From the perspective of the design team, the strongest benefit of centralization is how it supports the development of a design community. An internal services team, operating as an in-house agency, can replicate the focus and commitment of a design firm. This encourages the emergence of a strong design culture, as designers spend much of their time interacting and learning from one another. Designers have a clear sense of how they can grow their skills, and their careers. They have managers who can serve as mentors.

That straightforwardness in the centralized design team structure also provides clear lines of authority and control. For design direction and approval, there are no questions, as vision setting and decision making resides with the senior-most members of the team. This helps the designers focus on their work, because they don’t need to worry about conflicting feedback. If there are issues or concerns, escalation paths are clear.

Also similar to an external firm, another benefit for designers is that they work on a wide range of projects, with different parts of the business, and of varying length and scale. This exposure broadens their understanding of how to apply design, and the variety keeps them engaged.

The clearest benefit for customers is that this approach encourages consistency across the company’s designed experiences. A centralized team establishes design guidelines, and enforces them through the projects they take on. A customer knows what to expect regardless of which part of the company he is engaging with.

For the design team, these guidelines also lead to efficiencies in their work product. Once you solve a design problem for one part of the business, if another part of the business poses a similar problem, it’s speedier to solve. The design team achieves quicker turnaround times on such repetitious challenges, and should be able to focus their effort on harder novel problems.

The finance department realizes the biggest benefit of centralization. By having all the designers on one team, there is no risk of redundant roles throughout the organization, keeping headcount costs down.

Related to that, if the centralized team uses chargebacks, it’s very clear that design is something you pay for, not just some assumed utility like phone calls or printer paper. If a part of the business wants design, they need a good justification, and that will make them more serious about it.

Drawbacks of centralization

While centralization makes a lot of abstract business sense, when it comes to day-to-day practice, it proves problematic for the following reasons:

Disempowerment and lack of ownership

“Us versus them” attitude

Lack of clarity around priority and timing

The gravest issue for designers is that they find themselves fundamentally disempowered. By the time designers are brought in to the project, the important decisions have already been made. Their concerns about assumptions underlying a brief are easily dismissed, because those designers will be gone when their part of the work is over. It’s the people in the business who are held accountable, and with that accountability comes authority.

Design may be seen only as aesthetics and styling, or as one former client referred to it, “SUAC: Shut Up and Color.” God forbid you actually conduct any usability studies, because any issues found will probably not get addressed, as designs need to be handed to the engineers at a specified time in order to meet the predetermined ship date.

This disempowerment leads to designers developing an “us versus them” attitude. They become disenchanted, nodding during meetings, but rolling their eyes afterward at the requirements they’ve been handed. They put in the bare minimum to get the work done, because their effort isn’t going to be appreciated. And such attitude and behavior only reinforces the business’s treatment of designers, leading to a vicious cycle of diminished expectations.

The business units requesting design get frustrated because they have no real control over this function. They have pressing and important needs, but they have to wait for the design organization to be able to staff a team. Other projects are given priority, and they don’t understand why. When they finally do get design resources, the deadlines are such that there’s not enough time for any creativity. They have to wait for internal design team reviews before work gets approved. And so the business feels that they had to wait a long time, only to get substandard work.

After this happens enough times, business units (or product teams) agitate for change. They want total control over what they produce.

Decentralized and Embedded

When a company realizes that its centralized, function-based organization is leading to delays, subpar work, and unsatisfying outcomes, a common solution is to reorganize into wholly staffed, independent teams, with all the capabilities necessary for delivery. This reduces overhead by giving these teams autonomy to make decisions that benefit themselves, with the expectation that if everyone is looking out for their best interests, that will bubble up and serve the interests of the company as a whole.

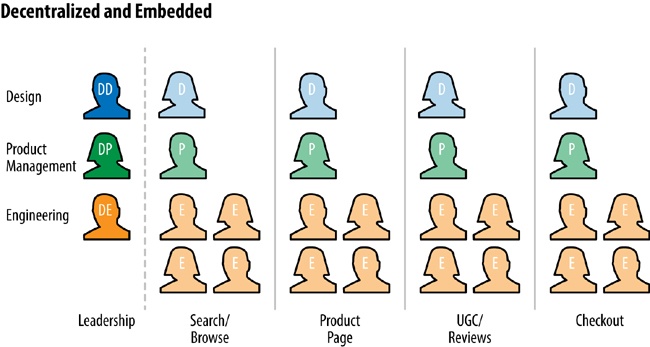

Design teams follow suit. Instead of a single design organization, designers embed within these decentralized teams. In technical organizations with decentralized product teams, one or two designers are grouped with a product manager and team of engineers (Figure 4-1). In more traditional organizations that are organized by business units (for instance, a bank that has units for checking and savings, loans, credit cards, and small business) teams are formed within those units. These teams have their own designer headcount, and fill the roles as they see fit. Designers work much more closely with business people and engineers, figuratively and literally.

There might still be a design head, who remains part of the “corporate” or “headquarters” team, but that person’s role has become more consultative and strategic. This design head helps the different teams understand how they can best embrace design, and helps executives understand the role design can play in the organization, but because of the autonomy given to the decentralized teams, no longer has direct authority over hiring and creative direction.

Benefits of decentralized design teams

The benefits of decentralization are realized immediately, and directly overcome the challenges of centralization. The benefits include:

Because these decentralized business and product teams have been wholly staffed, they have freedom and speed that they couldn’t achieve before. They no longer have to sit in someone else’s queue. They no longer have to wait for approvals. They are in control of their own destiny, and design is part of that.

For the designers, instead of being brought in only after all the important decisions are made, they are now full team members. They participate throughout the product lifecycle, including the agenda-setting requirements development. They contribute to the strategy, and their perspective helps ensure superior product delivery. Their voices cannot be dismissed, because they’re as accountable as any other team member. The “us versus them” they may have felt before falls away. They better understand the challenges that their team members face, and no longer see their job as simply handing off deliverables, but ultimately making the team successful.

Thus, this no longer feels like “work for hire,” but instead something worth investing extra effort in. Being involved throughout the lifecycle means developing a real sense of ownership, and with that comes pride at wanting to do the job right. As they become more deeply aware of capabilities and constraints, their design process takes into account trade-offs. Unlike before, where their designs were altered by others after they had moved on to a new project, now designers are involved in the decisions all the way up to launch, and are better able to maintain the design’s integrity. Post-launch, they can react quickly to refine the work and make it even better. The sense of ownership, deeper understanding of trade-offs, and close collaboration across functions leads to a better product than had been possible before.

Drawbacks of decentralized organization

This sounds like nirvana! What’s not to love? While decentralized models work better in the near term and at smaller scales, over time the following kinds of issues arise:

From the designers’ perspective, the thrill of shipping better work fades as they find themselves iterating on the same problem for a long period of time. There might be new features, but it’s all within the same solution framework, for the same customers, and with the same people, and what was originally invigorating turns stale.

Related to this, designers begin to feel lonely and disconnected. On product teams, where there’s often just one or two designers, they find most of their time is spent with people who don’t really understand them, their craft, or their motivations. Maybe the corporate head of design has instituted attempts at a cross-team design community, but meeting once a month to share work doesn’t feel sufficient. Designers are not sure how they should or could enhance their skills, and such efforts are discouraged by their team’s leadership, because there’s not enough time for those extracurricular activities. After a few shipping cycles, designers wonder, “What’s next?” and “How do I grow?”, and their career path is unclear.

While each product or feature, considered on its own, might be better than what had come before, when pulled together with adjoining products, all those decisions that made sense in isolation end up causing cracks in the overall customer experience. Customers get confused as they have to re-orient with new navigation models, new interface paradigms, new terminology. This trade-off of greater speed and autonomy might make sense in companies where the different offerings aren’t really part of an experiential whole (think Facebook and its many different services, like Events, Photos, Messenger, Games, etc.), but in companies trying to deliver a most holistic experience (such as service industries like retail, banking, health care, and travel), this approach can make the overall experience worse than when things were centralized.

Decentralization also leads to inefficiencies. Instead of a single pattern for, say, displaying and interacting with a photo gallery, each team creates their own photo gallery experience. So not only has there been a ton of wasted effort, there’s confusion on the part of customers who have to relearn how to use different photo galleries.

Whereas centralized design teams could conduct usability (whether or not there was time left to make refinements), it’s often hard for decentralized teams to justify their own user research, beyond quick and inexpensive efforts like online user testing, analyzing logs, and inferences from A/B testing. If there is a user research function in the organization, it has likely remained centralized, which leads to little, if any, real impact.

Centralized Partnership: The Best of Both Worlds

Being centralized is too slow and disempowering. Designers enjoy the variety and collegiality, but ultimately feel stifled by their lack of impact. Going decentralized initially improves matters, in terms of both speed of release and quality, but over time designers grow restless and feel lost, and customers struggle with the lack of cohesion. Teams are thus tempted to re-centralize, but fear they’ll just end up in the same place.

It’s like the Kobayashi Maru,[14] but there’s a lesson to take from Captain Kirk. There’s a third way to run design organizations, one that is slowly gaining wider acceptance. There’s no standard name for it, so we will call it the Centralized Partnership.

For most companies, it makes sense to have business and product teams decentralized. There are very real benefits of autonomy, primarily speed of execution, and decision making that takes into account the actual on-the-ground, day-to-day reality. It’s a force that mostly does good. But it can lead to entropy, where the sum of these seemingly right decisions made in isolation leads to a fractured user experience. A centralized design organization serves as a beneficially opposing force whose holistic perspective can ensure coherence. It’s not uncommon for multiple product teams to work on related, adjacent, or even identical stuff without knowing it. In the Centralized Partnership, the ongoing communication across the design organization makes this apparent early on, and those teams can figure out together how best to tackle it without wasting effort.

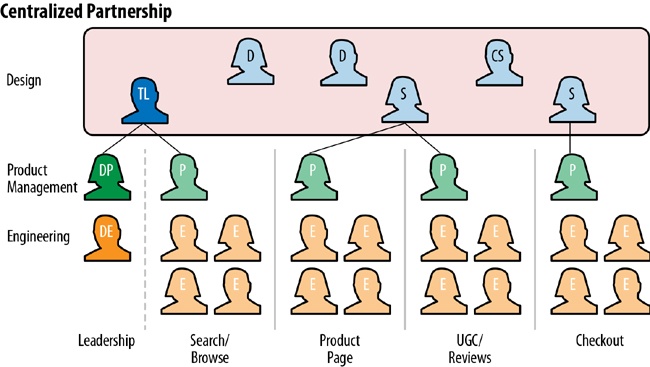

The Centralized Partnership (Figure 4-2) attempts to realize the best of both the decentralized and centralized models. From an organization chart perspective, it is centralized, with all designers in one organization, reporting up through a single point of leadership. And recall what we stated in the last chapter under “5. Support the Entire Journey”—we mean all designers, even if they currently report up through different departments. Designers prefer this hybrid approach because it supports them in their career, professional development, and day-to-day working life. They aren’t isolated on product teams whose members don’t understand what they do, they collaborate with design peers who can improve their skills, and they receive guidance from mentors who help them chart a path.

However, these designers are not part of a general pool of resources that are assigned on a project basis. Instead, they are organized into skills-complete teams, which in turn are dedicated to specific aspects of the business.

The Makeup of a Design Team

Unlike the decentralized model, which orients on staffing design at the individual level (as many decentralized teams have only a single designer), the Centralized Partnership takes a team mindset from the outset. Just like flocks of geese are safer (thanks to their many eyes) and expend less energy (thanks to the reduced drag) than geese flying individually,[15] a gestalt occurs where a strong design team can accomplish much more than the same number of designers working on their own. A Centralized Partnership design organization is composed of these subteams, and the bigger the organization, the more teams there are.

What’s described here won’t be news to people who have worked in design agencies. Though many in-house teams are often dismissive of how agencies operate, there’s much to be learned from companies whose sole purpose was to deliver the best design work. The philosophy discussed here was honed over many years of practice at Adaptive Path (where both authors worked), and has been successfully applied when brought in-house.

Teams range in size from 2 to 7 members. Seven people can take on a large program—consider a generous designer-to-developer ratio of 1 to 5, we’re talking about a program that requires 35 engineers! If it seems the team should be bigger than 7, it’s likely its mandate has gotten too big. Split the team into two, each with a sharper focus.

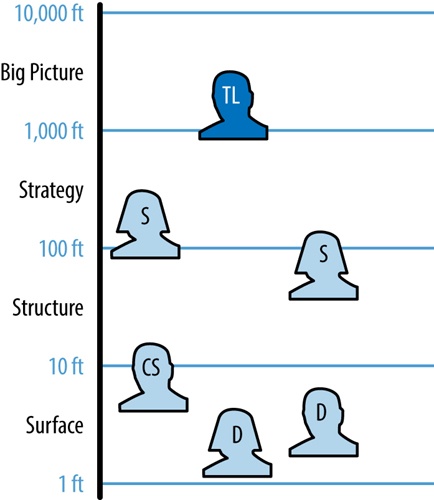

Each team needs a range of skills and the ability to operate across scales (Figure 4-3). While each team does not need to go as broad as the whole design organization, they should still perform well across the core software and communication design practices—research, strategy, ideation, planning, interaction design, information architecture, visual design, and prototyping. From the perspective of scale, the team will not likely be active in addressing the Big Picture, but should be able to operate across Strategy, Structure, and Surface. In the next chapter, we’ll discuss the specific job titles, roles, and responsibilities you will find on these design teams.

Team leads for centralized partnerships

Regardless of size, each design team benefits from a single point of authority and leadership, an individual with vision and high standards who can get the most out of their team. This is the most important role on the team, and the hardest job to do well. Team leads must be able to:

- Manage down

Leads are responsible for overall team performance. They need to create a space (whether physical or conceptual) where great design work can happen. They must coach, guide, mentor, and prod. They address collaboration challenges, personality conflicts, unclear mandates, and people’s emotions.

- Manage across

Design leads coordinate with product leads, business leads, technology leads, and people in other functions in order to make sure their teams’ work is appropriately integrated with the larger whole. They must also be able to credibly push back on unreasonable requirements, and goad when others claim that the design team’s work is too difficult to be delivered.

- Manage up

It’s crucial that these leads are comfortable talking to executives, whether it’s to explain the rationale behind design decisions or to make the case for spending money, whether on people or facilities. Design leads must present clear arguments, delivered without frustration, that demonstrate how their work ties into the larger goals and objectives of the business.

In short, the best team leads are a combination of coach, diplomat, and salesman. And they are folks who, through experience, find they can span the conceptual scale from 1,000 feet all the way down to 1 foot. They oversee the end-to-end experience, ensuring that user needs are understood, business objectives are clear, design solutions are appropriate, and the final quality is high. To achieve coherence, they must integrate efforts across product design, communication design, user experience research, and content strategy. They are responsible for articulating a design vision shared not just by their immediate team, but their cross-functional partners as well. No wonder it’s so hard to find such people!

It’s important to recognize that team lead is not necessarily a people management role. In many companies, reporting structures and team structures are the same, but that doesn’t have to be the case. If it makes sense for the reporting structure to be organized by function (product design, communication design, UX research, etc.), then a broadly skilled design team would be made up of people from across that reporting structure. Thus, the person leading a design team might not be the person conducting performance reviews or responsible for professional development.

Organizing Your Teams

If these design teams were following the decentralized and embedded model, their mandate would simply be inherited from the business or product team of which they were part. In the Centralized Partnership, each team’s mandate must be made explicit, and this is where the “Partnership” comes into play. With what parts of the business are the design teams partnering? Which product teams or business units? Do not consider this lightly. If an approach doesn’t work out, and the design teams need to be re-organized, their efficacy will decline. Here are some guidelines to help figure it out:

- Don’t just mirror the product organization or business units

In order for a team to successfully collaborate with others, it’s important to understand how the rest of the company is organized. However, it’s insufficient to have design teams simply reflect that structure. Organizations grow and evolve over time, and the reasons for how they arrive at a particular structure are varied (e.g., acquisitions, firings, failed initiatives) and might not make sense for the team. A design organization that is not wedded to the structure of the broader company can help maintain a stable customer experience when the inevitable reorganizations occur.

- Organize by customer type

A fallacy is to have designers obsessed with the products and services they work on. Product and service features are just manifestations of a user’s relationship with a company. Instead, designers should be obsessed with their entire user experience. So, organize teams by types of users. Many companies have clearly distinguished audiences—marketplaces have buyers and sellers; banks have personal/consumer, small business, and institutional customers; educational services have teachers, administrators, students, and parents; and so on. When a design team focuses on a type of user, it can go very deep in understanding them, and that empathy leads to stronger designs that fit the users’ contexts and abilities.

How this could work

Imagine work that supports a simple two-sided marketplace, such as eBay, Etsy, or Airbnb, where there are people offering goods or services, and people buying them. The product management organization for this business could have the following teams:

- Growth Team

Acquire new customers, both on the buyer and seller side

- Seller Tools Team

Tools for sellers to list and track sales of their goods and services

- Search/Browse Team

Functionality for shoppers to find items in the marketplace

- Product Page Team

Because this one page is so important, a team is dedicated to it, figuring out how to best incorporate imagery, copy, and reviews

- Shopping Cart and Checkout Team

- Reviews Team

Solicit feedback from buyers and sellers about one another

These teams operate mostly autonomously, using APIs and other services to share data. They may occasionally communicate about specific requirements, such as the Search/Browse and Product Page Teams working with the Seller Tools Team to make sure the information sellers submit is workable in their contexts. Some of these teams focus on a kind of user (Seller Tools for sellers, Search/Browse and Shopping Cart for buyers), and other teams offer functionality that span users (Growth and Reviews).

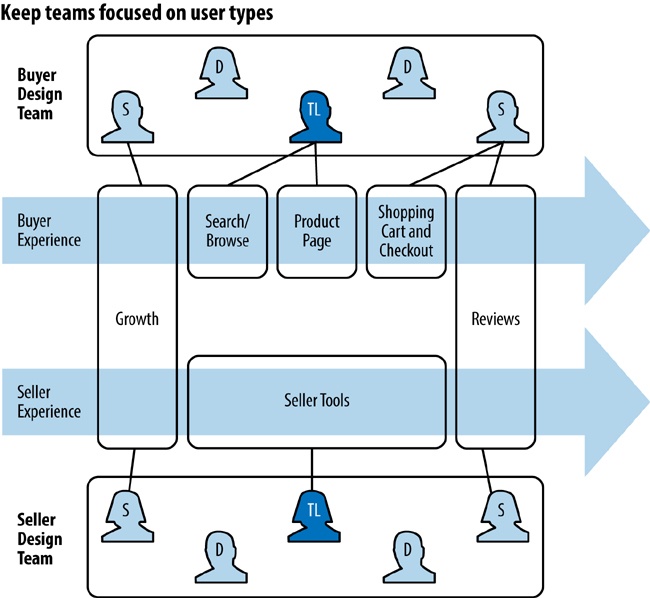

These product teams report up through a VP of Product Management, but otherwise don’t have much structure overlaid. An embedded model would place designers within each product team. While the Centralized Partnership could mimic that, with design teams organized by product, what’s more appropriate is an independent structure overlaid on this product organization, supporting distinct buyer and seller experiences (Figure 4-4).

In this example, certain product teams, such as Search/Browse or Seller Tools, only collaborate with one design team, because their efforts are focused on one user type. Growth and Reviews, however, interact with both Buyers and Sellers, and so those product teams need to collaborate with both design teams. The senior designer focusing on Reviews is also familiar with the tools that precede Reviews on the seller’s journey, and makes sure that the interface for Reviews flows from those tools in an elegant fashion.

This kind of organization may prove quite radical in certain companies. Banks and other financial institutions typically organize their teams around products or lines of business (basic banking, credit and debit cards, loans, mortgages, etc.) that behave as if in silos, and rarely coordinate. However, the same customer is engaging across these products, and can find the lack of coherence frustrating. Putting together a “retail consumer” design team that works across these products should lead to a better customer experience but will be difficult to maintain in the face of a company that incentivizes business units through their specific products’ success. This likely requires executive sponsorship to demonstrate just how crucial a cohesive customer experience is for the whole company.

Organize by the customer’s journey

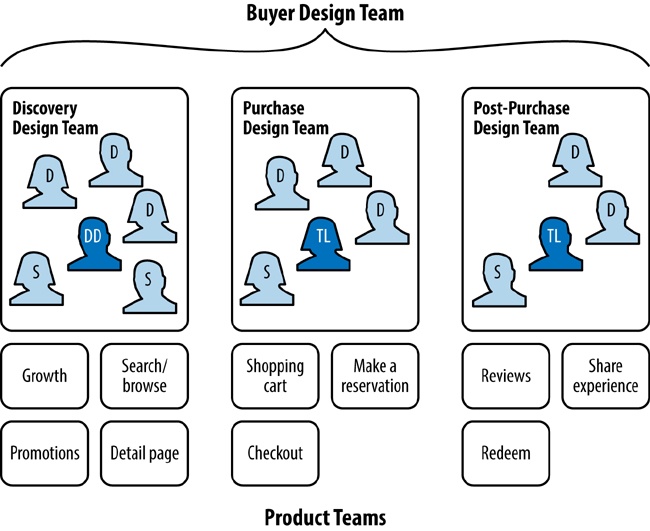

If your company is successful, you’ll need to grow those teams. Keeping in mind what we stated earlier that no design team should have more than seven people, consider splitting them up along a customer’s journey. Using the Buyer Design Team from our simple marketplace, establish subteams such as Discovery, Purchase, and Post-Purchase (Figure 4-5).

This approach to design team organization disregards whether the product or business teams are organized this way. Organizing by the journey allows each team to shift focus from features (search, browse, booking) to the overall experience, and the design work on those features will fit within the broader whole.

These specific teams roll up into a broader “Buyer Design Team.” There is a director of this team (who, in this case, also serves as the lead for the Discovery design team), and team leads for each of the other teams. While all of these smaller teams mostly operate independently, it’s important that they remain in contact, even if it’s just a weekly meeting to share out what each is working on.

The teams shown here are a simplification to illustrate the idea of organizing by journey. In Chapter 5, we will explore the variety of roles and skills in design organizations and their constituent teams.

Commitment is key

As with any successful relationship, the key to making the Centralized Partnership work is commitment. In a centralized world, it’s tempting to move people around depending on what seems to need the most support at that time. The strength of the partnership relies on dedication to seeing designers as members of that business/product team, to developing deep relationships across functions, and to understanding the business’s goals, objectives, and challenges. Only then will designers earn the trust that allows them to engage in the empowered way of a decentralized team, working throughout a product lifecycle, and not be seen as mere stylists to make things pretty at the end.

With that commitment, designers then earn the social capital to push back on the business, either simply when something doesn’t make sense, or when business decisions will affect the overarching customer experience.

That said, many design organizations realize benefits when rotating designers after a sufficient “tour of duty.” Team leads must remain committed, but other team members might change teams after 9–12 months. Designers appreciate this, as it keeps their thinking fresh, exposes them to different styles of leadership, and broadens their skills and acumen. The business benefits because these designers, by bringing their experiences from different parts of the organization together, help weave a coherent customer experience.

Design operations must be made explicit

Traditional organization structures do one thing pretty well—communicate. When centralized, the command-and-control nature enables communication up and down the chain. When decentralized, the autonomous local teams are small enough so everyone knows what’s going on. The Centralized Partnership complicates this, as the design organization likely does not map directly to the rest of the company, and members of specific design teams feel beholden to two sets of stakeholders: their business counterparts and their design leadership.

In particular, this is a challenge for longer-term planning. In a decentralized setup, business teams are responsible for their own designers, and so budget and plan accordingly. With the Centralized Partnership, business teams, which otherwise have control over much of their own destiny, do not have their own designers. This can make them anxious. Quelling their concerns requires conversations about planning, staffing, and the means of collaboration. Such conversations can prove burdensome for design directors and team leads, who need to be able to focus on creative leadership and professional development.

To address this, the design organization needs an operations team, what we call Design Management (or Design Program Management). It is not a big team—you can get by with one Design Program Manager for every 10–15 designers. The charter of this team is to make things go and to ensure that the rest of the design organization as effective as possible. Their work is made up of two big areas:

- Planning and resourcing

Work first with the business or product team leadership to understand roadmaps, backlogs, and other forecasting of activity, and then with the design team lead to figure out capacity. If there’s a disconnect between what the business team wants to do and what the design team can handle, this then gets addressed through adding headcount or bringing on contractors. If it’s not possible to get more people, then Design Program Management spearheads portfolio prioritization exercises in order to make sure the most important work is supported.

- Process and tools

The Design Program Management team is the prime coordinator of how the work gets done, both within the design teams and across functions. They talk with design leads to plan the best process for tackling a design problem. As best practices emerge, they codify them for all the teams to draw from. They drive conversations for standardizing tool use—Photoshop or Sketch? Dropbox or Box? Hipchat or Slack?

This is explicitly not project management although many of the responsibilities are built off a strong project management foundation. Project management should be cross-functional, coordinating across the different disciplines needed to deliver. Though Design Program Managers are often in conversation with the delivery people (whether they’re called agile coaches, project managers, or delivery managers), they themselves are not responsible for delivery. Within a design team, that responsibility falls squarely on the design lead. This means design leads must do some of their own lightweight project management.

Where Does the Design Organization Report?

If you put more than two design leaders in a room and ask them to talk about their work, it’s almost inevitable that the discussion will address the age-old quandary, “Where does design belong in the organization?” The 1990s were a particularly painful time for this question. Many web design teams, along with their engineering partners, reported up through IT, the seeming logic being, “the Web is on computers!” IT, though, was seen as a department in service to the business, and so design by association had very little ability to influence product direction. The other typical placement was in marketing, as many companies primarily saw the Web (and its design) as a platform for talking about products, rather than a product experience in itself.

While we’re mostly beyond this period, the question still remains. Many people advocate design reporting directly into the C-suite, placing it as a peer to product management, marketing, and so on. Given the expanded mandate for design we’ve been preaching, such placement makes sense in theory, but in practice can feel premature. The nascency of design in the enterprise means that it still doesn’t have the critical mass or presence that engineering has, and also there simply hasn’t been the time to develop enough credible senior executive design leaders. Perhaps this paragraph will be revised for this book’s second edition, but there’s a pragmatic reality that, except in very special cases (like Jony Ive and Steve Jobs), design just isn’t quite ready for presence in the C-suite.

Because design’s ascendance is primarily due to the rise of software, many design organizations report up through product management. Based on our conversations with industry leaders, that seems to work fine—teams that report through product are quite successful, even when those design teams are also responsible for design outside of product, such as marketing.

Some organizations don’t have a single head of product management for the design team to report to, and in those instances, may report up through marketing, or even operations. It turns out that more important than reporting lines is that the design team:

Is a single operating entity

Has a mandate to infuse their work through the entire customer experience

Has leadership empowered to shape the team and its activities to deliver on that mandate

New Problems Warrant New Organizational Models

The hierarchical, command-and-control organizational model that served business so well in the 19th and 20th centuries is proving ill-suited to the concerns of a connected-software-and-services economy. Most companies are simply ignoring this, applying outdated approaches and hoping for the best. Some who have accepted the contemporary reality are becoming radically decentralized, or “podular” as Dave Gray put it in his book The Connected Company (O’Reilly, 2014). And while this allows them to operate with uncommon speed, these podular companies typically have trouble maintaining coherent user experiences.

The hub-and-spoke qualities of the Centralized Partnership provide a strong centralized foundation (the hub) upon which to build, but give greater freedom to the teams (the spokes) in their execution to address the challenges under their purview. The push-and-pull between these forces creates a productive tension that keeps the whole organization moving forward without spinning out of control. This organizational model might just prove foundational not just for design, but for all functions within connected-software-and-services companies.

[13] Many companies adopt organization charts unquestioningly, as if they are a natural aspect of enterprises. In fact, the first modern organization chart was designed in 1855 by Daniel McCallum in order to address the communication and coordination challenges of the New York & Erie railroad. McCallum’s principles of management have been widely adopted, though were created for a much different era. For more about McCallum, read https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_McCallum.

[14] Nerd alert: the Kobayashi Maru is the Starfleet Academy battle simulation that tests how officers handle a situation where both choices lead to loss. Captain Kirk, the stud he is, hacks the test, creating a third way that leads to success.

[15] Thanks to leadership and organizational consultant Alla Zollers for the geese analogy.