Types of Business Writing

This section provides specific guidance for different genres of business writing. It doesn’t aim to be comprehensive. Rather, I’ve used input from the business writing survey I conducted for this book to confirm the kinds of things businesspeople write most often, and we’ll focus on those. Here you’ll find guidance on daily writing tasks, like e-mails and instant messages, as well as bigger tasks, like presentations and press releases. For all of them, you’ll find prompts about how to apply some or all of the Seven Steps as you write and refine.

THE BASICS

“Bad e-mail is the bane of my life.”

—SURVEY RESPONDENT

Ask businesspeople what they do for a living, and you’ll get all kinds of answers. Ask them what they do all day, and they’re likely say, “Deal with e-mail.” For most of us, e-mailing at work is as common as breathing. But it shouldn’t be as thoughtless.

DO YOU REALLY WANT TO SEND AN E-MAIL?

It’s easy to fire off an e-mail, but it’s not always the right thing to do. Before you write, consider whether you really should (see the decision tree in “To Write or Not to Write” here). In some situations, you should definitely choose not to send an e-mail.

Don’t send an e-mail when a phone call would work better. Endless rounds of e-mails to clarify, explain, and enlarge can often be prevented if you just pick up the phone.

Don’t fire off an e-mail when you’re angry. Give yourself time to cool off, so you don’t send something you’ll regret later.

Speaking of regret, if there’s anything in your e-mail—anything at all—that might hurt you or your organization, don’t do it. If you know or suspect that someone in your organization has done something illegal, unethical, unwise, or even just embarrassing, don’t e-mail about it. E-mail is not private. It’s discoverable in legal proceedings. Too many businesspeople are still far too careless about what they put in writing, and we see headlines about people incriminating themselves and their organizations in e-mails. There’s no excuse. If you’re not comfortable with reading about it on the front page of the New York Times, don’t put it in writing. Pick up the phone instead, or discuss the issue face-to-face.

MAKE SURE YOUR PURPOSE IS CLEAR

If I could offer only one piece of advice for e-mails, this would be it: make sure your reader knows why you’re writing. How many times have you plowed through a long e-mail trying to figure out what you’re supposed to do with it? How many times have you given up on a long e-mail before you’ve fully understood what it’s about? You don’t want your message on the receiving end of this kind of treatment.

We’re all moving fast when we compose and read e-mails, but it will actually save you time if you stop and think for a moment. Ask yourself, “What am I asking my reader to do?” The answer might be that you want your reader to take some kind of action. Or it might be that you want your reader to understand something. Whatever the answer is, put it into one sentence, and place a version of that sentence at the top of your message. You’ll save your reader and yourself a lot of confusion and follow-up.

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

Consideration for your reader starts with your subject line, which should be concise and specific. A good subject line can help readers prioritize messages and find them later. If your message is especially important, consider putting “important” or “response needed” in the subject line. (See the box “Hints and Tips for Effective E-mails” here for more suggestions about effective subject lines.)

Think from the point of view of your reader as you plan and write your e-mail. Anticipate objections, and make it easy for your reader to reply.

START STRONG AND SPECIFIC

A recent study based on analytics derived from billions of e-mails suggests, surprisingly, that readers’ attention spans seem to be increasing. Since 2011, the average time spent on reading an e-mail has grown by nearly 7 percent. That’s the good news. The bad news is that even with this growth, the average amount of time spent on each e-mail is only eleven seconds.*

With slightly over ten seconds of reader attention, it’s critical that you place your main point in the first three lines of your e-mail. If you count on your reader to scroll to the bottom of your message to get to the request, conclusion, or deadline, you risk losing him altogether.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

That short reader attention span also demands that you keep your message as brief as possible. Narrow down your content to the essentials, especially in an initial message. Follow-up messages can be longer, once you know that your reader is engaged.

You should limit each e-mail to one topic only. Secondary topics risk being buried at the bottom and never seen. The “one topic per e-mail” rule also makes it easier for you and your readers to search and find information in your in-boxes later.

FIX IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

Before you send an e-mail, run though this quick checklist:

Remember that e-mail isn’t private. Don’t put anything confidential in your message. If your e-mail contains anything that could incriminate or embarrass you, your colleagues, or your organization, delete it.

Remember that e-mail isn’t private. Don’t put anything confidential in your message. If your e-mail contains anything that could incriminate or embarrass you, your colleagues, or your organization, delete it.

Is there anyone you ought to copy? Do you really need to copy the people you are copying?

Is there anyone you ought to copy? Do you really need to copy the people you are copying?

If you’re forwarding an e-mail, be sure there’s nothing in it that you shouldn’t share. Especially if you’re forwarding a long thread, it’s worthwhile scrolling down to check.

If you’re forwarding an e-mail, be sure there’s nothing in it that you shouldn’t share. Especially if you’re forwarding a long thread, it’s worthwhile scrolling down to check.

Is it clear to your reader in the first couple of lines what you are asking of her?

Is it clear to your reader in the first couple of lines what you are asking of her?

Have you made your message as concise as possible?

Have you made your message as concise as possible?

Get Your E-mails Opened and Read

“It is very frustrating when I find out that my e-mail was not read (completely), just glossed over. Then again, I do the same thing until I am ready to respond to the e-mail, and then I read it. But if no response is requested . . . or I’m not interested in the topic or discussion . . . I’ll never know if a response was expected from me, because I haven’t actually read the e-mail.”

—SURVEY RESPONDENT

No one wants to send an e-mail that gets no reply. That has happened to all of us, and most of us have been guilty of failing to respond to a message we’ve received. When you send an e-mail, your message is competing with dozens, if not hundreds, of other messages in your reader’s in-box. How do you craft a message that your reader will actually open and read?

It starts with the subject line.

Make your subject line as specific as possible.

Make your subject line as specific as possible.

Use the subject line to state the response required from the reader (e.g., “read only” or “response requested”).

Use the subject line to state the response required from the reader (e.g., “read only” or “response requested”).

State your request within the first three lines of your message. Your opening should include:

The context for the message and the request

The context for the message and the request

The request itself

The request itself

The deadline, if appropriate

The deadline, if appropriate

The recipient’s incentive to continue to read to the bottom

The recipient’s incentive to continue to read to the bottom

Format your message for easy scanning.

If your message is more than a few lines, use bullets and short paragraphs.

If your message is more than a few lines, use bullets and short paragraphs.

Use bold to highlight deadlines and any milestones or intermediate deadlines.

Use bold to highlight deadlines and any milestones or intermediate deadlines.

Using these few simple tricks will make it easier for your reader to process and respond to your message. Over time, you’ll develop a reputation as an efficient communicator who doesn’t waste people’s time, and you’ll earn greater cooperation from your colleagues.

Hints and Tips for Effective E-mails

Patty Malenfant

In this day of short messages on Twitter and one-sentence captions on Facebook photos, the business world would do well to follow the same communication principles when using e-mail. To capture the interest of your reader so your e-mail will be read and you’ll receive the response needed, you must communicate briefly and efficiently. Everyone’s in-box is full, and you want your e-mail to be the one that gets read.

How do you do this? You need to use the e-mail subject line to state why you are sending the e-mail and what type of response you want. By inserting short action instructions before the subject, you can let the reader know what they need to do with your e-mail. Here are some examples:

READ ONLY: This instruction lets the receiver know that the e-mail is just for their information; a response is not necessary, and no action is being requested. The receiver can hold this e-mail until a time in the near future to read it, but they do not have to act on it. Example: READ ONLY: ABC Client Accepts Proposal and Documents Being Finalized.

READ ONLY: This instruction lets the receiver know that the e-mail is just for their information; a response is not necessary, and no action is being requested. The receiver can hold this e-mail until a time in the near future to read it, but they do not have to act on it. Example: READ ONLY: ABC Client Accepts Proposal and Documents Being Finalized.

RESPONSE REQUIRED: This instruction is for those e-mails where the receiver needs to do more than read—they need to reply. You are waiting for their response so you can take an action on your end. Example: RESPONSE REQUIRED: ABC Client Negotiated Contract Down $250.

RESPONSE REQUIRED: This instruction is for those e-mails where the receiver needs to do more than read—they need to reply. You are waiting for their response so you can take an action on your end. Example: RESPONSE REQUIRED: ABC Client Negotiated Contract Down $250.

ACTION REQUIRED: This instruction lets the reader know that they need to do something with your e-mail beyond reading and responding—they need to take action. If you want to highlight a deadline for the action, you can add “Deadline” plus that date at the end of the subject line. Example: ACTION REQUIRED: Contract Proposal Final Approvals—Deadline July 15.

ACTION REQUIRED: This instruction lets the reader know that they need to do something with your e-mail beyond reading and responding—they need to take action. If you want to highlight a deadline for the action, you can add “Deadline” plus that date at the end of the subject line. Example: ACTION REQUIRED: Contract Proposal Final Approvals—Deadline July 15.

EOM: “EOM” stands for “End of Message.” You will use this when you want to send only a quick message, comparable to a text message, but you are using e-mail. There is nothing in the body of the e-mail to review or requiring a response; in fact, there is nothing in the body of the e-mail at all, since the whole message is the subject line. Example: Wrapping up call—will be 15 minutes late for lunch EOM.

EOM: “EOM” stands for “End of Message.” You will use this when you want to send only a quick message, comparable to a text message, but you are using e-mail. There is nothing in the body of the e-mail to review or requiring a response; in fact, there is nothing in the body of the e-mail at all, since the whole message is the subject line. Example: Wrapping up call—will be 15 minutes late for lunch EOM.

Now that you have mastered the subject line of your e-mail, you need to be sure the content in the body succinctly communicates to your reader what they must know and/or do. You will have no more than three short paragraphs of two to four sentences each. Introduce the e-mail with a professional greeting and close with the same before your name and title, as appropriate for your organization.

In the first paragraph, give your reader any background information they need to know. The second paragraph follows with the challenge at hand or what is needed. Use the closing paragraph to cover any remaining questions or comments about the follow-up required.

By following these easy tips, you can now go forth and be sure that your e-mail will be the one everyone wants to read!

Patty Malenfant is a human resources leader for a Fortune 500 hospitality company in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area.

The Etiquette of E-mail Writing

Rosanne J. Thomas

Face-to-face communication is considered the best way to build relationships and deliver important messages. But the speed, convenience, and accuracy of text-based communication now make this mode the number one choice among professionals. We have a myriad of ways to communicate via text, but in business, e-mail is still the go-to method. However, there is a lot at stake with this mode of communication. Professionals at the highest levels have suffered extreme personal, financial, and health consequences as a result of carelessly crafted, hastily sent e-mails. And, of course, e-mail lives forever. How can we protect our reputations while maximizing the benefit of e-mail communication? Here are some guidelines.

Apply the standard of “if you would not say it face-to-face, do not write it in an e-mail.” Studies show that people are much “braver” when communicating from behind a screen and that the lack of nonverbal cues often makes e-mails sound more aggressive than intended.

Apply the standard of “if you would not say it face-to-face, do not write it in an e-mail.” Studies show that people are much “braver” when communicating from behind a screen and that the lack of nonverbal cues often makes e-mails sound more aggressive than intended.

Direct your message properly. Double-check e-mail addresses. Do not send “Reply All” messages unless absolutely necessary. Use “BCC” (blind carbon copy) ethically, and not to mislead your primary recipient into thinking that the e-mail exchange is confidential.

Direct your message properly. Double-check e-mail addresses. Do not send “Reply All” messages unless absolutely necessary. Use “BCC” (blind carbon copy) ethically, and not to mislead your primary recipient into thinking that the e-mail exchange is confidential.

Read through e-mail threads completely before responding or forwarding. Use greater formality in e-mail composition with clients, company executives, persons from other cultures, and those you do not know well. Include an appropriate salutation and closing. Make sure sentences are properly structured. Observe the rules of capitalization and punctuation.

Read through e-mail threads completely before responding or forwarding. Use greater formality in e-mail composition with clients, company executives, persons from other cultures, and those you do not know well. Include an appropriate salutation and closing. Make sure sentences are properly structured. Observe the rules of capitalization and punctuation.

Allow words to convey their meaning and emotion. Steer clear of emoticons and emojis in professional e-mails. Avoid using all capital letters, no capital letters, multiple exclamation points, bold typeface, bright colors, or flashing text.

Allow words to convey their meaning and emotion. Steer clear of emoticons and emojis in professional e-mails. Avoid using all capital letters, no capital letters, multiple exclamation points, bold typeface, bright colors, or flashing text.

Proofread all e-mails. Use but do not rely solely upon grammar-check and spell-check tools. Read e-mails aloud to be sure they reflect your intended tone.

Proofread all e-mails. Use but do not rely solely upon grammar-check and spell-check tools. Read e-mails aloud to be sure they reflect your intended tone.

Respond to e-mails promptly. If you cannot respond at least by the end of the day, have an “Out of Office” message automatically sent back to the recipient. This will help preserve the relationship.

Respond to e-mails promptly. If you cannot respond at least by the end of the day, have an “Out of Office” message automatically sent back to the recipient. This will help preserve the relationship.

Rosanne J. Thomas is the founder and president of Protocol Advisors, Inc., of Boston, Massachusetts, and the author of Excuse Me: The Survival Guide to Modern Business Etiquette (AMACOM, 2017).

Requests

Most communications in business are requests of one kind or another. Whether you’re asking for help or just for a bit of the reader’s attention, taking the time to plan and craft your request—rather than winging it—can significantly increase your chances of getting what you want and can save you time and hassle over the long run.

WHAT DO YOU WANT?

The fundamental purpose of any request—be it for assistance, information, or any other goal—is to enlist the cooperation of the reader. In order to do that, you need to be very clear about what you’re asking. This point sounds ridiculously simplistic, until you consider the number of messages you’ve received that have left you wondering, “What exactly do you want from me?” Unless your request is very straightforward, it’s worth taking a minute to clarify it in your own mind. If you’re asking for help, is it clear what kind of help you want? What, specifically, would you like the reader to do, and when?

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

Understanding your objective and stating it clearly is only half of the communication equation. The other half is understanding your reader: her potential attitude toward your request and what it might take for her to say yes. If you can anticipate her response, you can address any potential objections she might raise and motivate her to respond positively to your request.

START STRONG AND SPECIFIC

You should state your request early in your message, to orient the reader and allow her to decide whether to read your message now or wait until she can give it more time and attention.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

In addition to being clear about your request, you should be sure to provide any information your reader might need to make a decision. Include any necessary documentation related to your request. Let the reader know how you prefer to be contacted, if it’s not apparent.

Explaining the reason behind the request might help your reader respond favorably. Letting the reader know how important the request is to you can also motivate her to respond. How will you benefit if she grants your request? How might she benefit?

Your request should also include a deadline, if applicable and appropriate. Be sure your deadline is specific—asking for a response “ASAP” makes it easy for your reader to forget about your request. If you have a particularly tight deadline, explain the reason behind it. People will work harder to meet a deadline if they understand the reason for it.

CHECK IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

Before you send off your request, check it over to make sure nothing feels wrong:

Make sure your request comes early in your message and is clearly understandable to the reader.

Make sure your request comes early in your message and is clearly understandable to the reader.

Use a courteous, not demanding, tone. Remember, you’re trying to gain cooperation from your reader.

Use a courteous, not demanding, tone. Remember, you’re trying to gain cooperation from your reader.

Don’t take your reader or his attitude for granted, and don’t assume he’ll say yes to your request.

Don’t take your reader or his attitude for granted, and don’t assume he’ll say yes to your request.

Remember to thank your reader.

Remember to thank your reader.

SAMPLE E-MAIL WITH A REQUEST

To: John Mottola

Date: April 17, 2019

Subject: Can you share configuration for BBL?

Hi Jack,

I’m writing a proposal for Evergreen, and I’m wondering if you could share the details of how you configured the package for the BBL installation. I’d like to do something similar for Evergreen. I want to submit the proposal on April 26.

I looked on the CRM, but I don’t see a lot of detail there. Can you shoot me an e-mail or spend a few minutes on the phone with me?

Thank you!

Kelby

Escalated Request When a Deadline Is Approaching

When a deadline is looming and you haven’t had the response to your request you need, it’s time to escalate. An escalated request follows the same basic principles as an initial request, but it’s pared down to the essentials and it makes a special appeal to the reader.

Edit the subject line. When you send a follow-up to your request, edit the subject line to let the reader know the deadline is looming. If your original subject line was “Can you provide data for the report?,” you might edit it to say “Deadline Friday: Can you provide data for the report?” or “Reminder: Can you provide data for the report?”

Edit the subject line. When you send a follow-up to your request, edit the subject line to let the reader know the deadline is looming. If your original subject line was “Can you provide data for the report?,” you might edit it to say “Deadline Friday: Can you provide data for the report?” or “Reminder: Can you provide data for the report?”

Keep it short. Your follow-up request should be brief and should contain the most essential information the reader needs to carry out what’s being asked. Don’t get bogged down in details.

Keep it short. Your follow-up request should be brief and should contain the most essential information the reader needs to carry out what’s being asked. Don’t get bogged down in details.

Acknowledge that the reader is busy.

Acknowledge that the reader is busy.

Let the reader know why the request is important to you or to the organization.

Let the reader know why the request is important to you or to the organization.

Let the reader know why you’re asking him and not someone else—what can he do that no one else can do for you?

Let the reader know why you’re asking him and not someone else—what can he do that no one else can do for you?

Restate the deadline, and explain why it’s important.

Restate the deadline, and explain why it’s important.

Offer to help. If there’s any way you can make it easier for the reader, offer to do so.

Offer to help. If there’s any way you can make it easier for the reader, offer to do so.

If appropriate, indicate that you’ll follow up again shortly, maybe with a phone call.

If appropriate, indicate that you’ll follow up again shortly, maybe with a phone call.

Be sure to say “thank you.”

Be sure to say “thank you.”

SAMPLE E-MAIL WITH AN ESCALATED REQUEST

To: John Mottola

Date: April 23, 2019

Subject: Deadline Friday: Can you share configuration for BBL?

Hi Jack,

Just following up on this. I’d like to use the same configuration you used for BBL in my proposal to Evergreen, which is due on Friday the 26th. I know you’re swamped with JWB right now, but your insight here could really help us close the deal. Even just the server information would make a big difference.

I’ll give you a call tomorrow.

Thank you for your help!

Kelby

Bad News Messages

Good news messages are easy to write, but conveying bad news can be rough. The key here is to save the reader’s feelings to the greatest extent possible. That means opening with a buffer—a thank-you, if appropriate, or some kind of statement of appreciation. To avoid giving the reader false hope, though, you should transition very quickly to a diplomatic and kind statement of the bad news. If appropriate, it’s fine to express regret over the news, but not an apology. If there’s some hope of good news in the future, make sure you communicate that hope conservatively, without making a firm commitment. Close with a statement of goodwill.

Dear Erik,

Thank you for submitting the proposal for creating a task force on recruiting. You suggested some great ideas, but unfortunately we have to prioritize expanding the product line this season and we don’t have the resources right now.

I would like to return to this idea once we have the product line resolved. Let’s stay in touch about it.

Thanks again,

Mack

Instant Messages

Instant messaging or chatting is nearly as quick and easy as talking, but it isn’t talking—it’s writing, and it requires a little care. No matter what IM or chat app you’re using, these guidelines can help make your messages more productive and efficient.

IS IM THE RIGHT MEDIUM?

IM is almost too easy to use. It’s the default medium of communication for a lot of us at work, but it’s not always the most appropriate one. Before you ping a colleague, it’s a good idea to slow down long enough to ask yourself a few questions: “Do I really need this answer immediately? Is it worth interrupting my colleague to get it in this way? Would it be more efficient to save up a few questions and ask them all at once? Would it be better to let my colleague answer in his own time instead of insisting on a response now?” It’s also worth considering what kind of record, if any, you’ll need of the discussion with your colleague. Some messaging programs preserve your message history when you shut down your computer, but others don’t. So if you want an easily accessible record of your exchange, instant messaging might not be the best choice of medium.

MIND YOUR MANNERS

Respect the availability status of your colleagues, and if it’s red, don’t send a message unless it’s an absolute emergency. Your colleague might be in the middle of a Webex or videoconference and not appreciate the distraction on the screen, or she might be concentrating on finishing a task.

You also need to be aware of tone when you’re sending messages. It’s easy to slip into a very casual tone. That’s fine when you and your colleague are on the same wavelength, but take care you don’t use a super-casual tone with someone you don’t know well. Be especially careful if you have more than one chat window or channel going at once.

Remember that you’re at work. Instant messaging can be fun, but you’re not on Facebook or Instagram. Respect your colleagues’ time, and exercise restraint when sharing to group chats or channels; remember that everyone is trying to get their work done.

WATCH WHAT YOU SAY

Even when you’re pinging with good work friends, remember that instant messages are official business communications. They are not confidential. They’re the property of your company, and many companies monitor them. You’re probably cautious about cursing in the office; you should exercise the same caution when you’re messaging. One popular instant messaging program warns users: “Keep your conversations limited to what can be safely said in an elevator or a crowded restaurant.” Keep it appropriate.

USING INSTANT MESSAGING EFFICIENTLY

A few little tricks can help improve the efficiency of your instant messaging. Before you launch into a long message, ask your colleague if she’s there and available. Make your “Are you there?” message more specific by letting your colleague know what you want to ping about. Instead of “Hey, got a second?” try “Hey, got a second to review the XYZ agreement?” or “Hey, got a second to read something for me?” or “Hey, got a second to show me how to use that software?” And be frank about what you’re asking for; don’t type “qq?” if what you really want is to discuss whether or not to fire a vendor or some other large topic.

Presentations

Thirty million PowerPoint presentations are given every day throughout the world. How can you make yours memorable?

PINPOINT YOUR PURPOSE

Attention can wander during a presentation, so it’s important that you know exactly what you want to get from yours. As an exercise, try creating a one-sentence objective for the presentation, such as “By the end of the presentation, I want the audience to understand that our solution offers more tools than the competition’s does and can be customized for their needs” or “By the end of the presentation, I want x members of the audience to request an onsite demo” or “By the end of the presentation, I want to have cleared the obstacles to partnering on this project.” Try to make your objective as active as possible, in order to avoid building a presentation that’s essentially an information dump. What do you want your audience to do as a result of seeing your presentation?

WRITE FOR YOUR AUDIENCE

As you work on your slides, think from the point of view of the people who will have to look at them. What are they expecting from your presentation? What information do they need? How would you feel sitting through this presentation? How can you make the slides easy for the audience to read and ensure that they reinforce your main points? Let your understanding of your audience’s needs guide the preparation of your slides.

ORIENT YOUR AUDIENCE AT THE BEGINNING

The opening of your presentation is an especially critical moment. Presumably you have everyone’s attention at the beginning. No one has had a chance to get bored, to get distracted by their phone, or to grow worried about the work they’re not getting done because they’re sitting in this presentation. Use this moment to let your audience know what will be covered in the presentation. Insert an outline slide at the beginning, and return to it throughout the presentation to help your audience with transitions and help them pace themselves in terms of energy and attention.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

There’s a strong impulse when you’re preparing your slides to include too much content. Research has shown that people typically remember only four slides from a twenty-page deck.† That’s not very encouraging news if you’re putting your heart and soul into an informative presentation, but from a strategic point of view, it’s good to know. Rather than packing your presentation full of facts, you’re better off choosing a few key points you want your audience to remember, and organizing the presentation around those. Think of your PowerPoint deck as a set of prompts for your performance rather than as a repository for complete information.‡

Set up your slides as a visual aid for when you’re making a speech or presentation, not as a trove of data. When presented with a very text-heavy slide, people will typically space out or stop listening and read the slide (people can read faster than you can talk). If you want to provide detailed information to your audience, you can make and distribute a leave-behind deck that contains your entire talk. For the presentation itself, keep your slides concise and the focus on you.

USE VISUALS EFFECTIVELY

Think visually as you create your slides.§ There’s no need to convey information only through words—think about how you can use images and graphics to get your points across. But be careful with graphs and charts: don’t present graphics that are too small or detailed for the audience to see easily or understand quickly. If you have an important chart or table that is complex, present a simplified version of it on your slide and give the audience the full version, printed on paper, to examine more closely.

IF SOMETHING FEELS WRONG, FIX IT

Proofread your slides very carefully. Noticing a typo for the first time when you’re standing in front of a group is a ghastly experience, and it makes you look bad. If possible, ask someone who is not familiar with the content to proof the presentation for you.

Allow yourself time to rehearse the presentation and revise it, even if you feel pretty comfortable about the content. Notice transitions that aren’t smooth, areas where your content seems thin, sections that drag. Rehearsing can give you more confidence and will improve your audience’s experience by helping you improve your slides.

SLIDE REVISION CHECKLIST

Choose readable fonts, and limit the number of fonts you use. Stick to a few basic, easy-to-read fonts, no more than two different fonts per slide.

Choose readable fonts, and limit the number of fonts you use. Stick to a few basic, easy-to-read fonts, no more than two different fonts per slide.

Use animation and sound sparingly and only if they support the message of your presentation. If they enhance the meaning and clarity of your presentation, use them. If they compete with your content, don’t.

Use animation and sound sparingly and only if they support the message of your presentation. If they enhance the meaning and clarity of your presentation, use them. If they compete with your content, don’t.

In bullet points, use parallel grammatical constructions to help your audience follow your ideas.

In bullet points, use parallel grammatical constructions to help your audience follow your ideas.

Use formatting like bold and italics sparingly and consistently. Too much of this kind of formatting can make your slides hard to read.

Use formatting like bold and italics sparingly and consistently. Too much of this kind of formatting can make your slides hard to read.

For sample presentations, please visit me at www.howtowriteanything.com.

Creating Visuals

Not all business communication occurs through writing—a lot occurs through visuals. In fact, words aren’t always your best tool. Sometimes data is easier to understand if it’s represented graphically. You don’t have to be a graphic designer to learn the language of visual communication.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT GRAPHIC

There are lots of graphics options for you to choose from: photos and other images, as well as different kinds of charts and graphs. The type of graphic you choose will depend on your data and the story you want to tell with it.

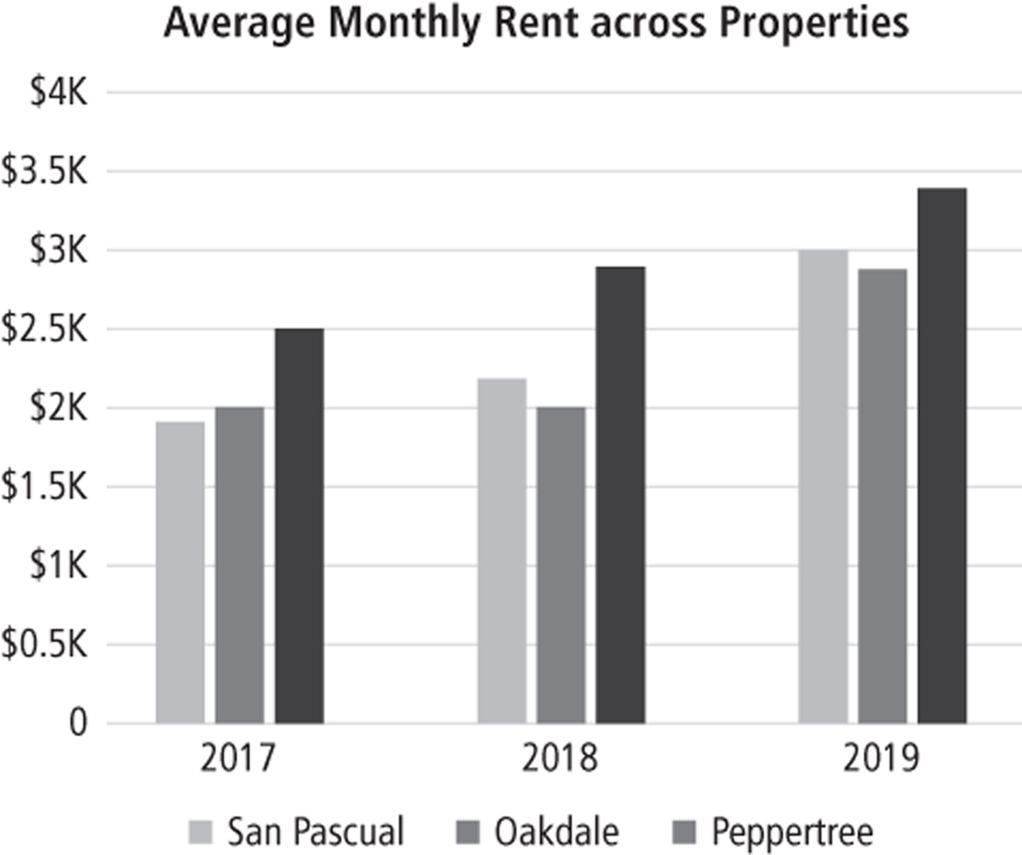

COLUMN CHART

A column chart lets you compare values using vertical bars.

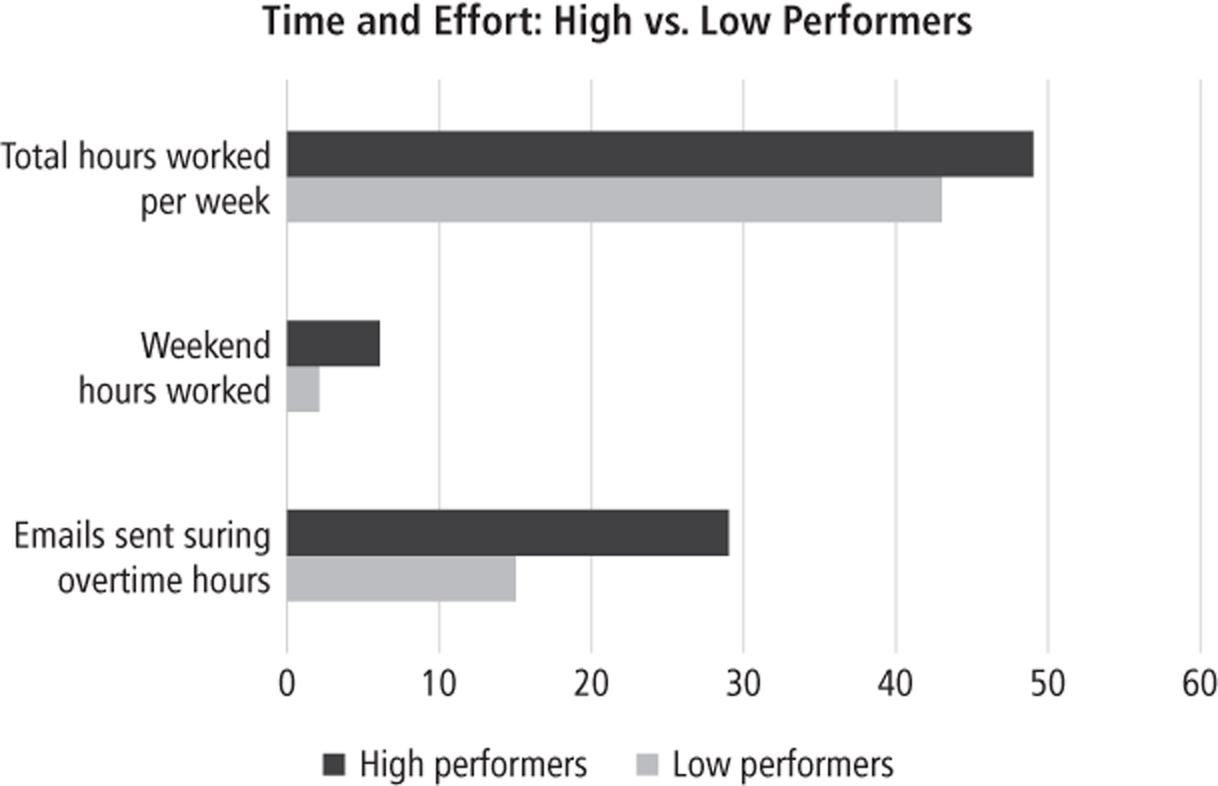

BAR CHART

A bar chart lets you compare values using horizontal bars. The layout of a bar chart makes it better suited than a column chart for data with long labels.

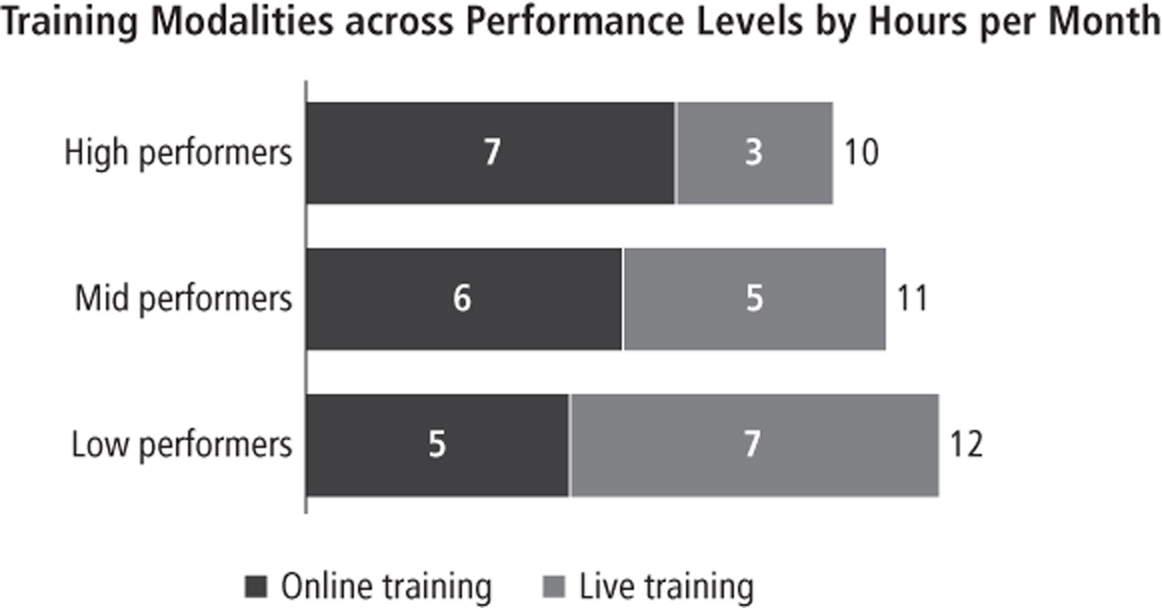

STACKED BAR CHART

A stacked bar chart breaks out the components of a total number, so you can compare segments as well as totals.

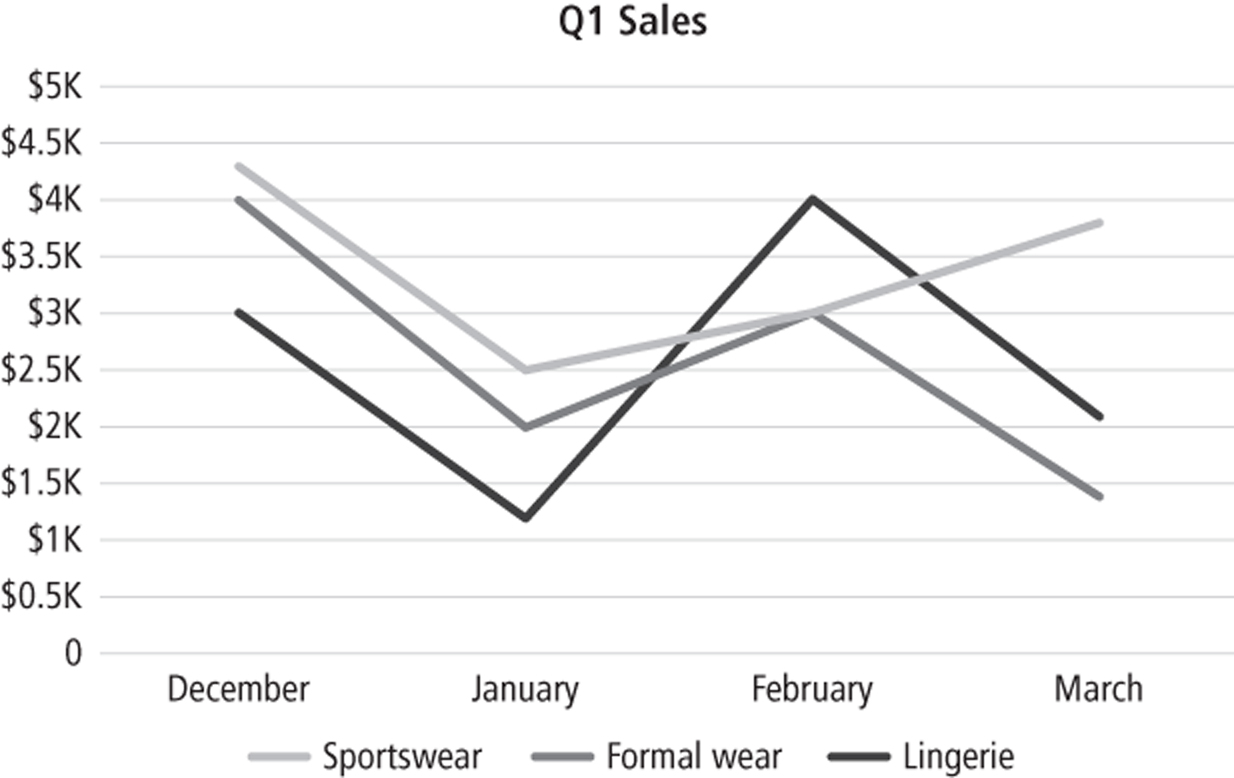

LINE CHART

A line chart is used to track and compare values over time. It can show small increments of time more effectively than a bar chart can.

PIE CHART

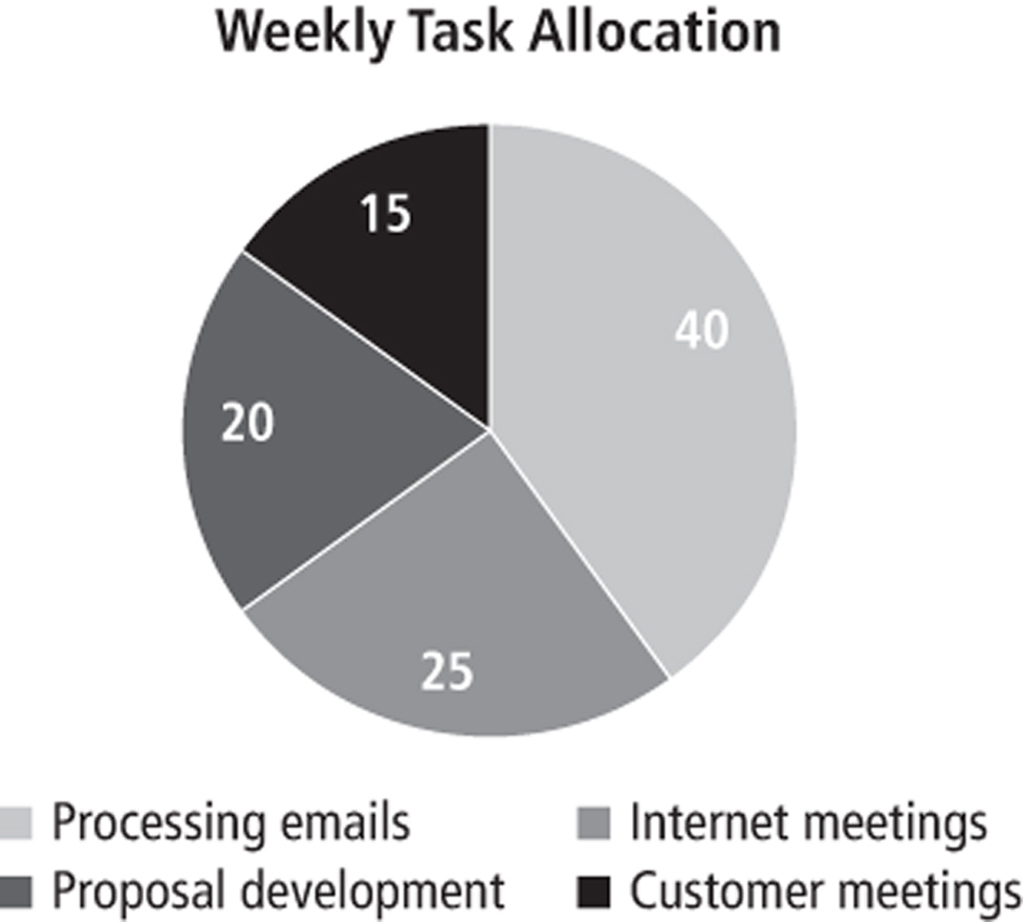

A pie chart is a circle divided into slices, useful for showing numerical proportion.

DOT OR SCATTER PLOT

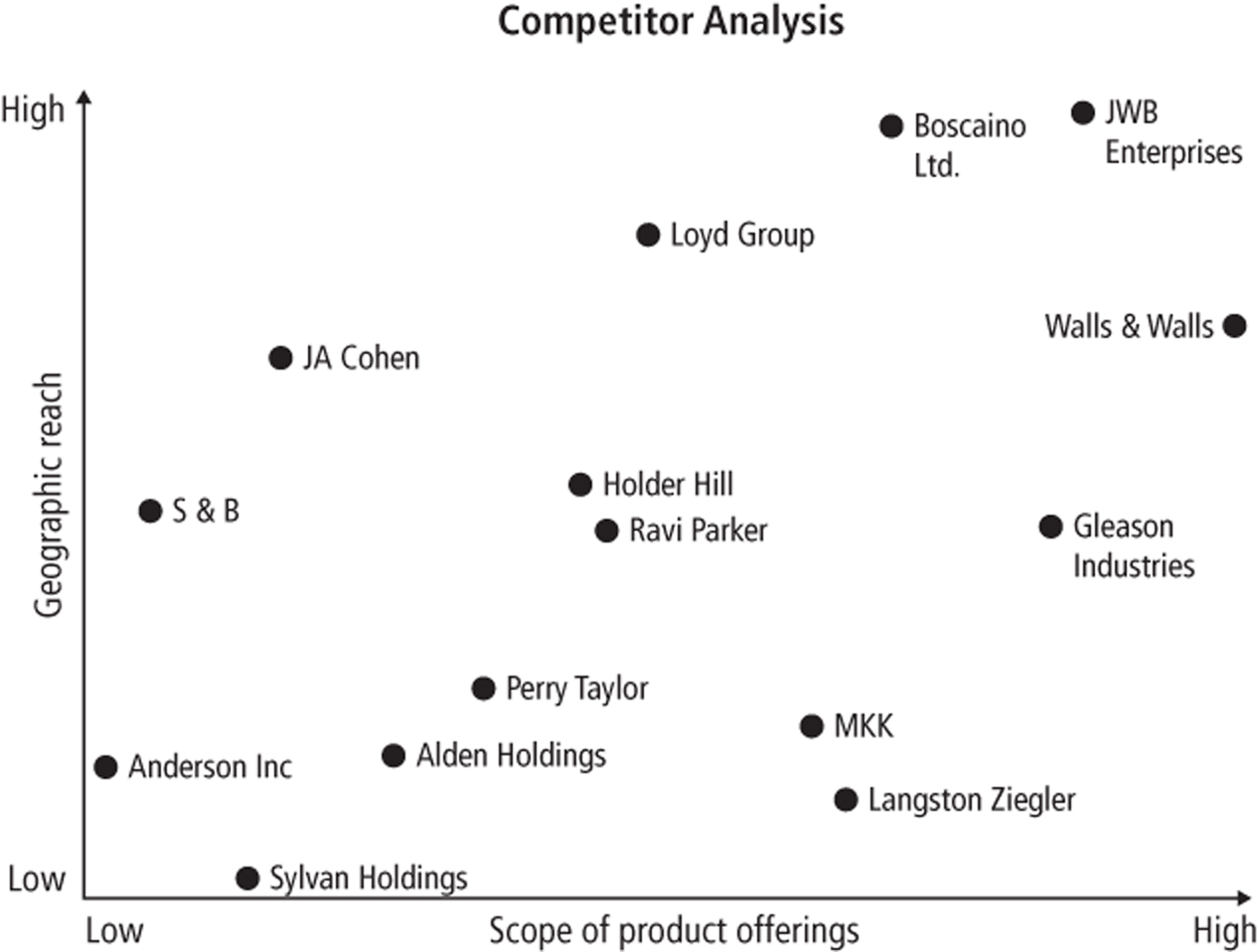

A dot or scatter plot shows data positioned on vertical and horizontal axes. It might be used to show the effect of one variable on another. In this example, a company is using a scatter plot to evaluate its competitors on two dimensions: geographic reach and scope of product offerings.

WATERFALL CHART

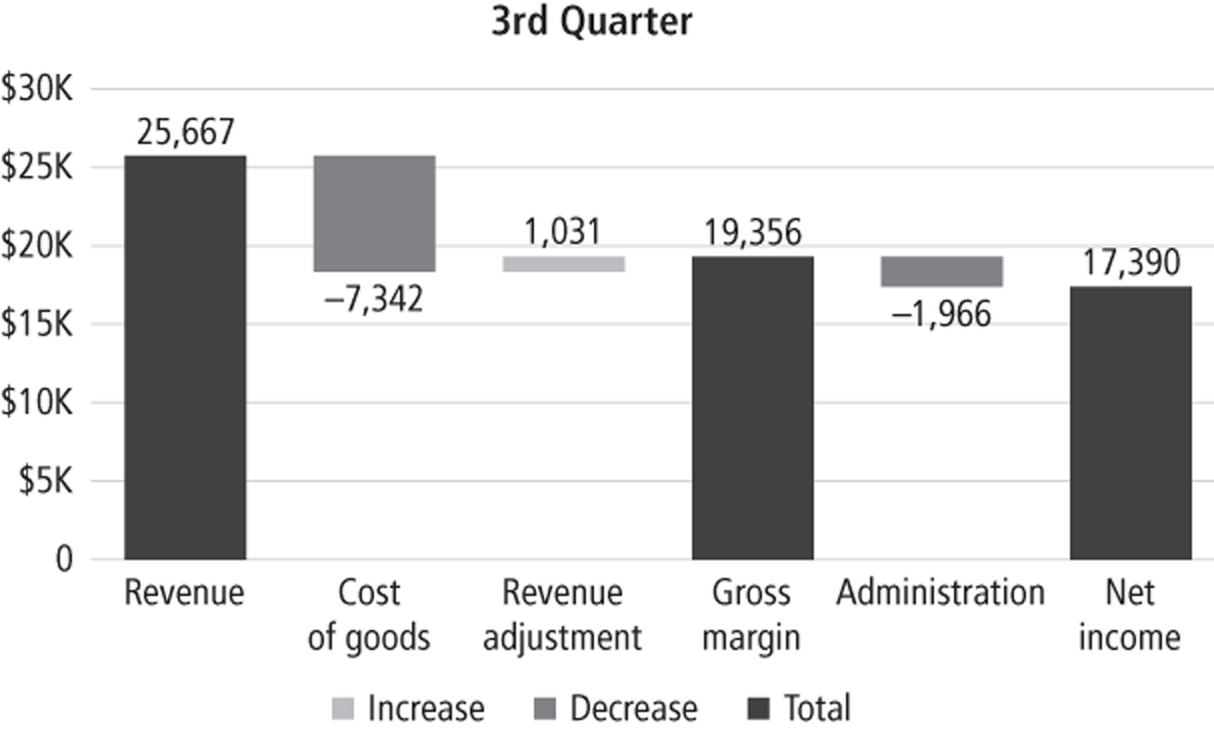

Waterfall charts show how the cumulative effects of different inputs contribute to a net value.

FUNNEL CHART

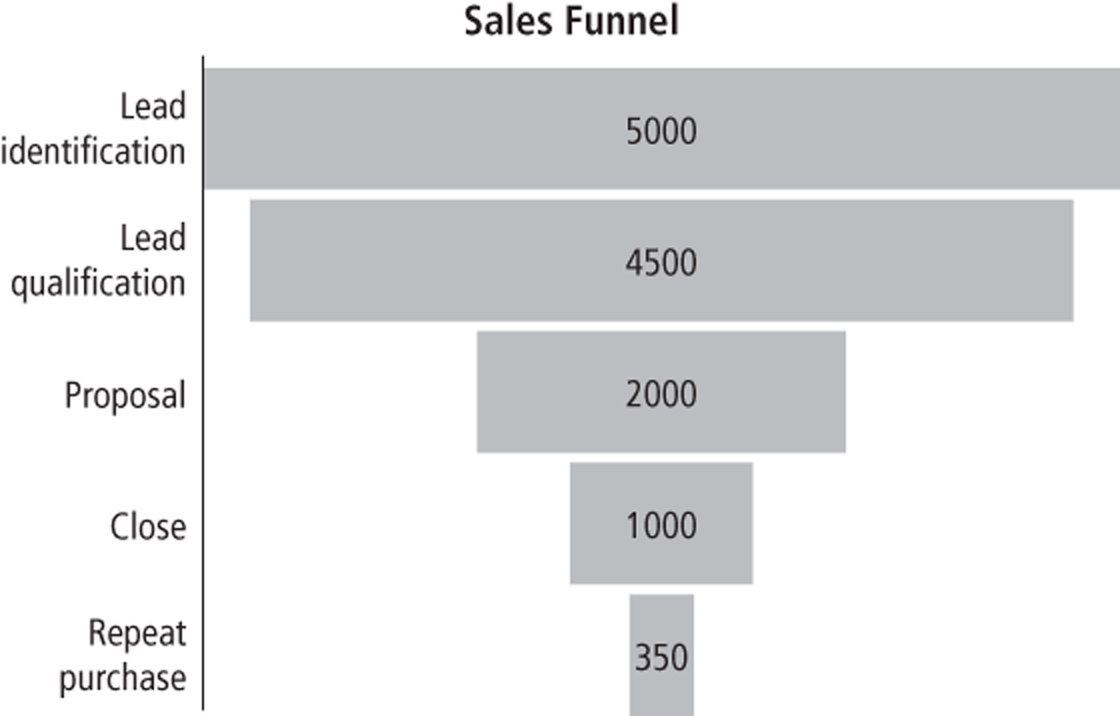

Funnel charts are often used in sales to show the potential revenue for each stage in the sales process. They can help you identify areas in the process where value is at greatest risk of being lost, and they can help identify an unhealthy sales funnel. In this example, the qualification process is not weeding out many prospects, which leads to many rejected proposals.

MAKE SURE YOUR WORDS AND GRAPHICS COMPLEMENT EACH OTHER

When you use words and graphics together, you need to make sure they work together in harmony and support each other. The first and most obvious rule is that the content of your words and graphics should be consistent. For example, if you’re calling out some numbers from a graphic, make sure those numbers are accurate.

Avoid repeating the content of the graphic in your prose. If you’re simply going to rehash the contents of the graphic in writing, there’s not much point in including the graphic. Instead, strategically use information from your graphics to support the arguments you’re making in prose.

Proposals

Businesses of all kinds create proposals for potential customers and clients—for example, to bid for work, to outline the scope of a job, or to state a price. The content of a sales proposal will vary widely, depending on the kind of business you’re in, and most businesses have a standard format they use. Check to see if your organization has a proposal template, then use these suggestions to make it as compelling as possible.

GET THE ASK CLEAR

If you write a lot of proposals, it’s tempting to go on automatic pilot, filling in the various sections with numbers and other details. That approach is probably fine a lot of the time, especially if you provide the same service or product over and over. But it’s worth mentioning here that you should pay attention to your prospective customer, and make sure your proposal reflects your understanding of their needs.

WRITE FOR YOUR READER

If you’re preparing a proposal, it’s probably at the request of someone you’ve talked to at your potential customer. Needless to say, you should consider carefully all the information your contact has given you. You should also go beyond that. Depending on the situation, it’s very likely that others in the organization will review your proposal. Who might they be, and what might they be concerned about? If your contact person is not the decision-maker, it might be worthwhile to ask who else will review the proposal.

Everyone reviewing a proposal will be concerned about cost, but don’t assume that cost is the only factor. Really think about your reader’s needs, and ensure that your proposal addresses them.

GET THE CONTENT RIGHT

Decide how you want to present estimates in your proposal. Sometimes estimates are binding. In other cases, the proposal contains a clause stating that the final cost may vary depending on a variety of circumstances. You should date your proposal and include an expiration date for the price quoted, so that you don’t bind yourself to a price forever and there’s no misunderstanding with the customer.

If there’s a risk of cost overruns, address that risk directly and outline the factors that might cause them, including unanticipated circumstances on the job or changes in the customer’s requirements.

If you feel the customer isn’t entirely sure what they want, consider providing several different estimates for different options. Some companies routinely include add-ons in proposals, which can lead to more business, but add-ons can also annoy customers if they feel they are being upsold. Any add-ons you suggest should clearly address the customer’s needs as you understand them.

CHECK IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

If you’re using a template for your proposal or repurposing a proposal you’ve used before, have a look before you send it to make sure you’re including complete information and that you’re not inadvertently leaving in the details of previous proposals, including the names of other companies and prices for other jobs.

Also check to see that you’ve included everything, and that your numbers add up accurately. Errors can be embarrassing and sometimes costly.

For sample proposals, please visit me at www.howtowriteanything.com.

RFPs

Some organizations will prepare and circulate a Request for Proposals (RFP) in search of a vendor to do a particular job, usually for jobs of a significant size. Some organizations that use public money are mandated to use an RFP in the bidding process.

If you’re responding to an RFP, be very sure you follow its requirements exactly. Any deviation can throw you out of the running without further consideration.

A long sales proposal in response to an RFP may include the following elements:

Letter of transmittal

Title page

Executive summary

Description of current problem

Description of current method

Description of proposed method

Analytical comparison of current and proposed methods

Equipment requirements

Cost analysis

Delivery schedule

Summary of benefits

Breakdown of responsibilities

Description of vendor, including team bios

Vendor’s promotional literature

Contract

BUSINESS RELATIONSHIPS

Introductions

Providing written introductions for colleagues and associates is a vital part of business networking. A good introduction can get the dialogue started in a productive way.

Before we go any further, a note of caution: don’t make an introduction if you’re uncomfortable about doing so. An introduction is a kind of recommendation: you’re essentially saying, “This person will be worth your time to talk to.” Don’t put your reputation on the line if you have any doubts about either party.

BE CLEAR ABOUT WHAT YOU’RE ASKING

When you introduce two people, it’s your responsibility to set up the relationship. You should make it clear not just who the parties are, but why you’re making the introduction in the first place.

Often the introduction will be of more benefit to one party than the other. Perhaps someone would like to do an informational interview, asking for information about a business or an industry or seeking career advice. When that’s the case, be honest about it, and be sure you thank the party who (you hope) will provide the help.

CONSIDER BOTH OF YOUR READERS

Before you write the introduction, it’s important to get permission from both of the parties involved, especially if you feel that either might be uncomfortable or unwilling. If someone has asked you to make the introduction, be sure you understand what they’re hoping to get from the new relationship. Particularly when you’re requesting a favor from someone, ascertain that they’re willing to provide it before you put them on the spot with an introductory e-mail. Contact both parties separately to assess the level of interest and request permission to make the introduction.

START STRONG

Address both readers in your salutation. It’s usually wise to place the name of the senior or more powerful person first.

Start by orienting both readers. Say explicitly that you’re making an introduction, and explain why. Even though you’ve contacted both parties before writing the e-mail, remember that your readers don’t know each other and will need to be reminded about the reason for the introduction. Mention how you met each of the parties, if that seems relevant.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

In most cases, your introduction doesn’t have to be long. Offer a bit of information about both of the parties being introduced. In a quick e-mail, just a sentence can be enough. Suggest how this new connection might benefit each person. However, if it is clear that one party will benefit far more than the other, be straightforward about that, and thank the person who’s granting the favor. If you are introducing a recent graduate to an executive, for instance, it is clear that the introduction will likely have greater business benefit to the younger person.

If you want to provide background information about either party, consider including a bio or a link to that person’s website.

Finally, leave it up to your readers to decide on the next steps. Don’t say anything to suggest that either of your readers is obliged to go forward with a meeting. Make the introduction and allow them to determine how to proceed. Don’t offer to make arrangements for a meeting unless you’re already sure that both parties are on board and comfortable with your playing this role.

Dear Louise, dear Su,

It’s my pleasure to introduce you two. Louise, Su is the UCLA graduate I mentioned who is hoping to learn more about the analytics field—thank you for agreeing to speak with him. Su, Louise has been working for Simons for nearly twenty years and can give you the best possible guidance on the field.

I think you’ll enjoy knowing each other.

All the best,

Jill

Recommendations

Written recommendations are requested in a lot of situations: for college or graduate school, for other kinds of educational programs, for scholarships, and sometimes for employment purposes.

Think carefully if you’re asked to provide a recommendation. Writing a letter of recommendation is a serious responsibility. You should never agree to write a letter of recommendation for someone who’s unqualified, someone you don’t really know, or someone you feel uncomfortable about supporting for any reason. It’s better for you and the candidate if you say no than if you send out a lukewarm or vague recommendation. In addition, composing a good recommendation requires a significant investment of time and energy, so be sure you’re ready for the task, and give yourself plenty of time to go through several drafts.

UNDERSTAND YOUR PURPOSE AND YOUR READER

It’s easy to slip into generalities and platitudes when you’re writing a recommendation. The cure for this risk is keeping a close eye on your purpose and your reader. Find out as much as you can about the opportunity the candidate is applying for, and focus your efforts on describing the fitness of the candidate for that role.

Put yourself in your reader’s position. What will she be expecting to hear from you? What will she hope to hear? What information can you supply that will make her want to accept the applicant? What can you say to make her understand what’s special about the candidate?

START STRONG AND SPECIFIC

The opening of your recommendation is important. You should announce at the very beginning of your letter who you’re writing for, and for what purpose. Explain how you know the candidate and how long you’ve known him. State explicitly that you recommend the candidate.

Your first paragraph should express how strong your support for the candidate is. If you recommend him for the role, say so. If you offer your strongest possible support for the candidate, say that. If you cannot think of anyone better suited for the position, go ahead and state that here. Be honest about your degree of support, and don’t make the reader persevere all the way to the end of the letter to learn how strongly you feel about the candidate.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

As you think about your content, confirm that you have complete information. Be sure that you understand the opportunity the candidate is applying for. If you feel fuzzy about it, find a website that can fill in the gaps in your understanding. It’s also important that you understand what the candidate hopes to accomplish in the new program, initiative, or position. If you have questions about this, follow up with the candidate and get more details about his plans and aspirations. Get a copy of his résumé, so that your comments will be consistent with the information there.

What’s really valuable about your recommendation are your personal and professional insights into the candidate and his abilities. Your letter can testify for the candidate in a way that his résumé or class transcript cannot. What you know about the candidate, and how that information fits into the bigger picture of the opportunity, is the core of your content.

Think about the special things you can tell the reader about the candidate that the rest of his record may not demonstrate. Think about what the new environment will demand of the candidate, and provide details that indicate he’ll do well in that setting. Be specific and analytical about his qualities and accomplishments; don’t rely on vague praise.

You may have been asked some specific questions in the request for a recommendation—for instance, as part of an application packet. Make sure your letter addresses those questions directly. If you’ve been asked about the candidate’s weaknesses, don’t ignore them. If you’re grappling with a question about the candidate’s shortcomings, write about a weakness that can be overcome. Better yet, describe how the candidate is already overcoming it. Consider whether the opportunity the candidate is applying for might be the perfect setting for him to address an area of weakness, and how he might perform.

FIX IT BEFORE YOU SEND IT

It’s very likely that your first draft will be too long, and it may be unfocused. That’s to be expected. Go ahead and write everything out, then take a break from it if you can. You might have received instructions about the desired length of the letter; don’t go beyond that length, and even if there is no length restriction, don’t exceed two pages. Keeping the length under control will force you to write a tighter and more persuasive letter.

As you revise your draft, imagine how your reader might respond to what you’ve written. Try to sharpen and condense the message. Before you send off the recommendation, proofread it carefully to ensure that you’ve left no typos or other errors that might undermine your credibility.

Below is a sample letter, annotated to highlight key components.

To the Hiring Manager:

It is my great pleasure to recommend Susan McCord for employment. I supervised Susan in her job of database manager at Gibbons International for six years.¶ We are all very sorry that Susan has decided to leave Chicago, but I am very pleased to offer my strongest possible recommendation for her in her new home.#

Susan headed a team that provided data for seven diverse groups of our organization, and she always carried out her work with diligence and aplomb. The data division received many requests for data, often sliced into unusual configurations. It’s part of marketers’ jobs to look for unusual and potentially fruitful patterns in data, and Susan’s familiarity with our data and our software made these creative searches very successful. Many requests came in at the last minute, and Susan was ever unflappable, meeting one insane deadline after another.**

In spite of her very high-stress and high-stakes position, Susan carried out her responsibilities with an almost superhuman goodwill. She was always a pleasure to be around and happy to do whatever it took to get the job done.

I should also mention that Susan was an exemplary role model and guide for the staff who reported to her. Many of her staff were recent graduates getting their first taste of a “real” job. Susan was brilliant at shepherding these entry-level employees, coaching them through stressful periods, and helping them grow into responsible and productive professionals. Susan’s entire team was always ready to accept any challenge with diligence and good humor.††

In closing, it is my pleasure to offer Susan my very strongest recommendation.‡‡ If I can give you any further information, please do not hesitate to contact me at rstraker@gibbonintl.com.

Sincerely,

Rob Straker

LINKEDIN RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommendations on LinkedIn can provide valuable insights about an individual or a business, and recruiters and hiring managers do look at them. While those recommendations may not make or break an application, they can help. To make the recommendation you write as useful as possible, follow these guidelines:

Provide a brief summary of how you know the candidate.

Provide a brief summary of how you know the candidate.

Offer specifics about the candidate’s performance, using measurable results wherever possible. Vague comments like “performed well” and “was a pleasure to work with” can do more harm than good, by suggesting that you don’t really know the candidate well or even that your recommendation is fake.

Offer specifics about the candidate’s performance, using measurable results wherever possible. Vague comments like “performed well” and “was a pleasure to work with” can do more harm than good, by suggesting that you don’t really know the candidate well or even that your recommendation is fake.

Focus on transferable skills, since you don’t know what positions the candidate might be applying for.

Focus on transferable skills, since you don’t know what positions the candidate might be applying for.

Provide examples of the candidate’s performance. Tell a story.

Provide examples of the candidate’s performance. Tell a story.

If you’re writing a recommendation for a business owner, focus on how their business stands out from the competition, why you chose to work with them, and how you feel about the outcome.

If you’re writing a recommendation for a business owner, focus on how their business stands out from the competition, why you chose to work with them, and how you feel about the outcome.

Limit the recommendation to 60–100 words.

Limit the recommendation to 60–100 words.

Thank-yous

Writing a thank-you note appears to be a dying art, particularly in business. The good news is that if you master the art of the thank-you, and practice it regularly, you’ll stand out in the crowd of your ungrateful and thoughtless peers.

When should you write a thank-you message in business? There are some circumstances where a thank-you is absolutely required: when someone has written you a recommendation, when you’ve had a job interview or an informational interview, or when someone’s made an introduction that benefited you. There are other situations where a written thank-you is simply gracious: when someone took on some of your work and helped you get across the finish line, when someone gave you some good advice, or when someone helped you overcome an obstacle you couldn’t have handled on your own. It’s rarely wrong to send a thank-you note, so if you have the impulse, do it.

If you need a reason to send a thank-you beyond simple politeness and gratitude, it’s worthwhile to consider that sending a thank-you note can help strengthen your relationship with your reader. A sincere thank-you can leave a lasting impression.

Here are some hints and tips for sending a thank-you message in a business context:

Keep it appropriate. Your relationship with your reader will help shape the way you write your thank-you. A thank-you to your boss will likely sound different from a thank-you to a peer or someone who reports to you.

Keep it appropriate. Your relationship with your reader will help shape the way you write your thank-you. A thank-you to your boss will likely sound different from a thank-you to a peer or someone who reports to you.

Send your thank-you message promptly.

Send your thank-you message promptly.

Write in your own voice. Sometimes people get nervous when they write thank-you notes, thinking they need to sound more formal or flowery than they usually do. There’s no need to dress up your style. Speak from the heart, and write in your usual businesslike manner.

Write in your own voice. Sometimes people get nervous when they write thank-you notes, thinking they need to sound more formal or flowery than they usually do. There’s no need to dress up your style. Speak from the heart, and write in your usual businesslike manner.

Be specific about what the action or gesture meant to you. A thank-you for an interview should follow a particular form (see here), but a thank-you for help or advice can be more free-flowing. Let your reader know what you’re grateful for: how much time and misery they saved you, for example, or how they set you on the right course.

Be specific about what the action or gesture meant to you. A thank-you for an interview should follow a particular form (see here), but a thank-you for help or advice can be more free-flowing. Let your reader know what you’re grateful for: how much time and misery they saved you, for example, or how they set you on the right course.

If appropriate, specifically acknowledge the effort the reader made in your behalf. For instance, if someone spent a lot of time with you or worked through lunch to help you out, be sure to mention it.

If appropriate, specifically acknowledge the effort the reader made in your behalf. For instance, if someone spent a lot of time with you or worked through lunch to help you out, be sure to mention it.

For Deeper Connection and Reflection, Write It by Hand

Dominique Schurman

From the very early days of humankind, people have had a deep and profound desire to connect with others through words and symbols. As humans, we have discovered that spoken words, often in one ear and out the other, are not always as lasting or impactful as the written word.

We have seen throughout time that the power and impact of the written word has left lasting legacies in families, in relationships, and in history. From the simple note exchanged between friends, to a personally penned letter from the outgoing president to the new, letters have lasted in our lives, adding value and meaning and, at times, changing the course of our lives.

In this age of e-mail and texts, with phones connected to us twenty-four/seven, is there still room for handwriting in business? I think there is.

First, I believe that the lasting, enduring nature of a penned note, coupled with the personal touch of a handwritten expression, has more meaning than an e-mail or a phone call. Both e-mails and phone calls are fleeting, to be either forgotten or deleted, but the impact, emotion, and essence of a handwritten note or letter will last for days, weeks, months, and years. Frank Blake, the former CEO of Home Depot, spent half a day or more each weekend writing personal notes to company employees. “Our people did amazingly generous things for others,” he explained. “It was a great way to end the week.” Blake recognized the personal connection forged by the written word. “In an age of email and texts, there is something personal and special about a handwritten note. I have saved every meaningful note I have ever received.”§§

Second, writing by hand can help you reflect in a deep way. In the safe haven of quiet, with only a pen and our thoughts, we sometimes find the courage and the inspiration to reflect in a unique way and, in so doing, perhaps reach a part of ourselves that we otherwise would not have. A recent article in Harvard Business Review argues that keeping a journal is an important step in becoming an outstanding leader, and that writing in a physical journal will lead to deeper insights: “writing online doesn’t provide the same benefits as writing by hand.”¶¶

Writing in a journal can offer a means to work through difficult issues and challenging times. The time and space involved in this process enables people to absorb issues, to think them through, and to process them in their own way and in their own time, without the need for an immediate response or reaction. This time to reflect can be tremendously important when stressful matters are at hand.

So even—and, actually, especially—today, in our age of technology and instant everything, the magnitude and importance of the handwritten word plays an ever more important part. Reaching out to another with words on paper may leave a lasting impression that even you may not realize in the moment.

Remember the power of the written word, and write many of them. They will enrich your soul and will inspire those around you in ways that you may never know, leaving a footprint of your life and thoughts.

Dominique Schurman is CEO of Schurman Retail Group, whose brands include Papyrus, Marcel Schurman, Paper Destiny, Niquea.D, Carlton Cards, and Clintons.

Apologies

When you do something regrettable at work, a written apology can go a long way toward making things right. Having the good manners and the courage to say “I’m sorry” shows that you value your relationships at work and that you take responsibility for your actions, and it can create goodwill and strengthen relationships for the future. Apologizing to a customer you’ve wronged can help you save business you might otherwise have lost.

Before you start writing, though, consider whether a written apology is the best course. Sometimes an in-person apology means more—partly because it takes more courage, partly because meeting face-to-face can strengthen the relationship.

However you choose to apologize, do it as soon as possible after the offending action. Delaying your apology can allow bad feelings to fester and make the situation worse.

YOUR OBJECTIVE

An apology is easier to write if you focus on what you’re trying to accomplish. Analyzing your objective might sound silly, but it’s easy to stray off message with an apology, especially if you’re feeling defensive. Your main purpose is to acknowledge your mistake and tell your reader you’re sorry for the distress it caused them. Other possible objectives might be to let your reader know how you’re going to fix the problem, if possible, and to assure them that it won’t happen again.

CONSIDER YOUR READER

Think a bit about your reader and how he might respond to your apology. What is your relationship? Is your reader your boss, your customer, someone who reports to you? What effect did your action have on him? Is he mad, hurt, insulted? How do you think he’ll react to your apology? Considering these questions can help you craft a thoughtful and sincere apology.

SAY YOU’RE SORRY RIGHT UP FRONT

Your message should begin with “I’m sorry.” A straightforward expression of regret right at the start lets your reader know you’re sincere. Any explanation should come later.

WHAT ELSE DO YOU WANT TO SAY?

It’s often helpful for the reader to understand the reason behind your action. Note that a reason is not an excuse. Don’t say anything to suggest that what you did was no big deal, and don’t try to shift the blame to anyone else, including the reader. An apology that says “I’m sorry, but . . .” doesn’t sound sincere. If you’re going to apologize, take full responsibility.

You might also let your reader know what you’re doing to fix the problem, if that’s appropriate, and what you’re doing to make sure it never happens again.

Be careful not to say anything in your apology that could create legal liability. If you’re apologizing for poor service or a defective product, check with your company’s legal department for guidance. If you’re apologizing for your own behavior, think about whether legal action over the incident could be possible, and get some advice before you write.

IF SOMETHING FEELS WRONG, FIX IT

Apologies can be tricky, because emotions are often involved. It can be helpful to go through a couple of drafts before you send out your apology. Take a break after you finish your first draft. As you read over it later, think about how your reader might respond. Is the tone sincere? Does the apology really take responsibility for what happened? Will the reader believe that the same kind of thing won’t happen again?

Dear Team:

I’m very sorry for missing the deadline yesterday. I know it’s put us behind and created more work for Andrea and Cian.

As most of you know, I had deadlines for both TYPE and CCS yesterday. I simply couldn’t finish both. I shouldn’t have structured my workload that way—I should have known I wouldn’t be able to deliver on both.

Again, I’m sorry. I promise to pace my work more sensibly in the future and not to leave you cleaning up my mess.

Best,

Una

PROMOTING YOUR BUSINESS AND YOURSELF

Web Copy

Your company’s website is its public face and voice and one of its most powerful tools for sales, marketing, and public relations. Site visitors aren’t always aware when they’re reading good copy, but they recognize bad copy right away. It’s well worth the investment of time and energy to make sure your web copy represents your brand in the best possible way.

NEVER LOSE SIGHT OF YOUR PURPOSE

No matter what kind of business you have, your website is promoting your company, its products and services, its people, and its reputation. Even if you’re not explicitly selling on the site, remember that everything on there creates an impression, and put your best foot forward.

UNDERSTAND YOUR READERS

Of course, you won’t know exactly who’s visiting your website, but it’s worthwhile making the effort to understand the types of readers who will be reading your web copy. Who is your target customer or client?

Marketers often create “personas” of their target customers. A persona is a composite portrait of an individual with the characteristics—including sex, age, race, income, education level, family relationships, goals, desires, and other qualities—of the type of person who might be interested in your product or service. Marketers will typically create several personas to represent the target customers of a product or service. When you come up with your own range of personas, give them names.

Once you’ve constructed a persona, you can use what you know about that individual to write web copy that will appeal to them by addressing their needs, concerns, and interests. What will they be looking for when they visit your site? What will they expect to find? What questions will they have? Your site must address your readers’ needs and expectations. As you build the different sections of your site, keep these questions at the front of your mind.

PUT THE IMPORTANT STUFF UP FRONT

The beginnings of web pages are especially important. Research has shown that web users typically read no more than 20 percent of the copy on any given page.##

Take a minute to think about how you interact with web pages. Chances are that when you’re shopping for a product or service, you’ll visit several sites during your search. If you don’t see what you’re looking for at the top of a page, you’ll probably give up and move on to the next option. So when you’re writing copy for your own site, your most important content should go “above the fold”—that is, in the area of the design at the top of the page.

THINK VISUALLY

Think visually when you’re writing your web copy, and remember that less is often more. The eye tends to “bounce” off big blocks of text. So to help ensure that your copy will be read, use short sentences, chunk them into short paragraphs, and consider using bullet points to make the content easier to scan. Your copy should accommodate plenty of open space on the page. The copy should work harmoniously with the other graphic elements to create a pleasant user experience.

GET YOUR CONTENT RIGHT

People tend to include too much information on websites, especially people creating sites for small businesses. It’s tempting to describe all the features and benefits of your product or service in great detail, but that might be too much for your reader. Your litmus test for content should be “Does it matter to my customer?” That’s the content you want to include. Resist the temptation to add more content, even if it’s something you’re proud of or excited about personally. Don’t drown your visitors in excess copy on the page. Every section of your website should be organized around how you can help your customers.

Consider including a call to action on some or all of your pages, encouraging site visitors to contact you or place an order and making it easy for them to do so.

While we’re talking about content, we also need to explore how you can use copy to drive visitors to your site. The web is evolving quickly, and you should stay up-to-date on the latest ways search engines locate the terms people search for and direct users to sites. Learn about key words and SEO (search engine optimization). If you’re building a site on WordPress or a similar platform, there might be built-in tools you can use to make your site more attractive to searchers; learn about those and take full advantage of them.

ASK TESTERS TO REVIEW YOUR COPY BEFORE YOU FINALIZE IT

In most circumstances, it’s pretty easy to change web copy once it’s live, so it’s not the end of the world if you go live with content that isn’t perfect. But web copy is the kind of thing you tend to forget about—and, honestly, you want to be able to forget about it. You want to be confident in the copy you have on your site so you can move on to more important things. So be sure to review the copy once it’s on the site, to give yourself a better idea of the experience your users will have.

It’s also a good idea to ask a few colleagues or friends to review the site; then you can use their feedback to make improvements. Make sure you let them know specifically what you want feedback on. If you’re looking for their reactions to the copy, tell them that. If you vaguely ask them, “What do you think?,” you’re likely to get random feedback on fonts, colors, images, and so forth. Direct their attention so they can be as helpful as possible.

Blogs

Whether you’re running a small business or working for a big one, your business blog can help you maintain contact with current customers and attract new ones. Regular blogging can increase traffic to your web site, and integrating your blog with social media can help you build an online community around your business and your area of expertise.

YOUR PURPOSE IS TO SERVE YOUR AUDIENCE

It’s important to pinpoint a purpose for your blog. The risk of not doing so is that your content will be unfocused and you’ll end up writing too much that provides too little of value to your readers. Understanding your readers is key to defining your purpose. Here’s a useful sentence to fill in as you think about the purpose of your blog: “My blog serves my readers by _________________.” The answer might be “supplying cutting-edge information about my field” or “providing tools and techniques clients can use.” If you keep the focus on serving customers or readers, you’re less likely to blather on about topics that are interesting to you but not to your customers.

Having a blog gives you the chance to show off your expertise. Make sure your content is valuable to your readers. People will read your blog as long as they find the content valuable. If they don’t, they will move on.

One way to keep readers engaged is to provide variety. It can be hard to find solid subject matter if you’re blogging every week. Keep your core focus, but consider writing some posts about complementary topics, for a change of pace. If you’re a real estate agent, you can offer tips on renovation or landscaping. If you’re a chiropractor, you can discuss nutrition. Consider inviting guest bloggers who are experts in adjacent fields to contribute a blog post now and then (and ask if you can reciprocate, thereby introducing your business and your expertise to their readers).

THE HOOK MATTERS

Think about the last time you read a blog post. Did you read through to the end? Chances are good that you didn’t, unless it was a particularly interesting article. Attention spans are short, so you need to ensure that your post starts with an engaging hook that grabs your readers’ interest. Once you have your readers’ attention, motivate them to read on by front-loading your most important content. Don’t save your most critical points for last, or your readers might miss them.

BE CONCISE

Readers sometimes give up on blog posts because there’s too much content or there’s too much low-quality content. Experts differ on how long the ideal blog post should be, and recommendations about length have changed over time. It’s worthwhile doing some research on what works best in terms of length, but it’s always a good practice to go through your early drafts and cut out anything that seems superfluous or less engaging than the rest of the content. Your blog post should be long enough to offer useful insights to your readers, but it shouldn’t go on longer than it needs to.

MAINTAINING YOUR BLOG

Blog regularly. You don’t have to blog every week—that can be a hard pace to maintain—but do pick a regular interval and stick to it. Readers will get discouraged if they come back to your blog and find nothing new.

Share your blog posts on social media. Promoting your blog posts on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn can draw new audiences. You might also want to include a sign-up form on your website so you can e-mail your list, announcing when a new blog post is up.

Consider whether you want to allow comments on your blog. This can be a good way to engage with readers, make connections, and provide even more content to your followers by answering questions. It also means that you’ll need to monitor the comments regularly, to get rid of spam posts and moderate any arguments that might flare up. You’ll need to assess whether you have the time and if it’s worth your energy.

Once you’ve launched your blog, don’t abandon it. A blog with only a few old posts looks dismal. If you find that you can’t maintain a regular blog, think about hiding it or archiving the old posts. You can always reactivate the page if you decide to start blogging again.

Social Media

Various forms of social media offer businesses of all sizes the opportunity to connect with customers and potential customers in an entertaining and enriching way. Learning to use social media gives you the chance to provide value to customers between transactions and can help ensure that your customers don’t forget you.

Creating Content for Your Website or Blog

Rieva Lesonsky

Content marketing is currently being buzzed about—and for good reason. It’s a fast-growing and proven component of marketing plans for small businesses. But since most small business owners didn’t major in English or journalism, they can find creating content challenging.

First, it’s important to know what makes content effective. Your three top goals should be:

1.Your content needs to be relevant to your market.

2.It should be designed to elicit a response from readers.

3.It should be engaging and interesting.

Next, you need to create a content marketing plan. Components of that plan include:

Defining your goals. Do you want to get leads? Increase brand awareness? Establish your expertise? Educate your market? Drive traffic to your site or store? Inspire your audience?

Defining your goals. Do you want to get leads? Increase brand awareness? Establish your expertise? Educate your market? Drive traffic to your site or store? Inspire your audience?

Understanding your audience. What do they want or need to know? To buy? What types of content do they want?

Understanding your audience. What do they want or need to know? To buy? What types of content do they want?

Picking a voice that will be consistent across your brand. That voice needs to be authentic—and targeted to your potential and current customers and clients.

Picking a voice that will be consistent across your brand. That voice needs to be authentic—and targeted to your potential and current customers and clients.

Establishing some parameters: How often will you post? What’s your budget? Who’s responsible for the various tasks?

Establishing some parameters: How often will you post? What’s your budget? Who’s responsible for the various tasks?

If your site already has content on it, it’s important to review, revise, and update it periodically. Many experts recommend that you add new content to your site at least twice a week. Don’t panic; here are some ideas about how you can generate content and still have time to run your business:

Feature a customer of the week or month. Create a template of five to ten questions and e-mail the list to your customers. Make sure you edit the respondents’ grammar before you post their comments.

Feature a customer of the week or month. Create a template of five to ten questions and e-mail the list to your customers. Make sure you edit the respondents’ grammar before you post their comments.

Post lists, checklists, or tips. These shouldn’t be too long; people don’t have time to read through dozens of tips.

Post lists, checklists, or tips. These shouldn’t be too long; people don’t have time to read through dozens of tips.

Advertise special offers or promotions.

Advertise special offers or promotions.

Turn your FAQs into blog posts.

Turn your FAQs into blog posts.

Use guest bloggers.

Use guest bloggers.

Publish product reviews.

Publish product reviews.

Hire freelancers—if you have the budget.

Hire freelancers—if you have the budget.

Repurpose content: turn blogs into white papers, e-books, podcasts, and videos.

Repurpose content: turn blogs into white papers, e-books, podcasts, and videos.

Run e-mail interviews with relevant people in your industry.

Run e-mail interviews with relevant people in your industry.

Educate customers with “how-to” articles.

Educate customers with “how-to” articles.

Draw on your business’s expertise—for example, if you own a food-related business, spotlight recipes.

Draw on your business’s expertise—for example, if you own a food-related business, spotlight recipes.

Two final tips:

1.Use photos, charts, and graphics. Blogs, articles, and social media posts with images get far more views than text-only posts.

2.Don’t forget to include a call to action. People need to be told what you want them to do.

And finally, if you’re wondering if all this is worth it—the answer is yes. According to TechClient.com, websites with a blog have 434 percent more indexed pages.*** That means higher rankings in the search engines.

Rieva Lesonsky is a cofounder and the CEO of GrowBiz Media, a custom content-creation company focusing on small businesses and entrepreneurship, and a co-owner of the blog SmallBizDaily.

CHOOSE THE RIGHT PLATFORM(S) FOR YOUR BRAND